Abstract

CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-alpha (CCTα) and CCTβ catalyze the rate-limiting step in phosphatidylcholine (PC) biosynthesis. CCTα is activated by association of its α-helical M-domain with nuclear membranes, which is negatively regulated by phosphorylation of the adjacent P-domain. To understand how phosphorylation regulates CCT activity, we developed phosphosite-specific antibodies for pS319 and pY359+pS362 at the N- and C-termini of the P-domain, respectively. Oleate treatment of cultured cells triggered CCTα translocation to the nuclear envelope (NE) and nuclear lipid droplets (nLDs) and rapid dephosphorylation of pS319. Removal of oleate led to dissociation of CCTα from the NE and increased phosphorylation of S319. Choline depletion of cells also caused CCTα translocation to the NE and S319 dephosphorylation. In contrast, Y359 and S362 were constitutively phosphorylated during oleate addition and removal, and CCTα-pY359+pS362 translocated to the NE and nLDs of oleate-treated cells. Mutagenesis revealed that phosphorylation of S319 is regulated independently of Y359+S362, and that CCTα-S315D+S319D was defective in localization to the NE. We conclude that the P-domain undergoes negative charge polarization due to dephosphorylation of S319 and possibly other proline-directed sites and retention of Y359 and S362 phosphorylation, and that dephosphorylation of S319 and S315 is involved in CCTα recruitment to nuclear membranes.

INTRODUCTION

Phosphatidylcholine (PC), the most abundant glycerophospholipid in mammalian cells, is synthesized de novo by the CDP-choline (Kennedy) pathway, by successive methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and by a salvage pathway involving acylation of lyso-PC. In most tissues, the CDP-choline pathway is the exclusive source of PC, but PE methylation provides a significant contribution to PC synthesis in the liver (Vance and Ridgway, 1988) and for triglyceride storage in adipocytes (Horl et al., 2011). The CDP-choline pathway proceeds by the initial uptake of choline followed by its ATP-dependent phosphorylation by choline kinases. CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-alpha (CCTα) and CCTβ converts phosphocholine to CDP-choline. Choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferases then utilize CDP-choline and diacylglycerol (DAG) to form PC in the endoplasmic reticulum. In most circumstances, CCT catalyzes the rate-limiting and regulated step in PC synthesis (Cornell and Ridgway, 2015).

PCYT1A and PCYT1B encode homodimeric CCTα and CCTβ isoforms, respectively, that are composed of a conserved catalytic domain followed by a membrane-binding amphipathic helix termed the M-domain and a ∼50 residue C-terminal phosphorylation (P)-domain (Figure 1A). The isoforms differ in their cellular location; an N-terminal nuclear localization signal (NLS) in CCTα directs it to the nucleus in most cells (Wang et al., 1995; Aitchison et al., 2015), while CCTβ lacks an NLS and is cytoplasmic (Lykidis et al., 1998). The two isoforms also slightly differ in the sequence of the P-domain (Figure 1A). Both CCTα and β are amphitropic enzymes that are inactive in their soluble forms but are activated by M-domain–mediated translocation to membranes (Cornell and Ridgway, 2015). In vitro, purified CCTα and CCTβ bind selectively to membrane vesicles that are enriched in anionic lipids (e.g., fatty acids and phosphatidic acid) or type II nonbilayer lipids (e.g., phosphatidylethanolamine and DAG; Cornell, 2016). Extensive structural studies of soluble inactive CCTα show that an autoinhibitory helix of the M-domain docks onto the αE helix positioned near the base of the active site and interacts with catalytic residue K122, effectively competing for the substrate CTP (Huang et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014; Ramezanpour et al., 2018). Membrane binding by the M-domain prevents interactions between the autoinhibitory helix and the active site, freeing K122 and allowing the remodeling of αE into a catalytically favorable conformation. M-domain interaction with PC-depleted membranes promotes its folding into a >60-residue amphipathic α-helix (Dunne et al., 1996; Taneva et al., 2003). M-domain folding is promoted by electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions of the N-terminal polybasic region and the C-terminal aromatic-enriched segments, respectively (Arnold and Cornell, 1996; Johnson et al., 2003; Prevost et al., 2018). Engagement of CCT with cell membranes and its consequent activation thus depends on a lipid composition that will effectively stabilize the α-helix conformation of the M-domain.

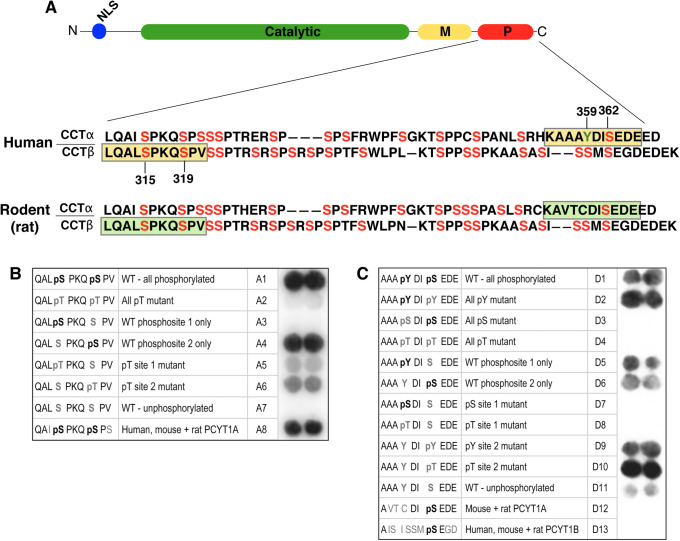

FIGURE 1:

Characterization of phosphosite-specific antibodies against P-domain phosphorylation sites in CCTα and CCTβ. (A) Alignment of human and rat CCTα and CCTβ2 sequences showing the location of phosphorylated serine (red) and tyrosine (green) residues, and the phosphopeptides (yellow boxes) used to generate antibodies against pS315+pS319 and pY359+pS362 phosphosites in human CCTα and CCTβ. Corresponding sequences for rat CCT are shown (green boxes). (B, C) Peptides with the amino acid sequences shown were synthesized on cellulose membranes using the SPOT-synthesis technique and each macroarray was probed with anti–CCTα/β-pS319 (B) or anti–CCTα-pY359+pS362 (C) as described in Materials and Methods.

Membrane binding and α-helix stabilization of the CCTα M-domain is antagonized by phosphorylation of the P-domain (Chong et al., 2014).The CCT P-domain is highly phosphorylated; rat CCTα contains 16 phosphoserine residues (MacDonald and Kent, 1994; Cornell et al., 1995; Wang and Kent, 1995; Bogan et al., 2005), human CCTβ2 has 21 potential serine and threonine phosphosites (Dennis et al., 2011), and phosphoproteome analyses of human liver have identified additional phosphothreonine and phosphotyrosine residues in CCTα and CCTβ (Bian et al., 2014). The P-domain of soluble CCTα is highly phosphorylated relative to the active, membrane-associated enzyme and some residues are dephosphorylated upon membrane binding (Watkins and Kent, 1991; Wang et al., 1993; Houweling et al., 1994). Site-directed mutagenesis of all 16 serine residues to glutamate in rat CCTα caused partial resistance to membrane translocation in response to oleate, yet this phosphomimetic mutant restored PC synthesis and the proliferation of CCTα-deficient CHO cells, showing that the inhibitory effect of P-domain phosphorylation is prevented by a strong lipid activator (Wang and Kent, 1995). In vitro enzymatic analysis of P-domain deletion and S315A mutants of CCTα indicated that phosphorylation caused negative cooperativity for activation by liposomes containing oleate and DAG (Yang and Jackowski, 1995). Dephosphorylation of purified CCTα lowered the anionic lipid requirement for activation by lipid vesicles, an effect that was amplified by the addition of DAG (Arnold et al., 1997). Collectively, these data indicate that dephosphorylation on the P-domain synergizes with alterations in the membrane content of lipid activators to amplify CCTα activity. The structure of CCTα containing the P-domain has not been solved due to its disordered structure, but its proximity to the M-domain indicates that electrostatic interactions between phosphate groups and basic residues in the M-domain could inhibit its insertion into membranes.

