Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 is a new member of coronaviruses that its sudden spreading put the health care system of most countries in a tremendous shock. For controlling of the new infection, COVID-19, many efforts have been done and are ongoing to defeat this virus in the combat field. In this review, we focused on how the immune system behaves toward the virus and the relative possible consequences during their interactions. Then the therapeutic steps and potential vaccine candidates have been described in a hope to provide a better prospective of effective treatment and preventive strategies to the novel SARS-CoV in near future.

Abbreviations: WHO, World Health Organization; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine protease 2; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; FCN1, ficolin 1; SPP1, secreted phosphoprotein 1; FABP4, fatty acid-binding protein 4; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; STING, stimulator of interferon genes; GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IP-10, interferon gamma-induced protein 10; MCP-3, monocyte chemotactic protein-3; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-1ra, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen; Fao2, alveolar oxygen fraction; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; MIP-1A, macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; FC, fragment crystallizable region

Keywords: CVID-19, Immune response, Cytokine storm, Inflammation

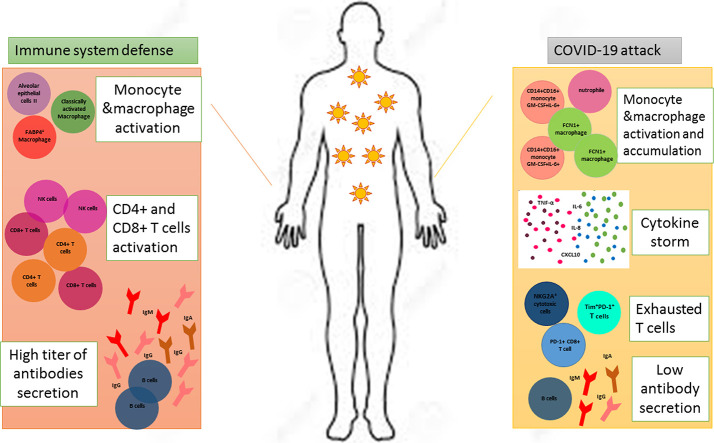

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Since December 2019, there has been an outbreak of coronavirus (known as SARS-CoV-2), started in Wuhan, China and has quickly disseminated around the world [1]. The WHO has announced the new coronavirus (CoV) infection as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC, January 30, 2020) and named it coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). Based on genome analysis, SARS-CoV-2 is similar to SARS-CoV which belongs to β-lineage coronaviruses [2] and as a zoonotic virus it possibly originates from bats [3]. SARS-CoV-2, like SARS-CoV, binds human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) protein to infect various cell types [4] especially lung, heart, kidney and testes [5]. Indeed, the full entry is achieved by a cellular serine protease named TMPRSS2 that prepares the effective form of viral antigenic S protein [6]. However, new studies referred to CD147 as another novel rout to invade host cells by the virus [7]. CD147 is a transmembrane glycolprotein belongs to immunoglobulin super family which highly expresses in inflamed tissues, virus-infected cells and tumor tissues [[8], [9], [10]]. According to the study performed by Guan et al. the COVID-19 is less severe and less fatal in comparison to the SARS but some patients especially elderly with underlying co-morbidities like cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and hypertension are susceptible to develop more severe symptoms or even death [11]. Similar to SARS-CoV infection, the clinical symptoms of COVID-19 vary, ranging from asymptomatic to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [[12], [13], [14]].

It is not completely understood why some patients develop severe but others have mild disease or even stay asymptomatic. Maybe, the ways immune system encountering with the virus will answer the question and better understanding of all aspects of immune-virus interactions help the management of the infection.

Obviously, immune system is the greatest player dealing with all types of infections. Nonetheless, in the case of COVID-19 it is somehow blurry whether the activation of host immune responses is protective or destructive. A well-contribution of innate and adaptive immune responses may rapidly take control of the virus and clear infected particles from the body, while dysregulated immune responses result in viral spreading, multi-organ failure and high mortality [15]. Thus, deep investigations of immunological events that take place during COVID-19 and of relative cellular or molecular mechanisms seem to be helpful. Although, researchers are attempting these days to develop vaccines and analyzing anti-viral drugs in clinical trials [16], there are no effective prophylactic and clinical treatment options for COVID-19, yet.

This study aimed to describe the pathogenesis and protective roles of immune responses in COVID-19 in the terms of innate and adaptive immunity. Besides, potential immunological treatment tools and preventive approaches have been mentioned.

2. Innate immunity in COVID-19

To elicit the primary antiviral response, innate immune cells as professional sentinels recognize the invasion of the virus by binding to immunogenic antigens like the RNA of coronavirus. This recognition triggers signaling cascades to express type I interferon (IFN-I) and other pro-inflammatory cytokines defending against viral infection at the entry site. The IFN-I production plays a crucial role in inducing effective innate immune response and limiting viral replication [17]. it has been declared that SASR-CoV-2 can exploit innate immune system to release a huge number of cytokines and chemokines that end in dyspnoea and respiratory failure [18]. Based on literatures, SARS-CoV using various strategies can interfere with IFN-I production and suppress the IFN-I response to the viral infection which this intervention is closely related to the severity of the disease [17,19,20]. For SARS-CoV-2 similar ways has been speculated to suppress IFN-I response and disturb host innate immunity which results in failure of viral controlling at early phase of infection [21].

However, according to researches on previous coronaviruses, active viral replication later stimulates hyperproduction of IFN-I and influx of neutrophils and macrophages that are the main sources of pro-inflammatory cytokines [19]. In SARS infected mice model, rapid replication of virus finally causes a delayed IFN-I production and induces severe disease by increasing accumulation of pathogenic macrophages resulting in lung immunopathology, vascular leakage, and defective T cell responses [22]. With similar of SARS-CoV-2 with SARS, it is probable that delayed IFN-I production and loss of viral control occur in an early stage of the disease which promote massive inflammatory reactions in the pulmonary track [13].

Interestingly, it has been discovered that ACE2 receptor is a human interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) that SARS-CoV-2 may imply species-specific interferon-driven enhancement of ACE2 to establish infection [23]. Moreover, Blanco-Melo et al. observed at a low multiplicity of infection (low-MOI) in A549 lung alveolar cells expressing ACE2, high levels of replication could be occur just in the absence of IFN-I and III induction. Indeed, it seems at a low-MOI, the virus is not a powerful inducer of IFN-I and III secretion, in apposite to high MOI condition [24]. However, deeper investigations is needed to explain how this dynamic affects COVID-19 consequences.

These findings magnify the importance of the innate immunity efficacy as a critical factor in COVID-19 outcomes and necessitate further researches on cells or mediators involve in this response.

2.1. Macrophage

Macrophages are one of the important parts of the innate immunity which possess heterogeneous subsets including monocyte-derived macrophages and tissue resident population with a variety of characteristic features from (classically activated macrophage) M1 to (alternatively activated macrophage) M2 like phenotype [21]. According to the literature performed by Wang et al. alveolar macrophages with SARS-CoV-2 infection express ACE2 receptor which eventuates in activation and secretion a large number of inflammatory cytokines following binding to the virus along with an extensive macrophage and monocyte infiltration into the lung [25]. In another study conducted by Zhou et al. it is mentioned that inflammatory monocytes (CD14+CD16+) which were GM-CSF+IL-6+, increased in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. These monocytes were capable of lung migration in which they could further differentiate to macrophages or monocyte-derived dendritic cells [26]. In parallel, Zhang et al. analyzed peripheral blood monocyte cells (PBMCs) samples of COVID-19 individuals and revealed no changes in monocyte frequency. However, a significant difference in morphology and marker expression of these cells was observed with an inflammatory phenotype as a result of IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α secretion along with the higher expression of CD11b, CD14, CD16, CD68, CD80, CD163 and CD206 on their surfaces to create the first highly inflammatory environment during disease process [27]. The accumulation and activation of macrophages and monocytes trigger uncontrolled cytokine storm especially in severe cases that leads to the shift of M1 to M2 phenotype of alveolar macrophages and further contribute to the inflammatory injuries and fibrosis of respiratory tracts [25,28]. In convinced with this idea, a group of macrophages has been described in patients with SARS-CoV-2 express genes related to tissue repair and fibrosis generation like that is seen in liver cirrhosis [29]. Therefore, the pathogenicity of activated macrophages in lung might be associated with fibrotic complications along with acute inflammation which are pointed out in COVID-19 patients with ARDS [30]. However it is not obvious how SARS-CoV-2 interferes with macrophage/monocyte functions and employs them to survive and infect other cells. Additional researches are needed to come up with some logical reasons.

