Abstract

Circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) can be taken up by recipient cells and have been recently associated with the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Their role in host predisposition to the syndrome is unknown. The objective of the study was to identify circulating miRNAs associated with the development of sepsis-related ARDS and examine their impact on endothelial cell gene expression and function. We determined miRNA levels in plasma collected from subjects during the first 24 h of admission to a tertiary intensive care unit for sepsis. A miRNA that was differentially expressed between subjects who did and did not develop ARDS was identified and was transfected into human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMECs). RNA sequencing, in silico analysis, cytokine expression, and leukocyte migration assays were used to determine the impact of this miRNA on gene expression and cell function. In two cohorts, circulating miR-887-3p levels were elevated in septic patients who developed ARDS compared with those who did not. Transfection of miR-887-3p into HPMECs altered gene expression, including the upregulation of several genes previously associated with ARDS (e.g., CXCL10, CCL5, CX3CL1, VCAM1, CASP1, IL1B, IFNB, and TLR2), and activation of cellular pathways relevant to the response to infection. Functionally, miR-887-3p increased the endothelial release of chemokines and facilitated trans-endothelial leukocyte migration. Circulating miR-887-3p is associated with ARDS in critically ill patients with sepsis. In vitro, miR-887-3p regulates the expression of genes relevant to ARDS and neutrophil tracking. This miRNA may contribute to ARDS pathogenesis and could represent a novel therapeutic target.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, chemokines, leukocytes, microRNAs, sepsis

INTRODUCTION

The acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a major public health threat occurring in up to 10% of critically ill patients worldwide while resulting in high morbidity and mortality rates (8). ARDS is characterized by a complex phenotype of epithelial injury, endothelial dysfunction, and immune cell trafficking, ultimately leading to alveolar edema and respiratory failure (51). Only a fraction of at-risk patients go on to develop the syndrome (18), suggesting that host predisposition may be a key determinant for the development of the disease. Whereas ongoing investigations have identified both clinical and genetic risk factors for the development of ARDS (18, 32), little is known about epigenetic phenomena, including microRNAs (miRNAs), that may impact gene expression in the lung during the development of ARDS.

miRNAs are small noncoding segments of RNA that regulate gene expression by binding to complementary sequences on messenger RNA (mRNA) and preventing their translation into protein (6). They can exert pleiotropic downstream effects on cellular function, since individual miRNAs can potentially inhibit the expression of dozens of different genes (29). miRNAs are known to circulate in the bloodstream either in extracellular vesicles (e.g., exosomes; see Ref. 45) or chaperoned by proteins (4, 46) and can be internalized by recipient cells via clathrin-dependent and -independent mechanisms (31) where they can alter gene expression and cellular function (22, 33, 53). Through continuous contact with the bloodstream, the endothelium is well positioned to encounter and internalize circulating extracellular miRNAs, which have been shown to play a key role in modulating endothelial permeability (21, 22, 53). Thus, extracellular miRNAs could represent a critical epigenetic contributor to the endothelial activation and dysfunction that occurs in ARDS.

We hypothesized that circulating miRNA expression patterns differ between critically ill patients with and without ARDS and that differentially expressed miRNAs may regulate the expression of genes relevant to the disease. Therefore, we set out to compare the expression of circulating miRNAs between at-risk septic patients who do and do not develop ARDS. Furthermore, using both in silico and in vitro analyses, we examined the effects of differentially expressed miRNAs on endothelial cell gene expression and function. Our results suggest a possible role for miR-887-3p in the endothelial activation and dysfunction associated with ARDS and a potentially new therapeutic avenue for ARDS prevention and treatment.

METHODS

Subject recruitment and sample collection.

We screened all new intensive care unit (ICU) admissions at a single tertiary-care academic hospital from July 2013 through December 2016 for the presence of severe sepsis as defined by the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine consensus statement (12). Criteria for inclusion in this study included: age ≥18 yr and admission to the ICU with severe sepsis within the previous 24 h. Patients were excluded from enrollment if: 1) informed consent could not be obtained, 2) their goals of care had transitioned to comfort measures only, 3) they had been treated with an antibiotic for an active infection (prophylactic use accepted) as an outpatient within the last 30 days, or 4) they had been transferred from another hospital and had spent a total of more than 24 h in an ICU before the time of screening. Written informed consent for study participation was obtained from all subjects or their legally authorized representatives as well as from healthy control subjects, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Blood was drawn from each subject by venipuncture or from indwelling intravascular catheters within the first 24 h of their admission to the ICU. Plasma was immediately extracted from each sample and stored as previously described (20). Clinical and demographic information and clinical outcomes were collected from the electronic medical record. Furthermore, each subject was reviewed by the investigators to assess for the development of ARDS at any time during their hospitalization using the Berlin definition (34a).

Plasma miRNA analysis.

Six subjects with ARDS and six subjects without were randomly selected for microarray screening. Plasma samples (250 μL) from each subject were delivered to Exiqon (Vedbaek, Denmark) where RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed into cDNA, which was analyzed using their proprietary miRCURY LNA Universal RT microRNA PCR array. The NormFinder algorithm was applied and suggested that the mean Cq of all the assays detected in each sample was the most stable method for gene expression normalization (3, 35, 38, 42). Normalized expression values were compared between the two groups using the statistical analysis described below, and differentially expressed miRNAs were identified.

Plasma samples from separate subjects with severe sepsis who did (n = 19) and did not (n = 128) develop ARDS were used as an independent validation cohort using qPCR as previously described (20). Total RNA was extracted from plasma using miRNeasy Serum/Plasma kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For miRNA expression, the RNA was reverse transcribed using a QIAGEN miRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). An identical amount of Caenorhabditis elegans miR-39 was spiked into each sample to allow for normalization of Cq values. Normalized expression levels of each of the differentially expressed miRNAs identified in the initial microarray analysis were compared between groups in the validation cohort.