The complexity of the P-domain phosphosites has made it difficult to identify relevant kinases and phosphatases. Purified CCTα was phosphorylated in vitro by glycogen synthase kinase-3 and cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) at unidentified sites, whereas casein kinase 2A (CK2A) phosphorylated S362 (Cornell et al., 1995). A later study confirmed that CCTα was phosphorylated in cell extracts by CK2A and CDK1 (Wieprecht et al., 1996). CDK1 could be functionally relevant because the phosphorylation state of nuclear CCTα in macrophages was regulated during the cell cycle (Jackowski, 1994). In fibroblasts, however, the phosphorylation of CCTα through the G1 phase was not correlated with changes in membrane affinity and enzyme activity (Northwood et al., 1999). Recently, mTORC1 was identified as a positive posttranscriptional regulator of CCTα by a mechanism that does not involve direct phosphorylation (Quinn et al., 2017).

Functional analysis of the CCTα and CCTβ P-domain in cells is hampered by the inability to assess phosphorylation of individual sites and correlate this with enzyme translocation and activation at organelle membranes. To address this, phosphosite-specific antibodies were developed for pS319 and pY359+pS362, which are situated at the N- and C-termini of the P-domain, respectively. We report here that phosphorylation of the N- and C-termini regions of the P-domain differs dramatically upon oleate activation of CCTα in cultured cells; pS319 is rapidly dephosphorylated while pY359 and pS362 are constitutively phosphorylated and detected on nuclear membranes and nuclear lipid droplets (nLDs). However, dephosphorylation of sites proximal to the M-domain (S315 and S319) was critical for translocation.

RESULTS

Characterization of antibodies against P-domain phosphosites in CCTα and CCTβ

The P-domains of human and rat CCTα feature 14–16 serine, threonine, and tyrosine phosphorylation sites identified by tryptic mapping (MacDonald and Kent, 1994), analysis of P-domain mutants (Cornell et al., 1995; Wang and Kent, 1995), mass spectrometry of P-domain fragments (Bogan et al., 2005), and high-throughput phosphoproteome analysis (Figure 1A; Hornbeck et al., 2012; Bian et al., 2014). Phosphorylation of the CCTβ P-domain has not been studied as extensively, but many of its serine and threonine residues are conserved with CCTα and several are known to be phosphorylated (Dennis et al., 2011; https://www.phosphosite.org).

To assist in the functional analysis of P-domain phosphorylation sites, phosphosite-specific antibodies were generated against two peptides patterned after four of the most frequently detected and evolutionarily conserved phosphorylated residues in human CCTα and CCTβ; S315+S319 and Y359+S362 (Supplemental Figure S1). Using the SPOT technique of peptide synthesis on cellulose membranes (Frank, 1992), macroarrays of peptides with systematic substitutions at the targeted phosphosites were employed to establish the specificity of these antibodies. The antibody developed against the S315+S319 phosphorylation sites in human CCTβ (Figure 1A) primarily reacted with peptides containing phospho-S319 but not phospho-S315, very weakly detected peptides containing phosphothreonine substitutions, and also immunoreacted with the corresponding phosphopeptides from human, rat, and mouse CCTα (Figure 1B). Antibodies produced against the pY359+pS362 sites in human CCTα (Figure 1A) detected peptides that were singly phosphorylated at either position, but did not react with rodent CCTα or human CCTβ (Figure 1C), as the epitope is poorly conserved. However, while substitution of the S362 position with phosphothreonine and phosphotyrosine produced strong immunoreactivity, pS362 in the absence of pY359 was more weakly detected. In view of the exhibited specificities of these antibodies, they are designated anti-CCTα/β-pS319 and anti-CCTα-pY359+pS362 hereafter.

To validate the specificity of these antibodies toward human and rat CCT isoforms, lysates prepared from COS cells transiently expressing full-length human CCTα, a truncation mutant lacking the M- and P-domains (CCTα1-282), and purified CCTα were immunoblotted (Figure 2A). The CCTα/β-pS319 and CCTα-pY359+pS362 antibodies detected transiently expressed (lane 3) and purified human CCTα (lane 4) but not CCTα1-282 (lane 2). Wild-type (WT) rat CCTα-V5 transiently expressed in HeLa cells was also detected by anti-CCTα/β-pS319, but mutants in which 16 or 7 serine residues (S16-A and 7SP-A, respectively) were mutated to alanine were not (Figure 2B). Rat CCTα-V5 was not detected by the anti-CCTα-pY359+pS362 antibody (Figure 2B), consistent with the poor conservation of these sites in rat CCTα (Figure 1A). Transiently expressed human and rat CCTβ-FLAG were both detected in cell lysates by anti-CCTα/β-pS319 (Figure 2C). However, the CCTα pY359 site is not conserved in human CCTβ (Figure 1A) and was not detected with the CCTα-pY359+pS362 antibody (Figure 2C). To assess the specificity of phosphosite antibodies for endogenous CCT isoforms, we utilized WT human Caco2 cells and Caco2 cells with a CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of PCYT1A (Lee and Ridgway, 2018). Compared to WT Caco2 cells, CCTα knockout cells (KO) lacked expression of a predominant species detected by anti-CCTα/β-pS319 and a 40 kDa species detected by anti-CCTα-pY359+pS362 was also reduced (Supplemental Figure S2A). The residual phosphoproteins detected by anti-CCTα/β-pS319 could correspond to CCTβ, which is expressed in Caco2 cells (Lee and Ridgway, 2018). However, the nonspecific protein detected in Caco2–KO cells by anti-CCTα/β-pY359+pS362 is unlikely to be CCTβ since the antibody does not detect this isoform (Figure 2B).

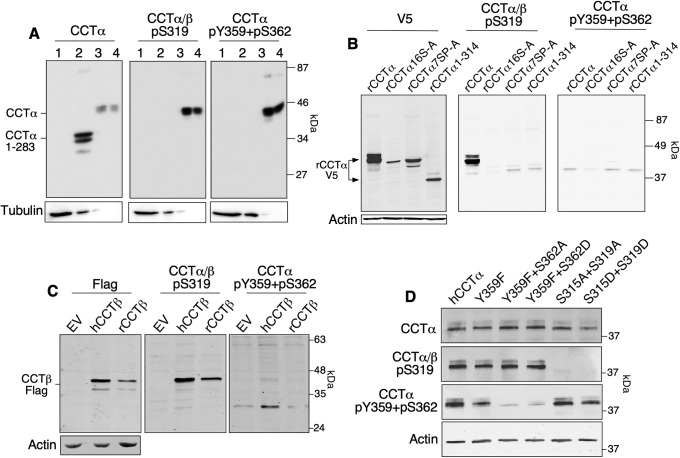

FIGURE 2:

Reactivity of phosphosite-specific antibodies against human and rat CCTα and CCTβ. (A) Lysates prepared from COS cells transiently expressing empty vector (lane 1, 20 μl), hCCTα 1–283 (lane 2, 4 μl), wild-type hCCTα (lane 3, 1 μl), and purified human CCTα (lane 4, 200 ng) were immunoblotted with anti-CCTα, anti–CCTα/β-pS319, anti–CCTα-pY359+pS362, and anti-tubulin antibodies. Differences in expression of hCCTα and hCCTα 1–283 necessitated the loading of different lysate volumes to achieve approximately equal amounts of CCT. (B) HeLa cells transiently expressing V5-tagged rat CCTα, CCTα-16S-A (16 serine residues mutated to alanine), CCTα-7SP-A (seven proline-directed sites mutated to alanine), and CCTα-1-314 (P- and M-domain deleted) were immunoblotted with V5, CCTα/β-pS319, CCTα-pY359+pS362, and actin antibodies. (C) Lysates prepared from CHO-MT58 cells transiently expressing empty vector (EV), human CCTβ-Flag, or rat CCTβ-Flag were immunoblotted with Flag and phosphosite antibodies. (D) Lysates prepared from MT58 CHO cells transiently expressing plasmids encoding untagged human CCTα and the indicated phosphosite mutants were immunoblotted with CCTα and phosphosite antibodies. Immunoblots are representative of results from two to four experiments.

To further establish specificity, we tested the antibodies against site-specific mutants of human CCTα expressed in CHO-MT58 cells that have an unstable temperature-sensitive allele for CCTα (Esko et al., 1981). Compared to WT enzyme, the Y359F mutant showed a 50% reduction in anti–CCTα-pY359+pS362 immunoreactivity, which was almost abolished in the Y359F+S362A and Y359F+S362D double mutants (Figure 2D). As expected, mutating S315 and S319 to aspartate or alanine abolished immunoreactivity. Collectively, these results indicate that the anti-CCTα/β-pS319 antibody reacts well with the phospho-S319 site in both rat and human CCTα and CCTβ, whereas the anti-CCTα-pY359+pS362 detects both Y359 and S362 phosphorylation in human CCTα only.

