Abstract

Background:

Limited research has focused on longitudinal interrelations between perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms beyond the first postpartum months. This paper tested an alternative primary hypothesis within the stress process model examining whether perceived stress mediated the association between perceived social support and depressive symptoms from 1 to 24 months postpartum. Secondary purposes examined whether these factors: (1) changed from 1 to 24 months postpartum and (2) predicted depressive symptoms.

Methods:

Women (N = 1,316) in a longitudinal cohort study completed validated measures of perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms at 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months postpartum via telephone interviews. Analyses examined changes in psychosocial factors (repeated measures ANOVA) and the extent to which perceived social support and perceived stress predicted depressive symptoms and supported mediation (linear regression).

Results:

Perceived social support decreased, perceived stress increased, and depressive symptoms remained constant from 1 to 18 months, then increased at 24 months. Low perceived social support predicted 6-month depressive symptoms, whereas perceived stress predicted depressive symptoms at all time points. Perceived stress mediated the association between perceived social support and depressive symptoms across 24 months such that low perceived social support predicted perceived stress, which in turn predicted depressive symptoms.

Conclusions:

Intervention scientists may want to focus on strengthening perceived social support as a means to manage perceived stress in an effort to prevent a long-term trajectory of depression.

Introduction

Postpartum depression, a major depressive episode within the first four weeks after childbirth, is experienced by 11–17% of mothers world-wide (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition [DSM-5]; American Psychological Association [APA], 2013; Shorey et al., 2018; Woody, Ferrari, Siskind, Whiteford, & Harris, 2017). Actual prevalence, however, may be higher given estimates show that more than half of women with postpartum depression often go undiagnosed (Thurgood, Avery, & Williamson, 2009). Postpartum depression has detrimental effects on the mother (e.g., chronic depression; McCall-Hosenfeld et al., 2016) and the infant (e.g., breastfeeding problems, maternal-infant bonding) as well as mother-partner bonding (Becker, Weinberger, Chandy, & Schmukler, 2016; Behrendt et al., 2016; Dias & Figueiredo, 2015; Mamun et al., 2009). Thus, research and public health efforts are needed to identify modifiable factors to reduce depressive symptoms and develop effective and timely interventions to manage and/or prevent the onset of symptoms.

Many women have reported feeling lonely after birth because the general focus is on the newborn baby and not the mother (ACOG, 2018; Christenson, Johansson, Reynisdottir, Torgerson, & Hemmingsson, 2016). Subsequently, some women report experiencing low levels of perceived social support and high levels of perceived stress during the postpartum period (Li, Long, Cao, & Cao, 2017; Robertson, Grace, Wallington, & Stewart, 2004). Low perceived social support is associated with postpartum depressive symptoms and this association can be apparent up to 24-months postpartum (Ghaedrahmati, Kazemi, Kheirabadi, Ebrahimi, & Bahrami, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Milgrom, Hirshler, Reece, Holt, & Gemmill, 2019; Norhayati, Nik Hazlina, Asrenee, & Wan Emilin, 2015; Reid & Taylor, 2015; Schwab-Reese, Schafer, & Ashida, 2017; Tambag, Turan, Tolun, & Can, 2018). Many women express the desire for more support to help with adjusting to new roles as a mother and caretaker as well as managing the physical and psychological changes to their body after delivery (Christenson et al., 2016). Women have reported that when these needs are not met, it increases experiences of postpartum depressive symptoms (Christenson et al., 2016). Moreover, the postpartum period can introduce women to daily life stressors not previously experienced (e.g., caretaking for a newborn, sleep disturbances, balancing work and life responsibilities), increasing overall levels of perceived stress. This high level of perceived stress during the postpartum period may elevate or augment depressive symptoms (Ghaedrahmati et al., 2017; Grote & Bledsoe, 2007; Norhayati et al., 2015; Razurel, Kaiser, Antonietti, Epiney, & Sellenet, 2017; Robertson et al., 2004; Schwab-Reese et al., 2017). Given the elevated risk of postpartum depressive symptoms due to poor perceived social support and high perceived stress, researchers have attempted to better understand the factors as a whole and examine their complex interrelations.

