Abstract

Novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2: SARS-CoV-2) has a high homology with other cousin of coronaviruses such as SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS). After outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 in China, it has spread so fast around the world. The main complication of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is respiratory failure, but several patients have also been admitted to the hospital with neurological symptoms. Direct invasion, hematogenic rout, retrograde and anterograde transport along peripheral nerves are considered as main neuroinvasion mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. In the present study, we describe the possible routes for entering of SARS-CoV-2 into the nervous system. Then, the neurological manifestations of the SARS-CoV-2 infection in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) are reviewed. Furthermore, the neuropathology of the virus and its impacts on other neurological disorders are discussed.

Keywords: Novel coronavirus, Nervous system, Neurological symptoms, Neuroinvasion

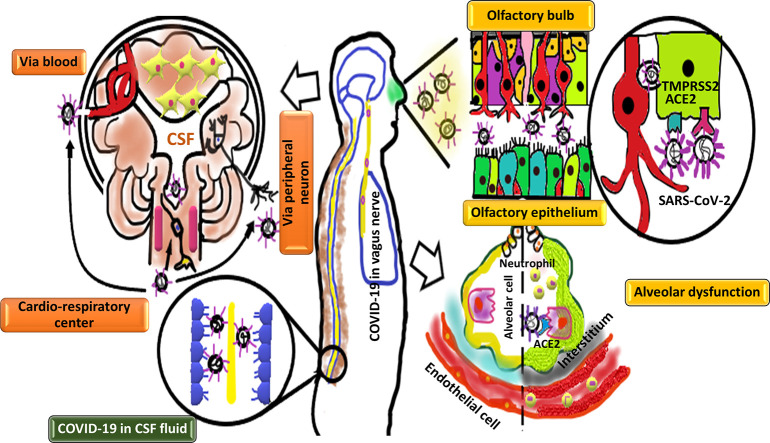

Graphical abstract

Different routes for entering of SARS-CoV-2 to the nervous system.

1) Neuronal pathway: SARS-CoV-2 may enter to the nervous tissue through retrograde and anterograde transport along peripheral nerves. The SARS-CoV-2 may infect the olfactory bulb through TMPRSS2 and ACE2 receptors. Moreover, the virus may transfer through extracellular vesicle (EVs) in the olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs) which is independent to the ACE2 receptors. In addition to olfactory nerve, the virus can transport via trigeminal and vagus nerves. Interestingly, viral infection of cardio-respiratory center in the brain stem may relate with the respiratory failure. (2) Blood circulation pathway: the virus may use blood stream to enter the central nervous system (CNS). The virus (either in blood stream or cerebrospinal fluid) infects epithelial cells of the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB) in the choroid plexus (CP) of the brain's ventricles.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a pandemic crisis with the ability to kills millions of people. Novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2: SARS-CoV-2) was first detected in China on 12 December 2019 and has rapidly spread among rest of the world [1]. The SARS-CoV-2 belongs to Beta-coronavirus family, ranging from 26 to 32 kilobases in length. The RNA virus is enveloped with a positive sense single-stranded RNA genome [2]. There is a closest linkage between two SARS-like coronaviruses from bat. Four structural proteins are considered for the virus as (E) the envelope protein, (M) the membrane protein, (S) the spike protein, and (N) the nucleocapsid protein [3]. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a receptor on the human cells surface and it has been shown that SARS-CoV virus, the other cousin of COVID-19, binds to this receptor with its spike protein for entering to the cells. Based on the recent research, ACE2 is also required for SARS-CoV-2 entry into the cells [4]. The ACE2 shows widespread distribution in different organs including brain and neural cells [5]. Clinical symptoms of COVID-19 are range from mild to severe. Fever, cough, and shortness of breath are the most common symptoms of the disease [6].

According to the clinical observation in 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 invades the central nervous system (CNS) and in this way, presumably affects pulmonary function. Respiratory center in the brainstem is considered as a main target of SARS-CoV-2 which leads to respiratory center dysfunction and consequent acute respiratory distress in COVID-19 patients [7]. Although most studies have focused on the respiratory manifestation of COVID-19, but regarding the recent SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, the neurological manifestations of this virus are becoming more and more evident.

The SARS-CoV-2 shows high homology in both genomic sequence and clinical manifestations with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Previous clinical and experimental evidence suggested that brain is a major target of the coronaviruses [3]. These viruses have also been detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of SARS and MERS infected patients in the early 2000s [8]. Moreover, SARS-CoV virus antigen was detected abundantly in the olfactory bulb, piriform and infra-limbic cortices, basal ganglia (ventral pallidum and lateral preoptic regions), and midbrain (dorsal raphe) in the infected patients [9]. Due to the mentioned similarities between SARS-CoV-2 and other beta coronaviruses, it is not unexpected that COVID-19 patients show the neurological symptoms and complications. Many patients with novel coronavirus have reported different range of neurological symptoms from mild and non-specific symptoms such as headache, nausea, vomiting, languidness, myalgia, and unstable walking to more complex symptoms like cerebral hemorrhage, meningitis, encephalitis, and other neurological complications [10,11].

It has been indicated that SARS-CoV-2 may enter to the CNS through hematogenic rout, retrograde or anterograde neuronal transport [12,13]. Understanding the virus neuroinvasion pathway help researchers to better identify pathological related consequences of infection and in this way, the diagnostic criteria as well as management and treatment of the disease can be improved.

