Abstract

The current study examined anxiety and distress among members of the first community to be quarantined in the USA due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to being historically significant, the current sample was unusual in that those quarantined were all members of a Modern Orthodox Jewish community and were connected via religious institutions at which exposure may have occurred. We sought to explore the community and religious factors unique to this sample, as they relate to the psychological and public health impact of quarantine. Community organizations were trusted more than any other source of COVID-19-related information, including federal, state and other government agencies, including the CDC, WHO and media news sources. This was supported qualitatively with open-ended responses in which participants described the range of supports organized by community organizations. These included tangible needs (i.e., food delivery), social support, virtual religious services, and dissemination of COVID-19-related information. The overall levels of distress and anxiety were elevated and directly associated with what was reported to be largely inadequate and inconsistent health-related information received from local departments of health. In addition, the majority of participants felt that perception of or concern about future stigma related to a COVID-19 diagnosis or association of COVID-19 with the Jewish community was high and also significantly predicted distress and anxiety. The current study demonstrates the ways in which religious institutions can play a vital role in promoting the well-being of their constituents. During this unprecedented pandemic, public health authorities have an opportunity to form partnerships with religious institutions in the common interests of promoting health, relaying accurate information and supporting the psychosocial needs of community members, as well as protecting communities against stigma and discrimination.

Keywords: COVID-19, Religion, Public health, Stigma, Distress

Introduction

In early March, the novel coronavirus remained a distant threat to most Americans. Despite pockets of outbreak in Seattle, confirmed cases in California, and mounting cases throughout Europe, most people in the United States felt that the possibility of infection was remote. On March 2, the first community-acquired case of COVID-19 was confirmed in New York State. A resident of lower Westchester county, the identification of “Patient-one” was a historic and life-altering event for many. Quickly following the diagnosis, the first large-scale quarantine order in the USA in over a century was ordered and included anyone who may have been in contact with Patient-one or his family members. What resulted was the quarantine of portions of lower Westchester county and the Northwest Bronx. While not geographically adjacent, these areas in fact represented a tight-knit community connected through religious and educational institutions. Patient-one is a member of the Modern Orthodox Jewish community, and quarantine directives were ordered for anyone that attended services or life-cycle events at the individual’s synagogue the previous weekend. In addition, all students, staff and faculty at the school attended by the individual’s children, a large Modern Orthodox day school in the New York City serving communities in the Bronx, Westchester, Manhattan and lower Connecticut, were also quarantined. The result was the isolation of virtually an entire community ranging from toddlers to adults connected via their adherence to a particular religious tradition and affiliation with the institutions associated with it. In addition, it emerged that Jews, and specifically the Orthodox community in New York, was one of the first and most heavily impacted communities in the COVID-19 crisis due to its emphasis on the centrality of communal religious life.

It has become evident over the course of the COVID-19 crisis that surprisingly little is known about the psychological impacts of quarantine. Studies from previous epidemics have relied on retrospective recall post-quarantine (Brooks et al. 2020; Hawryluck et al. 2004; Mazumder et al. 2020). Research from the SARS (Gardner and Moallef 2015; Hawryluck et al. 2004), Ebola (Drazen et al. 2014) and MERS (Jeong et al. 2016) epidemics have found elevated levels of distress, anxiety and depression both immediately following and months after quarantine had ended. The current study is among the first to approach the psychological impact of quarantine while individuals are actively under a quarantine directive. We sought to sample members of this first community to be quarantined in the USA to assess levels of distress and anxiety and to understand psychosocial factors specific to this community. We previously reported (Rosen et al. 2020) that levels of both anxiety and distress were elevated in this sample, and we examined situational and behavioral factors predictive of anxiety. In addition to situational factors such as length of time in quarantine and family composition, we found that behavioral factors including excess time engaged with COVID-19-related media and poor sleep quality were directly related to increased distress.

The current paper seeks to explore factors that are unique to this sample and community. We propose that a variety of factors unique to the religious nature of the community and associated institutions have the potential to mitigate or exacerbate levels of observed distress and anxiety. Specifically, we explore the ways in which this community, as both the first one in the USA with known widespread transmission and one with a highly visible religious identity, experiences stigma in relation to COVID-19 and the extent to which that impacts distress/anxiety. Feeling stigmatized could be a result of a variety of factors. In the early days of the pandemic in New York City, simply receiving a diagnosis of COVID-19 was likely perceived as stigmatizing as the extent of infection was not yet apparent. Additionally, since at that time it appeared that the infection was spreading through this one particular religious community, it likely enhanced feelings of stigmatization on a community and/or individual level.