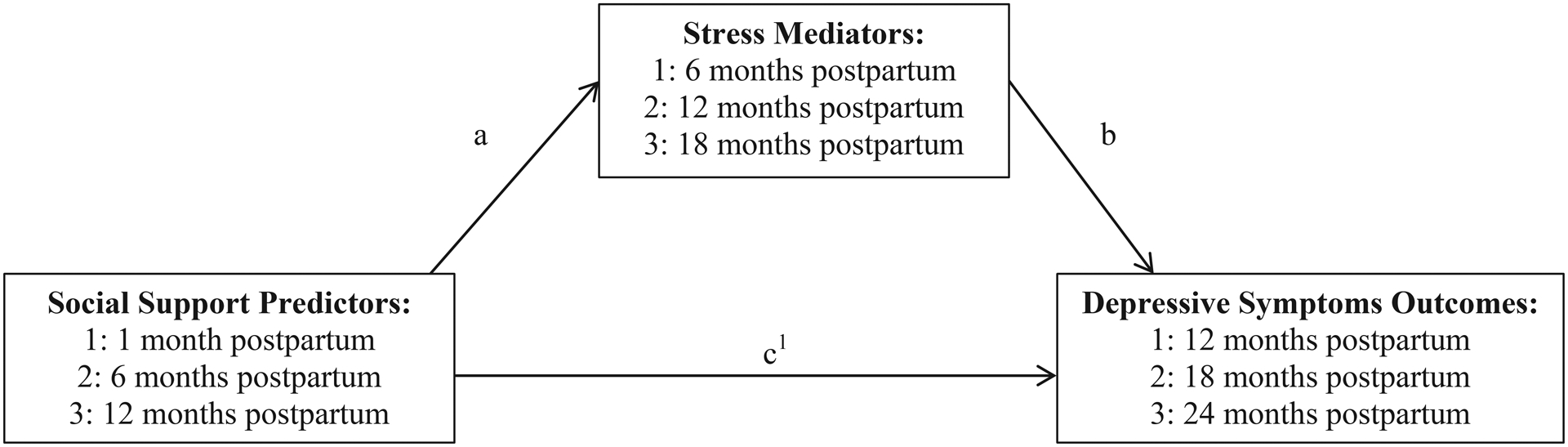

To this end, past studies have examined perceived social support, perceived stress, and postpartum depressive symptoms under the Stress Process Model whereby perceived social support is a mediator of the association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms (Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, & Mullan, 1981; Pearlin et al., 1981; Razurel et al., 2017; Schwab-Reese et al., 2017). The Stress Process Model, however, does not take into account multidirectional explanations of depressive symptoms or what happens when mediation by perceived social support is minimal. For instance, Schwab-Reese et al. (2017) found that perceived social support and perceived stress were associated with depressive symptoms during the postpartum period, however mediation by perceived social support was minimal. This suggests that there may be other potential explanations or mechanisms that may better explain the interrelations between these factors and postpartum depressive symptoms. For example, an alternative explanation could be that poor perceived social support predicts perceived stress, and in turn explains postpartum depressive symptoms. Researchers have suggested that low perceived social support is a source of postpartum perceived stress (Andersson & Hildingsson, 2016; Cornish & Dobie, 2018), and that this increase in perceived stress can increase the risk of depressive symptoms. To this end, our study tested the alternative hypothesis that perceived stress rather than perceived social support mediates the association between poor perceived social support and postpartum depressive symptoms up to 24-months postpartum (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mediation Conceptual Framework.

Examining 6, 12, and 18 month postpartum stress as mediators between 1, 6, and 12 month postpartum social support and 12, 18, and 24 month postpartum depressive symptoms. a = pathway between predictor and mediator; b = pathway between mediator and outcome; c1 = pathway between predictor and outcome (direct effect).

Furthermore, although clinicians strive to provide optimal support for postpartum women, clinical care during the postpartum period is generally limited to a single visit at 4–6 weeks (unless there are considerable issues after birth requiring more intensive care). This decreases the chances that women will be diagnosed with postpartum depression beyond 4–6 weeks after birth (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2018). Subsequently, symptoms of depression after this visit can often go under-diagnosed or under-treated (Becker et al., 2016). To this end, researchers and clinicians have called for an extension of the time period for the clinical criteria (i.e., 6 months postpartum) given the research evidence showing that symptoms of depression are present long after four weeks post-birth (O’Hara & McCabe, 2013). However, research examining longitudinal predictors of depressive symptoms beyond the first few postpartum months is scant. Most studies focus on depressive symptoms before, during, or immediately after pregnancy. Examining the extent to which perceived social support and perceived stress longitudinally predicts depression is important because these predictors may change over time and thus increase the risk of depression at certain points during the postpartum period. For example, researchers have shown that perceived instrumental social support (e.g., childcare, buying diapers) decreases throughout the first year of the postpartum period, which can lead to women feeling lonely and experiencing negative psychological well-being (Chen et al., 2016; Negron et al., 2013). Researchers have also found that women who report high perceived stress during the postpartum period do not see any improvement up to 3-years postpartum (Mughal et al., 2018). In contrast, researchers have found that some women exhibit a trajectory where depression continuously increases throughout the first year of the postpartum period (Bayrampour, Tomfohr, & Tough, 2016). Nevertheless, changes in these psychosocial factors support the premise that maternal psychosocial well-being may be variable during the postpartum period. Given the discrepancy in the time period for defining postpartum depression and the fact that psychosocial well-being is variable over the course of the postpartum period, there is a need to understand the contributing factors of depressive symptoms beyond the first four postpartum weeks.

The first purpose of this secondary analysis from the First Baby Study was to examine change in perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms across 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months postpartum. The second purpose was to examine whether perceived social support and perceived stress predicted depressive symptoms over time. The third purpose was to explore whether perceived stress mediated the association between perceived social support and depressive symptoms. Based on past evidence (Christenson et al., 2016; Ghaedrahmati et al., 2017; Grote & Bledsoe, 2007; Norhayati et al., 2015; Reid & Taylor, 2015; Robertson et al., 2004; Schwab-Reese et al. 2017) and Pearlin and colleague’s (1981) urging to consider alternative pathways, we proposed an alternative hypothesis that perceived stress would mediate the association between perceived social support and depressive symptoms over the 24-month postpartum period. We also hypothesized: (a) perceived social support would decrease over the 24 months, whereas perceived stress and depressive symptoms would increase, and (b) lower perceived social support and higher perceived stress would predict depressive symptoms after accounting for the influence of past depressive symptoms.

Methods

Participants

Women (N = 3,006) were first time mothers from a larger longitudinal study, the First Baby Study (FBS; Kjerulff et al., 2013), examining the association between mode of delivery and subsequent childbearing outcomes. Participants were recruited through flyers at hospitals, childbirth classes, low-income clinics, and ultrasound/community health centers and through local press releases and advertisements. Inclusion criteria were: 18–35 years old, residents of Pennsylvania, nulliparous, and able to read and speak English or Spanish. A more detailed explanation of the FBS can be found elsewhere (Kjerulff et al., 2013). Because we were interested in understanding depressive symptoms up to 24 months after delivery and not symptoms from a subsequent pregnancy during this follow-up period, women were excluded from these secondary analyses if they became pregnant again (n = 1,657); of the women who had not become pregnant, women were excluded if they did not report baseline demographics (n = 33). Thus, a final sample of N = 1,316 was used for the study analyses. Procedures

This study used data collected from telephone interviews at 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months postpartum. Women were surveyed via telephone interviews by trained, professional interviewers employed by the Penn State Harrisburg Center for Survey Research and were asked to respond to questions regarding their experiences with pregnancy and childbearing. The FBS was approved by the Penn State College of Medicine and participating hospital Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

Maternal postpartum depressive symptoms were assessed with an adapted version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987). The valid and reliable EPDS is commonly used (Daley et al., 2015; Di Florio et al., 2016) and includes 10 items (e.g., “I have been so unhappy that I have been crying”) rated on a 4-point response scale ranging from 1 (e.g., Yes, most of the time) to 4 (e.g., No, not at all; Cox et al., 1987). Based on past evidence from pilot studies (Abbasi, Chuang, Dagher, Zhu, & Kjerulff, 2013; Kinsey, Baptiste-Roberts, Zhu, & Kjerulff, 2014; McCall-Hosenfeld et al., 2016), the item “Things have been getting on top of me” was changed to “I have had trouble coping” because women found the term “getting on top of me” confusing. Also, the item “The thought of harming myself has occurred to me” was changed to “The thought of harming myself or others has occurred to me” because postpartum depression has been linked to homicidal ideation, particularly as concerns of harming the infant (Hatters & Resnick, 2007; Humenik & Fingerhut, 2007; Jennings, Ross, Popper, & Elmore, 1999). To our knowledge, we are the first researchers to change this item to include homicidal ideation in addition to self-harm. These modified items exhibited good corrected item-total correlations throughout the study. Total scores were calculated, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. Women were also categorized as ‘no possible depression’ (EPDS < 10) or ‘possible depression’ (EPDS ≥ 10), consistent with the literature (Gibson, McKenzie-McHarg, Shakespeare, Price, & Gray, 2009). It is important to note that this measure is not a clinical diagnostic tool for postpartum depression, but rather a measure of postpartum depressive symptoms. Internal consistencies of the modified EPDS were good at all time points (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.80–0.84).