Recently, Reyfman and colleagues have been identified four groups of lung macrophages classified by FCN1, SPP1 and FABP4 markers. Group 1 & 2 are monocyte-derived FCN1+ macrophages that produce abundant inflammatory chemokines and activate the interferon-stimulated genes cooperating in hyper-inflammation process [31]. Referring to the study conducted by Liao et al., FCN1+ macrophages are dominated in the severely damaged lungs from COVID-19 patients with ARDS [32]. Group 3 was discovered as SPP1+ macrophages which neutralize the inflammatory consequences of FCN1+ cells and represent a probable pro-fibrotic feature [31]. However, FABP4+ alveolar macrophages (AMs), the group 4, were a predominant macrophage subset in COVID-19 patients with mild disease although they were completely absent in severely infected patients [32]. According to researches, FABP4+ AMs play an important role in metabolizing lipid surfactant [21] induced by the cytokine granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [33] and it was supposed that the absence of AMs in severely infected cases may contribute to lung failures.

Apart from the immune cells, it is declared that alveolar epithelial cells contribute in innate immunity against COVID-19 in the lung. It has been shown that SARS-CoV-2 preferentially infects alveolar type II (ATII) cells which involve 5–15% of the lung epithelium and express ACE2 receptor on their surfaces intensively [6,[34], [35], [36]]. ATII cells are also able to synthesize and secret surfactant protein A (SP-A) which has a crucial role in surfactant metabolism and lung innate immunity [37]. According to the research of Qian et al. SARS-CoV is able to propagate in ATII cells until the cells undergo apoptosis or die and the viral particles are released in adjacent area [38]. ATII cells can activate and produce inflammatory cytokines through expressing Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and recruit or activate other immune cells, including macrophages and neutrophils. Besides, ATII cells and alveolar macrophages coordinate inflammatory responses which may underlie lung injury associated with COVID-19 [[34], [35], [36]].

2.2. Neutrophils

Gao et al. showed that 29 out of 75 COVID-19 patients had an increase in their neutrophil percentage [39]. In contrast, Ying Xia et al. showed that neutrophil percentage of severe COVID-19-patients drastically declined [40]. In a comparative point of view, this difference in neutrophil percentages could be explained in this way that Gao et al. did not consider patients in clinically severe and mild group but mentioned that in IL-6 elevated patients (n = 14), whereas in Ying Xia et al. study, major population of patients were severe cases and showed a pattern of immune dysfunction. In a cohort study with 61 COVID-19 patients the importance of neutrophils was noticed in Neutrophil/Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a prognosis factor. Indeed, the high frequency of neutrophils in blood leads to vast neutrophil infiltration into lungs versus low existence of lymphocytes in the periphery representing immune dysregulation by the virus in severe condition. However, Xin et al. suggested that the application of neutrophil to CD8+T cells ratio (N8R) must be carefully considered as more accurate and valuable prognostic index for estimating of COVID-19 severity in patients because CD8+ T cells are the main subpopulation of lymphocytes that decreased in this case [41]. Xianbo et al. evaluated the prognosis value of NLR in a more comprehensive view. They defined a cut off value of ≥3.13 for NLR and an age range of ≥50 as an early sign of developing severe disease which might become life-saving by early disease handling [42].

An important functional aspect of neutrophils in COVID-19 is neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). In general, NETs blood level in ARDS patients is higher which is related to higher severity and mortality [43]. Kanthi and knight et al. showed that in a population of 50 hospitalized COVID-19 patients the laboratory markers of NETosis including cell free DNA, myeloperoxidase (MPO)-DNA and citrullinated histon H3 (Cit—H3) increased dramatically Besides, cell free DNA manifested a strong correlation with inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer and lactate dehydrogenase. Surprisingly, they showed that COVID-19 sera induce NET formation in neutrophils of healthy individuals and defined a pro-NETotic state for severe cases. In this regard, factors like virally damaged epithelial cells, activated platelets or endothelial cells and inflammation related cytokines announced possibly responsible [44].. Considering all these studies, neutrophils act as the main cells in predicting the COVID-19 outcome in infected ones, so identifying the precise mechanism and changes seems to be useful.

3. Adaptive immune response to COVID-19

In a routine viral infection, the heaviest burden of defense responsibility is on cellular immunity especially T cells and in COVID-19 it is not exceptional. Until now, the most prominent feature in almost all of COVID-19 patients is lymphopenia caused by extensive lymphocyte death. A more accurate view in this population of cells shows significant decline in T cells which mainly cleared the infection in parallel with enhancing humoral immunity. The main question in this field must be that how and by which mechanism this, probably, viral immune evasion takes place?

Hong Ming et al. suggested that the Time-lymphocyte model (TLM) should be considered in hospitalized cases of COVID-19 in order to prevent possible over/under treatment incidences. According to their model, 2 weeks after disease initiation, if the LYM% raises over 20%, cases will be considered moderate whereas cases with lower than 20% lymphocyte count must be classified as severe cases. In the third week of symptomatic disease the severe cases that have higher than 5% lymphocyte count might get better, otherwise the disease will cause mortality in patients [45]. Lymphocytes which are mentioned as arms of adaptive immunity, act in humoral and cellular responses to stand in front of SARS-CoV-2 attack which we will discuss in detail.

3.1. Humoral immunity

As it is well known, B cells could activate and defense against viruses so that some studies have detected binding and neutralizing antibodies in SARS-CoV infections and reported robust antibody responses in severely infected SARS patients [46,47]. However, the dynamics of the antibody secretion in COVID-19 patients are under investigation due to antibodies are considered as potential diagnostic tools to complement Real-time PCR assay.

Referring to the clinical reports and primary time course of COVID-19, the disease is detected after 1–2 days following the symptoms representation, peaking 4–6 days later and finally clearing within 18 days [48]. Based on evidences, seroconversion is obvious at approximately day 18 with maximum anti-virus IgG titer measured 20 days after disease onset. This process with better knowledge about the dynamics of immunological events during COVID-19 can help health authorities to manage the disease outbreak and confer a deeper prospective of protective strategies to eradicate the infection [49].

In a study performed by Xiao et al. the antibody profile of 34 SARS-CoV-2 patients during 7 weeks was analyzed in which all individuals were positive for IgM and IgG at week 3 after the onset of disease. The level of IgM decreased at week 4, 2 patients were negative at week 5 and 2 patients else at the end of observation (week 7). This result revealed the acute phase of infection lasts more than 1 month in most patients. Along with IgM decreasing, IgG level elevated from week 3 to week 7 representing the activation of humoral immune response to the infection [50]. In another study, Li Guo et al. profiled the early antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 using 208 plasma samples collected from 82 positive and 58 probable cases. The samples were examined by ELISA test on the recombinant viral nucleocapsid (rN) protein. Achieved results showed that IgM and IgA antibodies were detected 5 days after symptom onset while IgG was detectable on 14 days. It is declared that in comparison to real-time PCR the detection efficiency by IgM ELISA was higher after 5.5 days of symptom onset and once IgM ELISA assay combined with PCR, the positive detection rate significantly increased (98.6%) to diagnosis of COVID-19 [51]. Additional study on the dynamics of COVID-19 specific antibodies in 173 patients reported that, seroconversion occurred sequentially for total antibody, IgM and IgG with median time of 11, 12 and 14 days respectively. The receptor-binding domain (RBD) epitope of the S1 subunit was used to detect IgM by double recombinant antigens sandwich immunoassay and IgG antibodies were detected using recombinant NP antigen through indirect ELISA kit. Remarkably, the antibody detectability was lower than PCR test up to 7 days since the symptom initiation while raised gradually from day 8 to day 39 overtaking the PCR test. Surprisingly, the levels of viral RNA in patient's samples were found undetectable alongside the levels of total antibody were measured in the sera. These evidences highlight the extreme importance of combining molecular and serological tests to improve the sensitivity of diagnosis at different stages of the disease [52].

