Abstract

Purpose of the review

Genome instability has long been implicated as a primary causal factor in cancer and diseases of aging. The genome is constantly under attack from extrinsic and intrinsic damaging agents. Uracil misincorporation in DNA and its repair is an intrinsic factor resulting in genomic instability and DNA mutations. Additionally, the presence of uracil in DNA can modify gene expression by interfering with promoter binding and transcription inhibition or upregulation of apoptotic proteins. In immune cells, uracil in DNA drives beneficial genomic diversity for antigen driven immunity. This review addresses diseases that are linked to uracil accumulation in DNA, its causes, consequences and the associated biomarkers of risk factors.

Recent findings

Elevated genomic uracil is associated with megaloblastic anemia, neural tube defects and retroviral immunity. Current evidence supporting causal mechanisms and nutritional interventions that rescue impaired pathways associated with uracil accumulation in DNA are summarized in this review.

Summary

Nutritional deficiencies in B-vitamins can cause uracil misincorporation into DNA leading to genome instability and associated pathologies. Nutritional approaches to preventing uracil accumulation in DNA show some promise to address its associated pathologies, but additional randomized controlled trials are needed.

Keywords: uracil in DNA, de novo thymidylate synthesis, megaloblastic anemia, neural tube defects, apoptosis, genomic instability

I. Introduction

The genome is constantly exposed to endogenous and exogenous factors that can cause damage. These agents induce chemical modifications of nucleotides and DNA strand breaks. As a result, mutations accumulate, genome instability and/or stalled DNA replication forks, which can cause cell death (1). Approximately 104-105 DNA lesions/day are generated in mammalian genome because of endogenous spontaneous hydrolytic decay (2). DNA repair mechanisms have evolved for efficient monitoring and maintenance of genomic integrity of an organism. If unrepaired, genomic instability impairs physiological processes with increased risk cancer and accelerated ageing (3,4). Epigenetic modifications, environmental exposures and nutrition deficiencies are critical factors that compromise genome integrity and cause disease (5). Uracil is commonly found in the genome of all organisms. It originates from two independent processes: cytosine deamination and dUTP misincorporation. Uracil is naturally identified and removed by DNA-repair enzymes. However, excessive accumulation of uracil in DNA and repair can result in DNA strand breaks and lead to p53 or PARP-1 mediated apoptosis. This review focusses on the factors affecting uracil accumulation in DNA and explores the consequent associated clinical disorders including megaloblastic anemia, neural tube defects and HIV immunity.

II. Factors affecting uracil accumulation in DNA

Uracil accumulation in DNA varies widely across different species and cell types. The lack of uniform and standardized analytical methods for determining uracil levels in DNA creates limitations in comparing across the studies performed to date (6,7).

A. Cytosine deamination

Cytosine deamination can be spontaneous or enzyme-mediated resulting in U:G mispairing. If unrepaired, it leads to a C:G → A:T transition mutation. Cytosine deamination is a major source of spontaneous mutations in the genome (8). An estimated 400 uracil bases/genome/day are formed in humans from cytosine deaminations. In actively replicating human cells, this value increases to 2000 uracil bases/genome/day (9). The rate of uracil incorporation is higher in transcriptionally active regions of genome and rapidly dividing cells. Variation in this rate arises because of differential rates of enzymatic deamination for single and double stranded DNA. Enzymatic deaminations are catalyzed by cytosine deaminase (AID) and apolipoproteinB-editing complex catalytic subunit1 (APOBEC1). AID activity introduces mutations and genomic diversity in antibody synthesis by inducing uracil accumulation in DNA. APOBEC1 catalyzes cytosine deamination in both DNA and RNA (10). Activity of these enzymes and uracil accumulation may also induce C → T transition mutations, increasing risk for cancer. In immune cells, cytosine deamination influences antigen-driven generation and diversification of antibodies via class switch recombination (CSR) and somatic hypermutation (11). However, in tumor cells, uncontrolled expression of cytosine deaminases leading to DNA deamination was observed. Hence, C→T transition mutations are a common signature in most types of cancer. Additionally, impairment of the base excision repair (BER) enzyme, uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG/UNG) was observed in case of immunoglobulin CSR hyper IgM syndrome (12).