In this review article, we summarize the mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 entry, neurological symptoms of the COVID-19 infection in central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS), immune neuropathology of the virus, and the impacts of the virus on other neurological disorders.

2. The SARS-CoV-2 entering mechanisms to the nervous tissue

Although there are several suggested routs for entering of the SARS-CoV-2 to the nervous system, the exact mechanism of its neuroinvasion is not clear. The virus may directly invade the nervous tissue because of its detection in the CSF or brain tissue. In order to invade different organs, the SARS-CoV-2 may spread through the bloodstream. Viremia results in virus transcytosis across the endothelial cells of blood brain barrier (BBB) or the virus infects epithelial cells of the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB) in the choroid plexus (CP) of the brain ventricles. Moreover, leukocytes may be infected and transport the virus as a vector. In order to access the CNS, the virus uses the axonal transport machinery (retrograde transport). In addition to hematic rout, lymphatic rout is also considered to be a possible pathway for the virus to enter the CNS. Direct viral invasion is another hypothesis for the entering of virus to the CNS. The SARS-CoV-2 may invade the nervous tissue through the ACE2 or TMPRSS2 receptors. These receptors have shown wide distribution in the body. Interestingly, the ACE2 receptor is also expressed on the membrane of spinal cord and the virus may invade the spinal cord through its binding to the ACE2 receptors on the surface of neurons [14,15]. The SARS-CoV-2 may penetrate cribriform plate close to the olfactory bulb (OB) and the olfactory epithelium (OE). In this way, virus enters to the CNS. Anosmia or hyposmia as new presentations of COVID-19 patients confirm this route of infection. Moreover, COVID-19 cuisine, SARS-CoV showed a transneural penetration through the olfactory bulb in a mice model [9]. The SARS-CoV-2 may infect olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) or non-neural cells located in the OE using ACE2 or TMPRSS2 receptors. Neuronal infection with COVID-19 results in SARS-CoV-2 uptake into the ciliated dendrites/soma and the virus can use anterograde axonal machinery transport along the olfactory nerve [16]. In addition to neuronal cells, the virus may cross the non-neuronal OE cells and directly enter to the CSF around the olfactory nerve bundles [17]. The ACE2 and TMPRSS2 receptors are highly expressed in the human and mouse olfactory mucosa and their expression increases in murine model with age [16]. The ACE2 receptor is also expressed in both neurons and glia cells [5]. Hence the elderly individuals may be at higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 accumulation in the OE cells [[18], [19], [20]]. Moreover, the ACE2-independent virus infection could be also considered for entering of virus into the CNS. Specialized glia cells known as olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs) are closely associated with axons and can supply axons with macromolecules by the way of extracellular vesicle (EVs). These extracellular vesicles could be regarded as another way of the virus transfer from the OEC to the ORN axon which is ACE2 independent [5]. In addition to the olfactory nerve, the virus may use other peripheral nerves such as trigeminal or the sensory fibers of the vagus nerve which innervates different parts of the respiratory tract including larynx, trachea, and lungs [21,22].

3. The neuropathology of SARS-CoV-2

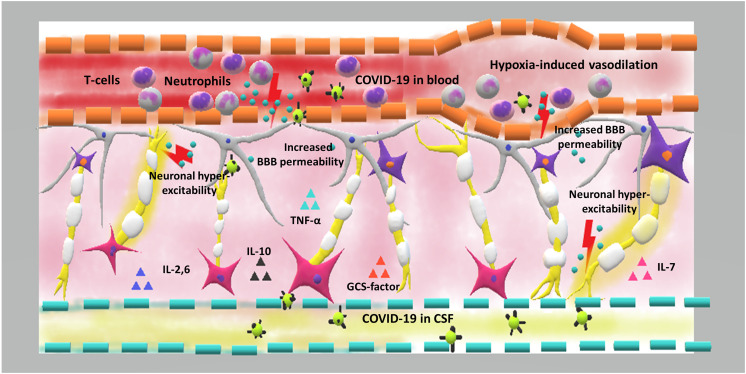

The neuroinvasive feature of SARS-CoV-2 can damage the nervous system through different neuropathological mechanisms. Owing to similar structure and infection pathway between SARS-CoV-2 and the other coronavirus family members, similar mechanism of neuropathology could be expected [23]. One of the most widely accepted neuropathological mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 is hyperinflammatory state. The over-exuberance response of immune system results in release of a large amount of cytokines and chemokines such as interleukins 2, 6, 7, and 10, tumor necrotizing α, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [24]. The released factors change the permeability of the BBB and increase the activation of neuroinflammatory cascades. Moreover, some of these cytokines can drive neuronal hyper-excitability via glutamate receptors activation and lead to an acute form of seizures [25,26]. An inflammatory theory of SARS-CoV-2 infection can also be supported by steroid response of a COVID-19 patients with severe encephalitis [27]. Moreover, it is suggested that over exuberance response of immune system in SARS-COV-2 infection may lead to inflammatory injury and edema in the brain. This process leads to alterations in the consciousness of these patients [28]. The inflammatory and immunologic responses lead to a cytokine storm. Some of the patients with severe COVID-19 may presented with cytokine storm syndrome [29]. Intracranial cytokine storms result in BBB breakdown and increased leukocyte migration. In this process, the virus doesn't have direct invasion or para-infectious demyelination [30].

