Introduction

Problematic opioid use and subsequent adverse consequences, including opioid-related overdose deaths, are well-documented public health concerns in the United States (US) impacting adults and youth alike. Emerging data indicate that any exposure to opioids as an adolescent (medical or non-medical) appears to present short and long term risks for initiating heroin and prescription opioid use [6,29,36,51]. In 2016, approximately 3.6% of adolescents (12 to 17 years) and 7.3% of young adults (18 to 25 years) reported current misuse of prescription opioids and it is estimated that 0.6% of adolescents and 1.1% of young adults had an opioid use disorder [49]. Further, in recent decades, pediatric inpatient admissions due to opioid poisoning and deaths from prescription drug overdoses doubled [4,15]. While leftover prescriptions are repeatedly identified as a primary source for nonmedical use in adolescents [3,30,52], opioids remain a standard part of pediatric pain management [19,54]. Dramatic increases in opioid prescribing to adults have been tied to increases in opioid-related mortality [26,46,53]; however, results from national studies examining opioid prescribing rates to youth in the last two decades vary, with some data indicating little to no significant change [19], while others report increases of 40%−100% [14,28,47]. These conflicting estimates make it challenging to determine relations between opioid prescribing rates and adverse outcomes.

Regarding individual factors associated with receiving an opioid prescription in childhood and adolescence, available data suggest that ethnic minority youth are less likely to receive opioid prescriptions [19,37,44,56], despite reporting pain of greater intensities than Caucasian youth [37,44,56]. Other data indicate that youth who are older [19], have a preexisting mental health diagnosis [40,55], or multiple pain complaints [39] are more likely to receive an opioid or misuse opioids. Research has not found significant differences in opioid prescribing rates to youth based on sex, although in non-clinical populations, adolescent males are more likely than females to engage in non-medical opioid use [35] and have higher rates of drug overdose-related death [9]. Unlike adult populations where several studies suggest associations between chronic opioid use and increased distress, disability, opioid misuse and adverse outcomes [7,13,20,24,27]; it is unknown if opioid prescription frequency may influence health-related outcomes in youth.

The current study examined data from the electronic medical records system of the primary University hospital in New Mexico (NM) for all youth age 21 and under who received at least one outpatient opioid prescription between 2005 and 2016. NM’s consistently high rates of drug-induced deaths [34] and opioid misuse in youth [50] justified closer examination of state level prescribing trends to elucidate relations between prescribing rates and adverse outcomes as well as inform prescribing practices within the hospital system. The primary aim was to quantify trends in prescription of opioids to youth from 2005 to 2016. The secondary aims were to: 1) identify individual factors associated with receiving single or multiple prescriptions, and 2) examine frequency of markers of morbidity (e.g., overdose) and mortality after receiving an opioid prescription, as well as factors associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes.

Methodology

Setting and Data Source

Pre-existing data was extracted from the electronic medical records system at the University of New Mexico Hospital (UNMH). The hospital is located in an urban area, serves as NM’s only Level 1 trauma center, and is the state’s primary site of pediatric specialty care. Data were extracted and de-identified using the services of the UNMH’s Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC). The CTSC acted as an “honest broker” to evaluate patients in relation to stated inclusion criteria, extract the requested variables from the electronic health record (EHR), and de-identify patient health information to safeguard confidentiality. The UNMH EHR was established in 2005, thus, data extraction dates were from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2016. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained to perform the data extraction and planned analyses detailed below (Study approval ID: 16–123).

Measures

Inclusion criteria along with extracted variables in the dataset are presented in Table 1 and summarized below. Only encounters with opioid prescription dates within the study time frame were extracted and included.

Table 1.

Variables extracted from patient electronic medical records

|

Inclusion criteria: Age 0–21, Prescribed an opioid during an outpatient encounter (e.g. Emergency Department, discharge from an inpatient admission, day surgery, or outpatient clinic) Exclusion criteria: Inpatient opioid prescription encounters | ||

| Variables of interest | ||

|

Individual/ baseline Data extracted once for each patient |

Opioid prescription encounter

Data extracted from each encounter where an opioid was prescribed |

Adverse outcomes

Data extracted from each clinical encounter for 12 months following first or last prescription |

| Age | Medication-related characteristics: | Markers of morbidity |

| Sex | Encounter location | Overdose (admission, ED encounter) |

| Ethnicity | Name of drug | Medication-Assisted Treatment |

| Race | Prescribed dose | Death |

| Primary language | Duration/ dispense value | Subsequent diagnoses |

| Payer status | Total # of opioid prescriptions | |

| Non-opioid prescriptions | Active diagnoses | |

| Other pain medications | ||

| Psychiatric medications | ||

| Premorbid diagnoses | ||

Note. An “encounter” is defined as a unique clinical instance of direct provider to patient interaction; Payer status= Public/ Government Assistance (e.g. Medicaid), Private, or Uninsured; Encounter location= Emergency, discharge from inpatient, outpatient, or day surgery; Diagnoses will also coded as Acute, Chronic pain, Mental Health, Other Co-Morbid Condition, or Cancer Related; Prescribed dose will be converted to Morphine Equivalent Dose.

Sample included patients age 0 to 21 years who received an outpatient prescription for an opioid between 2005 and 2016. Inpatient opioid prescriptions were excluded, although prescriptions received at discharge from inpatient stays were included.

Baseline demographic factors include relevant descriptive medical and psychosocial characteristics. These were age at first prescription encounter, race, ethnicity, and insurance payer status.

Opioid prescription variables were extracted for each outpatient visit where an opioid was prescribed in order to characterize aspects of the prescription and encounter (e.g., encounter location, diagnoses). Type of opioid prescription was classified based on the active opioid agonist agent (e.g., oxycodone and acetaminophen/oxycodone were both classified as “oxycodone”): Oxycodone, Hydrocodone, Codeine, Tramadol, Morphine, Fentanyl, and Other (i.e., meperidine, opium products). Individuals who only received prescriptions for opioids that can be used both for medication-assisted treatment of an opioid use disorder and pain management (e.g., Methadone, Suboxone) were excluded, since the data did not reliably discern the indication for the prescription.

The total number of opioid prescriptions received by each individual over the course of the study timeframe was tallied to derive the total number of prescriptions. Furthermore, two variables were created to examine frequency of opioid prescription. The first was a binary variable (i.e., single prescription vs. multiple prescription) and the second was a categorical variable (i.e., 1, 2, 3, or 4+ prescriptions).

Outcomes variables were defined as markers of morbidity and mortality. These markers included overdose and receipt of a prescription for medication-assisted treatment, as well as death.

Variable Extraction and Coding Methodology

Each case was assigned a unique ID number, which was used to link each prescription encounter. Frequency of opioid prescriptions across the study time frame was calculated for each patient into a “total opioid prescriptions” variable. Patient age at first opioid prescription was calculated in years. Age at baseline was categorized into early childhood (0–5 years), school age (6–11 years), adolescent (12–17 years), and young adult (18–21 years). Encounter location was coded as outpatient clinic, emergency, discharge from inpatient, or day surgery. Insurance payer status was coded into three categories: Private/ Commercial, Public/ Government Assistance (e.g., Medicaid), and Uninsured.

To examine outcomes following the patient’s most recent opioid prescription encounter, patients were tracked one year after their last recorded opioid prescription. At each subsequent encounter, we looked for evidence of a prescription for medication-assisted treatment (MAT; e.g., Suboxone) as a proxy for potential development of opioid dependency. The overdose and mortality variables were extracted from the patient’s entire medical history after receipt of an opioid. Additional descriptive variables were extracted for each overdose encounter, including documented substances at overdose, total number of overdoses, and evidence of whether or not the overdose was intentional.

Diagnoses from encounters occurring on October 1, 2015 and later utilized ICD-10 codes, due to a hospital wide transition; diagnoses from encounters prior to that date utilized ICD-9 codes. To integrate ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnoses, coding of ICD-10 chapters and subchapters was based on ICD-9 chapters and subchapters (as the majority of cases had ICD-9 diagnosis), such that each ICD-10 diagnosis was grouped into the related ICD-9 chapter/ subchapter.

