Abstract

Development is a cumulative, lifelong process, but we know strikingly little about development in midlife. As a consequence, many misconceptions exist about the nature of midlife and the developmental milestones and challenges faced by middle-aged adults. We first review dominant views and empirical research that has debunked false narratives. Next, we discuss major opportunities and challenges of midlife. This includes the unique constellation of roles and life transitions that are distinct from earlier and later life phases as well as shifting trends in mental and physical health and in family composition. We additionally highlight the importance of (historical shifts in) intergenerational dynamics of middle-aged adults with their aging parents, adult children, and grandchildren; financial vulnerabilities that emerge and often accrue from economic failures and labor market volatility; the shrinking social and healthcare safety net; and the rising costs of raising children. In doing so, we discuss issues of diversity and note similarities and differences in midlife experiences across race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. We consider midlife as a pivotal period that includes a focus on balancing gains and losses, linking earlier and later life periods, and bridging generations. Finally, we propose possibilities for promoting reversibility and resilience with interventions and policy changes. The suggested agenda for future research promises to re-conceptualize midlife as a key period of life, with a concerted effort to focus on the diversity of midlife experiences in order to meet the unprecedented challenges and opportunities in the 2020s and beyond.

Keywords: Lifespan Development, Policy Implications, Current and Dominant narratives, Financial Vulnerabilities, Promoting Reversibility and Resilience

Development is a cumulative, lifelong process (Baltes, 1987). Although midlife comprises a large portion of adulthood and important life transitions, we are only at the very beginning of understanding this life phase and how it may differ from other periods of adulthood (Lachman, 2004). The narrative surrounding midlife needs to move beyond the misconceptions tied to the midlife crisis to consider midlife as a vibrant period with unprecedented opportunities and challenges. To make the case, the current article pursues three objectives. First, we provide a brief overview of dominant narratives about midlife and the empirical evidence that supports or refutes the claims. Second, we identify opportunities and challenges that distinguish midlife from other life stages, with an emphasis on diversity across race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Third, we discuss interventions and policies to address the unique developmental questions related to the opportunities and challenges of midlife. Pursuing these three objectives promises to re-conceptualize midlife as a key life stage, with distinct and unprecedented opportunities and challenges to be met in the 2020s and beyond.

Dominant Narratives and Perspectives about Midlife

Early Theories of Midlife

The most well-known theories of midlife are those of Carl Jung and Erik Erikson (Lachman & James, 1997). Jung referred to midlife as the afternoon of life and thought of it as a period distinct from early and later adulthood. Erikson’s (1993) stage theory of development considers the psychosocial conflict in midlife to revolve around generativity vs. stagnation and self-absorption. Middle-aged adults devote time and effort into nurturing and promoting younger generations and creating goods that will last past their lifetime. Being generative can occur in a wide range of pursuits: parenthood and grandparenthood, work and professional activities, volunteering, and religious/political organization participation (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992).

Although midlife has received far less research attention than other age periods, the situation is slowly changing. The Midlife in the United States Study (MIDUS) has been instrumental in bringing to light the importance of explicitly studying individuals in midlife across psychosocial, cognitive, and health developments; dynamics of daily life; and physiological and neurological correlates (Brim et al., 2004; Ryff & Krueger, 2019). By now, midlife-relevant questions can fortunately be examined using an increasing number of longitudinal panel surveys that include adults in midlife (e.g., HRS, SHARE, ELSA, SOEP, HILDA, and MIDJA).

Researchers and the public have generally considered midlife to encompass the ages of 40 to 60, plus or minus 10 years, making it a relative approximation. When polled about when midlife begins and ends, people, on average, believed it begins at age 44 (SD=6.15) and ends at age 59 (SD=7.46; Lachman et al., 2015). Such age boundaries though are secondary. More important for defining midlife than chronological age are the unique role constellations that people take on combined with the timing of life events and experiences (Lachman, 2004).

U-shaped Curve in Well-Being across Adulthood

Much work has focused on how middle-aged adults compare to other ages in well-being. There are many large studies that show a low point in life satisfaction during the middle years (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2008; Stone et al., 2010). Although these results have been replicated in many samples across nations, most of the study designs are cross-sectional, and findings differ from longitudinal studies. Longitudinal research from multiple panel surveys has shown instead that well-being is high and stable in midlife and hedonic aspects and emotional experience exhibit upward trajectories (Baird et al., 2010; Carstensen et al., 1999; Galambos et al., 2015). The noted cross-sectional age differences in well-being are typically rather small; nevertheless, the U-shaped curve findings are often interpreted as evidence for a widespread midlife crisis.

Midlife Crisis

One dominant narrative surrounding midlife involves the “midlife crisis”. Elliott Jaques (1965) first coined this term through observing in his midlife client’s abrupt changes in lifestyle and productivity as well as coming face-to-face with one’s own limitations and ever-increasing salience of mortality. The stereotypical images are buying a red sports car, marrying someone significantly younger, or elective surgery to look younger. Occurrence of the midlife crisis has turned out to be myth; research shows 10–20% of people actually experience it (Lachman, 2004; Wethington, 2000). Although some consider it humorous and the focus of jokes, movies, and TV shows, negative repercussions from promoting the crisis as normative include ignoring mental or physical health problems when attributing the symptoms to a midlife crisis (Lachman, 2015).

Another example of a supposed crisis in midlife is the empty nest phenomenon. The initial conception was that after decades of caring for children, women – especially those whose primary role was mother – would be depressed after their children left home. It was also assumed that spouses would have to re-negotiate their relationship. The empirical evidence sketches a differentiated pattern, ranging from women finding new roles over the noted identity and marital conflicts for some to a positive time for others because spouses take on the opportunity to reconnect and rekindle interests (Mitchell, 2006). Challenges for adjustment may arise when cultural, social, or personal norms about adult roles and educational paths are not congruent between parents and their adult children (Mitchell, 2006; Settersten & Hagestad, 1996).

Opportunities and Challenges in Midlife

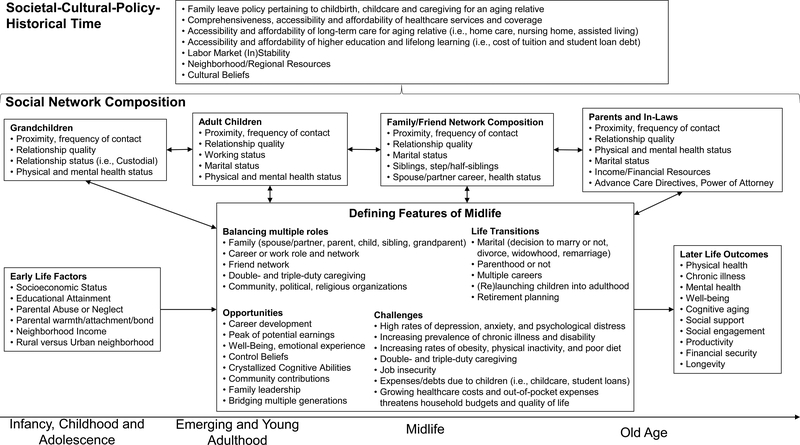

Figure 1 illustrates our guiding conceptual framework of how midlife constitutes a pivotal period in the lifespan. Figure 1‘s overarching goal is to demonstrate how the study of midlife involves a complex interplay of examining individual level trends across pertinent domains (central box labeled ‘Defining Features of Midlife’), middle-aged adults’ central role in bridging generations (represented by the double-headed arrows across aspects of one’s social network composition who are at different stages of the lifespan) and the important role of macro-level forces, such as culture and policy in impacting this interplay. As we elaborate in further detail below, the defining features of midlife are represented in the central box and constitute the unique constellations of balancing multiple roles, life transitions, opportunities and challenges. The significance of midlife is conveyed in middle-aged adults’ connectedness with network members within and across generations (grandchildren, adult children, family/friend network and parents/in-laws) and that development in midlife is a temporal process that unfolds in the societal-cultural-policy-historical time context. The sequence of the connectedness, its stability and change, and the dynamic and plastic nature of the life structure — that is, the underlying pattern or design of a person’s life at a given time (see Levinson, 1986) — across pertinent domains will differ based on race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and the timing of transitions/events (discussed further below).