An adapted version of the Prenatal Psychosocial Profile Hassles Scale was also used to measure perceived stress (Curry, Campbell, & Christian, 1994; Misra, O’Campo, & Strobino, 2001). The scale was originally developed for low-income, minority women living in urban areas. Pilot testing in our area indicated that two items exhibited poor item-total correlations in our study population (primarily middle- and upper-income women living in rural and suburban areas) because very few of the respondents reported experiencing those problems. Thus, a modified version of the scale was used: the items “sexual, emotional or physical abuse” and “problems with alcohol or drugs” were changed to “fights with partner” and “fights with other family members.” We chose these new items based on several focus group studies of women during and after pregnancy. These new items exhibited good corrected item-total correlations, as we have reported previously (Kinsey et al., 2014; Phelan, DiBenedetto, Paul, Zhu, & Kjerulff, 2015). Women rated 12 items that may have occurred and caused them to feel stressed (i.e., “worries about food, shelter, health care, and transportation,” and “problems with the baby”) using 4-point response options ranging from 1 (no stress) to 4 (severe stress). Total scores were calculated, with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress. Internal consistencies of the adapted scale were acceptable at all time points (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.71–0.77).

Perceived social support was measured using the 5-item validated form of the Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS; McCarrier et al., 2011), a commonly utilized shortened scale (e.g., Ford-Gilboe et al., 2017). Women were asked to rate 5 items (e.g., “someone to confide in or talk to about your problems”) on a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Total scores were calculated, with higher scores indicating greater perceived social support. Internal consistencies were good to excellent at all time points (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.87–0.92).

Demographics.

Women reported age, race/ethnicity, family income, marital status, education, current height, and current weight. Pre-pregnancy weight and height was retrospectively reported to calculate pre-pregnancy BMI. Based on past research (Fisher et al., 2016; Palumbo, Mirabella, & Gigantesco, 2017; Salehi-Pourmehr et al., 2018; Silverman et al., 2017), each analysis was run unadjusted and adjusted for the following demographics: weight status, marital status, education, income, age, and race. For example, women who are Caucasian, older, and divorced/separated are at an elevated risk for postpartum depressive symptoms (Fisher et al., 2016; Palumbo et al., 2017). Further, researchers have found that weight status is associated with postpartum depression such that a higher weight status (i.e., having overweight or obesity) is associated with an increased risk of postpartum depressive symptoms, potentially due to dysregulation of biological mechanisms (e.g., HPA axis regulation; Salehi-Pourmehr et al., 2018; Silverman et al., 2017).

Data Analysis

All data was analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24.0). Means, standard deviations, and percentages were used to examine demographic variables and descriptives of primary study variables across the total sample controlling for weight status, marital status, education, income, age, and race. Partial correlations also controlling for these demographic factors were conducted to examine associations between all study variables across the 24 months. Repeated Measures ANOVA examined changes in primary study variables across the 24 months. Linear regression determined whether perceived social support and perceived stress were predictors of postpartum depressive symptoms. Regression models included perceived social support or perceived stress from the prior time period while controlling for past depressive symptoms. Finally, Hayes (2013) methods using the PROCESS command in SPSS examined whether postpartum perceived stress mediated the associations between perceived social support and depressive symptoms. Mediation models examined each pathway prospectively (i.e., independent variable at T1, mediator at T2, and dependent variable at T3), which resulted in three parallel models covering unique 12-month spans (Figure 1): (1) 1-month perceived social support (predictor) and 6-month perceived stress (mediator) predicting 12-month depressive symptoms (outcome), (2) 6-month perceived social support (predictor) and 12-month perceived stress (mediator) predicting 18-month depressive symptoms (outcome), and (3) 12-month perceived social support (predictor) and 18-month perceived stress (mediator) predicting 24-month depressive symptoms (outcome). These time points were chosen because they correspond with when the data were collected for the FBS. A significant indirect effect (i.e., predictor predicts the outcome through the mediator) meant the mediator significantly mediated the association between the predictor and outcome. Hayes (2013) macro features bias-corrected bootstrapping, which determines the effect size of the indirect effect (i.e.,β) alongside a 95% confidence interval (i.e., significant indirect effect sizes signaled by p-values below 0.05 and confidence intervals that do not include zero). Repeated Measures ANOVAs, linear regressions, and mediation models analyses adjusted for weight status, marital status, education, income, age, and race did not differ from unadjusted models; thus, only the unadjusted analyses are presented in detail. Repeated Measures ANOVAs omit observations listwise, therefore if any observations over time were missing for a participant, that participant was removed. For perceived social support, n = 3 women were excluded, for perceived stress, n = 9 women were excluded, and for depressive symptoms, n = 10 women were excluded. For the linear regression and mediation models, we included only women with no missing data for perceived social support, perceived stress, and perceived depressive symptoms at all time points (n = 1,301). There were no significant differences in study variables between women who did and did not complete all measures.

Results

Mean pre-pregnancy BMI was 26.19 (SD = 5.96; range = 14.14 to 45.52) and mean age was 27.6 years old (SD = 4.2); the majority of participants were married or partnered (90.0%), White (86.9%), had a college degree (58.4%), and reported a family income ≥ $75,000 (46.1%; Table 1). We identified an increase in the frequency with which women reported scale values that indicated possible depression (i.e., EPDS ≥ 10; Gibson et al., 2009) at 1 (9.5%), 6 (8.3%), 12 (10.2%), 18 (10.1%), and 24 months (12.1%) with significant increases from 6 to 12 months and 18 to 24 months (McNemar Test p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study sample

| Variable | Mean | SD | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 26.19 | 5.96 | |

| Age | 27.56 | 4.20 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/Partnered | 90.0 | ||

| Other | 10.0 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 86.9 | ||

| Other | 13.1 | ||

| Education | |||

| ≤ High School | 41.6 | ||

| ≥ College | 58.4 | ||

| Family Income | |||

| < $20,000 | 9.7 | ||

| $20,000–49,999 | 21.6 | ||

| $50,000–74,999 | 22.6 | ||

| ≥ $75,000 | 46.1 |

Note. SD = Standard Deviation; BMI = Body Mass Index

Change Over Time and Associations.