Hypoxia is another process which results in nervous tissue damage. Virus proliferation and subsequent alveolar dysfunction lead to hypoxia in the CNS. Additionally, increased anaerobic metabolism, cerebral vasodilation, cerebral blood supply obstruction, and headache due to ischemia and congestion are occurred following virus infection. If the hypoxia continues, the brain function worsens and may even lead to coma or death [31]. Severe hypoxia also may result in acute cerebrovascular disorder such as acute ischemic stroke [32]. It has also been demonstrated that COVID-19 patients often show severe hypoxia and viremia which increase the risk of toxic encephalopathy [32]. Since, COVID-19 cases often suffer from sever hypoxia, this process may play a critical role in the nervous system damage following virus infection [33].

It has been shown that patients with COVID-19 lose senses of smell and taste. The smell loss may be due to direct damage to the olfactory bulb and the inflammatory response in the nasal cavity, which blocks the binding of odorants to the olfactory receptors. It takes a long time for damaged neurons to form successful synapses with the olfactory bulb [34]. Regarding to taste sense dysfunction, cytokines molecules in COVID-19 patients may target taste buds and cause ageusia [35]. Another hypothesis for altered taste sense is related to ability of SARS-CoV-2 for occupying sialic acid binding site on the taste buds which results in accelerating the degradation of the gustatory particles [35]. Fig. 1 shows the immune pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 1.

The immune pathogenesis of COVID-19 in the CNS.

Hypoxia is considered as a key player in COVID-19 associated CNS pathology. Alveolar dysfunction results in brain hypoxia that is followed by cerebral vasodilation, increased anaerobic metabolism, and ischemia. On the other hand, over-activation of the immune system and increased release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as interleukins 2, 6, 7, and 10, tumor necrotizing α, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor change the blood brain barrier permeability and these factors allow the virus to enter into the central nervous system. Moreover, some of these cytokines activate glutamate receptors and cause neuronal hyper-excitability, leading to acute seizures.

4. CNS manifestation of the COVID-19

It has been shown that SARS-CoV-2 infects the brain and spinal cord of the patients. The first case of spinal cord involvement was observed in a 66-year-old man with a post-infectious acute myelitis presentation. Acute myelitis was diagnosed due to the acute flaccid myelitis of lower limbs, urinary and bowel incontinence, and sensory level at T10. Moreover, any obvious abnormality in cranial nerve examination was not reported [15]. In a retrospective, observational case series study, Mao et al. evaluated 214 confirmed SARS-CoV-2 patients for their neurological manifestation. The patients have manifested for both CNS and PNS symptoms as well as skeletal muscle injury and among those, CNS symptoms were the predominant form of neurologic manifestation in patients with COVID-19. It has also been noted that neurological dysfunction was greater in those with severe infection. Higher level of D-dimer was observed in cases with severe infection compared to patients with non-severe infection which might be considered for the higher incidence of cerebrovascular disease in patients with severe infection. Furthermore, patients with CNS symptoms had lower levels of lymphocyte count that shows immunosuppression in these patients [10]. In a single-center retrospective study, a number of 221 COVID-19 patients were analyzed for presenting new onset acute cerebrovascular disease (CVD). Among those, 13 patients showed CVD. Patients with CVD were older and had many risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes, and higher level of C-reactive protein compared to patients without CVD [36]. Moriguchi et al. reported the first case of meningitis/encephalitis in COVID-19 patients. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an abnormal presentation of medial temporal lobe including hippocampus which indicates encephalitis, hippocampal sclerosis or post convulsive encephalitis. The patient also showed pan-paranasal and paranasal sinusitis. In order to better and earlier diagnose of SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is important to pay more attention to the nasal and paranasal conditions [13]. Sohal et al. reported seizures in a 72-year-old man patient with COVID-19 infection. However, chronic microvascular ischemic alteration was detected in computed tomography (CT) of the head, but there was no evidence of infarct or hemorrhage [37]. Another report of seizure in COVID-19 patients was studied in a 30-year-old female. This patient was presented with generalized tonic-clonic seizure. Brain MRI was normal and her seizures were recurring (five times) approximately every 8 h [38]. Filatov et al., reported encephalopathy in a 74-year-old male who was positive for COVID-19. No acute abnormalities were observed in the CT of the head and EEG findings was consistent with an encephalopathy and focal left temporal lobe dysfunction. However, the CSF analysis was normal [39]. A 54-year-old patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection was reported with specific neurological manifestation. The brain CT showed bilateral basal ganglia involvement and a subacute hemorrhagic insult [40]. Pilotto et al. reported a 60-year-old man presented with severe alteration of consciousness. The patient diagnosed with encephalopathy and his laboratory testing showed an increased level of D-dimer. The CSF analysis revealed a mild lymphocytic pleocytosis and the CSF proteins were increased [27]. Encephalitis associated with SARS-CoV-2 was also reported in a male COVID-19 patient. He was positive for meningeal irritation signs including nuchal rigidity, Kernig sign, and Brudzinski sign and extensor plantar response [28]. Acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy is a rare encephalopathy associated with viral infection. This rare manifestation was reported in a female airline worker in her late fifties with COVID-19 infection. She was admitted to the hospital with altered mental status. Her CT of the head showed symmetric hypo-attenuation of the bilateral medial thalami and the MRI images indicated T2 FLAIR hyper-intensity of the bilateral medial temporal lobes and thalami. This is the first reported case of COVID-19 patient with acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy [30]. Lau et al. reported a possible involvement of the CNS by the SARS-CoV-2 in a 32-year-old pregnant woman with myalgia manifestation. The patient showed generalized convulsion which is probably due to the infection of the CNS [41].