Recently, some researchers suggested antibody dependent enhancement (ADE) theory to explain the relationship between prior exposure and disease severity or death in some cases. According to these studies, it has been hypothesized that severely infected SARS-CoV-2 patients may have been primed by one or more other coronaviruses previously and due to antigenic epitope heterogenicity, the elicited antibodies might not completely neutralize the second infection and conversely form complexes with the second virus or virus-activated complement components that interact with the Fc or complement receptors on susceptible cells, thereby facilitating viral entry [[53], [54], [55]]. Previously, ADE has been investigated massively in dengue virus [[56], [57], [58]], HIV [59] and Ebola [53] infections. Based on SARS-CoV in vitro studies and mouse models, ADE dysregulates the immune response provoking cytokine surge, lymphopenia and inflammation-based injuries [54] in lung or other parts of the body in severely infected individuals [60,61].

Since ADE phenomenon requires prior infection to similar antigenic epitopes, Donnelly CA and co-workers revealed several epitopes on the SARS-CoV spike protein [62] that were similar but not identical to SARS-CoV-2 and these epitopes may responsible for ADE in COVID-19. In convinced with this achievement, Liu et al. discussed earlier during acute phase of SARS-CoV infection that anti-S-IgG modulates macrophage functions by decreasing TGF-β production meanwhile promoting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines which culminating in acute lung injury [63]. In another point of view, it has been declared some non-neutralizing Abs binding non-RBD regions in the S protein may result in an ADE of SARS-CoV infection, with harmful immune response [64]. Notably, it has been mentioned that it is not necessary to have experience of a predominant priming virus, some other bat coronavirus strains [65] have been identified with higher homology to SARS-CoV-2 than SARS-CoV and when individuals were exposed to those viruses it might be considered as a regular common cold virus. Further researches are needed to exactly discover the mechanism of ADE in SARS-CoV-2 infection and its appropriate role in COVID-19 initiation and progression in order to introduce effective viral vaccines or antibody-based therapies.

3.2. Cellular immunity

Considering that ACE2 acts as main target receptor for SARS-CoV-2 and tonsil lymphocytes, besides lymph nodes express ACE2, T cells can be directly infected by virus. By keeping in mind that an upregulation of 13 apoptosis activating genes has been shown in SARS-CoV infected PBMCs, it seems as if an immunocompromised state in patients is a virus-directed mechanism [66]. The apoptosis of T cells might also happen because of an unusual lag in type I interferon response or the high amount of pro inflammatory cytokines that makes T cells sensitize toward apoptosis [19]. In a comparative point of view, Qin et al. suggested that due to low expression of ACE2 in T cells, they might not be susceptible to infection [67]. There is a need for further extensive investigation highlighting this issue.

Haiming et al. has widely analyzed T cell populations in COVID-19 infected cases and reported that the decline of CD4+T lymphocytes was seen in either ICU/non-ICU patients but CD8+T population dropped remarkably in ICU patients. Also, in infected individuals both CD4+ and CD8+T cells were CD69, CD38 and CD44 positive that showed they were in activated status. Presence of OX40 as a marker of high cytokine secretion on CD4+ population and 4-1BB as an indicator of cytotoxic activity of CD8+T population was mentioned in their study. On the other side, they showed a rise in Tim+PD-1+ co-expression phenotype in ICU patients which reflects immunologic exhaustion in severe cases. Moreover, they showed that severely ill ICU individuals had a high frequency of GM-CSF+ IL-6+ CD4+T cell population and IFN-γ+ GM-CSF+ T helper (Th) 1 cells that create a hyper-inflammatory condition [68].

The exact protective or destructive function of CD4+T cell subset has not been characterized yet, but it is worth to mention that in a case report study the frequency of CCR6+Th17 subset increased which sounds to be responsible for immune related tissue injury along with cytotoxic T cells [69].

3.2.1. T cell response in lung

Chen J et al. showed that in an animal model of SARS- CoV, depletion of CD8+T cells by the time of infection had not any specific impact on viral clearance or replication but in opposite, CD4+T cells depletion leads to interstitial pneumonitis which was due to immune system activation and the clearance of virus from the lung environment became time-consuming [70]. In addition, Zhao JM et al. exhibited that the main population of inflammatory cells infiltrated to lung were CD8+T cells that cause immune-induced lung injury by means of virus killing pathways [71]. It has been shown that SARS-CoV is not able to infect effective T cells but through infecting antigen presenting cells (APCs), can interfere with T cell priming and migration that in turn leads to declining of virus-specific T cells in the lung [72,73].

Despite all efforts that the immune system makes to defeat SARS-CoV-2, the virus like other known viruses for sure, has its own ways to hide or evade from immune system. As COVID-19 is highly resembled to SARS-CoV, there might be some overlapping mechanisms. The most recommended pathways are: 1. Induction of immune cell apoptosis especially lymphocytes and T cell populations. 2. Triggering cytokine storm which leads to immune system malfunction besides virus indirect apoptosis of immune mediated cells. 3. Impairment of antigen presenting pathway and non-optimal T cell activation. 4. Possible viral mutation tendency especially in MHC-I presentation regions [74]. 5. Changing T cells from immune-activated to immune-exhausted type [75].

Indeed, SARS-CoV-2 acts by establishment of an immune system anarchy which causes devastating sequence of events that end in a dramatic mortality.

3.2.2. Cytokine storm syndrome (CSS)

It has been documented that the uncontrolled systemic inflammatory response mainly exerted by pro-inflammatory cytokines causes vigorous multiple tissue damages and organ failures which finally leads to death in severely infected cases [69,76]. In consistent with this idea, recent report in Lancet showed that ARDS is the major reason of death in COVID-19. In fact, ARDS is the common immune-pathologic event for SARS-CoV-2 by triggering cytokine storm [69]. Xin et al. has been revealed that the cytokine level of IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, and IFN-ϒ in severe COVID-19 patients reached the highest level during the first week of disease [41]. Ying Xia et al. has been evaluated 48 cytokines in plasma samples of 53 COVID-19 cases in severe/moderate stage and posed that IP-10, MCP-3 and IL-1RA had the highest rate, which were associated with PaO2/Fao2 [40]. In a study performed by Xiong et al. on 19 patients, the transcriptional signatures of host inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 infection has been characterized. They analyzed RNAs isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) specimens of COVID-19 patients and emphasized on the correlation of COVID-19 pathogenesis with increased cytokine release such as CCL2(MCP-1), CXCL10 (IP-10), CCL3 (MIP-1A), and CCL4 (MIP1B) [77]. These studies revealed that that the more pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines secreted, the more severe disease could be expected.

Recently, it has been shown that viral load in respiratory tract of clinically ill patients and asymptomatic carriers are almost the same [48]. Jinya et al. exhibited that in COVID-19 patients viral load in serum should be considered as a poor prognosis index in critically ill group because by an up to 10 fold increase in IL-6 elevation in severe cases, it may lead to CSS and ultimately cause multi-organ failure [78]. To support this study, Wenjun et al. analyzed 11 critically ill pneumonia patients with COVID-19 and found out 72.7% individuals suffered from cytokine release syndrome-like (CRSL). They also identified that increased IL-6 in PBMC was the leading risk factor for CRSL. Indeed, IL-6 considered as a primary indicator of CRSL in COVID-19 patients with pneumonia [79]. In total, among different studies, IL-6 has been declared as the most elevated factor that acts as the director of CSS. Thus the main question needs to be answered in this subject area is which immune cells or events might be the early driver of massive IL-6 secretion? Neutrophils and NETosis have been accused for this catastrophe. Egeblad et al. proposed a vicious cycle of uncontrolled inflammation between NETs and macrophages among COVID-19 severe cases, in which NETs amplified macrophages to produce massive IL-1β and vice versa. Moreover they mentioned the capability of neutrophils for shedding soluble IL-6Rα in response to IL-8 stimulatory effects that leads to trans-signaling and creation of an uncontrolled-progressive pro- inflammatory state which is a common finding in SARS-CoV-2 cases [43]. Eventually, CSS leads to multi-organ failure as an unwanted life-threatening happening.