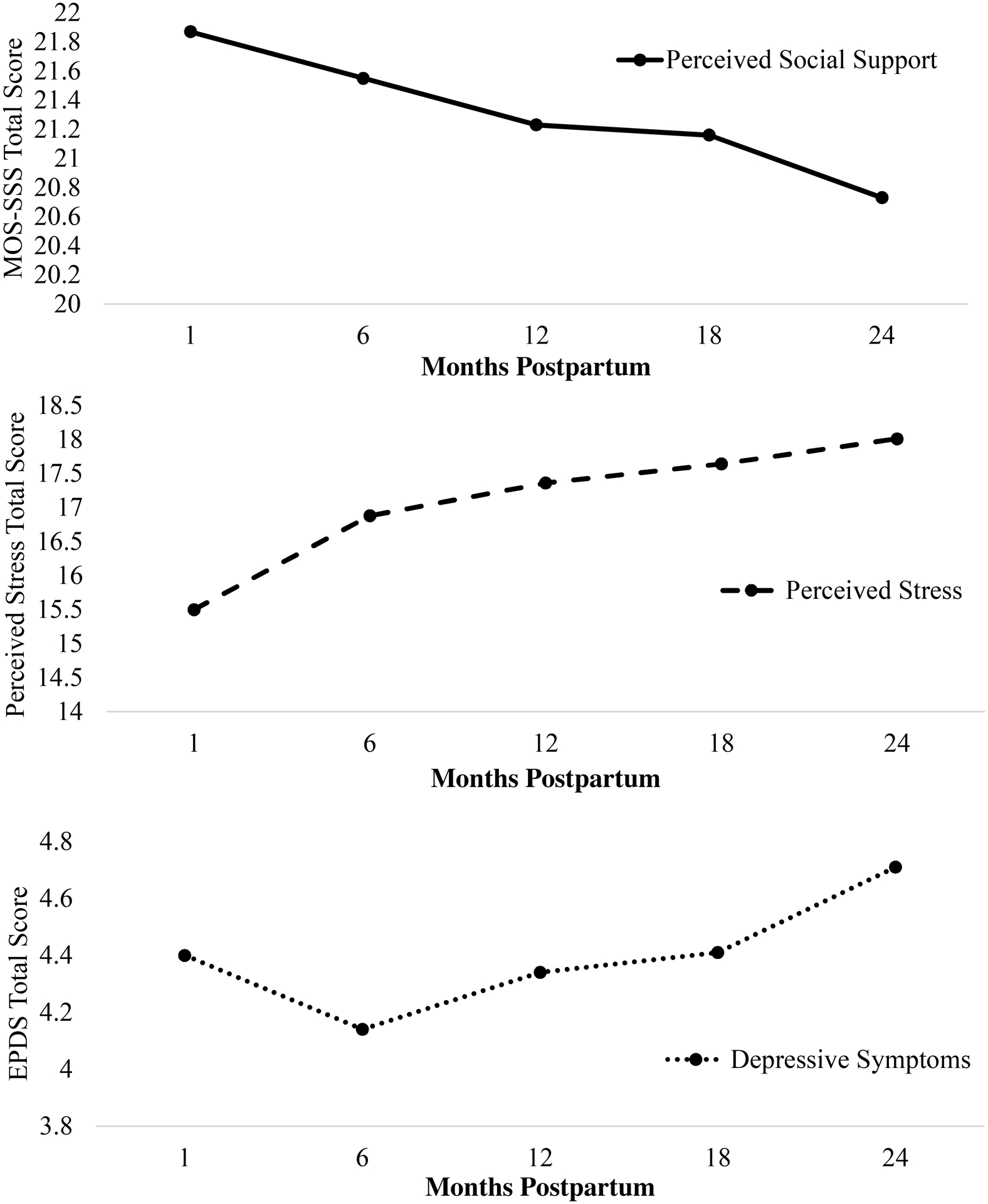

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms at each time point are presented in Table 2. Figure 2 illustrates the means over time. Repeated measures ANOVAs revealed a significant multivariate effect of time for perceived social support, Wilks’ Lambda (Λ) = 0.89, F(4, 1309) = 39.97, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.11, perceived stress, Λ = 0.69, F(4, 1301) = 149.08, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.31, and depressive symptoms, Λ = 0.98, F(4, 1302) = 8.02, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02. Perceived social support decreased (p < 0.01) over the 24 months, except from 12 to 18 months postpartum, in which perceived social support remained constant. Perceived stress increased (p < 0.01) at each time point. Depressive symptoms remained constant until 18 months postpartum and then increased at 24 months (p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Descriptives and partial correlations controlling for maternal age, marital status, education, race, and family income among all study variables across 24 months postpartum

| 1-Month | 6-Month | 12-Month | 18-Month | 24-Month | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | St | DS | SS | St | DS | SS | St | DS | SS | St | DS | SS | St | DS | |

| 1 Month | |||||||||||||||

| SS | -- | −0.34* | −0.32* | 0.61* | −0.29* | −0.25* | 0.58* | −0.26* | −0.24* | 0.56* | −0.25* | −0.24* | 0.56* | −0.22* | −0.20* |

| St | -- | 0.44* | −0.31* | 0.60* | 0.40* | −0.31* | 0.54* | 0.35* | −0.31* | 0.48* | 0.35* | −0.28* | 0.45* | 0.30* | |

| DS | -- | −0.29* | 0.34* | 0.52* | −0.28* | 0.29* | 0.44* | −0.29* | 0.21* | 0.37* | −0.25* | 0.22* | 0.36* | ||

| 6 Months | |||||||||||||||

| SS | -- | −0.39* | −0.39* | 0.68* | −0.35* | −0.33* | 0.67* | −0.34* | −0.34* | 0.64* | −0.29* | −0.32* | |||

| St | -- | 0.59* | −0.33* | 0.70* | 0.47* | −0.38* | 0.65* | 0.47* | −0.36* | 0.63* | 0.46* | ||||

