Abstract

Objective:

Both caregivers and the older adults they care for can experience declines in quality of life (QOL) over the course of the dementia trajectory. Little research has examined QOL in African-American caregivers and even less in African-American persons with dementia (PWDs), making it difficult to identify associated factors.

Method:

Guided by the Negro Family as a Social System framework, a secondary data analysis was used to examine the influence of family structure, instrumental and expressive role functions on QOL in a sample of 62 African-American dementia dyads (i.e. African-American PWDs and their African-American caregivers). Dyadic data were analyzed using multilevel modeling to control for the interdependent nature of the data.

Results:

On average, African-American PWDs reported significantly worse QOL than African-American caregivers. Within African-American dementia dyads, QOL covaried. African-American PWDs experienced significantly worse QOL when their caregiver was a non-spouse and they themselves perceived less involvement in decision-making. In addition, African-American caregivers experienced significantly worse QOL when they reported greater dyadic strain with the African-American PWD and were non-spouses of African-American PWDs.

Conclusion:

Findings suggest understanding the interpersonal characteristics (e.g., dyadic relationship, family structure and role functions) of dyads may hold promise for improving their QOL.

Keywords: Multilevel modeling, caregiver, decision-making involvement, dyadic strain

The population of African-American older adults in the United States is continuing to increase, with an estimated increase from 3.8 million in 2012 to 10.3 million by the year 2050 (Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014). In addition to the increased number of African-American older adults, research suggests an increased incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in African-American older adults compared to non-Hispanic White and Hispanic older adults (Alzheimer’s Association, 2018). This incidence is associated with greater rates of diabetes, hypertension and stroke in the African-American population (Alzheimer’s Association, 2018). Despite the suggested risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias in African-American older adults, limited research exists that examines the African-American person with dementia (PWD) and even less research that investigates both African-American PWDs and their African-American caregivers. Research has well-established that PWDs can provide their own responses to health assessments (Brod, Stewart, Sands, & Walton, 1999), consistently and reliably over time (Clark, Tucke, & Whitlatch, 2008). In addition, the inclusion of African-American PWDs in research aligns with African-American culture.

Decision-making involvement and quality of life (QOL)

Caregiving is an inherently dyadic process that involves the interactions and relationship of both the PWD and their caregiver (Lyons, Zarit, Sayer, & Whitlatch, 2002; Martire, Schulz, Helgeson, Small, & Saghafi, 2010). Caregiving consists of multiple decisions made throughout the day, often by PWDs or on their behalf. Research that includes the PWD and their caregiver provides insight on how dyads (i.e. PWDs and caregivers) function during caregiving (Coeling, Biordi, & Theis, 2003; Lyons & Lee, 2018; Menne, Tucke, Whitlatch, & Feinberg, 2008; Miller, Lee, Whitlatch, & Lyons, 2018; Miller, Whitlatch, & Lyons, 2016). Research highlighted that decision-making involvement (e.g. verbal and/or non-verbal communication) could be shared between both members of dementia dyads (Menne et al., 2008). When PWDs perceived greater decision-making involvement, both members of dyads experienced significantly better QOL (Menne et al., 2008). On the other hand, negative experiences in caregiving such as increased dyadic relationship strain have been associated with less decision-making involvement by PWDs (Miller, Lee, et al., 2018). Research has also found adverse effects of the caregiving process on caregivers’ QOL (Schulz & Beach, 1999; Schulz & Martire, 2004). Yet, to our knowledge no study has examined decision-making involvement of PWDs in a sample of entirely African-American dementia dyads.

QOL in African-American dementia dyads

The majority of QOL research has included only small numbers of African-American caregivers (if any), limiting generalizability to African-American dementia dyads. Studies that have examined African-American caregivers have found that these caregivers reported less psychological distress (Dilworth-Anderson & Gibson, 2002) and greater positive aspects from caregiving (Haley et al., 2004) when compared with non-Hispanic White caregivers. African-American PWDs have been studied far less, resulting in a scarcity of research focused on QOL of African-American PWDs. Menne, Judge, and Whitlatch (2009) noted one factor that was associated with worse QOL of PWDs was being African-American. In this study, African-American PWDs were compared to non-Hispanic White PWDs with little consideration to the cultural differences within and among these two racial groups. Given both the paucity of research and conceptual frameworks focused on African-American dementia dyads, there is a strong need to examine and understand dyads through a more culturally relevant theoretical lens.

Proposed conceptual framework

The Negro Family as a Social System is a conceptual framework originally proposed by Dr. Andrew Billingsley in 1968 and later reprinted in 1988. The Negro Family as a Social System consists of a network of three social systems—the Negro family, the Negro community and the Wider society (Billingsley, 1968). Centrally located in the original model is the Negro family, highlighting the importance of dyadic relationships such as mother-daughter, father-son or mother-father.