Figure 1.

A Lifespan Perspective on Midlife. Guiding conceptual framework that portrays midlife as a pivotal period in the life course. Midlife is best defined by balancing multiple roles, life transitions, opportunities and challenges. These defining features of midlife transpire across the typically defined age periods of adulthood (i.e., young adulthood, midlife, and into old age). Early life factors, such as SES, parental relationships, and neighborhood factors shape the nature of midlife, which in turn affects outcomes such as health and well-being in later life. Current cohorts of middle-aged adults are confronted with increases in the intensity, magnitude, or sheer load of concurrently balancing multiple roles and challenges, while typically being responsible for those younger and older in the family and contending with increasing prevalence of chronic illness, disability, obesity and mental health issues. The challenges of midlife are offset by opportunities, such as career development, peak of earnings, gains in well-being, control beliefs, and bridging multiple generations. Social network composition details the significance of middle-aged adults’ connectedness with multiple generations, including their parents/in-laws, spouse/partner, adult children, and grandchildren. The form, function, and structure of social network composition across the multiple generations shown in Figure 1 is dependent on a variety of factors, such as the proximity, frequency of contact, and relationship quality with network members, their cognitive, mental, and physical health status, one’s own and family members’ marital status and number of children. The Societal-Cultural-Policy-Historical Time context that middle-aged adults and their social network composition reside carry great significance. Government policies and cultural beliefs have implications for development in midlife and connectedness with social network members. As discussed in the text, important considerations for this component include family leave policy, healthcare services and coverage, and higher education. The timetable of midlife can be shifted for numerous reasons, including age of parents, timing and decision of having kids, and if/when adult children have children. Targets for intervention can span multiple levels, including physical activity, social support and engagement, workplace and policy. Lastly, the life structure or the underlying pattern or design of a person’s life at a given time will differ across race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation and SES.

As the population in midlife increases and circumstances change, there is a need to focus attention on key opportunities and challenges middle-aged adults are confronted with now and in the near future. Some of the challenges are not novel or restricted to midlife, but emerged earlier in life and continue to be evident and are magnified in midlife. The key point is that their intensity, magnitude, or sheer load are increasing because middle-aged adults are often confronted with a myriad of these concurrently, while typically holding responsibility for those younger and older in the family. Of note is also that the load comes at a point in life when vulnerabilities begin to emerge (e.g., onset of chronic disease, cognitive declines). As a consequence, the manifestation of these challenges may be different in midlife compared to young adulthood, in the ways people experience, or enact them. For example, middle-aged adults are often simultaneously balancing caregiving-related duties for aging parents, re-launching their adult children, and maintaining their own career, while dealing (in the US) with a shrinking social safety net in the form of rising healthcare costs and insufficient family leave policies. This balancing and overload of a myriad of roles is transpiring in the context of their own changing mental, physical, and cognitive health, resulting in some middle-aged adults having to put their own health needs and leisure time second.

The sections that follow discuss midlife as a pivotal period given its central role in the life course in relation to those younger (grandchildren and adult children) and older (parents and in-laws). Key themes include the unique constellations of roles and life transitions; opportunities in midlife such as rewards in one’s career; shifting trends in mental and physical health; intergenerational dynamics; and financial vulnerabilities. To begin, we note that very little is known about midlife. Complicating matters, the little that we know is more or less entirely based on US samples that mirror traditional family structures of middle-class people, who are White, married, and have children. To spur research into diversity, we use each theme to discuss similarities and differences in midlife across population segments defined by race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and SES. Admittedly, some of the points made are rather speculative, so we invite others to address and test the points empirically to advance the field.

Midlife as a Pivotal Period

Midlife has recently been conceptualized as a pivotal period in the life course to recognize the central role that midlife plays in the individual life course and the success and development of other people in the family, workplace, community, and society at large (Lachman et al., 2015). Middle-aged adults often play a crucial role in bringing together and nurturing family members and mentoring co-workers. The central position in the life course is captured by balancing gains and losses associated with the aging process, linking earlier and later periods of life, and bridging generations. As shown in Figure 1, the nature of development in midlife is affected by what occurred earlier in life. Empirical research has shown that adversity, parenting styles, and SES in childhood are associated with cognition, mental and physical health, and social relationship quality in midlife (Liu & Lachman, 2019; Miller et al., 2011). In turn, midlife health and well-being often profoundly shape the course of later life. For example, high blood pressure in midlife – but not old age! –predicted old-age cognitive declines (Launer et al., 1995). This perspective on midlife serves as a framework for describing, explaining, and modifying the biopsychosocial experiences in midlife. Health disparities across race/ethnicity, SES, and sexual orientation are often present and magnified in midlife, further signifying the importance of biopsychosocial experiences in midlife (Adler & Rehkopf, 2008; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2018).

Unique Constellations of Simultaneous Roles and Life Transitions

Midlife is only loosely tied to age boundaries, but defined and characterized by the myriad of social roles (broadly defined) that people take on, occupy, and feel responsible for. These roles include, but are not limited to, spouse or partner, parent, grandparent, adult-child, sibling, friend, co-worker, caregiver, community and religious roles. Ahrens and Ryff (2006) documented that adults could be involved with up to eight different roles, with the average individual in midlife being involved in four. The number of role constellations that middle-aged adults navigate and balance differ compared to young adulthood and old age: Older adults likely select themselves into fewer roles due to retirement, health changes, and focusing on emotionally meaningful goals (Carstensen et al., 1999), whereas young adults are in a stage of exploration, establish their career, and start a family (Arnett, 2000), which in turn limits their commitment.

Another unique organizing feature of midlife is the various life transitions people are normatively faced with. These encompass profound changes in everyday life routines in one’s career (e.g., promotion and career advancement, labor market volatility), physical health (e.g., onset of chronic conditions), and social life (e.g., timing of having kid[s]; decision whether to have kids and, if so how many, empty nest). The nature, onset, and duration of midlife is in part driven by the timing of marriage and childbearing. With more people waiting to have children until later in their 30’s and early 40’s (Martin et al., 2017), they are having to care for toddlers and school age-children later and would typically not become empty nesters and grandparents until one’s 60’s or beyond. How the implications of these role constellations overlap with and differ across populations segments (e.g., those who have no partner or children) are by and large not well understood.

