Abstract

The purpose of this study was to conduct a risk assessment for Clostridium perfringens foodborne illness via kimchi consumption in South Korea. Prevalence of C. perfringens in kimchi, kimchi consumption amount and frequency, and distribution conditions (time and temperature) from manufacture to the home were determined. C. perfringens initial contamination level was estimated using Beta distribution [Beta (6, 79)]. Potential C. perfringens cell counts during distribution were predicted using the Weibull model (primary models, R2 = 0.923–0.953) and a polynomial model [(δ = 1/(0.2385 + (− 0.0307 × Temp) + (0.0011 × Temp2)), R2 = 0.719]. Average daily consumption data was assessed using Gamma distribution [1.0444, 91.767, RiskShift (0.16895), RiskTruncate (0, 1078)]. The mean risk of C. perfringens-associated foodborne illness following kimchi consumption was found to be 1.21 × 10−17. These results suggest that the risk of C. perfringens foodborne illness from kimchi consumption, under current conditions, can be considered to be very low in S. Korea.

Keywords: Foodborne illness, Clostridium perfringens, Kimchi, Dose–response, @RISK simulation

Introduction

Clostridium perfringens is a gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming rod-shaped bacterium that is present in soil, rivers, and sewage, as well as in the intestines and feces of mammals, including humans (Heo et al., 2018; Labbé, 2003). C. perfringens produces toxins that are classified into five types (A, B, C, D, and E). Toxinotype A is usually associated with foodborne illnesses in humans and produces alpha toxin (CPA), with or without enterotoxin (CPE) and beta2 toxin (CPB2) (Mafart et al., 2002; Suh et al., 2013). Foodborne illness caused by C. perfringens is associated consumption of particular foods, such as ground and cooked beef, cooked kebabs, ground beef, sheep meat, ready-to-eat meats, fresh and frozen chicken, and retail chicken livers (Aras and Hadimli, 2015; Cooper et al., 2013; Golden et al., 2009; Guran et al., 2014; Kouassi et al., 2014; Nowell et al., 2010; Yibar et al., 2018). In South Korea, C. perfringens has been detected in pork, beef, chicken, and duck meats, and was associated with 155 foodborne outbreaks, affecting 6483 patients, in 2008–2018 (Hu et al., 2018; Jeong et al., 2017a; MFDS, 2018b). Furthermore, there was foodborne outbreak associated with C. perfringens due to kimchi consumption in 2008 in S. Korea (Lee et al., 2017). One hundred eighty three high school students had foodborne illness symptoms after kimchi consumption and C. perfringens was detected from them. In 2011, C. perfringens were detected in commercial napa cabbage kimchi (580 CFU/g) and diced white radish kimchi (700 CFU/g), and thus, the products contaminated with C. perfringens were banded for sale by Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) (MFDS, 2011a; 2011b).

Kimchi is composed of fermented vegetables and spices and is frequently eaten as a side dish in S. Korea (Yoon et al., 2018) and represents a potential vehicle for C. perfringens. Some kimchi is consumed before sufficient fermentation, when numbers of lactic acid bacteria are low, and this poses a particular risk for foodborne illness. There were foodborne outbreaks by kimchi consumption contaminated with other pathogens such as Escherichia coli, and E. coli foodborne illness by kimchi consumption was prevalent in S. Korea. There are various studies for detection, kinetic behavior, or risk assessment of E. coli in kimchi, however, there were insufficient studies for C. perfringens foodborne illness by kimchi consumption although there were foodborne outbreaks in S. Korea (Cho et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2018a; 2018b; MFDS, 2018a).

Microbial quantitative risk assessment (MRA) is an analytical measure for evaluating risks in foods, to manage food safety for public health, and to develop microbiological standards in accordance with international trade requirement (Lammerding, 1997). Several studies of MRA have studied for various foodborne pathogens such as C. perfringens, Salmonella, and Campylobacter in S. Korea (Jeong et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2019). A number of studies reporting risk assessments for kimchi have focused on chemical substances, such as ethyl carbamate, nitrite, nitrate, and mercury (Choi et al., 2012; Lee, 2013; Noh et al., 2006; Suh et al., 2013); however, MRA for kimchi has not been reported.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to perform an MRA for C. perfringens illness following kimchi consumption in a scenario evaluating the stages from transportation to consumption.