B. Uracil (dUTP) misincorporation in DNA

Another source of uracil in DNA results from the misincorporation of dUTP in lieu of dTTP during DNA synthesis. This generates non-mutagenic U:A pairs. DNA polymerases are unable to effectively discriminate between dUTP and dTTP during DNA synthesis, and therefore rates of uracil misincorporation are influenced by the cellular dUTP/dTTP ratio. The steady-state level of mammalian genomic uracil is unknown. It has been estimated, based on calculations on the relative sizes of the substrate dUTP/dTTP pools, that <1 dUMP enters DNA per 105 dTMP in normal human lymphoblasts. Due to excision and repair, the number drops to 10–15 uracil residues per diploid genome (13).

The dUTP/dTTP ratio is regulated by three major processes: the de novo dTMP biosynthesis pathway, the salvage dTMP synthesis pathway and activity of dUTPase. The de novo dTMP biosynthesis pathway is a part of the folate-mediated one carbon metabolic (FOCM) network and responsible for the conversion of dUTP to dTTP catalyzed by thymidylate synthase (Tyms). Folate and vitamin B12 deficiency disrupt de novo dTMP biosynthesis resulting in elevated DNA uracil levels in blood and bone marrow cells (14). The salvage pathway involves conversion of thymidine to dTMP catalyzed by thymidylate kinase. In the case of disrupted de novo pathway, tissues specific salvage pathway can contribute to maintain the dTMP levels.

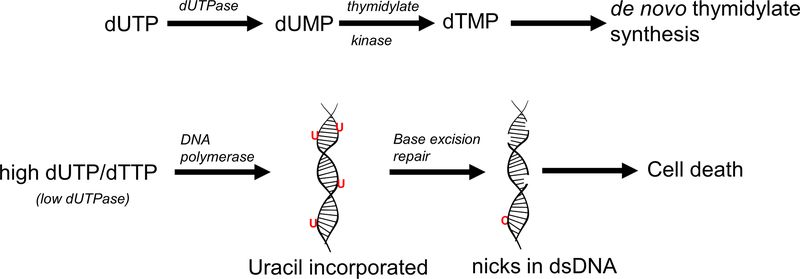

The third factor affecting uracil misincorporation into DNA is dUTPase (Figure 1), which catalyzes the conversion of dUTP to dUMP (15). This reaction maintains DNA integrity by two mechanisms: a) it provides dUMP, a substrate for Tyms and b) catabolizes dUTP to maintain a favorable dUTP/dTTP ratio. Under high dUTP concentrations, the rate of uracil misincorporation into DNA increases. Excessive removal of uracil from the DNA by UNG results in strand breaks. Consequently, under high BER activities, p53-mediated apoptosis is signalled.

Figure 1.

Uracil accumulation in DNA

The top schematic shows the conversion of dUTP to dUMP by dUTPase. dTTP is synthesized from either dUMP via de novo thymidylate biosynthesis pathway or from thymidine via the salvage pathway. The bottom schematic represents the reactions during an elevated dUTP/dTTP and low dUTPase activity. High dUTP results in an elevated rate of uracil incorporation into DNA by DNA polymerase. Uracil is excised under action of BER. Excessive excision and repair of uracil leads to chromosomal fragmentation and cell death.

From clinical perspective, studies of dUTPase knockdown and silencing experiments reveal dual role of the enzyme. In cancer therapies, silencing dUTPase resulted in halting proliferation in malignant cells (9). In another study, dUTPase knockdown in pancreatic β-cells resulted in cellular apoptosis and diabetes. Tight regulation of genomic uracil by dUTPase is important for normal hematopoiesis and insulin production. The absence of dUTPase activity can result in megaloblastic anemia and a novel form of monogenic diabetes associated with bone marrow failure (16). Inhibitors of dUTPase in chemotherapy have been investigated for cancer treatment in human clinical trials (17).