3.2.3. T cell response to COVID-19 in mild and severe clinical manifestation

In a non-severe COVID-19 patient, T cell evaluations have been shown a dramatically increase not only in frequency but also in function especially in activated CD8+T cells and in a less degree in activated CD4+T lymphocytes on day 7 post infection. It's interesting that across with this rapid increase of immune cells, a vast decline of SARS-CoV-2 was detected in nasopharyngeal or sputum specimens by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase-chain-reaction (rRT-PCR). On the other hand, the measurement of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines showed no sign of cytokine storm during the symptomatic phase of disease and the cytokine levels showed an inverse model of level changes in contrast to T cells [80].

In a comparison between severe and moderate COVID-19 patients, Qin et al. declared that in severe cases a worse decline in absolute number of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells along with regulatory T (Treg) cells was observed which was accompanied by decreased IFN-γ secretion mainly by CD4+T cells. IL-2R, IL-10 and TNF-α were quietly higher in severe cases by the time of admission which brings out the fact of cytokine storm phenomenon direct effects on disease severity [67]. It is worth to note that similar to non-severe cases of Kedziereska et al. study, the frequency of HLA-DR+CD8+Tcells were higher in severe cases of Qin et al. study. They considered this group as a population of Treg cells which express CTLA-4 and induce suppressing effects on activated T cells [80]. This population of T cells was previously introduced by Aluvito L et al. [81]. In another study, Yong Gao et al. announced that decreasing CD4+T cells is the most significant event in patients with SARS-CoV-2 which might be related to highly elevated IL-6 secretion, as a causative agent of T cell death and partial immunodeficiency [39]. Xin et al. has been investigated 40 COVID-19 patients (severe and mild) and declared that during the course of disease there was a sustained dropping in absolute T cell counts especially in CD8+ subpopulation and this decline as well as lymphopenia persists even weeks after symptom resolution [41]. In a large population of hospitalized patients IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α were highly over-expressed in ICU patients in comparison to non ICU cases of COVID-19 infected individuals which shows a contrary trend toward T cell count during the course of disease [75].

Yong wen et al. showed that in an evaluation of 522 confirmed COVID-19 patients who were further divided into ICU patients and non ICU patients, the T lymphocyte population was remarkably lower in ICU cases and this decrease showed a worse trend in aged cases. Interestingly, they revealed that in ICU admitted group the frequency of Tim-3 expressing CD4+Tcells and PD-1 expressing CD8+T cells was much higher than non-ICU cases of COVID-19. They pointed to the presence of IL-10, which is not only responsible for prevention of T cell proliferation but also has a well-accepted role in T cell exhaustion process [75]. It has been demonstrated by Zheng et al. that NK and CD8+T cells became functionally exhausted with the increased expression of the inhibitory receptor NKG2A, and reduced the ability to express CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α and granzyme B in COVID-19 patients. Whilst, the percentage of NKG2A+ cytotoxic lymphocytes diminished after patientʼs recovery which presented the role of NKG2A expression in the process of exhaustion and disease progression at early stages [82,83]. The role of innate immunity and adaptive response has been summarized in Fig. 1 .

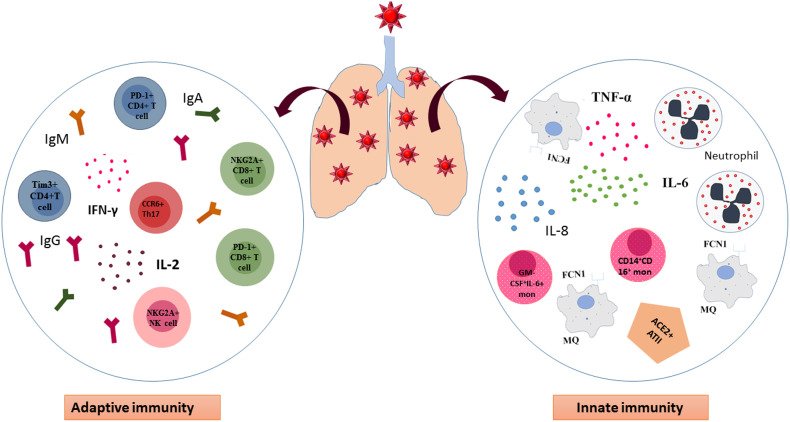

Fig. 1.

Innate and adaptive immune response to COVID-19. In the lung of patients with COVID-19 macrophages and monocytes as important players of innate immunity accumulate in the lung and over-express inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α leading to uncontrolled cytokine storm. Besides, alveolar epithelial cells type II through ACE2 receptors are able to bind SARS-CoV-2 and contribute in cytokine surge. On the other hand, adaptive immunity is not efficient enough to defeat the virus and the phenotype of T cells shift to exhausted one. CD4+ and CD8+T cells express PD-1 and Tim-3 on their surface in addition to NKG2A NK cells which are consider exhausted cells. However, CCR6+ T helpers (Th) 17 can accelerate the inflammation process and worsen tissue damage by secretion of inflammatpry cytokines and recruitment of neutrophils. MQ, Macrophage. Th17, T helper17.

4. Organ failures

The main clinical signature in severely infected COVID-19 patients is multi-organ failure which ultimately leads to rapid death by creating a complete imbalance in key organ tissues including lungs, heart, liver and kidneys. It has been declared that not only lung tissue but also gastrointestinal tract, vascular endothelial and arterial smooth muscle cells extensively express ACE2 on their surfaces so the organs can be infected by the virus instantly [84]. So it is essential to consider clinical investigations of SARS-CoV-2 in feces samples and the blockade of possible fecal-oral transmission. It has also been supposed that COVID-19 preliminary attack the lung parenchyma through binding ACE2 on host cells leading to intervention of renin–angiotensin system (RAS) and then severe interstitial inflammation of the lungs will happen [85].

Previous researches announced that pediatric populations possess strong innate immunity whereas the complement system and adaptive immunity are not mature enough [86]. Thus, it seems that children with effective innate immune system are able to block viral invasion at mucosal level and consequently manifest mild or even asymptomatic features following SARS-CoV-2 infection. On the Contrary, elderly population lacks effective innate immune system while the complement system is improved in this age. Remarkably, adaptive immune system develops gradually from childhood to adulthood however weakens among elderly [87,88]. As a result of defective innate immunity and robust complement activation induced by SARS-CoV, aged cases experience a severe progressing pneumonitis [89,90]. Hence, acute hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is more common in aged. Comparatively, healthy adults with normal adaptive immunity regulate inflammatory reactions better and show a sub-acute HP [91]. It is worth to mention that aside from handy innate immunity, other factors in children are responsible for COVID-19 mild or asymptomatic manifestations such as higher lung pneumocyte ACE2+ proportion to elderlies, trained immunity as a presentation of innate memory and higher lymphocyte frequencies, specifically NK cells [92].

Another organ that may be affected by COVID-19 is liver due to cytokine surge. Findings show that bile duct epithelial cells derived from hepatocytes stimulate ACE2 over-expression in liver tissue through compensatory proliferation that leads to hepatic tissue injury in COVID-19 patients with pneumonia [93]. Fu sheng et al. commented that during their evaluation between different studies, severe cases especially those admitted to ICU, liver injury was a more common phenomenon than mild cases. The presence of viral RNA in blood or stool samples of 2–10% of COVID-19 cases and also expression of ACE2 on cholangyocytes were all possible witnesses that liver is one of the organs under COVID-19 attack [94]. Laboratory observations performed by Yong Gao et al. showed markedly liver dysfunction in COVID-19 patients by increasing alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). They also found out the levels of Troponin I and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were higher in the severe infection [39]. Moreover, the decline level of platelets and longer activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) with a jump in creatinine level with renal failure altogether confirmed the extensive devastating effects of Multi-organ failure in COVID-19 [39].

