Abstract

A previous phylogenetic study suggested that mammalian gammaretroviruses may have originated in bats. Here we report the discovery of RNA transcripts from two putative endogenous gammaretroviruses in frugivorous (Rousettus leschenaultii retrovirus, RlRV) and insectivorous (Megaderma lyra retrovirus, MlRV) bat species. Both genomes possess a large deletion in pol, indicating that they are defective retroviruses. Phylogenetic analysis places RlRV and MlRV within the diversity of mammalian gammaretroviruses, with the former falling closer to porcine endogenous retroviruses and the latter to Mus dunni endogenous virus, koala retrovirus and gibbon ape leukemia virus. Additional genomic mining suggests that both microbat (Myotis lucifugus) and megabat (Pteropus vampyrus) genomes harbour many copies of endogenous retroviral forms related to RlRV and MlRV. Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis reveals the presence of three genetically diverse groups of endogenous gammaretroviruses in bat genomes, with M. lucifugus possessing members of all three groups. Taken together, this study indicates that bats harbour distinct gammaretroviruses and may have played an important role as reservoir hosts during the diversification of mammalian gammaretroviruses.

Introduction

Retroviruses (family Retroviridae) are a large and diverse family of positive-sense enveloped RNA viruses with a genomic RNA molecule of 7–12 kb in length (Coffin et al., 1997). All retroviruses contain three major proteins: Gag, which directs the synthesis of internal virion proteins; Pol, which comprises the protease, reverse transcriptase and integrase enzymes; and Env, which constitutes the viral envelope. The hallmark of retroviruses is their unique replication strategy, which involves reverse transcription of the virion RNA into dsDNA and the subsequent integration into the host genome (Coffin et al., 1997). Infection of germline cells can lead to the vertical transmission of retroviruses from parent to offspring in the form of Mendelian alleles. Such integrated proviruses are known as endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) (Gifford & Tristem, 2003; Weiss, 2006) and can occur in either expressed or silent forms, and as complete or partial (defective) genomes. ERVs can influence host evolution, either via genomic rearrangements (Hughes & Coffin, 2001) or through the regulation of gene expression (Sverdlov, 2000; Jern & Coffin, 2008).

Retroviruses have both complex and simple genome organizations (e.g. lentiviruses and gammaretroviruses, respectively) and are classified into two subfamilies. The subfamily Orthoretrovirinae comprises the genera Alpharetrovirus, Betaretrovirus, Deltaretrovirus, Epsilonretrovirus, Gammaretrovirus and Lentivirus, and the subfamily Spumaretrovirinae contains the single genus Spumavirus. Retroviruses have been discovered in a wide variety of vertebrate species including mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians, and cause lymphoma, leukaemia and immunodeficiency in some species (Coffin et al., 1997; Voisset et al., 2008).

Bats are the second largest group of mammals, with ~1100 documented species and they harbour more than 60 distinct emerging and re-emerging human viral pathogens, including representatives from the families Rhabdoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Coronaviridae, Togaviridae, Flaviviridae, Bunyaviridae, Reoviridae, Arenaviridae, Herpesviridae, Picornaviridae and Filoviridae (Calisher et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2007). Our previous analysis of the bat transcriptome established that seven of 11 bat species (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, R. pusillus, R. pearsoni, R. megaphyllus, R. affinis, Myotis ricketti and Pteropus alecto) harbour gammaretroviruses and exhibit a phylogenetic pattern consistent with the notion that extant mammalian gammaretroviruses originated in bats (Cui et al., 2012). In the current study, amplification of retroviral sequences from brain RNA of Rousettus leschenaultii (a frugivorous megabat) and Megaderma lyra (an insectivorous microbat) revealed the presence of gammaretroviral sequences in each species that were distinct from those identified previously, suggesting that bats harbour a diverse range of gammaretroviruses. To achieve a broader-scale evolutionary analysis we employed genomic mining of the publicly available bat genomes of Myotis lucifugus and Pteropus vampyrus and performed a phylogenetic analysis of newly identified endogenous gammaretroviral sequences.

Results

Defective bat gammaretroviruses

We successfully cloned bat gammaretroviral cDNAs from R. leschenaultii (R. leschenaultii retrovirus, denoted RlRV, 3041 bp) and M. lyra (denoted MlRV, 2876 bp) brain tissue. Nucleotide blastn analysis (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) revealed that RlRV exhibited 70 % nucleotide sequence similarity to porcine ERV type C (PERV-C, GenBank accession no. EF133960, e-value = 0.0), while MlRV exhibited 72 % similarity to Mus dunni endogenous virus (MDEV, AF053745, e-value = 0.0). Both genomes were defective due to large deletion mutations in pol (Fig. S1, available in JGV Online). Specifically, RlRV harboured a 1602 bp deletion in pol corresponding to the reverse-transcriptase-coding region, while MlRV contained a 732 bp deletion in pol corresponding to the 3′ and 5′ coding regions of protease and reverse transcriptase, respectively. While both RlRV and MlRV contained pol deletions, they were in different genomic positions, suggesting that they occurred independently.