Components of the Negro family include family structure and two role functions. Family structure is described based on the family composition (e.g. two-parent, single-parent or blended families) (Billingsley, 1968). In this study, family structure is adapted to describe the type of caregiver (i.e. spouse vs. non-spouse) of African-American dementia dyads. The two role functions are instrumental and expressive (Billingsley, 1968; Walsh, 2003). Instrumental role functions are characterized by maintaining the physical and social integrity of the family unit including decision-making (e.g. decision-making involvement of PWD), educational obtainment (e.g. educational level of caregiver), economic provision and maintaining health (e.g. cognitive status of PWD) (Billingsley, 1968; Walsh, 2003). Expressive role functions are characterized as maintaining social and emotional relationships among the family unit including positive and negative feelings (e.g. dyadic relationship quality), self-worth and belonging (Billingsley, 1968; Walsh, 2003). The Negro community, which should be viewed as a racial subsociety consisting of the dual nature of the African-American population—a group of people often characterized as monolithic but with great variability in conditions, personality and behaviors (Billingsley, 1968). The Negro community includes geographic regions, social class as well as businesses such as local barbershops or beauty salons. The Wider society consists of the health care, educational and political system, for example (Billingsley, 1968).

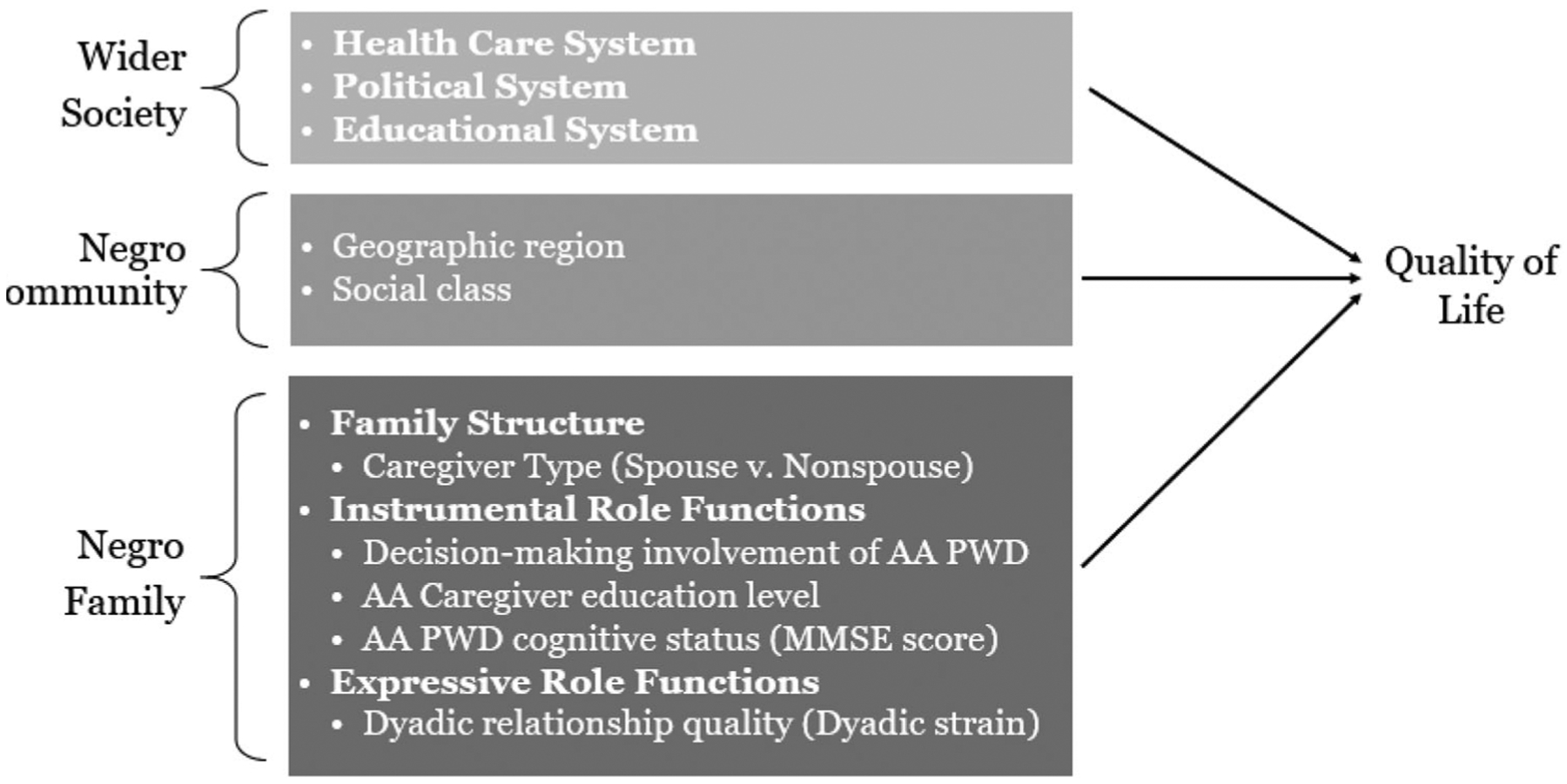

The model proposes that African-American families are embedded in a network of larger social systems (i.e. Negro community and Wider society) that influence outcomes of these African-American family members (Billingsley, 1968, 1992). QOL is an important outcome to consider. QOL can be defined as health related or a broader description encompassing mental, physical, social functions and health perceptions (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). Lawton (1991), further, described QOL as a multidimensional concept, which incorporates four main sectors—behavioral competence (e.g. activities of daily living and cognition), perceived QOL (e.g. relationships and health), objective environment (e.g. neighborhood and social networks) and psychosocial well-being (e.g. mental health and positive and negative emotions). Similarly, the tenets of The Negro Family as a Social System, reinforce this multidimensional concept of Lawton’s QOL by examining family structure (e.g. objective environment) and role functions (e.g. behavioral competence and psychosocial well-being). In addition, research supports the examination of family structure and instrumental role functions as predictors of QOL (Burgener & Twigg, 2002; Farina et al., 2017). Therefore, given the research supporting both the global nature of QOL and associated predictors of QOL, the examination of African-American dementia dyads should take into consideration some, if not all, of these broader influences. For example, African-American families have not had equal access to health care and education when compared to other ethnic and/or racial groups (Billingsley, 1968; Institute of Medicine, 2003). Thus, the health and well-being of African-American families could be negatively affected by the disproportionate access and not only being African-American. As a result, examining the QOL of African-American dementia dyads allows for recognition of the variability across dyads. Family structure, instrumental and expressive role functions were examined in this current paper as predictors of QOL of African-American dementia dyads (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed model from the Negro Family as a Social System (Billingsley, 1968). Each bracket on the left represents a network of interdependent relationships. The rectangles list the subsystems represented in each relationship (bolded text) and how these subsystems were operationalized as study variables. The arrows represent the proposed relationships between the network of relationships and subsystems associated with QOL. AA = African American PWD = person with dementia.

The current study is the first known study to examine family structure and role functions associated with QOL of both members of African-American dementia dyads. Using the Negro Family as a Social System, our research questions are: (1) Will there be a covariation between QOL of African-American PWDs and their African-American caregivers? and (2) Are family structure types of caregivers and instrumental and expressive role functions associated with QOL of African-American dementia dyads?

Method

Participants and procedures