In addition, COVID-19 affects cardiovascular system reversely as a result of exacerbated systemic inflammatory response and immune system disorders during disease progression [95]. Cheng long et al. presented that heart pericytes are the main virus target in the heart due to high ACE2 expression that leads to capillary endothelial and microvascular malfunction. It is interesting that patients with basic heart failure showed an increased RNA or protein expression of ACE2 which is possibly the main cause of severe problems in this group [96]. Fox et al. have been observed the COVID-19 severe cases autopsies and reported valuable cardio-pulmonary findings. In lungs, they revealed aggregated CD4+T cell populations near thrombotic small vessels accompanied with dramatic hemorrhage. They defined this phenomenon with the existence of activated CD61+ lung resident megakaryocytes which resulted in fibrin deposits and platelet derived clots. This group mentioned another finding which was not common between samples, degenerated neutrophils and defined it as a possible mirroring of the NETosis event within alveolars. Moreover, in their report, the abundant RNA burden in multinucleated cells that crowded the alveolar space was interpreted as a sign of cellular infection. On the other hand, cardiac biopsy samples showed a scattered myocyte necrosis without a specific viral induced lymphocytic infiltration [97]. Taken together, these studied are showing that as we are facing a multi-faced disease, to find a perfect therapy, COVID-19 must not be treated as a simple viral infection.

5. Immunological diagnosis

Before finding the best treatment, we must meet our urgent needs in estimating of disease severity and patient's possible outcome by finding the best prognostic and diagnostic index. As previously described the N8R ratio may be one of the possible efforts [41]. It has been shown that patients with COVID-19 often have lymphocytopenia with or without leukocyte abnormalities. According to this study the degree of lymphocytopenia provides a perspective toward disease prognosis due to its positive correlation with disease severity [98]. Based on clinical reports documented by Zhang et al. from 82 death cases with SARS-CoV-2, these patients had neutrophilia (74.3%), lymphopenia (89.2%) and thrombocytopenia (24.3%) upon admission. It has also been observed increased neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio of >5 (94.5%) and systemic immune-inflammation index of >500 (89.2%) with high level of IL-6, C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase in all cases they detected [99].

In another attempt, Maohua Li and colleagues generated COVID-19-specific polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies against different areas of COVID-19 Nucleoprotein (N) through immunization of animals with synthetic peptides. Characterized antibodies were used for serological diagnostic tools such as immunohistochemistry staining of tissue sections from SARS-CoV-2 infected patients and sandwich ELISA kit that could detect the concentration of virus or NP of COVID-19 in the vaccine preparations [100]. Hopefully, Hongye Wang et al. provided the SARS-CoV-2 proteome array to introduce commercial antibodies for SARS-CoV that can target SARS-CoV-2 proteins and are suitable for COVID-19 researches. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 immunogenic epitopes directed IgM and IgG were profiled in ten COVID-19 patients to be applied in diagnostic approaches [101].

More recently several tests have been developed in many laboratories. Amanat and co-workers developed sensitive and specific ELISA test based on the recombinant full-length S protein and receptor-binding domain (RBD) epitopes to detect and screen seroconversion just 3 days post COVID-19 symptom onset [102]. There was no cross-reactivity from other human coronaviruses in their study alongside strong reactivity for IgA, IgM and IgG3 probably due to the specificity of S1 antigen for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis [103] and highly number epitops found on S protein [102]. Therefore, the sensitivity of the epitopes on which test is performed may be a detemnied factor for the efficient detection of specific antibodies. For this reason, the sensitivity of two antigens, recombinant nucleocapsid protein (rN) and spike protein (rS), were compared by Liu et al. to detect specific antibodies in COVID-19 patients. Collected data revealed that the detection of rS-specific IgM was more sensitive in comparison to that of rN-spcific IgM, possibly due to the higher immunogenicity of the S protein than N protein [104].

Additional effort has been taken by Li and collaborations through developing a point-care lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) test based on the RBD antigen of the SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein with the ability of IgM and IgG detection simultaneously within 15 min and higher sensitivity than the individual IgG and IgM tests. Nonetheless the limitation of detection was not determined in the test [105].

6. Treatments

Until now there is no licensed specific anti COVID-19 treatment and the primary guidelines in the clinical management are on reducing clinical symptoms and supportive cares [[106], [107], [108], [109]]. There are a plenty of clinically classic under use therapies and a vast range of ongoing clinical trials under investigation that we will discuss here.

6.1. Classic therapies

Chloroquine and hydroxylChloroquine are possibly effective because they may have the ability to prevent releasing virus into cells through increasing endosomal PH and interfering virus-cell fusion. It also interferes with virus-receptor binding by blocking glycosylation of SARS-CoV cellular receptor, ACE2 [110]. They also show immunomodulating effect through down-regulation of inflammatory cytokine production. Based on some clinical trials conducted on chloroquine phosphate, it showed sufficient efficacy and safety in the therapeutic management of COVID-19 associated pneumonia [111]. Along with that, antiviral therapeutics including Lopinavir, Ritonavir and Remdesivir are effective by inhibiting different phases of virus life cycle [112,113].

As an adjunctive therapy azithromycin is applied for prevention of bacterial secondary infection. Tocilizumab in CSS cases used as it can put out the inflammation related fire by inhibiting IL-6 as a major driver of CSS [114]. These remedies are partially effective in disease control so we need better specific medications.

6.2. Novel therapies

Novel anti-COVID-19 therapies mainly focus on immunomodulation that targets different aspects of innate and adaptive immunity. At the front line, the most important interventions are virus-entry preventive agents, cytokine, chemokine and JAK-STAT inhibitors and blocking of immune-suppressive molecules [115].

Recently, Li et al. have introduced two potential drugs using a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network containing 125 hub genes of genes co-expressed with ACE2 for treatment of SARS-CoV-2 [116]. One of them is ikarugamycin discovered as an antibiotic however it is considered in term of an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis [117]. Regarding, it has been revealed that SARS-CoV gets into host cells through clathrin-mediated endocytosis so ikarugamycin may be a choice to treat COVID-19 as a result of similarity to SARS-CoV [118]. Another drug is molsidomine that is a long-acting vasodilator [119] and also a nitric oxide (NO) donor. Some literatures showed that inhalation of Nitric oxide (NO) can alleviate the sign of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in patients [120] and provide selective vasodilation of the pulmonary circulation to improve oxygenation in patients with SARS [121]. Furthermore, NO is able to block the replication cycle of SARS-CoV [122] hence molsidomine is suggested to alleviate the symptoms of COVID-19.

It is proved that IFN-I is produced upon intracellular pathogen invasion. Two important agents such as DNA sensor cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS) and its downstream molecule STING (stimulator of interferon genes, also known as ERIS/ MITA) control transcription of many inflammatory mediators, including type I and type III interferons [123,124]. Deng et al. revealed that regulating the upstream of the cytokines production may be a promising approach against COVID-19. According to the dysregulated IFN-I production in COVID-19, they supposed preventing aberrant activation of cGAS-STING pathway through their antagonistic drugs suramin and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitors respectively may be helpful in cytokine storm alleviating and treatment of severe lung infection induced by SARS-CoV-2. Given their studies, FDA approved drugs like suramin and ALK inhibitors could be worthful in clinical trials [22]. More recently, Chen et al. have reported a SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia successfully treated by thalidomide combined with low-dose glucocorticoid. Thalidomide is not only an immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory agent but also relieves anxiety to reduce oxygen consumption, lessen vomiting and also lung exudation probably by inhibiting the growth of new blood vessels [125].

