Abstract

Cardiovascular disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a uremic metabolite that is elevated in the setting of CKD, has been implicated as a nontraditional risk factor for cardiovascular disease. While association studies have linked elevated plasma levels of TMAO to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, its direct effect on cardiac and smooth muscle function remains to be fully elucidated. We hypothesized that pathological concentrations of TMAO would acutely increase cardiac and smooth muscle contractility. These effects may ultimately contribute to cardiac dysfunction during CKD. High levels of TMAO significantly increased paced, ex vivo human cardiac muscle biopsy contractility (P < 0.05). Similarly, TMAO augmented contractility in isolated mouse hearts (P < 0.05). Reverse perfusion of TMAO through the coronary arteries via a Langendorff apparatus also enhanced cardiac contractility (P < 0.05). In contrast, the precursor molecule, trimethylamine (TMA), did not alter contractility (P > 0.05). Multiphoton microscopy, used to capture changes in intracellular calcium in paced, adult mouse hearts ex vivo, showed that TMAO significantly increased intracellular calcium fluorescence (P < 0.05). Interestingly, acute administration of TMAO did not have a statistically significant influence on isolated aortic ring contractility (P > 0.05). We conclude that TMAO directly increases the force of cardiac contractility, which corresponds with TMAO-induced increases in intracellular calcium but does not acutely affect vascular smooth muscle or endothelial function of the aorta. It remains to be determined if this acute inotropic action on cardiac muscle is ultimately beneficial or harmful in the setting of CKD.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We demonstrate for the first time that elevated concentrations of TMAO acutely augment myocardial contractile force ex vivo in both murine and human cardiac tissue. To gain mechanistic insight into the processes that led to this potentiation in cardiac contraction, we used two-photon microscopy to evaluate intracellular calcium in ex vivo whole hearts loaded with the calcium indicator dye Fluo-4. Acute treatment with TMAO resulted in increased Fluo-4 fluorescence, indicating that augmented cytosolic calcium plays a role in the effects of TMAO on force production. Lastly, TMAO did not show an effect on aortic smooth muscle contraction or relaxation properties. Our results demonstrate novel, acute, and direct actions of TMAO on cardiac function and help lay the groundwork for future translational studies investigating the complex multiorgan interplay involved in cardiovascular pathogenesis during CKD.

Keywords: calcium homeostasis, cardiac muscle, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, vascular smooth muscle

INTRODUCTION

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 30 million adults in the United States are living with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (77). As kidney function deteriorates, metabolic waste accumulates within the body, leading to widespread homeostatic disturbances, including cardiovascular dysfunction (6). More than 60% of individuals with CKD have comorbid cardiovascular disease (CVD) (76) with a dramatic increase in the prevalence as CKD advances (20). Standard clinical interventions for managing CVD have failed to improve cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CKD (4, 34). Thus, CVD is the leading cause of mortality among patients with CKD, accounting for ~50% of deaths in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (31, 43).

There is a novel appreciation of the intestinal microbiota functioning as an endocrine organ capable of producing a myriad of metabolites related to human health and disease (62). Evolving evidence suggests that resident intestinal bacteria are obligatory contributors to several key metabolic pathways linked to chronic cardiometabolic conditions (3, 13, 61). One such microbiome-derived metabolite, which may have important implications for cardiovascular health, is trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO). Formation of TMAO occurs in the liver and entails gut microbial metabolism of trimethylamine (TMA) from dietary choline and l-carnitine (28, 71). These precursor metabolites are primarily consumed in the form of fatty, high-cholesterol foods such as red meat, liver, and egg yolks (61); however, TMAO can also be attained directly from some seafood sources (68). There is a strong inverse relationship between kidney function and serum TMAO levels (5, 7, 40), as its clearance is dependent almost exclusively on urinary excretion (2, 41, 60). As such, serum concentrations for patients with dialysis-dependent CKD are observed to be markedly elevated over the general population. A study by Stubbs et al. analyzing the EVOLVE clinical trial cohort reported the highest quintile of dialysis patients with serum TMAO in the range of ~150 µM to 1.1 mM (58), whereas in individuals with normal kidney function levels are typically below 5 µM (57).

TMAO has been implicated as a nontraditional risk factor for CVD in patients with CKD (8, 54, 64). Yet, the exact mechanisms by which TMAO potentially facilitates CVD have not been defined. Animal studies suggest TMAO promotes atherosclerotic plaque formation (28, 71). While proatherogenic properties could potentially account for the clinical associations between TMAO and CVD (61, 65, 72), direct effects of elevated levels of TMAO on arterial smooth muscle contraction and relaxation are unknown. Moreover, recent evidence indicates elevated TMAO levels directly induce cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis (32, 33, 75). Elevated levels of TMAO correlate with equivalent adverse prognostic value in both ischemic and nonischemic heart disease (63), suggesting TMAO may contribute to cardiovascular pathogenesis beyond atherosclerotic complications and needs to be investigated.

Studies exploring the direct effects of TMAO on human and animal myocardium and vasculature are limited. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to determine how TMAO alters cardiac contractile function and calcium handling and arterial smooth muscle function. We hypothesized that pathological concentrations of TMAO would acutely increase cardiac and smooth muscle contractility. These effects may ultimately contribute to cardiac dysfunction during CKD. We investigated the direct effects of TMAO on human cardiac muscle biopsies and isolated mouse heart contractile function, as well as its ability to acutely influence intracellular calcium within the myocardium. Moreover, we examined aortic smooth muscle contraction and relaxation properties in the presence of high concentration of TMAO. The results expand our understanding of the relationships among TMAO, cardiovascular function, and CVD risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Participants

Under the approval of the University of Kansas Medical Center Human Subjects Committee (Institutional Review Board No. 00004440), atrial appendage cardiac tissue was obtained from the Cardiovascular Research Institute at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Subject qualifying criteria included being 18 yr of age or older and undergoing an open-heart procedure requiring cardiopulmonary bypass (including coronary artery bypass grafting, cardiac valvular repair/replacement, and repair of septal defects). Participation was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained before enrollment in the study. Subjects were fully informed of the risks and benefits of participation. There was no reimbursement for patient participation. All adult subjects regardless of age, race, or sex were included in this study. Non-English speaking persons were excluded so that there would be no confusion during informed consent. No vulnerable populations (e.g., children, pregnant women, prisoners, or decisionally impaired subjects) were included. Subjects were able to withdraw their consent any time before the surgical procedure. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) was used to securely store patient health information data. Demographic information on the subjects from which the samples were obtained is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subject demographics at the time of atrial appendage biopsy retrieval

| Treatment | Age | Sex | Race | Past Medical History | β-Blocker | Amlodipine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | ||||||

| Subject 1 | 71 | Man | Caucasian | CAD, HTN, DM2 | ||

| Subject 2 | 59 | Man | Caucasian | CAD, HTN, HLD | X | |

| Subject 3 | 59 | Man | Caucasian | CAD, HTN, HLD | ||

| Subject 4 | 58 | Man | Caucasian | CAD, HTN, DM2, HLD, previous MI | X | |

| Subject 5 | 46 | Man | Caucasian | CAD, HTN, HLD | X | |

| TMAO | ||||||

| Subject 6 | 45 | Woman | African American | CAD, HTN, AI, CKD | X | |

| Subject 7 | 54 | Woman | Caucasian | CAD, HTN, DM2 | ||

| Subject 8 | 58 | Man | Caucasian | CAD, HTN, DM2, HLD, ESRD | X | X |

| Subject 9 | 59 | Man | Caucasian | CAD, HTN, DM2, HLD, CKD | X |

TMAO, trimethylamine-N-oxide (3 mM); CAD, coronary artery disease; HTN, hypertension; DM2, type 2 diabetes mellitus; HLD, hyperlipidemia; MI, myocardial infarction; AI, aortic insufficiency; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Experimental Animals

Twelve-week-old male CD-1 mice (Harlan, Madison, WI) and male Sprague-Dawley rats were used for ex vivo heart contractility experiments and aorta studies, respectively. All animals were housed in a temperature-controlled (22 ± 2°C) room with a 12-h:12-h light-dark cycle. Animals were allowed ad libitum access to food and water. Mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane inhalation before tissue harvesting. All protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) School of Medicine.