5. PNS manifestation of the COVID-19

It has been shown that the SARS-CoV-2 can involve the peripheral nervous system. Anosmia and taste-related changes are as indications of SARS-CoV-2 infection. These manifestations support the idea of olfactory invasion rout of SARS-CoV-2 virus. The first case of COVID-19 patient with an olfactory dysfunction was about a 40-year-old woman with sudden and complete loss of the olfactory function. She had experienced dry cough related to cephalagia and myalgia. Her MRI showed bilateral inflammatory obstruction of the olfactory clefts [42]. The prevalence of smell and taste alteration in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 were calculated about 34% in a study [43]. However, they didn't report any data on these symptoms timing of onset compared to other symptoms. In line with this study and to overcome the data insufficiency, a cross sectional study on 202 patients with SARS-CoV-2 was performed and prevalence, intensity, and timing of an altered sense of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients were analyzed. The results indicated that 130 patients (64.4%) show altered sense of smell or taste. Of these 130 patients, 45 patients (34.6%) also reported blocked nose. Regarding the timing of alteration in sense of smell or taste onset compared to other symptoms, they reported that 24 patients (11.9%) before other symptoms, 46 patients (22.8%) at the same time and 54 patients (26.7%) after other symptoms showed taste and smell alterations [44]. Lechien et al. analyzed a total of 417 mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients for the olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions. Of 417 patients, 357 patients (85.6%) had olfactory dysfunction which among those, 284 (79.6%) patients showed anosmia, and 73 (20.4%) patients showed hyposmia during the disease course. Furthermore, 12.6% of these patients were phantosmic and 32.4% of patients were parosmic. Similar to the previous report, the timing of alteration in sense of smell or taste onset compared to the other symptoms were also examined in this study. The olfactory dysfunction was occurred before (11.8%), after (65.4%) or at the same time as the appearance of other symptoms (22.8%). Moreover, 342 patients (88.8%) reported gustatory dysfunction. However, any significant association was not found between comorbidities and the development of olfactory or gustatory disorders. It has been estimated that the olfactory dysfunction in 56% of patients will be permanent after resolution of the COVID-19 general symptoms. In 63.0% of patients, the olfactory disorder remained even after other symptoms resolution. Probable reason for lasting these symptoms is infection of both resting and activated horizontal basal cells (HBCs). These reserve stem cells are activated during tissue damages and also express the ACE2 and TMPRSS2 receptors [12]. Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute immune-mediated complication which involves the peripheral nerves and nerve roots and its pathomechanism is similar to an autoimmune disorder [45]. The first case of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) in a patient with COVID-19 was a 65-year-old male with acute progressive symmetric ascending quadriparesis. He had bilateral facial paresis and no urinary and fecal incontinence. Mild herniation of two intervertebral discs was observed in MRI imaging [46]. Although the SARS-CoV-2 mechanism in induction of GBS is not clear, it is suggested that COVID-19 may contribute in the production of antibodies against specific gangliosides which involve in certain forms of GBS [46]. Table 1 summarizes the CNS and PNS manifestations of SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic features of COVID-19 patients with neurological manifestation.

| Case demographic | Diagnosis | General sign & symptoms | Medical history | CT scan of the head | MRI | EEG | Laboratory testing | CNS & PNS involvement | CSF analysis | Treatment | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A 54-year-old woman | Encephalopathy with brain basal ganglia involvement | Cough for the past five days, low-grade fever | Diabetes, hypertension, a history of lumbar spinal laminectomy and fusion surgery | Acute to sub-acute changes evident of bilateral basal ganglia hyper density | Signal change in bilateral basal ganglia | Not reported (N.R) | White blood cell count was within the reference range, serum and urine ketone were negative, All electrolytes were in the reference range, blood glucose level was 250 mg/dL | Sudden and complete loss of the olfactory function without nasal obstruction | Impossible due to previous lumbar surgeries and scarring | Hydroxychloroquin, levofloxacin, naproxen, oral lopinavir/indinavir | The patient's vital signs and general condition stabilized | [40] |

| A 74-year-old male | Encephalopathy | Fever and cough | Atrial fibrillation, cardio embolic stroke, Parkinson's disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and recent cellulitis | No acute changes, There is an area of hypo density in the right temporal region | N.R | Diffuse slowing and focal slowing, sharply contoured waves in the left temporal region | N.R | Headache, altered mental status | Showed no evidence of CNS infection | Vancomycin, meropenem, acyclovir, hydroxychloroquine lopinavir/ritonavir | N.R | [39] |