Additionally, we examine the ways in which the clarity of health information is related to distress/anxiety and how religious institutions play a role in conveying COVID-19-related information, which in turn may mitigate the psychological impacts of quarantine. We also explore ways in which community institutions functioned as a support system during the earliest weeks of the pandemic. Previous research has recognized the importance of religious institutions, and specifically the role of religious leaders, in promoting health and communicating health messages through credibility in their communal positions and knowledge of their constituents (Anshel and Smith 2014; Taylor et al. 2019). To our knowledge, however, this type of dissemination has not been directly compared to messages delivered through public health authorities and has certainly not been examined in the midst of a global pandemic.

By being the first quarantined community in New York, and among the very first in the USA, this community is one of historical significance. The scope of this quarantine was determined not by proximity but by community, and the ties which bind this community together may have protective effects as well as additional risks associated with it. The fact that this community is inherently connected through both religious beliefs and institutions provides a unique opportunity to explore how individual and communal aspects of religious life may impact the psychological response to large-scale crises.

Methods

Sample Recruitment

Invitations to participate in an online, anonymous study were distributed to quarantined community members via daily e-mails sent from affiliated religious community organizations (i.e., schools and synagogues). Data were collected between March 15 and March 17, 2020, while participants were in varying stages of quarantine and before widespread shelter-in-place orders were issued for the rest of the state and country. The study was distributed to approximately 1250 individuals. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Measures

Demographics

Basic demographic factors were assessed including, age, gender and family composition. [For a complete list of demographic factors and other general predictors of anxiety and distress, see Rosen et al. (2020).]

Religious Commitment

Participants were asked to rate the importance of religion to them using a simple question that asked “Generally speaking how important is religion to you?” Response options included “1—center of my entire life,” “2—very important,” “3—moderately important,” “4—not important at all, though I am religious” and “5—I am not religious.” Using a question of this nature has been shown to be an efficient and valid measure of religiosity-associated experiences (Kirkpatrick and Hood 1990).

Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) (Tanner 2012)

Distress was measured using the Subjective Units of Distress Scale. The SUDS is one of the most widely used clinical tools to measure overall distress in the current moment. Respondents are asked to rate their levels of anxiety on a scale of 0–100, with response options ranging from “0” = totally relaxed to “100” = highest distress/fear/anxiety/discomfort that you have ever felt. Ratings above 40 are generally considered elevated, and ratings above 60 are thought to reflect moderate to severe levels of distress.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck et al. 1988)

Anxiety was measured using the Beck Anxiety Inventory, one of the most widely used measures of anxiety. The BAI asks about the extent of anxiety symptoms over the last 7 days and includes items which ask about the cognitive aspect of anxiety as well as the somatic aspects of anxiety. Cognitive items include feeling “scared,” “fear of losing control” and feeling “terrified.” Somatic items include feeling “dizzy or lightheaded,” feeling “shaky/unsteady” and “difficulty breathing.” Because items on the somatic factor extensively overlap with the symptoms of COVID-19, only items on the cognitive factor were used. In addition, because the constructs of overall distress and general anxiety are overlapping, the term distress/anxiety will be used throughout the paper.

Stigma

Participants were asked about the extent to which they felt or expected to feel stigmatized due to their exposure/potential exposure to COVID-19. Response options included “No,” “Yes, I/my family have felt stigmatized,” “Yes, members of our community have already felt stigmatized” and “I/We anticipate being stigmatized.” Feeling stigmatized could be a result of a variety of factors. Subsequently, participants that answered “yes” were invited to elaborate on their experience in an open-ended follow-up question.

Trust in Informational Sources

Participants were asked about the extent to which they trusted or felt confidence in the COVID-19-related information received from the following sources: “local community organizations (e.g., school or synagogue),” “State Government,” “Federal Government,” “Local Department of Health (e.g., NYC or Westchester),” “Centers for Disease Control (CDC),” “World Health Organization,” “News Media,” “Social Media” and “Foreign Governments.” Response options ranged from “1—I do not trust at all” to “4—I completely trust.”