Phylogenetic analyses of bat gammaretroviruses

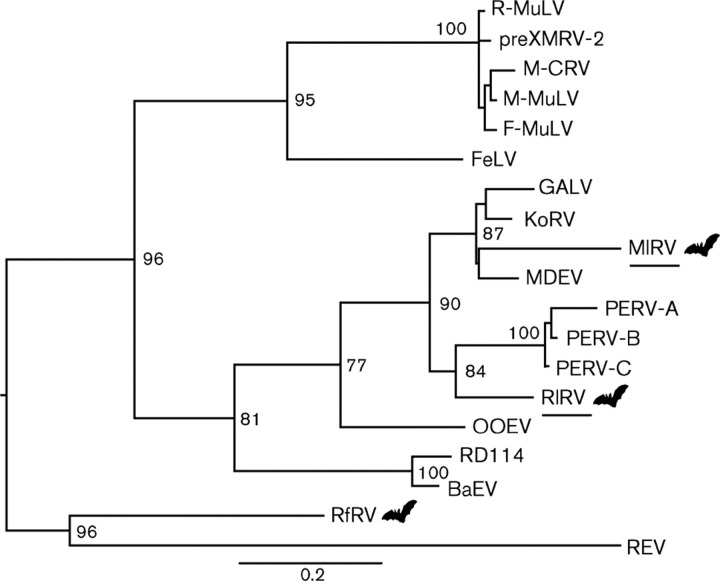

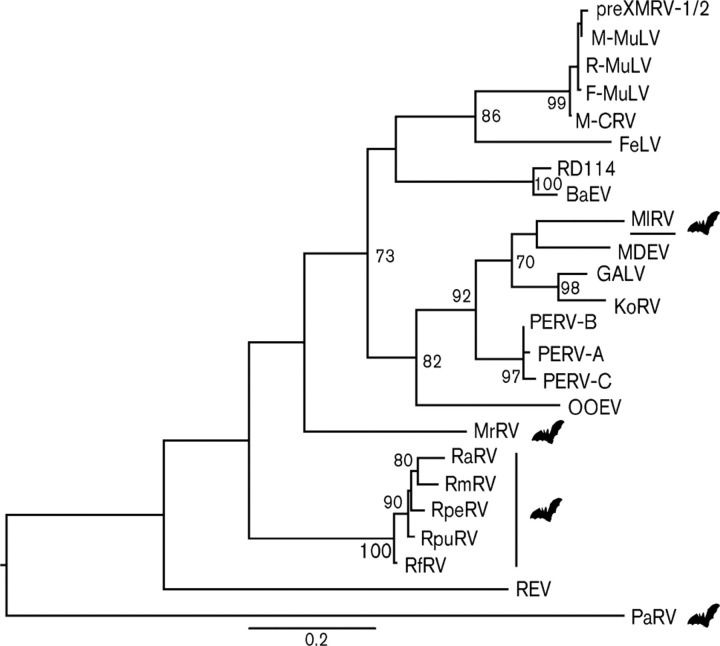

Gag amino acid sequences from both RlRV and MlRV and extant gammaretroviruses were used to perform a phylogenetic analysis. This revealed that RlRV and MlRV fell into different phylogenetic positions (Fig. 1). Specifically, MlRV formed a well-supported (bootstrap = 87 %) monophylogenetic group with MDEV, koala retrovirus (KoRV) and gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV), while RlRV clustered outside of the three porcine retroviruses (bootstrap = 84 %). Pol amino acid sequences from MlRV and extant gammaretroviruses were similarly used to infer a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2), in which MlRV exhibited the same phylogenetic position as in the Gag analysis (bootstrap = 70 %). However, it was not possible to perform a phylogenetic analysis of RlRV using Pol due to the large deletion in this gene. The seven other previously reported bat retroviruses (RfRV, RpuRV, RpeRV, RmRV, RaRV, MrRV and PaRV) were positioned at the base of both phylogenies, as in an earlier study (Cui et al., 2012). Based on these data, MlRV, RlRV and RfRV probably represent different retroviruses.

Fig. 1.

ML tree of the Gag gene (amino acids) of gammaretroviruses. The viral sequences detected in this study are underlined. RlRV was isolated from R. leschenaultii, MlRV was isolated from M. lyra and RfRV was taken from R. ferrumequinum. Bat icons are shown to indicate bat gammaretroviruses. Bar, 0.2 amino acid substitutions per site and the tree is midpoint rooted for clarity only. Only bootstrap values >70 % are shown. GenBank nos are shown in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

ML tree of the Pol gene (amino acids) of gammaretroviruses. The viral sequence underlined was detected in this study. RfRV, RpuRV, RpeRV, RmRV, RaRV, MrRV and PaRV represent gammaretroviruses isolated from R. ferrumequinum, R. pusillus, R. pearsoni, R. megaphyllus, R. affinis, M. ricketti and P. alecto, respectively (Cui et al., 2012). Bat icons are shown to indicate bat gammaretroviruses. Bar, 0.2 amino acid substitutions per site and the tree is midpoint rooted for clarity only. Only bootstrap values >70 % are shown. GenBank nos are shown in Table 3.