Opportunities of Midlife

Although we detail below many challenges associated with the key role of middle-aged adults, there is evidence that midlife has many rewards and positive experiences (Lachman et al., 2015). Figure 1 includes various areas where midlife can be a peak time, such as work position, earnings, family leadership, self-confidence, decision-making abilities, and community contributions. Individuals have presumably moved up the career ladder, resulting in the highest point of earnings occurring, on average, in the late-40s for people with fewer years of education, and the early-50s for people with higher levels of education (Bhuller et al., 2017). Gains are also observed in emotional experience (Carstensen et al., 1999), crystallized abilities (Schaie, 1994), and control beliefs (Lachman, 2006). Middle-aged adults typically become grandparents, leading to opportunities for generativity and multi-generational relationships, such as involvement in the everyday care of their grandchildren (Bengtson, 2001). Opportunities of midlife are societally structured. Higher SES provides access to opportunities such as better quality and more consistent health care, expanded leisure activities, exposure to fewer negative events and chronic strains, and presence of social, financial, and psychological resources (Kirsch et al., 2019). In contrast, these gains do not fully transpire across population segments. For example, disparities are already evident in midlife, with lower levels of and/or reduced gains in episodic memory and executive function among Blacks relative to Whites and among lower SES relative to higher SES (Zahodne et al., 2017). Similar SES differences have been reported for control beliefs (Lachman, 2006). Findings pertaining to whether the observed gains in mental health and well-being are similarly experienced across racial/ethnic groups and SES has documented that Whites have higher rates of depression and anxiety compared to racial/ethnic groups (Chen et al., 2019) and LGBT adults show higher risk of poorer mental health (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013), whereas research has shown that low SES individuals are more vulnerable to poorer mental health (Chen et al., 2019; Ryff, 2017).

Emerging Trends across Mental and Physical Health

Mental health.

A paradoxical finding vis-à-vis the stability in life satisfaction and upward trajectories of emotional experience in midlife is that rates of depression, anxiety, and serious psychological distress are highest in midlife, particularly among women, lower SES individuals, and those who identify as LGBT (Brody et al., 2018; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2018). Correspondingly, antidepressant use and seeing a mental-health professional is highest in midlife (late 40s to early 60s) compared to earlier or later in adulthood and is more pronounced for women and individuals with fewer years of education (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2016).

A consequence of changing mental health trends are historically rising mortality rates for middle-aged adults, in particular deaths from poisoning, suicide, chronic liver disease, and cirrhosis (Case & Deaton, 2015). These trends have been labeled “deaths of despair” and potential reasons (discussed later) include serious difficulties in work, family/home, and social activities as well as ease of access to opioids (Case & Deaton, 2015; Masters et al., 2018).

Physical health.

Similar historical trends have been reported for physical health, with recent cohorts of middle-aged adults having higher prevalence rates for certain chronic illnesses such as metabolic disease (Masters et al., 2018) and increasing disability rates (Chen & Sloan, 2015). Potential explanations include rising rates of obesity, increased calorie intake and reliance on processed foods, low physical activity rates, and large number of individuals who are “under-insured” in the US (Crimmins & Zhang, 2019). Middle-aged adults across affluent nations report more sleep problems, severe headaches, concentration difficulties, and alcohol dependence compared to those in young adulthood and old age (Giuntella et al., working paper). These trends are more pronounced for people who attained fewer years of education (Kirsch et al., 2019), Hispanics and Blacks (Hales et al., 2017), and those who identify as LGBT (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013). Among the long-term consequences of middle-aged adults approaching old age with more chronic diseases, disability, physical inactivity, and obesity are presumably greater health insurance expenses and reliance on family members for caregiving duties.

Intergenerational Dynamics

Historical changes in family composition.

The double-headed arrows between the defining features of midlife and social network composition in Figure 1 exemplify how one key focus of midlife is interacting with and bridging younger and older generations (Lachman et al., 2015). Pew data reveal historical shifts in family composition in midlife: one third of middle-aged adults are unpartnered and one fifth (more than ever) do not have children (Fry, 2017). Additional trends include record numbers of Americans living in multi-generational households, more women giving birth who have never been married, and changes in the gender composition of heads of households (e.g., same-sex couples, transgender spouse[s]). Little is known, however, about whether and how the downward and upward intergenerational dynamics noted generalize across population segments of race/ethnicity, SES, and sexual orientation.

Historical changes in the structure and function of families have impacted relationships of middle-aged adults with their aging parents, including the frequency of assuming a caregiving role, launching and relaunching grown-up children into adulthood, and the upsides and downsides of grandparenting. Among the multitude of underlying factors are the rapid increase in the number of individuals who are living to age 65 and beyond and the changing norms for single parenthood, divorce, and step-parenting that have resulted in remarriages, blended families, and co-habiting families (Antonucci et al., 2011; Bengtson, 2001; Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010). Changes in family composition and dynamics have led to individuals having more and different types of relationships, which have implications for development in midlife (Connidis, 2015). This may include “added” grandchildren as a result of a remarriage and thereby increasing the size of family support networks, whereas a possible downside is losing contact with grandchildren who move away with the custodial parent (Antonucci et al., 2011). Post-divorce families are vulnerable to tensions and ambivalence, which threatens the likelihood and quality of intergenerational care provision (Connidis, 2015). Caregiving for an aging parent can involve shared responsibilities across siblings and spouse/partners that can strain relationships (Aneshenshel et al., 1995). Remarried caregivers, on average, report less emotional and instrumental assistance from adult step-children, with considerable tension and conflict reported (Sherman & Boss, 2007). Although family structure and function are varied, complex, and have changed a great deal, family members remain an important source of social support.

Caregiving for aging parents.

One consequence of the tremendous gains in life expectancy in the 20th century is the increased engagement of middle-aged adults and their aging parents with the lives of each other. To begin with, despite health-related challenges, aging parents continue to engage in support exchanges with middle-aged children, particularly when adult children incur life problems, and such support exchanges are associated with daily well-being and health (Huo et al., 2019; Ryff et al., 1994). Midlife children often report giving more support than parents report receiving across various dimensions of support (Kim et al., 2011; Silverstein et al., 2010; Suitor et al., 2011).

The needs of the aging parent can strain the nature of the relationship, and this trend will presumably not slow down because more and more Baby Boomers will live longer and the absolute number of dementia cases will increase (Feinberg, 2018; Hebert et al., 2013). A recent report found that across the US, Germany, and Italy, most adults feel an obligation towards helping their aging parents (Pew Research Center, 2015). These demographic trends have already led to more middle-aged adults being involved in caregiving-related responsibilities while having to juggle full-time work (Gordon et al., 2012). Informal caregiving for dependent children and/or aging parents while working full-time is referred to as double-and triple-duty caregiving. A 2015 AARP report suggests that 44 million US adults provide unpaid family care to either a child or adult, and 6.5 million adults provide unpaid family care to both; 54% of those providing care are in midlife and 60% are working (AARP, 2015); On average, 2.5 hours per day are spent on unpaid care – time that often interferes with paid work, family time, and sleep.

Caregiving-related duties have implications for middle-aged adults’ health and well-being, future employment status, and retirement income. Double-and triple-duty caregiver’s health and work-life balance affect the care they provide to their loved ones as well as their own work performance because these middle-aged adults have to coordinate their roles, resources, and the management of care (Aneshenshel et al., 1995). Double-or triple-duty caregivers report more work–family conflicts, perceived stress, psychological distress, poorer sleep, poorer partner relationship quality, and utilize more acute-health services than non-caregivers (DePasquale et al., 2016, 2017; Polenick et al., 2016). Their career is impacted by reductions in work hours, changing jobs to a less demanding one, delays in career advancement, early retirement, and quitting one’s job to be a full-time caregiver (Eifert et al., 2016; Feinberg, 2018). Daughters and spouses are more likely to provide support to aging parents (Johnson & Weiner, 2006). In the US, Black and Hispanic caregivers are more likely to be co-residents, spend more hours providing care, and use less formal support services compared to White caregivers (Johnson & Weiner, 2006). LGBT middle-aged adults are confronted with elevated risks, including discrimination, identity concealment, and unique family structures that may constitute added barriers to receiving and providing high-quality caregiving (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2018).