We investigated the ability of the CCT phosphosite-specific antibodies to detect their targets in mouse tissues (Supplemental Figure S3), where the highest levels of CCTα were in liver, lung > heart, brain > spleen, thymus > kidney, skeletal muscle. In tissues known to have a high percentage of immune cells such as lung, spleen, and thymus, as well as in liver, prominent detection of CCTα/β-pS319 was observed. Consistent with the lack of reactivity with rat CCTα, the CCTα-pY359+pS362 antibody exhibited very weak detection in the mouse tissues.

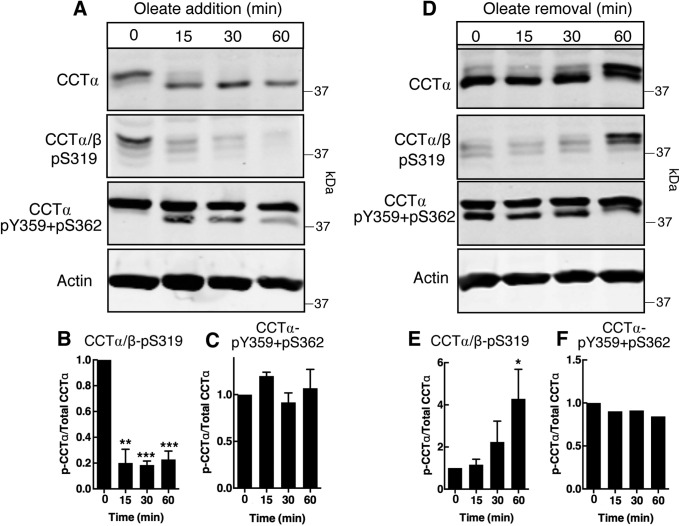

Nuclear membrane association of CCTα induced by oleate loading is linked to dephosphorylation of S319

We next tested whether the antibodies can detect changes in phosphorylation status during CCTα relocation from a soluble to a membrane-bound form in oleate-treated HeLa cells (Pelech et al., 1984; Wang et al., 1993). In preliminary experiments, a 20-min treatment of HeLa cells with an oleate/ bovine serum albumin (BSA) complex caused a marked shift of CCTα and CCTα-pY359+pS362 from the soluble to particulate membrane fraction, whereas the CCTα/β-pS319 signal was only weakly affected (Supplemental Figure S4). Based on confocal immunofluorescence microscopy of control and oleate-treated HeLa cells, the shift of CCTα to the particulate fraction represents translocation from the nucleoplasm to the lamin A/C (LMNA/C)-positive nuclear envelope (NE) and nucleoplasmic reticulum (NR) by 15–30 min (Supplemental Figure S5; Gehrig et al., 2008). Accordingly, a combination of quantitative immunoblotting and fluorescence microscopy was utilized to determine how oleate affects the temporal and compartmental phosphorylation of CCTα. HeLa cells were treated with an oleate/BSA complex for up to 60 min and CCTα phosphorylation was detected with anti–CCTα/β-pS319 (Figure 3, A and B) and anti–CCTα-pY359+pS362 (Figure 3, A and C). Translocation to nuclear membranes after oleate treatment for 15 min coincided with a shift in the electrophoretic mobility of CCTα to a lower mass species, consistent with dephosphorylation (Figure 3A). Accompanying the shift in mass was an 80% reduction in S319 phosphorylation (Figure 3, A and B). By contrast, the pY359+pS362 signal was not affected by oleate, but a lower mass species appeared at 15 min that had a similar mobility to dephosphorylated CCTα (Figure 3, A and C). The removal of oleate from the culture medium resulted in rephosphorylation as indicated by a shift in CCTα protein to a higher mass species and the reappearance of the pS319 signal (Figure 3, D and E). Oleate removal caused the lower mass species pY359/pS362 to shift to the higher mass form that was evident in untreated cells (Figure 3D) but the total pY359/pS362 signal was not affected (Figure 3F).

FIGURE 3:

Oleate treatment of HeLa cells induces reversible dephosphorylation of CCTα S319, but not Y359 or S362. (A–C) HeLa cells were incubated with serum-free DMEM containing 500 µM oleate/BSA for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with CCTα/β-pS319, CCTα-pY359+pS362, CCTα, or actin antibodies. Phosphorylation of S319 (B) and Y359+S362 (C) was quantified relative to total CCTα protein bands. (D–F) HeLa cells were incubated with 300 µM oleate/BSA in serum-free DMEM for 30 min before replacing with serum-free DMEM for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted as described in panel A, and phosphorylation of S319 (E) and Y359+S362 (F) was quantified. Results are the mean and SEM of three experiments. Statistical comparisons were made with 0-h controls.

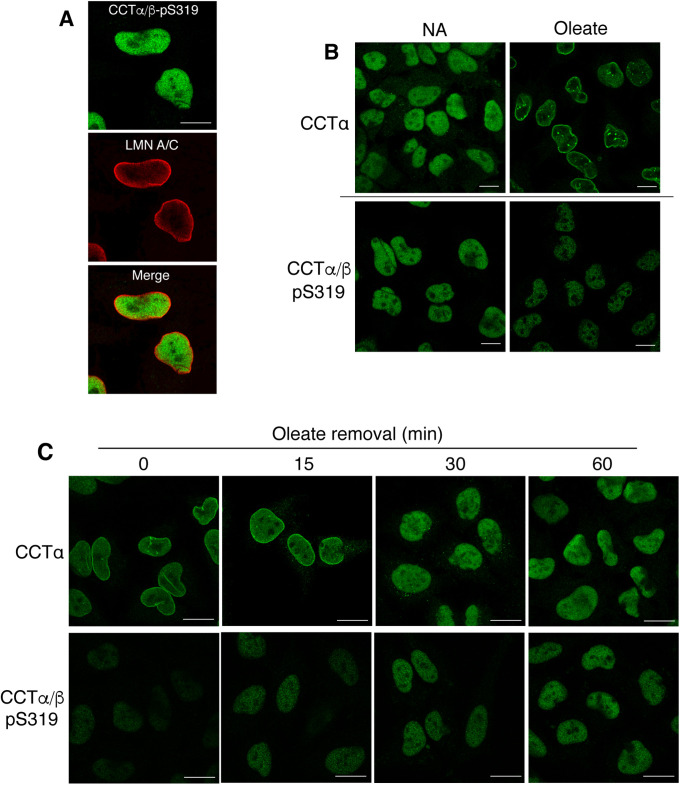

Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis of untreated HeLa cells showed that the CCTα/β-pS319 signal was confined to the nucleoplasm (Figure 4A). Treatment of HeLa cells with oleate for 30 min caused translocation of CCTα to the NE and NR (Figure 4B). In contrast, CCTα phosphorylated on S319 was not detected on nuclear membranes and, consistent with the immunoblotting results (Figure 3), the fluorescence signal in the nucleoplasm was reduced (Figure 4B). The removal of oleate from HeLa cells resulted in dissociation of CCTα from nuclear membranes after 15 min and the appearance of diffuse nucleoplasmic fluorescence (Figure 4C). Coincident with the dissociation of CCTα from nuclear membranes, the immunofluorescence signal for pS319 increased in the nucleoplasm (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4:

CCTα that is translocated to nuclear membranes is reversibly dephosphorylated at S319. (A) HeLa cells were coimmunostained with primary antibodies against CCTα/β-pS319 and LMNA/C, followed by Alexa Fluor–488 and −594 secondary antibodies, respectively. (B) HeLa cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM in the absence (no addition, NA) and presence of 500 µM oleate/BSA for 30 min. Cells were immunostained with primary antibodies against CCTα or anti–CCTα/β-pS319 followed by an Alexa Fluor–488 secondary antibody. (C) HeLa cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM with 300 µM oleate/BSA for 30 min. Oleate-containing media was then replaced with serum-free DMEM and cells were incubated for the indicated times before immunostaining with primary antibodies for CCTα and CCTα/β-pS319 and an Alexa Fluor–488 secondary antibody. All images are 0.8 μm confocal sections. Bar, 10 μm.