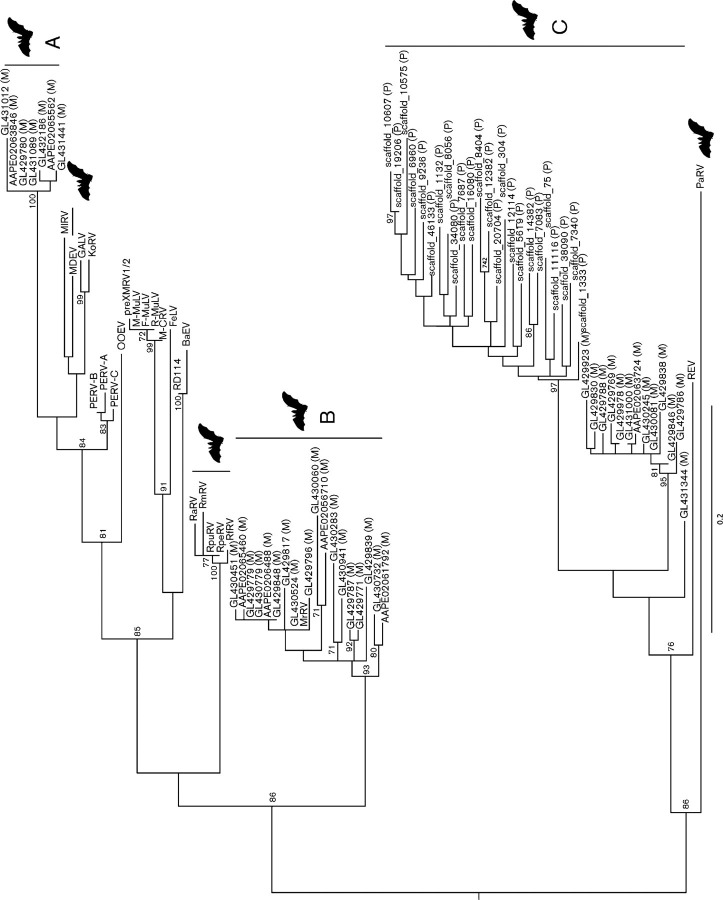

Endogenous gammaretroviruses in bat genomes

To further verify that bats indeed harbour genetically diverse gammaretroviruses (i.e. viruses related to RlRV, MlRV and RfRV), we explored the endogenous gammaretroviruses present in the two bat genomes (M. lucifugus and P. vampyrus) available at the Ensembl Genome Browser (EGB) (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). This analysis revealed that M. lucifugus and P. vampyrus harboured at least 57 and 50 copies of endogenous gammaretroviruses, respectively (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis using Pol amino acid sequences (n = 86, 116 residues in length) supports the notion that bats harbour an extensive genetic diversity of ERVs as those lineages from bats fell into three different major groups (A, B and C; Fig. 3), among which groups A and B were exclusive to M. lucifugus, while group C was found in both bat species. More precisely, group A viruses were embedded within the genetic diversity of extant mammalian gammaretroviruses, while group B viruses, which include MrRV (host M. ricketti), were placed basal to their mammalian counterparts. Finally, the diverse group C viruses were most closely related to the avian reticuloendotheliosis virus and the bat PaRV (host P. alecto) sequences.

Table 1.

Results of the nucleotide blast analysis of the two bat genomes

| Species | Scaffold name | Size (nt) | Similarity (%) genomic blast | e-value | Query | Closest match | GenBank accession no. reciprocal blast | Similarity (%) | e-value |

| AAPE02065460 | 383 | 63.71 | 5.6e−120 | MlRV | PERV | Y17013 | 72 | 3e−37 | |

| GL429796 | 383 | 63.45 | 2.8e−117 | MlRV | RfRV | JQ303225 | 73 | 6e−34 | |

| AAPE02063846 | 233 | 74.25 | 5.4e−106 | MlRV | PERV | HQ540591 | 76 | 2e−37 | |

| GL429978 | 272 | 59.19 | 2.1e−50 | MlRV | F-MuLV | D88386 | 69 | 3e−04 | |

| GL429796 | 193 | 64.25 | 1.3e−45 | MlRV | MuLV | K03363 | 68 | 1e−07 | |

| GL429779 | 99 | 69.70 | 5.5e−24 | MlRV | MuLV | AY818896 | 79 | 1e−08 | |

| AAPE02066375 | 140 | 75.00 | 1.4e−60 | AAPE02063846 | PERV | AF356697 | 76 | 9e−20 | |

| AAPE02065562 | 726 | 95.87 | 0.0 | AAPE02063846 | PERV | HQ540595 | 68 | 6e−63 | |

| GL429966 | 131 | 63.36 | 6.4e−30 | AAPE02063846 | PERV | HQ540595 | 70 | 1e−04 | |

| GL429780 | 1226 | 98.78 | 0.0 | AAPE02063846 | PERV | HQ540595 | 69 | 2e−129 | |

| GL431089 | 1226 | 98.21 | 0.0 | AAPE02063846 | PERV | GU980187 | 69 | 1e−124 | |

| GL431012 | 1226 | 96.00 | 0.0 | AAPE02063846 | PERV | HQ540595 | 67 | 1e−94 | |

| GL432186 | 1226 | 94.70 | 0.0 | AAPE02063846 | PERV | HQ540595 | 70 | 1e−124 | |

| GL431441 | 1226 | 93.64 | 0.0 | AAPE02063846 | PERV | HQ540595 | 69 | 3e−120 | |

| AAPE02056710 | 803 | 85.80 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | MuLV | Y13893 | 67 | 2e−51 | |

| GL429855 | 1090 | 99.54 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PreXMRV-1 | FR871849 | 66 | 9e−63 | |

| GL429771 | 833 | 84.27 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | M-MuLV | AF462057 | 68 | 3e−48 | |

| GL430779 | 1226 | 99.67 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PreXMRV-1 | FR871849 | 66 | 5e−73 | |

| AAPE02064844 | 1226 | 99.51 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PreXMRV-1 | FR871849 | 66 | 5e−73 | |

| GL429848 | 1226 | 99.43 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PreXMRV-1 | FR871849 | 66 | 1e−73 | |

| GL430451 | 1226 | 99.35 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PreXMRV-1 | FR871849 | 66 | 3e−69 | |

| GL430524 | 1227 | 97.64 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PreXMRV-1 | FR871849 | 66 | 9e−70 | |