The study is a secondary analysis of data collected between 1998 and 2004 as part of a longitudinal study examining the caregiving process of both PWDs and their family caregivers (Powers & Whitlatch, 2016). In the original study, inclusion criteria consisted of the following: (1) PWDs had a confirmed diagnosis of dementia (coded as yes/no) or a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score between 13 and 26, (2) PWD was community-dwelling and (3) PWD had a primary, informal family caregiver—person who provided the most caregiving (Powers & Whitlatch, 2016). In total, 202 community dwelling PWDs and their caregivers (131 non-Hispanic White dyads and 71 African-American dyads) were recruited from Cleveland, OH and San Francisco Bay area, CA. Cleveland area dyads were recruited from the Eldercare Services Institute of the Benjamin Rose Institute on Aging, and the former University Memory and Aging Center. San Francisco area dyads were recruited from Family Caregiver Alliance. For the current study, both members of the dyad were required to be African-American and have complete data on study predictors (i.e. type of caregiver, decision-making involvement, caregiver’s educational level, PWD’s cognitive status and dyadic relationship quality) and outcome variable (i.e. QOL). This resulted in a sample of 62 dyads, which is similar to other samples (Lyons et al., 2002; Miller, Lee, et al., 2018). Staff at these organizations reviewed their client lists to identify appropriate participants. Potential participants were then contacted via mail and screened for eligibility by telephone. Research staff then contacted the person with cognitive impairment if their caregiver had agreed to participate in the study. For the original study, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical approval for the current secondary analysis of de-identified data was obtained by the IRB at Oregon Health & Science University after being determined exempt from human subject review. Additional recruitment information is provided elsewhere (Feinberg & Whitlatch, 2001).

Outcome measure

QOL of the PWD and their caregiver was measured using equivalent versions of the Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease measure (QOL-AD) (Logsdon, Gibbons, McCurry, & Teri, 1999; Logsdon, Gibbons, McCurry, & Teri, 2002). The QOL-AD was created based on Lawton’s conceptual domains of QOL (Logsdon et al., 2002). The QOL-AD was developed to examine QOL in persons with mild-to-moderate dementia symptoms and has been used in previous studies to rate the QOL of both the PWD and their caregiver (Logsdon et al., 1999; Moon, Townsend, Whitlatch, & Dilworth-Anderson, 2017). The scale consists of 13 items (Logsdon et al., 2002); the reliability in this study was Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82 for African-American PWDs and Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89 for their caregivers. An example of the items on the scale is: ‘When you think about your whole life, and all the different things about you, would you say it’s ….?’ (Logsdon et al., 2002). Each item was rated by African-American PWDs and their caregivers based on their perceptions of different aspects of their own lives on a 4-point Likert scale: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good and 4 = excellent. Items are summed to a total score ranging from 12 to 48, with higher scores indicating better QOL.

Predictors

Family structure

Family structure of African-American dementia dyads was identified based on the type of caregiver of each dyad. The type of caregiver was reported by the caregiver and coded as spouse or non-spouse caregiver. Type of caregiver of the African-American dementia dyads was examined as a predictor of QOL.

Instrumental role functions

Decision-making involvement by African-American PWDs was examined using the Decision-Making Involvement Scale (DMI) (Menne et al., 2008), which has been used in previous studies to examine the perceived decision-making involvement of PWDs (Menne et al., 2008; Miller, Lee, et al., 2018). The DMI was created to allow PWDs to report on their perceived decision-making regarding day-to-day decisions supporting autonomy and independence of the PWD (Menne et al., 2008). The DMI is a 15-item scale (Menne et al., 2008), and the reliability in this study was Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86. A sample item from the scale is ‘How involved are you in decisions about what to do in your spare time?’ (Menne et al., 2008). Responses are answered based on a 4-point scale of 0 = not at all involved, 1 = a little involved, 2 = fairly involved and 3 = very involved. The total score is a mean of the scale, ranging from 0 to 3; higher scores indicate greater perception of decision-making involvement by African-American PWDs.