To determine whether the observed changes in CCTα phosphosites in oleate-treated HeLa cells was a general phenomenon, CCTα phosphorylation was monitored in nontransformed human skin fibroblasts that were subjected to oleate treatment and removal. Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that CCTα in fibroblasts also translocated to LMNA/C-positive NE and NR after exposure to oleate for 15–30 min (Supplemental Figure S6). Similar to HeLa cells, treatment of fibroblasts with oleate for 15 min shifted CCTα to a lower mass form and S319 phosphorylation was reduced by 90% (Supplemental Figure S7, A and B). A lower mass pY359/pS362 species also appeared that mirrored CCTα protein, but the pY359/pS362 signal relative to total CCTα protein was unchanged (Supplemental Figure S7, A and C). These effects were completely reversed when oleate was removed from cells for 30–60 min (Supplemental Figure S7, D–F). As well, a lack of membrane localization and reduced nucleoplasmic staining was observed using anti–CCTα/β-pS319 in oleate-treated fibroblasts (Supplemental Figure S7G). Oleate removal from fibroblasts also caused CCTα to dissociate from nuclear membranes coincident with a weak increase in pS319 reactivity in the nucleoplasm (Supplemental Figure S7H). Collectively, these data show that S319 is subject to rapid and reversible dephosphorylation in response to oleate-induced translocation of CCTα to the NE and NR. Similarly, oleate treatment of CHO-MT58 cells also caused the progressive dephosphorylation of S319 on transiently expressed cytosolic Flag-tagged human CCTβ (Supplemental Figure S8).

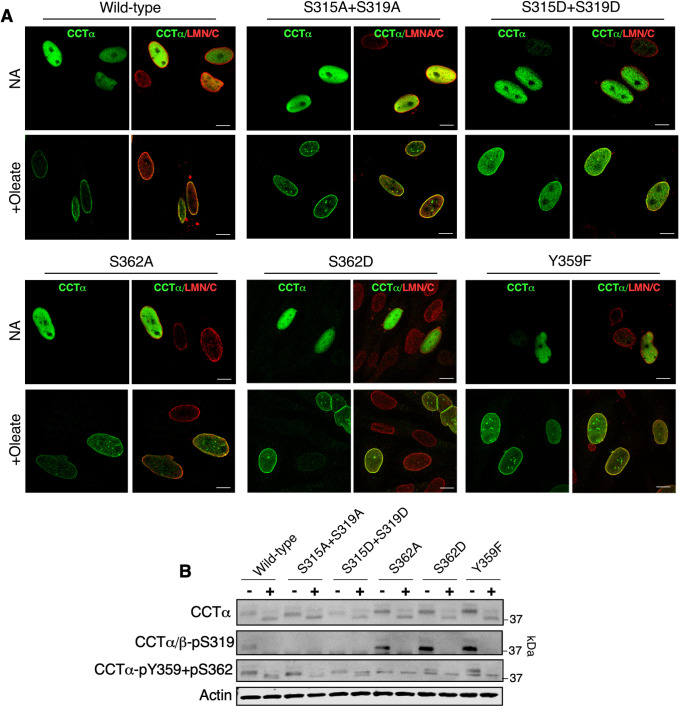

We next introduced alanine, aspartate, or phenylalanine substitutions at the proximal (S315 and S319) or distal (Y359 and S362) sites to determine whether phosphorylation status affected nuclear membrane localization. Transiently expressed WT CCTα and the indicated phosphomutants were localized to the nucleoplasm in untreated CHO-MT58 cells (Figure 5A). A qualitative assessment of CCTα localization in oleate-treated cells indicated strong translocation of the WT enzyme as well as CCTα-S315A+S319A, CCTα-S362A, CCTα-S362D, and CCTα-Y362F to the NE and NR. However, CCTα-S315D+S319D displayed partial translocation from the nucleoplasm to nuclear membranes. Immunoblotting with a CCTα antibody showed that oleate treatment caused WT CCTα and the phosphomutants to shift to lower molecular mass dephosphorylated species (Figure 5B). Similar to WT, the CCTα/β-pS319 antibody reacted with CCTα-S362A, CCTα-S362D, and CCTα-Y359F and the signal was lost upon oleate treatment. In untreated cells, the CCTα-pY359+pS362 antibody detected CCTα with single mutations at those sites as well as CCTα-S315A+S319A and CCTα-S315D+S319D (Figure 5B). Oleate treatment caused the pY359+pS362 signal for WT and CCTα phosphomutants to decrease in mass. These results reveal that dephosphorylation of S315 and S319 is important for nuclear membrane association of CCTα, and that phosphorylation of the S319 and Y359+S362 sites is independently regulated.

FIGURE 5:

CCTα−S315D+S319D is partially defective in localization to nuclear membranes. (A) CHO-MT58 cells transiently expressing wild-type CCTα and the indicated CCTα phosphomutants were cultured at 40°C and treated with 300 µM oleate/BSA for 60 min, fixed, and immunostained with CCTα and LMNA/C primary antibodies followed by AlexaFluor–488 and –594 secondary antibodies, respectively. All images are 0.8-μm confocal sections; bar, 10 μm. (B) Lysates prepared from CHO-MT58 treated as described in A were immunoblotted with CCTα, CCTα/β-pS319, CCTα-pY359+pS362, and actin antibodies. Confocal images and immunoblot are representative of three experiments.

CCTα nuclear membrane localization induced by choline deficiency is linked to S319 dephosphorylation

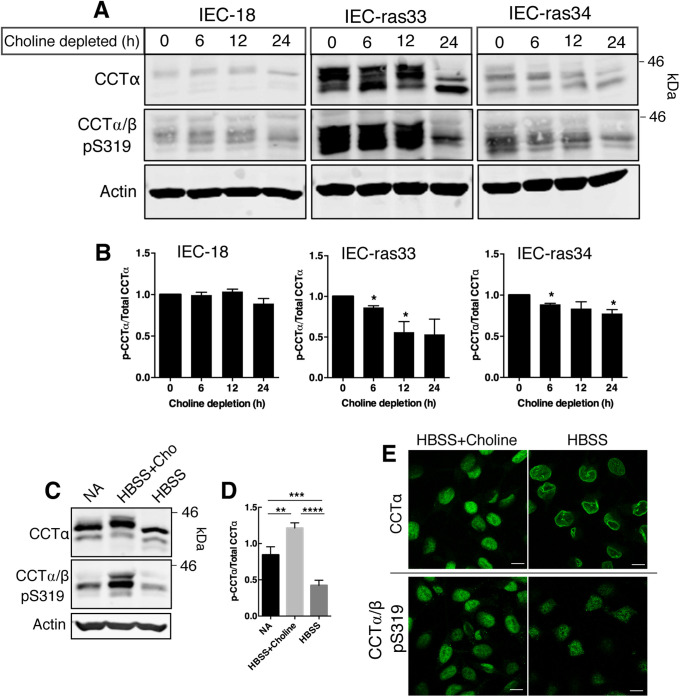

To assess whether the site-selective dephosphorylation of CCTα is specific to oleate treatment or rather reflects membrane translocation per se, we explored the relationship using a different membrane translocation induction model. Choline starvation of cultured cells caused an approximately two-fold decrease in the PC/PE ratio that triggered CCTα membrane translocation (Sleight and Kent, 1983; Jamil et al., 1990; Yao et al., 1990; Weinhold et al.,1994). We utilized nonmalignant rat intestinal epithelial cells (IEC-18) and two H-Ras–transformed IEC-18 clones (IEC-ras33 and IEC-ras34), highly proliferative cells in which CCTα expression is induced (Arsenault et al., 2013), to explore the relationship between S319 phosphorylation and nuclear membrane translocation of CCTα. Choline deprivation of IEC-ras33 and IEC-ras34 for 24 h caused a shift in CCTα to a lower mass species and reduced anti–CCTα/β-pS319 reactivity, indicative of enzyme dephosphorylation (Figure 6, A and B). CCTα/β-pS319 dephosphorylation in IEC-18 was not significant. There was also a significant decrease in pS319 phosphorylation in IEC-ras34 cells that were cultured in Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS) compared with HBSS plus choline or whole medium (Figure 6, C and D). Confocal microscopy showed that CCTα was localized to the nucleoplasm in IEC-ras34 cultured in HBSS plus choline but strongly localized to the NE under choline-free conditions (Figure 6E). In contrast, the nucleoplasmic signal for CCTα-S319 in IEC-ras34 cultured in HBSS plus choline was diminished when cells were cultured in choline-free conditions (Figure 6E). Thus, like the oleate-induced effects, nuclear membrane translocation of CCTα caused by choline deficiency leads to dephosphorylation of S319.