Further strategy that can be considered for treatment of severe infected COVID-19 patients is passive immunotherapy using convalescent plasma (CP). There are a plenty of ongoing clinical trials for understanding the efficacy of CP therapy around the globe and some of them are summarized in Table 1 . Although FDA EU have announced some guidelines for this type of therapy, but the exact concentration and timing is still a matter of debate. In a general point of view, 200–500 ml of CP units mostly through 14 days of disease onset, were used in different studies [126]. Hence, it has also been reported that many recovered COVID-19 patients donated plasma to severe patients and showed primary favorable results. In convince with this study, it has been discovered that horse anti-SARS-CoV serum can surprisingly cross-neutralized SARS-CoV-2 infections [3]. So it can be an expected idea to imply passive immunity to COVID-19 through SARS antibodies. Shen et al. reported a CP for 5 severe ill patients from recovered cases. Four patients with no coexisting diseases received convalescent plasma at day 20 and a patient with mitral valve insufficiency and hypertension received the plasma transfusion at day 10 after admission. The results showed that the RNA of SARS-CoV-2 was negative between 1 and 12 days after transfusion in respiratory samples. Besides, the clinical symptoms of the cases reduced and their antibody titers raised in a time-dependent manner. The specific IgG and IgM titers increased from day 3 after transfusion and maintained a high level at day 7 post transfusion [127]. Although, the study has some limitations as there was no control group of patients without any interventions, administration of convalescent plasma, to compare outcomes since it is not possible to determine the true clinical effects of CP on patients. Moreover, patients received various other therapies which made difficult to distinguish the direct effect of the intervention [127].

Table 1.

A summary of ongoing classical therapies and vaccine platforms for COVID-19.

| Trial code | Intervention | Country | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04333550 | Daily IV deferoxamin for 3–5 days | Iran | I/II |

| NCT04333420 | Best supportive care+ IFX1 | Netherland | II/III |

| NCT04324996 | ACE-2CAR-NK/ NKG2D CARNK/ ACE2-NKG2D CAR NK/ NK /IL-15 NK injection (108 cells/kg/week) | China | I/II |

| NCT04304313 | Soldenafil citrate tablets | China | III |

| NCT04326920 | Sargramostim inhalation/IV injection | Belguim | IV |

| NCT04299724 | Pathogen specific COVID19/aAPC (5 × 106) vaccine three sub cutaneous injection | China | I |

| NCT04307693 | Lopinavir/ritonavir /Hydroxy chloroquine sulfate oral tablets (7–10 days) | China | II |

| NCT04292899 | Remdesvir IV injection | South Korea | III |

| NCT04276896 | LV-SMENP-DC (5 × 106) vaccine and antigen-specific CTLs (1 × 108)sub cutaneous injection | China | I/II |

| NCT04327206 | BCG vaccine | Australia | III |

| NCT0425484 | Abidol hydrochloride/ Interferon atomization | China | IV |

| NCT04263402 | Methylprednisolone <40 mg/d or 40-80 mg/d for 7 days (IV) | China | IV |

| NCT04315948 | Remdesivir/Lopinavir/ritonavir/ Interferon Beta-1A/Hydroxychloroquin | France | III |

| NCT04320238 | recombinant human interferon Alpha-1b drops/ thymosin alpha 1 SC injection | China | III |

| NCT03808922 | DAS181 4.5 mg | USA | III |

| NCT04330300 | Thiazide or Thiazide-like diuretic/ Calcium Channel Blockers / ACE inhibitor/ Angiotensin receptor blocker | Ireland | IV |

| NCT04283461 | mRNA-1273 vaccine | USA | I |

| NCT04405076 | mRNA-1273 (50-100μg) | USA | II |

| NCT04322682 | Colchicine 0.5 mg | Canada | III |

| NCT04252274 | Darunavir and Cobicistat | China | III |

| NCT04275245 | Meplazumab | China | I/II |

| NCT04341038 | Tacrolimus (8–10 ng/ml blood level)/ Methylprednisolone (120 mg/day) | Spain | III |

| NCT04374032 | metenkefalin + tridecactide | Bosnia and Herzegovina | II/III |

| NCT04393038 | ABX464 50 mg | France | II/III |

| NCT04335136 | RhACE2 (IV twice daily) | Austria, Denmark, Germany | II |

| NCT04380701 | BNT162a1/ BNT162b1/BNT162b2/ BNT162c2 (Anti-viral RNA vaccine), IM | Germany | II |

| NCT04388826 | Veru-111 (18 mg capsule orally) α and β tubulin inhibitor | USA | II |

| NCT04388826 | Camostat Mesilate (2 × 100 mg pills 3 times daily for 5 days) | Denmark | II |

| NCT04340557 | Losartan 12.5 mg orally twice daily for up to 10 days | USA | IV |

| NCT04334629 | Lipid Ibuprofen 200 mg | UK | IV |

I·V = intra venous, RhACE2 = Recombinant human angiotensin – converting enzyme 2, S·C = sub cutaneous.

In addition, developing human single-chain antibodies (HuscFvs) or humanized single-domain antibodies (sdAb, VH/VHH) which can pass through the membrane of virus-infected cells (transbodies) and interfere with biological features of virus replication may be another achievement. Thus, exploiting transbodies directed against coronavirus intracellular proteins like papain-like proteases (PLpro), cysteine-like protease (3CLpro) or other non-structural proteins (nsp) that are vital for virus replication and transcription, can be beneficial approach served as a safe and effective passive immunization for virus exposed individuals or therapeutic agent for infected patients [85]. Another effort was generating recombinant human monoclonal antibody (mAb) to neutralize SARS-CoV. CR3022 is a SARS-CoV specific human mAb which can bind RBD of SARS-CoV-2 and may be an effective therapeutics candidate to SARS-CoV-2 infections [128]. Other mAbs neutralizing SARS-CoV, such as m396 and CR3014 could be plausible for SARS-CoV-2 treatment [85,129]. It has been evaluated that m396 and CR3014 failed to bind the S protein of COVID-19 representing less similarities between receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in these cases [85].

Therapeutic agents such as specific antibodies or compounds which neutralize cytokines or their receptors like Adalimumab (TNF-α) and CMAB806 (IL-6) [22] could be valuable to alleviate host inflammatory responses especially those acting in the lung may improve immune-pathologic effects of COVID-19 [130]. Furthermore, an in vitro study indicated that anti-CD147 humanized antibody (Meplazumab) can notably neutralize virus and prevent it to infect host cells [7]. In addition, application of camostat mesylate as an inhibitor of TMPRSS2 activity should be considered in infected ones [6].

NET suppressing agents also have been suggested as probable therapies. Inhibitors of NET forming molecules such as Neutrophil elastase (NE), peptidyl arginine deiminase type 4 (PAD4) and gasdermin D across with mucosal NET digestion by DNase could become useful [43]. Global efforts for finding new remedies are still an active field and everyday new clinical trial are being registered that some of the important ones are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Covid19 Immunomodulatory ongoing therapies (clinical trial .gov).

| Type of immunomodulation | Trial code | Intervention | Country | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro -inflammatory cytokine inhibitors | NCT04317092 | Tocilizumab injection (8 mg/kg) | Italy | II |

| NCT04315298 | Sarilumab(IV) | USA | II/III | |

| NCT04339660 | Anakinra (200 mg/ 3 times per day for 1 week)/ Tocilizumab (8 mg/kg once)/ IV | Greece | I | |

| NCT04364009 | Anakinra (100 mg/6 h/ three days- 100 mg/12 h/ 6 days) IV injection for 10 days + oSOC vs oSOC only | France | III | |

| NCT04347226 | BMS-986253 (Anti-IL-8) 2400 mg IV | USA | II | |

| NCT04399980 | Mavrilimumab (Anti GM-CSF R α chain) | USA | II | |

| NCT04379076 | CYT107 (Anti IL-7) 10 μg/kg twice a week for two weeks -IM | UK | II | |

| NCT04363853 | Tocilizumab | Mexic | II | |

| NCT04335071 | Tocilizumab 8 mg/kg bodyweight, max. Single dose 800 mg | Switzerland | II | |

| NCT04351243 | Gimsilumab(anti GM-CSF)/IV | USA | II | |

| NCT04324021 | Emapalumab (anti-IFN-ϒ) / Anakinra | Sweden | II/III | |

| NCT04335305 | Pembrolizumab anti-PD-1)) (200 mg IV)/ Tocilizumab (800 mg IV) | Spain | II | |