Cardiac Muscle Contractility: Human

Testing of atrial appendage biopsy tissue was approved by the UMKC Institutional Biosafety Committee (No. 16-17). Atrial appendage biopsy tissue was obtained before cannula placement during the cardiopulmonary bypass procedure. Once retrieved, the piece of tissue was placed in a sterile tube containing normal saline. This tube was placed on ice to reduce tissue metabolism during transportation to the laboratory. In the laboratory, the heart tissue was placed in Ringer’s solution consisting of (in mM) 140 NaCl, 2.0 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.0 MgSO4, 1.5 K2HPO4, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4), as previously described (70), and carefully cleaned of any connective tissue before being cut into two or three muscle strips depending on the size of the biopsy. The strips were hung vertically, attached to a force transducer between bipolar platinum-stimulating electrodes suspended in 25-ml glass tissue chambers (Radnoti, Monrovia, CA), and bubbled under 100% O2. All contractility experiments were performed at room temperature. The muscle strips were stretched to the length of maximum force development and stimulated (SD9 stimulation unit, Grass Technologies, Quincy, MA) with pulses of 1 Hz at 5-ms duration at a voltage that produced submaximal contraction (~40 V). For each experiment, TMAO (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) was freshly prepared by dissolving into Ringer’s solution to create a 1 M stock solution and diluted in Ringer’s solution to 100× working concentrations before addition to the organ bath chambers. Hearts were paced for 20 min to obtain a stable baseline before treatment with either an equivalent volume of vehicle (Ringer’s solution) or 3 mM TMAO. Following treatment with either vehicle or TMAO, norepinephrine (5 µM) was administered as a positive control, as stimulation of the β1-receptor in the heart is known to increase cardiac muscle contraction (1). The contractile data were recorded on LabChart 7 software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Contraction waveform changes were analyzed for peak isometric tension (mN), maximum slope (mN/s), and minimum slope (−mN/s) after vehicle or TMAO treatment. Experimental data were normalized to baseline contractile parameters and presented as a fold change from baseline.

Cardiac Muscle Contractility: Mouse

Bath application.

The mouse hearts were quickly excised and placed in Ringer’s solution. The atria, blood, fat, and excess connective tissues were carefully removed. The hearts were hung vertically, attached to a force transducer between bipolar platinum-stimulating electrodes within the 25-ml glass tissue chambers, and oxygenated with 100% O2. Hearts were paced and allowed to stabilize as previously mentioned for human cardiac muscle, before treatment with either vehicle (Ringer’s solution) or TMAO. Two concentrations of TMAO (300 µM and 3 mM) were pipetted into the organ bath 30 min apart. As a control, equal volumes of vehicle (Ringer’s solution) were administered 30 min apart. Norepinephrine (5 µM) was used as a positive control. Contractility was measured, and the contractile parameters were analyzed as previously mentioned for human cardiac muscle.

Langendorff perfusion.

As a follow-up approach, mouse hearts were reverse perfused through the aorta via a Langendorff apparatus to facilitate TMAO delivery directly into the myocardium. After isolation of the heart, the atria were removed and the ascending aorta was cannulated to establish access for reverse perfusion of the coronary circulation via a Langendorff perfusion setup using a peristaltic pump (Masterflex, 7518-00, Cole-Parmer Instrument Company, Vernon Hills, IL). The cannulated hearts were hung and attached to a force transducer as previously described (Fig. 3A). Retrograde perfusion of the hearts was initiated with Ringer’s solution equilibrated with 100% O2 (pH 7.4). Hearts were stimulated with pulses of 1.0–1.5 Hz at 5-ms duration and allowed to stabilize for 20 min before perfusion with either an equivalent volume of vehicle (Ringer’s solution) or TMAO (3–300 µM). In a separate series of experiments, TMA (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) was freshly prepared from stock solution (45% wt/vol) to 100× working concentrations and tested on hearts at 30 and 300 µM. Moreover, doses of 300 µM and 3 mM d-mannitol (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) were included as an osmolarity control. Norepinephrine was used as a positive control following TMAO or vehicle perfusion. Contractility was measured as previously mentioned.

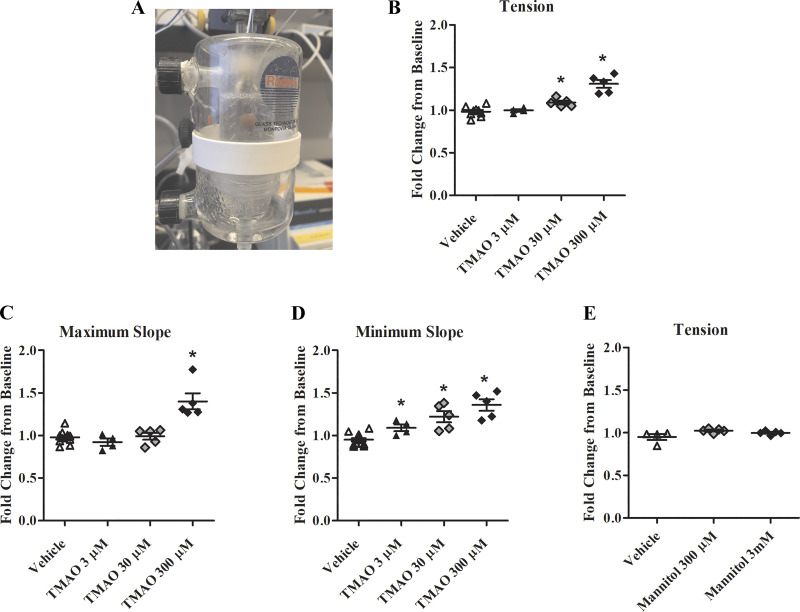

Fig. 3.

Perfusion of the coronary circulation with trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) increases contractility. A: Langendorff perfusion apparatus: a cannula inserted into the aorta facilitates perfusion of the coronary circulation while the heart is connected to the force transducer and hung between bipolar stimulating electrodes. B: change in isometric tension normalized to baseline contractions (n = 4–13). C: change in maximum slope normalized to baseline contractions (n = 4–13). D: change in minimum slope normalized to baseline contractions (n = 4–13). E: change in isometric tension normalized to baseline contraction after perfusion with d-mannitol. *P < 0.05, statistical difference from vehicle.

