The current pandemic caused by the acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has profoundly impacted nearly every aspect of society. While mitigation strategies have curbed the spread of the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, these policies have had deleterious effects on the United States (US) economy, leading to a large contraction in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Spending on healthcare services comprises a sizable portion of the GDP, reductions in GDP, driven by the current pandemic milieu, could potentially harm patients who still need timely, high-quality care. Given the potential patient care implications of decreased spending on healthcare, we aimed to assess how reduced spending on healthcare services affected GDP and to assess factors that contributed to this decline.

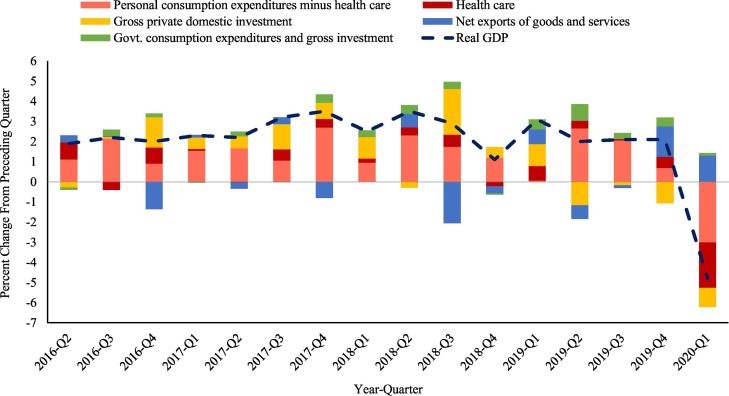

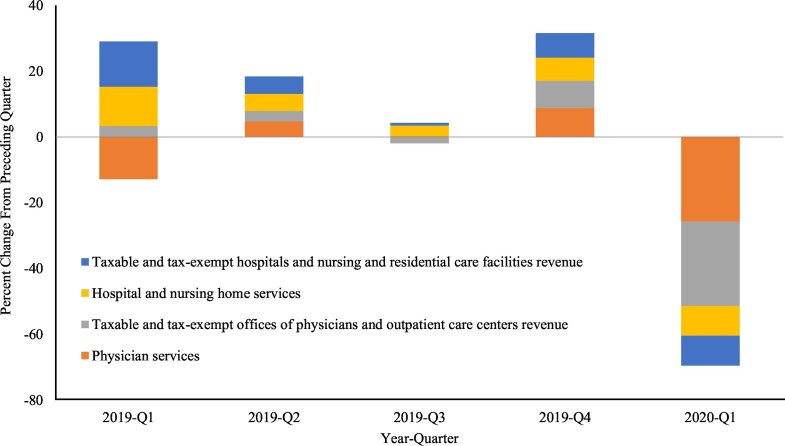

The GDP first quarter (Q1) 2020 advanced estimate report, published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), was examined to assess how spending on healthcare services during Q1 2020 compared the previous quarter and previous years. Real gross GDP decreased by 4.8% during Q1 2020, and this large contraction was due to COVID-19 and a variety of secondary factors [1]. Specifically, during Q1 2020, personal consumption expenditures decreased 5.26%, gross private domestic investment decreased 0.96%, net exports of goods and services increased 1.30%, and government consumption expenditures and gross investment increased 0.13%. However, the considerable contraction in personal consumption expenditures was largely driven by decreased spending on healthcare services (−2.25%) (Fig. 1 ) [1]. The BEA further divides spending on healthcare services according to current-dollar GDP into four main components, which also experienced large contractions. Physician services (−25.7%), and taxable and tax-exempt offices of physicians and outpatient care centers revenue (−25.7%) experienced the greatest decline from the preceding quarter followed by hospital and nursing home services (−9.0%), and taxable and tax-exempt hospitals and nursing and residential care facilities revenue (−9.0%) (Fig. 2 ) [1].

Fig. 1.

The percent change from the preceding quarter for the four main components of the real gross GDP (values are seasonally adjusted at annual rates). The health care component of personal consumption expenditures has been broken out to highlight its contribution to the percent change from the preceding quarter.