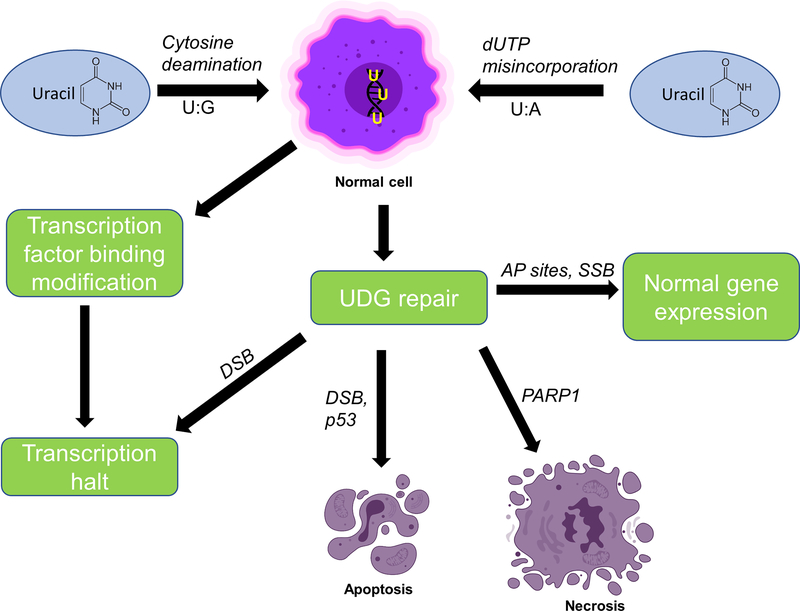

III. DNA damage repair from uracil miscincorporation

Uracil incorporation into DNA is not mutagenic but can influence genome stability. BER enzymes recognize and repair A:U base pairs and excise uracil-containing oligonucleotides, generating abasic sites in DNA and subsequent single strand breaks (SSB). If a high level of SSBs form through BER, DNA double strand breaks (DSB) and chromosomal instability can ensue. The abasic AP sites can also signal transcription stalling. Elevated uracil incorporation lowers promoter binding affinity for human T7-RNApol II, inhibiting transcription (18). On the other hand, the DSB’s can cause mutations during non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) process (Figure 2). The balance between high frequency uracil excision and cellular tolerance and DNA-damage induced apoptosis remain unclear. Folate deficiency is identified as a major factor affecting DNA strand breaks and chromosomal breakage.

Figure 2.

Fate of genomic uracil

Uracil is incorporated in DNA via two processes: cytosine deamination (generates U:G pair) or dUTP misincorporation (generate U:A pair). Cytosine deamination results in accumulation of mutations and may signal transcription halt. dUTP misincorporation activates UDG mediated DNA repair. This induces single strand breaks (SSBs) in DNA and generates abasic AP sites. The repair process naturally occurs in cells and results in normal gene expression. Excessive UDG repair causes DNA double strand breaks (DSB) and activate p53 or PARP1 apoptotic proteins. It ultimately results in apoptosis or necrosis.

IV. Consequence of uracil in DNA and human diseases

Uracil misincorporation results in DNA damage and ultimately cell death that leads to specific pathological conditions including megaloblastic anemia, folate responsive NTDs and retroviral immunity which are reviewed below.