| DS | -- | −0.29* | 0.45* | 0.62* | −0.33* | 0.39* | 0.57* | −0.30* | 0.40* | 0.55* | |||||

| 12 Months | |||||||||||||||

| SS | -- | −0.40* | −0.40* | 0.69* | −0.32* | −0.32* | 0.67* | −0.29* | −0.29* | ||||||

| St | -- | 0.56* | −0.38* | 0.70* | 0.47* | −0.33* | 0.64* | 0.43* | |||||||

| DS | -- | −0.35* | 0.46* | 0.63* | −0.30* | 0.39* | 0.56* | ||||||||

| 18 Months | |||||||||||||||

| SS | -- | −0.39* | −0.39* | 0.72* | −0.33* | −0.32* | |||||||||

| St | -- | 0.59* | −0.37* | 0.69* | 0.48* | ||||||||||

| DS | -- | −0.35* | 0.49* | 0.63* | |||||||||||

| 24 Months | |||||||||||||||

| SS | -- | −0.40* | −0.40* | ||||||||||||

| St | -- | 0.59* | |||||||||||||

| DS | -- | ||||||||||||||

| Mean | 21.87 | 15.50 | 4.40 | 21.55 | 16.88 | 4.14 | 21.23 | 17.36 | 4.34 | 21.16 | 17.64 | 4.41 | 20.73 | 18.01 | 4.71 |

| SD | 3.38 | 3.12 | 3.71 | 3.40 | 3.79 | 3.72 | 3.49 | 4.09 | 3.78 | 3.58 | 4.29 | 3.92 | 3.83 | 4.18 | 4.11 |

Note.

p<0.01; SS = Social Support; St = Stress; DS = Depressive Symptoms. The mean values of the constructs are also visually represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mean scores for perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms over the 24 month postpartum period.

Note. Perceived Social Support N = 1313; Perceived Stress N = 1305; Depressive Symptoms N = 1306. Possible scale ranges varied for social support (5 to 25), stress (12 to 48), and depressive symptoms (0 to 30). MOS-SSS = Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey; EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Stress total score was measured via the Prenatal Psychosocial Profile Hassles Scale.

Pearson correlation analyses (Table 2) revealed significant associations between all study variables at all time points such that lower levels of perceived social support were associated with higher levels of perceived stress and depressive symptoms whereas higher levels of perceived stress were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Regression.

The final model including 1-month depressive symptoms, perceived social support, and perceived stress explained 31% of the variance in depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum (Table 3). Higher levels of depressive symptoms (p < 0.001) and perceived stress (p < 0.001) at 1 month were significant predictors of depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum. Perceived social support at 1 month trended towards predicting depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum (p = 0.07).

Table 3.

Predicting postpartum depressive symptoms using perceived social support and perceived stress (N = 1301)

| R2 | F | df | p | β1 | β2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicting 6-Month Postpartum Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| Block 1: Past Postpartum | 0.27 | 488.32 | 1, 1300 | <0.001 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| 1-Month | 0.52*** | 0.42*** | ||||

| Block 2 | 0.31 | 193.27 | 3, 1300 | <0.001 | ||

| 1-Month Social Support | −0.05 | |||||

| 1-Month Stress | 019*** | |||||

| Predicting 12-Month Postpartum Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| Block 1: Past Postpartum | 0.41 | 442.61 | 2, 1300 | <0.001 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| 1-Month | 0.16*** | 0.15*** | ||||

| 6-Month | 0.54*** | 0.44*** | ||||

| Block 2 | 0.42 | 235.90 | 4, 1300 | <0.001 | ||

| 6-Month Social Support | −0.06* | |||||

| 6-Month Stress | 0.13*** | |||||

| Predicting 18-Month Postpartum Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| Block 1: Past Postpartum | 0.45 | 350.94 | 3, 1300 | <0.001 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| 1-Month | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||

| 6-Month | 0.27*** | 0.25*** | ||||

| 12-Month | 0.45*** | 0.38*** | ||||

| Block 2 | 0.46 | 220.55 | 5, 1300 | <0.001 | ||

| 12-Month Social Support | −0.04 | |||||

| 12-Month Stress | 0.12*** | |||||

| Predicting 24-Month Postpartum Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| Block 1: Past Postpartum | 0.47 | 285.29 | 4, 1300 | <0.001 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| 1-Month | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||||

| 6-Month | 0.20*** | 0.20*** | ||||

| 12-Month | 0.16*** | 014*** | ||||

| 18-Month | 0.41*** | 0.34*** | ||||

| Block 2 | 0.48 | 197.16 | 6, 1300 | <0.001 | ||

| 18-Month Social Support | −0.02 | |||||

| 18-Month Stress | 0.12*** | |||||

Note.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001. df = degrees of freedom; β = standardized regression coefficients.

The final model including 1- and 6-month depressive symptoms and 6-month perceived social support and perceived stress explained 42% of the variance in depressive symptoms at 12 months postpartum. Higher levels of depressive symptoms at 1 and 6 months (p < 0.001), higher levels of perceived stress (p < 0.001), and lower levels of perceived social support (p < 0.05) at 6 months were significant predictors of depressive symptoms at 12 months postpartum (p < 0.001).

The final model including 1-, 6-, and 12-month depressive symptoms and 12-month perceived social support and perceived stress explained 46% of the variance in depressive symptoms at 18 months postpartum. Higher levels of depressive symptoms at 6 and 12 months (p < 0.001) and higher levels of perceived stress at 12 months were significant predictors of depressive symptoms at 18 months postpartum (p < 0.001). Perceived social support at 12 months was not a significant predictor of depressive symptoms at 18 months postpartum (p > 0.05).

The final model including 1-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month depressive symptoms and 18-month perceived social support and perceived stress explained 48% of the variance in depressive symptoms at 24 months postpartum. Higher levels of depressive symptoms at 6, 12, and 18 months (p < 0.001) and higher levels of perceived stress at 18 months were significant predictors of depressive symptoms at 24 months postpartum (p < 0.001). Perceived social support at 18 months was not a significant predictor of depressive symptoms at 24 months postpartum (p > 0.05).

Mediation.

Table 4 summarizes the mediation models including: (1) regression statistics for each overall model (i.e., the prediction of depressive symptoms using perceived social support as a predictor and perceived stress as the mediator), (2) the total indirect effect with mediator included, and (3) 95% confidence intervals of the indirect effect. All mediation models using postpartum perceived stress as a mediator and perceived social support significantly explained 23–25% of the variance in depressive symptoms. At all postpartum time points, perceived stress significantly mediated the association between perceived social support and depressive symptoms such that lower levels of perceived social support predicted perceived stress, which in turn predicted depressive symptoms.

Table 4.