Multiphoton Calcium Imaging: Paced Mouse Hearts

Isolated mouse hearts were Langendorff perfused as described above. Retrograde perfusion of the hearts was initiated with Ringer’s solution equilibrated with 100% O2 (pH 7.4) for ~10 min or until the solution was free of extraneous blood. The hearts were then perfused with Ringer’s solution with 5 µM Fluo-4 AM for 30 min, followed by Ringer’s solution with 20 mM 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM) for 20 min to allow for dye deesterification and inhibition of heart contractions. The heart was then removed from the perfusion apparatus, pinned (at the apex and aorta) to the bottom of silicone-lined petri dish, and fully submerged under 40 mL of Ringer’s solution with 20 mM BDM. Hearts were stimulated at 1 Hz (50 V; 5-ms duration) for the duration of imaging; cardiomyocytes were distinguished by the presence of calcium waves during pacing. Calcium imaging was conducted using a multiphoton SP8 MP microscope (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) with a 10× water immersion objective (numerical aperture = 0.30) at an excitation wavelength of 820 nm. After a baseline recording was captured, either 500 µL of a solution of TMAO in Ringer’s solution (final concentration, 300 µM) or 500 µL of Ringer’s solution (vehicle 1) was added to the edge of the petri dish. Fluorescence was captured for 2 min every 5 min for 20 min. After 20 min, either 500 µL TMAO (final concentration, 3 mM) or another 500 µL Ringer’s solution (vehicle 2) was added to the petri dish, and fluorescence imaging was repeated as above for an additional 20 min. Norepinephrine (1 µM) was administered as a positive control.

Isolated Aortic Ring Contractions

Rat aortic segments (3 to 4 mm in length) were mounted on pins in chambers of a DMT 610M wire myograph system (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus N, Denmark) containing Krebs buffer consisting of (in mM) 119 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 0.24 NaHCO3, 1.18 KH2PO4, 1.19 MgSO4, 5.5 glucose, and 1.6 CaCl2, saturated at 37°C with a gas mixture containing 20% O2-5% CO2-75% N2 (Airgas Mid-South, Tulsa, OK) at 37°C. Aortic rings were progressively stretched to 1.5 g equivalent force passive tension in 0.25-g steps and allowed to equilibrate for 45 min as previously described (55). Force changes were recorded using an ADInstruments PowerLab 4/30 and associated LabChart Pro software (v. 6.1). Aortic preparations were treated with vehicle (Krebs buffer) or 300 μM TMAO for 30 min while monitoring isometric tension. To induce a contraction response, aortic rings were next exposed to phenylephrine (PE; 1 μM). The contraction response was followed by a concentration response curve to acetylcholine (ACh; 1 nM–100 μM) to evaluate endothelial-mediated relaxation. Similarly, a relaxation response curve was measured after treatment with the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; 100 μM). Contraction data were presented as grams of tension, and relaxation was presented as a percent relaxation compared with the maximal contraction produced by PE.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical procedures were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 (La Jolla, CA). Cardiac contractility data are presented as the average fold change from baseline ± SE to eliminate intersubject/interanimal variability. Data were compared using either an unpaired t-test or a one-way analysis of variance followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison post hoc analysis, with the significance set at the P < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

TMAO-Induced Changes in Human Cardiac Muscle Contraction

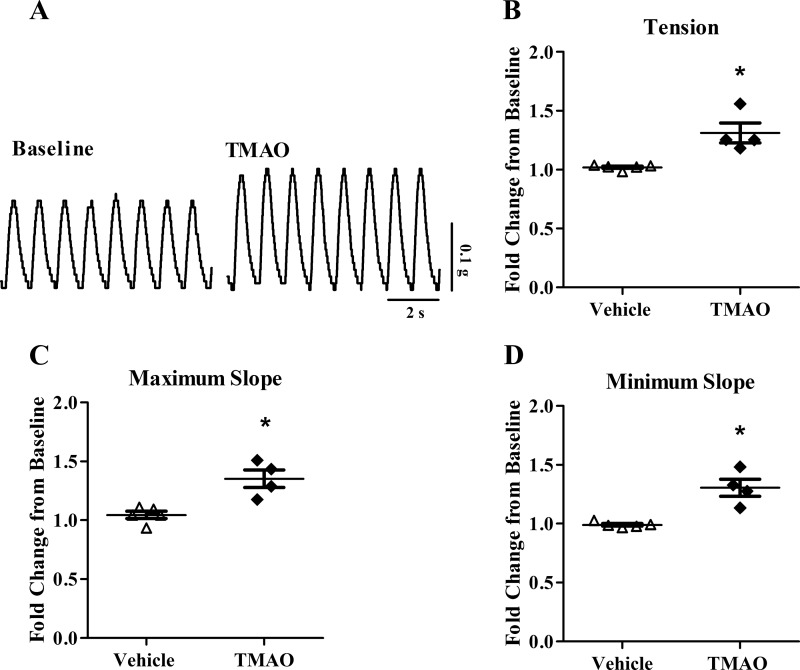

To explore the acute, direct effect of TMAO on human cardiac muscle contractility, TMAO (3 mM) was applied to atrial appendage biopsy tissue. TMAO increased contractile tension (force) 29%, maximum slope (rate of contraction) 31%, and minimum slope (rate of relaxation) 32% compared with vehicle (P < 0.05; Fig. 1). The stimulatory effect of TMAO on contractility was observed to occur rapidly, with peak changes noted in under 20 min. Of note, two subjects in the TMAO group and three subjects in the control group were taking a β-blocker at the time of their enrollment in this study. Although these drugs reduce β-adrenergic receptor activity in vivo, all biopsy samples included for analysis increased at least by 40% from baseline in response to the inotropic agent, norepinephrine, used as a positive control.

Fig. 1.

Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) enhances human cardiac muscle contractility. A: raw tracings of paced, human cardiac biopsy contractions at baseline and following TMAO. B: change in isometric tension normalized to baseline contractions (n = 4 to 5). C: change in maximum slope normalized to baseline contractions (n = 4 to 5). D: change in minimum slope normalized to baseline contractions (n = 4 to 5). *P < 0.05, statistical difference from vehicle. TMAO; 3 mM.