| GL429817 | 1226 | 94.45 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | BaEV | X05470 | 67 | 1e−48 | |

| AAPE02061792 | 1227 | 89.81 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | R-MuLV | U94692 | 65 | 3e−63 | |

| GL430732 | 1083 | 89.94 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PERV | Y17013 | 82 | 4e−55 | |

| GL429777 | 940 | 98.30 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PreXMRV-1 | FR871849 | 67 | 6e−58 | |

| AAPE02072435 | 831 | 99.16 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | M-MuLV | AF033811 | 67 | 1e−52 | |

| GL429839 | 695 | 84.89 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | M-MuLV | AF462057 | 67 | 5e−51 | |

| GL430941 | 510 | 87.06 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | RfRV | JQ303225 | 74 | 3e−33 | |

| GL429774 | 707 | 97.60 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PERV | Y17013 | 73 | 2e−43 | |

| GL429787 | 747 | 84.87 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | MuLV | EU075329 | 66 | 1e−33 | |

| AAPE02070219 | 592 | 90.03 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | MuLV | X57540 | 67 | 2e−36 | |

| GL430283 | 683 | 81.41 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | M-MuLV | AF462057 | 66 | 1e−33 | |

| GL430288 | 422 | 97.63 | 0.0 | AAPE02065460 | PreXMRV-1 | FR871849 | 68 | 3e−32 | |

| GL430554 | 351 | 91.17 | 2.9e−264 | AAPE02065460 | F-MuLV | D88386 | 67 | 3e−18 | |

| GL430058 | 261 | 88.51 | 1.4e−186 | AAPE02065460 | MuLV | Y13893 | 71 | 2e−24 | |

| GL430325 | 207 | 98.55 | 8.6e−173 | AAPE02065460 | PERV | HM159246 | 76 | 1e−19 | |

| AAPE02069675 | 209 | 93.78 | 4.6e−149 | AAPE02065460 | MuLV | X99935 | 79 | 4e−14 | |

| GL430988 | 228 | 82.89 | 2.3e−144 | AAPE02065460 | MuLV | X78945 | 68 | 7e−05 | |

| GL429991 | 99 | 97.98 | 1.8e−77 | AAPE02065460 | M-MuLV | AF462057 | 75 | 4e−03 | |

| GL430537 | 290 | 90.69 | 1.1e−216 | AAPE02065460 | R-MuLV | U94692 | 71 | 1e−22 | |

| GL430060 | 321 | 88.16 | 2.0e−221 | AAPE02065460 | MDEV | AF053745 | 70 | 9e−12 | |

| GL429786 | 822 | 92.82 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | FJ439119 | 66 | 1e−40 | |

| GL429830 | 1082 | 93.90 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 66 | 3e−49 | |

| GL430081 | 1079 | 95.92 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 67 | 2e−57 | |

| GL429788 | 1218 | 93.43 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 66 | 1e−49 | |

| GL429838 | 1218 | 93.60 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 65 | 2e−52 | |

| GL429846 | 1218 | 93.76 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 65 | 5e−60 | |

| AAPE02063724 | 1218 | 94.01 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 65 | 1e−48 | |

| GL431000 | 1218 | 94.01 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 65 | 9e−51 | |

| GL429769 | 1218 | 97.62 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 66 | 1e−49 | |

| GL430245 | 439 | 92.03 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | DQ003591 | 66 | 1e−11 | |

| GL431344 | 1027 | 63.10 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | FJ439120 | 67 | 6e−71 | |

| GL429923 | 1108 | 94.04 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 65 | 1e−28 | |

| GL430254 | 410 | 94.63 | 0.0 | GL429978 | REV | GQ415646 | 68 | 1e−23 | |

| GL431333 | 227 | 88.99 | 8.3e−159 | GL429978 | REV | DQ003591 | 71 | 2e−05 | |

| GL429781 | 331 | 94.86 | 7.1e−262 | GL429978 | RD114 | AB559882 | 71 | 4e−10 | |

| Scaffold_3915 | 137 | 67.88 | 2.2e−38 | MlRV | RfRV | JQ303225 | 79 | 5e−16 | |

| Scaffold_20704 | 85 | 65.88 | 4.1e−18 | MlRV | REV | GQ415646 | 81 | 3e−04 | |

| Scaffold_304 | 248 | 58.06 | 2.1e−41 | RfRV | PERV | EF133960 | 81 | 2e−06 | |

| Scaffold_16942 | 213 | 60.09 | 1.4e−35 | RfRV | PERV | AF356698 | 76 | 5e−06 | |

| Scaffold_72411 | 51 | 90.20 | 1.8e−28 | RfRV | RfRV | JQ303225 | 90 | 3e−11 | |

| Scaffold_16080 | 1221 | 92.96 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | GQ415646 | 79 | 2e−33 | |

| Scaffold_1333 | 1217 | 92.52 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 79 | 3e−38 | |

| Scaffold_7340 | 1229 | 91.62 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | GQ415646 | 65 | 4e−42 | |

| Scaffold_38090 | 1217 | 90.80 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 65 | 6e−34 | |

| Scaffold_7083 | 1218 | 90.72 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | RfRV | JQ303225 | 64 | 2e−21 | |

| Scaffold_11116 | 1217 | 90.39 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | AY842951 | 64 | 3e−32 | |

| Scaffold_12382 | 886 | 91.99 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | RfRV | JQ303225 | 65 | 2e−25 | |

| Scaffold_14223 | 736 | 91.03 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | RfRV | JQ303225 | 68 | 2e−19 | |