Changing relationships with adult children.

The relationships that middle-aged adults have with their grown adult children is undergoing historical changes in the form of increased (1) contact between generations, (2) continued support from parents to grown children, and (3) coresidence and affection (see Fingerman, 2017). The frequency of contact between parents and grown children has increased over the last 30 years, likely due to advances in technology (e-mail, phone, text; Fingerman et al., 2012). Middle-aged adults have more contact with adult children who have problems and are providing more support to them (Huo et al., 2019). Regardless of how successful other children in the family are, when one grown child experiences problems, this often has long-term consequences for midlife parents, including diminished relationship quality, worry and stress surrounding the child, and beliefs that they failed in their parenting role (Byers et al., 2008; Fingerman et al., 2012).

As a corollary, the nature of parenting has evolved, especially in the realm of pressures, involvement, and costs for raising children. Trends of increasing pressures for students to excel in the classroom and overinvolvement in extracurricular activities has elevated their risk for substance use and internalizing/externalizing symptoms (Ebbert et al., 2019;Vincent & Maxwell, 2016). Parents are contending with increasing costs of raising children through expensiveness of daycare, pressures for involvement in extracurricular activities, and saving for college. This has led to growing attention to “helicopter” and “bulldozer” parents or “tiger moms”, who orchestrate their children’s lives and protect against the experience of any hardships or disappointments for their adult children (Ebbert et al., 2019). Greater involvement, coupled with prolonged educational attainment, may be associated with greater reliance of grown adult children on their midlife parents (Settersten & Ray, 2010). More grown adult children nowadays are living with midlife parents compared to 10 years ago (Fry, 2015) before the Economic Recession of 2008. In the US, parents can retain children on their health insurance until age 26 and an increasing number of parents are involved in college processes and co-signing of loans. A drawback of taking on the risk of a co-signer of student loans is that the debt can increase overall financial risk by competing with other needs: saving for retirement, mortgage payments, and being liable for paying off the loans if children are unable to (Walsemann & Ailshire, 2017). Parental overinvolvement and education pressures provide people who have more financial resources with the advantage of taking care of the costs of childcare and extracurricular activities, but adolescents raised in affluence typically have greater substance use rates and mental health issues (Ebbert et al., 2019). Blacks, Hispanics, and low SES individuals typically have less access to school activities, sports, and more likely rely on families for childcare (Vincent & Maxwell, 2016). Greater child-related educational debt was reported by parents with more education, higher income, and Black parents (Walsemann & Ailshire, 2017).

The upsides and downsides of grandparenting.

There is tremendous heterogeneity in the frequency and type of grandparent involvement, ranging from rare interactions over occasional babysitting to custodial grandparenting (Meyer & Kandic, 2017). For a variety of reasons, such relationships are increasingly important to individuals and families. Among the upsides of grandparenting is that it offers people the opportunity to engage in fulfilling family functions, helping behaviors, and provides meaning and purpose and is key to maintaining quality of life (Bengston, 2001; Hilbrand et al., 2017). Grandparents who are retired may be involved with childcare for their grandchildren or help if their grown child is divorced or travels for work, which can reduce costs and potential burdens. Findings indicate an inverse U-shaped association between grandparenting and positive benefits (Coall & Hertwig, 2010). Balancing the correct amount of intensity and frequency can prove beneficial for cognitive functioning, quality of life, physical health, and longevity (Arpino & Bordone, 2014).

One potential downside of grandparenting is when it is full-time, such as when one of the grandparents takes on primary custody of the grandchild(ren). Reasons for custodial grandparenting are widespread, ranging from parents having to work longer hours to crises among the birth parents (e.g., substance use, incarceration, mental and physical illness, and child abuse/neglect). Although custodial grandparents contribute tremendously to society by providing care, the circumstances leading to care combined with the stress of full-time parenting have profound physical, psychological, and social effects on both custodial grandparents and grandchildren (Meyer & Kandic, 2017). In contrast to grandparenting for the “right” amount of time (i.e., middle of the U-shape), stressors faced by custodial grandparents include financial strain, insufficient social support, lifestyle disruption, and disregard by service providers (Meyer & Kandic, 2017). Multiple studies corroborate that those raising a grandchild were more likely to report worse mental and physical health and more activity limitations than non-caregivers (Hayslip et al., 2017). Likelihood of involvement in grandparenting differs across SES and race/ethnicity. Individuals in lower SES strata and Blacks and Hispanics are more likely to be custodial grandparents (Hayslip et al., 2017), with the rates increasing for Whites because of substance abuse (Alexander et al., 2018) and military deployment (Bunch et al., 2007).

Financial Vulnerabilities

Career development, employment, and financial stability are central to midlife. Their significance is exemplified through extant findings that work-related factors such as occupational class, work hazards, and work complexity predict mental and physical health, cognition, and longevity in midlife and old age (Fisher et al., 2014; Hueluer et al., in press; Super, 1990). Our discussion of financial vulnerabilities focuses on middle-aged adult’s sensitivity to economic failures, employment (in)stability, and shrinking social and healthcare safety net.

Economic failures and labor market volatility.

Findings obtained in the aftermath of the Economic Recession of 2008 in the US illustrate that middle-aged adults are presumably most vulnerable to economic failures and labor market volatility. Circumstances surrounding the recession included multiple hardships rather than a stand-alone event: Housing and financial conditions plummeted, retirement accounts were depleted, and unemployment rates soared (Burgard & Kalousova, 2015). This led to job insecurity, financial strain, stagnant wages, more frequent and longer phases of unemployment, and increased debt (Burgard & Kalousova, 2015). To illustrate, between 2008 and 2013, 25% of Americans aged 50 to 59 and 20% of those aged 60 to 64 lost a job and – due in part to ageism and age discrimination – they often had difficulty finding new jobs (AARP, 2014). Despite legislation, age discrimination is a continued problem, which can impede employment opportunities, career advancement and have consequences for mental and physical health and overall quality of life (Rothenberg & Gardner, 2011). This labor market volatility extends to individual’s perceptions of job (in)security: 24% of people aged 45–74 thought they could lose their job in the next year (Moen, 2016). The economic downturn also led to an increased likelihood of individuals working beyond age 62 (Goda et al., 2011).

Labor market volatility and the economic recession had adverse effects on mental and physical health and family relationships. For example, job loss was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms both in the US and Europe (Riumallo-Herl et al., 2014). During periods of economic recession, there is a higher prevalence of mental health and substance disorders and suicidal behavior, with one key mechanism being declines in household income (Frasquilho et al., 2016). Recession hardships directly linked to job (taking an additional job), home (missed payments) and financial matters (increased debt) were associated with reporting more chronic conditions and acute somatic symptoms, lower self-rated health, and higher waist circumference (Kirsch & Ryff, 2016). Long-term consequences of fluctuations in economic hardships in midlife can even extend to cognition in old age (Leist et al., 2014). More generally, long-term cyclical effects of job insecurity, financial loss, bankruptcy, and home repossession can lead to anxiety, depression, binge drinking, and suicidal behavior (Haw et al., 2015; Phillips & Nugent, 2014).