TMAO-Induced Changes in Mouse Cardiac Muscle Contraction

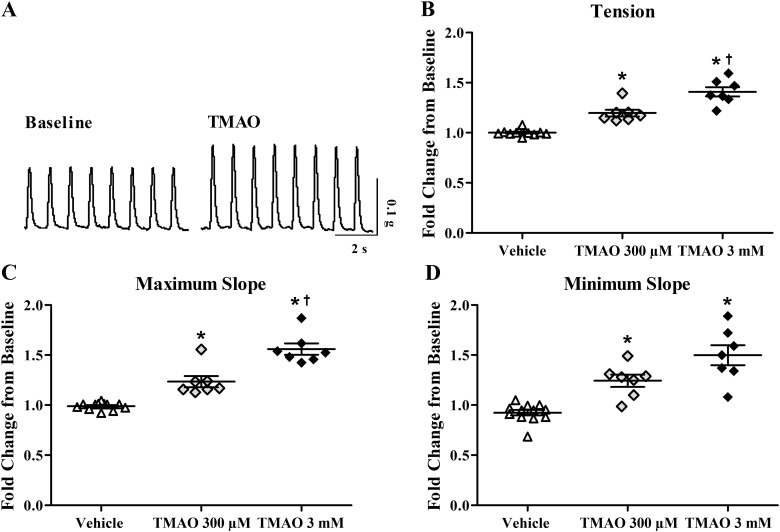

To further characterize the acute actions of TMAO, we repeated our human studies with isolated mouse hearts at the same and lower concentration of TMAO. Figure 2A displays raw contractile tracings following treatment with 3 mM TMAO. Consistent with what was observed in our human study, acute treatment with TMAO increased average isometric tension 20% and 41%, at 300 µM and 3 mM respectively, compared with vehicle (P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Similarly, it increased maximum slope 22% and 55%, at 300 µM and 3 mM, respectively, compared with vehicle (P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). As in human cardiac muscle, TMAO also increased the minimum slope (faster relaxation), 27% and 43%, at 300 µM and 3 mM. respectively, compared with vehicle (P < 0.05; Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Bath application of trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) increases cardiac contractility in isolated mouse hearts. A: raw tracings of paced, ventricular contractions at baseline and following 3 mM TMAO. B: change in isometric tension normalized to baseline contractions (n = 6 to 7). C: change in maximum slope normalized to baseline contractions (n = 6 to 7). D: change in minimum slope normalized to baseline contractions (n = 6 to 7). *P < 0.05, statistical difference from vehicle. †P < 0.05, statistical difference from 300 µM TMAO.

In the next series of experiments, we wanted to compare concentration responses with perfused TMAO through the coronary arteries via Langendorff perfusion. In this setup, TMAO concentrations ranging from 3 µM to 300 µM were examined. TMAO at 30 µM induced a statistically significant increase in contractile tension by 11%, increased minimum slope by 28%, but did not have a significant effect on maximum slope (P < 0.05; Fig. 3, A–D). TMAO at 300 µM increased tension 31%, maximum slope 43%, and minimum slope 36% compared with vehicle (P < 0.05; Fig. 3, A–D). The changes in contractile tension and maximum slope at 300 µM were greater than bath-application of TMAO, at the same dose. Interestingly, although 3 µM TMAO showed no change to contractile tension or maximum slope, there was a statistically significant 15% increase in minimum slope (P < 0.05; Fig. 3D).

To rule out osmolarity changes as a confounding factor in the observed effects of elevated concentrations of TMAO on cardiac contractility, we next tested 300 µM and 3 mM concentrations of the inert sugar molecule, d-mannitol. No changes to cardiac contractility were found for any of the concentrations of d-mannitol (P > 0.05; Fig. 3E).

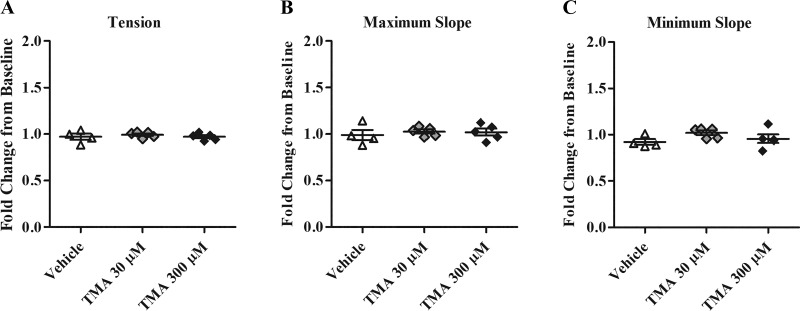

To test the specificity of our TMAO results, a parallel series of Langendorff experiments was undertaken using similar concentrations of TMAO precursor metabolite, TMA. Treatments of 30 µM and 300 µM TMA did not alter cardiac contractility (P > 0.05; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Perfusion of the coronary circulation with trimethylamine (TMA) does not alter contractility. A: change in isometric tension normalized to baseline contractions (n = 4 to 5). B: change in maximum slope normalized to baseline contractions (n = 4 to 5). C: change in minimum slope normalized to baseline contractions (n = 4 to 5).

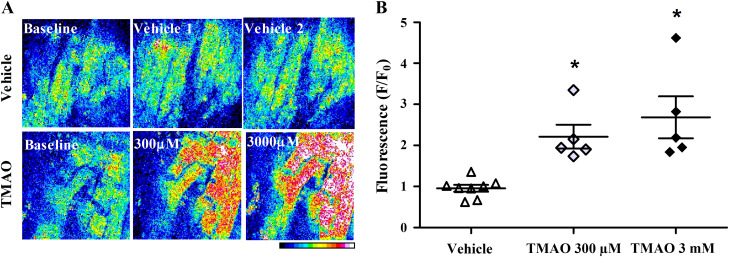

TMAO-Induced Changes in Mouse Myocardial Intracellular Calcium

To explore the effect of TMAO on cellular calcium dynamics, multiphoton microscopy was used to capture changes in intracellular calcium in paced, adult mouse hearts ex vivo. Figure 5A displays TMAO-induced changes in calcium via Fluo-4 AM fluorescence within the left ventricle. TMAO increased intracellular calcium levels by 2.2-fold and 2.7-fold, at 300 µM and 3 mM, respectively, compared with vehicle (P < 0.05; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) increases intracellular calcium in isolated mouse hearts. A: whole hearts were paced and cellular Fluo-4 AM fluorescence measured in the left ventricle using two-photon microscopy following treatments with TMAO or vehicle. The color scale represents increasing fluorescence values from 0 to 255 (maximum). B: change in the average Fluo-4 AM fluorescence, normalized to baseline fluorescence (n = 4 to 5). *P < 0.05, statistical difference from vehicle.

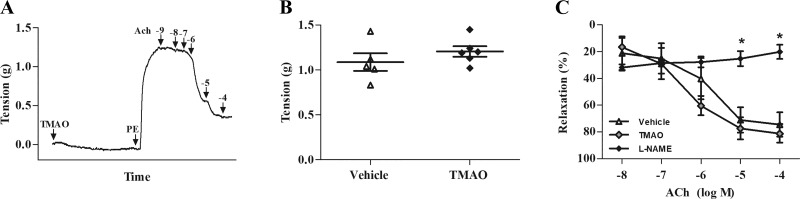

Testing of TMAO on Aortic Ring Contraction

To determine whether high amounts of exogenous TMAO can directly induce vascular smooth muscle contraction or alter drug-induced contraction/relaxation properties, we performed isometric tension myography on isolated aortic ring preparations treated with 300 µM TMAO or vehicle (Fig. 6A). Perfusion of 300 µM TMAO or vehicle directly into the myography chamber did not result in changes to resting muscle tension over the 30-min treatment period. Stimulation with PE and ACh to facilitate contraction and relaxation, respectively, resulted in similar responses among TMAO- and vehicle-pretreated groups (P > 0.05; Fig. 6, B and C). Conversely, treatment with the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, l-NAME, significantly inhibited endothelium-mediated vasorelaxation compared with vehicle and TMAO groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) has no effect on isolated aortic ring contractility. A: representative aortic myography record indicating contractile tension during 30 min perfusion with vehicle or TMAO, followed by 1 µM phenylephrine (PE) to induce contraction, and 1 nM–100 µM of acetylcholine (ACh) to initiate relaxation. B: maximal tension in response to 1 µM PE perfusion in aortic rings treated with vehicle or TMAO. C: percentage of relaxation after perfusion with 10 nM-100 µM ACh in aortic rings treated with vehicle, TMAO, or NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; 100 µM). *P < 0.05, statistical difference from l-NAME (P < 0.05). TMAO, 300 µM.