Statistical Analysis Plan

Database merging, cleaning, and coding, was conducted using R [38] and analyses were conducted using SPSS v25 [21]. Descriptive statistics and frequencies were calculated for all sociodemographic, medical, medication, and outcome variables. Frequencies across study years were calculated for opioid prescriptions, individuals receiving single versus multiple prescriptions, and markers of morbidity and mortality. Relative risk, including 95% confidence intervals, was calculated for receipt of single versus multiple prescriptions, as well as markers of morbidity and mortality based on individual sociodemographic characteristics

Results

From 2005–2016, 42,020 unique patients age 21 or younger received a total of 71,647 opioid prescriptions. Table 2 provides an overview of annual frequency of opioid prescriptions as well as number of patients receiving single or multiple opioid prescriptions.

Table 2.

Annual sample characteristics including total opioid prescriptions and frequency of individuals receiving single vs. multiple prescriptions

| Year | Total annual opioid prescriptions | Total patients receiving their first opioid prescription* | Total patients who received an opioid prescription** | Patients who received a single opioid prescription | Patients who received multiple opioid prescriptions | % of sample receiving multiple opioid prescriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2470 | 1733 | 1736 | 1345 | 391 | 22.52% |

| 2006 | 5150 | 3431 | 3644 | 2830 | 814 | 22.34% |

| 2007 | 7000 | 4374 | 4864 | 3725 | 1139 | 23.42% |

| 2008 | 7562 | 4439 | 5176 | 3884 | 1292 | 24.96% |

| 2009 | 7487 | 4280 | 5124 | 3847 | 1277 | 24.92% |

| 2010 | 7215 | 4128 | 4980 | 3839 | 1141 | 22.91% |

| 2011 | 6974 | 3940 | 4846 | 3704 | 1142 | 23.57% |

| 2012 | 6295 | 3574 | 4452 | 3443 | 1009 | 22.66% |

| 2013 | 6203 | 3503 | 4337 | 3343 | 994 | 22.92% |

| 2014 | 5736 | 3153 | 3983 | 3081 | 902 | 22.65% |

| 2015 | 4945 | 2777 | 3470 | 2658 | 812 | 23.40% |

| 2016 | 4610 | 2688 | 3387 | 2698 | 689 | 20.34% |

| TOTAL | 71647 | 42020 | 49999 | 38397 | 11602 | 23.20% |

Represents number of unique patient in the dataset.

This includes more patients than in the first column because some individuals received prescriptions in multiple years.

Thus, each patient is counted only once per year, but may show up in multiple years.

Medication and Demographic Characteristics at Receipt of First Opioid (baseline)

Medication Characteristics.

The highest number of individuals received their first opioid prescription in 2008 (n=4,439), in contrast to 2005 when only 1,733 youth received an opioid prescription for the first time (see Table 3). Type of first opioid prescription was most commonly Oxycodone (46.0%, n=19,318) or Hydrocodone (36.5%, n=15,331), while few (<.1%, n=16) received Fentanyl as a first opioid prescription. We were unable to examine dosing information, as only a small percentage of EHR entries (< 20%) contained prescribed dose or amount.

Table 3.

Medication-related and demographic characteristics at receipt of first opioid of patients who received single vs. multiple prescriptions

| Full Sample N= 42,020 |

Single opioid N=28,911 |

Multiple opioid N= 13,109 |

Relative risk for multiple opioids | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | (95% CI) | |

| Year of first prescription | |||||||

| 2005† | 1,733 | 4.1% | 1047 | 3.6% | 686 | 5.2% | REF |

| 2006 | 3,431 | 8.2% | 2182 | 7.5% | 1249 | 9.5% | .92 (.85-.99) |

| 2007 | 4,374 | 10.4% | 2827 | 9.8% | 1547 | 11.8% | .89 (.83-.96) |

| 2008 | 4,439 | 10.6% | 2858 | 9.9% | 1581 | 12.1% | .90 (.84-.97) |

| 2009 | 4,280 | 10.2% | 2807 | 9.7% | 1473 | 11.2% | .87 (.81-.93) |

| 2010 | 4,128 | 9.8% | 2827 | 9.8% | 1301 | 9.9% | .80 (.74-.86) |

| 2011 | 3,940 | 9.4% | 2754 | 9.5% | 1186 | 9.0% | .76 (.71-.82) |

| 2012 | 3,574 | 8.5% | 2543 | 8.8% | 1031 | 7.9% | .73 (.67-.79) |

| 2013 | 3,503 | 8.3% | 2522 | 8.7% | 981 | 7.5% | .71 (.65-.77) |

| 2014 | 3,153 | 7.5% | 2315 | 8.0% | 838 | 6.4% | .67 (.62-.73) |

| 2015 | 2,777 | 6.6% | 2044 | 7.1% | 733 | 5.6% | .67 (.61-.73) |

| 2016 | 2,688 | 6.5% | 2185 | 7.6% | 503 | 3.8% | .47 (.43-.52) |

| Total opioid prescriptions | |||||||

| 1 | 28,911 | 68.8% | 28,911 | 100% | -- | -- | -- |

| 2 | 7,460 | 17.8% | -- | -- | 7,460 | 56.9% | -- |

| 3 | 2,734 | 6.5% | -- | -- | 2,734 | 20.9% | -- |

| 4 or more | 2,915 | 6.9% | -- | -- | 2,915 | 22.2% | -- |

| First opioid prescription type | |||||||

| Oxycodone† | 19,318 | 46.0% | 12547 | 43.4% | 6771 | 51.6% | REF |

| Hydrocodone | 15,331 | 36.5% | 11120 | 38.5% | 4211 | 32.1% | .78 (.76-.81) |

| Codeine | 6,907 | 16.4% | 5006 | 17.3% | 1901 | 14.5% | .79 (.75-.82) |

| Tramadol | 253 | 0.6% | 154 | 0.5% | 99 | 0.8% | 1.12 (.96–1.30) |

| Morphine | 150 | 0.4% | 57 | 0.2% | 93 | 0.7% | 1.77 (1.56–2.01) |

| Fentanyl | 16 | <.1% | 6 | 0.02% | 10 | 0.01% | 1.78 (1.22–2.61) |

| Other | 45 | .1% | 21 | 0.1% | 24 | 0.2% | 1.52 (1.16–2.00) |

| Age | |||||||

| Early childhood (0–5 years) † | 7,432 | 17.7% | 5780 | 20.0% | 1652 | 12.6% | REF |

| School age (6–11 years) | 6,790 | 16.2% | 4829 | 16.7% | 1961 | 15.0% | 1.30 (1.23–1.37) |

| Adolescent (12–17 years) | 11,471 | 27.3% | 7240 | 25.0% | 4231 | 32.3% | 1.66 (1.58–1.52) |

| Young-adult (18–21 years) | 16,327 | 38.9% | 11,062 | 38.3% | 5265 | 40.2% | 1.45 (1.38–1.52) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female † | 18,927 | 45.0% | 12,974 | 44.9% | 5,953 | 45.4% | REF |

| Male | 23,093 | 55.0% | 15,937 | 55.1% | 7,156 | 54.6% | .99 (.96–1.01) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Not Hispanic/ Lantinx† | 11,496 | 27.4% | 7618 | 26.3% | 3878 | 29.6% | REF |

| Hispanic/ Lantinx | 21,044 | 50.1% | 14364 | 49.7% | 6681 | 51.0% | .94 (.91-.97) |

| Not reported | 9,480 | 22.5% | 6929 | 24.0% | 2550 | 19.5% | -- |

| Race | |||||||

| White† | 19,985 | 48.3% | 13,239 | 46.5% | 6746 | 52.2% | REF |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4553 | 11.0% | 3144 | 11.0% | 1409 | 10.9% | .92 (.87-.96) |

| Black/African American | 1292 | 3.1% | 835 | 2.9% | 457 | 3.5% | 1.05 (.97–1.13) |

| Two or More Races | 539 | 1.3% | 372 | 1.3% | 167 | 1.3% | .92 (.81–1.04) |

| Asian | 415 | 1.0% | 313 | 1.1% | 102 | 0.8% | .73 (.61-.86) |

| Hawaiian Native/ Pacific Islander | 96 | 0.2% | 65 | 0.2% | 31 | 0.2% | .96 (.72–1.28) |

| Other | 3295 | 8.0% | 2579 | 9.1% | 716 | 5.5% | -- |

| Decline to answer/ unavailable | 11,241 | 27.1% | 7946 | 27.9% | 3295 | 25.5% | -- |