A. Megaloblastic anemia

Megaloblastic anemia (Mba) refers to a heterogeneous group of anemias characterized by the presence of abnormally large pre-erythroblasts in the bone marrow, called megaloblasts. The primary causes of Mba are impaired DNA replication and cytokinesis. In erythroblasts, RNA-dependent cytoplasmic maturation remains unaffected. Differential maturation rates of impaired DNA replication in the nucleus, without effets on cytoplasm maturation, in cell division results in abnormally large megaloblasts. In erythroblasts, impaired hematopoiesis resulting from B-vitamin (folate and cobalamin) deficiencies is the primary cause of Mba. As a result, FOCM, de novo thymidylate synthesis and the methylation of cytosine bases in DNA are disrupted. Consequently, erythroblasts have elevated rates of genomic uracil misincorporation and repair. This in-turn triggers p53/p21 mediated apoptosis (19,20). Also, deleterious mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase (Dhfr), an enzyme that participates in dTTP synthesis, and antifolate treatments that target Dhfr, have been reported to be associated with Mba (7). In addition to folate deficiency, Mba is also linked to inhibitory mutations in the gene encoding uridine monophosphate synthase, causing dUMP deficiencies. Thus, synthesis of dTMP is also disrupted, resulting in a dNTP imbalance. In summary, B-vitamin mediated one carbon metabolism and pyrimidine biosynthetic pathways are crucial for maintaining genomic stability. Any disruption in these pathways can result in abnormal uracil accumulation resulting in DNA damage and cell death. The existing therapies for Mba predominantly involve nutritional supplementation with B-vitamins and use of inhibitors of MTHFR (21,22).

B. Neural tube defects

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are birth defects resulting from the failure to close the neural tube in spine or cranium during early stages of development. It occurs due to insufficient proliferation of the neural epithelium and/or increased rates of apoptosis. Folate deficiency is one of the primary causes of NTDs. Also, chemotherapeutic drug Methotrexate, a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor, increases embryonic NTD incidence (23). The enzyme serine hydroxymethyl transferase (Shmt) provides folate-activated one carbon unit required for de novo dTMP synthesis. The Shmt1+/− mouse model exhibits folic acid-responsive NTDs and impaired de novo dTMP synthesis. Elevated uracil in nuclear DNA is the only biomarker that correlates with incidence of NTDs (24). Folate supplementation in the maternal diet prevented NTDs, presumably by providing more substrate for the Tyms catalysed synthesis of dTMP (25). These and other studies indicate that disrupted de novo dTMP synthesis pathway and uracil accumulation in DNA underlies the pathogenesis of NTD in mouse models.

Dietary nucleotide supplementation in pregnant mice can both prevent or increase rates of NTD-affected pregnancies. For the Shmt1+/− mouse model, supplementation of the maternal diet with dietary nucleosides thymidine, uridine or deoxyuradine affected serum folate levels (25). Supplementation of maternal diet with uridine increased NTD incidence, while deoxyuridine rescued NTDs when fed a folate-deficient diet. Hence, it is advisable for women of reproductive age to avoid over-the-counter dietary uridine supplements to avoid impaired embryonic development (25).

C. HIV DNA benefits from genomic uracil

In the absence of proof-reading activity, HIV reverse transcriptase (RTase) cannot differentiate between dUTP and dTTP during replication. HIV transcripts in human immune cells are heavily uracilyated (tolerate >500 uracil/10kb genome). Uracil in the HIV genome originates from cytosine deamination through Apobec3 activity, which is overexpressed in human immune cells. The HIV genome does not encode dUTPase and UNG enzymes for uracil repair, but rather relies on the host enzymes. The virulence of HIV is reported to be independent of UNG activity associated with virions or macrophages (26). All these tools have evolved to facilitate early phases of viral replication cycles.

During replication, the activated ends of the viral genome may attack and integrate into itself via the suicidal autointegration pathway. The uracil-rich immune cells (macrophage and T cells) and viral genome inhibit autointegration processes and facilitate chromosomal integration. Structural and enzymatic analysis into the uracilated viral-DNA and HIV Integrase enzyme activity reveal that uracil misincorporation into viral DNA triggers genomic instability by inducing DNA strand breaks. This mechanism blocks Integrase-mediated strand transfer (leading to autointegration) and favors chromosomal DNA integration of viral genome (27). Additionally, in monocyte-derived macrophages, low UDG activity facilitates viral genome integration (28). In another mechanism, uracil accumulation in HIV-DNA interferes with the cytosolic DNA sensor in immune cells that can identify foreign viral DNA and trigger interferon production. This allows HIV to deactivate innate immunity and promote its survival.