Cell transfection and RNA sequencing.

Identical numbers of pooled human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMECs; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were cultured in Endothelial Basal Media-2 supplemented with endothelial cell basal medium (EBM-2) SingleQuots (Lonza) at 37°C until 80–90% confluence. Cells were then serum starved overnight and transfected, in triplicate, with an miR-887-3p mimic (5′-GUGAACGGGCGCCAUCCCGAGG; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or an allstars negative control siRNA (Qiagen) using the manufacturer’s protocol for the HiPerFect reagent (Qiagen). Later (48 h), RNA was extracted using the RNeasy plus mini kit (Qiagen) from each replicate following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA integrity and quantity were measured with NanoDrop One (Themo Fisher). RNA (2 µg) from each sample was provided to the MUSC genomics core for RNA sequencing. Paired end sequencing was performed on a HiSeq2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Alignment and annotation were performed using the Tuxedo Suite as previously described (26, 43) while fold-change estimation was performed with the DESeq2 Bioconductor library to identify genes that were differentially expressed after transfection with miR-887-3p (1, 2). Differential expression was defined as having at least a twofold increase or decrease in expression with a P value <0.05 after adjustment for multiple comparisons with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Sequencing data have been submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE146063).

Bioinformatic analysis.

Differentially expressed genes from miR-887-3p transfection experiments were input into the iPathway Guide (Advaita, Plymouth, MI) to examine which cellular pathways were most likely to be impacted by the presence of miR-887-3p compared with a scrambled control siRNA. The software estimated the impact on pathways by accounting for the number of genes in each pathway that were differentially expressed in the presence of miR-887-3p (overrepresentation) and by the magnitude of their expression changes, the locations of the altered genes in the pathway, and the number of interactions that altered genes have within a given pathway (accumulated perturbation; see Ref. 14). The probabilities of the overrepresentation and accumulated perturbation of each pathway were combined into a final P value using Fisher’s method and then corrected for multiple comparisons using a false discovery rate (FDR; see Refs. 10 and 11). To validate the pathways identified by the iPathway platform, the differentially expressed gene set was also input into ToppFun (41). Genes of potential relevance to endothelial activation and dysfunction were subsequently validated using real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on cell lysates 48 h after an independent transfection experiment as described below.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from HPMECs after transfection as described above. cDNA was synthesized using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed using the Prism 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using a SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) with a reaction volume of 25 µl. Data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt value calculation with GAPDH for normalization.

Cytokine and chemokine analysis.

HPMECs were transfected with the miR-887-3p mimic or the allstars negative control siRNA in triplicate as described above. After 48 h, medium was collected from each replicate and frozen. Frozen medium was delivered to Eve Technologies (Calgary, Alberta, Canada) for multiplexed cytokine and chemokine measurement.

Transendothelial neutrophil migration assay.

The transendothelial neutrophil migration assay was performed as previously described (49). Briefly, HPMECs (2 × 104 cells in 200 μL EBM-2 medium supplemented with a Bullet kit) were cultured on fibronectin (R&D Systems)-coated Transwell inserts (6.5 mm diameter, 3 µm pore size) and grown for 7 days until confluent. Cells were then transfected with control mimic or 887-3p mimic for 48 h using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Inserts were then washed with PBS two times and transferred to a fresh 24-well plate. A neutrophil suspension (2 × 105 neutrophils/insert) isolated that day from human healthy control blood was added in the upper chamber while the lower chamber was filled with 500 μl EBM-2 medium containing 1 μM formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP, Sigma). The plate was incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Thereafter, migrated neutrophils from the bottom of the well were counted by a Countess II Automated Cell Counter (Life Technologies).

Statistical analysis.

Plasma miRNA expression levels were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. As appropriate, an unpaired t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare expression levels of each detectable miRNA between subjects with ARDS versus subjects without ARDS. Multiple-comparisons testing was performed using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. An unpaired t test was used to compare gene expression during RT-PCR analysis, protein expression during cytokine multiplex analysis, and neutrophil migration. P values <0.05 were considered significant for all analyses. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons during analysis in the validation cohort.

RESULTS

During the study enrollment period, a total of 159 patients were admitted to an ICU with severe sepsis who met all inclusion and exclusion criteria. Their baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. Pneumonia (33%) was the most common cause of sepsis, and gram-negative bacteria (34%) were the most commonly identified pathogens. Over one-quarter of all subjects required mechanical ventilation, and 16% died during their hospitalization. Twenty-five (16%) subjects developed ARDS as a complication of their sepsis. Of these, 21 subjects met diagnostic criteria for ARDS at the time of enrollment and blood sample collection while four subjects developed ARDS within 48 h of enrollment. The baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of subjects with and without ARDS from both the identification and validation cohorts are similarly presented (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of enrolled study subjects

| Identification Cohort |

Validation Cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total Population (n = 159) | With ARDS (n = 6) | Without ARDS (n = 6) | With ARDS (n = 19) | Without ARDS (n = 128) |

| Age, yr ± SD | 58.1 ± 17.0 | 55 ± 18.7 | 55 ± 16.9 | 60.4 ± 15.6 | 57.6 ± 16.9 |

| Male sex (%) | 90 (56) | 4 (67) | 3 (50) | 12 (60) | 68 (52) |

| White race (%) | 102 (63) | 4 (67) | 3 (50) | 15 (75) | 72 (55) |

| Source of infection (%) | |||||

| Pneumonia | 53 (33) | 5 (83) | 3 (50) | 11 (55) | 32 (25) |

| Urinary tract infection | 34 (21) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 4 (20) | 27 (21) |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 32 (20) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 25 (19) |

| Bloodstream infection | 19 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 16 (12) |

| Other | 25 (15) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (5) | 19 (15) |

| Organism (%) | |||||

| Gram-negative bacteria | 56 (35) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 12 (60) | 36 (28) |

| Gram-positive bacteria | 38 (23) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 31 (24) |

| Other/unknown | 69 (43) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 4 (20) | 54 (42) |

| Mechanical ventilation (%) | 55 (34) | 6 (100) | 1 (17) | 20 (100) | 27 (21) |

| Median ICU LOS, days (IQR) | 3 (3.5) | 12 (35) | 2 (5) | 6 (14) | 2 (4) |

| Death (%) | 26 (16) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 10 (50) | 12 (9) |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; IQR, interquartile range.