Other instrumental role functions included in the model were the educational level of African-American caregivers and cognitive status of African-American PWDs. The educational level of African-American caregivers reported by the caregiver was a proxy for socioeconomic status (Galobardes, Shaw, Lawlor, Lynch, & Davey Smith, 2006). In addition to using the MMSE as a screening tool, we used it to reflect the cognitive status of African-American PWDs. The MMSE is an 11-item scale (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975); the reliability of the MMSE in our study was Cronbach’s alpha = 0.54. The MMSE ranges from 0 to 30 with higher scores indicating better cognitive status (Folstein et al., 1975).

Expressive role function

The dyadic relationship quality was examined by the Dyadic Strain subscale of the Dyadic Relationship Scale (DRS) (Sebern & Whitlatch, 2007). The Dyadic Strain subscale was included in the analysis to examine dyadic relationship quality based on the perceived strain in the relationship reported by the African-American PWD and their caregiver (Menne et al., 2009; Miller, Whitlatch, Lee, & Lyons, 2018). The Dyadic Strain subscale is a 4-item measure for PWDs and a 5-item measure for caregivers; with a reliability of Cronbach’s alpha = 0.70 for African-American PWDs and Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77 for African-American caregivers in this study. A sample question: ‘Because of my health, I felt resentful toward my caregiver’ (PWD version) or ‘Because of helping my relative, I felt resentful toward him/her’ (caregiver version). A 4-point option response includes: 0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = agree and 3 = strongly agree. The total score is a mean of the scale ranging from 0 to 3; higher scores indicate greater perceived relationship strain.

Analysis plan

Multilevel modeling was used to analyze data at the level of the dyads while controlling for the interdependence in the data (Lyons et al., 2002; Sayer & Klute, 2005). The multivariate outcomes model simultaneously estimates the latent scores for both the African-American PWD and the African-American caregiver. The multilevel models were tested using Hierarchical Linear Modeling software, version 7.03 (Raudenbush et al., 2017). Predictors (type of caregiver, decision-making involvement of African-American PWDs, educational level of African-American caregivers, cognitive status of African-American PWDs, dyadic strain by African-American PWDs and their African-American caregivers) were added to a conditional Level 2 model (between-dyad) to determine their association with QOL. The first model or Level 1 unconditional model (i.e. no predictors) examines QOL of the African-American dementia dyad. The Level 1 unconditional model (within-dyad) represents the QOL score (Y) for both the African-American PWD and the African-American caregiver, the sum of a latent true score (β1 for the PWD and β2 for the caregiver), plus r, a residual term, that denotes measurement error. The equation is specified as follows:

where Yij depicts the QOL score i in dementia dyad j.PERSON WITH DEMENTIA is a dummy variable or indicator variable with a value of 1 if the response was obtained by the African-American PWD and a value of 0 if it was obtained by the African-American caregiver. CAREGIVER is a dummy variable or indicator variable taking on the value of 1 if the response is obtained by the African-American caregiver and a value of 0 if by the African-American PWD. The β1j and β2j depict the PWD’s and caregiver’s latent QOL scores, respectively. In addition, the Level 1 unconditional model provides a tau correlation, capturing the covariation of QOL of the African-American PWDs and their caregivers.

The Level 2 model (between-dyad) comprises simultaneous regression equations with β1j and β2j operating as dependent variables. The model can be specified as the following:

with γ10 and γ20 as the Level 2 intercepts, depicting average values of QOL for the African-American PWD and African-American caregiver, respectively, adjusting for the predictors in each equation. This model included family structure (i.e. type of caregiver), instrumental role functions (i.e. decision-making involvement of the African-American PWD, African-American caregivers’ educational level, African-American PWDs’ cognitive status) and expressive role functions (i.e. dyadic strain of African-American PWDs and their African-American caregivers) as predictors of QOL for both members of the African-American dementia dyad.

Parallel scales

To provide adequate information to estimate measurement error variances for both the African-American PWD and the African-American caregiver, parallel scales of the outcome measure QOL-AD were created for both members of the dyad (Barnett, Marshall, Raudenbush, & Brennan, 1993; Miller, Lee, et al., 2018; Sayer & Klute, 2005). Items from the QOL-AD were matched into pairs based on the closeness of their standard deviations to create six pairs with one item from each pair assigned to one of the two scales (for a total of 12 items). As a result, the process yielded two scales with equal variance and reliability for each member of the dyad (i.e. a total of four scores for each dyad).

Results

Sample characteristics

Background characteristics are provided in Table 1 for the 62 African-American dementia dyads. The majority of PWDs and their caregivers were female (PWD = 68%, caregiver = 81%). Most caregivers had attended high school or more (56%). African-American PWDs had a MMSE score of 21.08 (SD ± 3.94) and the majority (76%) had a diagnosis of dementia from a health care provider. On average, African-American PWDs perceived their decision-making involvement as ‘fairly involved’ (on a range of ‘not at all involved’ to ‘very involved’). Overall, African-American caregivers when compared to African-American PWDs were significantly younger, t(59) = 9.50, p < .001), predominantly daughters/daughters-in-law and had significantly better QOL, t(60) = −3.11, p < .01). Additionally, there was a large effect size for ages of African-American PWDs compared to their caregivers (d = 1.52) and a medium effect for African-American caregivers’ QOL compared to QOL of African-American PWDs (d = .50). There was no significant difference between African-American PWDs and their caregivers in perceived dyadic relationship strain but there was a small-medium effect size.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and measure descriptives (N = 62 dyads).