| Primary language | |||||||

| English† | 37,243 | 88.9% | 25,455 | 88.3% | 11,788 | 90.2% | REF |

| Spanish | 3,755 | 8.9% | 2776 | 9.6% | 979 | 7.5% | .82 (.78-.87) |

| Other/ Not reported | 894 | 2.1% | 588 | 2.0% | 306 | 2.3% | -- |

| Encounter type | |||||||

| Outpatient† | 5,401 | 12.9% | 3272 | 11.3% | 2129 | 16.3% | REF |

| Emergency | 14,954 | 35.6% | 11,017 | 38.1% | 3937 | 30.0% | .67 (.64-.70) |

| Discharge from inpatient | 12,364 | 29.4% | 7682 | 26.6% | 4682 | 35.7% | .96 (.92–1.00) |

| Day surgery | 9,301 | 22.1% | 6940 | 24.0% | 2361 | 18.0% | .64 (.61-.68) |

| Payer status | |||||||

| Private/ Commercial† | 14,116 | 33.6% | 9619 | 33.2% | 4497 | 34.2% | REF |

| Public/ Government assistance | 21,027 | 50.1% | 14,304 | 49.5% | 6723 | 51.3% | 1.00 (.97–1.04) |

| Uninsured | 6863 | 16.3% | 4981 | 17.2% | 1882 | 14.4% | .86( .82-.90) |

| Non-opioid drugs co-prescribed | |||||||

| Benzodiazepines | 1,465 | 3.5% | 718 | 2.48% | 747 | 5.70% | -- |

| Muscle Relaxant | 618 | 1.5% | 394 | 1.36% | 224 | 1.71% | -- |

| SSRI/ SNRI | 163 | 0.4% | 74 | 0.26% | 89 | 0.68% | -- |

| Anticonvulsants | 19 | <.1% | 10 | 0.03% | 9 | 0.07% | -- |

| Tricyclic anti-depressants | 18 | <.1% | 7 | 0.02% | 11 | 0.08% | -- |

| Barbiturates | 8 | <.1% | 5 | 0.02% | 3 | 0.02% | -- |

Patients with this characteristic served as the reference group; CI denotes confidence interval; Bold values indicate statistically significant values based on the CI. RR for receiving multiple opioids in patients who also received non-opioid drugs was not calculated, as there is not a hypothesis driven rationale for identifying a reference group.

Demographic characteristics.

See Table 3 for demographic characteristics of patients. Mean age at receipt of first opioid prescription was 13.52 (sd = 6.50), although 38.9% (n=16,327) of patients were young adults (age 18–21 years) at the time of their first prescription. The sample was primarily male (55.0%, n=23,093), of Hispanic/Lantinx ethnicity (50.1%, n=21,044), and most commonly reported races were White (48.3%, n=19,985) and American Indian/Alaskan Native (11.0%, 4,553), although 27.1% (n=11,241) of the sample declined to report their race or it was missing from the medical record. Patient primary language was English (88.9%, n=37,343), followed by Spanish (8.9%, n=3,755). Half of the sample had public or government assisted health insurance (e.g., Medicaid; 50.1%, n=21,027).

Encounter location.

Location of first prescription encounter was most commonly in the emergency department (35.6%, n=14,954) or at discharge from inpatient care (29.4%, n=12,364). Opioid prescriptions were least likely to be prescribed in an outpatient clinic encounter (12.9%, n=5,401).

Total opioid prescriptions.

The majority of youth (68.80%, n=28,911) received only one opioid prescription during the study time frame, while 13,109 (31.20%) received two or more opioid prescriptions (see Table 3). Of the patients who received multiple prescriptions, most received two (56.91%, n=7,460), but 22.2% (n=2,915) received 4 or more opioid prescriptions.

Non-opioid co-prescribed medications.

Regarding other potentially interacting drugs that were co-prescribed with the first opioid, benzodiazepines (e.g. lorazepam) and muscle relaxants (e.g. cyclobenzaprine) were most common. In total, 3.5% of the sample (n= 1465) were co-prescribed a benzodiazepine and 1.5% were co-prescribed a muscle relaxant (n=618). Additionally 0.4% were co-prescribed an SSRI or SNRI (n=163). Individuals were rarely also prescribed anticonvulsants, tricyclic anti-depressants, or barbiturates (< .1%).

Presenting diagnoses.

On average patients had 5.06 (sd = 5.41; range 1–64) presenting diagnoses tied to the encounter where the first opioid prescription was given; thus, baseline diagnoses are not mutually exclusive (see Table 4). Diagnoses were most frequently from the ICD-9 chapters for “Injury and Poisoning” (most common diagnoses in this chapter were ‘fractures’) and “Supplementary Classification of External Causes of Injury and Poisoning’” chapters (most common diagnosis was ‘vehicle related injuries’). More broadly, two thirds of diagnoses (67.8%) were coded as acute conditions, 10.3% represented a chronic pain-related condition (non-cancer), 2.6% were cancer related, 1.5% were for a mental health condition, and 10.3% indicated the presence of another non-pain related medical condition (e.g., metabolic disorders).

Table 4.

ICD-9 chapters for presenting diagnoses at encounter for first opioid prescription (baseline)

| ICD-9 Chapter | N |

|---|---|

| Injury And Poisoning | 34,416 |

| Supplementary Classification Of External Causes Of Injury And Poisoning | 18,142 |

| Supplementary Classification Of Factors Influencing Health Status And Contact With Health Services | 12,152 |