FIGURE 6:

Choline depletion induces dephosphorylation of CCTα S319 in rat intestinal epithelial cells. (A) IEC-18, IEC-ras33, and IEC-ras34 were cultured in choline-free DMEM with 5% dialyzed FBS for up to 24 h. Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted with the primary antibodies against CCTα, CCTα/β-p-S319, and actin. (B) Phosphorylation of S319 was quantified relative to CCTα protein and expressed relative to cells that were not choline depleted (0 h). Results are the mean and SEM of three experiments and statistical comparison was with nondepleted controls (0 h). (C) IEC-ras34 cells were cultured in IEC-MEM (NA, no addition), HBSS with 50 µM choline, or HBSS for 6 h. Whole-cell lysates were resolved by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with CCTα, CCTα/β-p-S319, and actin antibodies. (D) Phosphorylation of S319 was normalized to CCTα protein and expressed relative to control (NA). Results are the mean and SEM of five experiments. (E) IEC-ras34 cultured in HBSS without or with choline for 6 h were immunostained with CCTα or CCTα/β-pS319 primary antibodies followed by an Alexa Fluor–488 secondary antibody. Confocal images are shown (0.8-μm sections); bar, 10 μm.

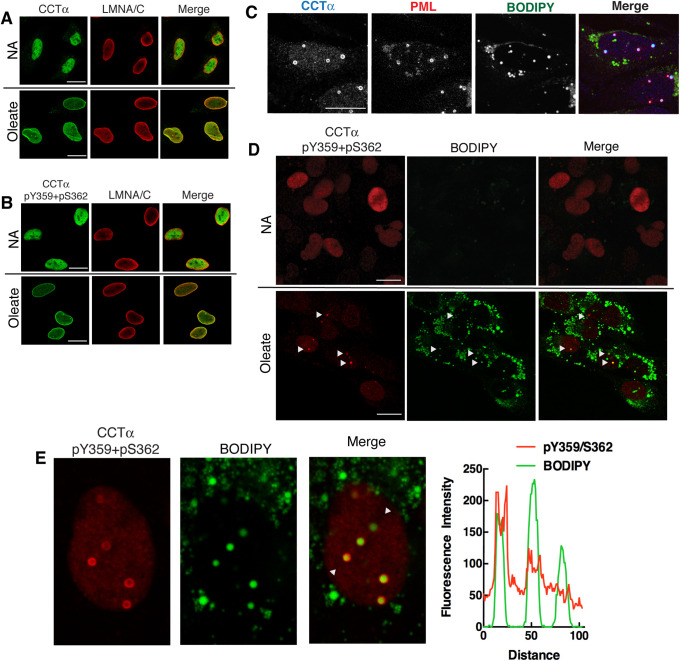

Detection of CCTα-pY359/pS362 on nuclear membranes and lipid droplets

In contrast to S319, phosphorylation of Y359 and S362 was unaffected by oleate addition or removal (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure S7). Using immunofluorescence microscopy, it was evident that both CCTα protein (Figure 7A) and the CCTα-pY359+S362 phosphosite signal (Figure 7B) were confined to the nucleoplasm of untreated HeLa cells, and that both signals relocated to the NE and NR after exposure to oleate indicating that Y359 and S362 remain phosphorylated following translocation to membranes. CCTα also translocates to nLDs following long-term exposure of hepatoma cells to oleate (Ohsaki et al., 2016; Soltysik et al., 2019). To investigate whether CCTα that was phosphorylated at the S319 and Y359+S362 sites was present on nLDs, we utilized oleate-treated U2OS cells that form abundant nDs. As expected, endogenous CCTα in U2OS cells colocalized with the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) protein on the surface of numerous nLDs that were visualized with the lipophilic dye BODIPY493/503 (Figure 7C). CCTα and PML were not present on cytoplasmic LDs. Immunostaining of U2OS cells with anti–CCTα-pY359+pS362 showed a diffuse nucleoplasmic signal in untreated cells (Figure 7D). Oleate treatment for 24 h caused the appearance of numerous CCTα-pY359+pS36 puncta that colocalized with BODIPY-positive nLDs (Figure 7D). Higher magnification images of oleate-treated U2OS cells and cross-sectional analysis of nLDs using RGB line plots revealed that anti–CCTα-pY359+pS362 immunostained the surface of most but not all nLDs (Figure 7E). Immunostaining of nLD by anti–CCTα-pY359+pS362 was specific because the signal on nLD and in the nucleoplasm was absent in Caco2 CCTα−KO cells compared with controls (Supplemental Figure S2B). By contrast, the nucleoplasmic signal for pS319 decreased in oleate-treated U2OS cells and there was no evidence of reactivity with nLDs (Supplemental Figure S9). These results further exemplify the contrasting behaviors of the S319 and Y359/S362 phosphosites following CCTα translocation to the surface of nLDs.

FIGURE 7:

CCTα phosphorylated at Y359 and S362 localizes to nuclear membranes and nuclear lipid droplets in oleate-treated cells. (A, B) HeLa cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM in the absence (NA, no addition) and presence of 300 μM oleate/BSA for 30 min. Cells were immunostained with CCTα (A) or CCTα-pY359+pS362 (B) primary antibodies and an Alexa Fluor–488 secondary antibody in combination with primary LMNA/C and an Alexa Fluor–594 secondary antibodies. (C) U2OS cells treated with 300 µM oleate/BSA for 24 h were probed with primary antibodies to detect CCT and promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies, followed by Alexa Fluor–637 and Alexa Fluor–488 secondary antibodies. BODIPY493/503 was used to visualize nLDs. (D) U2OS cells cultured without (NA) or with oleate for 24 h were incubated with anti–CCTα-pY359+pS362 (with Alexa Fluor–594 secondary antibody) and BODIPY493/503. Arrows indicate the position of nuclear LDs positive for CCTα-pY359+pS362. (E) Enlarged nucleus from the panel E data set with arrows indicating the region selected for a RGB line plot showing colocalization of CCTα-pY359+pS362 and BODIPY-positive nLDs. All images are 0.8-μm confocal sections; bar, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

Physical properties of PC-deficient membranes, such as increased charge and hydrophobic packing voids, drive the attraction and folding of the CCT amphipathic helical M-domain (Cornell, 2016). In many cell types and under different stimuli, the translocation of CCTα from a soluble compartment (e.g., the nucleoplasm) to membranes was associated with dephosphorylation. The phosphorylation sites that are affected by membrane association are restricted to the P-domain and, due to their proximity to the M-domain, could affect CCTα and β membrane association and activity. However, determining the functionality of the P-domain has been problematic owing to the number and diversity of phosphosites.

In this study, we have developed antibodies to track the phosphorylation status of sites proximal (pS319) and distal (pY359 and pS362) to the M-domain in several cell types upon CCTα membrane translocation induced by oleate, which creates both increased negative charge and surface packing strain due to its small headgroup. Oleate supplementation also promotes the formation of cytoplasmic and nuclear LDs, which are covered with a phospholipid monolayer and are sites for CCT binding via the M-domain (Krahmer et al., 2011; Prevost et al., 2018). Our new data showed that M-domain proximal proline-directed S319 is dephosphorylated upon CCTα membrane translocation to the NE, NR, and nLDs, but the distal C-terminal sites remain phosphorylated. Because the pY359+pS362 antibody detects total phosphorylation of both sites, we cannot be certain that its reactivity reflects preservation of singly or doubly phosphorylated sites. The preferential dephosphorylation of M-domain proximal S319 and likely S315 enhances membrane association, while the C-terminus has constitutive negative charge that is compatible with the function of both the soluble and membrane-bound forms.