Materials and methods

Prevalence of C. perfringens in kimchi

Eighty-three kimchi samples (whole radish, diced radish, young radish, cucumber, napa cabbage, green onion, bean leaf, and mustard leaf) were purchased from supermarkets and traditional markets in S. Korea. Twenty-five-gram portions of the kimchi were placed into filter bags (3 M, St. Paul, MN, USA), and 225 mL buffered peptone water (BPW; BD, Sparks, MD, USA) was added. Samples were then homogenized in a pummeler (Bag mixer 400; Interscience Co., Paris, France) for 2 min. One-milliliter aliquots of the homogenates were transferred into cooked meat medium (CMM; Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK), and incubated anaerobically at 35 °C for 24 h. Then, 1 μL of the culture was streaked on tryptose sulphite cycloserine (TSC) agar (Oxoid Ltd., UK) and then incubated anaerobically at 35 °C for 24 h. Black, presumptive C. perfringens colonies on TSC agar (Oxoid Ltd., UK) plates were analyzed by PCR using primers targeting the following toxin genes: cpa, cpb, cpb2, cpe, etx, and iap (Baums et al., 2004). The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min 30 s; 35 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 1 min), elongation (55 °C for 1 min), and extension (72 °C for 1 min 20 s); and final extension at 72 °C for 2 min. The initial contamination level of C. perfringens in kimchi was determined by Beta distribution [RiskBeta (α: the number of positive samples + 1, β: the total number of samples − the number of positive samples + 1)] by application of Bayes’ Theorem to estimate the prevalence (Vose, 1997).

Selection of a representative variety of kimchi for predictive model

There are many types of kimchi, and thus, a model kimchi had to be selected for predictive models. Therefore, the following varieties were purchased from a market in Seoul, S. Korea: whole napa cabbage, sliced napa cabbage, whole white radish, diced white radish, and young radish kimchi. One hundred microliters of C. perfringens strains Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC) 5101 (type A), Korean Culture Center of Microorganisms (KCCM) 12098 (type A), KCCM40946 (type A), and KCCM40947 (type B) were inoculated into 10 mL CMM, from 20% glycerol stocks, respectively, and incubated anaerobically at 35 °C for 24 h. Then, 3 mL of the cultures were inoculated into 30 mL Duncan Strong (DS) medium (15.0 g proteose peptone, 4.0 g yeast extract, 1.0 g sodium thioglycolate, 4.0 g sodium phosphate, 10.0 g raffinose, and 50 mL 0.51 mM caffeine in 1 L distilled water), and incubated anaerobically at 35 °C for 48 h. The subcultures were then centrifuged at 1912×g and 4 °C for 15 min, and the cell pellets were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 0.2 g KCl, 0.2 g KH2PO4, 8.0 g NaCl, and 1.5 g Na2HPO4·7H2O in 1 L distilled water; pH 7.4). Cell suspensions were mixed and diluted to a final concentration of 7.5 log CFU/mL in preparation for inoculation. Kimchi samples were inoculated with 0.1 mL of this inoculum to achieve a final concentration of 4.0 log CFU/g, and the samples were stored at 20 °C for 72 h. During storage, 20-mL BPW was placed into a sample bag containing 10-g kimchi, and it was homogenized in a pummeler (Bag mixer 400; Interscience Co., France). The homogenates were serially diluted with 0.1% BPW and were spread-plated on TSC agar. The plates were then incubated anaerobically at 35 °C for 48 h, after which, typical black colonies with a halo were manually counted. C. perfringens cell counts were compared among kimchi varieties, and the variety with the best sustained survival over time was selected for use in the predictive model.

Development of predictive models

Predictive models were developed to describe the effect of temperature change on microbiological growth. Ten-gram portions of young radish kimchi were inoculated with 0.1 mL of C. perfringens inoculum to a final target concentration of 4.0 log CFU/g, and then stored at 7 °C, 15 °C, 25 °C, and 35 °C. Kimchi samples were homogenized and serially diluted as before. TSC agar was then inoculated and incubated anaerobically at 35 °C for 48 h, and the typical black colonies with halos were counted, as before. The kinetic behavior of C. perfringens was evaluated via development of a primary model with the Weibull model parameters [Log(N) = Log(N0) − (time/δ)ρ; N, cell counts; N0, initial cell counts; δ, treatment time for the first decimal reduction; ρ, curve shape parameter] (Mafart et al., 2002), and a polynomial model [Y = 1/(a + b × T + C × T2; a, b, and c, constant; T, storage temperature] was developed, using kinetic parameters (δ) to describe temperature effects. To evaluate the model performance, C. perfringens was inoculated in young radish kimchi as described above, and samples were stored at 10 °C and 23 °C. During storage, C. perfringens cell counts were enumerated, as described above, to obtain observed values. The observed values were compared to the model-predicted values, and sum of squares for error (SSE) and the root mean square error (RMSE) values were calculated to evaluate model performance (Baranyi et al., 1996).

