Abstract

Background

The current COVID-19 pandemic has challenged the infrastructure of the healthcare systems. To cope with the pandemic, substantial changes were introduced to surgical practice and education all over the world.

Methods

A scoping search in PubMed and Google Scholar was done using the search terms: “Coronavirus,” “COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “nCoV-2019”, and “surgery.” They were either searched individually or in combination. All relevant articles of any study design (published within December 15, 2019, till the mid of June 2020), were included and narratively discussed in this review.

Results

Sixty-six articles were reviewed in this article. Through these articles, we provide guidance and recommendations on the preoperative preparation and safety precautions, intraoperative precautions, postoperative precautions, postoperative complications (related to COVID-19), surgical scheduling, emergency surgeries, elective surgeries, cancer surgery, psychological impact on surgical teams, and surgical training during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemic has affected nearly all aspects of surgical procedures, scheduling, and staffing. Special precautions were taken before, during, or after surgeries. New treatment and teaching modalities emerged in response to the pandemic. Psychological support and training platforms are necessary for the surgical team.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Surgery, Emergency, World health organization, Telemedicine

Highlights

-

•

Strict surgical protective measures should be taken to avoid viral transmission.

-

•

Decision to postpone elective surgeries is a multidisciplinary one.

-

•

Mental and psychological support is essential for surgeons during the pandemic.

-

•

The pandemic profoundly impacts surgical practice and training.

-

•

Guidelines to improve surgical practice during the pandemic are rapidly evolving.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a global pandemic affecting over 3 million people and has vastly impacted healthcare systems worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) officially recognized this public health issue as an international emergency on March 11, 2020 [1]. The surgical field has been influenced as a result of the massive redirection of medical attention and priority towards caring for the COVID-19 infected patients. The economic demands of this global issue are increasing, and they are being exacerbated by the needs of surgical procedures [2]. Also, surgeons are now facing the challenge of maintaining their care and working to reduce the nosocomial spread of the virus.

On March 12, 2020, the United States of America (USA), Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended canceling all the elective surgeries at Santa Clara County, California [3]. Further, many general guidelines were released to set the criteria of case classification in order to define elective surgeries that can be postponed and urgent procedures that need a rapid intervention [4,5]. Surgeons should decide on the indications basing on a case-by-case approach. Moreover, in order to avoid person-to-person contact, experts suggested taking benefit from the recent technologies in making remote consultations, patients’ allocation and triage, educating junior surgeons, and knowledge sharing [6].

The timing of cancer surgery is critical to limit tumor progression, prevent or delay metastases, and improve patient survival. Therefore, cancer surgeries, which might be life-saving, are of particular concern during the current pandemic. The decision on delaying the resection should be discussed by the responsible surgical team that should, in this case, take into consideration the risk of nosocomial contamination with SARS-CoV-2, and the risk of tumor spread and metastasis [7].

This narrative review provides a global view of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the surgical field. We summarized the safety measures required in the different operative and postoperative phases. We also highlighted the impact of COVID-19 on elective and cancer surgery scheduling and the evolvement of the process of taking surgical decisions. Finally, we discussed the impact of the pandemic on the surgical staff mental health and education.

2. Methods

We conducted a scoping review of published literature on the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on surgical practice and training. We also aimed to review the evolvement of the principals of decision-making regarding the possibility of postponing or performing different surgical procedures. The search included all relevant articles from December 2019 till the mid of June 2020.

2.1. Literature search

A computer literature search of PubMed and Google Scholar was done using the following keywords: “Coronavirus”, “COVID-19”, “pandemic”, “surgical”, “surgery”, “elective surgery”, “emergency surgery”, “surgical training”, “surgical preparation”, “surgeons”, and “surgical residents”. They were either used individually or in combination.

2.2. Scope and criteria

We included all relevant articles about the impact of COVID-19 on any of the following surgical domains [1]: preoperative preparation and safety precautions [2], intraoperative precautions [3], postoperative precautions [4], postoperative complications (related to COVID-19) [5], surgical scheduling [6], emergency surgeries [7], elective surgeries [8], cancer surgeries [9], psychological impact on surgical teams, and [10] surgical training. We included published articles that are available in the English language, of any study design as well as the WHO related reports, and the guidelines for surgical practice released by credited institutions or professional associations. Studies were classified according to their scope, their findings, and recommendations. They were tabulated and discussed narratively.

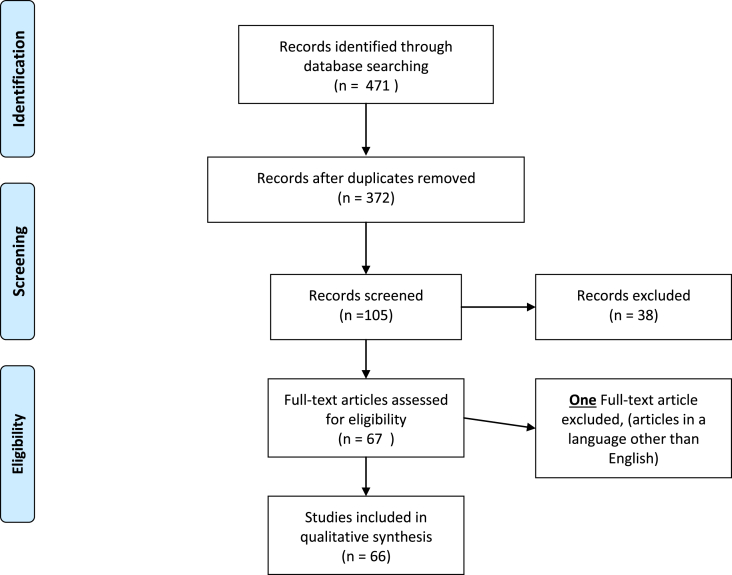

In this review, we followed the checklist of the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA)” [8]. The selection process is explained by the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram explains the selection process