Mediation models predicting postpartum depressive symptoms (dependent variable) using social support (predictor variable) and stress (mediator), N = 1301

| Overall Model | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | F | p-value | β (SE) | 95% CI | β (SE) | 95% CI |

| Model 1: 1-Month Social Support and 6-Month Stress Predicting 12-Month Postpartum Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| 0.23 | 194.01 | < 0.001 | −0.13 (0.03) | [−0.19, −0.08] | −0.14 (0.02) | [−0.18, −0.11] |

| Model 2: 6-Month Social Support and 12-Month Stress Predicting 18-Month Postpartum Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| 0.25 | 220.30 | < 0.001 | −0.23 (0.03) | [−0.29, −0.17] | −0.16 (0.02) | [−0.19, −0.13] |

| Model 3: 12-Month Social Support and 18-Month Stress Predicting 24-Month Postpartum Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| 0.25 | 213.00 | < 0.001 | −0.18 (0.03) | [−0.24, −0.12] | −0.16 (0.02) | [−0.20, −0.13] |

Note. β = standardized regression coefficients; SE = Standard Error; CI = confidence interval. Degrees of freedom for all overall models = (2, 1298), p < 0.001.

Discussion

The purposes of this study were to examine an alternative hypothesis that perceived stress would mediate the association between perceived social support and postpartum depressive symptoms up to 24 months after childbirth. Also, we examined changes in perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms up to 24 months postpartum. Overall, perceived social support decreased over time, whereas perceived stress increased; depressive symptoms remained constant and then increased from 18 to 24 months postpartum. Lower levels of perceived social support predicted depressive symptoms at 12 months postpartum, whereas perceived stress predicted depressive symptoms at all time points. Further, the association between perceived social support and depressive symptoms at all time points was mediated by perceived stress such that lower levels of perceived social support predicted perceived stress, in turn predicting depressive symptoms. These findings are of particular interest given that the mediation analyses were entirely prospective with the effects consistent at each time period, suggesting that during the postpartum period, perceived stress might play an important underlying role in the association between poor perceived social support and depressive symptoms.

Partial support was found for the hypothesis that perceived social support would decrease, whereas perceived stress and depressive symptoms would increase over the 24 months. Perceived social support decreased from 1 to 24 months postpartum, remaining constant from 12- to 18-months. Perceived stress increased 1 to 24 months postpartum whereas depressive symptoms remained constant, then increased at 18 to 24 months. This is consistent with past researchers’ conclusions that perceived social support declines and perceived stress increases after birth as women often perceive a shift in focus from their needs to their baby’s (Andersson & Hildingsson, 2016; Christenson et al., 2016; Cornish & Dobie, 2018). Women also feel that significant others (e.g., spouse, family members, friends) lack understanding of how much support they really need (Razurel, Bruchon-Schweitzer, Dupanloup, Irion, & Epiney, 2011). For example, while there is often a lot of support after the birth of the baby, this attention quickly declines within the first few postpartum weeks; many women feel that others do not understand this support is still needed in the continued months after childbirth as women adjust to their role as a mother along with sleepless nights, hormonal changes, and returning to work. Even one year after childbirth, women have reported that social support during the postpartum period, particularly from family members, is expected and that they should not have to ask for it (Negron, Martin, Almog, Balbierz, & Howell, 2013). Women not perceiving support up to 12-months postpartum have also reported negative experiences with psychological well-being (e.g., stress, depression; Negron et al., 2013). Nevertheless, these findings support that perceived social support and perceived stress can vary over the course of the postpartum period.

Depressive symptoms were generally stable until around 18 months postpartum, and then slightly increased from 18 to 24 months postpartum. This finding is consistent with past research (McCall-Hosenfeld et al., 2016; Mora et al., 2008) suggesting that women may have a trajectory of depressive symptoms that stabilizes during early the early postpartum period (<12 months) and increases out to 25 months. Mora and colleagues (2008) suggested that the risk of having this trajectory of a “late” increase was partly due to perceived stress. The increase in perceived stress across 24 months postpartum may have contributed to the increase in depressive symptoms later in the postpartum period. Although the overall depressive symptoms scores were low, the proportion of women with possible depression at each time point was consistent with other estimates of postpartum depression prevalence in the 11–17% range (Shorey et al., 2018; Woody et al., 2017). While it is important to note that the majority of women were not meeting the clinical definition for postpartum depression, the experience of some type of symptoms long after childbirth may be problematic due to additional stressors in the months after birth, such as changing infant needs (e.g., transition to solid foods, crawling, changing sleep patterns) that occur while women are managing their own sources of stress (e.g., trying to lose weight, returning to work, thinking about having another baby; Miller, Pallant, & Negri, 2006; Razurel et al., 2011). Nevertheless, these findings show that regardless of onset and origin, depressive symptoms are still experienced up to 2 years after childbirth, highlighting a need for long-term screening during women’s childbearing years and illustrating a gap in the literature in identifying sources of depressive symptoms in the early years after childbirth that may set the stage for long-term depression.

Partial support was found for the hypothesis that lower levels of perceived social support and higher levels of perceived stress would explain depressive symptoms after considering the role of past depressive symptoms. Past depressive symptoms explained 31–48% of the variance in depressive symptoms, which is consistent with past research suggesting the strongest predictor of depressive symptoms is past depressive symptoms (McCall-Hosenfeld et al., 2016). Further, perceived social support and perceived stress provided an additional contribution such that lower levels of 6-month perceived social support predicted 12-month depressive symptoms and higher levels of perceived stress predicted depressive symptoms at all time points. The lack of significance with perceived social support predicting depressive symptoms at 18 and 24 months postpartum may be explained by the decreasing levels of perceived social support during this time. Over time, women may have adapted to poor perceived social support, subsequently mitigating the association between poor perceived social support and depressive symptoms. The finding that perceived stress predicted depressive symptoms at all time points is consistent with past researchers’ findings showing a strong association between perceived stress and depression (Ghaedrahmati et al., 2017; Grote & Bledsoe, 2007; Norhayati et al., 2015; Robertson et al., 2004; Schwab-Reese et al., 2017).

Further, as predicted and consistent with past research (Ghaedrahmati et al., 2017; Grote & Bledsoe, 2007; Norhayati et al., 2015; Reid & Taylor, 2015; Robertson et al., 2004; Schwab-Reese et al., 2017), support was found for the hypothesis that perceived stress would mediate the association between lower levels of perceived social support and depressive symptoms. Lower levels of perceived social support predicted perceived stress, in turn predicting depressive symptoms. It may be that when women feel a lack of attention towards their needs as a new mother, this increases the risk of perceived stress (Christenson et al., 2016; Cornish & Dobbie, 2018). With perceived stress as an established independent predictor of depressive symptoms, this increase in perceived stress predicts depressive symptoms. Overall, these findings suggest women may experience depressive symptoms as far out as 24 months after childbirth and highlight the important mechanistic role that perceived stress plays in understanding the association between poor perceived social support and depressive symptoms.