Distribution time and temperature

Storage temperature and time data for distribution of kimchi to market, market storage, and market display were collected by personal communication. Food temperature during home storage was applied to the models in reference to the findings of Lee et al. (2015).

Consumption amount and frequency

Data describing the daily kimchi consumption amount and frequency in S. Korea were obtained from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHNES) (KCDC, 2018). The appropriate probability distribution of this data was determined using the @RISK program version 7.6 (Palisade Corp., Ithaca, NY, USA).

Hazard characteristics and risk characterization

To calculate probability of C. perfringens-associated illness/person/day, a dose–response model, developed by Golden et al. (2009), was applied to the data. A simulation model was established by compiling data on the C. perfringens prevalence and initial concentration, data from the predictive models regarding distribution time and temperature and consumption amount and frequency, and data from the dose–response model, and applying to @RISK software, with 10,000 iterations.

Statistical analysis

The δ values of the predictive (primary) models were analyzed using a general linear model (GLM) with SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Least square means (LSM) among temperature data were compared with a pairwise t test at α = 0.05.

Results and discussion

Prevalence and initial contamination of C. perfringens

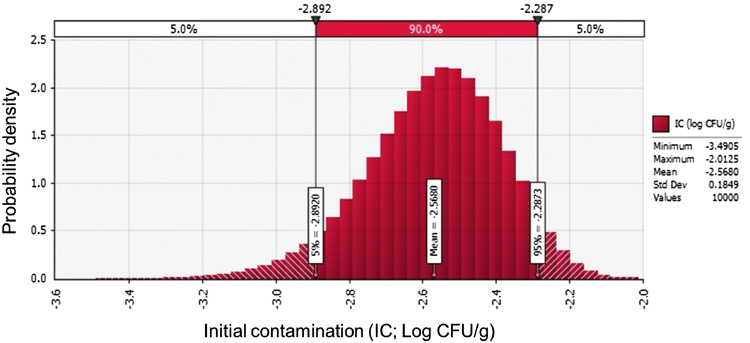

C. perfringens was detected in five kimchi samples (6%; 5/83), and thus, the initial contamination level was estimated by first describing the prevalence in the form of Beta distribution [BetaRisk (6, 79)]. Probability distribution was then assessed to determine the average initial contamination level (− 2.6 log CFU/g; Appendix).

C. perfringens predictive model

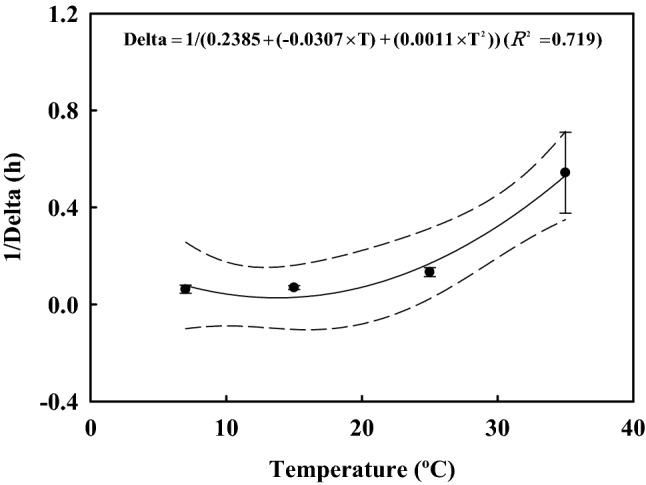

In the preliminary experiments, the young radish kimchi survived for the longest time among the several types of kimchi (young radish kimchi, whole napa cabbage kimchi, sliced napa cabbage kimchi, whole white radish kimchi, and diced white radish kimchi) (data not shown). Young radish kimchi was therefore selected as a model kimchi for development of the predictive model. Total aerobic bacterial cell counts increased during storage (data not shown); however, C. perfringens survived at early time and cell counts then decreased at later time at 7 °C (δ = 19.07), 15 °C (δ = 14.81), 25 °C (δ = 7.86), and 35 °C (δ = 2.19). The ρ values, representing the curve shape parameters, were 0.81 (7 °C), 1.23 (15 °C), 1.32 (25 °C), and 0.85 (35 °C) (Table 1). Using the primary Weibull model, R2 was calculated as 0.923 − 0.953. Secondary modeling of the δ values, where δ = 1/(0.2385 + (− 0.0307 × T) + (0.0011 × T2)), resulted in an R2 value of 0.719 (Fig. 1). Primary modelling revealed that there was no correlation between ρ parameters and temperature; therefore, secondary modelling was unnecessary. The average of the ρ values (1.05) was applied to the simulation scenario (Table 1). Model performance was evaluated by calculating RMSE, 0.637 (10 °C) and 0.547 (23 °C), which indicated that the model was appropriate for description of C. perfringens growth pattern in kimchi under different storage temperatures (Table 2). Although the R2 value for the secondary model of δ value was relatively low, the RMSE values showed that the predictive model described appropriately the kinetic behavior of C. perfringens in kimchi. In reference to Jeong et al. (2017b), the secondary model for δ value was developed with 0.616 of R2, but the model was used for predicting the fate of Campylobacter in beef tripe because of low RMSE (0.581) value.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters (δ and ρ), calculated using the Weibull model, of Clostridium perfringens in kimchi during storage at 7 °C, 15 °C, 25 °C, and 35 °C