3. Results

The literature search identified 471 articles. Of them, 66 articles and reports were eligible for inclusion in this scoping review (related to surgical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic). The summary of the included articles is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

shows a summary of the articles included in this scoping review

| Scope | Study ID | Place or professional society | Article type or study design | Key points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative preparation & safety precautions | Combira R. et al, 2020 | European Society of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (ESTES) | Guidelines/Recommendations |

|

| Saadi RA et al, 2020 | USA | Guidelines/Recommendations |

|

|

| Givi B et al, 2020 | USA | Review article and Recommendations |

|

|

| Pichi B et al. 2020 | Italy | Guidelines/Recommendations |

|

|

| Forrester JD et al, 2020 | USA | Guidelines/Recommendations |

|

|

| Intraoperative precautions | Ti LK et al, 2020 | Singapore | Letter to the editor |

|

| Postoperative precautions | Tan Z et al, 2020 | Singapore | Recommendation/Guidelines |

|

| Sica GS et al. | Italy | Debate article |

|

|

| Wong J et al, 2020 | Singapore | Review article |

|

|

| Postoperative complications (related to COVID-19) | Aminian A et al, 2020 | Iran | Case series |

|

| Fukuhara S et al, 2020 | China | Retrospective cohort |

|

|

| COVIDSurg Collaborative 2020 | International study | Cohort study |

|

|

| Surgical scheduling | Topf MC et al, 2020 | USA | Recommendations/Guidelines |

|

| COVIDSurg Collaborative 2020 | International study | A global expert-response study |

|

|

| Yu GY 2020 | China | Recommendations/strategies |

|

|

| Stahel PF et al, 2020 | USA | Editorial |

|

|

| American College of Surgeons, American Society of Anesthesiologists, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, and American Hospital Association, 2020 | USA | Joint statement/ strategies |

|

|

| Wiseman SM et al. 2020 | Canada | Commentary |

|

|

| Zarrintan S et al, 2020 | Iran | Correspondence |

|

|

| American college of Surgeons, 202 | USA | Guidelines/ Recommendations |

|

|

| Emergency surgeries | Lisi G et al, 2020 | Italy | Correspondence |

|

| Combira R. et al, 2020 | European Society of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (ESTES) | Recommendations |

|

|

| Patriti A et al, 2020 | Italy | Letter to the editor |

|

|

| Pryor A et al, 2020 | USA | Recommendation |

|

|

| Stahel PF ,2020 | USA | Editorial |

|

|

| Topf MC et al, 2020 | USA |

|

||

| Lisi G et al, 2020 | USA | Guidelines |

|

|

| Elective surgeries | Topf MC et al, 2020 | USA | Recommendations/Guidelines |

|

| Yu GY et al , 2020 | China | Recommendations/strategies |

|

|

| Stahel PF et al, 2020 | USA | Editorial |

|

|

| American College of Surgeons, American Society of Anesthesiologists, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, and American Hospital Association, 2020 | USA | Joint statement/ strategies |

|

|

| Zarrintan S et al,2020 | Iran | Correspondence |

|

|

| American college of Surgeons, 2020 | USA | Guidelines/ Recommendations |

|

|

| Cancer surgery | Gillessen S et al, 2020 | Europe | Editorial |

|

| Liang W et al, 2020 | China | Comment |

|

|

| Mehta V et al, 2020 | USA | Observational study |

|

|

| Kuderer NM et al, 2020 | USA | Cohort study |

|

|

| Di Saverio et al, 2020 | Italy | Guidance |

|

|

| Sharma et al. 2020 | India | Review Article |

|

|

| van Harten MC et al, 2014 | Germany | Retrospective cohort |

|

|

| Samson P et al, 2015 | USA | Retrospective cohort |

|

|

| Grotenhuis BA et al, 2010 | Northlands | Cohort Study |

|

|

| Van Harten MC et al, 2015 | Northlands | Retrospective cohort |

|

|

| Robinson KM et al, 2012 | Denmark | Survey study |

|

|

| Bartlett DL et al, 2020 | USA | Editorial |

|

|

| De Felice F et al, 2020 | Italy | Correspondence |

|

|

| Ueda M et al,2020 | USA | Special feature |

|

|

| Ciavattini A et al, 2020 | Italy | Special article |

|

|

| Stensland KD et al, 2020 | USA | Editorial |

|

|

| Ficarra V et al, 2020 | Italy | Short communication |

|

|

| Campi R et al, 2020 | Italy | Retrospective cohort |

|

|

| Pellino G et al, 2020 | Italy | Viewpoint |

|

|

| Çakmak GK 2020 |

Turkey | Editorial |

|

|

| Sullivan M et al, 2020 | Child cancer organizations: SIOP,SIOP-E,COG,SIOP-PODC,IPSO,PROS, ICPCN, St Jude Global, and the WHO | Special report |

|

|

| Downs et al, 2020 | Australia | Correspondence |

|

|

| The Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, 2020 | USA | Consensus Statement |

|

|

| Fregatti P et al, 2020 | Italy | Observational clinical study |

|

|

| Sud et al, 2020 | United Kingdom/ the data was from Wuhan | Predictive design analysis |

|

|

| Chang et al, 2020 | USA | Prospective and retrospective assessment of cancer surgery cases |

|

|

| Cenzato M et al, 2020 | Italy | Editorial |

|

|

| Fakhry N et al, 2020 | France | Recommendations |

|

|

| Psychological impact on surgical teams | Xu J et al, 2020 | China | Pre-proof |

|

| Neto MLR et al, 2020 | Brazil | Review article |

|

|

| Surgical training | Tomlinson SB et al, 2020 | USA/India | Editorial |

|

| Chick RC et al, 2020 | USA | Perspectives |

|

|

| Kogan M et al, 2020 | USA | Standard Review |

|

|

| Porpiglia F et al, 2020 | Europe | comment |

|

|

| Amparore D et al, 2020 | Italy | Review article |

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Preoperative preparation and safety precautions during COVID-19 pandemic