Empirical studies have also shown how economic pressure and hardships of their adult children undermine the health and well-being of middle-aged parents. Middle-aged parents’ concerns about their adult children’s economic future was directly associated with higher levels of anxiety and depressed mood (Stein et al., 2011). This was driven by the lack of employment opportunities and inability to meet material needs, such as lack of health insurance (due to job loss) that impacts one’s ability to manage chronic conditions (Rajmil et al., 2014). Middle-aged parents have to contend with a continued or renewed dependency of their adult children, including them returning to live with them (Stein et al., 2013; Ward & Spitze, 2007).

Specific population segments are hit harder than others: those who lost their job due to an unexpected closure, low-to-middle SES families, and midlife parents of a child with disability were most impacted by unemployment during the 2008 recession (Lam et al., 2014; Riumallo-Herl et al., 2014; Song et al., 2018). Women, particularly of color, are among those most vulnerable to poor mental and physical health and report being most financially vulnerable to labor market volatility (Baker et al., 2019; Kirsch & Ryff, 2016; Wang et al., 2018). Following Wahl and Gerstorf’s notion (2018) that immediate and distal contexts shape development and do so in interactive ways, the impact of the economic recession on suicide rates was strongest in US counties with high levels of poverty, foreclosures, and unemployment (Kerr et al., 2017).

Shrinking social and healthcare safety net.

In the US, labor market volatility and economic failures contribute to a shrinking social and healthcare safety net for middle-aged adults. Middle-aged adults typically have families that rely on them for healthcare and financial security, with restricted access to and increases in healthcare costs being burdensome. Health care costs are growing faster than inflation and out-of-pocket spending is sizeable and increasing (Paez et al., 2009; Woolhandler & Himmelstein, in press). Less comprehensive health insurance benefits can lead to anxiety, substantial debt problems, and disruptions of medical care (i.e., less adherence to disease management; Grande et al., 2013). Such sequences can threaten household budgets pertaining to food, housing, and access to social activities (Salamon et al., 2009).

The shrinking safety net is most striking for middle-aged adults who are taking on caregiving responsibilities for their aging parents. Feinberg (2018) noted the profound lack of paid family-leave policies that pertain to family caregivers providing unpaid assistance to family members needing long-term services. These people are at major risk for economic insecurity and declines in mental and physical health. Individuals who work while caregiving typically take reduced hours at work, take a less demanding job, take early retirement, or decide between caregiving and work (Komisar, 2013). This disproportionally affects women (who are more likely to provide care) and lower SES individuals compared to those with higher income who can hire help or afford to place their aging relative into a care facility (Aneshenshel et al., 1995).

Policies are not setup for middle-aged caregivers, but the number of those involved in unpaid caregiving will increase in the future. In the US, only six States and DC have extended paid family leave policies specifically for caregiving for an adult relative. Depending on the State, these policies can include having up to 12 weeks of paid time off with wage replacement between 50–80% of one’s salary (Feinberg, 2018). Although this may seem helpful, it is often those who cannot afford to take a wage cut who have to take on caregiving responsibilities.

Another byproduct of the shrinking safety net is the growing rate of bankruptcy for middle-aged adults. Individuals age 45 and older have the fastest growing rate of bankruptcy (Thorne et al., 2018). This is driven by rising debt from greater cost-sharing pertaining to healthcare and medication costs and co-signing student loans. Although significant progress has been made in health care coverage and delivery of services, there is ongoing debate on ways to manage growing costs while providing widespread coverage. Policy makers should consider the consequences of high cost sharing for families facing strained household budgets. Rising inflation and out-of-pocket healthcare expenses, coupled with stagnant wages and employment instability, will lead to people explicitly ranking bill-paying priorities, often beginning with housing costs and involving compromises on utilities, health care (i.e., delay life-saving procedures and skips in medications), transportation, and food (Grande et al., 2013).

Promoting Reversibility and Resilience in Midlife

Middle-aged adults are faced with juggling multiple responsibilities that may lead to overload and stress when trying to handle it all. Middle-aged adults are contending simultaneously with multiple roles and life transitions; changes in family composition and dynamics with both older and younger generations; financial strains due to labor market volatility and a shrinking social safety net; and a historical high in the prevalence of mental and physical health issues. Midlife can also be a peak time in many areas, including earnings, position at work, leadership in the family, decision-making abilities, self-confidence, control beliefs, and contributions to the community (Lachman et al., 2015).

Because middle-aged adults comprise a large component of the population, they are carrying much of the weight of our economy, and their productivity, health, and well-being influence many others. Now that we have illustrated the central opportunities and challenges surrounding midlife, we next discuss the grand task of configuring effective solutions using interventions and policy changes for promoting the mental and physical health and capacity for resilience in middle-aged adults. We propose several promising ways interventions and policy can help further support and promote the lives of middle-age adults. Given the complex nature of midlife, interventions and policy changes should span the multiple levels shown in Figure 1 by not only targeting changes that can be implemented by the individual, but also opportunities for support and engagement though one’s social network composition, as well as what can be done at the macro level of workplace organizational structure and policy changes. In this context, interventions need to be cognizant of disparities across race/ethnicity, SES, and sexual orientation. As discussed above, segments of the US population are disproportionally impacted by the challenges of midlife. Resilience is broadly defined as positive adaptation in the context of the challenges middle-aged adults are confronting (Infurna & Luthar, 2018).

Interventions to Improve Physical Health

Numerous empirical studies have documented that better health in midlife is a precursor for health in old age. Being more physically active, greater muscle strength, and healthy blood pressure in midlife were each predictive of better physical and mental health, cognition, and longevity in old age (Launer et al., 1995; Rantanen et al., 2012). Midlife social, health, and lifestyle activities foreshadow many old age outcomes. Interventions focused on promoting physical activity and engagement in midlife promise to help people reach old age healthier, reduce the trends of increasing chronic illness and poor health behavior prevalence, and promise to reduce societal costs and increase individual quality of life.

Several interventions have been effective in promoting an active lifestyle in middle-aged adults. One such intervention capitalized on implementation intentions to promote physical activity (Robinson et al., 2019). This involved identifying potential barriers to being active, providing resources to help individuals take control of their daily schedule, managing time-related barriers to exercise, and incorporating physical activity into daily life routines. Individuals in the intervention condition took more daily steps, had more time spent in moderate-to-vigorous activity, and reported greater time-relevant exercise self-efficacy. Another intervention capitalized as an avenue for promoting physical activity on people’s views of aging—the knowledge, beliefs, and expectations an individual holds about aging processes (Brothers & Diehl, 2017). The program involved an educational component targeting behavioral intentions and a second component translating the intention into actual behavior. The program indeed led to improvements in views of aging, control beliefs, and physical activity.