| Temperature (°C) | Kinetic parameters | R2 | SSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ | ρ | |||

| 7 | 19.07 ± 9.94C | 0.81 ± 0.25A | 0.953 ± 0.019 | 2.727 ± 0.945 |

| 15 | 14.81 ± 2.73BC | 1.23 ± 0.34A | 0.930 ± 0.024 | 4.060 ± 1.618 |

| 25 | 7.86 ± 2.17AB | 1.32 ± 0.14A | 0.932 ± 0.015 | 3.049 ± 0.547 |

| 35 | 2.19 ± 1.02A | 0.85 ± 0.24A | 0.923 ± 0.051 | 4.507 ± 3.685 |

Values are mean ± SD. δ, treatment time for the first decimal reduction; ρ, curve shape parameter; SSE, sum of squared error

Values followed by different letters in a column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Fig. 1.

The δ values (treatment time for the first decimal reduction) from the primary models and fitted line developed by the secondary model as a function of temperature for Clostridium perfringens in young radish kimchi

Table 2.

Clostridium perfringens cell counts (observed values) during storage at 10 °C and 23 °C, cell counts (predicted values) calculated from the models, and the root mean square error (RMSE) values for evaluating the primary model (Weibull model) performance

| Temperature (°C) | Time (h) | Observed value | Predicted value | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 4.5 | |

| 6 | 4.7 ± 0.0 | 4.3 | ||

| 9 | 4.1 ± 0.0 | 4.1 | ||

| 12 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 4.0 | 0.637 | |

| 24 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.5 | ||

| 48 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 2.4 | ||

| 96 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.2 | ||

| 23 | 0 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 4.5 | |

| 3 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.2 | ||

| 6 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 3.8 | ||

| 8 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.6 | 0.547 | |

| 9 | 3.8 ± 0.0 | 3.5 | ||

| 12 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 3.1 | ||

| 24 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 | ||

| 30 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.9 |

Storage time and temperature

The time taken for market transportation was determined by personal communication at the market. The kimchi products were transported to the market within either 3 h, 4 h, or 6 h of manufacturing; therefore, Pert distribution was selected for analysis, with the following parameters: (3, 4, 6). Temperature during market transportation was measured in person, in co-operation with a major market in S. Korea. The temperature values were fitted using @RISK, where Weibull distribution was used to describe this data [1.3219, 2.8404, RiskShift (3.1093), RiskTruncate (1, 40)]. Market storage time and temperature were determined by personal communication at the market. After transportation to the market, kimchi was stored at 0 − 10 °C for 0.1667 − 0.5 h, and thus, Uniform distribution was fitted with parameters (0, 10) and (0.1667, 0.5), respectively. Kimchi was displayed at the market for 0 − 720 h (mean, 240 h), and thus, Pert distribution was fitted with the following parameters: (0, 240, 720). The temperature of market display was measured, and the minimum (1.0682 °C) and maximum (11.732 °C) temperatures were fitted using Uniform distribution, with the following parameters: (1.0682, 11.732). The kimchi was consumed within 720 h (shelf life), and thus, the data for home storage was fitted to Uniform distribution with the following parameters: (0, 720). The temperature of kimchi at home was applied as Loglogistic distribution [− 29.283, 33.227, 26.666, RiskTruncate (− 5, 20)] in reference to the temperature of home refrigerators as defined by Lee et al. (2015) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Simulation model and formulas used to calculate the risk of Clostridium perfringens foodborne illness following consumption of kimchi at home; prepared using @RISK version 7.6

| Input model | Variable | Formula | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product | |||

| Pathogen contamination level | |||

| C. perfringens prevalence | PR | = RiskBeta(6,79) | This research, Sanaa et al. (2004), Vose (1997) |

