Abstract

Background and Aims

Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract [LIFT] and advancement flap [AF] procedures are well-established, sphincter-preserving procedures for closure of high perianal fistulas. As surgical fistula closure is not commonly offered in Crohn’s disease patients, long-term data are limited. This study aims to evaluate outcomes after LIFT and AF in Crohn’s high perianal fistulas.

Methods

All consecutive Crohn’s disease patients ≥18 years old treated with LIFT or AF between January 2007 and February 2018 were included. The primary outcome was clinical healing and secondary outcomes included radiological healing, recurrence, postoperative incontinence and Vaizey Incontinence Score.

Results

Forty procedures in 37 patients [LIFT: 19, AF: 21, 35.1% male] were included. A non-significant trend was seen towards higher clinical healing percentages after LIFT compared to AF [89.5% vs 60.0%; p = 0.065]. Overall radiological healing rates were lower for both approaches [LIFT 52.6% and AF 47.6%]. Recurrence rates were comparable: 21.1% and 19.0%, respectively. In AF a trend was seen towards higher clinical healing percentages when treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor/immunomodulators [75.0% vs 37.5%; p = 0.104]. Newly developed postoperative incontinence occurred in 15.8% after LIFT and 21.4% after AF. Interestingly, 47.4% of patients had a postoperatively improved Vaizey Score [LIFT: 52.9% and AF: 42.9%]. The mean Vaizey Score decreased from 6.8 [SD 4.8] preoperatively to 5.3 [SD 5.0] postoperatively [p = 0.067].

Conclusions

Both LIFT and AF resulted in satisfactory closure rates in Crohn’s high perianal fistulas. However, a discrepancy between clinical and radiological healing rates was found. Furthermore, almost half of the patients benefitted from surgical intervention with respect to continence.

Keywords: Perianal fistula, Crohn’s disease, surgery

1. Introduction

Perianal fistulas are difficult to close, especially in patients with Crohn’s disease. Epidemiological studies suggest that up to one-third of all Crohn disease patients will have at least one fistula during the course of their disease.1 Perianal fistulas fundamentally affect the quality of life [QoL] and can cause considerable morbidity. In contrast to simple, low fistulas that can be treated successfully with fistulotomy, there is no ‘gold standard’ treatment approach for high perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease.

Nowadays it is recommended to start all treatment of high perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease patients with the insertion of a non-cutting seton, often combined with antibiotics.2 The non-cutting seton ensures drainage, thereby preventing abscess formation, and is usually removed after a couple of weeks in patients with subsequent medical therapy and/or surgery. Medical treatment can be optimized with anti-tumour necrosis factor [anti-TNF], which has been demonstrated to induce fistula healing in up to 50% of cases.3 Recent reports suggest that serum concentrations for infliximab should be ≥5 µg/mL for fistula healing, compared to ≥3.5 µg/mL for sustained luminal response.4–6 For new medical therapies such as vedolizumab and ustekinumab, the results are less promising.7 A recent systematic review could not demonstrate a significantly higher closure rate after vedolizumab or ustekinumab when compared to placebo. However, it should be noted that these short-term results were based only on post-hoc analysis from randomized control trials for luminal disease.3

After seton drainage and optimization of medical therapy, surgical closure can be attempted in patients without anorectal stenosis and/or proctitis. High perianal fistulas should be closed with sphincter-saving procedures due to the risk of incontinence. The best established sphincter-saving procedure is the endorectal advancement flap [AF],8 a flap of [sub]mucosal tissue to cover the internal opening of the fistula tract. An alternative to AF is ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract [LIFT] during which the fistula tract is ligated between the anal sphincters in the intersphincteric plane.9

Different measurements are available to evaluate successful closure of the perianal fistula tract. Most studies use clinical healing parameters to assess closure, such as production on gentle palpation or visible closure of the external opening. However, it has been suggested that these clinical parameters often overestimate the percentage of closure, and therefore magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] is probably more reliable. An advantage of MRI over other imaging techniques is the detection of fibrotic tracts, and patent non-producing tracts, which is related to recurrence.10