Many articles in the literature have emphasized on the importance of having a separate operating room (OR) complex designated to serve COVID-19 infected patients going for a surgical procedure [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. These operating theaters should be set at negative pressure interiorly, unlike the standard conventional positive pressure rooms, which aids in preventing the spread of SARS-COV-2 outside the OR. The designated OR complex may be away from the main OR complex in order to limit the occurrence of any cross-contamination among patients. The OR doors should be shut at all times as far as the surgery is taking place, and the number of individuals entering and exiting the OR should be strictly limited [11].

All equipment that will be potentially used for any procedure must be inside the OR prior to the patient's entry [9,11,13]. Spare instruments and devices inside the OR are beneficial in decreasing the likelihood of any staff member moving in or out of the OR [11]. Disposable equipment has been used as an alternative to reusable ones [9].

Regarding the staff attire, appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) was always a standard precaution taken during whenever medical personnel was dealing with a COVID-19 patient. Several papers heavily emphasized this practice [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. The variations in the literature were very minimal, as most of the hospitals already require a disposable cap, gown, gloves, N95 mask, and a face-shield for dealing with the infected patients in intensive care units (ICU) or the preoperative isolation ward. PPE donning was performed at a specially designated area in close vicinity to the OR [13]. An article by Pichi et al. [15] described a “buddy check” where two individuals check each other to ensure both were wearing full PPE. A mandatory PPE donning and doffing training was also mentioned in a study by Forrester et al. [16]. Wong et al. also mentioned an in situ simulation training to test the preparedness of the healthcare staff to manage COVID-19 patients while in full PPE and Powered Air-Purifying Respirator (PAPR) to address any unapparent problem that may arise in a real event later on [13].

The patients should be transferred directly without having to wait in the preoperative holding area [9]. Charting and consent should be done electronically using touch screen devices for easier decontamination and lower risk of infection spread through pens, papers, etc. [13]. Having a separate elevator designated to carrying COVID-19 patients was mentioned as well [9]. Patients should be transferred while wearing a gown, gloves, N95 mask, and eye protection. All additional staff should be out of the OR during intubation, and doors should be closed for 10 min post-intubation [11].

4.2. Intraoperative precautions during COVID-19 pandemic

All staff members in the OR should be wearing full PPE, double gloves, and an extra surgical mask over the N95, followed by Powered Air-Purifying Respirator for maximum protection (PAPR) is recommended [9]. Two studies mentioned a runner being available by phone to serve the OR either by entering directly or by the use of an anteroom. The materials that are being transferred to the OR (e.g., instruments) or out of it (e.g., frozen sections) placed on a trolley in the anteroom for the runner or the staff in the OR to retrieve hence limiting direct contact with each other [9,12]. The most experienced surgeons are advised to perform those surgeries on infected patients to ensure operations done in the timeliest manner and reduce the possibility of intraoperative complications [9]. Electrocautery and laser use should be limited as much as possible in order to reduce the generated fumes. The smoke produced during the usage of electrocautery should be eliminated by special evacuators [9].

4.3. Postoperative precautions during COVID-19 pandemic

Extubation and recovery should be made in the OR, and the route to the ICU or isolation ward should be cleared by security. A minimum of 1 h between cases is advised for thorough decontamination of the operating rooms [12]. The healthcare staff members involved are encouraged to change the scrubs after each case [9] and to shower before resuming normal activities [11]. When possible, Postoperative visits should be replaced with phone calls [13]. In order to reduce the in-hospital stay, enhanced recovery programs have also been applied in many centers. A recent report demonstrated that patients could cope easily with these new protocols since they are aware of the infectious risk [17].

4.4. Postoperative COVID-19 related complications

The literature regarding COVID-19-related postoperative complications is insignificant. Postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), shock, arrhythmias, acute cardiac injury, or even death of COVID-19 patients were recorded in some studies [18,19].

COVID-19-positive patients undergoing surgery may be the subject of major postoperative complications, even if they do not have any symptoms of respiratory infection [18,19]. This is why more precautions are required in performing surgical procedures for COVID-19 patients in order to avoid the severe problems that can, consequently, consume healthcare resources.

The international cohort study by the COVIDSurg Collaborative reported that the 30-day mortality was 23.8% among COVID-19 patients who underwent surgery. The pulmonary complication occurred in more than half of the studied patients (51.2%), among whom the mortality was 38.0%. They observed higher mortality rates among males, patients aged 70 years or more, patients graded by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) from 3 to 5, malignant disease surgeries, emergency surgeries or major surgeries [20]. The results of this COVIDSurg study imply that the threshold for surgery should be higher for COVID-19 patients since they are at greater risk of more complications and mortality.

4.5. Surgical scheduling during the COVID-19 pandemic

It is clear -without any doubt-that emergency and trauma surgical patients should be managed during this pandemic without any delay, yet reconciliation between the interpretation of “elective, non-urgent” and patient's health could be a challenge. For this, we are discussing (I) COVID -19 and elective surgeries and (II) COVID-19 and surgical emergencies.

(I). Elective surgeries during the COVID-Pandemic

In response to the current pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), several official institutions have canceled or postponed elective and non-urgent surgical procedures. This reduction has its advantages as increasing capacity for COVID-19 patients in general wards and intensive care units, reducing the risk of cross-infection between COVID-19 patients and other patients, supporting emergency care, and preserving PPE [21].