DISCUSSION

In individuals with healthy renal function, the median serum TMAO concentration is less than 5 µM but can reach up to 1.1 mM as the kidney function deteriorates to the point of end-stage disease (57, 58). Renal excretion of TMAO is believed to primarily occur via cation transporters (OCT-1, OCT-2) (42), which display downregulated tubular expression in CKD rats (29). Additionally, increased hepatic production of TMAO in CKD may result because of enhanced flavin monooxygenase enzyme activity in this setting (27, 49). Elevated circulating levels of TMAO have been implicated as an independent, nontraditional risk factor for CVD in patients with CKD (54, 71) and have been shown to be associated with increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (65, 71, 72), heart failure (66, 67), and mortality (40, 64), even after accounting for traditional risk factors. Despite these strong clinical associations, the mechanism by which TMAO promotes cardiovascular risk remains poorly understood. To date, most studies have focused on TMAO as a potential vascular toxin, linking increased plasma TMAO to foam cell formation and altered sterol metabolism (28, 71); yet, few studies have attempted to uncover the direct effects of TMAO on the myocardium or vasculature itself. Therefore, our objective was to determine whether TMAO alone could acutely alter cardiac muscle contractile mechanics and calcium homeostasis within cardiomyocytes or alter smooth muscle function in isolated aortic rings. We have shown for the first time that 1) TMAO directly increases human cardiac muscle contractile force and accelerates the rate of relaxation, 2) these positive inotropic and lusitropic effects can be replicated with isolated mouse hearts, 3) the contractile responses correspond with significant TMAO-induced increases in intracellular calcium in cardiomyocytes, and 4) acute administration of TMAO did not alter aortic smooth muscle contraction or relaxation characteristics.

In our intact heart and heart tissue studies, elevated concentrations of TMAO increased contractile force of both human and mouse cardiac muscle. Specifically, in mouse cardiac muscle, a physiological concentration of 3 µM TMAO showed no impact on cardiac contractile force; however, a concentration-dependent increase in force was observed from 30 µM to 3 mM TMAO. Additional experiments were conducted with up to 3 mM d-mannitol to specifically rule out possible effects to cardiac contractility due to increased buffer osmolarity of high concentrations of TMAO, and no changes to heart contractility were detected. Thus, the increased contractile force in our isolated heart tissue studies is most likely a direct effect of TMAO on the myocardium. Interestingly, a study examining skeletal muscle contractile mechanics in the rainbow smelt, Osmerus mordax, demonstrated that TMAO at 50 mM increased contractile force, power output, and facilitated faster muscle relaxation (16).

There is some evidence to suggest that elevated serum levels of the TMAO precursor molecule, TMA, may also be contributing significantly to development of CVD in kidney disease (24–26). Therefore, we also employed contractility studies using TMA treatments and found no acute effect upon force generation in mouse hearts. While it remains to be determined if TMA alters heart function with more prolonged exposure, we have shown that the contractile response observed in this experimental setting seems to be unique to TMAO.

We also observed an increase in intracellular calcium in ex vivo paced hearts in a similar time course as the increase in contraction force. While calcium may not be the only mechanism by which TMAO increases force, it is likely a major player in our studies. The specific mechanism by which TMAO increases intracellular calcium remains to be explored. Nevertheless, it is possible that TMAO may directly or indirectly alter ion channel function (such as calcium channels). There is robust evidence that owing to its small size and a combination of both hydrophobic and polar characteristics (9), TMAO mimics a protein chaperone and therefore promotes protein stability and function (36, 59). In a mouse model of cystic fibrosis, TMAO was shown to promote the defective chloride transporter’s folding and maturation, partially restoring its function (19). If TMAO alters open probability of ion channels such as the L-type calcium channel, it would lead to increased calcium influx and calcium-induced calcium release, resulting in greater cytosolic calcium (46).

Interestingly, we observed an increase in the rate of relaxation of the contraction in our ex vivo heart preparations after the addition of TMAO. Beyond its direct role in modulating contractile proteins, calcium binds to numerous other intracellular moieties that fine tune the excitation-contraction coupling mechanism (18). For instance, local changes in calcium concentration induce activation of the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) (39), which in turn can phosphorylate a wide range of key regulatory proteins such as L-type calcium channels, ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2), and the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA)-inhibitory protein phospholamban (37). Phosphorylation of all of these proteins can lead to changes in calcium handling, contractility, and speed of relaxation (10, 11, 23, 30, 73, 74). Direct modulation of SERCA or the SERCA inhibitor, phospholamban, through interaction with TMAO is also a possible mechanism for its direct effects on muscle relaxation kinetics. Recently, endoplasmic reticulum stress kinase, PERK, has been identified to directly bind TMAO and play a key role in development of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response (15).

Aortic Contractions

TMAO is progressively becoming considered as a risk factor for the development of hypertension and endothelial dysfunction in humans (21). In vivo animal studies have revealed that TMAO administration promotes vascular inflammation (53, 56) and atherosclerotic formations (71). While the aforementioned findings implicate TMAO in cardiovascular pathogenesis with prolonged TMAO exposure, little investigation regarding the acute effects of increased TMAO concentration on vasculature function has been undertaken. Since TMAO altered cardiac muscle contractions, we were interested whether TMAO also altered vascular smooth muscle contraction. We found that acute treatment with elevated concentrations of TMAO did not independently induce aortic smooth muscle contraction, alter phenylephrine-induced contractile ability, or impair endothelium-mediated smooth muscle relaxation with acetylcholine. This indicates that TMAO does not likely acutely affect calcium dynamics of vascular smooth muscle of the aorta or interfere with bioavailability of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. Similar to our findings, recent studies have reported a lack of an effect of acute administration of TMAO on arterial blood pressure in vivo or smooth muscle cell viability (24, 26). Likely, TMAO may require chronic exposure for vascular dysfunction to manifest or exhibit acute effects on the vasculature in the presence of additional uremic toxins and/or within the context of certain pathological environments.

Significance

There is a growing appreciation for the intricacy of the relationship between the microbiome, kidneys, and cardiovascular system. Clinical association studies suggest TMAO plays an important role in this multiorgan cross talk, yet the importance of the direct impact TMAO has on the heart itself is only now being explored. At present, it is unclear whether TMAO is a harmful byproduct or whether it may provide some protective benefit in CKD (45).

In a recent study, it was shown that even a moderate increase in plasma TMAO through increased dietary intake can reduce diastolic dysfunction in pressure-overloaded hearts in rats (22). This implies that the relationship between increased TMAO and cardiovascular risk may not be causative, but instead that elevations in TMAO may be a compensatory mechanism to maintain cardiac output during early uremic cardiomyopathy. Interestingly, among patients without diabetes and with CKD stages 2 to 4, there is no difference in left ventricular ejection fraction compared with healthy controls, despite increased myocardial fibrosis and global cardiac strain (17). In light of our findings, TMAO-enhanced contractility may allow for preservation of cardiac output and renal perfusion during early stages of renal dysfunction.