The recently published systematic review of Stellingwerf et al.11 showed that most published studies evaluating outcomes of LIFT and AF do not discriminate between Crohn’s and cryptoglandular perianal fistulas. Although surgical closure is today more frequently offered to patients with Crohn’s fistulas, data in this specific patient group remain limited. Only one study has evaluated the LIFT procedure in patients with Crohn’s perianal fistulas, showing a clinical success rate of 53%.12 The overall success rate after AF was 61% based on four studies. So far only two studies have reported the recurrence rate after AF in Crohn’s perianal fistulas, which was 18%. Continence seemed better preserved after the LIFT procedure for both aetiologies.11 However, more research in Crohn’s disease patients is necessary to evaluate postoperative outcomes and to determine predictive factors associated with these outcomes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate outcomes and predictive factors associated with these outcomes after the LIFT and AF procedures in terms of clinical and radiological healing, recurrence, and incontinence in patients with high perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and population

In this retrospective cohort study, all consecutive Crohn’s disease patients ≥18 years old treated with a LIFT or AF procedure between January 2007 and February 2018 for a new or recurrent high perianal fistula were included. A perianal fistula was considered high if the tract was deemed too high to lay open, incorporating an important part of the external anal sphincter. Patients with cryptoglandular fistulas, low perianal fistulas, ileo-anal pouch fistulas, rectovaginal and recto-urinary fistulas, and patients with human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] were excluded. Data were reported following the STROBE Checklist for observational studies. The Medical Ethical Committee at the Amsterdam UMC confirmed that no formal ethical approval was needed for this study. All eligible patients obtained an objection form, and were thereby given the opportunity to withdraw permission for data collection.

2.2. Demographic and outcome variables

Patient demographics, medical history including previous surgeries, medical therapy, and details of surgery and follow-up were collected from medical notes. Patient and fistula demographics included sex, age, history of smoking, familial inflammatory bowel disease [IBD], location of Crohn’s disease, medical therapy [including serum concentrations for anti-TNF if available], seton drainage and seton to surgery interval, previous surgical closure of the fistula tract with LIFT, AF, plug or other procedures, and number of internal and external openings. Outcome variables included clinical healing, radiological healing, recurrences, new primary fistula formation, soiling, incontinence for gas, liquid and solid stools, and operating details including time of procedure, complications and re-interventions.

All patients were retrospectively asked about their pre- and postoperative continence using the Vaizey Incontinence Score.13 In addition, a global change question was asked to determine subjectively whether their continence had improved, remained unchanged or deteriorated since their surgery.

2.3. Surgical technique

LIFT procedures were performed according to previously described LIFT techniques.9,14–17 After confirmation of the course of the tract, the intersphincteric plane was diathermically opened. Thereafter, the fistula tract was dissected and ligated close to the internal [and, if preferred by the surgeon, also the external] sphincter, with an absorbable suture [vicryl 2/0]. The external fistula opening and subcutaneous tract was then excised and/or curetted. The intersphincteric wound was closed with absorbable sutures [vicryl 3/0].

The AF procedure was performed similarly to the previously described technique given by Van Koperen et al.18 The internal opening was excised and the fistula tract curetted. A [sub]mucosal flap [with or without muscle fibres of the internal sphincter] with vital edges was mobilized, after which the internal opening was closed with absorbable sutures [vicryl 2/0]. The internal fistula opening was then covered with the flap of [sub]mucosal tissue, and sutured in the distal rectum [vicryl 2/0]. The surgical technique, LIFT or AF, was chosen by the operating surgeon, based on MRI and peroperative findings. The choice for either LIFT or AF depended on factors such as previous procedures, accessibility of the anus, and level of the internal opening and the tract in the intersphincteric plane.