A Bayesian β-regression model included 71 countries, estimated the surgical cancellation rates during the 12-week lockdown to be 23⋅4–77⋅1% for cancer surgeries, 71⋅2–87⋅4% for non-cancer surgeries, and 17⋅4–37⋅8% for obstetrics surgeries. The same study expected a median of 45 weeks for the world to recover from this backlog of operations if the baseline surgical rates increased by 20% [22].

Surgeries for benign tumors -confirmed with pathological reports-can be postponed, but the whole surgical team should decide surgeries for malignant tumors. Reconstructive and plastic surgeries could be delayed. Unless life-threatening, most orthopedic, urologic, and neurosurgical operations can also be suspended. Palliative surgical management of gastrointestinal obstructions should not be delayed. Concerning vascular surgery conditions like catheter dialysis placement in renal failure patients, ruptured arterial aneurysms, severe deep venous thromboembolism (DVT) associated with phlegmasia should be managed emergently or urgently; whereas, other conditions like most of the venous and lymphatic procedures, aortoiliac occlusive disease, and peripheral arterial disease could be delayed [7].

It may be essential for each surgical specialty to have clear algorithms and frameworks to guide the surgeon's decision-making for proper surgical care. For example, the Division of Head and Neck Surgery in the Department of Otolaryngology at Stanford University has stratified head and neck cases by urgency into four major categories: urgent-proceed surgically, less urgent – consider postponing >30 days, less urgent – consider postponing 30–90 days, and case-by-case basis [21].

On the other side, the entity of elective surgery delaying could have a more negative impact on the patient's health than mortality and morbidity caused by COVID-19. A publication by the Naval Medical University highlighted the major risks of postponing surgeries for colorectal cancer during the COVID-19 period [23,24].

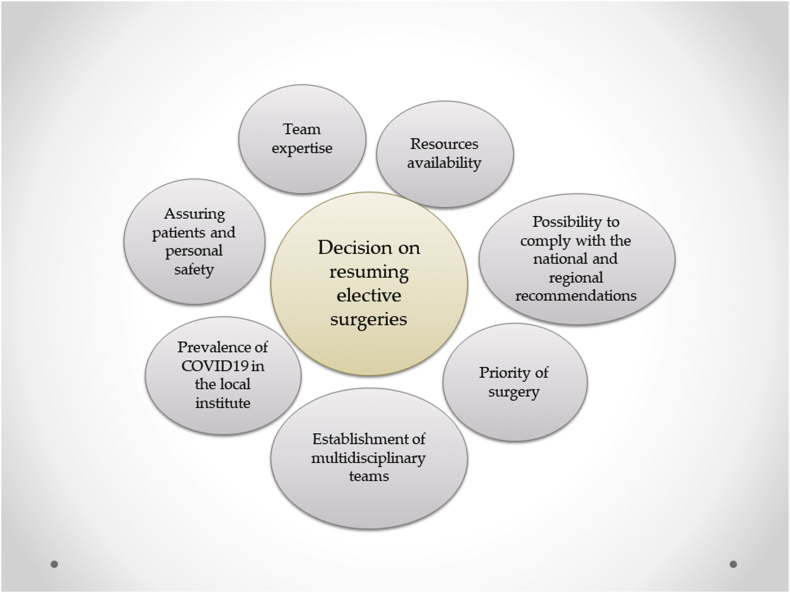

The American College of Surgeons, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the Association of perioperative Registered Nurses, and the American Hospital Association have announced a joint statement (April 17, 2020) to guide the roadmap for resuming elective surgeries after COVID-19 pandemic [25]. Besides, the American College of Surgeons has published guidance for the resumption of elective surgeries (April 17, 2020) [26]. The first decisions on postponing all the elective surgeries have led to the generation of waiting lists that included thousands of patients [27]. Consequently, professionals are now focusing on generating protocols to resume elective procedures. These protocols are taking in consideration all the possible scenarios for each hospital. For instance, some teams have generated specific scores to help in achieving this process. In front of all these evolving recommendations, all the surgical teams are now asked to take many considerations before deciding on the resumption of elective surgeries. These considerations include the personal expertise, the risk of infection to both staff and patients, the national and regional guidelines, and the availability of the resources (Fig. 2) [25,26].

Fig. 2.

General considerations for resuming elective surgeries.

(II). Emergency surgeries during the COVID-19

The definition of emergency surgery has always been a relevant issue even before the era of COVID-19. Despite all the efforts of the global institutions to establish a comprehensive definition, there is always a place for a case-dependent subjective evaluation by surgeons. To overcome this amid the pandemic, several institutions issued recommendations about decision making and definitive criteria to decide the severity of the presented case. Every acute admission must be evaluated by at least two surgeons (consultants, attendants) to assess the risk difference between proceeding and delaying, and to weigh the role of alternative interventions. A summary of some of the most common surgical emergencies was listed in Table 2 [9,21,24,28,29].

Table 2.

List of different types of surgical emergencies.

| Case Example | Urgency | Indication |

|---|---|---|

| Emergent | Less than 1 h | Life-threating emergencies |

| Acute exsanguination/hemorrhagic shock | ||

| Trauma level 1 activations | ||

| Acute vascular injury or occlusion | ||

| Aortic dissection | ||

| Emergency C-section | ||

| Acute compartment syndrome | ||

| Necrotizing fasciitis | ||

| Peritonitis | ||

| Bowel obstruction/perforation | ||

| Urgent | More than 24 h | Appendicitis/cholecystitis |

| Septic arthritis | ||

| Open fractures | ||

| Bleeding pelvic fractures | ||

| Femur shaft fractures & hip fractures | ||

| Acute nerve injuries/spinal cord injuries | ||

| Surgical infections |

As mentioned previously, most of the surgical admissions have been limited to include only urgent and emergent life-threatening conditions. As a result, COVID-19 has resulted in a significant reduction in the number of surgical admissions worldwide [24]. Due to the lack of sufficient evidence regarding the impact of the pandemic on surgical emergency and the lack of clear global definitive criteria for the later in the era of COVID-19, the random cancellation of most surgeries has led to unpleasant consequences [30].