| Initial contamination level (log CFU/g) | C | = −LN(1 − PR)/25g | Sanaa et al. (2004) |

| IC | = log(C) | ||

| Market | |||

| Market transportation | |||

| Transportation time (h) | TimeMark-trans | = RiskPert(3,4,6) | Personal communicationa |

| Temperature during transportation (°C) | TempMark-trans | = RiskWeibull(1.3219,2.8404,RiskShift(3.1093),RiskTruncate(1,40)) | Personal communication |

| Death | |||

| Treatment time for the first decimal reduction | δ | = 1/(0.2385 − 0.0307 × TempMark-trans + 0.0011 × TempMark-2trans)) | This research |

| Curve shape parameter | ρ | Fixed 1.05 | This research |

| Contamination level before market storage (log CFU/g) | C1 | = IC − (TimeMark-trans/δ)ρ | Mafart et al. (2002) |

| Market storage | |||

| Storage time at market (h) | TimeMark-st | = RiskUniform(0.1667,0.5) | Personal communication |

| Storage temperature at market (°C) | TempMark-st | = RiskUniform(0,10) | Personal communication |

| Death | |||

| Treatment time for the first decimal reduction | δ | = 1/(0.2385 − 0.0307 × TempMark-st + 0.0011 × TempMark-2st)) | This research |

| Curve shape parameter | ρ | Fixed 1.05 | This research |

| Contamination level before market display (log CFU/g) | C2 | = C1 − (TimeMark-st/δ)ρ | Mafart et al. (2002) |

| Market display | |||

| Display time (h) | TimeMark-dis | = RiskPert(0,240,720) | Personal communication |

| Display temperature in market (°C) | TempMark-dis | = RiskUniform(1.0682,11.732) | Personal communication |

| Death | |||

| Treatment time for the first decimal reduction | δ | = 1/(0.2385–0.0307 × TempMark-dis + 0.0011 × Temp2Mark-dis)) | This research |

| Curve shape parameter | ρ | Fixed 1.05 | This research |

| Contamination level before home (log CFU/g) | C3 | = C2 − (TimeMark-dis/δ)ρ | Mafart et al. (2002) |

| Home | |||

| Home storage | |||

| Storage time at home (h) | TimeHome-st | = RiskUniform(0,720) | This research |

| Storage temperature at home (°C) | TempHome-st | = RiskLogLogistic(− 29.283,33.227,26.666,RiskTruncate(− 5,20)) | Lee et al. (2015) |

| Death | |||

| Treatment time for the first decimal reduction | δ | = 1/(0.2385 − 0.0307 × TimeHome-st + 0.0011 × Time2Home-st)) | This research |

| Curve shape parameter | ρ | Fixed 1.05 | This research |

| Contamination level before consumption (log CFU/g) | C4 | = C3 − (TimeHome-st/δ)ρ | Mafart et al. (2002) |

| Consumption | |||

| Daily consumption average amount (g) | Consump | = RiskGamma(1.0444,91.767,RiskShift(0.16895),RiskTruncate(0,1078)) | KCDC (2018) |

| Daily consumption frequency (%) | ConFre | Fixed 76.0 | KCDC (2018) |

| Daily non-consumption frequency (rate) | CF (0) | = 1 − 76.0/100 | KCDC (2018) |

| Daily consumption frequency (rate) | CF (1) | = 76.0/100 | KCDC (2018) |

| Distribution for consumption frequency | CF | = RiskDiscrete({0,1},{CF(0),CF(1)}) | KCDC (2018) |

| Daily consumption average amount considered frequency | Amount | = IF(CF=0,0,Consump) | KCDC (2018) |

| Dose–response | |||

| C. perfringens amount (CFU) | N | = 10C4 × Amount | |

| Parameter | r | Fixed 1.82 × 10−11 | Golden et al. (2009) |

| Risk | |||

| Probability of illness/person/day | Risk | = 1 − exp(− r × N) | Golden et al. (2009) |

aPersonal communication with manager in charge of products at the market

Kimchi consumption in S. Korea

According to the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHNES) (KCDC, 2018), daily average consumption amount of kimchi with no additional heating was 96.0 g, with a consumption frequency of 76.0% in S. Korea. This indicates that most people in S. Korea consume kimchi daily. Gamma distribution [1.0444, 91.767, RiskShift (0.16895), RiskTruncate (0, 1078)] was determined to be optimal when fitting this data using the @RISK program.