Interventions to Reduce Caregiving-Related Stress

Middle-aged adults are taking on caregiving responsibilities for their aging parents and children (with disabilities or illnesses). Research has documented the detrimental consequences of caregiving on mental and physical health (Aneshenshel et al., 1995). Fortunately, there is a rich literature on interventions aimed at reducing caregiving-related stress, ranging from social support, education, skills training, and self-care (Schulz & Martire, 2004). Utilization of adult day care services reduces exposure to stressors and stress appraisals, leading to better mood, physiological functioning, and reductions in behavioral symptoms of the care recipient (Klein et al., 2016; Zarit et al., 2011). Adult day care services allow caregivers respite from the primary stressors associated with caregiving (Gitlin et al., 2015). Multi-component interventions that involve individual sessions delivered at home or through the telephone, supplemented by support-group sessions have led to reductions of hours providing care, improvements in quality of life as well as incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for caregivers across racial/ethnic groups (Belle et al., 2006; Nichols et al., 2008). Puterman and colleagues (2018) conducted an RCT that examined the effectiveness of aerobic exercise for dementia caregivers who were sedentary, finding improvements in physiological functioning and declines in perceived stress.

Intervention delivery methods vary from support groups to being telephone-and internet-based. A recent systematic review of internet-based supportive interventions for caregivers found that internet interventions for dementia caregivers can improve various aspects of caregiver well-being, provided these comprise multiple components and are tailored to the individual (Boots et al., 2014). Initial findings are promising, but much is still to be done to translate and incorporate effective interventions into policy and healthcare (for discussion, see Gitlin et al., 2015). This is shown by caregivers who contend with structural burdens due to difficulties attaining the proper informational resources, dealing with a fragmented system between care providers who do not interact with one another, and ensuring their loved one receives proper care (Funk et al., 2019).

Interventions to Improve Mental Health through Social Engagement

Interventions aimed at social support and engagement have the potential to mitigate stress (Infurna & Luthar, 2018) caused by changing intergenerational dynamics and financial vulnerabilities. Social support and relationships have a long-documented history of being a source of resilience for individuals confronting adversity (Luthar et al., 2000). During times of need, individuals can draw upon members of their network for emotional, informational, or instrumental support, each showing unique protective benefits across different contexts (Infurna & Luthar, 2018). Social support and engagement are found to be malleable through intervention. Castro and colleagues (2019) tested the effectiveness of a social intelligence training program that was delivered online to help middle-aged adults connect with others through building socio-emotional skills. Using an RCT design, they found significant improvements in social engagement, perspective-taking, and emotional awareness across midlife participants in the treatment condition and improvements were stronger for those who experienced childhood trauma. Findings shed light on the potential reversibility of socio-emotional mechanisms that are often times viewed as mechanisms leading to mental and physical health in midlife, and support the utility of widely accessible, low-cost intervention methods. Another intervention aimed at fostering resilience among professional women at high risk for stress and burnout (e.g., health care providers who are mothers) by focusing on aspects of support, prioritizing, mothering, and self-compassion (Luthar et al., 2017). Using an RCT design, improvements in depression, self-compassion, feeling loved, physical affection received, and parenting stress were documented. More generally, the authors discuss how tools facilitated colleague support groups could be viable, low-cost preventive interventions to mitigate burnout and distress for at-risk groups.

Policy Changes

Policy changes pertaining to the work-family nexus and shrinking safety net promise to help middle-aged adults accommodate some of the challenges of midlife. Few paid family leave policies exist in the US for individuals wanting to provide care for an aging parent or stay at home for an extended period following childbirth, making it difficult to balance work, oftentimes needing to choose between work and caregiving. For example, Juengst and colleagues (2019) studied physician mothers’ family leave and return-to-work experiences and found that a majority of mothers were confused regarding their employer leave policies and felt that their leave time was insufficient. Furthermore, participants encountered numerous difficulties when returning to work, such as lack of facilities and inadequate time for breast pumping, difficulty obtaining childcare, feeling pressured to return to work prematurely and experiencing discrimination for having taken maternity/family leave. European nations have established systems for paid time off to new parents, child and healthcare. Glass and colleagues (2016) found that in countries providing social welfare benefits to parents, on average, they are more likely to exhibit higher well-being. Beckfield and Bambra (2016) found that a lack of such policies accounts for 3.77 years of lost life expectancy. Feinberg (2018) outlined various ways to improve paid family leave policy. Workers can be provided access to sick days and paid family leave, which can lessen caregiving strain, providing family caregivers with greater financial security, increase employee retention, and help maintain a productive workforce. Additional suggestions include cost-sharing programs among employees and employers that would operate similar to a 401k program, but for paid-time off pertaining to family leave. This could operate through the employees contributing a percentage of their salary and the employer matching this with the expectation that this fund is designated only towards paid time off for family leave.

Workplace flexibility can promote health, well-being, and workplace performance for middle-aged adults. Kelly and colleagues (2011) tested a corporate initiative promoting employees’ schedule control and loosening work-time calendars, which improved health-related behaviors, sleep quality, work-family conflict, and well-being. Kossek and colleagues (2019) tested an organizational intervention designed to increase supervisor social support and job control; the intervention was most effective in reducing psychological distress for double-duty and triple-duty caregivers. Flexibility through organizational structures and interventions that increase job resources can lower turnover intentions, reduce work-to-family and family-to-work conflicts, and improve individual and family mental and physical health (Moen, 2016).

Education is often seen as the purview of the young, but given the rapid technological change, it is critical for middle-aged adults to continually be engaged with learning so as to reduce obsolescence and maintain critical work skills. Many companies offer retraining of employees and those in midlife are prime candidates for enriching their repertoire so as to remain valuable as a worker but also to engage in cognitively stimulating activities that can have positive benefits for one’s own cognitive aging.

Conclusion

The narrative surrounding midlife is shifting in the context of changes in the timetables of younger adults, the health span of older adults, and the historical changes seen in social, cultural, and economic life arenas. Given the decrease in the number of children being born and the increasing number of older people, middle-aged adults are more relevant than ever before as a significant resource for families and society. To the extent that middle-aged adults are successful and productive, then their families and the society as a whole will be the beneficiaries. The reverse is true as well: If the well-being of those in midlife is threatened rather than protected, the repercussions could reverberate throughout families and society.

Some of what we know about midlife is based on misconceptions and some narratives have been debunked by empirical research. We have discussed opportunities and challenges those in midlife are confronted with, which we hope will stimulate future research, interventions, and policies related to this largely unchartered yet pivotal period of the lifespan. Future endeavors can focus on historical shifts in the mental and physical health and family composition amongst middle-aged adults, the changing intergenerational dynamics with grown adult children and aging parents, and the financial vulnerabilities associated with economic failures, labor market volatility, and a shrinking safety net. Multiple time-scale designs (Gerstorf et al., 2014) can be used to study the nature and correlates of how daily-life dynamics (e.g., intergenerational interactions) change as people move through life transitions (e.g., one partner takes on caregiving responsibilities for an aging parent or is having to deal with re-positioning at work). For example, Huo and colleagues (2019) tracked middle-aged adults and their aging parents over the course of seven days to study support exchanges and their impact on daily well-being. Combining multiple sources of information, including self-and informant-reports, qualitative data through semi-structured interviews, performance-based measures, and dyadic approaches (e.g., partners, children, co-workers) can further enhance our ability to study opportunities and challenges of midlife (e.g., spillover of workplace stressors to the family: Moen, 2016).