Fig. 2.

The percent change from the preceding quarter for the four main health care components of the current-dollar GDP (values are seasonally adjusted at annual rates).

The reasons for reduced healthcare spending are multifactorial. First, the demand for healthcare services unrelated to COVID-19 has likely decreased considerably due to reduced injury opportunity following the implementation of stay-at-home orders (e.g., reduction in motor vehicle collisions, reduction in sports-related trauma, and a reduction in certain types of crime) [2]. Furthermore, the pandemic has created a climate of fear, causing patients with medical conditions to be hesitant about seeking emergency care [3]. This worrying trend is highlighted by a reduction in hospital admissions for acute strokes and STEMIs [4,5]. Individuals suffering from psychiatric symptoms and victims of domestic violence also appear less willing to seek medical care due to COVID-19 related fears [6,7]. These findings are also corroborated by data indicating that emergency department visits declined 15% in March 2020 compared to March 2019 [8].

To reallocate resources and reduce the nosocomial spread of COVID-19, many hospitals and physician practices have postponed elective procedures and closed outpatient centers. Approximately 30% of inpatient hospital revenue is generated from elective procedures. The financial strain created by the pandemic is likely most severe among hospitals that depend on elective procedures as a primary source of revenue [9]. In addition, some hospitals are incurring losses from treating an increased number of uninsured patients with COVID-19 due to the current surge in unemployment. The cost of treating uninsured patients is further illustrated by a Kaufman Hall report that found hospital bad debt and charity increased 13% in March 2020 compared to the same time last year [8].

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the financial solvency of US hospitals is considerable. However, many rural, safety-net hospitals appear to be most at risk since over 400 rural facilities are currently vulnerable to closure based on financial and operational metrics [10]. In response to these growing financial concerns, the US has enacted the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act which will contribute $100 billion to reimburse hospitals and other health care organizations combating the COVID-19 pandemic and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act which will contribute an additional $75 billion for the same purpose [11,12].

Overall, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating effect on the American economy and personal health and has created many unique challenges for hospitals and physician practices. While all healthcare organizations are experiencing financial strain in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, lost revenue from emergency department visits, and elective procedures have put undue strain on many rural, safety-net hospitals. Currently, government relief funding is beginning to be dispersed; however, it remains unclear if these measures will be sufficient to prevent the closure of at-risk hospitals. Hospital leadership and policymakers need to take steps to rebuild America's economy and healthcare system to ensure lifesaving treatment is available for all patients during these trying times.

Funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bureau of Economic Analysis . Bureau of Economic Analysis; Suitland, MD: 2020. Gross domestic product, 1st quarter 2020 (advance estimate) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Govern P. Vanderbilt University Medical Center; 2020. Fewer accidents, social distancing spur drop in trauma volumes. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boserup B., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine; 2020. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits and patient safety in the United States. In press, Published online: June 5, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markus H.S. EXPRESS: COVID-19 and stroke-a global world stroke organisation perspective. Int J Stroke. 2020;1747493020923472 doi: 10.1177/17474930211006435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zitelny E., Newman N., Zhao D. STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic - an evaluation of incidence. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2020;107232 doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2020.107232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Usher K., Bhullar N., Durkin J., Gyamfi N., Jackson D. Family violence and COVID-19: increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(4):549–552. doi: 10.1111/inm.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro V.M., Perlis R.H. Impact of COVID-19 on psychiatric assessment in emergency and outpatient settings measured using electronic health records. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11346. [preprint from medRxiv and bioRxiv], Posted 2020 Apr 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufman Hall . Kaufman Hall; 2020. National hospital flash report; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss A., Elixhauser A., Andrews R. HCUP Statistical Brief #170. February 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. 2014. Characteristics of operating room procedures in U.S. hospitals, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chartis Center for Rural Health . The Chartis Group; 2020. The rural health safety net under pressure: rural hospital vulnerability. [Google Scholar]

- 11.CARES Act . 2020. 116th Congress ed. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act . 2020. 116th Congress ed. [Google Scholar]