2.4. Primary and secondary end points

The primary end point was clinical healing, defined as closure of the external opening without discharge of pus or faeces, as determined by the treating surgeon. The date on which clinical healing was first reported in the clinical notes was considered the clinical healing date. Secondary outcomes were radiological healing defined as a fibrotic tract on MRI determined by a radiologist, recurrence defined as re-opening of the external opening or recurrence of symptoms after apparent healing, new primary fistula formation [including transformation to an intersphincteric fistula tract after LIFT], continence impairment [summarizing incontinence for gas, liquid and solid stools and soiling, and measured by the Vaizey Incontinence Score], duration of the procedure, complications and re-interventions [including incision and drainage of an abscess and examination under anaesthesia].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were collected in an electronic database. Continuous normally distributed data were presented using mean and standard deviation [SD] and for non-parametric distributions median and range were used. Categorical data were presented using frequencies and percentages. Patient demographics and outcome parameters were compared between the two groups using the unpaired t test, Mann–Whitney U and chi-squared test or a Fisher’s exact test in the case of small numbers [<5]. Patient demographics and other possible factors associated with clinical healing, recurrence and incontinence were analysed by regression analysis. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to estimate recurrence-free survival. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. A clinical minimally important difference [MID] for improvement in the Vaizey Incontinence Score was determined using a clinical anchor-based method to assess the clinical relevance of changes in this score.19 The MID was calculated from the difference in the Vaizey Incontinence Scores in patients answering ‘deteriorated’ and ‘unchanged’ to the global change question [‘Since your operation, has your continence improved, remained unchanged or deteriorated?’]. The Pearson correlation method was used to calculate the correlation coefficient between the Vaizey Incontinence Score and the global change question and a minimal correlation of ≥0.30 was regarded as acceptable. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS for Windows version 24 [IBM Corp.].

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total of 40 procedures in 37 patients were included: 19 were LIFT procedures and 21 AF procedures. The median age of all patients at surgery was 33.9 years [range 19.2–75.5] and 14 [35.1%] were male [Table 1]. Of the perianal fistulas, three were intersphincteric and 37 were located trans-sphincterically, and none of the included fistulas were horseshoe tracts. The LIFT and AF procedures were performed by or under supervision of one of the two IBD surgeons. Most procedures were preceded by seton drainage [n = 38] with a median duration of 4.6 months [range 1.4–113.7], and 24 procedures were performed in patients whilst using anti-TNF. In all but one procedure a preoperative MRI was made [n = 39]. In nine [22.5%] procedures a previous attempt at surgical closure of the fistula tract had been made [one previous attempt in six patients, and two previous attempts in three patients]. Previous attempts comprised six AF procedures, two LIFT procedures, two plugs, one fistulectomy and one closure of the internal fistula opening combined with injection of stem cells or placebo, as part of a clinical trial.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| LIFT [n = 19] | AF [n = 21] | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n [%] | 6 [31.6] | 9 [42.9] |

| Age, yearsa | 34.5 [21.1–75.5] | 33.3 [19.2–67.2] |

| History of smoking, n [%] | 11 [57.9] | 9 [42.9] |

| Smoking at moment of surgery,bn [%] | 7 [36.8] | 4 [19.0] |

| Familial inflammatory bowel disease, n [%] | 5 [26.3] | 5 [23.8] |

| Stoma, n [%] | 4 [21.1] | 5 [23.8] |

| Location of Crohn’s disease, n [%] | ||

| L1 Ileum | 6 [31.6] | 5 [23.8] |

| L2 Colon | 2 [10.5] | 6 [28.6] |

| L3 Both | 5 [26.3] | 3 [14.3] |

| Missing | 6 [31.6] | 7 [33.3] |

| Use of anti-TNF, n [%] | 15 [78.9] | 9 [42.9] |

| Infliximab | 8 [42.1] | 4 [19.0] |

| Adalimumab | 7 [36.8] | 5 [23.8] |

| Use of immunomodulators, n [%] | 10 [52.6] | 9 [42.9] |

| Azathioprine | 4 [21.1] | 4 [19.0] |

| Methotrexaat | 0 [0.0] | 2 [9.5] |

| Mercaptopurine | 6 [31.6] | 3 [14.3] |

| Use of anti-TNF and/or immunomodulators, n [%] | 16 [84.2] | 12 [57.1] |

| Use of trial medication, n [%] | 2 [10.5] | 0 [0.0] |

| Tacrolimus | 1 [5.3] | 0 [0.0] |

| Vedolizumab | 1 [5.3] | 0 [0.0] |

| Preoperative seton drainage, monthsa | 4.9 [2.1–26.1] | 3.7 [1.4–113.7] |

| Time of procedure, minutesa | 74.0 [27–224] | 62.0 [39–125]- |

| Previous surgical closure,cn [%] | 6 [31.6] | 3 [14.3] |

| >12 months of follow-up, n [%] | 9 [47.4] | 19 [90.5] |

| Number of internal openingsa | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1–2] |