| AA PWD | AA CG | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, (mean ± SD) | 76.55 ± 7.84 | 60.49 ± 13.35*** | 1.52 |

| Women (%) | 42 (68%) | 50 (81%) | ——— |

| Spouse CG (%) | ——— | 19 (30.6%) | ——— |

| Non-spouse CG Daughter/daughter-in-law (%) | ——— | 27 (43.5%) | |

| Son/son-in-law (%) | ——— | 5 (8.1%) | ——— |

| Other relativea (%) | ——— | 11 (17.7%) | ——— |

| PWD lives with CG or someone else (%) | 24 (39%) | ——— | ——— |

| Years of care (in months), (mean ± SD) | ——— | 39.07 ± 39.38 | ——— |

| Greater than high school (%) | 29 (47%) | 35 (56%) | ——— |

| Dementia diagnosis by provider (%) | 47 (76%) | ——— | ——— |

| MMSE score, (mean ± SD) | 21.08 ± 3.94 | ——— | ——— |

| Dyadic strain, (mean ± SD) | 0.84 ± 0.57 | 1.01 ± 0.47 | 0.32 |

| Decision-making involvement, (mean ± SD) | 2.27 ± 0.66 | ——— | ——— |

| Quality of life, (mean ± SD) | 31.5 ± 5.49 | 34.39 ± 5.95** | 0.50 |

Notes: AA = African American; PWD = person with dementia; CG = caregiver; SD = standard deviation; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination. Effect size = Cohen’s d (difference between two means) = 0.20 (small), 0.50 (medium), 0.80 (large).

Other relatives (e.g. aunt/uncle, cousin, grandchild).

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001, significant difference between two groups.

Quality of life

Results of the unconditional (within-dyad) model (Table 2) show that PWDs and their caregivers reported moderate QOL. African-American caregivers reported significantly better QOL than African-American PWDs. Moreover, QOL within dyads covaried (tau correlation = 0.26), responding to our first research question and reinforcing the use of multilevel modeling. In addition, there was significant variability around the average scores of both African-American PWDs (χ2 = 287.14, p < .001) and caregivers (χ2 = 331.73, p < .001), indicating significant heterogeneity in QOL across dyads.

Table 2.

Multilevel models predicting African-American persons with dementia and their caregivers quality of life (N = 62 dyads).

| AA PWD | AA caregiver | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | t | Effect size (r) | β (SE) | t | Effect size (r) | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||

| Unconditional Model | ||||||

| Intercept | 31.5 (0.69)*** | 45.54 | 34.39 (0.75)*** | 45.54 | ||

| Conditional Model | ||||||

| Intercept | 29.37 (0.96)*** | 30.50 | 33.02 (1.09)*** | 30.31 | ||

| PWD MMSE score | −0.02 (0.17) | −0.14 | .00 | −0.17 (0.19) | −0.92 | .02 |

| PWD decision-making involvement | 2.72 (0.95)** | 2.85 | .36 | 0.95 (1.06) | 0.89 | .12 |

| Caregiver educational status | 0.93 (1.17) | 0.80 | .01 | 1.00 (1.34) | 0.75 | .01 |

| Caregiver dyadic strain | −1.24 (1.23) | −1.01 | .13 | −6.19 (1.39)*** | −4.44 | .51 |

| PWD dyadic strain | 0.57 (1.03) | 0.56 | .08 | 0.39 (1.17) | 0.33 | .04 |

| Caregiver type (non-spouse)a | 5.23 (1.27)*** | 4.11 | .48 | 2.87 (1.43)* | 2.01 | .26 |

| Random effects | Variance component | χ2 | df | Variance component | χ2 | df |

| AA PWD | 23.27 | 287.14*** | 2 | 13.32 | 182.19*** | 8 |

| AA caregiver | 28.37 | 331.73*** | 2 | 18.10 | 233.58*** | 8 |

| Model comparisonb χ2 (df) | 43.93 (24)** | |||||

Non-spouse is referent.

Deviance statistics compare conditional model (i.e. covariates) to unconditional (i.e. no covariates) model. AA = African American; PWD = person with dementia; b = unstandardized coefficient; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SE = standard error; effect size r , .30 (medium),.50 (large).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Predicting dyadic QOL

QOL of African-American PWDs was significantly associated with their perceived decision-making involvement, t(55) = 2.85, p < .01), and type of caregiver, t(55) = 4.11, p < .001). There was a medium effect size for both decision-making involvement (r = .36) and type of caregiver (r = .48). African-American PWDs who reported less decision-making involvement and whose caregivers were non-spouses were significantly more likely to have worse QOL. Similarly, QOL of African-American caregivers was associated with the caregiver type, t(55) = 2.01, p < .05), and caregiver reported dyadic strain, t(55) = −4.44, p < .001). There was a small effect size for caregiver type (r = .26) and a large effect size for dyadic strain (r = .51). African-American caregivers experienced significantly worse QOL when they were non-spouses of the PWD and when they reported greater dyadic relationship strain with the PWD. Thus, these findings respond to our second research question.