| Scaffold_11497 | 670 | 93.43 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 65 | 7e−24 | |

| Scaffold_12114 | 659 | 91.05 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | RfRV | JQ303225 | 68 | 1e−19 | |

| Scaffold_8404 | 462 | 90.91 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | RfRV | JQ303225 | 66 | 1e−19 | |

| Scaffold_4970 | 445 | 91.91 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | RfRV | JQ303225 | 67 | 6e−16 | |

| Scaffold_46133 | 655 | 91.60 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 66 | 6e−24 | |

| Scaffold_7687 | 971 | 91.86 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 65 | 6e−39 | |

| Scaffold_22110 | 919 | 92.27 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | DQ237901 | 65 | 1e−29 | |

| Scaffold_20103 | 919 | 91.73 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | AY842951 | 65 | 7e−32 | |

| Scaffold_10575 | 672 | 91.37 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | DQ237901 | 65 | 4e−20 | |

| Scaffold_75 | 1066 | 93.15 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 66 | 4e−35 | |

| Scaffold_7148 | 1016 | 93.60 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 65 | 1e−28 | |

| Scaffold_9236 | 1205 | 92.86 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 82 | 5e−35 | |

| Scaffold_74973 | 594 | 92.93 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | RfRV | JQ303225 | 66 | 4e−19 | |

| Scaffold_14382 | 1213 | 90.35 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 77 | 1e−22 | |

| Scaffold_12281 | 451 | 90.24 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | RfRV | JQ303225 | 68 | 8e−21 | |

| Scaffold_11711 | 368 | 89.13 | 1.9e−265 | Scaffold_304 | FeLV | M18247 | 66 | 2e−07 | |

| Scaffold_21760 | 863 | 91.31 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | AY842951 | 65 | 3e−30 | |

| Scaffold_19206 | 917 | 92.26 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 65 | 4e−34 | |

| Scaffold_8056 | 925 | 91.03 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 65 | 4e−34 | |

| Scaffold_10607 | 917 | 91.82 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | DQ237901 | 65 | 2e−32 | |

| Scaffold_6960 | 916 | 91.59 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 65 | 7e−32 | |

| Scaffold_268 | 538 | 90.33 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 67 | 1e−18 | |

| Scaffold_34080 | 668 | 91.17 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | AY842951 | 64 | 6e−12 | |

| Scaffold_19143 | 615 | 90.89 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 65 | 1e−13 | |

| Scaffold_1132 | 698 | 92.69 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | GQ415646 | 67 | 4e−33 | |

| Scaffold_12008 | 449 | 92.43 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 67 | 2e−22 | |

| Scaffold_11643 | 348 | 92.24 | 3.1e−263 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 70 | 6e−21 | |

| Scaffold_6441 | 320 | 93.44 | 1.5e−250 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 69 | 1e−16 | |

| Scaffold_508 | 484 | 90.08 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | SNV | DQ237902 | 67 | 4e−18 | |

| Scaffold_5619 | 883 | 91.85 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 67 | 5e−27 | |

| Scaffold_8671 | 638 | 90.13 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 66 | 3e−27 | |

| Scaffold_4506 | 438 | 92.69 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 67 | 9e−20 | |

| Scaffold_7843 | 441 | 92.06 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | REV | FJ439120 | 66 | 6e−16 | |

| Scaffold_16167 | 406 | 91.87 | 5.7e−301 | Scaffold_304 | PERV | EF133960 | 70 | 7e−03 | |

| Scaffold_10142 | 475 | 73.47 | 9.9e−232 | Scaffold_304 | REV | DQ003591 | 65 | 5e−17 | |

| Scaffold_1164 | 608 | 90.79 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | PreXMRV-1 | FR872816 | 68 | 3e−08 | |

| Scaffold_76639 | 544 | 90.99 | 0.0 | Scaffold_304 | PERV | EF133960 | 70 | 2e−04 |

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic diversity of bat gammaretroviruses. The viral sequence detected in this study is underlined. ERVs are shown using scaffold names, with (M) denoting M. lucifugus and (P) P. vampyrus. The three major groups of ERVs are marked A, B and C. Bat icons are shown to indicate bat viruses. Bar, 0.2 amino acid substitutions per site and the tree is midpoint rooted for clarity only. Only bootstrap values >70 % are shown. GenBank nos are shown in Table 3.

Timing of gammaretroviral invasion into bat genomes

ERVs are relatives of extant retroviruses that have been effectively fossilized at their time of insertion into the host germline (Jern & Coffin, 2008). Sixteen (14 of M. lucifugus and two of P. vampyrus) complete retroviral proviral genomes were recovered, flanked by long-terminal repeats (LTRs) (Table 2). All 16 proviral genomes were defective, among which four possessed intact gag, pol and/or env gammaretroviral genes, six lacked env (either deleted or highly fragmented) and two possessed a proviral genome much longer than expected as a consequence of insertions and/or duplications. Although five ORFs (gag, pol and/or env) were classified as defective, they were essentially intact except for minor point mutations that resulted in reading frame shifts or in-frame stop codons; in these instances, sequencing and/or assembly artefacts cannot be entirely excluded. Overall, the sequence similarity among the LTRs of these ERVs ranged from 89.4 to 99.5 %. Using a number of bat nuclear genes and a set of calibration times taken from the fossil record, we estimated the evolutionary rate of genomic DNA for both mega- and microbats, and from this, the dates of retroviral invasion. Accordingly, our estimates of the rates of evolutionary change were 0.8 and 1.9×10−9 nucleotide substitutions per site year−1 for the mega- and microbats, respectively. Applying these substitution rates to the ERV LTRs, we estimated that the bat gammaretroviruses invaded the genomes on timescales ranging from 2.4 to 64.6 million years ago (Mya) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Information on the endogenous gammaretroviruses of bats detected in this study