Uracil accumulation also provides insights into the difficult challenges associated with retroviral therapies. The rapidly replicating viral genome in the cytosol has a greater uracil load than slow-replicating nuclear genome. Enhanced UDG activity in tandem with inhibited dUTPase allows host-BER to excise the viral genome more rapidly. Human dUTPase inhibitors have been used successfully to enhance anti-tumor effects of Tyms inhibitors and can potentially provide protection to CD4+T cells from viral genome infection (28,29).

V. Conclusion

Uracil accumulation in DNA is a normal event that can cause and/or accelerate human pathologies. It is associated with megaloblastic anemia and embryonic neural tube defects resulting from impaired de novo thymidylate synthesis. It is not fully established if the cause of these disorders is uracil accumulation in nuclear DNA and DNA damage, or the associated alterations in DNA replication rates and/or transcriptional effects. Interventions that target uracil-related human pathologies include: a) introducing dietary interventions that can rescue impaired metabolic pathways and limit steady state genomic uracil concentrations and b) identifying potential drug targets for deoxyuracil nucleotide-associated pathways and enzymes.

There are many questions regarding the presence of uracil in DNA. Are the pathogenic effects due to a transcription signal, decreased rates of DNA replication or due to induction of DNA instability? What is the tolerance level of genomic uracil before apoptosis is signalled? These questions are to understanding many DNA repair deficiency syndromes and subsequently for developing treatment strategies for the associated diseases.

Key Points.

Deoxyuracil incorporation into DNA occurs due to cytosine deamination and dUTP misincorporation.

In adaptive immunity, uracilation brings about genetic diversity.

Uracil incorporation into DNA is observed in megaloblastic anemia, neural tube defects, and HIV immunity.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support and Sponsorship: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R37DK58144 to Patrick J. Stover.

Abbreviations

- dNTP

deoxynucleotide triphosphate

- dUTP

deoxyuridine triphosphate

- dUMP

deoxyuridine monophosphate

- dTTP

deoxythymidine triphosphate

- dTMP

deoxythymidine monophosphate

- DHFR

dihydrofolate reductase

- MTHFR

methyl tetrahydrofolate reductase

- SHMT

serine hydroxymethyl transferase

- Apobec3

apolipoproteinB editing complex catalytic subunit 3

- FOCM

folate mediated one carbon metabolism

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Sidorova J A game of substrates: replication fork remodeling and its roles in genome stability and chemo-resistance. Cell Stress. 2017. December 11;1(3):115–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiwari V, Wilson DM. DNA Damage and Associated DNA Repair Defects in Disease and Premature Aging. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105(2):237–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terabayashi T, Hanada K. Genome instability syndromes caused by impaired DNA repair and aberrant DNA damage responses. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2018;34(5):337–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gizem Sonugür F, Akbulut H. The role of tumor microenvironment in genomic instability of malignant tumors. Front Genet. 2019;10(1063):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladeira C, Carolino E, Gomes MC, Brito M. Role of Macronutrients and Micronutrients in DNA Damage: Results From a Food Frequency Questionnaire. Nutr Metab Insights. 2017;10:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chon J, Stover PJ, Field MS. Targeting nuclear thymidylate biosynthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 2017;53:48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chon J, Field MS, Stover PJ. Deoxyuracil in DNA and disease: Genomic signal or managed situation? DNA Repair (Amst). 2019;77(May 2019):36–44.*An overall review provides detailed mechanistic insights about deoxyuracil in DNA and its effects.This review provides first insight into using dUTPase as a gene therapy target.