Differentially expressed plasma miRNAs.

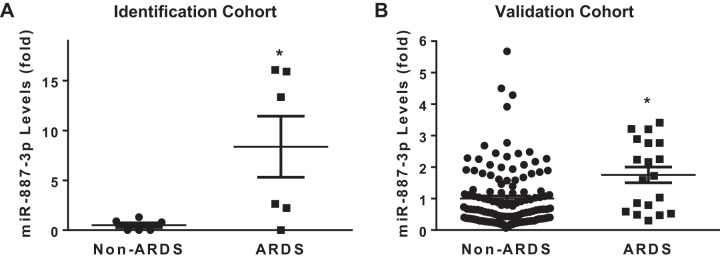

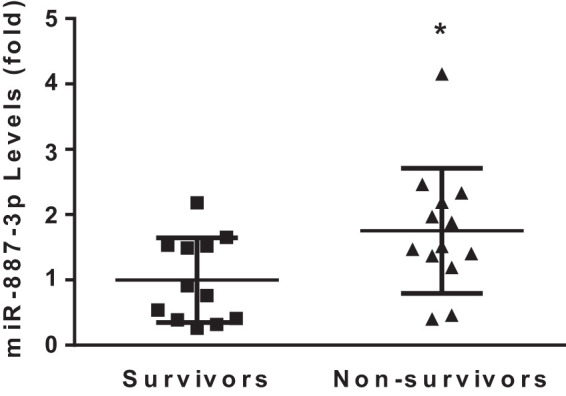

Plasma samples from each subject in the identification cohort were analyzed for circulating miRNA levels and compared between the ARDS (n = 6) and no ARDS (n = 6) groups. Of the 752 miRNAs assayed by the Exiqon miRCURY LNA array, an average of 320 were detected in each sample and 170 were detected in all the samples with a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk, P = 0.4). Of the miRNAs common to all samples, 11 were differentially expressed between the ARDS and no ARDS groups (Table 2). The expression levels of these 11 miRNAs were individually compared between subjects with (n = 19) and without ARDS (n = 128) from a separate validation cohort using quantitative PCR. miRNA 887-3p plasma levels were significantly elevated in subjects who developed ARDS compared with those who did not in both the identification (8.4-fold increase, P < 0.05) and validation (1.8-fold increase, adjusted P < 0.05) cohorts (Fig. 1). Among the 25 subjects with ARDS from both cohorts, those who died during their hospitalization (n = 13, 52%) had significantly higher levels of circulating miR-887-3p (1.8-fold increase, P < 0.05) compared with those who survived (n = 12, Fig. 2). There were no differences in miR-887-3p levels among subjects with ARDS who were (n = 9) and were not (n = 10) receiving mechanical ventilation at the time of sample collection (Supplemental Fig. S1A; see https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3695718) nor among subjects without ARDS who were (n = 13) and were not (n = 9) receiving mechanical ventilation at the time of sample collection (Supplemental Fig. S1B). Furthermore, there was no difference in miR-887-3p levels between races among patients who did or did not develop ARDS (data not shown).

Table 2.

Differentially expressed miRNAs in subjects with ARDS compared with subjects without ARDS in the identification cohort

| miRNA | Fold Change | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| miR-1972 | 14 | 0.007 |

| miR-887-3p | 7.4 | 0.009 |

| miR-15a-3p | −1.9 | 0.01 |

| miR-23b-5p | 2.4 | 0.01 |

| miR-551a | 2.6 | 0.013 |

| miR-24–1-5p | −2.7 | 0.016 |

| miR-148b-3p | −1.4 | 0.023 |

| miR-1468-5p | −2.7 | 0.024 |

| miR-188-5p | 2.4 | 0.031 |

| miR-582-5p | 4.5 | 0.032 |

| miR-378a-5p | 2.2 | 0.049 |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Fig. 1.

Plasma levels of miR-887-3p were elevated in subjects with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) compared with those without ARDS in both the identification (A, n = 6 subjects in each group) and validation (B, n = 128 subjects without ARDS and n = 19 with ARDS) cohorts. Standard deviation shown. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

In the subjects with acute respiratory distress syndrome, nonsurvivors had significantly higher plasma levels of miR-887-3p than survivors (n = 12 survivors, n = 13 nonsurvivors). Standard deviation shown. *P < 0.05.

Endothelial production of miR-887-3p and its impact on endothelial gene expression.