However, chronically elevated contractility and intracellular calcium, while helping to maintain cardiac output, increase cardiac energy consumption and result in pathological changes including cardiac remodeling, hypertrophy, fibrosis, and eventual progression to heart failure (12, 44, 51, 69). These maladaptive changes in cardiac structure and function rise in prevalence as kidney disease progresses into later stages (47). Interestingly, it has been reported that long-term elevations in TMAO in mice led to cardiac inflammation and fibrosis, contributing to impaired cardiac systolic and diastolic function in vivo (14). Similarly, rats that received intraperitoneal injections of 200 µM TMAO for 2 wk had significantly elevated plasma concentrations of TMAO and were found to have increased left ventricular thickness, prominent interstitial fibrosis, and significantly increased atrial natriuretic peptide and β-myosin heavy chain mRNA levels (33), which are hallmarks of cardiac hypertrophy and/or heart failure. On a cellular level, extended exposure to TMAO worsened contractile mechanics and reduced the rate of cytosolic calcium removal, which is a hallmark of failing cardiomyocytes (35, 48). Furthermore, long-term increases in plasma TMAO concentration led to disturbances in both pyruvate and fatty acid oxidation in cardiac mitochondria in mice (38), with TMAO-treated cardiomyocytes exhibiting a higher number of mitochondria and greater lipofuscin-like pigment deposition, suggesting a greater degree of protein oxidative damage (52). Interestingly, a number of reports show a lack of TMAO toxicity in cardiac myocytes. TMAO (up to 100 mM) failed to induce cardiotoxic effects on cells treated in culture for 72 h (25). Moreover, there were no significant changes observed in mitochondrial membrane potential, reactive oxygen species, production, or cell viability after acute and prolonged exposure of rat cardiomyocytes to TMAO (50). These studies suggest that the cardiac response to TMAO may be multifaceted and may be dependent on the chronicity of TMAO exposure, concentration, and the surrounding cellular environment.

In summary, our study is the first to show TMAO has acute inotropic and lusitropic effects on human and mouse cardiac muscle and significantly increases intracellular calcium within the ventricular myocardium. Despite this mechanistic insight, TMAO’s exact means of action for these events remains to be fully elucidated. Nonetheless, our findings lay the groundwork for future translational studies investigating the complex multiorgan interplay involved in cardiovascular pathogenesis and whether TMAO represents a therapeutic target for reducing cardiovascular mortality in patients with CKD.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Award Grant TL1-TR-002368, awarded to the University of Kansas for Frontiers, University of Kansas Clinical and Translational Science Institute (to C. I. Oakley and M. J. Wacker) and the Sarah Morrison Student Research Award at the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) School of Medicine (to C. I. Oakley). The UMKC School of Dentistry Confocal Microscopy Core facility is supported by the UMKC Office of Research Services, UMKC Center of Excellence in Dental and Musculoskeletal Tissues, and National Institutes of Health Grants S10RR027668 and S10OD021665.