| Symptoms, Signs, And Ill-Defined Conditions | 10,998 |

| Diseases Of The Musculoskeletal System And Connective Tissue | 10,224 |

| Diseases Of The Respiratory System | 8333 |

| Diseases Of The Nervous System And Sense Organs | 8205 |

| Diseases Of The Genitourinary System | 4690 |

| Diseases Of The Digestive System | 4320 |

| Complications Of Pregnancy, Childbirth, And The Puerperium | 4012 |

| Congenital Anomalies | 3662 |

| Diseases Of The Skin And Subcutaneous Tissue | 1966 |

| Mental Disorders | 1899 |

| Neoplasms | 1869 |

| Diseases Of The Circulatory System | 1713 |

| Diseases Of The Blood And Blood-Forming Organs | 1360 |

| Endocrine, Nutritional And Metabolic Diseases, And Immunity Disorders | 1252 |

| Infectious And Parasitic Diseases | 484 |

| Certain Conditions Originating In The Perinatal Period | 88 |

Medication Characteristics and Prescribing Trends over Time

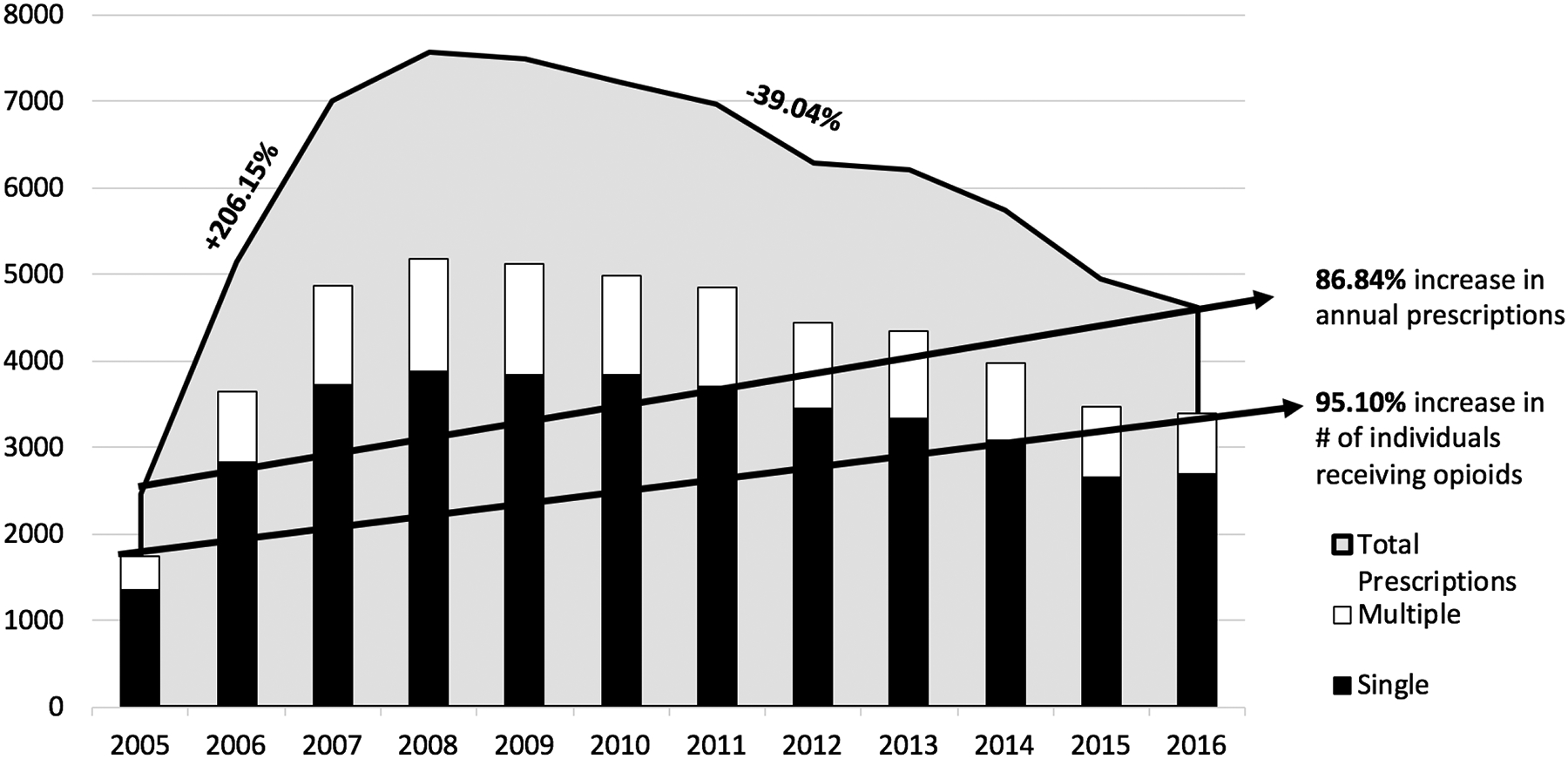

From 2005 to 2016, overall frequency of opioid prescriptions increased by 86.64% (from 2470 to 4620) with the largest increase (206.15%) observed from 2005 to 2008 (2470 to 7562; see Figure 1 and Table 2). Prescribing rates trended downward from 2008 to 2016, decreasing by 39.04%.

Figure 1.

Opioid prescribing trends over time and number of individuals who received single or multiple opioid prescriptions

Number of patients receiving opioids per year increased by 95.10% across the study time frame (from 1736 patients in 2005 to 3387 patients in 2016; Figure 1 or Table 2), with the largest increase (198.16%) occurring from 2005 to 2008, followed by a steady decrease in overall sample size through 2016 (−34.56%).

The raw number of patients receiving multiple prescriptions within a year increased from 391 in 2005 to 689 in 2016, but proportionally only increased from 22.53% of the total sample in 2005 to a peak of 24.96% in 2008, followed by a decrease to 20.34% in 2016 (see Table 2). Thus, the highest number of patients received multiple prescriptions in 2008 (n=1292) and 2009 (n=1277).

Opioid type.

Regarding drug type, Oxycodone was consistently the most commonly prescribed opioid (e.g., OxyContin, Percocet; see Table 5). Overall rates of Oxycodone prescribing increased by 135.32% from 2005 (n=1192) to 2016 (n=2805), peaking in 2010 (n=3389). Tramadol prescriptions increased the most, marked by a 487.5% increase across study time points (from n=16 to 94), including a 600% increase from 2005 to 2013 (from n=16 to 112). Prescription rates for Fentanyl also decreased by 50.0% across the study time points, but only after increasing by 140% from 2005 (n=10) to 2012 (n=24).

Table 5.

Frequency of opioid prescribing over time by type of opioid

| Opioid type | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxycodone | 1192 | 2176 | 2876 | 3417 | 3609 | 3839 | 3453 | 3287 | 3162 | 3065 | 2958 | 2805 | 35839 |

| Hydrocodone | 675 | 1859 | 2425 | 2316 | 2238 | 1958 | 2637 | 2379 | 2393 | 2192 | 1744 | 1530 | 24346 |

| Codeine | 536 | 999 | 1589 | 1672 | 1441 | 1149 | 611 | 425 | 367 | 218 | 77 | 81 | 9165 |

| Morphine | 28 | 60 | 33 | 42 | 102 | 146 | 125 | 64 | 95 | 106 | 43 | 75 | 919 |

| Tramadol | 16 | 17 | 43 | 66 | 53 | 67 | 71 | 75 | 112 | 108 | 96 | 94 | 818 |

| Other | 13 | 16 | 19 | 30 | 26 | 41 | 56 | 41 | 54 | 42 | 26 | 20 | 384 |

| Fentanyl | 10 | 23 | 15 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 21 | 24 | 20 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 176 |

| Yearly Total | 2470 | 5150 | 7000 | 7562 | 7487 | 7215 | 6974 | 6295 | 6203 | 5736 | 4945 | 4610 | 71647 |

Non-opioid co-prescribed medications.

In 2016, almost twice as many individuals receiving their first opioid prescription also had an active prescription for a Benzodiazepine compared to 2005 (n=81 in 2005 and n=159 in 2016; 96.30% increase). Rates of other non-opioid co-prescribed medications remained stable over time.

Receipt of Single versus Multiple Prescriptions

Relative risk of receiving multiple versus single opioid prescriptions significantly increased with age and when morphine or fentanyl was the first opioid prescription type (see Table 3). In particular, adolescents were 1.66 times more likely to receive multiple opioid prescriptions than children age 0–5 years (95% CI= 1.58–1.52). White, English-speaking, not Hispanic/ Lantinx patients were also more likely to receive multiple opioid prescriptions.