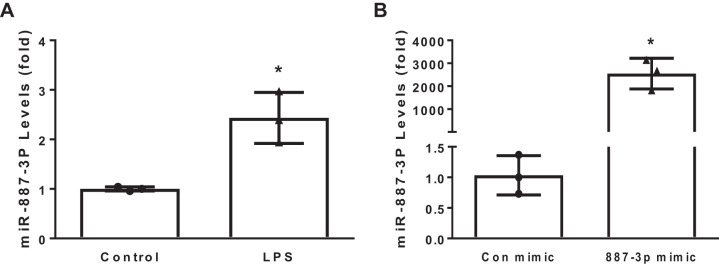

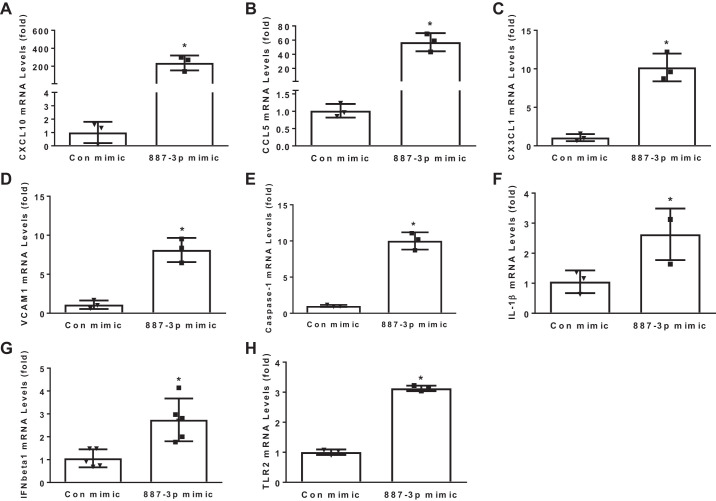

To investigate whether the endothelium may be a source of miR-887-3p in sepsis, HPMECs were treated with 500 ng/mL LPS for 24 h, and cellular levels were examined by PCR. HPMECs express miR-887-3p under baseline conditions; however, exposure to LPS increased expression 2.4-fold (P < 0.05, Fig. 3A). To better understand both the direct and indirect impacts that both endogenous and circulating miR-887-3p would have on endothelial cell gene expression, HPMECs were transfected with synthetic miR-887-3p and a scrambled siRNA control, and RNAseq was performed on extracted cellular RNA. Transfection with synthetic miR-887-3p successfully increased its cellular expression (Fig. 3B). Using a fold change cutoff of 2 and a P value <0.05 after adjustment for multiple comparisons as the threshold for significance, 929 genes were differentially expressed in the presence of increased miR-887-3p, including several with known relevance to ARDS (Table 3), which were confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 4). In silico analysis of the gene expression data predicted cellular pathways and functions that miR-887-3p is likely to modulate. Among the 10 most impacted pathways are cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, influenza A response, cell adhesion molecules, the NF-κB signaling pathway, and antigen processing and presentation. All but two of the most impacted pathways were validated by a second in silico platform (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

A: stimulation of human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells with 500 ng/mL for 24 h augments expression of miR-887-3p. B: transfection with a synthetic miR-887-3p mimic successfully increases its expression levels. Each plot represents 3 experiments. Standard deviation shown. Con, control. *P < 0.05.

Table 3.

HPMEC genes regulated by miR-887-3p with known relevance to ARDS

| Category | Gene | Fold Change | Adjusted P Value | Relevant Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocyte trafficking | CXCL10 | 14.3 | <1 × 10−306 | CXCL10-CXCR3 interaction enhances neutrophil recruitment and lung injury (24) |

| CCL5 | 9.6 | <1 × 10−306 | CCL5 regulates neutrophil migration in experimental acute lung injury (37) | |

| CX3CL1 | 9.5 | 2.49 × 10−284 | Plasma CX3CL1 levels correlate with organ failure and mortality in sepsis (23) | |

| VCAM1 | 5.5 | <1 × 10−306 | Endothelial VCAM1 is elevated in ARDS and facilitates leukocyte trafficking (5) | |

| Endothelial activation/integrity | CASP1 | 5.1 | <1 × 10−306 | Inflammasome activation associated with human ARDS and worsening experimental acute lung injury (13) |

| IL1B | 5.7 | <1 × 10−306 | Inflammasome activation associated with human ARDS and worsening experimental acute lung injury (13) | |

| IFNB1 | 9.8 | 1.1 × 10−89 | Interferon-β1 associated with endothelial permeability and mortality in ARDS (9, 27) | |

| TLR2 | 6.3 | <1 × 10−306 | Toll-like receptor 2 stimulation enhances endothelial cell permeability (25) |

HPMEC, human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CXCL10, C-X-C motif chemokine 10; CCL5, C-C motif chemokine ligand 5; CX3CL1, C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1; VCAM1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; CASP1, caspase 1; IL1B, interleukin-1β; IFNB1, interferon-β1; TLR2, Toll-like receptor 2.

Fig. 4.

PCR validation of human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell genes differentially expressed after miR-887-3p transfection. CXCL10, C-X-C motif chemokine 10; CCL5, C-C motif chemokine ligand 5; CX3CL1, C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1; VCAM1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; IFNβ1, interferon-β1; TLR2, Toll-like receptor 2; Con, control. Represents 3 experiments. Standard deviation shown. *P < 0.05.

Table 4.

Cellular pathways and functions predicted to be modulated by miR-887-3p

| FDR | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pathways | iPathway | ToppFun |

| Ribosome | 3.0 × 10−10 | 7.0 × 10−28 |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 1.6 × 10−6 | 1.2 × 10−31 |

| Herpes simplex infection | 9.3 × 10−6 | 6.0 × 10−10 |

| Influenza A response | 9.3 × 10−6 | 4.0 × 10−30 |

| Cell adhesion molecules | 1.4 × 10−5 | NL |

| TNF signaling pathway | 2.5 × 10−5 | 1.5 × 10−17 |

| Staphylococcus aureus infection | 2.5 × 10−5 | NL |

| NF-κB signaling | 2.5 × 10−5 | 1.1 × 10−7 |

| Antigen processing and presentation | 2.8 × 10−5 | 3.3 × 10−12 |

FDR, false discovery rate; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NF, nuclear factor; NL, not listed in top 50 pathways.