| Number of external openingsa | 1 [1–2] | 1 [0–5] |

| Number of recurrent fistulas, n [%] | 4 [21.1] | 5 [23.8] |

Abbreviations: LIFT, ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract; AF, advancement flap; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

aValues are median [range].

bOr within 3 months prior to surgery.

cPrevious attempt at surgical closure of the fistula tract [LIFT, AF, plug or other].

The proportion of LIFT and AF procedures changed over time. In our centre, the first LIFT procedure in this patient population was performed in May 2014. More regular usage of the LIFT procedure started in 2015. Therefore, follow-up in the two groups differed with a median follow-up of 40.9 months [range 1.3–110.3] in the AF group and 10.1 months [range 1.3–50.3] months in the LIFT group [p = 0.002].

3.2. Clinical healing

Data on clinical healing were missing for one procedure due to inconclusive reports. Overall, clinical healing was observed in 29 out of 39 procedures [74.4%]. A trend was seen towards higher healing rates after LIFT [17/19 = 89.5%] when compared to AF [12/20 = 60.0%] [p = 0.065]. Univariate analyses were performed for multiple variables as presented in Table 2. A trend was seen towards higher clinical healing percentages in AF when treated with anti-TNF/immunomodulators [75.0% vs 37.5%; p = 0.104]. The perioperative serum concentration of anti-TNF was only determined in seven patients, five of whom had a therapeutic level ≥5 µg/mL. Unfortunately, numbers were too small to perform statistical analyses.

Table 2.

Clinical healing

| Combined | LIFT | AF | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No clinical healing [n = 10] | Clinical healing [n = 29] | p | No clinical healing [n = 2] | Clinical healing [n = 17] | p | No clinical healing [n = 8] | Clinical healing [n = 12] | p | |

| Male sex, n [%] | 5 [50.0] | 10 [34.5] | 0.388 | 1 [50.0] | 5 [29.4] | 0.562 | 4 [50.0] | 5 [41.7] | 0.714 |

| Age, yearsa | 40.6 [23.9–55.2] | 33.3 [19.2–75.5] | 0.349 | 43.2 [32.6–53.8] | 34.5 [21.1–75.5] | 0.558 | 40.6 [23.9–55.2] | 27.4 [19.2–67.2] | 0.419 |

| History of smoking, n [%] | 5 [50.0] | 15 [51.7] | 0.846 | 2 [100.0] | 9 [52.9] | 0.845 | 3 [37.5] | 6 [50.0] | 0.583 |

| Smoking at moment of surgery,bn [%] | 1 [10.0] | 10 [34.5] | 0.535 | 0 [0.0] | 7[41.2] | 0.998 | 1[12.5] | 3 [25.0] | 0.746 |

| Familial inflammatory bowel disease, n [%] | 2 [20.0] | 7 [24.1] | 0.940 | 0 [0.0] | 5 [29.4] | 0.999 | 2 [25.0] | 2 [16.7] | 0.999 |

| Stoma, n [%] | 3 [30.0] | 6 [20.7] | 0.549 | 0 [0.0] | 4 [23.5] | 0.999 | 3 [37.5] | 2 [16.7] | 0.302 |

| Preoperative seton drainage, monthsa | 4.0 [1.9 – 8.1] | 4.5 [1.4 – 26.1] | 0.185 | 4.7 [4.6–4.9] | 5.5 [2.1–26.1] | 0.462 | 3.2 [1.9–8.1] | 3.7 [1.4–14.5] | 0.461 |

| Anti-TNF, n [%] | 5 [50.0] | 19 [65.5] | 0.388 | 2 [100.0] | 13 [76.5] | 0.999 | 3 [37.5] | 6 [50.0] | 0.583 |

| Anti-TNF and/or immunomodulators, n [%] | 5 [50.0] | 23 [79.3] | 0.085 | 2 [100.0] | 14 [82.4] | 0.999 | 3 [37.5] | 9 [75.0] | 0.104 |

| Previous surgical closure,cn [%] | 2 [20.0] | 7 [24.1] | 0.789 | 0 [0.0] | 6 [35.3] | 0.999 | 2 [25.0] | 1 [8.3] | 0.327 |