CCTα and CCTβ contain 7 and 8 serine–proline (S–P) sites, respectively, clustered toward the C-terminus of the P-domain (Figure 1A). Dephosphorylation of S319 occurred in the nucleoplasm or very rapidly following translocation CCTα to nuclear membranes as a result of decreased kinase and/or increased phosphatase activities and thus was not detected on the NE or NR. Similarly, phosphorylation of S319 could occur during or after localization to the nucleoplasm as CCTα becomes a more favorable substrate for kinases. Kinase and phosphatase activity toward CCTα could be driven by compartmentalization. In addition, the lipids that promote the membrane translocation of CCTα could also be direct activators and inhibitors of nuclear phosphatase and kinase activities, respectively. A potential caveat when interpreting experiments with the CCTα/β-pS319 antibody is that it also detects phosphorylated CCTβ. Because the antibody detected CCTα S319 phosphorylation in the nucleus of HeLa cells and fibroblasts and CCTβ is a cytoplasmic enzyme, we conclude that cross-reactivity of the CCTα/β-pS319 antibody is not a concern.

Our results support the hypothesis that phosphorylation of sites proximal to the M-domain modulate the strength of membrane binding due to electrostatic repulsion (Arnold et al., 1997; Chong et al., 2014). Chong et al. (2014) showed that the negative charge on the CCTα P-domain antagonizes the electrostatic attraction of the positively charged M-domain for anionic vesicles, making the binding more reliant on hydrophobic packing gaps in the membrane induced by increased curvature. In that study, all 16 serine residues were either unphosphorylated or changed to glutamate residues to produce a phosphomimetic. Negative charge nearer the M-domain (i.e., pS315 and pS319) has a larger impact on membrane affinity of the M-domain because recombinant CCTα S315A had an increased affinity for lipid vesicles (Yang and Jackowski, 1995). Our mutagenesis analysis of S315 and S319 indicates that phosphorylation or phosphomimicry of these sites negatively regulates CCTα translocation to nuclear membranes in CHO-MT58 cells treated with oleate. Because CCTα-S315D+S319D was partially localized to the NE and NR, other S–P sites must also be dephosphorylated upon membrane binding to fully eliminate the electrostatic repulsion. Although P-domains of many metazoans contain an abundance of S–P sites, in plants, protists, and fungi these sites are often replaced with D/E-rich motifs, indicating that the negative charge on the P-domain is the key feature linked to phosphorylation.

The C-terminal phosphosite in human CCTα, but not rodent CCTα or CCTβ isoforms, was detected with the CCTα-pY359+pS362 antibody. The very C-terminus of CCTα has a cluster of six aspartate and glutamate residues in addition to phospho-Y359 and -S362, which imparts a constitutive negative charge, not unlike D/E-rich motifs in other metazoans. This contrasts the remainder of the P-domain in which the negative charge density is regulated by reversible phosphorylation. Phosphomutants of Y359 and S362 did not affect membrane translocation nor did they affect S319 phosphorylation, which supports an independent function for the terminal acidic region. This could involve electrostatic interactions with the M-domain in the CCT soluble form or with other proteins.

CCTα interaction with nLDs was also linked to dephosphorylation of S319 and phosphorylation of Y359/S362. Like their cytoplasmic counterparts, nLDs have a neutral lipid core and surface phospholipids, and dynamically expand and contract depending on fatty acid availability (Layerenza et al., 2013; Lagrutta et al., 2017). In hepatocytes, nLDs arise from lipid droplet precursors of lipoproteins in the ER lumen that are released into the nucleoplasm (Soltysik et al., 2019) and assembled on the inner NE by a poorly understood mechanism that involves PML-II (Ohsaki et al., 2016). CCTα association with the surface of nLDs could be part of a feedback mechanism that increases CDP-choline and cytoplasmic PC synthesis to relieve ER stress and increase cytoplasmic triacylglycerol storage (Soltysik et al., 2019). In silico and in vitro studies have indicated that docking and folding of the CCTα M-domain on LD monolayers is primarily driven by the interaction of bulky hydrophobic residues with surface packing defects (Prevost et al., 2018). Other amphipathic helix interactions with LDs in cells, for example, Pln4, rely on both electrostatics and hydrophobicity (Copic et al., 2018). Dephosphorylation of S319 accompanied CCTα association with nLDs so electrostatic attractions may also contribute. Dephosphorylation of the P-domain may increase the affinity and competitiveness of CCTα for binding to nLD (Kory et al., 2016). For example, changes in CCTα phosphorylation may affect its ability to compete with perilipin 3 for binding to nLDs and control the rate of PC synthesis (Soltysik et al., 2019).

This study is the first to uncover striking differences in the phosphorylation status of P-domain residues in response to CCTα activation. S319 is one of seven proline-directed kinase sites in human CCTα that could undergo coordinated phosphorylation to negatively regulate M-domain association with nuclear membranes and nLDs (Figure 8). In this model, electrostatic interactions between basic residues in the disordered M-domain and phosphate groups in the P-domain would stabilize the soluble form of CCT by dampening the electrostatic attraction of the M-domain for the membrane surface. Numerous and variable weak polar interactions can integrate to create tight-binding interactions (Borgia et al., 2018). The potential for this mode of contact between the M- and P-domains implies that the overall negative charge density of domain P is the important regulatory variable. Dephosphorylation of S–P sites, notably S315 and S319, would disrupt inhibitory contacts with the M-domain that in combination with an attractive signal from the membrane surface (e.g., PC depletion) would drive strong membrane partitioning. The data thus far indicate that the constitutive phosphosites distal to the M-domain do not take part in shifting the membrane-binding equilibrium. However, their negative charge might prime P-domain phosphorylation and membrane disengagement of CCT when PC content is reestablished.

FIGURE 8:

Model for phosphoregulation of CCTα. CCTα is inhibited by the autoinhibitory helix (yellow) near the end of the M-domain, which interacts with the αE helix (blue) to block substrate access to the active site. Electrostatic interactions between basic residues in the disordered M-domain and phosphate groups in the P-domain (red) would prevent helical folding of the M-domain. Membranes depleted in PC or enriched in anionic lipids would promote M-domain helical folding, which is enhanced by loss of electrostatic interactions due to dephosphorylation of P-domain S–P sites; notably, S315 and S319.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were raised against synthetic phosphopeptides patterned after human CCTα and CCTβ phosphosites (Figure 1A) and affinity-purified (PCYT1B-pS315+pS319 [AB-PN546] and PCYT1A-pY359+pS362 [AB-PN548]; Kinexus, Vancouver, BC). The immunizing phosphopeptides were produced by solid-phase synthesis on a Multipep peptide synthesizer and purified by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Purity was assessed by analytical HPLC and the amino acid identity confirmed by mass spectrometry analysis. Each phosphopeptide was coupled to KLH and subcutaneously injected into New Zealand White rabbits every 4 wk for 4 mo. The sera from these animals were applied onto agarose columns to which each immunogen phosphopeptide was separately thio-linked. Antibodies were eluted from the columns with 0.1 M glycine (pH 2.5) and immediately neutralized to pH 7.0 with saturated Tris base.

The rabbit CCTα polyclonal antibody raised against a peptide in the P-domain (PSPSFRWPFSGKTSP) was previously described (Morton et al., 2013). The phosphosite-specific extracellular-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2)-pT185+pY187 antibody was from Kinexus (Vancouver, BC). Flag monoclonal (M2) and β actin monoclonal (AC-15) antibodies were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, ON). LMNA/C monoclonal antibody (4C11) was from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The tubulin monoclonal antibody was from Applied Biological Materials (Richmond, BC, Canada). Alexa Fluor–488 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor–594 goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies were bought from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit and IRDye 680LT goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies, and Odyssey Blocking Buffer were purchased from LI-COR (Lincoln, NE). Donkey horseradish peroxidase–coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibody was obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA).

SPOT peptide macroarrays

Peptide macroarrays were manufactured directly on cellulose membranes by SPOT synthesis as described by Hilpert et al. (2007). The estimated amount of peptide per spot was 10 µg and each peptide was synthesized in duplicate. Following blocking with 5% (wt/vol) sucrose, 4% (wt/vol) BSA in 50 mM Tris base, pH 8.0, 27 mM KCl, 136 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20), SPOT macroarrays were probed with 0.5 μg/ml of a primary polyclonal rabbit antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C, and subsequently incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 20 ng/ml horseradish peroxidase–coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibody in blocking buffer. Detection was carried out by enhanced chemiluminescence after initial incubation for 10 s with scanning every 15 s on a Fluor-S Max Multi-Imager (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Plasmids

pCMV-hCCTα was prepared by digesting pAX-CCTα with Mlu1 and BamH1 and subcloning into pCMV3. Construction of the rat CCTα expression vector pcDNA-rCCTα-V5 was previously described (Lagace and Ridgway, 2005). pCMV-rCCTβ-Flag (NM173151, rat CCTβ2 isoform; Jackowski et al., 2004) and pCMV-hCCTβ-Flag (NM004845, human CCTβ2 isoform; Lykidis et al., 1999) were purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD). Site-directed mutagenesis of S315, S319, Y359, and S362 in pCMV-hCCTα used PCR extension of overlapping primers and Dpn1 digestion. Mutations were confirmed by sequencing.