DISCLAIMERS

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.I.O., J.A.V., and M.J.W. conceived and designed research; C.I.O., J.A.V., D.W., M.A.G., and L.M.T.-L. performed experiments; C.I.O., J.A.V., D.W., M.A.G., and M.J.W. analyzed data; C.I.O., J.A.V., D.W., T.S., E.D., G.Z., J.R.S., and M.J.W. interpreted results of experiments; C.I.O., J.A.V., D.W., and M.J.W. prepared figures; C.I.O. drafted manuscript; C.I.O., J.A.V., D.W., L.M.T.-L., T.S., E.D., G.Z., J.R.S., and M.J.W. edited and revised manuscript; C.I.O., J.A.V., D.W., M.A.G., L.M.T.-L., T.S., E.D., G.Z., J.R.S., and M.J.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Sarah Dallas (director of the Confocal Microscopy Core at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Dentistry) for assistance; Mozammil Alam and Sarthak Garg for assistance in multiphoton imaging; and Nikita Rafie, Dr. Matthew Hendrix, Dr. David Sanborn, and Lindsey Grant for assistance on this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alhayek S, Preuss CV. Beta 1 receptors [Online]. In: StatPearls Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2020. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532904/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Waiz M, Mitchell SC, Idle JR, Smith RL. The metabolism of 14C-labelled trimethylamine and its N-oxide in man. Xenobiotica 17: 551–558, 1987. doi: 10.3109/00498258709043962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aron-Wisnewsky J, Clément K. The gut microbiome, diet, and links to cardiometabolic and chronic disorders. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 169–181, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, Emberson J, Wheeler DC, Tomson C, Wanner C, Krane V, Cass A, Craig J, Neal B, Jiang L, Hooi LS, Levin A, Agodoa L, Gaziano M, Kasiske B, Walker R, Massy ZA, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Krairittichai U, Ophascharoensuk V, Fellström B, Holdaas H, Tesar V, Wiecek A, Grobbee D, de Zeeuw D, Grönhagen-Riska C, Dasgupta T, Lewis D, Herrington W, Mafham M, Majoni W, Wallendszus K, Grimm R, Pedersen T, Tobert J, Armitage J, Baxter A, Bray C, Chen Y, Chen Z, Hill M, Knott C, Parish S, Simpson D, Sleight P, Young A, Collins R; SHARP Investigators . The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 377: 2181–2192, 2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60739-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bain MA, Faull R, Fornasini G, Milne RW, Evans AM. Accumulation of trimethylamine and trimethylamine-N-oxide in end-stage renal disease patients undergoing haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1300–1304, 2006. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bargman JM, Skorecki KL. Chronic kidney disease. In: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, ed by Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell JD, Lee JA, Lee HA, Sadler PJ, Wilkie DR, Woodham RH. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of blood plasma and urine from subjects with chronic renal failure: identification of trimethylamine-N-oxide. Biochim Biophys Acta 1096: 101–107, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(91)90046-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett BJ, de Aguiar Vallim TQ, Wang Z, Shih DM, Meng Y, Gregory J, Allayee H, Lee R, Graham M, Crooke R, Edwards PA, Hazen SL, Lusis AJ. Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell Metab 17: 49–60, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennion BJ, Daggett V. Counteraction of urea-induced protein denaturation by trimethylamine N-oxide: a chemical chaperone at atomic resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6433–6438, 2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308633101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 415: 198–205, 2002. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaich A, Welling A, Fischer S, Wegener JW, Köstner K, Hofmann F, Moosmang S. Facilitation of murine cardiac L-type Ca(v)1.2 channel is modulated by calmodulin kinase II-dependent phosphorylation of S1512 and S1570. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10285–10289, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914287107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Böhm M, Swedberg K, Komajda M, Borer JS, Ford I, Dubost-Brama A, Lerebours G, Tavazzi L; SHIFT Investigators . Heart rate as a risk factor in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): the association between heart rate and outcomes in a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 376: 886–894, 2010. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown JM, Hazen SL. The gut microbial endocrine organ: bacterially derived signals driving cardiometabolic diseases. Annu Rev Med 66: 343–359, 2015. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-060513-093205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen K, Zheng X, Feng M, Li D, Zhang H. Gut microbiota-dependent metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide contributes to cardiac dysfunction in western diet-induced obese mice. Front Physiol 8: 139, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S, Henderson A, Petriello MC, Romano KA, Gearing M, Miao J, Schell M, Sandoval-Espinola WJ, Tao J, Sha B, Graham M, Crooke R, Kleinridders A, Balskus EP, Rey FE, Morris AJ, Biddinger SB. Trimethylamine N-oxide binds and activates PERK to promote metabolic dysfunction. Cell Metab 30: 1141–1151.e5, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coughlin DJ, Long GM, Gezzi NL, Modi PM, Woluko KN. Elevated osmolytes in rainbow smelt: the effects of urea, glycerol and trimethylamine oxide on muscle contractile properties. J Exp Biol 219: 1014–1021, 2016. doi: 10.1242/jeb.135269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards NC, Moody WE, Yuan M, Hayer MK, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, Steeds RP. Diffuse interstitial fibrosis and myocardial dysfunction in early chronic kidney disease. Am J Cardiol 115: 1311–1317, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabiato A. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol 245: C1–C14, 1983. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer H, Fukuda N, Barbry P, Illek B, Sartori C, Matthay MA. Partial restoration of defective chloride conductance in DeltaF508 CF mice by trimethylamine oxide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L52–L57, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.1.L52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaita D, Mihaescu A, Schiller A. Of heart and kidney: a complicated love story. Eur J Prev Cardiol 21: 840–846, 2014. doi: 10.1177/2047487312462826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ge X, Zheng L, Zhuang R, Yu P, Xu Z, Liu G, Xi X, Zhou X, Fan H. The gut microbial metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide and hypertension risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Adv Nutr 11: 66–76, 2020. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huc T, Drapala A, Gawrys M, Konop M, Bielinska K, Zaorska E, Samborowska E, Wyczalkowska-Tomasik A, Pączek L, Dadlez M, Ufnal M. Chronic, low-dose TMAO treatment reduces diastolic dysfunction and heart fibrosis in hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H1805–H1820, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00536.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudmon A, Schulman H, Kim J, Maltez JM, Tsien RW, Pitt GS. CaMKII tethers to L-type Ca2+ channels, establishing a local and dedicated integrator of Ca2+ signals for facilitation. J Cell Biol 171: 537–547, 2005. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaworska K, Bielinska K, Gawrys-Kopczynska M, Ufnal M. TMA (trimethylamine), but not its oxide TMAO (trimethylamine-oxide), exerts haemodynamic effects: implications for interpretation of cardiovascular actions of gut microbiome. Cardiovasc Res 115: 1948–1949, 2019. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaworska K, Hering D, Mosieniak G, Bielak-Zmijewska A, Pilz M, Konwerski M, Gasecka A, Kapłon-Cieślicka A, Filipiak K, Sikora E, Hołyst R, Ufnal M. TMA, A Forgotten Uremic Toxin, but Not TMAO, Is Involved in Cardiovascular Pathology. Toxins (Basel) 11: 490, 2019. doi: 10.3390/toxins11090490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaworska K, Konop M, Hutsch T, Perlejewski K, Radkowski M, Grochowska M, Bielak-Zmijewska A, Mosieniak G, Sikora E, Ufnal M. TMA but not TMAO increases with age in rat plasma and affects smooth muscle cells viability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci glz181, 2019. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson C, Prokopienko AJ, West RE 3rd, Nolin TD, Stubbs JR. Decreased kidney function is associated with enhanced hepatic flavin monooxygenase activity and increased circulating trimethylamine N-oxide concentrations in mice. Drug Metab Dispos 46: 1304–1309, 2018. doi: 10.1124/dmd.118.081646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, DiDonato JA, Chen J, Li H, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Warrier M, Brown JM, Krauss RM, Tang WH, Bushman FD, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med 19: 576–585, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komazawa H, Yamaguchi H, Hidaka K, Ogura J, Kobayashi M, Iseki K. Renal uptake of substrates for organic anion transporters Oat1 and Oat3 and organic cation transporters Oct1 and Oct2 is altered in rats with adenine-induced chronic renal failure. J Pharm Sci 102: 1086–1094, 2013. doi: 10.1002/jps.23433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, Hamilton SL. Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a003996, 2010. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levey AS, Beto JA, Coronado BE, Eknoyan G, Foley RN, Kasiske BL, Klag MJ, Mailloux LU, Manske CL, Meyer KB, Parfrey PS, Pfeffer MA, Wenger NK, Wilson PW, Wright JT Jr. Controlling the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease: what do we know? What do we need to learn? Where do we go from here? National Kidney Foundation Task Force on Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 853–906, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(98)70145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X, Geng J, Zhao J, Ni Q, Zhao C, Zheng Y, Chen X, Wang L. Trimethylamine N-oxide exacerbates cardiac fibrosis via activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Front Physiol 10: 866, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Wu Z, Yan J, Liu H, Liu Q, Deng Y, Ou C, Chen M. Gut microbe-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide induces cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Lab Invest 99: 346–357, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41374-018-0091-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu M, Li XC, Lu L, Cao Y, Sun RR, Chen S, Zhang PY. Cardiovascular disease and its relationship with chronic kidney disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 18: 2918–2926, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lou Q, Janks DL, Holzem KM, Lang D, Onal B, Ambrosi CM, Fedorov VV, Wang I-W, Efimov IR. Right ventricular arrhythmogenesis in failing human heart: the role of conduction and repolarization remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H1426–H1434, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00457.