Abbreviations: LIFT, ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract; AF, advancement flap; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

aValues are median [range].

bOr within 3 months prior to surgery.

cPrevious attempt at surgical closure of the fistula tract [LIFT, AF, plug or other].

3.3. Radiological healing

Radiological healing was found in 20 out of 40 [50.0%] postoperative MRIs after a median of 5 months, with no significant difference between LIFT and AF [52.6% vs 47.6%; p = 0.752]. The radiological healing rates seemed to be higher in younger patients in univariate analysis [29.8 vs 39.8 years; p = 0.089], especially after the LIFT procedure [p = 0.016] [Table 3]. In addition, a significantly higher radiological healing rate was seen when anti-TNF and/or immunomodulators were used perioperatively [p = 0.047].

Table 3.

Radiological healing

| Combined | LIFT | AF | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No radio healing [n = 20] | Radio healing [n = 20] | p | No radio healing [n = 9] | Radio healing [n = 10] | p | No radio healing [n = 11] | Radio healing [n = 10] | p | |

| Male sex, n [%] | 7 [35.0] | 8 [40.0] | 0.744 | 3 [33.3] | 3 [30.0] | 0.876 | 4 [36.4] | 5 [50.0] | 0.530 |

| Age, yearsa | 39.8 [19.2–75.5] | 29.8 [19.9–67.2] | 0.089 | 40.3 [24.4–75.5] | 29.8 [21.1–45.0] | 0.016 | 37.6 [19.2–55.2] | 30.1 [19.9–67.2] | 0.855 |

| History of smoking, n [%] | 13 [65.0] | 7 [35.0] | 0.997 | 8 [88.9] | 3 [30.0] | 0.603 | 5 [45.5] | 4 [40.0] | 0.654 |

| Smoking at moment of surgery,bn [%] | 7 [35.0] | 4 [20.0] | 0.079 | 4 [44.4] | 3 [30.0] | 0.026 | 3 [27.3] | 1 [10.0] | 0.999 |

| Anti-TNF, n [%] | 10 [50.0] | 14 [70.0] | 0.201 | 7 [77.8] | 8 [80.0] | 0.906 | 3 [27.3] | 6 [60.0] | 0.138 |

| Anti-TNF and/or immunomodulators, n [%] | 11 [55.0] | 17 [85.0] | 0.047 | 7 [77.8] | 9 [90.0] | 0.476 | 4 [36.4] | 8 [80.0] | 0.054 |

Abbreviations: LIFT, ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract; AF, advancement flap; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

aValues are median [range].

bOr within 3 months prior to surgery.