Dose–response model

The probability of C. perfringens foodborne illness following consumption of kimchi was estimated using the exponential dose–response model [1 − exp (− r × N), r = 1.82 × 10−11] (Golden et al., 2009), where N is the number of viable C. perfringens consumed, and r (fixed value) is the probability of single cell of C. perfringens causing foodborne illness. N (CFU) is calculated as C. perfringens cell counts (CFU/g) × consumption amount (g), where viable CFU/g were calculated from initial contamination level to home storage, accounting for the impact of storage time and temperature at distribution, market storage and display, and home storage. C. perfringens cell counts were calculated, using the developed predictive model responding to the condition as described above (Table 3).

Simulation and risk characterization

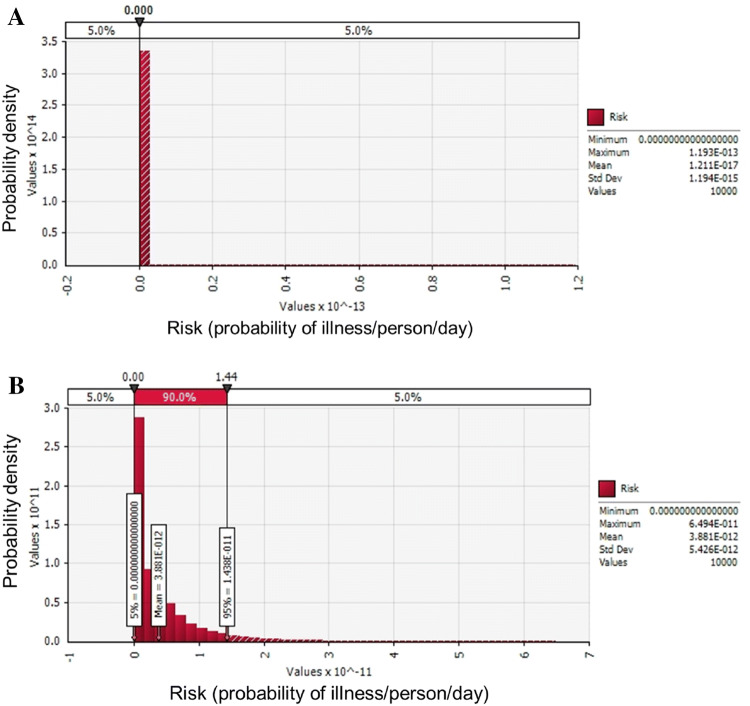

The simulation model was applied for a scenario from a market to consumption at home. The scenario was composed of Product, Market (transportation, storage, and display), Home, Consumption (daily consumption average amount and consumption frequency), Dose–response, and Risk input models, as presented in Table 3. The initial contamination level was applied to the developed predictive models from Market to Home accounting for the time and temperature of each environment. The final contamination level before consumption (log CFU/g) was applied to Consumption and Dose–response calculations, and then probability of illness per person per day was calculated. The average C. perfringens contamination level in kimchi was estimated as − 2.6 log CFU/g at the stage of initial contamination (IC), and then decreased continuously to the stage of home storage (C4). The mean probability of illness/person/day following home consumption was very low, at 1.21 × 10−17 (Fig. 2A). Consumption immediately after manufacturing (IC) is associated with a mean risk (probability of illness/person/day) of 3.88 × 10−12 (Fig. 2B). In comparison with the probability of C. perfringens foodborne illness of ham and sausage (3.97 × 10−11 ± 1.80 × 10−9) (Ko et al., 2012), natural (9.57 × 10−14) and processed cheese (3.58 × 10−14) (Lee et al., 2016), and the probability of Campylobacter jejuni foodborne illness by consuming ground meat (5.68 × 10−10) per person per day in Korea (Lee et al., 2019), the risk of C. perfringens foodborne illness of kimchi can be considered to be relatively low or similar. The low risk of C. perfringens foodborne illness may be caused by decrease in C. perfringens cell counts during distribution and storage as shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. In conclusion, this quantitative risk assessment of C. perfringens-associated illness via kimchi consumption represents a useful method for estimation of C. perfringens foodborne illnesses in S. Korea, and the results show that the risk of C. perfringens-associated illness from kimchi consumption is very low.

Fig. 2.

Risk (probability of illness/person/day) of Clostridium perfringens foodborne illness when kimchi is consumed at home after purchasing at a market (A) and when consumed immediately after manufacturing (B)

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Grant (17162MFDS035) from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2018.

Appendix

See Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Beta distribution of the initial contamination level (IC) of Clostridium perfringens in kimchi, fitted with @RISK version 7.6

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None of the authors of this study has any financial interest or conflict with industries or parties.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yukyung Choi, Email: lab_yukyung@naver.com.

Joohyun Kang, Email: diana_22@naver.com.