Participants were also asked specifically about the information they received directly pertaining to guidelines for quarantine and were asked, “How would you rate the clarity of the information you have received from government agencies regarding the parameters of self-quarantine?” Response options included “1—completely inadequate,” “2—somewhat adequate but with significant gaps,” “3—more or less adequate but I could use more information,” “4—adequate” and “5—clear and informative.”

Open-Ended Questions

Participants were given the opportunity to elaborate on their experiences further in two open-ended response questions. The first pertained to the response of community organizations and asked, “Are there any actions your community has taken to help cope with quarantine?” Participants were also asked to elaborate on their experience of stigma and were asked, “What kind of stigma have you experienced or are concerned about?”

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 303 individuals completed the survey. The mean age was 43 years (SD = 14.8) and ranged from 18 to 95 years. More than half (68.2%) of respondents were female, and 89.2% of respondents had a 4-year college degree or higher. [For a complete list of demographics, see Rosen et al. (2020).] Overall, participants endorsed a very high level of religious commitment with 25.7% reporting that “religion is the center of my life,” 56.8% reported that religion was “very important,” 12.2% reported that it was “moderately important,” 1.0% reported that it was “not important,” and 4.4% reported that they were “not religious.”

Distress and Anxiety

As previously reported, distress and anxiety levels were significantly elevated as measured by the SUDS and the cognitive factor of the BAI. In addition, these constructs were highly correlated (r = .41, p < .001), which was expected given the well-established overlap between general distress and anxiety. Below, we explore additional variables related to distress/anxiety in an effort to elucidate how concepts related specifically to the religious quality of this sample can help us understand the experience of this unique community.

Religious Commitment

Level of religious commitment was not significantly associated with either distress (p > .05) as measured by the SUDS, or anxiety (p > .05) as measured by the BAI cognitive factor. Given the extremely high level of religious commitment of the sample, this lack of association is likely a result of this limited variability. Implications for further exploring this relationship are discussed later.

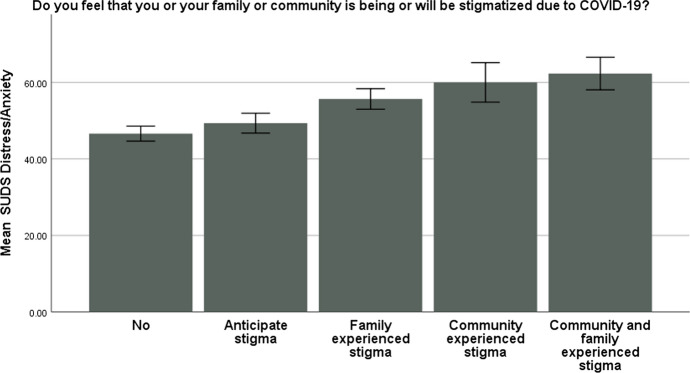

Stigma

With regard to feeling stigmatized, 49.8% of the sample reported that they had not experienced any form of stigma as a result of quarantine or exposure to COVID-19, and 50.2% of the sample reported stigma-related concern. 18.6% of the sample reported that they anticipate being stigmatized, 22.2% reported that they or their family have already experienced stigma, 4.6% reported that they believe that their community has been stigmatized, and 4.9% reported that both their family and larger community have experienced stigma. The extent to which one experienced feeling stigmatized significantly predicted level of anxiety on the SUDS (B = 1.086, p < .001) and the BAI cognitive factor (B = .295, p = .003) with a greater level of feeling stigmatized associated with greater levels of anxiety (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Association of distress as measured by the SUDS, and extent to which one has experienced stigma

Participants were invited to elaborate on their experience relating to stigma in an open-ended response question. 36.79% of responses were about general COVID-19-related stigma and 63.20% of responses related specifically to fears of or experiences of anti-Semitism. Comments related to general COVID-19-related stigma included “I felt stigmatized at work by a few colleagues who know that my children and their school were quarantined and didn’t understand why I was allowed to come to work,” “people in our apartment building are nervous about the connection to our children’s school” and “It seems something people are being judged for currently.”

Comments relating to anti-Semitism include, “Concern that the Jewish community will be held responsible for spreading COVID-19 in the New York City area,” “People blaming the Jews, have been seeing it on social media” and “That Jews [are the one’s] that brought this to the USA.” Perhaps most disturbingly, there were several participants who reported that a woman from their community had been physically assaulted and accused of spreading COVID-19 as a member of the Jewish community. Some of these included “A friend was assaulted at the store last week for being Jewish,” “Friend punched in stomach for being Jewish at a smoothie store in early days of outbreak” and “Woman in our community was punched hard in the stomach by a woman who inquired if there were any Jews in the store before choosing to walk in, and aggressively attacked our community member when she answered that she is a Jew.”