Adverse Outcomes

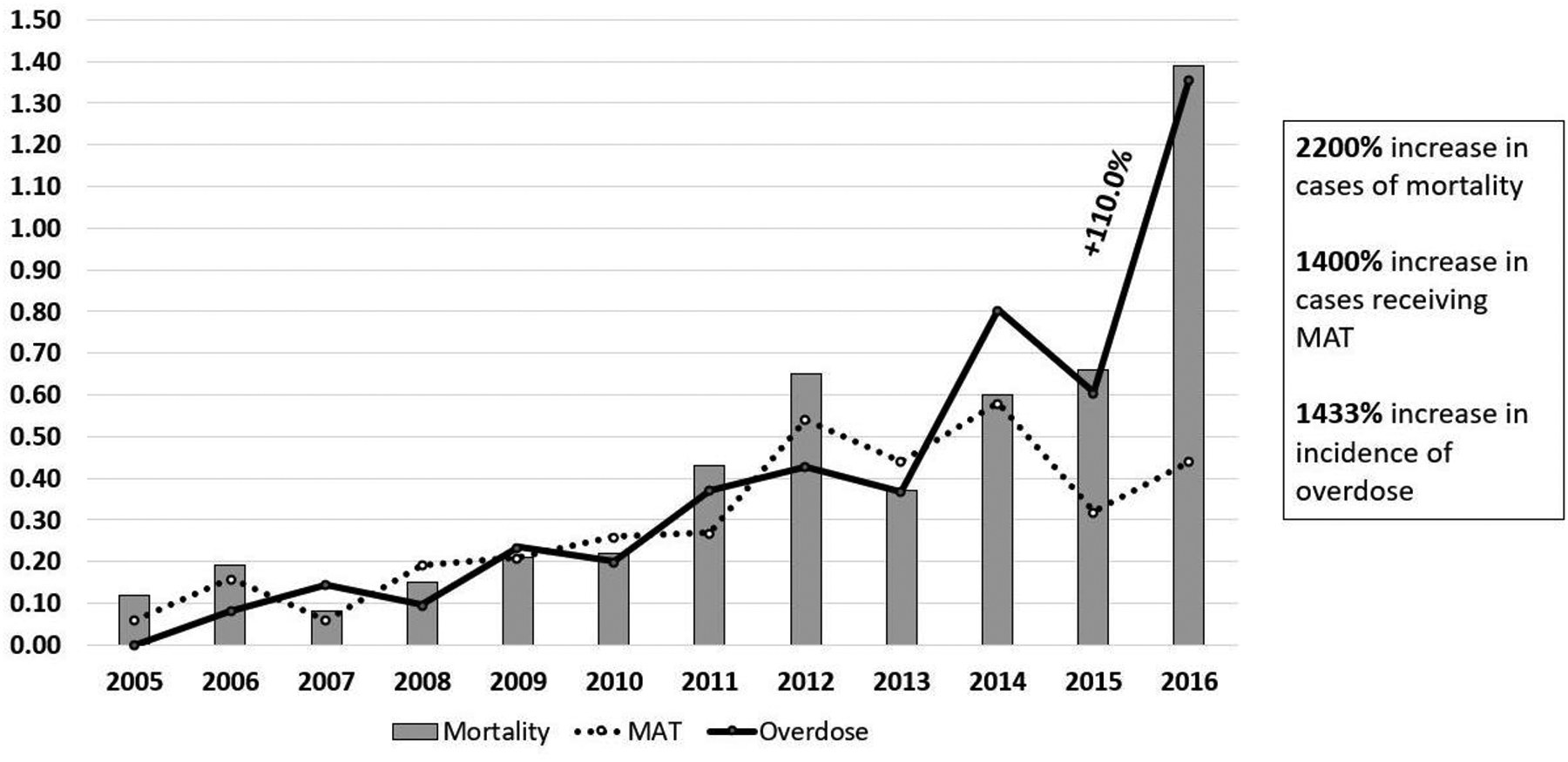

A summary of the frequency of adverse events is in Table 6 and illustrated in Figure 2. Broadly, large increases were observed in the frequency of adverse events from 2005 to 2016: 2200% increase in mortality and 1400% increase in patients receiving medication-assisted, as well as 1433% increase in overdose incidents from 2006 to 2016 (when the first reported overdose incident occurred). Over half of patients with documented adverse outcomes received multiple opioid prescriptions (51.76% of patients who experienced an overdose, 59.73% of patients receiving MAT, and 57.71% of patients who died), which is a higher percentage of patients receiving multiple opioid prescriptions than observed in the total sample (31.20%).

Table 6.

Frequency of markers of morbidity and mortality by year in patients who received single vs. multiple opioid prescriptions

| Year | Total patients who received an opioid prescription | Overdose Incidents | Patients Receiving Medication- Assisted Treatment (MAT) | Mortality Incidents | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single* | Multiple* | Total | % of annual sample* | Single* | Multiple* | Total | % of annual sample* | Single* | Multiple* | Total | % of annual sample* | ||

| 2005 | 1736 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.06% | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.12% |

| 2006 | 3644 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.08% | 2 | 4 | 6 | 0.16% | 2 | 5 | 7 | 0.19% |

| 2007 | 4864 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0.14% | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0.06% | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.08% |

| 2008 | 5176 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0.10% | 3 | 7 | 10 | 0.19% | 5 | 3 | 8 | 0.15% |

| 2009 | 5124 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 0.23% | 3 | 8 | 11 | 0.21% | 5 | 6 | 11 | 0.21% |

| 2010 | 4980 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 0.20% | 6 | 7 | 13 | 0.26% | 3 | 8 | 11 | 0.22% |

| 2011 | 4846 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 0.37% | 5 | 8 | 13 | 0.27% | 8 | 13 | 21 | 0.43% |

| 2012 | 4452 | 7 | 12 | 19 | 0.43% | 13 | 11 | 24 | 0.54% | 10 | 19 | 29 | 0.65% |

| 2013 | 4337 | 6 | 10 | 16 | 0.37% | 10 | 9 | 19 | 0.44% | 9 | 7 | 16 | 0.37% |

| 2014 | 3983 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 0.80% | 12 | 11 | 23 | 0.58% | 9 | 14 | 23 | 0.60% |

| 2015 | 3470 | 11 | 10 | 21 | 0.61% | 4 | 7 | 11 | 0.32% | 6 | 17 | 23 | 0.66% |

| 2016 | 3387 | 26 | 20 | 46 | 1.36% | 2 | 13 | 15 | 0.44% | 24 | 22 | 46 | 1.39% |

| TOTAL | --- | 92 | 97 | 189 | 0.45%** | 60 | 89 | 149 | 0.35%** | 85 | 116 | 201 | 0.48%** |

Denotes if the incident occurred in a patient who received single or multiple opioid prescriptions during the study timeframe.

Percentage of total sample was calculated out of 42,020, number of unique patients in the dataset.

Figure 2.

Percentage of sample who experienced an adverse outcome by year

Overdose.

A total of 189 overdose incidents were reported for 170 individuals (see Tables 6 and 7), as indicated by overdose diagnoses, inpatient admission for treatment of overdose related symptoms, and/or administration of Naloxone. Proportionally, 0.45% of the entire sample experienced an overdose during 2005 to 2016, with the largest annual proportion of patients impacted in 2016 (1.36%) following a 119.05% increase in overdose incidents from 2015 (n=21) to 2016 (n=46). A total of 149 patients (87.60%; see Table 7) experienced 1 overdose, while 21 had two or more documented overdoses (12.49%). The majority of overdose incidents (98.40%; n=186) had documented involvement of an opioid (including both prescription opioids and heroin) in the encounter diagnoses, while 26.50% (n=50) had documentation of prescription opioids specifically. A total of 32 overdose incidents (16.93%) included documentation of active suicidal ideation or suicide attempt via intentional overdose.

Table 7.

Characteristics associated with overdose incidents.

| Year | Unique patients who experienced an overdose by year N=170* |

Total overdose incidents |

Documentation of active suicidal ideation or attempt via intentional overdose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2006 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| 2007 | 7 | 7 | 1 |

| 2008 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| 2009 | 11 | 12 | 4 |

| 2010 | 9 | 10 | 2 |

| 2011 | 17 | 18 | 4 |

| 2012 | 19 | 19 | 1 |

| 2013 | 14 | 16 | 1 |

| 2014 | 29 | 32 | 1 |

| 2015 | 19 | 21 | 2 |

| 2016 | 37 | 46 | 2 |

| TOTAL | * | 189 | 32 (16.93% of incidents) |

| Documented substances at overdose | % | N |

|---|---|---|

| Unspecified opioid | 41.30% | 78 |

| Heroin | 30.70% | 58 |

| Prescription opioids | 22.80% | 43 |

| Prescription opioids & heroin | 3.70% | 7 |

| Other substance | 1.60% | 3 |

| Total Number of Overdoses | % | N |

| 1 | 87.60% | 149 |

| 2 | 9.40%% | 16 |

| 3 | 1.80%% | 3 |

| 4 | 1.20%% | 2 |

Number of unique patients who experienced an overdose =170; since some patients experienced more than one overdose, they are counted in multiple years.

Medication-Assisted Treatment.

The percentage of the entire sample who received a medication for the treatment of opioid dependence (e.g., buprenorphine, naltrexone, methadone, and buprenorphine-naloxone [Suboxone]) within 1 year of receipt of an opioid prescription increased from .06% in 2006 (n=1 out of 1736) to .44% in 2016 (n=15 out of 3387), although was highest in 2014 (.58%; n=23 out of 3983).

Mortality.

Data was extracted on all incidents of mortality for subjects in the study sample, not deaths only related to opioid use. Documented incidence of mortality in individuals prescribed an opioid increased by 2200% from 2 individuals in 2005 to 46 in 2016 (from .12% of the sample to 1.39%), impacting a total of 201 patients. Similar to overdose rates, mortality incidents increased most significantly from 2015 (n=23) to 2016 (n=46; an increase of 100%). Cause of mortality was unknown for most patients. On average, deaths occurred 3.40 years (sd= 3.24; range 0–13 years) after receipt of the first opioid prescription.

Differences in Outcomes Based on Medication and Individual Characteristics

Table 8 includes a summary of medication-related and demographic characteristics of patients with documented markers of morbidity and mortality following receipt of an opioid prescription as well as relative risk of experiencing adverse outcomes based on these characteristics. Overall, increased risk for adverse outcomes differed significantly based on type of first opioid prescription, older age, minority status (specifically for mortality), encounter type, payer status, and receipt of multiple prescriptions.

Table 8.