Yewon Lee, Email: yw0322@naver.com.

Yeongeun Seo, Email: sye0360@naver.com.

Heeyoung Lee, Email: hylee06@kfri.re.kr.

Sejeong Kim, Email: 3337119@hanmail.net.

Jeeyeon Lee, Email: fmjylee02@naver.com.

Jimyeong Ha, Email: hayan29@naver.com.

Hyemin Oh, Email: odry0731@naver.com.

Yujin Kim, Email: yujinkim77@gmail.com.

Kye-Hwan Byun, Email: kyehwan-byun@naver.com.

Sang-Do Ha, Email: sangdoha@cau.ac.kr.

Yohan Yoon, Email: yyoon@sm.ac.kr.

References

- Aras Z, Hadimli HH. Detection and molecular typing of Clostridium perfringens isolates from beef, chicken and turkey meats. Anaerobe. 2015;32:15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranyi J, Ross T, McMeekin TA, Roberts TA. Effects of parameterization on the performance of empirical models used in ‘predictive microbiology’. Food Microbiol. 1996;13:83–91. doi: 10.1006/fmic.1996.0011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baums CG, Schotte U, Amtsberg G, Goethe R. Diagnostic multiplex PCR for toxin genotyping of Clostridium perfringens isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 2004;100:11–16. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(03)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SH, Kim J, Oh KH, Hu JK, Seo J, Oh SS, Hur MJ, Choi YH, Youn SK, Chung GT, Choe YJ. Outbreak of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O169 enteritis in schoolchildren associated with consumption of kimchi, Republic of Korea, 2012. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014;142:616–623. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Park SK, Kim MH. Risk assessment of mercury through food intake for Korean population. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012;44:106–113. doi: 10.9721/KJFST.2012.44.1.106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Lee S, Kim HJ, Lee H, Kim S, Lee J, Ha J, Oh H, Choi KH, Yoon Y. Pathogenic Escherichia coli and Salmonella can survive in kimchi during fermentation. J. Food Prot. 2018;81:942–946. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-17-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Lee S, Kim HJ, Lee H, Kim S, Lee J, Ha J, Oh H, Yoon JW, Yoon Y, Choi KH. Serotyping and genotyping characterization of pathogenic Escherichia coli strains in kimchi and determination of their kinetic behavior in cabbage kimchi during fermentation. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2018;15:420–427. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2017.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper KK, Bueschel DM, Songer JG. Presence of Clostridium perfringens in retail chicken livers. Anaerobe. 2013;21:67–68. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden NJ, Crouch EA, Latmer H, Kadrt AR, Kause J. Risk assessment for Clostridium perfringens in ready-to-eat and partially cooked meat and poultry products. J. Food Prot. 2009;72:1376–1384. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-72.7.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guran HS, Vural A, Erkan ME. The prevalence and molecular typing of Clostridium perfringens in ground beef and sheep meats. J. Verbrauch. Lebensm. 2014;9:121–128. doi: 10.1007/s00003-014-0866-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heo S, Kim MG, Kwon M, Lee HS, Kim GB. Inhibition of Clostridium perfringens using bacteriophages and bacteriocin producing strains. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2018;38:88–98. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2018.38.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WS, Kim H, Koo OK. Molecular genotyping, biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens isolated from meat supplied to school cafeterias in South Korea. Anaerobe. 2018;52:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong D, Kim DH, Kang IB, Chon JW, Kim H, Om AS, Lee JY, Moon JS, Oh DH, Seo KH. Prevalence and toxin type of Clostridium perfringens in beef from four different types of meat markets in Seoul. Korea. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017;26:545–548. doi: 10.1007/s10068-017-0075-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Chon JW, Kim H, Song KY, Seo KH. Risk assessment for salmonellosis in chicken in South Korea: The effect of Salmonella concentration in chicken at retail. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2018;38:1043–1054. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2018.e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Lee J, Lee H, Lee S, Kim S, Ha J, Yoon K, Yoon Y. Quantitative microbial risk assessment for Campylobacter foodborne illness in raw beef offal consumption in South Korea. J. Food Prot. 2017;80:609–618. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KCDC (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHNES). Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/sub03/sub03_02_02.do. Accessed May 12, 2019. (2018)

- Ko EK, Moon JS, Wee SH, Bahk GJ. Quantitative microbial risk assessment of Clostridium perfringens on ham and sausage products in Korea. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2012;32:118–124. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2012.32.1.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kouassi KA, Dadie AT, N’Guessan KF, Dje KM, Loukou YG. Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium difficile in cooked beef sold in côte d’ivoire and their antimicrobial susceptibility. Anaerobe. 2014;28:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbé RG. Occurrence of Clostridium perfringens. Encyclopedia of food sciences and nutrition. 2nd ed. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, USA. pp. 1398-1401 (2003)