Discussion

Little is known about what influences QOL in African-American dementia dyads. Specifically, it is unknown what family structures and role functions are associated with QOL within the context of African-American dementia dyads. Using the Negro Family as a Social System as a conceptual model, we were able to examine variables that are culturally relevant to African-American dementia dyads. The results support the use of the Negro Family as Social System as a model by emphasizing the interdependence and heterogeneity within African-American dementia dyads’ QOL. Several findings are important. First, QOL of African-American PWDs and their caregivers covaried, implying the interdependent nature of the dementia caregiving process. Second, African-American PWDs reported significantly worse QOL than their African-American caregivers. Lastly, African-American PWDs who perceived less decision-making involvement and had non-spouse caregivers experienced worse QOL; whereas, African-American caregivers who reported greater dyadic relationship strain and were non-spouse caregivers experienced worse QOL.

The current study builds on the previous research that has examined QOL of PWDs and their caregivers using a dyadic approach (Moon, Townsend, Dilworth-Anderson, & Whitlatch, 2016; Moon et al., 2017). In the current study’s findings, African-American PWDs, on average, reported significantly worse QOL than African-American caregivers, which has been found (Moon et al., 2017). Although, the finding regarding African-American PWDs QOL is not a surprising finding. This study is one of the first to examine the covariation of QOL within African-American dementia dyads, which has been supported in dementia caregiving research (Moon et al., 2017) as well as more broad illness caregiving literature (Lyons & Lee, 2018). QOL was low-moderately correlated within dyads, suggesting the importance of focusing on QOL at the dyadic level to better understand the interpersonal factors associated with dyads most at risk for worse QOL.

We found three interpersonal factors associated with QOL of African-American dementia dyads—type of caregiver, decision-making involvement of African-American PWDs and dyadic strain reported by African-American caregivers. Regarding QOL of both members of African-American dementia dyads, type of caregiver or family structure was significantly associated with worse QOL for both PWDs and their caregivers. In both cases being a non-spouse caregiver (predominantly daughters and daughters-in-law) was significantly associated with worse QOL. Our results suggest being a spouse caregiver has a protective effect on QOL for that caregiver and the PWD for whom they provide care. Divergent to our findings, Pinquart and Sorensen (2011) found spouse caregivers reported greater psychological distress in caregiving when compared to both adult children and adult children-in-law caregivers. The distress experienced by spouse caregivers were associated with several sociodemographic characteristics including greater amounts of caregiving, their own perceived poorer physical health and depressive symptoms (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2011). Those findings suggest being a spouse caregiver had a negative effect on their QOL. Given these contrary results, future research is warranted. Our analysis did not explicitly examine daughter/daughter-in-law caregivers, but they were the majority of our non-spouse caregivers. When caregivers were examined further by relationship, Conde-Sala, Garre-Olmo, Turro-Garriga, Vilalta-Franch, and Lopez-Pousa (2010) found daughter caregivers’ perception of PWDs’ QOL was significantly related to more negative reports of depressive symptoms, social burden and feelings of guilt experienced by these daughter caregivers. Among non-spouse caregivers in two studies, the burden experienced by daughter caregivers was significantly more than male non-spouse caregivers (e.g. sons) (Conde-Sala et al., 2010) or (e.g. [grand]sons) (Laporte Uribe et al., 2017). Their perception of burden could result from the internalization of psychological distress experienced by daughter caregivers. Daughter caregivers often have multiple family demands while caring for their parent with dementia. Yet, Laporte Uribe et al. (2017) also found female caregivers reported significantly greater personal development related to caregiving. Similarly, positive attributes of caregiving have been found in studies of African-American caregivers (Dilworth-Anderson, Williams, & Gibson, 2002). The experiences of daughter/daughter-in-law caregivers cannot be examined in isolation. Within these dyads with predominantly daughter/daughter-in-law caregivers, post hoc analysis revealed most of the African-American PWDs were widowed. The death of the PWDs’ spouses could result in an inability to meet certain responsibilities (and/or unexpected new responsibilities) placed on the family (particularly on African-American non-spouse caregivers) by the wider society (Billingsley, 1968), which may have contributed to their dyadic strain.

The level of dyadic strain reported by African-American caregivers played a significant role in predicting their QOL. Closer examination of the DRS items reveal African-American caregivers reported greater dyadic strain, anger and depressive symptoms regarding caregiving for African-American PWDs. Based on the Negro Family as a Social System, healthy family functioning is measured by the ability of African-American dementia dyads to meet the instrumental and expressive role functions of the family (Billingsley, 1968). Our study findings suggest African-American caregivers are more overwhelmed and experience greater dyadic strain within the dyadic relationship than previously identified in dementia caregiving literature (Haley et al., 2004). The interpersonal relationship between African-American caregivers and African-American PWDs is significant in determining their QOL. Thus, interventions to improve QOL of African-American caregivers will need to take into consideration the dynamics of the relationship within African-American dementia dyads. Because the increased strain or stress reported by African-American caregivers (while controlling for the strain of African-American PWDs) does not seem to translate the same way to the African-American PWD, at least not when decision-making involvement is included. The quality of the relationship is more protective for the African-American caregivers; whereas, being more involved with decision-making appears to be more protective for the African-American PWDs.