- 8.Lewis CA, Crayle J, Zhou S, Swanstrom R, Wolfenden R. Cytosine deamination and the precipitous decline of spontaneous mutation during Earth’s history. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(29):8194–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Studebaker AW, Lafuse WP, Kloesel R, Williams M V. Modulation of human dUTPase using small interfering RNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327(1):306–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grünewald J, Zhou R, Garcia SP, Iyer S, Lareau CA, Aryee MJ, et al. Transcriptome-wide off-target RNA editing induced by CRISPR-guided DNA base editors Vol. 569, Nature. Nature Publishing Group; 2019. p. 433–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu K, Lieber MR. Current insights into the mechanism of mammalian immunoglobulin class switch recombination. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;54(4):333–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poulos RC, Olivier J, Wong JWH. The interaction between cytosine methylation and processes of DNA replication and repair shape the mutational landscape of cancer genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(13):7786–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fadda E, Poms R. On the molecular basis of uracil recognition in DNA: Comparative study of T-A versus U-A structure, dynamics and open base pair kinetics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(2):767–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paone A, Marani M, Fiascarelli A, Rinaldo S, Giardina G, Contestabile R, et al. SHMT1 knockdown induces apoptosis in lung cancer cells by causing uracil misincorporation. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(11):e1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirmondo R, Lopata A, Suranyi EV, Vertessy BG, Toth J. Differential control of dNTP biosynthesis and genome integrity maintenance by the dUTPase superfamily enzymes. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dos Santos RS, Daures M, Philippi A, Romero S, Marselli L, Marchetti P, et al. DUTPase (DUT) Is mutated in a novel monogenic syndrome with diabetes and bone marrow failure. Diabetes. 2017;66(4):1086–93.**This is the first review report of uracil regulation (dUTPase knockdown) to megaloblastic anemia and discovery of novel monogenic diabetes.

- 17.Saito K, Nagashima H, Noguchi K, Yoshisue K, Yokogawa T, Matsushima E, et al. First-in-human, phase I dose-escalation study of single and multiple doses of a first-in-class enhancer of fluoropyrimidines, a dUTPase inhibitor (TAS-114) in healthy male volunteers. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73(3):577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui J, Gizzi A, Stivers JT. Deoxyuridine in DNA has an inhibitory and promutagenic effect on RNA transcription by diverse RNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(8):4153–68.**This is a detailed review of deoxyuracil in DNA effects at a transcriptional signal.

- 19.Yadav MK, Manoli NM, Madhunapantula S V. Comparative assessment of vitamin-B12, folic acid and homocysteine levels in relation to p53 expression in megaloblastic anemia. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wickramasinghe SN, Fida S. Bone marrow cells from vitamin B12- and folate-deficient patients misincorporate uracil into DNA. Blood. 1994;83(6):1656–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Field MS, Kamynina E, Watkins D, Rosenblatt DS, Stover PJ. Human mutations in methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 impair nuclear de novo thymidylate biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(2):400–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green R, Datta Mitra A. Megaloblastic Anemias: Nutritional and Other Causes. Vol. 101, Medical Clinics of North America. 2017. p. 297–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Guan Z, Chen Y, Dong Y, Niu Y, Wang J, et al. Genomic DNA Hypomethylation Is Associated with Neural Tube Defects Induced by Methotrexate Inhibition of Folate Metabolism. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaudin AE, Abarinov E V, Noden DM, Perry CA, Chu S, Stabler SP, et al. Shmt1 and de novo thymidylate biosynthesis underlie folate-responsive neural tube defects in mice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(1):789–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martiniova L, Field MS, Finkelstein JL, Perry CA, Stover PJ. Maternal dietary uridine causes, and deoxyuridine prevents, neural tube closure defects in a mouse model of folate-responsive neural tube defects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(4):860–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson ME, Harris RS, Harki DA. APOBEC Enzymes as Targets for Virus and Cancer Therapy. Cell Chem Biol. 2018;25(1):36–49.*This study discusses the domain of cytosine deaminase enzymes as a potential target for genetherapy for HIV treatments.

- 27.Yan N, O’Day E, Wheeler LA, Engelman A, Lieberman J. HIV DNA is heavily uracilated, which protects it from autointegration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(22):9244–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weil AF, Ghosh D, Zhou Y, Seiple L, Moira AM, Spivak AM, et al. Uracil DNA glycosylase initiates degradation of HIV-1 cDNA containing misincorporated dUTP and prevents viral integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(6):E448–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kara H, Chazal N, Bouaziz S. Is Uracil-DNA Glycosylase UNG2 a New Cellular Weapon Against HIV-1? Curr HIV Res 2019;17(3):148–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]