| A 66-year-old man | Post-infectious acute myelitis | Fever and fatigue, no obvious abnormality in cranial nerve examination | Bilateral basal ganglia and paraventricular lacunar infarction, brain atrophy | Not performed (N·P) | N·P | Positive nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19, elevated levels of ALT and AST | Acute flaccid paralysis of bilateral lower limbs, urinary, bowel incontinence | N·P | Ganciclovir, lopinavir/ritonavir, moxifloxacin, dexamethasone, human immunoglobulin and mecobalamin | Bilateral lower extremities were ameliorated | [15] | |

| A 24-year-old man | Meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-CoV-2 | Generalized fatigue and fever, sore throat, paranasal sinusitis | No episodes of mesial temporal epilepsy | No evidence of brain edema | Hyper intensity along the wall of inferior horn of right lateral ventricle, hyper intense signal changes in the right mesial temporal lobe and hippocampus with slight hippocampal atrophy | N·P | Increased white cell count, Neutrophil dominant, decreased lymphocytes, increased C-reactive protein | Unconsciousness, transient generalized seizures, neck stiffness | Specific SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in CSF, The CSF cell count was 12/mL–10 mononuclear and 2 polymorphonuclear cells without red blood cells | Intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone, vancomycin, aciclovir and steroids, intravenous levetiraceta, favipiravir | N.R | [13] |

| A 72-year old man | Seizures | Weakness, lightheadedness after experiencing a hypoglycemic episode, fever | Hypertension, coronary artery disease with stent, diabetes type 2, end stage kidney disease on hemodialysis | Chronic micro vascular ischemic changes but did not show any acute changes infarct or hemorrhage | MRI brain was not completed due the patient being too unstable for transport | Six left temporal seizures and left temporal sharp waves which were epileptogenic | Elevated CRP, lymphopenia, leukopenia, elevated Troponin | Multiple episodes of tonic colonic movements of his upper and lower extremities | Patient died before lumbar puncture could be arranged | Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, vancomycin and piperacillin tazobactam, valproate | Died | [37] |

| A 30-year-old female | Frequent convulsive seizures | Dry cough, fever and fatigue | No past medical history | N·P | Brain MRI was normal | N·P | Mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR = 35 mm/h), normal C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell count 5500 cells per microliter with 26% lymphocytes and 70% neutrophils | Generalized tonic-clonic seizure | Normal protein, glucose, with five cell counts but was unremarkable for COVID-19 infection. | Intravenous phenytoin and levetiracetam, chloroquine, lopinavir-ritonavir | The symptoms of the patient improved with anticonvulsive and antiviral medications. | [38] |

| A 60-year-old man | Steroid-responsive encephalopathy | Fever, cough | N.R | Brain CT scan was unremarkable | did not reveal significant alterations or contrast-enhanced areas within brain and/or meninges | Generalized slowing, more prominent on the anterior regions with decreased reactivity to acoustic stimuli | Normal blood cell counts, increased D-dimer (968 ng/mL) but normal levels of CRP, fibrinogen and ferritin | Severe encephalopathy, cognitive fluctuations, progressive irritability, confusion and asthenia, severe alteration of consciousness. | Inflammatory findings with mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (18/uL) and moderate increase of CSF protein (696 mg/dL) | Lopinavir/ritonavir hydroxychloroquine, high intravenous steroid treatment (methylprednisolone | The clinical response to steroid therapy was quite impressive, the clinical conditions of the patient improved |

[27] |

| A 32-year-old pregnant woman | Generalized tonic-clonic convulsion | Fever, chills, unproductive cough and no sore throat | No medical history | N.R | N.R | N.R | Total leukocyte count was 12.3 × 109/L and lymphocyte count was 1.6 × 109/L. Hemoglobin level, liver and renal function tests, and serum lactate dehydrogenase were normal | Myalgia | Positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV | Hydrocortisone, ribavirin, piperacillin/tazobactam | N.R | [41] |

| A Wuhan male | Encephalitis | Fever, shortness of breath | N.R | CT was normal | N.R | N.R | Low WBC count (3.3 × 109/L) and lymphopenia (0.8 × 109/L). | Myalgia, confusion, nuchal rigidity, Kernig sign and Brudzinski sign and extensor plantar response | The cerebrospinal fluid pressure was 220 mmHg. Laboratory tests with CSF showed WBC (0.001 × 109/L), protein (0.27 g/L), ADA (0.17 U/L) and sugar (3.14 mmol/L) contents within normal limits, negative for SARS-CoV-2 | Arbidol and oxygen therapy, mannitol infusion | CSF pressure gradually reduces and the patient's consciousness gradually improves. | [28] |

| A 65-years- old male | Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) | Cough, fever and sometimes dyspnea | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | N.R | Normal finding except for mild herniation of two intervertebral discs. | N.R | White blood cell count 14,700 cells per microliter (neutrophils = 82.7%; lymphocytes = 10.4%), alanine aminotransferase 35 IU/L; aspartate aminotransferase 47 IU/L; | Acute progressive symmetric ascending quadriparesis, acute progressive weakness of distal lower extremities, facial paresis bilaterally | N·P | Hydroxychloroquin, lopinavir, ritonavir, and azithromycin | N.R | [46] |

| A 50-year-old man | Miller Fisher syndrome | Cough, malaise, headache, low back pain, and a fever | Bronchial asthma |