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma J, Pazos IM, Gai F. Microscopic insights into the protein-stabilizing effect of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 8476–8481, 2014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403224111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maier LS, Bers DM. Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) in excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Cardiovasc Res 73: 631–640, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makrecka-Kuka M, Volska K, Antone U, Vilskersts R, Grinberga S, Bandere D, Liepinsh E, Dambrova M. Trimethylamine N-oxide impairs pyruvate and fatty acid oxidation in cardiac mitochondria. Toxicol Lett 267: 32–38, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mattiazzi A, Vittone L, Mundiña-Weilenmann C. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase: a key component in the contractile recovery from acidosis. Cardiovasc Res 73: 648–656, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Missailidis C, Hällqvist J, Qureshi AR, Barany P, Heimbürger O, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P, Bergman P. Serum trimethylamine-N-oxide is strongly related to renal function and predicts outcome in chronic kidney disease. PLoS One 11: e0141738, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell SC, Zhang AQ, Noblet JM, Gillespie S, Jones N, Smith RL. Metabolic disposition of [14C]-trimethylamine N-oxide in rat: variation with dose and route of administration. Xenobiotica 27: 1187–1197, 1997. doi: 10.1080/004982597239949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyake T, Mizuno T, Mochizuki T, Kimura M, Matsuki S, Irie S, Ieiri I, Maeda K, Kusuhara H. Involvement of Organic Cation Transporters in the Kinetics of Trimethylamine N-oxide. J Pharm Sci 106: 2542–2550, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakhoul GN, Nally JV. Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease. In: CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Nephrology & Hypertension, edited by Lerma EV, Rosner MH, Perazella MA. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neumann T, Ravens U, Heusch G. Characterization of excitation-contraction coupling in conscious dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 37: 456–466, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nowiński A, Ufnal M. Trimethylamine N-oxide: A harmful, protective or diagnostic marker in lifestyle diseases? Nutrition 46: 7–12, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pancaroglu R, Van Petegem F. Calcium channelopathies: structural insights into disorders of the muscle excitation-contraction complex. Annu Rev Genet 52: 373–396, 2018. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120417-031311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park M, Hsu CY, Li Y, Mishra RK, Keane M, Rosas SE, Dries D, Xie D, Chen J, He J, Anderson A, Go AS, Shlipak MG; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group . Associations between kidney function and subclinical cardiac abnormalities in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1725–1734, 2012. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012020145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piacentino V 3rd, Weber CR, Chen X, Weisser-Thomas J, Margulies KB, Bers DM, Houser SR. Cellular basis of abnormal calcium transients of failing human ventricular myocytes. Circ Res 92: 651–658, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000062469.83985.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prokopienko AJ, West RE 3rd, Schrum DP, Stubbs JR, Leblond FA, Pichette V, Nolin TD. Metabolic activation of flavin monooxygenase-mediated trimethylamine-N-oxide formation in experimental kidney disease. Sci Rep 9: 15901, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52032-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Querio G, Antoniotti S, Levi R, Gallo MP. Trimethylamine N-oxide does not impact viability, ros production, and mitochondrial membrane potential of adult rat cardiomyocytes. Int J Mol Sci 20: 20, 2019. doi: 10.3390/ijms20123045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ravens U, Davia K, Davies CH, O’Gara P, Drake-Holland AJ, Hynd JW, Noble MI, Harding SE. Tachycardia-induced failure alters contractile properties of canine ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 32: 613–621, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(96)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Savi M, Bocchi L, Bresciani L, Falco A, Quaini F, Mena P, Brighenti F, Crozier A, Stilli D, Del Rio D. Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)-induced impairment of cardiomyocyte function and the protective role of urolithin B-glucuronide. Molecules 23: 549, 2018. doi: 10.3390/molecules23030549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seldin MM, Meng Y, Qi H, Zhu W, Wang Z, Hazen SL, Lusis AJ, Shih DM. Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes vascular inflammation through signaling of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB. J Am Heart Assoc 5: e002767, 2016. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Senthong V, Li XS, Hudec T, Coughlin J, Wu Y, Levison B, Wang Z, Hazen SL, Tang WH. Plasma trimethylamine N-oxide, a gut microbe-generated phosphatidylcholine metabolite, is associated with atherosclerotic burden. J Am Coll Cardiol 67: 2620–2628, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silswal N, Touchberry CD, Daniel DR, McCarthy DL, Zhang S, Andresen J, Stubbs JR, Wacker MJ. FGF23 directly impairs endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by increasing superoxide levels and reducing nitric oxide bioavailability. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 307: E426–E436, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00264.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh GB, Zhang Y, Boini KM, Koka S. High mobility group box 1 mediates TMAO-induced endothelial dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci 20: 3570, 2019. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stubbs JR, House JA, Ocque AJ, Zhang S, Johnson C, Kimber C, Schmidt K, Gupta A, Wetmore JB, Nolin TD, Spertus JA, Yu AS. Serum trimethylamine-N-oxide is elevated in CKD and correlates with coronary atherosclerosis burden. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 305–313, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014111063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stubbs JR, Stedman MR, Liu S, Long J, Franchetti Y, West RE 3rd, Prokopienko AJ, Mahnken JD, Chertow GM, Nolin TD. Trimethylamine N-oxide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with ESKD receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 261–267, 2019. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06190518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Su Z, Mahmoudinobar F, Dias CL. Effects of trimethylamine-N-oxide on the conformation of peptides and its implications for proteins. Phys Rev Lett 119: 108102, 2017. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.108102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Svensson BG, Akesson B, Nilsson A, Paulsson K. Urinary excretion of methylamines in men with varying intake of fish from the Baltic Sea. J Toxicol Environ Health 41: 411–420, 1994. doi: 10.1080/15287399409531853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang WH, Hazen SL. The contributory role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest 124: 4204–4211, 2014. doi: 10.1172/JCI72331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang WH, Hazen SL. Microbiome, trimethylamine N-oxide, and cardiometabolic disease. Transl Res 179: 108–115, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang WH, Wang Z, Fan Y, Levison B, Hazen JE, Donahue LM, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Prognostic value of elevated levels of intestinal microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide in patients with heart failure: refining the gut hypothesis. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: 1908–1914, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang WH, Wang Z, Kennedy DJ, Wu Y, Buffa JA, Agatisa-Boyle B, Li XS, Levison BS, Hazen SL. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res 116: 448–455, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 368: 1575–1584, 2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tang WH, Wang Z, Shrestha K, Borowski AG, Wu Y, Troughton RW, Klein AL, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota-dependent phosphatidylcholine metabolites, diastolic dysfunction, and adverse clinical outcomes in chronic systolic heart failure. J Card Fail 21: 91–96, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trøseid M, Ueland T, Hov JR, Svardal A, Gregersen I, Dahl CP, Aakhus S, Gude E, Bjørndal B, Halvorsen B, Karlsen TH, Aukrust P, Gullestad L, Berge RK, Yndestad A. Microbiota-dependent metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide is associated with disease severity and survival of patients with chronic heart failure. J Intern Med 277: 717–726, 2015. doi: 10.1111/joim.12328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ufnal M, Nowiński A. Is increased plasma TMAO a compensatory response to hydrostatic and osmotic stress in cardiovascular diseases? Med Hypotheses 130: 109271, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.109271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vincent JL. Understanding cardiac output. Crit Care 12: 174, 2008. doi: 10.1186/cc6975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wacker MJ, Touchberry CD, Silswal N, Brotto L, Elmore CJ, Bonewald LF, Andresen J, Brotto M. Skeletal Muscle, but not Cardiovascular Function, Is Altered in a Mouse Model of Autosomal Recessive Hypophosphatemic Rickets. Front Physiol 7: 173, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM, Wu Y, Schauer P, Smith JD, Allayee H, Tang WH, DiDonato JA, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 472: 57–63, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Z, Tang WH, Buffa JA, Fu X, Britt EB, Koeth RA, Levison BS, Fan Y, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Prognostic value of choline and betaine depends on intestinal microbiota-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. Eur Heart J 35: 904–910, 2014. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wehrens XH, Lehnart SE, Reiken SR, Marks AR. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ Res 94: e61–e70, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125626.33738.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wollenberger A, Will H, Krause EG, Wollenberger A, Will H, Krause EG. Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate, the myocardial cell membrane, and calcium. Recent Adv Stud Cardiac Struct Metab 5: 81–93, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang H, Meng J, Yu H. Trimethylamine N-oxide supplementation abolishes the cardioprotective effects of voluntary exercise in mice fed a Western diet. Front Physiol 8: 944, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States. 2016. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/kidney-disease.

- 77.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic Kidney Disease Basics. Chronic Kidney Disease Initiative, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/basics.html.