This study is one of the first to prospectively examine mediating influence of perceived stress on perceived social support and depressive symptoms in women beyond the early postpartum period. Strengths include a large cohort study, prospective study design, and the ability to conduct longitudinal mediation analyses. This study also contributes to the literature by providing support for alternative explanations to the Stress Process Model and illustrating the need to better understand the complex interrelations between perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms. However, some limitations include generalizability of the study findings (e.g., sample was representative of women in Central Pennsylvania who were White, highly educated, and married). These analyses should be replicated across different cultures to address cultural differences in psychosocial well-being during the first two years of the postpartum period (e.g., culture can affect reception of social support and can affect the understanding of what the responsibilities of different family members are; Kim, Sherman, & Taylor, 2008; Lawley, Willett, Scollon, & Lehman, 2019). Another limitation was the inherent bias from self-reported based surveys. Overall, low scores of depressive symptoms could be due to underreporting, which our study was unable to assess. Also, the self-reported measure of perceived stress included symptoms associated with emotional distress, which could be confounded with depressive symptoms. Similarly, the measure of perceived social support was not able to disentangle the type or source of social support received. Future studies should further investigate the use of alternative assessments of perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms to confirm the study findings.

Implications for practice and/or policy

Overall, these study findings suggest that efforts are needed to screen and potentially treat depressive symptoms beyond the first six postpartum weeks given the change in psychosocial factors over the postpartum period, and their potential accumulating effects on maternal psychosocial well-being during a time period that is accompanied by unavoidable stressors. Further there is a need to implement early intervention strategies aimed at improving perceived social support to manage perceived stress and depressive symptoms during the postpartum period in an effort to prevent a long-term trajectory of depressive symptoms. For example, strengthening support systems may be a useful strategy to manage perceived stress, and in turn reduce depressive symptoms. Implementing strategies in early postpartum months may help to identify ways to maintain support systems longer after birth and improve perceived stress as a means to reduce depressive symptoms. However, it is important to note that explicit recommendations for how to support women throughout 24 months postpartum cannot be made given that our study did not examine other potential variables that might be associated with perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms. For example, changes in employment, relationship quality and satisfaction, and competing demands (e.g., childcare) may also help explain the associations between these psychosocial variables. Future research is needed to examine these factors as well as other potential influencing correlates to confirm these findings.

Conclusions

This novel secondary data analysis provides insight on potential long-term trajectories of depressive symptoms throughout the postpartum period. These findings also suggest an alternative framework to understand the interrelations between postpartum perceived social support, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms. Poor perceived social support predicted perceived stress, in turn predicting depressive symptoms throughout 24 months postpartum. These findings can inform future intervention development and be used to improve counseling content for depressive symptoms during the postpartum period.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank all the study participants and study staff for collecting data.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by [grant number R01HD052990] the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, NIH. The project is also funded, in part, under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco CURE funds. The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions.

Biography

Krista S. Leonard, MS, is a doctoral student in the Department of Kinesiology at Penn State. She studies predictors of postpartum depression and behavioral strategies (physical activity, healthy eating, self-regulation) to help manage weight gain during pregnancy.

Blair Evans, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Kinesiology Department at Penn State University. Blair’s interest in groups relates to how social relationships shape the behavior and wellbeing of individuals in varying populations – especially the relationships among peers in small groups.

Kristen H. Kjerulff, MA, PhD, is Professor, Departments of Public Health Sciences and Obstetrics and Gynecology, Penn State University, College ofMedicine. She studies maternity/reproductive health care and common treatments and procedures. She was Principal Investigator of the First BabyStudy

Danielle Symons Downs, PhD, is a Professor of Kinesiology and Obstetrics/Gynecology and Director of the Exercise Psychology Laboratory at Penn State. She is an expert in women’s health, motivation, and designing effective health behavior change interventions (exercise, weight) in women before/during/after pregnancy