N.R | N.R | N.R | Lymphopenia (1000 cells/uL) and elevated C-reactive protein (2.8 mg/dL), positive to the antibody GD1b-IgG | Anosmia, Ageusia, right internuclear ophthalmoparesis, right fascicular oculomotor palsy, ataxia, areflexia, albuminocytologic dissociation | An opening pressure of 11 cm of H2O, white blood cell count = 0/μL, protein = 80 mg/dL, glucose = 62 mg/dL, with normal cytology | Immunoglobulin and acetaminophen | Resolution of the neurological features, except for residual anosmia and ageusia. |

[47] |

| A 39-year-old man | Polyneuritis Cranialis | A low-grade fever, diarrhea | Past medical history was unremarkable | N.R | N.R | N.R | Normal electrolytes, leukopenia (3100 cells/uL) | Ageusia, Bilateral abducens palsy, Areflexia and albuminocytologic dissociation | An opening pressure of 10 cm H2O, white blood cell count = 2/μL (all monocytes), protein = 62 mg/dL, glucose = 50 mg/dL, with normal cytology | Acetaminophen and Telemedicine |

Complete eye movements, complete neurological recovery | [47] |

| A female airline worker in her late fifties | Acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy | A 3-day history of cough, fever | N.R | Symmetric hypo attenuation within the bilateral medial thalami with a normal CT angiogram and CT venogram | Hemorrhagic rim enhancing lesions within the bilateral thalami, medial temporal lobes, and subinsular regions | N.R | N.R | Altered mental status | CSF analysis was limited due to a traumatic lumbar puncture | Intravenous immunoglobulin | N.R | [30] |

N.R: Not reported; N·P: Not performed.

6. The impacts of COVID19 on neurological disorders

The COVID-19 pandemic as an external stressor has several short-term as well as long-term advers effects on a large groups of people, especially some with underlying diseases such as neurological disorders. Parkinson's disease (PD) is one of these neurological complication which ethiologically affects dopamine-producing (“dopaminergic”) neurons due to the accumulation of α-synuclein (α-syn) aggregates in a specific area of the brain called substantia nigra [48]. PD is also reported to endanger the respiratory system [49]. The COVID-19 pandemic increases stress among population and exacerebrates different motor symptoms, such as tremor, freezing of gait or dyskinesias, [50] and also diminished the efficacy of dopaminergic medication [[51], [52], [53]]. Interestingly, association between COVID-19 pathophysiology and alteration in dopamin synthesis pathwayhas been hypothetized. It has been demonstrated that Dopa Decarboxylase (DDC), a major enzyme of both dopamine and serotonin synthetic pathways, is significantly co-expressed with ACE2 receptor. On the other hand, SARS-COV virus, the other causin of COVID-19, induces the ACE2 down-regulation which could be consistant with dopamine synthesis alteration [54]. Interestingly, dopamine receptors are expressed in the alveolar epithelial cells and probably dopamine contributes in lung immunity [55]. Although the above mentioned notes about dopammine, ACE2, and COVID-19 are not overt, these evidence put this hypothesis in researcher's mind which defective expression of the ACE2 and DDC may alter dopamin levels in the blood of patients with COVID-19. Moreover, dysregulation of dopamine may worsen the severity of PD [56]. In addition to the impact of COVID-19 on PD patients, the virus may cause sporadic PD in infected individuals. The Braak hypothesis says that a neuroinvasive virus could enter to the CNS through the nasal cavity and the gastrointestinal tract [57].

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is another neurological disease that COVID-19 infection may threat in individuals with MS. The mortality/morbidity risk in MS patients with COVID-19 who are treated with disease modifying therapies (DMTs), is probably quite moderate to low. Moreover, adminstration of immunomodulatory drugs in these patients leads to limited lung capacity which increases the risk of COVID-19 related pneumonia [58]. Decision for stopping or continuing the DMT for MS patients infected with COVID-19 depends on individual factors such as disease severity and activity [59]. Moreover, sever complication of COVID-19 infection results from an over-reaction of immune system to the virus [59]. Ramanathan et al. hypothesised that moderate immunosuppression therapy which is taken for MS patients may increase the risk of severe COVID-19 complications [60]. In this line, several trials have been performed to examine the ability of immunosuppressive drugs for mitigating the immune response to the virus [61,62].

7. Conclusion and future prospects

COVID-19 patients may show neurological manifestations such as headache, consciousness disorder, and other pathological signs. The main symptom of SARS-CoV-2 is related to the respiratory system. However it has been suggested that the respiratory manifestation may associated with the virus invasion to the cardio-respiratory center in the brain stem. According to the reports, neurological symptoms in COVID-19 patients are associated with disease severity. Although these neurological manifestation are rare, they can cause serious complications if not diagnosed and managed early. Since neurological manifestation are often non-specific at the early stages of COVID-19 infection, the risk of misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis will increase. Due to the serious impacts of COVID-19 on the nervous system, more studies are needed to elucidate the long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the nervous system function and it is of interest to shedding light on the exact mechanisms of its neuroinvasion. Moreover, in order to find the neuroinvasive behaviors of SARS-CoV-2, further in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to be performed.

Declarations of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

There are no funders to report for this study.