| Species | Scaffold name | ERV group | Size (nt) | LTR similarity (%) | gag | pol | env |

| AAPE02061792 | B | 8 727 | 98.5 | Intact | Defective* | Intact | |

| AAPE02063846 | A | 8 497 | 99.2 | Intact | Defective* | Defective* | |

| AAPE02065460 | B | 7 454 | 92.1 | Defective | Defective | Absent | |

| AAPE02065562 | A | 8 297 | 99.2 | Defective | Defective | Defective | |

| GL429769 | C | 8 396 | 98.6 | Defective | Defective | Defective | |

| GL429771 | B | 7 884 | 99.5 | Intact | Intact | Absent | |

| GL429779 | B | 7 497 | 99.1 | Defective | Intact | Absent | |

| GL429786 | C | 8 004 | 97.9 | Defective | Defective† | Defective | |

| GL429787 | B | 8 044 | 99.0 | Defective† | Defective | Absent | |

| GL429923 | C | 8 435 | 94.1 | Defective | Defective | Defective | |

| GL430060 | B | 8 467 | 90.7 | Defective | Defective | Defective | |

| GL430524 | B | 7 739 | 98.2 | Defective | Defective | Absent | |

| GL430941 | B | 12 211 | 91.0 | Defective | Defective | Defective | |

| GL431000 | C | 8 419 | 90.8 | Defective | Defective | Defective | |

| Scaffold_12382 | C | 14 402 | 89.4 | Defective | Defective | Absent | |

| Scaffold_16080 | C | 8 427 | 97.0 | Defective | Defective | Defective |

ORF intact except for a few minor in-frame stop codons.

ORF intact except for a stop codon and/or frame shift.

Discussion

There is mounting evidence that bats harbour diverse viruses that may occasionally emerge as important human pathogens (Calisher et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2007), including Ebola viruses (Leroy et al., 2005), SARS coronavirus (Li et al., 2005; Lau et al., 2005), rhabdoviruses (Kuzmin et al., 2006), henipaviruses (Field et al., 2007), reoviruses (Chua et al., 2007), Japanese encephalitis viruses (Cui et al., 2008) and paramyxoviruses (Drexler et al., 2012). How bats are able to carry so many viruses without overt signs of illness is uncertain and has become a major research question. However, several of their biological characteristics, including often massive population densities, species richness, ability to fly, torpor or hibernation and relatively long lifespans are likely to make them ideal viral reservoirs (Calisher et al., 2006).

Our previous study suggested that extant mammalian gammaretroviruses may have originated in bats. Although this theory will clearly need to be verified with a larger sample of viruses from diverse mammalian taxa, it is supported by those phylogenetic analyses undertaken to date and which depict the (known) sample of mammalian gammaretroviruses as nestled within the diversity of viruses sampled from bats (Cui et al., 2012). The analysis undertaken in this paper further supports this notion, in particular showing that bats serve as reservoirs for a range of genetically diverse gammaretroviruses. Specifically, our phylogenetic analysis revealed that MlRV grouped with MDEV, KoRV and GALV, while RlRV clustered with the PERVs. It is also noteworthy that all the bat gammaretroviruses reported in this study and in our previous report (Cui et al., 2012) have one feature in common: they have either major deletions or frameshift mutations in pol, indicating that they are defective. It is clear that the viruses analysed in the current study are defective: the large pol deletion in the RlRV genome will not produce an active reverse transcriptase and the truncation in MlRV would result in the lack of an active protease and reverse transcriptase.

Our genomic mining analysis indicates that the M. lucifugus and P. vampyrus genomes have multiple copies of defective endogenous gammaretroviruses. Interestingly, M. lucifugus harbours three phylogenetically divergent retroviral groups, indicating that multiple germline integration events (with respect to both retroviral type and the time of occurrence) have taken place in this species. Indeed, LTRs of these endogenous gammaretroviruses exhibit genetic divergences in the range 0.5–10 %, which are indicative of the sequential infection of germline cells by gammaretroviruses during long-term evolution; this conclusion is further supported by our molecular dating analysis which reveals an extremely wide range in estimated invasion times. However, it is also noteworthy that two ERV genomes (GenBank accession nos AAPE02061792 and AAPE02063846) seem to contain intact genes, which suggests a recent integration of some gammaretroviruses into bat genomes. More generally, the presence of genetically diverse gammaretroviral elements in the bat genomes (at least in M. lucifugus) demonstrates that bats probably serve as important natural reservoirs for gammaretroviruses.

At present, defective bat gammaretroviruses have been documented in only nine bat species in China and Australia. Due to the species richness and worldwide distribution of bats, future studies involving far wider sampling are required to delineate the genetic diversity of bat gammaretroviruses, as well as global patterns of viral transmission.

Methods

RT-PCR.

The Animal Ethics Committee of East China Normal University approved all the studies undertaken (approval number 20110224). Whole brain tissue of R. leschenaultii and M. lyra (three individuals of each species) was processed immediately post-necropsy and the total RNA was extracted using the SV total RNA isolation system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For the first strand cDNA synthesis, 2.5 µg total RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 20 µl. We employed a previously published PCR procedure to amplify retroviral sequences in bat cDNAs (Cui et al., 2012). However, amplification of the complete genomes was unsuccessful. All PCR products were ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and transformed into Escherichia coli for plasmid amplification and purification. The universal T7 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATGAGG-3′) and SP6 (5′-ATTTAGGTGACACTATAG-3′) sequencing primers were used to sequence all positive molecular clones on an ABI 3730 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The two bat sequences have been deposited in GenBank: RlRV gag, JQ951957; RlRV pol, JQ951958; MlRV gag, JQ951955 and MlRV pol, JQ951956.