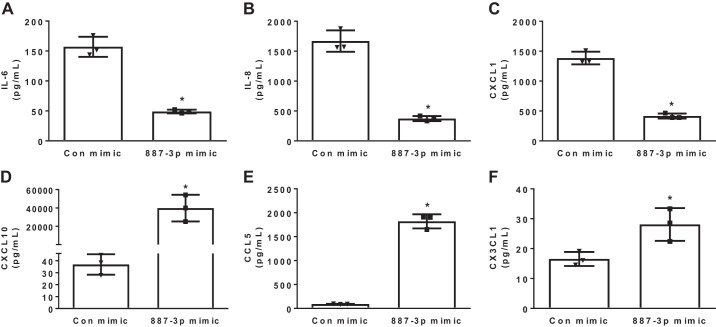

MiR-887-3p regulation of cytokine and chemokine release.

Because miR-887-3p was predicted to regulate the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, the impact of miR-887-3p on endothelial cytokine and chemokine release was examined. HPMECs were transfected with synthetic miR-887-3p, and medium was analyzed by multiplex assay 48 h later. While increased miR-887-3p reduced the endothelial release of several inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and CXCL1, it simultaneously increased the release of chemokines associated with acute lung injury, including CXCL10, CCL5, and CX3CL1 (Fig. 5). Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon-α, interferon-γ, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-1RA, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were not detected by multiplex assay (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Chemokine measurement in human microvascular endothelial cell culture medium 24 h after transfection with miR-887-3p. CXCL1, C-X-C motif chemokine 1; CXCL10, C-X-C motif chemokine 10; CCL5, C-C motif chemokine ligand 5; CX3CL1, C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1; Con, control. Represents 3 experiments. Standard deviation shown. *P < 0.05.

MiR-887-3p enhances neutrophil migration across endothelium.

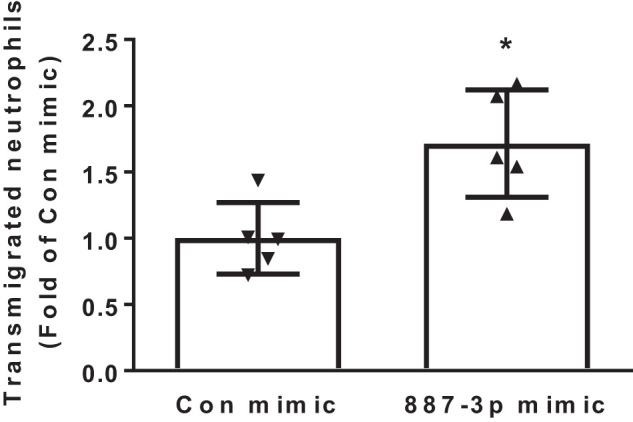

CXCL10, CCL5, and VCAM1 all facilitate neutrophil migration (35, 36, 38); therefore, circulating miR-887-3p may regulate neutrophil trafficking across the endothelium. HPMECs were transfected with synthetic miR-887-3p or a control mimic and grown to confluence on Transwell inserts. Later (48 h), neutrophils were freshly isolated from healthy control blood and added to the upper chamber of each well. Neutrophils migrated across HPMEC monolayers containing miR-887-3p more effectively (1.7-fold, P < 0.05) than across control monolayers (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Transendothelial migration of healthy control neutrophils after transfection with miR-887-3p. Con, control. Results are expressed as fold change of migration across control endothelial cells. Represents 3 experiments. Standard deviation shown. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Our findings have demonstrated that circulating miR-887-3p levels are disproportionately elevated in septic patients who develop ARDS and are highest among patients who died. Moreover, miR-887-3p modulates the endothelial expression of several genes that have previously been associated with the development of ARDS. This diverse regulation of gene expression strategically positions miR-887-3p as a critically important governor of a number of cellular pathways involved in inflammation and the cellular response to infection. As such, miR-887-3p alters endothelial cell function in several important ways, including increasing cytokine and chemokine release and enhancing transendothelial migration by neutrophils. In aggregate, these findings suggest a potentially important role of miR-887-3p in the pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction in ARDS.

There has been considerable focus on the association between miRNAs and sepsis and ARDS (30, 34, 36, 40, 47, 48, 50). Several studies have reported links between circulating miRNA expression and these syndromes although most have demonstrated only associations and have not examined the potential mechanistic roles of miRNAs. Furthermore, many studies have had limited ability to determine the specificity of miRNA expression to these syndromes because of the use of healthy individuals as controls rather than appropriate acutely ill controls. More recently, however, investigators have begun to explore the mechanistic role of miRNAs in acute lung injury. Sun et al. observed that circulating miR-181b levels were reduced in human sepsis and that the miRNA regulated endothelial NF-κB signaling while attenuating experimental acute lung injury (40). Another recent pivotal study demonstrated that polymorphonuclear neutrophils can transfer miR-223 to alveolar epithelial cells, resulting in attenuation of acute lung injury (34). Furthermore, our recent work has shown that exogenously administered endothelial progenitor cells can reduce vascular leak, lung injury, and mortality in experimental sepsis through the delivery of exosomal miR-126 (15, 54). These studies demonstrate that cellular cross talk via miRNAs is a critically important process in acute lung injury with the potential to impact both the development and severity of the syndrome.