- Lammerding AM. An overview of microbial food safety risk assessment. J. Food Prot. 1997;60:1420–1425. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-60.11.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Kim K, Choi KH, Yoon Y. Quantitative microbial risk assessment for Staphylococcus aureus in natural and processed cheese in Korea. J. Dairy Sci. 2015;98:5931–5945. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-9611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Lee S, Kim S, Lee J, Ha J, Yoon Y. Quantitative microbial risk assessment for Clostridium perfringens in natural and processed cheeses. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2016;29:1188–1196. doi: 10.5713/ajas.15.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Yoon SR, Kim SJ, Lee HM, Lee JY, Lee JH, Kim SH, Ha JH. Identification of microbial communities, with a focus on foodborne pathogens, during kimchi manufacturing process using culture-independent and-dependent analyses. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017;81:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Lee H, Lee S, Kim S, Ha J, Choi Y, Oh H, Kim Y, Lee Y, Yoon K, Seo K, Yoon Y. Quantitative microbial risk assessment for Campylobacter jejuni in ground meat products in Korea. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2019;39:565–575. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2019.e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KG. Analysis and risk assessment of ethyl carbamate in various fermented foods. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013;236:891–898. doi: 10.1007/s00217-013-1953-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mafart P, Couvert O, Gaillard S, Leguérinel I. On calculating sterility in thermal preservation methods: application of the Weibull frequency distribution model. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002;72:107–113. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MFDS (Ministry of Food and Drug Safety) Characteristics and risk assessment of anti-acidic pathogenic E. coli in kimchi. DOI: 10.23000/TRKO201900003437. (2018a)

- MFDS (Ministry of Food and Drug Safety). Foodborne disease outbreak. Available from: https://www.foodsafetykorea.go.kr/portal/healthyfoodlife/foodPoisoningStat.do. Accessed Feb. 22, 2019. (2018b)

- MFDS (Ministry of Food and Drug Safety). Press release (2011. 11. 17.). Available from: http://116.67.34.204/user/is/srvcinfo/MoreViewSearchBbsList2.do;jsessionid=Cgg5qkpo4wB2eSmmDtnLf5UbP6N40d2GzNafjFWAhS5wbAHa4rH6vaBays5uxRO2.csmwas1_servlet_engine1?commSearchKeyword=회수&searchSortType=1&searchType=§ion=00000348. Accessed Jan. 21, 2020. (2011a)

- MFDS (Ministry of Food and Drug Safety). Press release (2011. 11. 18.). Available from: http://116.67.34.204/user/is/srvcinfo/MoreViewSearchBbsList2.do;jsessionid=Cgg5qkpo4wB2eSmmDtnLf5UbP6N40d2GzNafjFWAhS5wbAHa4rH6vaBays5uxRO2.csmwas1_servlet_engine1?commSearchKeyword=회수&searchSortType=1&searchType=§ion=00000348. Accessed Jan. 21, 2020. (2011b)

- Noh IW, Ha MS, Han EM, Jang IS, An YJ, Ha SD, Park SK, Bae DH. Assessment of the human risk by an intake of ethyl carbamate present in major Korean fermented foods. J. Microbiol. Biotechn. 2006;16:1961–1967. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell VJ, Poppe C, Parreira VR, Jiang YF, Reid-Smith R, Prescott JF. Clostridium perfringens in retail chicken. Anaerobe. 2010;16:314–315. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanaa M, Coroller L, Cerf O. Risk assessment of listeriosis linked to the consumption of two soft cheeses made from raw milk: Camembert of normandy and brie of meaux. Risk Anal. 2004;24:389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh J, Paek OJ, Kang Y, Ahn JE, Jung JS, An YS, Park SH, Lee SJ, Lee KH. Risk assessment on nitrate and nitrite in vegetables available in Korean diet. J. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2013;56:205–211. doi: 10.3839/jabc.2013.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vose DJ. Risk analysis in relation to the importation and exportation of animal products. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz. 1997;16:17–29. doi: 10.20506/rst.16.1.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yibar A, Cetin E, Ata Z, Erkose E, Tayar M. Clostridium perfringens contamination in retail meat and meat-based products in Bursa. Turkey. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2018;15:239–245. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2017.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JY, Kim D, Kim EB, Lee SK, Lee M, Jang A. Quality and lactic acid bacteria diversity of pork salami containing kimchi powder. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2018;38:912–926. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2018.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]