Most of the global and regional institutes started to stress on this issue in their guidelines and recommendations. The European Society of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (ESTES) new recommendations have stated that “care should be taken to limit delay of interventions and to maintain quality of interventions’ [9].

The question has been raised here whether to request COVID-19 testing for emergent surgery cases or not. The general rule is to test all surgery patients upon admission; however, surgeons should not delay the time of initiation waiting for test results. In fact, during this pandemic, all patients should be considered COVID-19 positive, and precautions must be adequately considered in all cases [28,31].

4.6. Cancer surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic

The surgical management of cancer patients during the period of COVID-19 is imposing critical challenges to the medical personnel. On the one hand, the increasing demands of handling the pandemic of coronavirus affect the capacities of managing the surgical plans of patients with malignant diseases [32]. On the other hand, cancer patients are more susceptible to develop severe infections leading to an invasive procedure and poor outcomes [[33], [34], [35]]. Also, cancer surgeries expose the patients to the risks of perioperative complications, which necessitate intensive postoperative care, longer hospitalizations, and increasing the probability of infection [18,36,37]. However, data from a recent study showed that the exposure of this category of patients to any surgery is not associated with death [35].

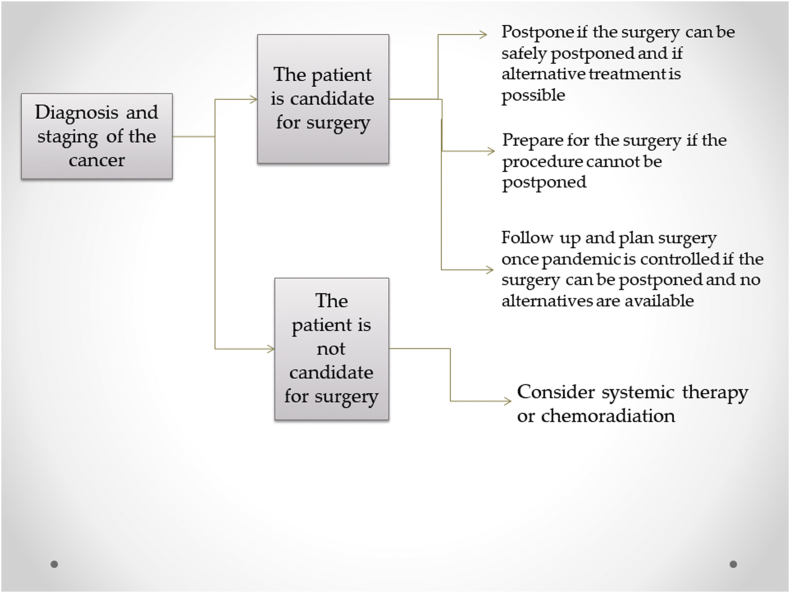

In some types of cancer, deferred surgical care may be considered [36,38]. Nevertheless, in some cases, the delay of the excision may have a great impact on an individual's prognosis and quality of life [[39], [40], [41]]. The need to wait for the surgery may also increase anxiety rates among this specific category of patients [42]. Therefore, the decision of delaying or operating will be challenging and would require a multidisciplinary approach in order to consider all the aspects of each case, including the type and stage of cancer, the age, the physical status, the psychological issues, and the availability of alternative treatments. Fig. 3 summarizes the global approach that is being used in many centers to manage the treatment of newly diagnosed cases with solid tumors. Recommendations to address this issue consider many factors as access to resources, patients' aspects, and disease stage [30,[43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]]. Nevertheless, the knowledge and the decisions regarding cancer surgery are rapidly evolving every day. The Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO), as well as other societies and centers, is still appealing for a case-by-case approach in final decision making [43,53].

Fig. 3.

The general approach of managing newly diagnosed cancer patients.

In general, programmed interventions for an early-stage disease can be deferred in most cases. Furthermore, the application of alternative tools such as neoadjuvant therapies, when possible, has been encouraged by many scientific societies [43,54]. A study with observational data showed that careful selection of patients for elective breast cancer surgery, along with the rigorous application of in-hospital protective measures, could be associated with encouraging outcomes [55].

In all cases, patients should be provided with transparent information about the risks of delaying their surgical care [54]. However, it was recently admitted that postponing incident cancers surgeries for three to six months is expected to mitigate 19–43% of the survival years that can be gained by a rate of hospitalization equivalent to the rate of admissions for COVID-19 patients [56]. Therefore, some authors are now recommending not to delay the surgery for all patients and to ensure coordination among health authorities and professionals to ensure adequate resource allocation [56,57].

In terms of cancer emergencies, current data on the impact of timing is still scarce, but as of now, current recommendations advise to delay all the emergent procedures as far as possible [36]. COVIDSurg Collaborative has conducted a multicenter prospective cohort study to assess the outcomes of cancer surgery in COVID-19 patients. However, the study data have not been published yet. This study will provide guidance for surgeons on the outcomes and risks of cancer surgery in COVID-19 patients.