| NCT04351152 | Lenzilumab (anti- GM-CSF) IV | USA | III | |

| NCT04320615 | Tocilizumab | Switzerland | III | |

| NCT04343989 | Clazakizumab (25and 12.5 mg) | USA | II | |

| NCT04377750 | Tocilizumab (800 mg) | Israel | IV | |

| NCT04330638 | Anakinra/ Siltuximab/Tocilizumab | Belguim | III | |

| NCT04380519 | Olokizumab 64 mg s.c 160 mg/ml | Russia | III | |

| JAk inhibitors | NCT04320277 | Baricitinib 4 mg/day/orally | Italy | III |

| NCT04373044 | Baricitinib / Hydroxychloroquine | USA | II | |

| NCT04338958 | Ruxolitinib | Germany | II | |

| NCT04377620 | Ruxolitinib | USA | III | |

| NCT04348695 | Ruxolitinib(5 mg)Simvastatin (40 mg/day) | Spain | II | |

| NCT04390464 | Ravulizumab (anti C5)/Baricitinib | UK | IV | |

| Convalscent Plasma (CP)therapy | NCT04385043 | Hyperimmune plasma vs standard therapy | Italy | II/III |

| NCT04384497 | Daily 200 ml of CP infusion | Sweden | I/II | |

| NCT04364737 | 250-500 ml CP infuson | USA | II | |

| NCT04392414 | 300 ml CP infusion | Russia | II | |

| NCT04345991 | 200–220 ml CP infusion | France | II | |

| NCT04342182 | 300 ml CP infusion | Netherland | II/III | |

| NCT04358783 | 200 ml CP infusion | Mexico | II | |

| NCT04403477 | 200 ml CP infusion | Bangladesh | II | |

| NCT04348656 | 250–500 ml CP infusion | Canada | III | |

| Cell therapy | NCT04288102 | MSC IV inejection | China | I/II |

| NCT04313322 | WJ-MSC (1 × 06) IV injection 3 times by 3 days intervals | Jordan | I | |

| NCT04269525 | UC-MSCs IV injection | China | II | |

| NCT04339660 | 1 × 106 UC-MSCs /kg body weight | China | II | |

| NCT04288102 | 3times of 4 × 107 MSCs by three days intervals | China | II | |

| NCT04366063 | MSC ± EVs | Iran | II/III | |

| NCT04333368 | UC-MSC 1 × 106/kg IV | France | II | |

| NCT04331613 | CAStem IV 3-10 × 106 cells/kg | China | II | |

| NCT04355728 | 100 × 106 UC-MSC cells IV injection | USA | II | |

| Others | NCT04280588 | Fingolimod 0.5 mg orally once a day for 3 days | China | |

| NCT04317040 | CD24Fc | USA | III | |

| NCT04263402 | Methylprednisolone <40 mg/d or 40-80 mg/d for 7 days (IV) | China | IV | |

| NCT04334460 | BLD-2660 (small molecule as Calpain inhibitor) orall | USA | II | |

| NCT04275245 | Meplazumab(10 mg IV, every day for 2 days) | China | II | |

| NCT04371367 | iv administration of avdoralimab (anti C5aR) | France | II | |

| NCT04347239 | Leronlimab (700 mg/week) SC | USA | II | |

| NCT04275414 | Bevacizumab 500 mg | Italy/China | II/III |

I.V. = Intravenous, s.c. = Sub cutaneous, I.M = Intra muscular, oSOC = optimized Standard of care, MSC = Mesenchymal stem cell, UC-MSC = Umbilical cord-MSC, WJ-MSC = Warton Jelly MSC, CAStem = immunity- and matrix-regulatory cells (IMRCs) also named M cells, differentiated from clinical-grade human embryonic stem cells (hESCs).

7. Vaccines

Taisheng and co-workers have showed that SARS-CoV specific humoral and cellular immune responses against a pool of predicted highly antigenic peptides derived from different parts of virus structure was detectable even 2 years after recovery in infected cases. However, during their follow up unfortunately the absolute lymphocyte count did not rise to the normal level. So they suggested that immune system impaired permanently or its recovering process is time-consuming [131]. In consistence with this study, Yee-Joo et al. have been shown that the memory CD8+T cells of SARS infected cases could detect the virus structural proteins even 11 years after disease [132]. Counting on these studies and high resemblance of SARS-CoV-2 to SARS-CoV in different aspects draws a hopeful landscape for COVID-19 vaccine production.

Ahmed et al. determined a set of B cell and T cell epitopes derived from the spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins of COVID-19. Proposed T cell epitopes has been also estimated to be presented by broad ranges of MHC alleles so they can trigger protective response among the globe. Since these epitopes had no mutation, it has been suggested that the identified epitopes could act as potential immune targets in COVID-19 vaccination strategies [133].

It is considered that S protein as an important vital immune-dominant protein of coronaviruses [134] is able to induce protective immunity against SARS-CoV through involving T-cell responses and neutralizing-antibody production [64]. Recent findings demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 S2 subunit of S protein has a critical role in virus fusion and its entrance into host cells. In S2 subunit the heptad repeat 1 (HR1) and heptad repeat 2 (HR2) are two important domains that interact and form a construction facilitating in virus fusion. Based on sequence alignment studies, S2 subunit is highly conserved between SARS-CoV and COVID-19 with 92.6% and 100% homology for HR1 and HR2 domain respectively [135]. So these domain could consider as important targets to be blocked and thereby prevented viral entry and infection [129].

As it is known CD8+T cells are the most prominent populations associated to protection against COVID-19 [32]. Herst CV et al. proposed that a COVID-19 peptide vaccine designed to activate specific CD8+T cells based on the specific epitopes targeted by survivors of documented SARS-CoV-2 infection could be successfully preventative just like for Ebola outbreak [136]. Adding to this in a most recent study, the comparison of T cell subsets between recovered COVID-19 cases and healthy individuals revealed an interesting pattern of immunodominancy. It has been shown that the virus spike protein which is mainly used for vaccine production can only elicit a small population of responsive CD8+T cells. Therefore, an effective vaccine needs other antigens such as derivatives of M, nsp6, ORF3a /N viral particle. Besides, surprisingly, in this study, the writers reported that 40–60% of unexposed cases showed CD4+ responses against SARS-CoV-2 which were made by Th1 group. They brought up the importance of considering the pre-existence of cross-reactive immunity toward SARS-CoV-2 infection in vaccine development which might be the result of exposing to common cold coronaviruses. According to H1N1 Flu experience, this pre-formed immune response was correlated with less severity. Thus, this effect might be the incidence of milder response in some of the infected ones as their study population was from non-hospitalized patients and in vaccine production these specific analysis seems to be an obligation [137].

However, due to consideration ethics issues, biosafety and technical limitations, most of the current attempts were taken from animal model studies and not directly from human subjects. More investigations using patient samples are needed to develop promising strategies in vaccination. Nonetheless, generating an effective vaccine and antiviral drug is a priority to control the outbreak of COVID-19 infection. There are different clinical trials across the world for finding an effective vaccine or anti-viral therapy which is summarized in table2.