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- 1.Abbasi S, Chuang CH, Dagher R, Zhu J, & Kjerulff K (2013). Unintended pregnancy and postpartum depression among first-time mothers. Journal of Women’s Health, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2018). Optimizing Postpartum Care. ACOG Committee Opinion. 131, e140–e150.29683911 [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association; (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth ed. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson E, & Hildingsson I (2016). Mother’s postnatal stress: An investigation of links to various factors during pregnancy and post-partum. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30, 782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayrampour H, Tomfohr L, & Tough S (2016). Trajectories of perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms in a community cohort. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77, e1467–e1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker M, Weinberger T, Chandy A, & Schmukler S (2016). Depression during pregnancy and postpartum. Current Psychiatry Reports. 18, 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behrendt HF, Konrad K, Goecke TW, Fakhrabadi R, Herpetz-Dahlmann B, & Firk C (2016). Postnatal mother-to-infant attachment in subclinically depressed mothers: Dyads at risk? Psychopathology, 49, 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen HH, Hwang FM, Lin LJ, Han KC, Lin CL, & Chien LY (2016). Depression and social support trajectories during 1 year postpartum among marriage-based immigrant mothers in Taiwan. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30, 350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christenson A, Johansson E, Reynisdottir S, Torgerson J, & Hemmingsson E (2016). Women’s perceived reasons for their excessive postpartum weight retention: A qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE, 11, e0167731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornish DL & Dobie SR (2018). Social support in the “fourth trimester”: A qualitative analysis of women at 1 month and 3 months postpartum. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 27, 233–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox JL, Holden JM, & Sagovsky R (1987). Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curry MA, Campbell RA, & Christian M (1994). Validity and reliability testing of the prenatal psychosocial profile. Research in Nursing & Health, 17, 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daley AJ, Blamey RV, Jolly K, Roalfe AK, Turner KM, Coleman S, … MacArthur C (2015). A pragmatic randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a facilitated exercise intervention as a treatment for postnatal depression: The PAM-PeRS trial. Psychological Medicine, 45, 2413–2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Florio AD, Putnam K, Altemus M, Apter G, Bergink V, Bilszta J, … Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment Consortium. (2016). The impact of education, country, race and Scale. Psychological Medicine, 21, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dias CC & Figueiredo B (2015). Breastfeeding and depression: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 171, 142–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher SD, Wisner KL, Clark CT, Sit DK, Luther JF, & Wisniewski S (2016). Factors associated with onset timing, symptoms, and severity of depression identified in the postpartum period. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203, 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford-Gilboe M, Varcoe C, Scott-Storey K, Wuest J, Case J, Currie LM, … Wathen CN (2017). A tailored online safety and health intervention for women experiencing intimate partner violence: the iCAN plan 4 safety randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health, 17, 273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghaedrahmati M, Kazemi A, Kheirabadi G, Ebrahimi A, & Bahrami M (2017). Postpartum depression risk factors: A narrative review. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 6, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, & Gray R (2009). A systematic review of studies validating the edinburgh postnatal depression scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 119, 350–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grote ND & Bledsoe SE (2007). Predicting postpartum depressive symptoms in new mothers: The role of optimism and stress frequency during pregnancy. Health & Social Work, 32, 107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatters Friedman S & Resnick PJ, (2007). Child murder by mothers: Patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry, 6, 137–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humenik ALF & Fingerhut R (2007). A pilot study assessing the relationship between child harming thoughts and postpartum depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 14, 360–366. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S, & Elmore M (1999). Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 54, 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HS, Sherman DK, & Taylor SE (2008). Culture and social support. American Psychologist, 63, 518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinsey CB, Baptiste-Roberts K, Zhu J, & Kjerulff KH (2014). Effect of previous miscarriage on depressive symptoms during subsequent pregnancy and postpartum in the first baby study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19, 391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kjerulff KH, Velott DL, Zhu J, Chuang CH, Hillemeier MM, Paul IM, & Repke JT (2013). Mode of first delivery and women’s intentions for subsequent childbearing: Findings from the first baby study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 27, 62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawley KA, Willett ZZ, Scollon CN, & Lehman BJ (2019). Did you really need to ask? Cultural variation in emotional responses to providing solicited social support. PLoS One, 14, e0219478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Long Z, Cao D, & Cao F (2017). Social support and depression across the perinatal period: A longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 2776–2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mamun AA, Clavarino AM, Najman JM, Williams GM, O’Callaghan MJ, & Bor W (2009). Maternal depression and the quality of marital relationship: A 14-year prospective study. Journal of Womens Health, 18, 2023–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Phiri K, Schaefer E, Zhu J, & Kjerulff K (2016). Trajectories of depressive symptoms throughout the peri- and postpartum period: Results from the first baby study. Journal of Womens Health, 25, 1112–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarrier K, Bushnell D, Martin M, Paczkowski R, Nelson D, & Buesching D (2011). Validation and psychometric evaluation of a 5-item measure of perceived social support. Value in Health, 14, A148. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melville JL, Gavin A, Guo Y, Fan MY, & Katon WJ (2010). Depressive disorders during pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 116, 1064–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milgrom J, Hirshler Y, Reece J, Holt C, & Gemmill AW (2019). Social support – a protective factor for depressed perinatal women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller RL, Pallant JF, & Negri LM (2006). Anxiety and stress in the postpartum: Is there more to postnatal distress than depression? BMC Psychiatry, 6, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Misra D, O’Campo P, & Strobino D (2001). Testing a sociomedical model for preterm delivery. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 15, 110–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mollard E, Hudson DB, Ford A, & Pullen C (2016). An integrative review of postpartum depression in rural U.S. communities. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 30, 418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mora PA, Bennett IM, Elo IT, Mathew L, Coyne JC, & Culhane JF (2008). Distinct trajectories of perinatal depressive symptomology: Evidence from growth mixture modeling. American Journal of Epidemiology, 169, 24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mughal MK, Giallo R, Arnold P, Benzies K, Kehler H, Bright K, & Kingston D (2018). Trajectories of maternal stress and anxiety from pregnancy to three years and child development at 3 years of age. Findings from the All Our Families (AOF) pregnancy cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 234, 318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Negron R, Martin A, Almog, Balbierz A, & Howell EA (2013). Social support during the postpartum period: Mothers’ views on needs, expectations, and mobilization of support. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17, 616–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norhayati MN, Nik Hazlina NH, Asrenee AR, & Wan Emilin WMA (2015). Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: A literature review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 34–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Hara MW & McCabe JE (2013). Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 379–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA III, Charney D, & Southwick S (2007). Social support and resilience to stress. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 4, 35–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palumbo G, Mirabella F, & Gigantesco A (2017). Positive screening and risk factors for postpartum depression. European Psychiatry, 42, 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paulson JF, Dauber S, & Leiferman JA (2006). Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics, 114, 659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, & Mullan JT (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phelan AL, DiBenedetto MR, Paul IM, Zhu J, & Kjerulff KH (2015). Psychosocial stress during first pregnancy predicts infant health outcomes in the first postnatal year. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19, 2587–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Razurel C, Bruchon-Schweitzer M, Dupanloup A, Irion O, & Epiney M (2011). Stressful events, social support and coping strategies of primiparous women during the postpartum period: A qualitative study. Midwifery, 27, 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Razurel C, Kaiser B, Antonietti JP, Epiney M, & Sellenet C (2017). Relationship between perceived perinatal stress and depressive symptoms, anxiety, and parental self-efficacy in primiparous mothers and the role of social support. Women & Health, 57, 154–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reid KM & Taylor MG (2015). Social support, stress, and maternal postpartum depression: A comparison of supportive relationships. Social Science Research, 54, 246–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, & Stewart DE (2004). Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: A synthesis of recent literature. General Hospital Psychiatry, 26, 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salehi-Pourmehr H, Mohammad-Alizadeh S, Jafarilar-Agdam N, Rafiee S, & Farshbaf-Khalili A (2018). The association between pre-pregnancy obesity and screening results of depression for all trimesters of pregnancy, postpartum and 1 year after birth: A cohort study. Journal of Perinatal Medicine, 46, 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwab-Reese LM, Schafer EJ, & Ashida S (2017). Associations of social support and stress with postpartum maternal mental health symptoms: Main effects, moderation, and mediation. Women & Health, 57, 723–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silverman ME, Reichenberg A, Savitz DA, Cnattingius S, Lichtenstein P, Hultman CM, Larsson H, & Sandin S (2017). The risk factors for postpartum depression: A population-based study. Depression and Anxiety, 34, 178–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shorey S, Chee CYI, Ng ED, Chan YH, Tam WWS, & Chong YS (2018). Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 104, 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song JE, Kim T, & Ahn JA (2015). A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for women with postpartum stress. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 44, 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tambag H, Turan Z, Tolun S, & Can R (2018). Perceived social support and depression levels of women in the postpartum period in Hatay Turkey., Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 21, 1525–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thurgood S, Avery DM, & Williamson L (2009). Postpartum depression (PPD). American Journal of Clinical Medicine, 6, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, Whiteford, & Harris MG (2017). A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 219, 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]