References

- 1.Spinelli A., Pellino G. COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives on an unfolding crisis. Br. J. Surg. 2020;10 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang T., Wu Q., Zhang Z. Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:1346–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H., Penninger J.M., Li Y., Zhong N., Slutsky A.S. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baig A.M., Khaleeq A., Ali U., Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host–virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020;11:995–998. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen S.A., Smulian J.C., Lednicky J.A., Wen T.S., Jamieson D.J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;222:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machado C., Gutierrez J.V. 2020. Brainstem Dysfunction in SARS-COV2 Infection Can be a Potential Cause of Respiratory Distress. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung E.C., Chim S.S., Chan P.K., Tong Y.K., Ng E.K., Chiu R.W., Leung C.-B., Sung J.J., Tam J.S., Lo Y.D. Detection of SARS coronavirus RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:2108–2109. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.025437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Netland J., Meyerholz D.K., Moore S., Cassell M., Perlman S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J. Virol. 2008;82:7264–7275. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00737-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M., Hu Y., Chen S., He Q., Chang J., Hong C., Zhou Y., Wang D. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA neurology. 2020;77:683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H.-Y., Li X.-L., Yan Z.-R., Sun X.-P., Han J., Zhang B.-W. Potential neurological symptoms of COVID-19. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2020;13 doi: 10.1177/1756286420917830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brann D., Tsukahara T., Weinreb C., Logan DW., Datta SR. Non-neural expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory epithelium suggests mechanisms underlying anosmia in COVID-19 patients. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriguchi T., Harii N., Goto J., Harada D., Sugawara H., Takamino J., Ueno M., Sakata H., Kondo K., Myose N. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemoto W., Yamagata R., Nakagawasai O., Nakagawa K., Hung W.-Y., Fujita M., Tadano T., Tan-No K. Effect of spinal angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activation on the formalin-induced nociceptive response in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020;872 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.172950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao K., Huang J., Dai D., Feng Y., Liu L., Nie S. MedRxiv; 2020. Acute Myelitis after SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Case Report. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butowt R., Bilinska K. SARS-CoV-2: olfaction, brain infection, and the urgent need for clinical samples allowing earlier virus detection. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020;11:1200–1203. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harberts E., Yao K., Wohler J.E., Maric D., Ohayon J., Henkin R., Jacobson S. Human herpesvirus-6 entry into the central nervous system through the olfactory pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:13734–13739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105143108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanageswaran N., Demond M., Nagel M., Schreiner B.S., Baumgart S., Scholz P., Altmüller J., Becker C., Doerner J.F., Conrad H. Deep sequencing of the murine olfactory receptor neuron transcriptome. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olender T., Keydar I., Pinto J.M., Tatarskyy P., Alkelai A., Chien M.-S., Fishilevich S., Restrepo D., Matsunami H., Gilad Y. The human olfactory transcriptome. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:619. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2960-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saraiva L.R., Ibarra-Soria X., Khan M., Omura M., Scialdone A., Mombaerts P., Marioni J.C., Logan D.W. Hierarchical deconstruction of mouse olfactory sensory neurons: from whole mucosa to single-cell RNA-seq. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–17. doi: 10.1038/srep18178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Audrit K.J., Delventhal L., Aydin Ö., Nassenstein C. The nervous system of airways and its remodeling in inflammatory lung diseases. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367:571–590. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Driessen A.K., Farrell M.J., Mazzone S.B., McGovern A.E. Multiple neural circuits mediating airway sensations: recent advances in the neurobiology of the urge-to-cough. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2016;226:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y., Bai W., Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients [published online ahead of print February 27, 2020] J. Med. Virol. 2020:10. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Liu H., Wu Y., Zhang L., Yu Z., Fang M., Yu T. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Libbey J.E., Kennett N.J., Wilcox K.S., White H.S., Fujinami R.S. Interleukin-6, produced by resident cells of the central nervous system and infiltrating cells, contributes to the development of seizures following viral infection. J. Virol. 2011;85:6913–6922. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00458-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singhi P. Infectious causes of seizures and epilepsy in the developing world. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2011;53:600–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pilotto A., Odolini S., Masciocchi S., Comelli A., Volonghi I., Gazzina S., Nocivelli S., Pezzini A., Caruso A., Leonardi M. 2020. Steroid-Responsive Severe Encephalopathy in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. (medRxiv) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye M., Ren Y., Lv T. Encephalitis as a clinical manifestation of COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;1591:30465–30467. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehta P., Mcauley D., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R., Manson J., Collaboration S. Correspondence COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and. Lancet. 2020;6736:19–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poyiadji N., Shahin G., Noujaim D., Stone M., Patel S., Griffith B. COVID-19–associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features. Radiology. 2020;201187:1–5. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdennour L., Zeghal C., Deme M., Puybasset L. 2012. Interaction brain-lungs. Annales francaises d’anesthesie et de reanimation; pp. e101–e107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo Y.-R., Cao Q.-D., Hong Z.-S., Tan Y.-Y., Chen S.-D., Jin H.-J., Tan K.-S., Wang D.-Y., Yan Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak–an update on the status. Military Medical Research. 