3.4. Recurrence

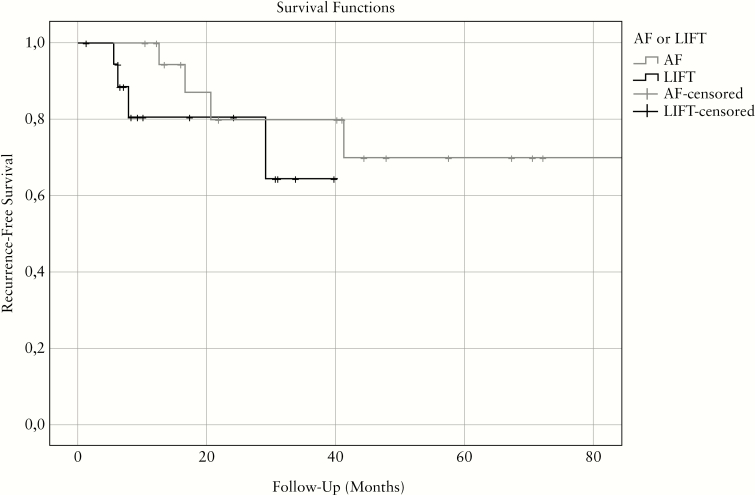

Recurrences occurred in eight out of 40 procedures [20.0%] after a median follow-up of 14.5 months [range 5.5–44.3]: four [21.1%] after LIFT and four [19.0%] after AF [Figure 1]. The Kaplan–Meier estimator of recurrence-free survival suggests that recurrences occur faster after LIFT than after AF. Univariate analyses showed a trend towards a higher recurrence rate after procedures not performed under anti-TNF and/or immunomodulators [50.0% vs 75.0%; p = 0.178] or performed in patients who smoked [62.5% vs 18.8%, p = 0.073] [Table 4]. One fistula tract recurred as an intersphincteric fistula tract, which successfully closed after fistulotomy.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plot of recurrence-free survival after LIFT [n = 19] and AF [n = 21]. LIFT, ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract; AF, advancement flap.

Table 4.

Recurrence

| Combined | LIFT | AF | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No recur. [n = 32] | Recur. [n = 8] | Sign. | No recur. [n = 15] | Recur. [n = 4] | Sign. | No recur. [n = 17] | Recur. [n = 4] | Sign. | |

| Male sex, n [%] | 13 [40.6] | 2 [25.0] | 0.420 | 5 [33.3] | 1 [25.0] | 0.751 | 8 [47.1] | 1 [25.0] | 0.434 |

| Age, yearsa | 33.0 [19.9–67.2] | 42.4 [19.2–75.5] | 0.101 | 32.6 [21.1–53.8] | 52.3 [40.3–75.5] | 0.002 | 33.3 [19.9–67.2] | 34.9 [19.2–49.8] | 0.675 |

| History of smoking, n [%] | 13 [40.6] | 7 [87.5] | 0.311 | 7 [46.7] | 4 [100.0] | 0.762 | 6 [35.3] | 3 [75.0] | 0.979 |

| Smoking at moment of surgery,bn [%] | 6 [18.8] | 5 [62.5] | 0.073 | 5 [33.3%] | 2 [50.0] | 0.079 | 1 [5.9] | 3 [75.0] | 0.511 |

| Anti-TNF, n [%] | 21 [65.6] | 3 [37.5] | 0.158 | 13 [86.7] | 2 [50.0] | 0.136 | 8 [47.1] | 1 [25.0] | 0.434 |

| Anti-TNF and/or immunomodulators, n [%] | 24 [75.0] | 4 [50.0] | 0.178 | 14 [93.3] | 2 [50.0] | 0.067 | 10 [58.8] | 2 [50.0] | 0.749 |

Abbreviations: LIFT, ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract; AF, advancement flap; Recur., recurrence; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

aValues are median [range].

bOr within 3 months prior to surgery.

3.5. Incontinence

The chance of newly developed postoperative incontinence after LIFT was 15.8% and after AF 21.4%.

The mean total Vaizey score prior to surgery was 6.8 [SD 4.8], and after surgery this improved to 5.3 [SD 5.0] [p = 0.067]. Vaizey scores were missing after two procedures as the patients were unreachable. A perfect continence [Vaizey score of zero] was reported after seven out of 38 procedures [18.4%], while none of the patients reported a perfect continence at baseline. An improved postoperative continence was reported after 18 out of 38 procedures [52.9% after LIFT and 42.9% after AF], a decreased continence after seven procedures [11.8% LIFT and 23.8% AF] and an unchanged continence after 13 procedures [35.3% LIFT and 33.3% AF]. The average change in Vaizey score after procedures with an improved postoperative continence was 4.3 [postoperative 4.0 − preoperative 8.3]. The global change question was correlated to the change in the Vaizey score [r = 0.64], and the MID for a clinically relevant increase in the Vaizey score was calculated to be 2.9 points. A clinically relevant deteriorated continence was found after five procedures, all after AF [25.0%].