Medication and demographic characteristics of patients with markers of morbidity and mortality after an opioid prescription

| Overdose N= 170 |

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) N= 149 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Risk (95% CI) | Relative Risk (95% CI) | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| 1.83 (.84–4.00) | 0.67 (.23–1.94) | ||

| 1.04 (.46–2.34) | 0.73 (.27–1.96) | ||

| 1.02 (.45–2.31) | 0.59 (.21–1.64) | ||

| 1.16 (.52–2.60) | 1.42 (.57–3.51) | ||

| 1.15 (.51–2.69) | 1.33 (.53–3.32) | ||

| 0.66 (.27–1.61) | 0.66 (.24–1.85) | ||

| 0.61 (.24–1.53) | 1.94 (.79–4.74) | ||

| 0.49 (.19–1.32) | 1.24 (.48–3.18) | ||

| 0.69 (.27–1.74) | 1.10 (.41–2.92) | ||

| 0.16 (.03-.73) | 0.94 (.33–2.63) | ||

| 0.32 (.10–1.07) | 0.64 (.21–2.00) | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| 2.37(1.75–3.20) | 3.27 (2.36–4.54) | ||

| 1.70 (1.15–2.52) | 2.20 (1.44–3.34) | ||

| 2.19 (1.30–3.69) | 2.11 (1.14–3.93) | ||

| 4.23 (2.86–6.28) | 7.11 (4.81–10.50) | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| .55 (.39-.78) | .33 (.31-.51) | ||

| .31 (.17-.57) | .33 (.18-.62) | ||

| 2.14 (.68–6.70) | 3.32 (1.23–8.96) | ||

| -- | 22.40 (13.5–37.15) | ||

| -- | -- | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| 8.18 (4.32–15.49) | 3.50 (2.16–5.66) | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| 2.55 (.66–9.87) | .62 (.25–1.62) | ||

| 8.42 (2.60–27.25) | 2.11 (1.10–4.01) | ||

| 18.36 (5.84–57.71) | 3.52 (1.88–6.26) | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| 1.14 (.84–1.55) | .58 (.42-.15) | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| .98 (.70–1.37) | 1.23 (.85–1.78) | ||

| -- | -- | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| .83 (.51–1.35) | .82 (.49–1.37) | ||

| 2.30 (1.34–3.94) | 2.04 (1.12–3.71) | ||

| -- | -- | ||

| 15.73 (10.75–23.0) | 13.7 (9.00–21.04) | ||

| -- | -- | ||

| -- | -- | ||

| -- | -- | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| .18 (.06-.56) | -- | ||

| -- | -- | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| 1.33 (.87–2.05) | .39 (.25-.59) | ||

| .52 (.31-.88) | .62 (.42-.93) | ||

| .29 (.15-.56) | .07 (.03-.18) | ||

| REF | REF | ||

| 1.23 (.83–1.80) | 2.11 (1.38–3.23) | ||

| 2.93 (1.96–4.39) | 2.42 (1.47–4.01) | ||

Patients with this characteristic served as the reference group; % of Total Sample is also known as “Absolute Risk”; CI denotes confidence interval; Bold values indicate statistically significant values based on the CI; AYA= Adolescents & Young Adults; AI/AN= American Indian/ Alaska Native; AA=African American

Medication characteristics.

Year of first opioid.

Patients who died or received MAT most commonly received their first opioid prescription in 2012 or earlier. Patients who experienced an overdose most commonly received their first opioid prescription from 2006– 2009, consistent with overall prescribing trends within the dataset.

Type of first opioid prescription.

Patients who experienced an overdose or received MAT were most commonly prescribed Oxycodone. Receipt of Morphine was associated with a 22.40-fold (95 CI=13.5–37.15) increased risk of receiving MAT and a 64.39-fold increased risk of death (95% CI= 44.91–92.34) than Oxycodone. Similarly, the risk of receiving MAT or of mortality after receipt of a Tramadol prescription was 3.32 times (95% CI= 1.23–8.96) and 32.63 times (95% CI= 8.75–121.69) greater than Oxycodone.

Encounter type.

In comparison to outpatient clinic encounters, relative risk for adverse outcomes was significantly reduced when receiving the first opioid prescription during an emergency, inpatient discharge, or day surgery encounter. Further, in relation to the total sample, 1.20% of the sample (n=65) who received an opioid prescription during an outpatient clinic encounter died.

Frequency of opioid prescription.

A larger proportion of patients receiving multiple opioid prescriptions experienced adverse outcomes as compared to patients who received only one opioid prescription. Most notably, of all patients who received four or more opioid prescriptions, 1.20% experienced an overdose (n=35), 1.48% received MAT (n=43), and 2.16% died (n=63). For comparison, 0.21–0.29% of all patients who received a single opioid prescription experienced an adverse outcome. Relative risk of adverse outcomes for individuals receiving multiple opioid prescriptions versus single prescriptions steadily increased as number of prescriptions increased. In particular, in patients who received 4 or more opioid prescriptions, the risk of overdose was 4.23 times greater (95% CI= 2.86–6.28), the risk of receiving MAT was 7.11 times greater (95% CI= 4.81–10.50), and the risk of mortality was 7.35 times greater (95% CI=5.32–10.16).

Individual characteristics.

Age at first opioid prescription.

The majority of patients who experienced an overdose (94.12%, n=160) or received MAT (87.24%, n=130) received their first opioid prescription during adolescence (age 12–17 years) or as a young adult (age 18–21 years). Subsequently, adolescents and young adults were at increased risk of adverse events relative to youth age 11 and under, particularly overdose (RR=8.18, 95% CI= 4.32–15.49) and MAT (RR=3.50, 95% CI= 2.16–5.66). Age at first opioid prescription in patients who died was more varied: 32.34% (n=65) of deceased patients received their first opioid prescription during adolescence, while 28.86% were age 0–5 years are receipt of first opioid (n=58).

Sex.

Males were 1.35 times more likely to die (95% CI- 1.01–1.79) in comparison to females. Proportionally, more females than males received MAT (58.39%, n=87).

Ethnicity, Race, and Primary Language.

Proportionally, within the entire sample, more racial minority patients died than white patients. Specifically, 4.34% (n=18) of all Asian patients, 2.17% of all Black/ African American patients, and 1.45% of American Indian/ Alaska Native patients died in comparison to 0.43% of all White patients; Additionally, relative risk of death was significantly greater in minority patients in comparison to White patients (3.41–10.20x greater). Equal proportions of the entire sample of Hispanic/Lantinx and Not Hispanic/Lantinx identifying patients died (.45% and .46%, respectively), although a greater frequency of deaths occurred in Hispanic/Lantinx patients (n=96, 46.27%, vs. n=53, 26.37%, of Non-Hispanic/Lantinx patients).

Overdose occurred most often in Hispanic/Lantinx (n=95, 55.89%, 0.45% of the total sample) and White patients (n=101, 59.42% of overdoses; 0.51% of the total sample. Similarly, Hispanic/Lantinx patients (n=90, 60.40%, 0.43% of the total sample) and White patients (n=91, 61.07%, 0.46% of the total sample) were more likely to receive MAT. Proportionally, within the entire sample, a marked 6.27% (n=26) of Asian patients received MAT and these patients were at 13.27 times higher risk (95% CI= 9.00–21.04) of receiving MAT compared to White patients. Primary language was English for nearly all patients experiencing adverse outcomes (87.56%- 96.79%), consistent with the full sample.

Payer Status.

Public/government assistance (e.g., Medicaid) was the most common type of insurance for patients experiencing all three outcomes (42.78%−60.70%). Patients who were uninsured were 2.93 times more likely to experience an overdose (95% CI= 1.96–4.39) and 2.42 more likely to receive MAT (95% CI= 1.47–4.01) when compared to privately insured patients.

Discussion

This study used medical records to evaluate opioid prescription rates in youth in NM. Further, individual factors and outcomes associated with receipt of single or repeat prescriptions and adverse outcomes were characterized to increase understanding of the prevalence and impact of opioid prescriptions. Unique aspects of this study are the young age range and racial/ethnic diversity of the sample, geographic location (rural, high-risk state for opioid use), utilization of hospital medical records data (rather than insurance claims data or patient self-report), consideration of individual factors associated with receipt of multiple opioid prescriptions, and preliminary evaluation of longitudinal outcomes following receipt of an opioid prescription.