Cell culture and transfections

Human skin fibroblasts, HeLa, U2OS, and Caco2 and Caco2-CCTα KO (Lee and Ridgway, 2018) cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. IEC-18, IEC-ras33, and IEC-ras34 were cultured in α-MEM containing 5% FBS, glucose (3.6 g/l), insulin (12.7 μg/ml), and glutamine (2.9 mg/ml). CHO-MT58 cells were cultured at 33°C in DMEM containing 5% fetal calf serum and proline (34 μg/ml). For transfections, cells were transfected with plasmids at a 2:1 (vol/wt) ratio of Lipofectamine 2000 to DNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific). The media on transfected cells was replaced after 24 h.

A stock solution of oleate/BSA (6.6:1, mol:mol, 10 mM oleate) was prepared as previously described and stored at −20°C (Goldstein et al., 1983). Cultured cells were treated with 300 µM or 500 µM oleate/BSA in serum-free DMEM as described in the figure legends. For the choline depletion and supplementation studies, IEC and IEC-ras were cultured in choline-replete DMEM with 5% FBS (control) for 24 h or choline-free DMEM with 5% dialyzed FBS for 6–24 h, or cultured in HBSS with or without 50 µM choline for 6 h.

Immunoblotting

Following treatments, cells were rinsed once with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed on the dish in 1X SDS–PAGE sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol). Lysates were sonicated for 5–7 s, heated to 90°C for 3 min, resolved by SDS–PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were incubated in blocking buffer (1:5 dilution of Licor Odyssey blocking buffer in is Tris-buffered saline-Tween [TBS-Tween; 20 mM Tris base, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20]) containing primary CCTα (1:500), CCTα-pY359+pS362 (1 µg/ml), or CCTβ-pS315+pS319 (1 µg/ml) antibodies and the actin monoclonal followed by IRDye 800CW and 680LT secondary antibodies. Filters were scanned using a Licor Odyssey imaging system and quantified using associated software (v3.0).

Mouse tissue lysates were produced by direct sonication of harvested organs in 1X SDS–PAGE sample buffer, resolved by SDS–PAGE, and immunoblotted with phosphosite-specific antibodies (2 µg/ml) in blocking buffer (2.5% BSA in TBS-Tween) overnight at 4°C. Proteins were detected with a horseradish peroxidase–coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibody using the ECL method.

Lysates from COS-1 cells expressing WT and mutant human CCT were prepared and WT human CCTα was purified as described (Cornell et al., 2019). Volumes were loaded that would provide equivalent amounts of CCTα. After transfer and blocking, the PVDF filters were incubated with the anti-phosphosite antibodies or with an antibody against residues 256–288 of the M-domain (Johnson et al., 1997).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells cultured on 1-mm glass coverslips were fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS at 4°C for 15 min. Coverslips were blocked overnight at 4°C in PBS containing 1% (wt/vol) BSA (PBS/BSA). CCTα (1:1000 dilution), CCTα-pS315+pS319 (1–2 µg/ml), CCTα-pY359+pS362 (1 µg/ml), and LMNA/C (1:250–1:500 dilution) antibodies in PBS/BSA were incubated with coverslips on parafilm in a humidity chamber for 4 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. After incubation with Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibodies, coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich) and cells were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with a 100× Plan APOCHROMAT 100×/1.40 numerical aperture oil immersion objective and argon 488/HeNe 548 lasers. The confocal images shown in figures were representative of results from three or four independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of data was determined from three or more independent experiments using a two-tailed Student’s t test analysis (GraphPad Prism 6.0). Error bars represent the SE of the mean (SEM) and significance is reported for p < 0.05 (*), 0.01 (**), 0.001 (***), and 0.001 (****).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Douglas for excellent technical assistance. This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant no.162390). M.J.M. was supported by a studentship from the Beatrice Hunter Cancer Research Institute. L.Y. was supported by a 4-year fellowship award from the University of British Columbia and Kinexus Bioinformatics. This publication is dedicated to our mentors Dennis Vance and Jean Vance.

Abbreviations used:

- CCTα and PCYT1A

CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-alpha

- CCTβ and PCYT1B

CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-beta

- CDK1

cyclin-dependent kinase-1

- CK2A

casein kinase 2A

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- ERK

extracellular-regulated kinase

- HBSS

HEPES-buffered salt solution

- LMNA/C

lamin A/C

- NE

nuclear envelope

- nLD

nuclear lipid droplets

- NLS

nuclear localization signal

- NR

nucleoplasmic reticulum

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PML

promyelocytic leukemia

- S-P

serine-proline

- TBS-Tween

Tris-buffered saline-Tween.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E20-01-0014) on March 11, 2020.