The data presented here are novel, since they represent the first description, to our knowledge, of an association between miR-887-3p and ARDS. MiR-887-3p is primarily expressed in endothelial cells and cells of the central nervous system, including neural stem cells, meningeal cells, and astrocytes (44). To date, little is known about its role in human disease. Two groups of investigators recently identified that a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the oncogene murine double minute 4 (MDM4) alters one of its 3′-untranslated region binding sites and renders it susceptible to translational inhibition by miR-887-3p. Accordingly, this oncogene SNP has been associated with improved survival in small cell and nonsmall cell lung cancer as well as prostate cancer (19, 39, 52). MiR-887 has also been identified as upregulated in glioblastoma cells although its significance in this disease is unknown (16). Lai et al. (28) observed that miR-887 levels were decreased in T lymphocytes collected from patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with healthy controls, whereas Beer et al. (7) demonstrated that ionizing radiation upregulates miR-887 expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. To our knowledge, however, miR-887-3p has not been previously associated with sepsis, ARDS, or neutrophil migration (44).

Intriguingly, miR-887-3p levels are not only disproportionately elevated in patients who develop ARDS, but it also increases the endothelial expression of genes associated with ARDS, including VCAM1, CXCL10, CCL5, and CXC3L1 (5, 9, 13, 23–25, 27, 37) and enhances cytokine release, which may potentially explain the observed increase in leukocyte trafficking. Thus, it is possible that miR-887-3p contributes to the pathogenesis of the endothelial dysfunction of ARDS if taken up by the endothelium. However, it did not affect the expression of several genes associated with ARDS (e.g., IL-10, interferon-α and -γ, IL-18, and VEGF). This observation highlights the complexity of the syndrome and suggests that miR-887-3p is likely only one potential regulator of its endothelial dysfunction. Furthermore, these data also demonstrate the underrecognized complexity of downstream gene regulation by miRNAs. Prior investigations on miRNAs in ARDS have largely focused on the potential effect of a miRNA on a single target (30, 32), whereas our data suggest that a single miRNA can have a widespread effect on gene expression. Interestingly, approximately two-thirds of the differentially expressed genes that we identified in response to miR-887-3p transfection were upregulated, and only two differentially expressed genes are predicted to be direct binding targets of the miRNA (TMEM139 and NT5C3) (43). We hypothesize that direct targets of miR-887-3p may function as inhibitors of many of the upregulated genes observed in this study; thus, miR-887-3p disinhibits these downstream genes. These observations suggest that the direct inhibiting effects of miRNAs may result in amplified and diverse downstream effects that should be considered when analyzing the impact of miRNAs on disease pathogenesis and treatment. Further work is needed to dissect which direct targets of miR-887-3p are primarily responsible for the upregulation of the ARDS-relevant genes identified in these data.

Additional investigation is required to better understand the potential role of miR-887-3p in sepsis-related ARDS. Our data suggest that miR-887-3p leads to increased cytokine production and leukocyte trafficking, which may lead to dysregulated inflammation and enhanced lung injury. Alternatively, it is feasible that these downstream effects represent compensatory responses designed to facilitate the clearance of infection and, ultimately, the resolution of the sepsis syndrome. Thus, future studies aimed at examining the impact of miR-887-3p overexpression on sepsis and ALI outcomes are warranted and could clarify the potential role of miR-887-3p in these conditions. Regardless of whether miR-887-3p is helpful or harmful, its circulating levels may have utility as both a prognostic and diagnostic biomarker. Ongoing investigation using appropriately powered patient cohorts will clarify both its association with clinical outcomes and the development of ARDS.