Moreover, in order to reduce the risk of contamination among this population, there were some interesting initiatives such as the neuro-oncological hub, which is used to achieve conference calls and to share neuro-radiological imaging data. This platform is now used to categorize patients according to the disease severity in order to decide on the rapidity and the modality of surgical care [58]. Another hub structure was established for colorectal cancer cases [18]. In addition to these measures, some experts recommended the postponement of post-cancer surgery face-to-face consultations and replacing them with teleconsultation [59]. To sum up, many considerations should be taken in the management of cancer surgery during this era, and enhanced research work is urgently needed in order to understand the consequences of surgical delays and to establish evidence-based approaches to ensure optimal care for patients who require surgery.

4.7. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the surgical staff

Since WHO has raised the assessment of the global spread and risk of COVID-19 virus to “very high” and after 231,000 deaths had occurred in more than 200 countries and after the sudden increase in confirmed cases and the possibility of transmission via many routes with the vulnerability of surgeons in getting an infection during the long periods of contact with patients, tremendous stress and anxiety states affected the mental health of the surgical medical staff [60].

The surgical medical staff of Baoshan Branch of Shanghai Shuguang Hospital compared the anxiety, depression, dream anxiety, and SF-36 Quality of life scales among the front-line hospital staff before and after COVID-19 outbreak and found that all the scores after the outbreak were significantly higher (P < 0.001) [60].

It is not applicable to test all the patients in emergency rooms for COVID-19. This puts surgeons and anesthesiologists in danger of being infected during intubation or other invasive procedures. This represents a huge psychological burden on medical staff and on their families, as well [61]. Therefore, it is essential to pay attention to the mental health of medical personnel, which may negatively affect their critical medical decisions. Surgical medical staff is also one of the forces to resist the pandemic, so adequate rest and early psychological intervention measures should be provided [62].

4.8. Surgical training and the role of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic

Over 3 million cases of COVID-19 have been documented across a total of 210 countries at the time of writing this article. This pandemic is challenging the infrastructure of medical education in light of the recommendations of social distancing and virtual education by CDC. Although medical education is considered a core mission of academic medical centers, an era of expanding usage of smart technology for distance learning, in which social distancing seems the most effective measure, has begun [[62], [63], [64]].

In the USA, all non-essential elective surgeries and procedures are postponed and limited only to non-deferrable procedures. This is reducing surgical opportunities for residents in some departments (e.g., dermatology, urology, …etc.) and increasing others (e.g., trauma, intensive care units). In Europe, urology residents do not have the opportunity to carry out clinical activities nor to be guided as the senior and expert physicians are engaged in emergency management to reduce the operative time and the risk of complications. Most facilities are minimizing participants in any operation to essential personnel only [65,66].

Clinical discussions and the department's meetings were canceled to avoid gathering. The safety of laparoscopic and robotic surgical procedures started to be questioned. Since World War II, the Annual Meeting of American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) was never canceled but for this first time. Exams administered by many universities and institutes like the American Board of Neurological Surgery were postponed. In addition, institutional suspensions of critical research activities are progressing [65].

There is a dilemma with maintaining surgical resident education while providing a safe environment for residents, educators, and patients. Online platforms offering video teleconferencing, lectures, case conferences, journal clubs, and audible podcasting are the main methods in this new era of Telemedicine. Visitors to online 3D neurosurgical atlas increased by more than 20% since the COVID-19 outbreak, 45% of visitors between 25 and 34 years old, mostly medical students and residents whose learning is affected by the global pandemic. The Facebook group titled “ABSITE Daily” members increased from 27 to 237 with more than 120 daily views. This group provides daily practice questions and surgical-related topics virtual discussion about preparing residents for the American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination (ABSITE). In Italy, doctors checked electronic records of patients and picked up cases whose appointments should not be delayed. Consultations were done via phone mainly or face-to-face visits in some cases. Forty-five percent of scheduled consultations were canceled. History taking, formulating the management plan, discussing the case, and counseling can be done via video conference, so the lecturer can see who is currently attending and respond immediately to a question, which gives the feel of an in-person meeting from a safe distance [63].

5. Conclusion

Delivery of surgery during this critical period of the COVID-19 pandemic is imposing plenty of challenges on surgeons and surgical practice. It affected nearly all aspects of surgical procedures, scheduling, and staffing. Special precautions to prevent the viral spread and decrease postoperative complications were therefore taken before, during, or after surgeries. New treatment and teaching approaches emerged in response to the pandemic. However, research efforts are still needed to understand the impact of the pandemic and to make evidence-based decisions on performing the procedures. Last, psychological support and training platforms are necessary to enhance the performance of the surgical team.

Ethical approval

Our manuscript is a narrative review, so there are no patients.

Sources of funding

No funding was received for this work.

Author contribution

All of the authors contributed in all the phases of preparing this scoping review.

Trial registry number

Our manuscript is a narrative review, so there are no patients.

Guarantor

Ahmed Negida, MBBCh.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank COVID-19 MENA Research Response Team for their support and coordination of this project.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (Who) March 11 2020. Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report-51.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10 Available at. :, Last accessed May 12 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) April 7 2020. Adult Elective Surgery and Procedures Recommendations: Limit All Non-essential Planned Surgeries and Procedures, Including Dental, until Further Notice.https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-elective-surgery-recommendations.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for disease control and prevention (CDC) CDC's recommendations for 30 day Mitigation Strategies for Santa Clara County, California, based on current situation with COVID-19 transmission and affected health care facilities. [Internet] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/Santa-Clara_Community_Mitigation.pdf Available at:

- 4.The American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) March 20, 2020. New Recommendations Regarding Urgent and Non-urgent Patient Care.https://www.entnet.org/content/new-recommendations-regarding-urgent-and-nonurgent-patient-care-0 [Google Scholar]