African-American PWDs who perceived less decision-making involvement were found to have significantly worse QOL (Menne et al., 2009). Our findings highlight the importance of including African-American PWDs in everyday decision making. Over the last few decades, research focused on the values and preferences of PWDs has supported the involvement of PWDs in everyday decision-making (Menne et al., 2008; Menne & Whitlatch, 2007). The current study strongly reinforces the need to involve African-American PWDs in decision-making during the mild-to-moderate disease trajectory. The lack of decision-making involvement may be especially difficult for African-American older adults given their previous respected, leadership role in many African-American families and the African-American community. Decision-making involvement in dementia dyads has been described as evolving from supported to substitute decision-making during the disease trajectory (Samsi & Manthorpe, 2013). Yet, future research with larger studies is needed to determine if decision-making involvement within African-American dementia dyads follows this same evolution.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. The size of the sample was relatively small, limiting the number of variables included in the model. Although not statistically significant in the current study, the moderate effect sizes of perceived decision-making involvement of African-American PWDs by their African-American caregivers and dyadic strain of African-American caregivers by the African-American PWDs suggest further examination of these interpersonal factors in larger African-American samples are warranted. The study was cross sectional; therefore, no causal inferences can be made or examination of changes in QOL over time. Future studies should include longitudinal designs that allow African-American dementia dyads to be their own control without relying or comparing to other racial or ethnic groups and for complete examination of the conceptual framework of the Negro Family as a Social System. In addition, examining biobehavioral variables may add a more objective component to the subjective QOL data gained through surveys.

Strengths and implications

Despite the limitations, there are several notable strengths in the current study. The current study findings point to taking a broader view when looking at QOL in African-American dementia dyads. The study highlights the need for African-American dyadic research and examining the interpersonal factors within African-American dementia dyads. Findings suggest the importance of the type of caregiver, decision-making involvement of African-American PWDs and dyadic relationship strain reported by African-American caregivers on QOL of African-American dementia dyads.

Our findings elucidate the complexity of caregiving and the gaps in our understanding regarding a subgroup of African-American caregivers with limited research—African-American non-spouse caregivers (who were predominantly daughters/daughters-in-law). Sixty percent of caregivers are female and 20% (5.6 million) are African-American (National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP, 2015). Our study sample is consistent with both African-American female caregivers and African-American daughter caregivers being the majority. Kim et al. (2018) found African-American caregivers with multiple caregiving roles experienced worse self-rated health when compared to caregivers with only one caregiving role, possibly related to limited opportunities to care for their own health. Well-meaning providers cannot overlook the critical role and potential fragile nature of African-American non-spouse caregivers when they attend appointments with African-American PWDs. These visits may be one of the few points of contact for African-American non-spouse caregivers with providers and their risk of worse QOL should be addressed.

In the clinical setting, factors that influence QOL of both members of African-American dementia dyads should be addressed. For example, encouraging the inclusion of African-American PWDs in decision-making during the early stages of the disease trajectory preserves their position in the family and respect instilled by African-American culture. In addition, it is important to evaluate the QOL of both African-American PWDs and their African-American caregivers. Relying solely on secondary proxy report rather than on the responses of African-American PWDs or not probing African-American caregivers to better understand their situation, clinicians may miss key factors that would highlight their risk of worse QOL. Future research should continue to identify African-American dementia dyads at risk for worse QOL through the examination of decision-making involvement of both African-American PWDs and their African-American caregivers.