3.6. Complications

In total, four complications occurred within 90 days after surgery, none after LIFT and four [19.0%] after AF [p = 0.108]. Complications were [recurrent] abscess formation [n = 3] and continuing rectal blood loss [n = 1]. Two of the three [recurrent] abscesses required a re-intervention.

4. Discussion

The results of this retrospective cohort study show satisfactory clinical healing rates after the LIFT and AF procedures [89.5% and 60.0%, respectively] in patients with Crohn’s perianal fistulas. However, a discrepancy between clinical and radiological healing rates was found. Furthermore, the current data suggest improved clinical and radiological healing rates under anti-TNF and/or immunomodulators. This trend was seen particularly after the AF procedure. Interestingly, the overall continence measured by the Vaizey score improved in almost half of the patients, with an unchanged continence in 34%.

The trend in the AF group towards higher clinical healing percentages after anti-TNF/immunomodulator use seems intuitive, as the success of the mucosal flap is more likely to be related to mucosal inflammation, whereas this might not be relevant for the intersphincteric LIFT procedure. Two recent studies demonstrated that higher serum concentrations of biologicals are essential to improve fistula healing in Crohn’s disease.20 Unfortunately, few serum concentrations were available in this retrospective study, and no conclusion can be drawn whether higher serum concentrations are also beneficial in surgical fistula closure.

MRI is a reliable imaging technique to confirm healing of perianal fistulas. The most efficient way to interpret MRI findings, however, remains of debate. In this retrospective study, we used only the report of the radiologist. Recurrences can also be measured with MRI, but in this study [recurrence of] symptoms were the most commonly reported and also used to measure recurrence. Kamiński et al.12 previously described that recurrences after LIFT are most frequently seen within 12 months, so it is expected that this retrospective study will have identified most recurrences. However, fistula tracts after the LIFT procedure often transform into an intersphincteric fistula tract, which should be taken into account because this reduces the complexity of the fistula and improves the chance of fistula closure in the future.

Symptoms of incontinence are often reported before as well as after surgery. Preservation of the sphincter function is suggested to be better after LIFT for high perianal fistulas in general.9 Our results indeed suggest that the number of patients with improved postoperative continence was higher after LIFT compared to AF. This is an important finding and is in line with the results of a recently published systematic review by Stellingwerf et al.,11 which showed higher incontinence rates after AF compared to LIFT [7.8% vs 1.6%]. Higher incontinence rates after AF might be explained by stretch injury of the anal sphincter and differences in flap thickness.21 Interestingly, most fistula studies are retrospective series, only analysing postoperative incontinence rates. This study also included a pre-operative Vaizey score, and a global change question to determine subjectively whether the patient’s continence had improved, remained unchanged or deteriorated since the surgical procedure. In this way, it could be demonstrated for the first time that almost half of the patients actually benefitted from surgical intervention with respect to continence, and in 34% incontinence was clinically unaffected by the procedure. This might have a positive effect on the reluctance that is sometimes seen with patients and doctors to go for surgical closure in Crohn’s fistulas.

One of the limitations of this study is the small number of included patients, causing a lack of adequate power to find statistically significant differences. Also, the retrospective design has its inherent shortcomings with possible interobserver variability in the assessment of clinical and radiological healing. In addition, the data on continence might be difficult to interpret. The measurements might be affected by the overlap with a loss of faeces through a recurrent or persisting fistula. To minimize interindividual differences, data on incontinence for gas, liquid and solid stools, and soiling were pooled. Furthermore, the Vaizey questionnaire was used to more objectively assess the complaints of incontinence. However, this questionnaire was also of retrospective nature, which could result in recall bias. An attempt was made to minimize this by asking the patients to recall their condition as best as they could for the period just before and after surgery, and by use of a global change score which might better reflect the overall postoperative result.