Genomic mining.

To identify endogenous bat gammaretroviruses, we employed a previously published protocol (Cui & Holmes, 2012), involving genomic mining of the 7× coverage M. lucifugus (version Myoluc2.0) and 2.63× P. vampyrus (version pteVam1) genomes available in the EGB (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). We used ~1460 bp sequences of MlRV and RfRV pol as queries and employed the search tool blat in EGB. A cut-off e-value of 1e−10 was used to signify a positive match. A second round blat analysis was carried out using the first round positive hits. Next, a reciprocal nucleotide blastn analysis (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) using the endogenous viruses discovered above as the queries was employed to confirm their relationships to their exogenous counterparts. Scaffolds containing complete LTRs flanking putative proviral gammaretrovirus sequences were manually assessed for complete gag, pol and env ORFs using blastp and blastx for translated and nucleotide sequences, respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis.

To determine the evolutionary relationships among the different gammaretroviruses, phylogenetic trees were inferred using amino acid sequences. We retrieved reference sequences (Table 3) of two major proteins (Gag and Pol) from GenBank. All Gag and Pol protein sequences were aligned in clustal_x (Larkin et al., 2007) and checked manually in Se-Al(http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/seal/). We also used the Gblocks program to eliminate regions of high sequence diversity and hence uncertain alignment (Talavera & Castresana, 2007). The evolutionary history of these viruses was then determined using the maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic method available in PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., 2010), incorporating 1000 bootstrap replicates to determine the robustness. The best-fit LG+Γ model of amino acid substitution was selected for both Gag and Pol using the ProtTest program (Abascal et al., 2005).

Table 3.

Gammaretroviruses used in the phylogenetic analyses

| Virus | Abbreviation | GenBank accession no. | Host |

| Reticuloendotheliosis virus | REV | NC_006934 | Bird |

| Pre-xenotropic MuLV-related virus 1 and 2 | PreXMRV-1/2* | NC_007815 | Mouse |

| Feline leukemia virus | FeLV | NC_001940 | Cat |

| Gibbon ape leukemia virus | GALV | NC_001885 | Gibbon ape |

| Friend murine leukemia virus | F-MuLV | NC_001362 | Mouse |

| Moloney murine leukemia virus | M-Mulv | NC_001501 | Mouse |

| Rauscher murine leukemia virus | R-MuLV | NC_001819 | Mouse |

| Murine type C retrovirus | M-CRV | NC_001702 | Mouse |

| Porcine endogenous retrovirus A | PERV-A | AJ293656 | Pig |

| Porcine endogenous retrovirus B | PERV-B | AY099324 | Pig |

| Porcine endogenous type C retrovirus | PERV-C | EF133960 | Pig |

| Feline RD114 retrovirus | RD114 | NC_009889 | Cat |

| M. dunni endogenous virus | MDEV | AF053745 | Mouse |

| Phascolarctos cinereus retrovirus | KoRV | AF151794 | Koala |

| Orcinus orca endogenous retrovirus | OOEV | GQ222416 | Whale |

| Baboon endogenous virus | BaEV | D10032 | Non-human primates |

| R. ferrumequinum retrovirus | RfRV† | JQ303225 | R. ferrumequinum |

| R. pusillus rerovirus | RpuRV† | JQ292909 | R. pusillus |

| R. pearsoni rerovirus | RpeRV† | JQ292914 | R. pearsoni |

| R. megaphyllus rerovirus | RmRV† | JQ292911 | R. megaphyllus |

| R. affinis rerovirus | RaRV† | JQ292913 | R. affinis |

| M. ricketti retrovirus | MrRV† | JQ292912 | M. ricketti |

| P. alecto retrovirus | PaRV† | JQ292910 | P. alecto |

Recombined strain (Paprotka et al., 2011).

These bat gammaretroviruses were reported by Cui et al. (2012).

Molecular dating of bat gammaretroviral invasions.

Rates of evolutionary change in the genomes of megabats (Pteropus, Rousettus, Cynopterus and Nyctimene, representing the Pteropodidae) and microbats (Antrozous, Rhogeessa and Myotis, representing three closely related species in the Vespertilionoidea family) were estimated using 11 concatenated nuclear genes (Teeling et al., 2005): ADORA3, ADRB2, APP, ATP7A, BDNF, BMI, CREM, EDG1, PLCB4, PNOC and TYR (totalling 4869 bp for megabats and 4803 bp for microbats). Nucleotide substitution rates in these data were estimated using beast v1.7 (Drummond et al., 2012), as described by Katzourakis et al. (2009). Divergence times of the various bat species were taken from the fossil record (Teeling et al., 2005) and used to calibrate the timescale of the beast phylogeny assuming an uncorrelated lognormal relaxed molecular clock. The divergence times used as calibration points were: Pteropus and Rousettus, mean of 23 Mya (range 28–18 Mya); Cynopterus and Nyctimene, 22 Mya (27–18 Mya); Pteropus and Rousettus, and Cynopterus and Nyctimene, 24 Mya (29–20 Mya); Antrozous and Rhogeessa, 10 Mya (13–7 Mya) and Antrozous and Rhogeessa, and Myotis, 20 Mya (25–16 Mya). All phylogenetic trees were inferred using the GTR substitution model and the Yule speciation prior, and the beast analyses were run until all relevant parameters converged, with 10 % of the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo chains discarded as burn-in.