- 5.American college of Surgeons . March 24, 2020. COVID-19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care.https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hildrew D.H. Prioritizing novel approaches to telehealth for all practitioners [internet]. From the American academy of Otolaryngology telemedicine committee. https://www.entnet.org/content/prioritizing-novel-approaches-telehealth-all-practitioners Published March 18, 2020, Available at:

- 7.Zarrintan S. Surgical operations during the COVID-19 outbreak: should elective surgeries be suspended? Int. J. Surg. 2020;78:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.005. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 14] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151(4) doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. 264-W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Society of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (ESTES) Recommendations for trauma and emergency surgery preparation during times of COVID-19 infection. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01364-7. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 17] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saadi R.A., Bann D.V., Patel V.A., Goldenberg D., May J., Isildak H. A commentary on safety precautions for otologic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0194599820919741. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 14] 194599820919741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan Z., Phoon P.H.Y., Zeng L.A., Fu J., Lim X.T., Tan T.E. Response and operating room preparation for the COVID-19 outbreak: a perspective from the national heart centre in Singapore. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.03.050. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 29]; S1053-0770(20)30300-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ti L.K., Ang L.S., Foong T.W., Ng B.S.W. What we do when a COVID-19 patient needs an operation: operating room preparation and guidance. Can. J. Anaesth. 2020;67(6):756–758. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01617-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong J., Goh Q.Y., Tan Z. Preparing for a COVID-19 pandemic: a review of operating room outbreak response measures in a large tertiary hospital in Singapore. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth. 2020;67:732–745. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01620-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Givi B., Schiff B.A., Chinn S.B. Safety recommendations for evaluation and surgery of the head and neck during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780. [published online ahead of print, 2020 March 31] 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pichi B., Mazzola F., Bonsembiante A. CORONA-steps for tracheotomy in COVID-19 patients: a staff-safe method for airway management. Oral Oncol. 2020;105:104682. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104682. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 6] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forrester J.D., Nassar A.K., Maggio P.M., Hawn M.T. Precautions for operating room team members during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.03.030. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 2] S1072-7515(20)30303-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sica G.S., Campanelli M., Bellato V., Monteleone G. Gastrointestinal cancer surgery and enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) during COVID-19 outbreak. Langenbeck's Arch. Surg. 2020;405(3):357–358. doi: 10.1007/s00423-020-01885-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aminian A., Safari S., Razeghian-Jahromi A., Ghorbani M., Delaney C.P. COVID-19 outbreak and surgical practice: unexpected fatality in perioperative period. Ann. Surg. 2020:216. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuhara S., Rosati C.M., El-Dalati S. Acute type A aortic dissection during COVID-19 outbreak. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.008. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 22] S0003-4975(20)30594-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.COVIDSurg Collaborative Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 29] [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 June 9;:] S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Topf M.C., Shenson J.A., Holsinger F.C. Framework for prioritizing head and neck surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Head Neck. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hed.26184. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 16] 10.1002/hed.26184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.COVIDSurg Collaborative Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br. J. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11746. [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 12] 10.1002/bjs.11746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu G.Y., Lou Z., Zhang W. Several suggestion of operation for colorectal cancer under the outbreak of Corona Virus Disease 19 in China. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2020 Feb;23(3):9–11. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0274.2020.03.002. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stahel P.F. How to risk-stratify elective surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic? Patient Saf. Surg. 2020;14(8) doi: 10.1186/s13037-020-00235-9. Published 2020 March 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American College of Surgeons, American Society of Anesthesiologists . 2020. Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, and American Hospital Association, “Joint Statement : Roadmap for Resuming Elective Surgery after COVID-19 Pandemic; p. 9.https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2020/04/joint-statement-on-elective-surgery-after-covid-19-pandemic [Online]. Available. [Google Scholar]

- 26.American college of Surgeons . April 17, 2020. COVID-19: Local Resumption of Elective Surgery Guidance.https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/resuming-elective-surgery Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiseman S.M., Crump R.T., Sutherland J.M. Surgical wait list management in Canada during a pandemic: many challenges ahead. Can. J. Surg. 2020;63(3):E226–E228. doi: 10.1503/cjs.006620. Published 2020 May 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lisi G., Campanelli M., Spoletini D., Carlini M. The possible impact of COVID-19 on colorectal surgery in Italy. Colorectal Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1111/codi.15054. [published online ahead of print, 2020 March 30] 10.1111/codi.15054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma . March 17, 2020. Guidance for Triage of Non-emergent Surgical Procedures.https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/triage Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patriti A., Eugeni E., Guerra F. What happened to surgical emergencies in the era of COVID-19 outbreak? Considerations of surgeons working in an Italian COVID-19 red zone. Updates Surg. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s13304-020-00779-6. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pryor A. SAGES and EAES recommendations regarding surgical response to covid-19 crisis. March 30, 2020. https://www.sages.org/recommendations-surgical-response-covid-19/ Available at:

- 32.Gillessen S., Powles T. Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Urol. 2020;S0302–2838:30201–30203. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.026. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 17] 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335‐337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta V., Goel S., Kabarriti R. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Canc. Discov. 2020 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516. [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 1] 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuderer N.M., Choueiri T.K., Shah D.P. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;S0140–6736(20):31187–31189. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9. [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 28] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Saverio S., Pata F., Gallo G., Carrano F., Scorza A., Sileri P., Smart N., Spinelli A., Pellino G. Coronavirus pandemic and Colorectal surgery: practical advice based on the Italian experience. Colorectal Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1111/codi.15056. Accepted Author Manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma A., Malviya R., Kumar V., Gupta R., Awasthi R. Severity and risk of COVID-19 in cancer patients: an evidence based learning. Dermatol. Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1111/dth.13778. [published online ahead of print, 2020 June 8] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Harten M.C., de Ridder M., Hamming-Vrieze O., Smeele L.E., Balm A.J., van den Brekel M.W. The association of treatment delay and prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients in a Dutch comprehensive cancer center. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(4):282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samson P., Patel A., Garrett T. Effects of delayed surgical resection on short-term and long-term outcomes in clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2015;99(6):1906–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grotenhuis B.A., van Hagen P., Wijnhoven B.P., Spaander M.C., Tilanus H.W., van Lanschot J.J. Delay in diagnostic workup and treatment of esophageal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2010;14(3):476–483. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Harten M.C., Hoebers F.J., Kross K.W., van Werkhoven E.D., van den Brekel M.W., van Dijk B.A. Determinants of treatment waiting times for head and neck cancer in The Netherlands and their relation to survival. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(3):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson K.M., Christensen K.B., Ottesen B., Krasnik A. Diagnostic delay, quality of life and patient satisfaction among women diagnosed with endometrial or ovarian cancer: a nationwide Danish study. Qual. Life Res. 2012;21(9):1519–1525. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bartlett D.L., Howe J.R., Chang G. Management of cancer surgery cases during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations. Ann. Surg Oncol. 2020;27(6):1717–1720. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08461-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Felice F., Petrucciani N. Treatment approach in locally advanced rectal cancer during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: long course or short course? Colorectal Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1111/codi.15058. [Published online ahead of print, 2020 April 1] 10.1111/codi.15058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueda M., Martins R., Hendrie P.C. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward a common goal. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2020;1‐4 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7560. [published online ahead of print, 2020 March 20] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ciavattini A., Delli Carpini G., Giannella L. Expert consensus from the Italian Society for Colposcopy and Cervico-Vaginal Pathology (SICPCV) for colposcopy and outpatient surgery of the lower genital tract during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13158. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 8] 10.1002/ijgo.13158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stensland K.D., Morgan T.M., Moinzadeh A. Considerations in the triage of urologic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.027. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 9] S0302-2838(20)30202-30205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ficarra V., Novara G., Abrate A. Urology practice during COVID-19 pandemic. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 2020 doi: 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03846-1. [published online ahead of print, 2020 March 23] 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campi R., Amparore D., Capitanio U., Checcucci E., Salonia A., Fiori C. Assessing the burden of nondeferrable major uro-oncologic surgery to guide prioritisation strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from three Italian high-volume referral centres. Eur. Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.054. Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pellino G., Spinelli A. How coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak is impacting colorectal cancer patients in Italy: a long shadow beyond infection. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2020;63(6):720–722. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Çakmak G.K., Özmen V. Sars-CoV-2 (COVID-19) outbreak and breast cancer surgery in Turkey. Eur J Breast Health. 2020;16(2):83–85. doi: 10.5152/ejbh.2020.300320. Published 2020 April 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sullivan M., Bouffet E., Rodriguez-Galindo C. The COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid global response for children with cancer from SIOP, COG, SIOP-E, SIOP-PODC, IPSO, PROS, CCI, and St Jude Global. Pediatr. Blood Canc. 2020;67(7) doi: 10.1002/pbc.28409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.J. S. Downs , M. J.Wilkinson, D. E. Gyorki and D. Speakman Division of Cancer Surgery Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC, Australia DOI: 10.1002/bjs.11693.

- 54.Thoracic Surgery Outcomes Research Network Inc. COVID-19 guidance for triage of operations for thoracic malignancies: a consensus statement from thoracic surgery outcomes research network. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.03.005. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 4] S0003-4975(20)30442-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fregatti P., Gipponi M., Giacchino M. Breast cancer surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observational clinical study of the breast surgery clinic at ospedale policlinico san martino - genoa. Italy. In Vivo. 2020;34(3 Suppl):1667–1673. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sud A., Jones M., Broggio J. Collateral damage: the impact on outcomes from cancer surgery of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.05.009. [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 16] S0923-7534(20)39825-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang E.I., Liu J.J. Flattening the curve in oncologic surgery: impact of Covid-19 on surgery at tertiary care cancer center. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jso.26056. [published online ahead of print, 2020 June 2] 10.1002/jso.26056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cenzato M., DiMeco F., Fontanella M., Locatelli D., Servadei F. Editorial. Neurosurgery in the storm of COVID-19: suggestions from the Lombardy region, Italy (ex malo bonum) J. Neurosurg. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.3171/2020.3.JNS20960. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 10] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fakhry N., Schultz P., Morinière S. French consensus on management of head and neck cancer surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2020;S1879–7296(20) doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2020.04.008. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 11] 30098-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu J., Xu Q.H., Wang C.M., Wang J. Psychological status of surgical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;288:112955. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112955. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 11] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neto M.L.R., Almeida H.G., Esmeraldo J.D. When health professionals look death in the eye: the mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;288:112972. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112972. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 13] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tomlinson S.B., Hendricks B.K., Cohen-Gadol A.A. Editorial. Innovations in neurosurgical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: is it time to reexamine our neurosurgical training models? J. Neurosurg. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.3171/2020.4.JNS201012. [Published online ahead of print, 2020 April 17] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chick R.C., Clifton G.T., Peace K.M. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Surg. Educ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 3] S1931-7204(20)30084-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kogan M., Klein S.E., Hannon C.P., Nolte M.T. Orthopaedic education during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00292. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 8] 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Porpiglia F., Checcucci E., Amparore D. Slowdown of urology residents' learning curve during the COVID-19 emergency. BJU Int. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bju.15076. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 9] 10.1111/bju.15076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amparore D., Claps F., Cacciamani G.E. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on urology residency training in Italy. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 2020 doi: 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03868-0. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 7] 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]