In interpretating the results it should also be borne in mind that the LIFT AF procedures are not interchangeable. The LIFT procedure is more appropriate for low internal fistula openings, as pulling down the mucosa during the AF procedure could result in a ‘wet anus’. On the other hand, the LIFT procedure could have a higher risk of damaging the anal sphincters depending on the shape and length of the fistula tract [specifically u-shaped with a high mid-tract section], and in those cases the AF procedure might be more appropriate. This study was intended as a retrospective case series, in which the purpose was not to compare the LIFT and AF procedures, but to present the results side by side and see whether predictive factors could be identified. Thus, the findings of this study are essential for gaining a better understanding of the effectiveness of both procedures in this specific patient population. Possible factors associated with the postoperative outcomes such as patient age, smoking and medication use as well as differences in quality of life should be further addressed in larger [prospective] studies. Additionally, the ongoing PISA trial22 will elaborate on the best treatment option for Crohn’s perianal fistulas, comparing medical therapy to surgical closure in a randomized trial.

Conference: This paper has been presented during the meeting of the European Society of Coloproctology [September 2018, Nice], and during the meeting of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [March 2019, Copenhagen]

Funding

This work wasnot financially supported.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

E.M.v.P., M.E.S.: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted. J.D.W.v.B.: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted. K.B.G., W.A.B.: conception and design of the study, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted. C.J.B.: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted.

References

- 1. Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, et al.. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology 2002;122:875–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. ECCO Crohn’s Disease (CD) Consensus Update (2016)2001. [Available from: https://www.ecco-ibd.eu/publications/ecco-guidelines-science/published-ecco-guidelines.html.

- 3. Lee MJ, Parker CE, Taylor SR, et al. Efficacy of medical therapies for fistulizing crohn’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1879–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strik A, Löwenberg M, Ponsioen C, et al. Higher anti-TNF serum levels are associated with perianal fistula closure in Crohn’s disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 2019;54:453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cornillie F, Hanauer SB, Diamond RH, et al.. Postinduction serum infliximab trough level and decrease of C-reactive protein level are associated with durable sustained response to infliximab: a retrospective analysis of the ACCENT I trial. Gut 2014;63:1721–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yarur AJ, Kanagala V, Stein DJ, et al.. Higher infliximab trough levels are associated with perianal fistula healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:933–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crowell KT, Tinsley A, Williams ED, et al.. Vedolizumab as a rescue therapy for patients with medically refractory Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis 2018;20:905–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Christoforidis D, Pieh MC, Madoff RD, Mellgren AF. Treatment of transsphincteric anal fistulas by endorectal advancement flap or collagen fistula plug: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Praag EM, Buskens CJ. The LIFT procedure for a perianal Crohn’s fistula—a video vignette. Colorectal Dis 2019;21:853–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buchanan GN, Halligan S, Bartram CI, Williams AB, Tarroni D, Cohen CR. Clinical examination, endosonography, and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of fistula in ano: comparison with outcome-based reference standard. Radiology 2004;233:674–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stellingwerf ME, van Praag EM, Tozer PJ, Bemelman WA, Buskens CJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of endorectal advancement flap and ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for cryptoglandular and Crohn’s high perianal fistulas. BJS Open 2019;3:231–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kamiński JP, Zaghiyan K, Fleshner P. Increasing experience of ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for patients with Crohn’s disease: what have we learned? Colorectal Dis 2017;19:750–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut 1999;44:77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rojanasakul A. LIFT procedure: a simplified technique for fistula-in-ano. Tech Coloproctol 2009;13:237–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shanwani A, Nor AM, Amri N. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT): a sphincter-saving technique for fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aboulian A, Kaji AH, Kumar RR. Early result of ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:289–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg 1976;63:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Koperen PJ, Wind J, Bemelman WA, Bakx R, Reitsma JB, Slors JF. Long-term functional outcome and risk factors for recurrence after surgical treatment for low and high perianal fistulas of cryptoglandular origin. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:1475–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD, Polly DW Jr, Schuler TC. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J 2007;7:541–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Strik AS, Bots SJ, D’Haens G, Löwenberg M. Optimization of anti-TNF therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2016;9:429–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soltani A, Kaiser AM. Endorectal advancement flap for cryptoglandular or Crohn’s fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:486–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Groof EJ, Buskens CJ, Ponsioen CY, et al.. Multimodal treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: seton versus anti-TNF versus advancement plasty (PISA): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]