Overall, substantial increases in prescription of opioids as well as rates of morbidity and mortality were observed. Despite downward trends in prescribing rates from 2008 to 2016, increases in morbidity and mortality persisted. Patients who were older, White, not Hispanic/ Lantinx, and English-speaking were more likely to receive multiple opioid prescriptions, which is consistent with previous literature related to individual factors associated with receipt of any opioid [19,37,44,56], but not necessarily multiple opioids, as we are not aware of any preexisting data in that domain. Increased risk of adverse outcomes was observed in patients receiving multiple opioid prescriptions, as well as patients who were older, of a minority racial background, publicly insured or uninsured, received their first prescription in an outpatient clinic setting, and who received Tramadol, Fentanyl, or Morphine as a first opioid prescription. In particular, there was an association between age at time of prescription and increased risk of adverse outcomes - a finding with direct clinical implications for prescribing practices.

Prescription of opioids to youth in NM appear to be occurring with greater frequency in comparison to national prescribing trends (e.g., [19]), which we were unable to attribute to hospital level growth. Interestingly, national data indicate that prescribing rates to youth in the United States remained stable and low, but with significant increases in youth receiving five or more opioid prescriptions. Prescribing trends to youth in NM appear more similar to adult prescribing trends in the US [26,46,53], particularly when examined in relation to the high rates of morbidity and mortality. Also consistent with national findings in adults, decreases in opioid prescribing within this sample did not equate to decreases in morbidity and mortality [5,22,42,53].

Variance in pediatric opioid prescribing rates and adverse outcomes between states underscores the need for national consensus on pediatric-specific opioid prescribing guidelines [11,45,48], as currently available guidelines are intended for adults [1,7,8,13]. Additionally, most analgesics do not have FDA pediatric labeling. While the FDA has approved OxyContin prescription in pediatric patients, this decision was made without releasing supporting data [45]. An immediate need is to generate empirically supported guidance on opioid usage in youth.

Although not explicitly captured in this dataset, there are several identified “risk factors” [18] for opioid misuse which are common among youth in NM and may increase vulnerability to adverse outcomes, potentially illuminating differences between state and national prescribing rates. Specifically, NM is one of five state states with significantly higher rates of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) than national levels, where up to one in seven children experience three or more ACEs [43] a risk factor for opioid use in adulthood [18]). In NM there are also high rates of substance use in utero as well as adolescent substance use [16]. Further, over a third of third of youth in NM grow up in poverty [16] and geographically NM is primarily rural. Previous work has identified adolescents living in rural areas as being at 35% greater odds of engaging in prescription opioid misuse [33] and high opioid prescribing rates have been recorded geographically in the southern United States [41], but not NM in particular. If using insurance status as a proxy for socioeconomic status, results from the current study indicate that patients who were uninsured were more likely to experience an overdose, which is consistent with adult literature [10]. Additionally, unmanaged pain has been repeatedly identified as a primary motive for non-prescribed opioid use in adolescents [31]. At this time, NM does not have a specialized interdisciplinary pediatric pain rehabilitation program [2], and access to non-pharmacological evidence-based pain management resources is limited.

While cause of death for patients in the sample is unknown, the large increase in mortality within the sample is worrisome. Death rates in children and adolescents within the state have not increased, although, drug overdose deaths in NM have risen since 2001 [16]. Consistent with the present sample, American Indian youth in NM die at more than twice the rate of other racial groups. A notable subset of early childhood aged children died (age 0–5 years; n=58, .78% of the total sample of that age group); it is unclear if these deaths were related to accidental injury/ overdose or perhaps greater disease severity (e.g., cancer). The finding that youth prescribed Fentanyl were more likely to die should be interpreted with caution and within this clinical context, rather than in relation to rising synthetic/ illicit Fentanyl-related death rates in the US, as prescription Fentanyl use with children is fairly rare, except during palliative care.

Increases in youth receiving medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for an opioid use disorder (OUD) is a finding that comes with mixed implications. This finding may be reflective of an increase in incidence of OUD or an increase in patients accessing treatment for an OUD; the first case would be a disappointing but not unexpected finding, while the second would be a testament to progress in identifying and treating patients with OUD. Increases in adolescents and young adults seeking MAT for an opioid use disorder further highlights previous findings [17] regarding the need to increase access to developmentally-appropriate behavioral treatments in conjunction with MAT.

Finally, results in the current study underscore previously documented relations between prescription opioid use and suicidal ideation [12] and emphasizes the importance of monitoring patient mental health, as well as providing education to families on safe storage and disposal of leftover opioids. Clinically, it is recommended that pediatric providers screen for psychosocial factors associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes (e.g., using the CRAFFT [23,32]), implement risk mitigation strategies, and consider utilization of non-pharmacological pain managements strategies for all patients, but in particular in documented higher-risk patient populations (e.g., older adolescents) and treatment settings (outpatient clinic) as well as before giving a second opioid prescription to any child.

Limitations

Medical records present a unique opportunity to understand the evolution of opioid prescribing. However, medical records are not designed to accomplish research aims, and therefore are subject to limitations. In this study, there was no way to confirm if prescriptions were filled, if patients sought additional prescriptions from providers outside of this hospital system, if the first opioid prescription received during the study timeframe was the patient’s first exposure to prescribed opioids, or a definitive estimation of patient medical complexity. Adverse outcomes were analyzed by only those treated within the UNMH system and cannot be causally linked to receipt of an opioid prescription. Additionally, due to de-identification procedures it was not possible to calculate length of time between prescriptions or patient zip code (geo coding). Finally, less than 20% of prescriptions had adequate data (e.g., dose and frequency) to calculate morphine equivalent dose. It is also a limitation that a subset of patients declined to report or had missing values for race (27.1%) and/or ethnicity (22.5%).

Conclusions and Significance

As life expectancy in the US has declined for two years in a row, attributable largely to the increase in opioid overdose-related mortality among young adults and adults [25], the importance of quantifying opioid prescription rates to youth, a key access point for nonmedical use, and associated adverse outcomes cannot be overstated. This is the first epidemiological study using hospital-level data to examine opioid prescribing rates and longitudinal outcomes specifically to children and adolescents in a high-risk state. Much of the available research on opioid prescribing rates to youth has been primarily derived from insurance claim databases [19,39], limiting the clinical utility and generalizability of findings.

Specifically, this study contributes to the growing literature identifying factors associated with receipt of opioid prescriptions in youth and risk factors predictive of less favorable outcomes, including overdose and death, and can be used to inform prescribing practices in the state. A new finding from this dataset is that, consistent with adult literature, receipt of more than one opioid prescription was associated with greater risk for adverse consequences, highlighting potential additive risks of adverse outcomes when pediatric patients receive multiple opioid prescriptions. It will be informative to see whether this finding is replicated in other similar samples. Finally, the large difference in trends of opioid prescribing rates to youth in NM versus nationally suggests that national statistics may not be accurately representative of all states. In order to effectively and appropriately distribute intervention and treatment resources, trends may need to be evaluated locally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements & Funding

This study was funded by the Center for Regional Studies at the University of New Mexico (PI: Pielech). Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (F32 DA049440–01, PI: Pielech) and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (R34 AT08398, PI: Vowles). This project was also supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translation Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (ULITR001449) at the University of New Mexico Clinical and Translational Sciences Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report

References

- [1].American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society, American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public Policy Statement on the Rights and Responsibilities of Healthcare Professionals in the Use of Opioids for the Treatment of Pain. 2004;2 Available: http://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/1opioid-rights-consensus-format-4-04.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed 31 Aug 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [2].American Pain Society. Pediatric Chronic Pain Programs by State. 2015. p. Available: http://americanpainsociety.org/uploads/get-involved/PediatricPainClinicList_Update_2.10.15.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2016.