This novel study elucidates the need to examine the African-American PWD and their African-American caregiver through a dyadic lens that is supported by our findings and the interdependence in African-American culture. Greater attention is needed to investigate the African-American dementia dyad as a unit, understand cultural nuance and identify other dyadic characteristics (e.g. sex of the caregiver) that put African-American PWDs and their caregivers at greater risk for worse QOL. These discoveries will foster strategies to best support African-American dementia dyads in both research and clinical practice.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jonas Veterans Healthcare Scholarship; Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) School of Nursing Dean’s Alumni Scholarship; OHSU School of Nursing Pierce Scholarship and SAMSHA-ANA. Funding for this manuscript was made possible (in part) by Grant Number 1H79SM080386-01. The views expressed in written training materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government (all K.B). This work was supported by grants from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, The AARP Andrus Foundation, The Retirement Research Foundation, The National Institute of Aging (P50AG08012), and The National Institute of Mental Health (R01070629) (all C.J.W).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2018). 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 14, 367–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett RC, Marshall NL, Raudenbush SW, & Brennan RT (1993). Gender and the relationship between job experiences and psychological distress: A study of dual-earner couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 794–806. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley A (1968). Black families in White America. New York, NY: Touchstone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley A (1992). Climbing Jacob’s ladder. New York, NY: Touchstone Books. doi: 10.1086/ahr/99.1.289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brod M, Stewart AL, Sands L, & Walton P (1999). Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in dementia: The dementia quality of life instrument (DQoL). The Gerontologist, 39(1), 25–35. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.1.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgener S, & Twigg P (2002). Relationships among caregiver factors and quality of life in care recipients with irreversible dementia. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 16(2), 88–102. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200204000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark PA, Tucke SS, & Whitlatch CJ (2008). Consistency of information from persons with dementia: An analysis of differences by question type. Dementia, 7(3), 341–358. doi: 10.1177/1471301208093288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coeling HV, Biordi DL, & Theis SL (2003). Negotiating dyadic identity between caregivers and care receivers. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 35(1), 21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Sala JL, Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Vilalta-Franch J, & Lopez-Pousa S (2010). Quality of life of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Differential perceptions between spouse and adult child caregivers. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 29(2), 97–108. doi: 10.1159/000272423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, & Gibson BE (2002). The cultural influence of values, norms, meanings, and perceptions in understanding dementia in ethnic minorities. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 16(Suppl. 2), S56–S63. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200002-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, & Gibson BE (2002). Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research: A 20-year review (1980–2000). The Gerontologist, 42(2), 237–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina N, Page TE, Daley S, Brown A, Bowling A, Basset T, … Banerjee S (2017). Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 13(5), 572–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF, & Whitlatch CJ (2001). Are persons with cognitive impairment able to state consistent choices? The Gerontologist, 41(3), 374–382. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.3.374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, & Davey Smith G (2006). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(1), 7–12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE, Gitlin LN, Wisniewski SR, Mahoney DF, Coon DW, Winter L, … Ory M (2004). Well-being, appraisal, and coping in African-American and Caucasian dementia caregivers: Findings from the REACH study. Aging & Mental Health, 8(4), 316–329. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001728998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Allen RS, Wang SY, Park S, Perkins EA, & Parmelee P (2018). The relation between multiple informal caregiving roles and subjective physical and mental health status among older adults: Do racial/ethnic differences exist? Gerontologist, 59, 499–508. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte Uribe F, Heinrich S, Wolf-Ostermann K, Schmidt S, Thyrian JR, Sch€afer-Walkmann S, & Holle B (2017). Caregiver burden assessed in dementia care networks in Germany: Findings from the DemNet-D study baseline. Aging & Mental Health, 21(9), 926–937. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1181713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP (1991). A multidimensional view of quality of life in frail elders. In Birren JE, Lubben JE, Rowe JC, & Deutchman DE (Eds.), The concept and measurement of quality of life in the frail elderly (pp. 3–27). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, & Teri L (1999). Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: Patient and caregiver reports. Journal of Mental Health and Aging, 5, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, & Teri L (2002). Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(3), 510–519. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, & Lee CS (2018). The theory of dyadic illness management. Journal of Family Nursing, 24(1), 8–28. doi: 10.1177/1074840717745669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Zarit SH, Sayer AG, & Whitlatch CJ (2002). Caregiving as a dyadic process: Perspectives from caregiver and receiver. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(3), P195–P204. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.P195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, Small BJ, & Saghafi EM (2010). Review and meta-analysis of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(3), 325–342. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9216-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, Judge KS, & Whitlatch CJ (2009). Predictors of quality of life for individuals with dementia: Implications for intervention. Dementia, 8(4), 543–560. doi: 10.1177/1471301209350288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, Tucke SS, Whitlatch CJ, & Feinberg LF (2008). Decision-making involvement scale for individuals with dementia and family caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other DementiasV R, 23(1), 23–29. doi: 10.1177/1533317507308312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, & Whitlatch CJ (2007). Decision-making involvement of individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist, 47(6), 810–819. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Lee CS, Whitlatch CJ, & Lyons KS (2018). Involvement of hospitalized persons with dementia in everyday decisions: A dyadic study. The Gerontologist, 58(4), 644–653. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Whitlatch CJ, Lee CS, & Lyons KS (2018). Incongruent perceptions of the care values of hospitalized persons with dementia: A pilot study of patient-family caregiver dyads. Aging & Mental Health, 22(4), 489–496. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1280766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Whitlatch CJ, & Lyons KS (2016). Shared decision-making in dementia: A review of patient and family carer involvement. Dementia, 15(5), 1141–1157. doi: 10.1177/1471301214555542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon H, Townsend AL, Dilworth-Anderson P, & Whitlatch CJ (2016). Predictors of discrepancy between care recipients with mild-to-moderate dementia and their caregivers on perceptions of the care recipients’ quality of life. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other DementiasV R, 31(6), 508–515. doi: 10.1177/1533317516653819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon H, Townsend AL, Whitlatch CJ, & Dilworth-Anderson P (2017). Quality of life for dementia caregiving dyads: Effects of incongruent perceptions of everyday care and values. The Gerontologist, 57(4), 657–666. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the US (2015 Research Report).Retrieved from https://www.African-Americanrp.org/content/dam/African-Americanrp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united-states-2015-report-revised.pdf

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, & Hogan H (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States (P25–1140). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/library/publications/2014/demo/p25-1140.html

- Pinquart M, & Sorensen S (2011). Spouses, adult children, and children-in-law as caregivers of older adults: A meta-analytic comparison. Psychology and Aging, 26(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1037/a0021863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers SM, & Whitlatch CJ (2016). Measuring cultural justifications for caregiving in African American and White caregivers. Dementia, 15(4), 629–645. doi: 10.1177/1471301214532112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, & Congdon R (2017). HLM 7.03 for Windows Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Samsi K, & Manthorpe J (2013). Everyday decision-making in dementia: Findings from a longitudinal interview study of people with dementia and family carers. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(6), 949–961. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer AG, & Klute MM (2005). Analyzing couples and families: Multilevel methods. In Bengtson VL, Acock AC, Allen KR, Dilworth-Anderson P, & Klein DM (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theory & research (pp. 289–313). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, & Beach SR (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The Caregiver health effects study. JAMA, 282(23), 2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, & Martire LM (2004). Family caregiving of persons with dementia: Prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12(3), 240–249. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200405000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebern MD, & Whitlatch CJ (2007). Dyadic relationship scale: A measure of the impact of the provision and receipt of family care. The Gerontologist, 47(6), 741–751. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F (2003). Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr., & Sherbourne CD (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. PharmacoEconomics, 2(2), 98–483. doi: 10.1007/BF03260127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]