REFERENCES

- Aitchison AJ, Arsenault DJ, Ridgway ND. (2015). Nuclear-localized CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α regulates phosphatidylcholine synthesis required for lipid droplet biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell , 2927–2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold RS, Cornell RB. (1996). Lipid regulation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase: electrostatic, hydrophobic, and synergistic interactions of anionic phospholipids and diacylglycerol. Biochemistry , 9917–9924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold RS, DePaoli-Roach AA, Cornell RB. (1997). Binding of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase to lipid vesicles: diacylglycerol and enzyme dephosphorylation increase the affinity for negatively charged membranes. Biochemistry , 6149–6156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault DJ, Yoo BH, Rosen KV, Ridgway ND. (2013). ras-Induced up-regulation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α contributes to malignant transformation of intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem , 633–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Y, Song C, Cheng K, Dong M, Wang F, Huang J, Sun D, Wang L, Ye M, Zou H. (2014). An enzyme assisted RP-RPLC approach for in-depth analysis of human liver phosphoproteome. J Proteomics , 253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan MJ, Agnes GR, Pio F, Cornell RB. (2005). Interdomain and membrane interactions of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase revealed via limited proteolysis and mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem , 19613–19624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgia A, Borgia MB, Bugge K, Kissling VM, Heidarsson PO, Fernandes CB, Sottini A, Soranno A, Buholzer KJ, Nettels D, et al. (2018). Extreme disorder in an ultrahigh-affinity protein complex. Nature , 61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SS, Taneva SG, Lee JM, Cornell RB. (2014). The curvature sensitivity of a membrane-binding amphipathic helix can be modulated by the charge on a flanking region. Biochemistry , 450–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copic A, Antoine-Bally S, Gimenez-Andres M, La Torre Garay C, Antonny B, Manni MM, Pagnotta S, Guihot J, Jackson CL. (2018). A giant amphipathic helix from a perilipin that is adapted for coating lipid droplets. Nat Commun , 1332–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell RB. (2016). Membrane lipid compositional sensing by the inducible amphipathic helix of CCT. Biochim Biophys Acta , 847–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell RB, Kalmar GB, Kay RJ, Johnson MA, Sanghera JS, Pelech SL. (1995). Functions of the C-terminal domain of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. Effects of C-terminal deletions on enzyme activity, intracellular localization and phosphorylation potential. Biochem J , 699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell RB, Ridgway ND. (2015). CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase: function, regulation, and structure of an amphitropic enzyme required for membrane biogenesis. Prog Lipid Res , 147–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell RB, Taneva SG, Dennis MK, Tse R, Dhillon RK, Lee J. (2019). Disease-linked mutations in the phosphatidylcholine regulatory enzyme CCTα impair enzymatic activity and fold stability. J Biol Chem , 1490–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis MK, Taneva SG, Cornell RB. (2011). The intrinsically disordered nuclear localization signal and phosphorylation segments distinguish the membrane affinity of two cytidylyltransferase isoforms. J Biol Chem , 12349–12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne SJ, Cornell RB, Johnson JE, Glover NR, Tracey AS. (1996). Structure of the membrane binding domain of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. Biochemistry , 11975–11984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esko JD, Wermuth MM, Raetz CR. (1981). Thermolabile CDP-choline synthetase in an animal cell mutant defective in lecithin formation. J Biol Chem , 7388–7393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank R. (1992). Spot-synthesis—an easy technique for the positionally addressable, parallel chemical synthesis on a membrane support. Tetrahedron , 9217–9232. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrig K, Cornell RB, Ridgway ND. (2008). Expansion of the nucleoplasmic reticulum requires the coordinated activity of lamins and CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α. Mol Biol Cell , 237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, Basu SK, Brown MS. (1983). Receptor mediated endocytosis of low-density lipoprotein in cultured cells. Methods Enzymol , 241–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert K, Winkler DFH, Hancock REW. (2007). Peptide arrays on cellulose support: SPOT synthesis, a time and cost efficient method for synthesis of large numbers of peptides in a parallel and addressable fashion. Nat Protoc , 1333–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horl G, Wagner A, Cole LK, Malli R, Reicher H, Kotzbeck P, Kofeler H, Hofler G, Frank S, Bogner-Strauss JG, et al. (2011). Sequential synthesis and methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine promote lipid droplet biosynthesis and stability in tissue culture and in vivo. J Biol Chem , 17338–17350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbeck PV, Kornhauser JM, Tkachev S, Zhang B, Skrzypek E, Murray B, Latham V, Sullivan M. (2012). PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res , D261–D270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houweling M, Jamil H, Hatch GM, Vance DE. (1994). Dephosphorylation of CTP-phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase is not required for binding to membranes. J Biol Chem , 7544–7551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HK, Taneva SG, Lee J, Silva LP, Schriemer DC, Cornell RB. (2013). The membrane-binding domain of an amphitropic enzyme suppresses catalysis by contact with an amphipathic helix flanking its active site. J Mol Biol , 1546–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski S. (1994). Coordination of membrane phospholipid synthesis with the cell cycle. J Biol Chem , 3858–3867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski S, Rehg JE, Zhang YM, Wang J, Miller K, Jackson P, Karim MA. (2004). Disruption of CCTβ2 expression leads to gonadal dysfunction. Mol Cell Biol , 4720–4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil H, Yao ZM, Vance DE. (1990). Feedback regulation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase translocation between cytosol and endoplasmic reticulum by phosphatidylcholine. J Biol Chem , 4332–4339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Aebersold R, Cornell RB. (1997). An amphipathic α-helix is the principle membrane-embedded region of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. Identification of the 3-(trifluoromethyl)-3-(m-[125I]iodophenyl) diazirine photolabeled domain. Biochim Biophys Acta , 273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Xie M, Singh LM, Edge R, Cornell RB. (2003). Both acidic and basic amino acids in an amphitropic enzyme, CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase, dictate its selectivity for anionic membranes. J Biol Chem , 514–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kory N, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. (2016). Targeting fat: mechanisms of protein localization to lipid droplets. Trends Cell Biol , 535–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahmer N, Guo Y, Wilfling F, Hilger M, Lingrell S, Heger K, Newman HW, Schmidt-Supprian M, Vance DE, Mann M, et al. (2011). Phosphatidylcholine synthesis for lipid droplet expansion is mediated by localized activation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. Cell Metab , 504–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagace TA, Ridgway ND. (2005). The rate-limiting enzyme in phosphatidylcholine synthesis regulates proliferation of the nucleoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biol Cell , 1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagrutta LC, Montero-Villegas S, Layerenza JP, Sisti MS, Garcia de Bravo MM, Ves-Losada A. (2017). Reversible nuclear-lipid-droplet morphology induced by oleic acid: a link to cellular-lipid metabolism. PLoS One , e0170608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layerenza JP, Gonzalez P, Garcia de Bravo MM, Polo MP, Sisti MS, Ves-Losada A. (2013). Nuclear lipid droplets: a novel nuclear domain. Biochim Biophys Acta , 327–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Ridgway ND. (2018). Phosphatidylcholine synthesis regulates triglyceride storage and chylomicron secretion by Caco2 cells. J Lipid Res , 1940–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Taneva SG, Holland BW, Tieleman DP, Cornell RB. (2014). Structural basis for autoinhibition of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT), the regulatory enzyme in phosphatidylcholine synthesis, by its membrane-binding amphipathic helix. J Biol Chem , 1742–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykidis A, Baburina I, Jackowski S. (1999). Distribution of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT) isoforms. Identification of a new CCTβ splice variant. J Biol Chem , 26992–27001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykidis A, Murti KG, Jackowski S. (1998). Cloning and characterization of a second human CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J Biol Chem , 14022–14029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JI, Kent C. (1994). Identification of phosphorylation sites in rat liver CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J Biol Chem , 10529–10537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton CC, Aitchison AJ, Gehrig K, Ridgway ND. (2013). A mechanism for suppression of the CDP-choline pathway during apoptosis. J Lipid Res , 3373–3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northwood IC, Tong AH, Crawford B, Drobnies AE, Cornell RB. (1999). Shuttling of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase between the nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum accompanies the wave of phosphatidylcholine synthesis during the G(0) → G(1) transition. J Biol Chem , 26240–26248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsaki Y, Kawai T, Yoshikawa Y, Cheng J, Jokitalo E, Fujimoto T. (2016). PML isoform II plays a critical role in nuclear lipid droplet formation. J Cell Biol , 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelech SL, Cook HW, Paddon HB, Vance DE. (1984). Membrane-bound CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase regulates the rate of phosphatidylcholine synthesis in HeLa cells treated with unsaturated fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta , 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevost C, Sharp ME, Kory N, Lin Q, Voth GA, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. (2018). Mechanism and determinants of amphipathic helix-containing protein targeting to lipid droplets. Dev Cell , 73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn WJ, III, Wan M, Shewale SV, Gelfer R, Rader DJ, Birnbaum MJ, Titchenell PM. (2017). mTORC1 stimulates phosphatidylcholine synthesis to promote triglyceride secretion. J Clin Invest , 4207–4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramezanpour M, Lee J, Taneva SG, Tieleman DP, Cornell RB. (2018). An auto-inhibitory helix in CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase hi-jacks the catalytic residue and constrains a pliable, domain-bridging helix pair. J Biol Chem , 7070–7083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleight R, Kent C. (1983). Regulation of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in mammalian cells. III. Effects of alterations in the phospholipid compositions of Chinese hamster ovary and LM cells on the activity and distribution of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J Biol Chem , 836–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltysik K, Ohsaki Y, Tatematsu T, Cheng J, Fujimoto T. (2019). Nuclear lipid droplets derive from a lipoprotein precursor and regulate phosphatidylcholine synthesis. Nat Commun , 473–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneva S, Johnson JE, Cornell RB. (2003). Lipid-induced conformational switch in the membrane binding domain of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase: a circular dichroism study. Biochemistry , 11768–11776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE, Ridgway ND. (1988). The methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine. Prog Lipid Res , 61–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kent C. (1995). Effects of altered phosphorylation sites on the properties of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J Biol Chem , 17843–17849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, MacDonald JI, Kent C. (1993). Regulation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase in HeLa cells. Effect of oleate on phosphorylation and intracellular localization. J Biol Chem , 5512–5518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, MacDonald JI, Kent C. (1995). Identification of the nuclear localization signal of rat liver CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J Biol Chem , 354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins JD, Kent C. (1991). Regulation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase activity and subcellular location by phosphorylation in Chinese hamster ovary cells. The effect of phospholipase C treatment. J Biol Chem , 21113–21117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhold PA, Charles L, Feldman DA. (1994). Regulation of CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase in HepG2 cells: effect of choline depletion on phosphorylation, translocation and phosphatidylcholine levels. Biochim Biophys Acta , 335–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieprecht M, Wieder T, Paul C, Geilen CC, Orfanos CE. (1996). Evidence for phosphorylation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase by multiple proline-directed protein kinases. J Biol Chem , 9955–9961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao ZM, Jamil H, Vance DE. (1990). Choline deficiency causes translocation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase from cytosol to endoplasmic reticulum in rat liver. J Biol Chem , 4326–4331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Jackowski S. (1995). Lipid activation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase is regulated by the phosphorylated carboxyl-terminal domain. J Biol Chem , 16503–16506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.