- [3].Binswanger IA, Glanz JM. Pharmaceutical opioids in the home and youth: implications for adult medical practice. Subst Abus 2015;36:141–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Center for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2014 on CDC WONDER Online Database. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause of Death 1999–2013 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released 2015. 2015. p. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cerdá M, Santaella J, Marshall BDL, Kim JH, Martins SS. Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use in Childhood and Early Adolescence Predicts Transitions to Heroin Use in Young Adulthood: A National Study. J Pediatr 2015;167:605–12.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Adler JA, Ballantyne JC, Davies P, Donovan MI, Fishbain DA, Foley KM, Fudin J, Gilson AM, Kelter A, Mauskop A, O’Connor PG, Passik SD, Pasternak GW, Portenoy RK, Rich BA, Roberts RG, Todd KH, Miaskowski C. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain 2009;10:113–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Costello M Prescription Opioid Analgesics: Promoting Patient Safety with Better Patient Education. Am J Nurs 2015;115:50–56. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000473315.02325.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Curtain SC, Tejada-Vera B, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths Among Adolescents Aged 15–19 in the United States: 1999–2015. Atlanta, GA, 2017. p. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db282.htm. Accessed 25 Feb 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, Nahin R, Mackey S, DeBar L, Kerns R, Von Korff M, Porter L, Helmick C. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1001–1006. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dash GF, Wilson AC, Morasco BJ, Feldstein Ewing SW. A Model of the Intersection of Pain and Opioid Misuse in Children and Adolescents. Clin Psychol Sci 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Divin AL, Zullig KJ. The Association between Non-Medical Prescription Drug Use and Suicidal Behavior among United States Adolescents. AIMS public Heal 2014;1:226–240. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2014.4.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. 2016. p. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Caiola E, Joynt M, Halterman JS. Prescribing of controlled medications to adolescents and young adults in the United States. Pediatrics 2010;126:1108–16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, Camenga DR. National Trends in Hospitalizations for Opioid Poisonings Among Children and Adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr 2016;06520:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gallagher L, Landen MG, Baca J, Bartok A, Baum S, Baumbach J, Chacon S, Coronado E, Faulkner K, Galbraith R, Gallegos A, Gans A, Geter K, Green D, Haggard L, Hubbard G, Hughes K, Kelley G, Kirlin C, Krapfl H, Lam S, Mahdi I, Mcphee J, Moss C, Murphy T, Padilla J, Ritchie L, Ropri A, Rosenblatt T, Sievers M, Smelser C, Thomas J, Toth B, Waters J, Whiteside C, Wilkerson D, Walker A. The State of Health in New Mexico New Mexico Department of Health Acknowledgments New Mexico Department of Health Epidemiology and Response Division Chapter Authors for the State of Health in New Mexico 2018 Report Graphic Design NM-IBIS Indicator Report Authors NMDOH Data Stewards. 2018. p. Available: https://ibis.health.state.nm.us/query/DataStewards.html. Accessed 2 Mar 2019.

- [17].Greenfield BL, Owens MD, Ley D. Opioid use in Albuquerque , New Mexico : a needs assessment of recent changes and treatment availability. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2014;9:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Groenewald CB, Law EF, Fisher E, Beals-Erickson SE, Palermo TM. Associations Between Adolescent Chronic Pain and Prescription Opioid Misuse in Adulthood. J Pain 2019;20:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Groenewald CB, Rabbitts JA, Gebert T, Palermo TM. Trends in opioid prescriptions among children and adolescents in the United States. Pain 2015;157:1021–1027. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Højsted J, Nielsen PR, Guldstrand SK, Frich L, Sjøgren P. Classification and identification of opioid addiction in chronic pain patients. Eur J Pain 2010;14:1014–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Corp IBM. Released. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. 2015 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical Overdose Deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA 2013;309:657. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, Harris SK, Chang G. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:607–14. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12038895. Accessed 8 Dec 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kobus AM, Smith DH, Morasco BJ, Johnson ES, Yang X, Petrik AF, Deyo RA. Correlates of higher-dose opioid medication use for low back pain in primary care. J Pain 2012;13:1131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kochanek K, Murphy S, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2016. Hyattsville, MD, 2017. p. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten-year perspective. Pain Physician 2010;13:401–35. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20859312. Accessed 18 May 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mars SG, Bourgois P, Karandinos G, Montero F, Ciccarone D. “Every ‘never’ I ever said came true”: transitions from opioid pills to heroin injecting. Int J Drug Policy 2014;25:257–66. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mazer-Amirshahi M, Mullins PM, Rasooly IR, van den Anker J, Pines JM. Trends in prescription opioid use in pediatric emergency department patients. Pediatr Emerg Care 2014;30:230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].McCabe SE, Veliz P, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent context of exposure to prescription opioids and substance use disorder symptoms at age 35. Pain 2016:1. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Leftover prescription opioids and nonmedical use among high school seniors: A multi-cohort national study. J Adolesc Heal 2013;52:480–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Motives for medical misuse of prescription opioids among adolescents. J Pain 2013;14:1208–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].McCabe SE, West BT, Teter CJ, Cranford J a, Ross-Durow PL, Boyd CJ. Adolescent nonmedical users of prescription opioids: brief screening and substance use disorders. Addict Behav 2012;37:651–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Monnat SM, Rigg KK. Examining Rural/Urban Differences in Prescription Opioid Misuse Among US Adolescents. J Rural Heal 2015;32:n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].New Mexico Department of Health. Health Indicator Report of Drug Overdose Deaths. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Osborne V, Serdarevic M, Crooke H, Striley C, Cottler LB. Non-medical opioid use in youth: Gender differences in risk factors and prevalence. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Palamar JJ, Shearston JA, Dawson EW, Mateu-Gelabert P, Ompad DC. Nonmedical opioid use and heroin use in a nationally representative sample of us high school seniors. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;158:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA 2008;299:70–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].R Core Team. R Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Found Stat Comput Vienna, Austria: URL http//wwwR-project.org/ 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Richardson LP, Fan MY, McCarty C a, Katon W, Edlund M, DeVries A, Martin BC, Sullivan M. Trends in the prescription of opioids for adolescents with non-cancer pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011;33:423–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Richardson LP, Russo JE, Katon W, McCarty C a, DeVries A, Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Sullivan M. Mental health disorders and long-term opioid use among adolescents and young adults with chronic pain. J Adolesc Heal 2012;50:553–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rolheiser LA, Cordes J, Subramanian SV. Opioid Prescribing Rates by Congressional Districts, United States, 2016. Am J Public Health 2018;108:1214–1219. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths - United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;64:1378–82. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sacks V&MD. The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences, nationally, by state, and by race or ethnicity - Child Trends. 2018. Available: https://www.childtrends.org/publications/prevalence-adverse-childhood-experiences-nationally-state-race-ethnicity. Accessed 25 Nov 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sadhasivam S, Chidambaran V, Ngamprasertwong P, Esslinger HR, Prows C, Zhang X, Martin LJ, McAuliffe J. Race and unequal burden of perioperative pain and opioid related adverse effects in children. Pediatrics 2012;129:832–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Schechter NL, Walco GA. The Potential Impact on Children of the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain Above All , Do No Harm. JAMA Pediatr 2016:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Shaheed CA, Maher CG, Williams KA, Day R, Mclachlan AJ. Efficacy, Tolerability, and Dose-Dependent Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2016:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sheridan DC, Laurie A, Hendrickson RG, Fu R, Kea B, Horowitz BZ. ASSOCIATION OF OVERALL OPIOID PRESCRIPTIONS ON ADOLESCENT OPIOID ABUSE. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Slater ME, De Lima J, Campbell K, Lane L, Collins J. Opioids for the management of severe chronic nonmalignant pain in children: A retrospective 1-year practice survey in a children’s hospital. Pain Med 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD, 2017. p. Available: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Substance Abuse Epidemiology Section New Mexico Department of Health. New Mexico Substance Abuse Epidemiology Profile. 2016. p. [Google Scholar]

- [51].The Regents of the University of Michigan. Monitoring the Future (MTF). Univ Michigan; 2016. Available: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Voepel-Lewis T, Wagner D, Tait AR. Leftover Prescription Opioids After Minor Procedures: An Unwitting Source for Accidental Overdose in Children. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:497–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Siyahhan P, Frohe T, Ney JP, van der Goes DN. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiciton in chronic pain : A systematic review and data synthesis. Pain 2015;156:569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Walco GA, Gove N, Phillips J, Weisman SJ. Opioid Analgesics Administered for Pain in the Inpatient Pediatric Setting. J Pain 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Welsh JW, Knight JR, Hou SS-Y, Malowney M, Schram P, Sherritt L, Boyd JW. Association Between Substance Use Diagnoses and Psychiatric Disorders in an Adolescent and Young Adult Clinic-Based Population. J Adolesc Heal 2017;60:648–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Wu L-T, Woody GE, Yang C, Pan J-J, Blazer DG. Racial/ethnic variations in substance-related disorders among adolescents in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:1176–85. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.