In future research, concerted efforts need to be taken to better understand diversity in how midlife is experienced differently across race/ethnicity, SES, and sexual orientation. This is along the lines of the initiative of the National Institute on Aging to specifically investigate and showcase priorities and investments in health disparities research. Similarly, Kirsch and colleagues (2019) observed that middle-aged adults in the US after the economic recession reported more financial insecurity, worse physical health, and more impoverished well-being than same-aged peers before the economic recession, particularly among those who attained fewer years of education. Based on these findings and our review of the literature, it is evident that the challenges confronting middle-aged adults are disproportionally impacting minorities, people in lower socioeconomic strata, and those who identify as LGBT. It thus seems imperative to move ahead from studying middle-class, college-educated White midlife adults who often have adequate financial, social, and psychological resources towards also studying the large populations at risk. This includes middle-aged adults who experience extraordinary challenges such as raising a child with a disability or illness; financially supporting and providing care for ailing parents; dealing with physically or mentally ill spouses; working multiple jobs to get by because of strained household budgets, or addressing their own declining health. Such conceptual and empirical lines of inquiry promise to shed light onto commonalities and differences across population segments in the opportunities and challenges of midlife as well as the resilience factors people draw from, and thereby inform tailored prevention and intervention efforts.

Avenues for intervention to promote resilience among middle-aged adults include improving health through physical activity, reducing caregiving stress, improving mental health through social support and engagement, and adopting policies pertaining to the shrinking social safety net. A focus on optimizing the well-being of those in midlife can have far-reaching effects on those younger and older who depend on them.

Public Significance:

Middle-aged adults are facing unprecedented societal challenges, but scientifically, midlife remains largely uncharted territory. We outline and discuss opportunities and challenges middle-aged adults are confronted with, including changes in relationships of middle-aged adults with their aging parents, adult children and grandchildren as well as vulnerabilities that emerge from economic failures, labor market volatility, and a shrinking social and healthcare safety net, which operate in the context of historical shifts in mental and physical health and family composition. We discuss interventions and policy changes to help promote reversibility and resilience among middle-aged adults to meet the unprecedented challenges.

Acknowledgments

Frank J. Infurna gratefully acknowledges the support provided by the John Templeton Foundation (Grant #60699). Denis Gerstorf gratefully acknowledges the support provided by the German Research Foundation (DFG, GE 1896/3–1; GE 1896/6–1; and GE 1896/7–1). Margie E. Lachman gratefully acknowledges the support provided by National Institute on Aging Grants PO1 AG020166, U19 AG051426, and P30 AG048785. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Biography

References

- AARP (2014). Staying Ahead of the Curve 2013: AARP Multicultural Work and Career Study: Older Workers in an Uneasy Job Market. Washington, DC: AARP. [Google Scholar]

- AARP (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. Washington, DC: AARP. [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, & Rehkopf DH (2008). U.S. Disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 235–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens CJC, & Ryff CD (2006). Multiple roles and well-being: Sociodemographic and psychological moderators. Sex Roles, 55(11–12), 801–815. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander MJ, Kiang MV, & Barbieri M. (2018). Trends in Black and White Opioid Mortality in the United States, 1979–2015. Epidemiology, 29, 707–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshenshel CS, Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Zarit SH, & Whitlatch CJ (1995). Profiles in caregiving: The unexpected career. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Birditt KS, Sherman CW, & Trinh S. (2011). Stability and change in the intergenerational family: A convoy approach. Ageing & Society, 31, 1084–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teends through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpino B, Bordone V, 2014. Does grandparenting pay off? The effect of child care on grandparents’ cognitive functioning. J. Marriage Fam 76, 337e351. [Google Scholar]

- Baker AC, West S, & Wood A. (2019). Asset depletion, chronic financial stress, and mortgage trouble among older female homeowners. The Gerontologist, 59, 230–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird BM, Lucas RE, & Donnellan MB (2010). Life Satisfaction Across the Lifespan: Findings from Two Nationally Representative Panel Studies. Social Indicators Research, 99(2), 183–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23(5), 611–626. [Google Scholar]

- Beckfield J, Bambra C. 2016. Shorter lives in stingier states: Social policy shortcomings help explain the US mortality disadvantage. Soc. Sci. Med 171:30–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL (2001). Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuller M, Mogstad M, Salvanes KG (2017). Life-cycle earnings, education premiums, and internal rates of return. Journal of Labor Economics 35, 993–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2016). Antidepressants and age: A new form of evidence for U-shaped well-being through life. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 127, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, & Kessler RD (2004). How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brody DJ, Pratt LA, Hughes J. Prevalence of depression among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 2013–2016 NCHS Data Brief, no 303. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothers A, & Diehl M. (2017). Feasibility and efficacy of the AgingPlus program: Changing views on aging to increase physical activity. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 25, 402–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunch SG, Eastman BJ, & Moore RR (2007). A profile of grandparents raising grandchildren as a result of parental military deployment. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, & Kalousova L. (2015). Effects of the Great Recession: Health and Well-Being. 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Byers AL, Levy BR, Allore HG, Bruce ML, & Kasl SV (2008). When parents matter to their adult children: Filial reliance associated with parents’ depressive symptoms. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, P33–P40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, & Charles ST (1999). Taking Time Seriously. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, & Deaton A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. PNAS, 112, 15078–15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Kessler RC, Sadikova E, Nemoyer A, Sampson NA, Alvarez K. … & Williams DR (2019). Journal of Psychiatric Research, 119, 48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sloan FA (2015) Explaining disability trends in the U.S. elderly and near-elderly population. Health Services Research, 50, 1528–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coall DA, & Hertwig R. (2010). Granparental investment: Past, present, and future. Behavioral Brain Sciences, 33, 1–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePasquale N, Davis KD, Zarit SH, Moen P, Hammer LB, & Almeida DM (2016). Combining formal and informal caregiving roles: The psychosocial implications of double-and triple-duty care. Journals of Gerontology-Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePasquale N, Polenick CA, Davis KD, Moen P, Hammer LB, & Almeida DM (2017). The Psychosocial Implications of Managing Work and Family Caregiving Roles: Gender Differences Among Information Technology Professionals. Journal of Family Issues, 38(11), 1495–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbert AM, Kumar NL, & Luthar SS (2019). Complexities in adjustment patterns among the “best and the brightest”: Risk and resilience in the context of high achieving schools. Research in Human Development, 16, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Eifert EK, Adams R, Morrison S, & Strack R. (2016). Emerging Trends in Family Caregiving Using the Life Course Perspective: Preparing Health Educators for an Aging Society. American Journal of Health Education, 47(3), 176–197. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1993). Childhood and society. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF (2018). Breaking new ground: Supporting employed family caregivers with workplace leave policies. Insight on the issues, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Pillemer KA, Silverstein M, & Suitor JJ (2012). The Baby Boomers’ intergenerational relationships. Gerontologist, 52(2), 199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL (2017). Millennials and Their Parents: Implications of the New Young Adulthood for Midlife Adults. Innovation in Aging, 1(3), 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GG, Stachowski A, Infurna FJ, Grosch J, Faul JD, & Tetrick LE (2014). Mental work demands, retirement, and longitudinal trajectories of cognitive functioning. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(2), 231–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasquilho D, Matos MG, Salonna F, Guerreiro D, Storti CC, Gaspar T, & Caldas-De-Almeida JM (2016). Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: A systematic literature review Health behavior, health promotion and society. BMC Public Health, 16(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Jen S, Bryan AEB, & Goldsen J. (2018). Cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease, and other dementias in the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) older adults and their caregivers: Needs and competencies. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37, 545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim J-J, Barkan SE, Muraco A, & Hoy-Ellis CP (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a Population-Based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 1802–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry R. (2015). More millennials living with family despite improved job market. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Fry R. (2017). The share of Americans living without a partner has increased, especially among young adults. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; Retrieved from http://pewrsr.ch/2kG037Q [Google Scholar]