The sequences of retroviral LTRs are useful indicators of ERV integration times, as the two LTRs are identical at the point of integration, after which they diverge and evolve independently of each other (Dangel et al., 1995). Based on these assumptions, we used the evolutionary rates for the bat genomic DNA determined above to date the invasion of gammaretroviruses into bat genomes using their 5′ and 3′ LTR sequences. This analysis involved the relation T = (D/R)/2, where T is the invasion time (million years), D is the number of differences per site among the LTRs as estimated by ltr_finder (Xu & Wang, 2007) and R is the genomic substitution rate (substitutions per site year−1).

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgements

We thank Lina Wang and Mengyao Dai (Institute of Molecular Ecology and Evolution, East China Normal University) for experimental support. G. T. was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Senior Research Fellowship 543105 and the Victorian Operational Infrastructure Support Program was received by the Burnet Institute. L.-F. W. was supported by the CSIRO Office of the Chief Executive via an OCE Science Leader Award.

Footnotes

The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers for the RlRV and MlRV sequences reported in this paper are JQ951955–JQ951958.

A supplementary figure is available with the online version of this paper.

References

- Abascal F., Zardoya R., Posada D. ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2104–2105. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calisher C. H., Childs J. E., Field H. E., Holmes K. V., Schountz T. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:531–545. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00017-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua K. B., Crameri G., Hyatt A., Yu M., Tompang M. R., Rosli J., McEachern J., Crameri S., Kumarasamy V., other authors A previously unknown reovirus of bat origin is associated with an acute respiratory disease in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11424–11429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701372104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin J. M., Hughes S. H., Varmus H. E. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Holmes E. C. Endogenous lentiviruses in the ferret genome. J Virol. 2012;86:3383–3385. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06652-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Counor D., Shen D., Sun G., He H., Deubel V., Zhang S. Detection of Japanese encephalitis virus antibodies in bats in Southern China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:1007–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Tachedjian M., Wang L., Tachedjian G., Wang L. F., Zhang S. Discovery of retroviral homologs in bats: implications for the origin of mammalian gammaretroviruses. J Virol. 2012;86:4288–4293. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06624-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangel A. W., Baker B. J., Mendoza A. R., Yu C. Y. Complement component C4 gene intron 9 as a phylogenetic marker for primates: long terminal repeats of the endogenous retrovirus ERV-K(C4) are a molecular clock of evolution. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:41–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00164986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler J. F., Corman V. M., Müller M. A., Maganga G. D., Vallo P., Binger T., Gloza-Rausch F., Rasche A., Yordanov S., other authors Bats host major mammalian paramyxoviruses. Nat Commun. 2012;3:796. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Suchard M. A., Xie D., Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the beast 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012 doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field H. E., Mackenzie J. S., Daszak P. Henipaviruses: emerging paramyxoviruses associated with fruit bats. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;315:133–159. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford R., Tristem M. The evolution, distribution and diversity of endogenous retroviruses. Virus Genes. 2003;26:291–315. doi: 10.1023/A:1024455415443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. F., Coffin J. M. Evidence for genomic rearrangements mediated by human endogenous retroviruses during primate evolution. Nat Genet. 2001;29:487–489. doi: 10.1038/ng775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jern P., Coffin J. M. Effects of retroviruses on host genome function. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:709–732. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzourakis A., Gifford R. J., Tristem M., Gilbert M. T., Pybus O. G. Macroevolution of complex retroviruses. Science. 2009;325:1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1174149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin I. V., Hughes G. J., Rupprecht C. E. Phylogenetic relationships of seven previously unclassified viruses within the family Rhabdoviridae using partial nucleoprotein gene sequences. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2323–2331. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81879-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., other authors clustal w and clustal_x version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S. K., Woo P. C., Li K. S., Huang Y., Tsoi H. W., Wong B. H., Wong S. S., Leung S. Y., Chan K. H., Yuen K. Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14040–14045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy E. M., Kumulungui B., Pourrut X., Rouquet P., Hassanin A., Yaba P., Délicat A., Paweska J. T., Gonzalez J. P., Swanepoel R. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 2005;438:575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Shi Z., Yu M., Ren W., Smith C., Epstein J. H., Wang H., Crameri G., Hu Z., other authors Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paprotka T., Delviks-Frankenberry K. A., Cingöz O., Martinez A., Kung H. J., Tepper C. G., Hu W. S., Fivash M. J., Jr, Coffin J. M., Pathak V. K. Recombinant origin of the retrovirus XMRV. Science. 2011;333:97–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1205292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sverdlov E. D. Retroviruses and primate evolution. Bioessays. 2000;22:161–171. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200002)22:2<161::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera G., Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56:564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeling E. C., Springer M. S., Madsen O., Bates P., O’Brien S. J., Murphy W. J. A molecular phylogeny for bats illuminates biogeography and the fossil record. Science. 2005;307:580–584. doi: 10.1126/science.1105113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisset C., Weiss R. A., Griffiths D. J. Human RNA “rumor” viruses: the search for novel human retroviruses in chronic disease. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:157–196. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00033-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R. A. The discovery of endogenous retroviruses. Retrovirology. 2006;3:67. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S., Lau S., Woo P., Yuen K. Y. Bats as a continuing source of emerging infections in humans. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:67–91. doi: 10.1002/rmv.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Wang H. ltr_finder: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W265–W268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.