8. Conclusion

In general point of view, SARS-CoV-2 stimulates almost every aspect of the immune compartment that leads to madness of immune response. Although, a short period of time has passed since the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2, researchers have learned a lot but there are many aspects of COVID-19 immunologic response which are still hidden for us. The most important question that needs to be answered is the logic of differences in susceptibility to this virus. By finding accurate prognosis factor and enhancing diagnosis methods, we can decrease the number of deaths. Hopefully the first steps for COVID-19 treatment and vaccine designating has been taken. Certainly this virus needs both antiviral and immune-modulatory/regulatory treatments together to become under control.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Zhu N., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu A., et al. Genome composition and divergence of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) originating in China. Cell Host Microbe. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou P., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan Y., et al. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J. Virol. 2020;94(7) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tipnis S.R., et al. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(43):33238–33243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K., et al. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 Invades Host Cells Via a Novel Route: CD147-spike Protein. BioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui J., et al. N-glycosylation by N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V enhances the interaction of CD147/basigin with integrin β1 and promotes HCC metastasis. J. Pathol. 2018;245(1):41–52. doi: 10.1002/path.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosugi T., et al. CD147 (EMMPRIN/Basigin) in kidney diseases: from an inflammation and immune system viewpoint. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015;30(7):1097–1103. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su H., Yang Y. The roles of CyPA and CD147 in cardiac remodelling. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2018;104(3):222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guan W.-j., et al. 2020. Clinical Characteristics of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Infection in China. MedRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan J.F.-W., et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang C., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z., et al. Recovery from severe H7N9 disease is associated with diverse response mechanisms dominated by CD8+ T cells. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6833. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M., et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Wit E., et al. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14(8):523. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang C., et al. The cytokine release syndrome (CRS) of severe COVID-19 and Interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R) antagonist Tocilizumab may be the key to reduce the mortality. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020:105954. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Channappanavar R., Perlman S. Seminars in Immunopathology. Springer; 2017. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kindler E., Thiel V., Weber F. Interaction of SARS and MERS coronaviruses with the antiviral interferon response. Adv. Virus Res. 2016:219–243. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.006. Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evren E., Ringqvist E., Willinger T. Origin and ontogeny of lung macrophages: from mice to humans. Immunology. 2019 doi: 10.1111/imm.13154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng X., Yu X., Pei J. 2020. Regulation of Interferon Production as a Potential Strategy for COVID-19 Treatment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.00751. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziegler C.G., et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanco-Melo D., et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang C., et al. 2020. Aveolar Macrophage Activation and Cytokine Storm in the Pathogenesis of Severe COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y., et al. 2020. Aberrant Pathogenic GM-CSF+ T Cells and Inflammatory CD14+ CD16+ Monocytes in Severe Pulmonary Syndrome Patients of a New Coronavirus. bioRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang D., et al. 2020. COVID-19 Infection Induces Readily Detectable Morphological and Inflammation-related Phenotypic Changes in Peripheral Blood Monocytes, the Severity of Which Correlate With Patient Outcome. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussell T., Bell T.J. Alveolar macrophages: plasticity in a tissue-specific context. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14(2):81–93. doi: 10.1038/nri3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramachandran P., et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature. 2019;575(7783):512–518. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1631-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabrera-Benitez N.E., et al. Mechanical ventilation–associated lung fibrosis in acute respiratory distress SyndromeA significant contributor to poor outcome. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2014;121(1):189–198. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reyfman P.A., et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of human lung provides insights into the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019;199(12):1517–1536. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2410OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao M., et al. 2020. The Landscape of Lung Bronchoalveolar Immune Cells in COVID-19 Revealed by Single-cell RNA Sequencing. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider C., et al. Induction of the nuclear receptor PPAR-γ by the cytokine GM-CSF is critical for the differentiation of fetal monocytes into alveolar macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15(11):1026–1037. doi: 10.1038/ni.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chuquimia O.D., et al. Alveolar epithelial cells are critical in protection of the respiratory tract by secretion of factors able to modulate the activity of pulmonary macrophages and directly control bacterial growth. Infect. Immun. 2013;81(1):381–389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00950-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pechkovsky D.V., et al. CCR2 and CXCR3 agonistic chemokines are differently expressed and regulated in human alveolar epithelial cells type II. Respir. Res. 2005;6(1):75. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thorley A.J., et al. Innate immune responses to bacterial ligands in the peripheral human lung–role of alveolar epithelial TLR expression and signalling. PLoS One. 2011;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silveyra P., et al. Knockdown of Drosha in human alveolar type II cells alters expression of SP-A in culture: a pilot study. Exp. Lung Res. 2014;40(7):354–366. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2014.929757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian Z., et al. Innate immune response of human alveolar type ii cells infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013;48(6):742–748. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0339OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Z., et al. 2020. Clinical and Laboratory Profiles of 75 Hospitalized Patients With Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Hefei, China. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Y., et al. 2020. Exuberant Elevation of IP-10, MCP-3 and IL-1ra During SARS-CoV-2 Infection is Associated With Disease Severity and Fatal Outcome. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J., et al. 2020. Longitudinal Characteristics of Lymphocyte Responses and Cytokine Profiles in the Peripheral Blood of SARS-CoV-2 Infected Patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J., et al. 2020. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte Ratio Predicts Severe Illness Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the Early Stage. MedRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnes B.J., et al. Targeting potential drivers of COVID-19: neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Exp. Med. 2020;(6):217. doi: 10.1084/jem.20200652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zuo Y., et al. 2020. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) as Markers of Disease Severity in COVID-19. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan L., et al. Lymphopenia predicts disease severity of COVID-19: a descriptive and predictive study. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2020;5(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0148-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu X., et al. Exploration of panviral proteome: high-throughput cloning and functional implications in virus-host interactions. Theranostics. 2014;4(8):808. doi: 10.7150/thno.8255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu H., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome diagnostics using a coronavirus protein microarray. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103(11):4011–4016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510921103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zou L., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qing E., Gallagher T. SARS coronavirus Redux. Trends Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao A.T., Gao C., Zhang S. Profile of specific antibodies to SARS-CoV-2: the first report. The Journal of infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo L., et al. Profiling early humoral response to diagnose novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao J., et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takada A., Kawaoka Y. Antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infection: molecular mechanisms and in vivo implications. Rev. Med. Virol. 2003;13(6):387–398. doi: 10.1002/rmv.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tetro J.A. Is COVID-19 receiving ADE from other coronaviruses? Microbes Infect. 2020;22(2):72–73. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tirado S.M.C., Yoon K.-J. Antibody-dependent enhancement of virus infection and disease. Viral Immunol. 2003;16(1):69–86. doi: 10.1089/088282403763635465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dejnirattisai W., et al. Enhancing cross-reactive anti-prM dominates the human antibody response in dengue infection. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2010;(5979):328. doi: 10.1126/science.1185181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guzman M.G., et al. Neutralizing antibodies after infection with dengue 1 virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13(2):282. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katzelnick L.C., et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of severe dengue disease in humans. Science. 2017;358(6365):929–932. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pichler K., Schneider G., Grassmann R. MicroRNA miR-146a and further oncogenesis-related cellular microRNAs are dysregulated in HTLV-1-transformed T lymphocytes. Retrovirology. 2008;5(1):100. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Channappanavar R., et al. Dysregulated type I interferon and inflammatory monocyte-macrophage responses cause lethal pneumonia in SARS-CoV-infected mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(2):181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshikawa T., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus-induced lung epithelial cytokines exacerbate SARS pathogenesis by modulating intrinsic functions of monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2009;83(7):3039–3048. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01792-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Donnelly C.A., et al. Epidemiological and genetic analysis of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004;4(11):672–683. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu L., et al. Anti–spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI insight. 2019;4(4) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Du L., et al. The spike protein of SARS-CoV—a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7(3):226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang Z.-y., et al. Evasion of antibody neutralization in emerging severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102(3):797–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409065102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang Y., et al. Bcl-xL inhibits T-cell apoptosis induced by expression of SARS coronavirus E protein in the absence of growth factors. Biochem. J. 2005;392(1):135–143. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen G., et al. 2020. Clinical and Immunologic Features in Severe and Moderate Forms of Coronavirus Disease 2019. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou Y., et al. Pathogenic T cells and inflammatory monocytes incite inflammatory storm in severe COVID-19 patients. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu Z., et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8(4):420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen J., et al. Cellular immune responses to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection in senescent BALB/c mice: CD4+ T cells are important in control of SARS-CoV infection. J. Virol. 2010;84(3):1289–1301. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01281-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao J., et al. Clinical pathology and pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Zhonghua shi yan he lin chuang bing du xue za zhi= Zhonghua shiyan he linchuang bingduxue zazhi= Chinese journal of experimental and clinical virology. 2003;17(3):217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao J., et al. Age-related increases in PGD 2 expression impair respiratory DC migration, resulting in diminished T cell responses upon respiratory virus infection in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121(12):4921–4930. doi: 10.1172/JCI59777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao J., et al. Evasion by stealth: inefficient immune activation underlies poor T cell response and severe disease in SARS-CoV-infected mice. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fast E., Chen B. 2020. Potential T-cell and B-cell Epitopes of 2019-nCoV. bioRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Diao B., et al. 2020. Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Medrxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li X., et al. Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]