2020;7:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Y., Xu X., Chen Z., Duan J., Hashimoto K., Yang L., Liu C., Yang C. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soler Z.M., Patel Z.M., Turner J.H., Holbrook E.H. Wiley Online Library; 2020. A Primer on Viral-Associated Olfactory Loss in the Era of COVID-19. International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaira L.A., Salzano G., Fois A.G., Piombino P., De Riu G. Wiley Online Library; 2020. Potential Pathogenesis of Ageusia and Anosmia in COVID-19 Patients. International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, Y., Wang, M., Zhou, Y., Chang, J., Xian, Y., Mao, L., Hong, C., Chen, S., Wang, Y., Wang, H., 2020b. Acute cerebrovascular disease following COVID-19: a single center, retrospective, observational study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Sohal S., Mossammat M. COVID-19 presenting with seizures. IDCases. 2020;20:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00782. e00782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karimi N., Sharifi Razavi A., Rouhani N. Frequent convulsive seizures in an adult patient with COVID-19: a case report. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2020;22:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filatov A., Sharma P., Hindi F., Espinosa P.S. Neurological complications of coronavirus disease (COVID-19): encephalopathy. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haddadi K., Ghasemian R., Shafizad M. Basal ganglia involvement and altered mental status: a unique neurological manifestation of coronavirus disease 2019. Cureus. 2020;12:1–8. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lau K.-K., Yu W.-C., Chu C.-M., Lau S.-T., Sheng B., Yuen K.-Y. Possible central nervous system infection by SARS coronavirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:342. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eliezer M., Hautefort C., Hamel A.-L., Verillaud B., Herman P., Houdart E., Eloit C. Sudden and complete olfactory loss function as a possible symptom of covid-19. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2020;0832:1–2. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giacomelli, A., Pezzati, L., Conti, F., Bernacchia, D., Siano, M., Oreni, L., Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in SARS-CoV-2 patients: a cross-sectional study [published online March 26, 2020]. Clin. Infect. Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Spinato G., Fabbris C., Polesel J., Cazzador D., Borsetto D., Hopkins C., Boscolo-Rizzo P. Alterations in smell or taste in mildly symptomatic outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2020;323:2089–2090. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sejvar J.J., Baughman A.L., Wise M., Morgan O.W. Population incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36:123–133. doi: 10.1159/000324710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sedaghat Z., Karimi N. Guillain Barre syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: a case report. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020;76:233–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gutiérrez-Ortiz C., Méndez A., Rodrigo-Rey S., San Pedro-Murillo E., Bermejo-Guerrero L., Gordo-Mañas R., de Aragón-Gómez F., Benito-León J. Miller fisher syndrome and polyneuritis cranialis in COVID-19. Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009619. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Triarhou L.C. Landes Bioscience; 2013. Dopamine and Parkinson’s Disease. Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Helmich R.C., Bloem B.R. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson’s disease: hidden sorrows and emerging opportunities. J. Park. Dis. 2020;10:351–354. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zach H., Dirkx M.F., Pasman J.W., Bloem B.R., Helmich R.C. Cognitive stress reduces the effect of levodopa on Parkinson's resting tremor. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2017;23:209–215. doi: 10.1111/cns.12670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ehgoetz Martens K.A., Hall J.M., Georgiades M.J., Gilat M., Walton C.C., Matar E., Lewis S.J., Shine J.M. The functional network signature of heterogeneity in freezing of gait. Brain. 2018;141:1145–1160. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Macht M., Kaussner Y., Möller J.C., Stiasny-Kolster K., Eggert K.M., Krüger H.P., Ellgring H. Predictors of freezing in Parkinson’s disease: a survey of 6,620 patients. Mov. Disord. 2007;22:953–956. doi: 10.1002/mds.21458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zach H., Dirkx M., Pasman J.W., Bloem B.R., Helmich R.C. The patient’s perspective: the effect of levodopa on Parkinson symptoms. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2017;35:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuba K., Imai Y., Rao S., Gao H., Guo F., Guan B., Huan Y., Yang P., Zhang Y., Deng W. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus–induced lung injury. Nat. Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bone N.B., Liu Z., Pittet J.F., Zmijewski J.W. Frontline science: D1 dopaminergic receptor signaling activates the AMPK-bioenergetic pathway in macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells and reduces endotoxin-induced ALI. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017;101:357–365. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3HI0216-068RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nataf S. An alteration of the dopamine synthetic pathway is possibly involved in the pathophysiology of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25826. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rietdijk C.D., Perez-Pardo P., Garssen J., van Wezel R.J., Kraneveld A.D. Exploring Braak’s hypothesis of Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2017;8:37. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baysal-Kirac L., Uysal H. COVID-19 associate neurological complications. Neurological Sciences and Neurophysiology. 2020;37(1) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giovannoni G., Hawkes C., Lechner-Scott J., Levy M., Waubant E., Gold J. The COVID-19 pandemic and the use of MS disease-modifying therapies. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2020;39:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramanathan K., Antognini D., Combes A., Paden M., Zakhary B., Ogino M., MacLaren G., Brodie D., Shekar K. Planning and provision of ECMO services for severe ARDS during the COVID-19 pandemic and other outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:518–526. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barzegar M., Mirmosayyeb O., Nehzat N., Sarrafi R., Khorvash F., Maghzi A.-H., Shaygannejad V. COVID-19 infection in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod. Neurology-Neuroimmunology Neuroinflammation. 2020;7 doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Foerch C., Friedauer L., Bauer B., Wolf T., Adam E.H. Severe COVID-19 infection in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2020;42:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102180. 102180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]