This study has limitations. First, the initial discovery cohort was small (n = 6 in each group), which may have introduced both type I and type II error. However, validation that miR-887-3p was differentially expressed between septic patients with and without ARDS in an independent cohort mitigates the likelihood that this observation was erroneous. Second, although circulating miR-887-3p was observed in both an identification and validation cohort and was shown to affect relevant endothelial cell gene expression and function, we cannot yet determine if the miRNA is causal or merely associated with ARDS. The absence of a rodent homolog to miR-887-3p limited our ability to establish causality in murine sepsis models and will likely necessitate further examination in large animal models of sepsis. Third, while we demonstrated that microvascular endothelial cells produce miR-887-3p and that production is augmented by LPS, we cannot rule out that circulating copies of the miRNA may also originate from alternative cells. Although existing data suggest that miR-887-3p is predominantly produced only in the endothelium and cells of the central nervous system (40), further knowledge of its sources will be critical to inform future work focused on manipulating its expression and activity. Finally, given the pleiotropic nature of miRNAs, it is likely that manipulation of miR-887-3p as a therapeutic approach would have off-target effects that could be either beneficial or detrimental. This potential challenge is highlighted by our data demonstrating that miRNAs can indirectly alter the expression of many downstream genes and is relevant to any silencing RNA-based therapeutic approaches. In silico modeling combined with cellular biology and safety and toxicity data will provide further insight into the therapeutic potential of miR-887-3p targeting.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that circulating levels of miR-887-3p are elevated in septic patients who develop ARDS compared with those who do not. This miRNA is produced by microvascular endothelial cells, and its presence results in downstream upregulation of several genes associated with ARDS. These changes in gene expression impact cellular pathways relevant to the response to infection and lead to increases in cytokine and chemokine release as well as leukocyte trafficking through the endothelium. miR-887-3p may be a key regulator of endothelial activation in sepsis and is a potential target for new therapeutic development.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant K23 HL135263 (A.J.G.), NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grants R01 GM113995 (H.F.) and R01 GM130653 (H.F.), and NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1 TR001450 (P.V.H.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.J.G., P.V.H., J.A.C., and H.F. conceived and designed research; A.J.G., P.L., A.S.S., and H.F. performed experiments; A.J.G., P.L., P.V.H., J.A.C., A.S.S., and H.F. analyzed data; A.J.G., P.L., P.V.H., J.A.C., A.S.S., and H.F. interpreted results of experiments; A.J.G. prepared figures; A.J.G. drafted manuscript; A.J.G., P.L., P.V.H., and H.F. edited and revised manuscript; A.J.G., P.L., P.V.H., J.A.C., A.S.S., and H.F. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11: R106, 2010. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders S, McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Okoniewski M, Smyth GK, Huber W, Robinson MD. Count-based differential expression analysis of RNA sequencing data using R and Bioconductor. Nat Protoc 8: 1765–1786, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Ørntoft TF. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res 64: 5245–5250, 2004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, Mitchell PS, Bennett CF, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Stirewalt DL, Tait JF, Tewari M. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 5003–5008, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attia EF, Jolley SE, Crothers K, Schnapp LM, Liles WC. Soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1) is elevated in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. PLoS One 11: e0149687, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297, 2004. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beer L, Seemann R, Ristl R, Ellinger A, Kasiri MM, Mitterbauer A, Zimmermann M, Gabriel C, Gyöngyösi M, Klepetko W, Mildner M, Ankersmit HJ. High dose ionizing radiation regulates micro RNA and gene expression changes in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. BMC Genomics 15: 814, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, Ranieri M, Rubenfeld G, Thompson BT, Wrigge H, Slutsky AS, Pesenti A, Investigators LS, Group ET; LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group . Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA 315: 788–800, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellingan G, Maksimow M, Howell DC, Stotz M, Beale R, Beatty M, Walsh T, Binning A, Davidson A, Kuper M, Shah S, Cooper J, Waris M, Yegutkin GG, Jalkanen J, Salmi M, Piippo I, Jalkanen M, Montgomery H, Jalkanen S. The effect of intravenous interferon-beta-1a (FP-1201) on lung CD73 expression and on acute respiratory distress syndrome mortality: an open-label study. Lancet Respir Med 2: 98–107, 2014. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57: 289–300, 1995. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann Stat 29: 1165–1188, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ; The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine . Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Chest 101: 1644–1655, 1992. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolinay T, Kim YS, Howrylak J, Hunninghake GM, An CH, Fredenburgh L, Massaro AF, Rogers A, Gazourian L, Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Landazury R, Eppanapally S, Christie JD, Meyer NJ, Ware LB, Christiani DC, Ryter SW, Baron RM, Choi AM. Inflammasome-regulated cytokines are critical mediators of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 1225–1234, 2012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0003OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Draghici S, Khatri P, Tarca AL, Amin K, Done A, Voichita C, Georgescu C, Romero R. A systems biology approach for pathway level analysis. Genome Res 17: 1537–1545, 2007. doi: 10.1101/gr.6202607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan H, Goodwin AJ, Chang E, Zingarelli B, Borg K, Guan S, Halushka PV, Cook JA. Endothelial progenitor cells and a stromal cell-derived factor-1α analogue synergistically improve survival in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189: 1509–1519, 2014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2163OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Floyd DH, Zhang Y, Dey BK, Kefas B, Breit H, Marks K, Dutta A, Herold-Mende C, Synowitz M, Glass R, Abounader R, Purow BW. Novel anti-apoptotic microRNAs 582-5p and 363 promote human glioblastoma stem cell survival via direct inhibition of caspase 3, caspase 9, and Bim. PLoS One 9: e96239, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gajic O, Dabbagh O, Park PK, Adesanya A, Chang SY, Hou P, Anderson H III, Hoth JJ, Mikkelsen ME, Gentile NT, Gong MN, Talmor D, Bajwa E, Watkins TR, Festic E, Yilmaz M, Iscimen R, Kaufman DA, Esper AM, Sadikot R, Douglas I, Sevransky J, Malinchoc M, Illness USC; U.S. Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group: Lung Injury Prevention Study Investigators (USCIITG-LIPS) . Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury: evaluation of lung injury prediction score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 462–470, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0549OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao F, Xiong X, Pan W, Yang X, Zhou C, Yuan Q, Zhou L, Yang M. A regulatory mdm4 genetic variant locating in the binding sequence of multiple microRNAs contributes to susceptibility of small cell lung cancer. PLoS One 10: e0135647, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodwin AJ, Guo C, Cook JA, Wolf B, Halushka PV, Fan H. Plasma levels of microRNA are altered with the development of shock in human sepsis: an observational study. Crit Care 19: 440, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo C, Goodwin A, Buie JNJ, Cook J, Halushka P, Argraves K, Zingarelli B, Zhang X, Wang L, Fan H. A stromal cell-derived factor 1α analogue improves endothelial cell function in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Mol Med 22: 115–123, 2016. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2015.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hergenreider E, Heydt S, Tréguer K, Boettger T, Horrevoets AJ, Zeiher AM, Scheffer MP, Frangakis AS, Yin X, Mayr M, Braun T, Urbich C, Boon RA, Dimmeler S. Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nat Cell Biol 14: 249–256, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ncb2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoogendijk AJ, Wiewel MA, van Vught LA, Scicluna BP, Belkasim-Bohoudi H, Horn J, Zwinderman AH, Klein Klouwenberg PM, Cremer OL, Bonten MJ, Schultz MJ, van der Poll T; MARS consortium . Plasma fractalkine is a sustained marker of disease severity and outcome in sepsis patients. Crit Care 19: 412, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichikawa A, Kuba K, Morita M, Chida S, Tezuka H, Hara H, Sasaki T, Ohteki T, Ranieri VM, dos Santos CC, Kawaoka Y, Akira S, Luster AD, Lu B, Penninger JM, Uhlig S, Slutsky AS, Imai Y. CXCL10-CXCR3 enhances the development of neutrophil-mediated fulminant lung injury of viral and nonviral origin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 65–77, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0508OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khakpour S, Wilhelmsen K, Hellman J. Vascular endothelial cell Toll-like receptor pathways in sepsis. Innate Immun 21: 827–846, 2015. doi: 10.1177/1753425915606525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 14: R36, 2013. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiss J, Yegutkin GG, Koskinen K, Savunen T, Jalkanen S, Salmi M. IFN-beta protects from vascular leakage via up-regulation of CD73. Eur J Immunol 37: 3334–3338, 2007. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai NS, Yu HC, Tung CH, Huang KY, Huang HB, Lu MC. The role of aberrant expression of T cell miRNAs affected by TNF-α in the immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 19: 261, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1465-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120: 15–20, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ling Y, Li ZZ, Zhang JF, Zheng XW, Lei ZQ, Chen RY, Feng JH. MicroRNA-494 inhibition alleviates acute lung injury through Nrf2 signaling pathway via NQO1 in sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Life Sci 210: 1–8, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Théry C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol 21: 9–17, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer NJ. Future clinical applications of genomics for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 1: 793–803, 2013. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mittelbrunn M, Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Villarroya-Beltri C, González S, Sánchez-Cabo F, González MA, Bernad A, Sánchez-Madrid F. Unidirectional transfer of microRNA-loaded exosomes from T cells to antigen-presenting cells. Nat Commun 2: 282, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neudecker V, Brodsky KS, Clambey ET, Schmidt EP, Packard TA, Davenport B, Standiford TJ, Weng T, Fletcher AA, Barthel L, Masterson JC, Furuta GT, Cai C, Blackburn MR, Ginde AA, Graner MW, Janssen WJ, Zemans RL, Evans CM, Burnham EL, Homann D, Moss M, Kreth S, Zacharowski K, Henson PM, Eltzschig HK. Neutrophil transfer of miR-223 to lung epithelial cells dampens acute lung injury in mice. Sci Transl Med 9: eaah5360, 2017. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aah5360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34a.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS, Slutsky AS; ARDS Definition Task Force . Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 307: 2526–2533, 2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratert N, Meyer HA, Jung M, Mollenkopf HJ, Wagner I, Miller K, Kilic E, Erbersdobler A, Weikert S, Jung K. Reference miRNAs for miRNAome analysis of urothelial carcinomas. PLoS One 7: e39309, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roderburg C, Luedde M, Vargas Cardenas D, Vucur M, Scholten D, Frey N, Koch A, Trautwein C, Tacke F, Luedde T. Circulating microRNA-150 serum levels predict survival in patients with critical illness and sepsis. PLoS One 8: e54612, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russkamp NF, Ruemmler R, Roewe J, Moore BB, Ward PA, Bosmann M. Experimental design of complement component 5a-induced acute lung injury (C5a-ALI): a role of CC-chemokine receptor type 5 during immune activation by anaphylatoxin. FASEB J 29: 3762–3772, 2015. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-271635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarzenbach H, da Silva AM, Calin G, Pantel K. Data normalization strategies for microRNA quantification. Clin Chem 61: 1333–1342, 2015. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.239459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stegeman S, Moya L, Selth LA, Spurdle AB, Clements JA, Batra J. A genetic variant of MDM4 influences regulation by multiple microRNAs in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 22: 265–276, 2015. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun X, Icli B, Wara AK, Belkin N, He S, Kobzik L, Hunninghake GM, Vera MP, Blackwell TS, Baron RM, Feinberg MW, Feinberg MW; MICU Registry . MicroRNA-181b regulates NF-κB-mediated vascular inflammation. J Clin Invest 122: 1973–1990, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI61495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ToppGene Suite (Online). https://toppgene.cchmc.org/ [February 2020].