- Funk LM, Dansereau L, & Novek S. (2019). Carers as system navigators: Exploring sources, processes and outcomes of structural burden. The Gerontologist, 59, 426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Fang S, Krahn HJ, Johnson MD, & Lachman ME (2015). Up, not down: The age curve in happiness from early adulthood to midlife in two longitudinal studies. DP, 51, 1664–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Hoppmann CA, & Ram N. (2014). The promise and challenges of integrating multiple time-scales in adult developmental inquiry. RHD, 11, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Marx K, Stanley IH, & Hodgson N. (2015). Translating evidence-based dementia caregiving interventions into practice: State-of-the-science and next steps. Gerontologist, 55, 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuntella O, McManus S, Mujcic R, Powdthavee N, Oswald AJ, & Tohamy A. (working paper). Why is there so much midlife distress in affluent nations? [Google Scholar]

- Glass J, Simon RW, & Andersson MA (2016). Parenthood and happiness: Effects of work-family reconciliation policies in 22 OECD countries. American Journal of Socioogy, 122, 886–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda GS, Shoven JB, Slavov SN. 2011. What explains changes in retirement plans during the Great Recession? Am. Econ. Rev 101:29–34 [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JR, Pruchno RA, Wilson-Genderson M, Murphy WM, & Rose M. (2012). Balancing caregiving and work: Role conflict and role strain dynamics. Journal of Family Issues, 33, 662–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande D, Barg FK, Johson S, & Cannuscio CC (2013). Life Disruptions for Midlife and Older Adults. Annals of Family Medicine, 11(1), 37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016 NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haw C, Hawton K, Gunnell D, & Platt S. (2015). Economic recession and suicidal behaviour: Possible mechanisms and ameliorating factors. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61, 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayslip B, Fruhauf CA, & Dolbin-MacNab ML (2017). Grandparents raising grandchildren: What have we learned over the past decade?. The Gerontologist, 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, & Evans DA (2013). Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology, 80, 1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbrand S, Coall DA, Gerstorf D, & Hertwig R. (2017). Caregiving within and beyond the family is associated with lower mortality for the caregiver. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38, 397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Hueluer G, Ram N, Willis SL, Schaie KW, & Gerstorf D. (in press). Cohort differences in cognitive aging: The role of perceived work environment. Psychology and Aging. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo M, Graham JL, Kim K, Birditt KS, & Fingerman KL (2019). Aging Parents’ Daily Support Exchanges with Adult Children Suffering Problems. Journals of Gerontology-Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(3), 449–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infurna FJ, & Luthar SS (2018). Re-evaluating the notion that resilience is commonplace: A review and distillation of directions for future research, practice, and policy. Clinical Psychology Review,65, 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaques E. (1965). Death and the midlife crisis. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 46, 502–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Moen P, & Tranby E. (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review, 76, 265–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Caetano R, Giesbrecht N, & McFarland BH (2017). Economic recession, alcohol and suicide rates: Comparative effects of poverty, foreclosure and job loss. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52, 469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch JA, Love GD, & Radler BT, & Ryff CD (2019). Scientific imperatives via-a-vis growing inequality in America. American Psychologist, 74, 764–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch JA, & Ryff CD (2016). Hardships of the great recession and health: Understanding varieties of vulnerability. Health Psychology Open, 3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein LC, Kim K, Almeida DM, Femia EE, Rovine MJ, & Zarit SH (2016). Anticipating an easier day: Effects of adult day services on daily cortisol and stress. Gerontologist, 56, 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komisar H. (2013). The Effects of Rising Health Care Costs on Middle-Class Economic Security. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (2004). Development in Midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 305–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (2015). Mind the gap in the middle: A call to study midlife. RHD, 12, 327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (2006). Perceived control over aging-related declines: Adaptive beliefs and behaviors. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 282–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, & James JB (1997). Multiple paths of midlife development. Chicago: UC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Teshale S, & Agrigoroaei S. (2015). Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: Balancing growth and decline at the crossroads of youth and old age. IJBD, 39, 20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Curlee A, Tye SJ, Engelman JC, & Stonnington CM (2017). Fostering resilience among mothers under stress: “Authentic Connections Groups” for medical professionals. Women’s Health Issues, 27, 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leist AK, Hessel P, & Avendano M. (2014). Do economic recessions during early and mid-adulthood influence cognitive function in older age? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68, 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson DL (1986). A conception of adult development. American Psychologist, 41, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. & Lachman ME (2019). Socioeconomic status and parenting style form childhood: Long-term effects on cognitive function in middle and ltaer adulthood. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2016 NCHS data brief, no 287. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters RK, Tilstra AM, & Simon DH (2018). Explaining recent mortality trends among younger and middle-aged White Americans. International Journal of Epidemiology, 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP & de. St. Aubin E. (1992). A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. JPSP, 62, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MH & Kandic A. (2017). Grandparenting in the United States. Innovation in Aging, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Lachman ME, Chen E, Gruenewald TL, Karlamangla AS, & Seeman TE (2011). Pathways to resilience: Maternal nurturance as a buffer against the effects of childhood poverty on metabolic syndrome at midlife. Psychological Science, 22, 1591–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell BA (2006). The boomerang age Transitions to adulthood in families. New Jersey: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Moen P. (2016). Encore adulthood: Boomers on the edge of risk, renewal, and purpose. New York:OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols LO, Chang C, Lummus A, Burns R, Martindale-Adams J, Graney MJ, … Czaja S. (2008). The cost-effectiveness of a behavior intervention with caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(3), 413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez KA, Zhao L, & Hwang W. (2009). Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: A ten-year trend. Health Affairs, 28(1), 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2015). Family Support in Graying Societies. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA, & Nugent CN (2014). Suicide and the Great Recession of 2007–2009: The role of economic factors in the 50 U.S. states. Social Science and Medicine, 116, 22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polenick CA, DePasquale N, Eggebeen DJ, Zarit SH, & Fingerman KL (2016). Relationship Quality Between Older Fathers and Middle-Aged Children: Associations With Both Parties’ Subjective Well-Being. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puterman E, Weiss J, Lin J, Schilf S, Slusher AL, Johansen KL, & Epel ES (2018). Aerobic exercise lengthens telomeres and reduces stress in family caregivers: A randomized controlled trial-Curt Richter Award Paper 2018. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 98, 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajmil L, de Sanmamed MJF, Choonara I, Faresjö T, Hjern A, Kozyrskyj A, … Taylor-Robinson D. (2014). Impact of the 2008 economic and financial crisis on child health: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11, 6528–6546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, Masaki K, He Q, Ross GW, Willcox BJ, & White L. (2012). Midlife muscle strength and human longevity up to age 100 years: A 44-year prospective study among a decedent cohort. Age, 34, 563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riumallo-Herl C, Basu S, Stuckler D, Courtin E, & Avendano M. (2014). Job loss, wealth and depression during the Great Recession. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SA, Bisson AN, Hughes ML, Ebert J, & Lachman ME (2019). Time for change: using implementation intentions to promote physical activity in a randomised pilot trial. Psychology and Health, 34, 232–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg JZ, & Gardner DS (2011). Protecting older workers: The failure of the age discrimination in employment act of 1967. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 38, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD (2017). Eudaimonic well-being, inequality, and health: Recent findings and future directions. International Review of Economics, 64, 159–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]