- 42.Torres A, Torres K, Wdowiak P, Paszkowski T, Maciejewski R. Selection and validation of endogenous controls for microRNA expression studies in endometrioid endometrial cancer tissues. Gynecol Oncol 130: 588–594, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 28: 511–515, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.UCSC Genome Browser Gateway (Online). https://genome.ucsc.edu/ [February 2020].

- 45.Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol 9: 654–659, 2007. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol 13: 423–433, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ncb2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, Zhang P, Chen W, Feng D, Jia Y, Xie L. Serum microRNA signatures identified by Solexa sequencing predict sepsis patients’ mortality: a prospective observational study. PLoS One 7: e38885, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang HJ, Zhang PJ, Chen WJ, Feng D, Jia YH, Xie LX. Four serum microRNAs identified as diagnostic biomarkers of sepsis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 73: 850–854, 2012. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825a7560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J, Xu J, Zhao X, Xie W, Wang H, Kong H. Fasudil inhibits neutrophil-endothelial cell interactions by regulating the expressions of GRP78 and BMPR2. Exp Cell Res 365: 97–105, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang JF, Yu ML, Yu G, Bian JJ, Deng XM, Wan XJ, Zhu KM. Serum miR-146a and miR-223 as potential new biomarkers for sepsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 394: 184–188, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342: 1334–1349, 2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang Y, Gao W, Ding X, Xu W, Liu D, Su B, Sun Y. Variations within 3′-UTR of MDM4 gene contribute to clinical outcomes of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients following platinum-based chemotherapy. Oncotarget 8: 16313–16324, 2017. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H, Shagdarsuren E, Gan L, Denecke B, Hristov M, Köppel T, Jahantigh MN, Lutgens E, Wang S, Olson EN, Schober A, Weber C. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal 2: ra81, 2009. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou Y, Li P, Goodwin AJ, Cook JA, Halushka PV, Chang E, Fan H. Exosomes from endothelial progenitor cells improve the outcome of a murine model of sepsis. Mol Ther 26: 1375–1384, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]