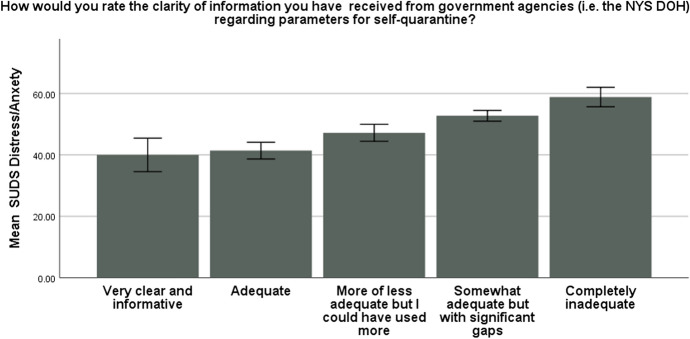

Trust in Information Sources

Participants were asked to rate the quality of the information they received from local departments of health regarding instructions for quarantine (either New York State or New York City). 20.3% of participants responded “totally inadequate,” 41.4% responded “somewhat adequate but with significant gaps,” 17.4% responded “more or less adequate but would have liked more information,” 15.7% responded “adequate,” and only 5.2% responded “clear and informative.” Notably, the extent to which participants felt well informed by the DOH was negatively associated with distress on the SUDS (r = − .29, p < .001), whereby feeling less informed was associated with higher levels of distress (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Association of distress as measured by the SUDS, and clarity of health-related information

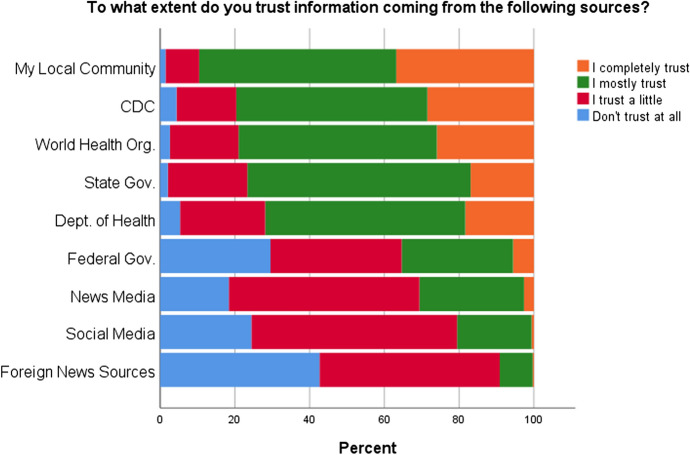

A follow-up question asked participants about the extent to which they trusted the information coming from the following sources: Their local organizations (e.g., schools and synagogues), State Government, Federal Government, DOH, WHO, CDC, News Media, and Social Media. As shown in Fig. 3, more participants responded that they “completely trusted” their local community organizations than any other information source, though they were likely to report that they “mostly trusted” state government, and the CDC as well. They were least likely to report trusting information coming from the Federal Government. In fact, as evidenced by open-ended responses, local community organizations were a primary source of COVID-related information in the earliest days of the pandemic.

Fig. 3.

Level of trust in local community organizations and government agencies

Community Supports

80.6% of participants reported that their community has taken action or set up volunteer networks to help with quarantine. An open-ended follow-up question asked them to elaborate on the types of community activities that have been most common or helpful. Responses were generally organized around a variety of different support measures set up by the community which included the following: tangible support including delivering of food and running errands, social support which included providing classes and support groups, informational support and religious support.

Tangible support 40.6% of responses referenced the community volunteer system for ensuring that those in quarantine had their basic needs met with a focus on grocery shopping, food delivery and other errands. Responses included “Extensive volunteer system for delivering food,” “WhatsApp groups for food delivery and other errands,” “Synagogue offers young members [that are not quarantined] to deliver food to older or susceptible individuals” and “People can sign up to request certain needs and others will sign up to fill those needs.”

Social support 25% of responses referenced the ways in which the community organizations have provided virtual means of social support. Notably, this also included a subset of responses that specifically referred to ensuring the well-being of elderly constituents. Responses included “support Zoom meetings, calling elderly to check in on them,” “Synagogue and school Zoom meetings to help relieve stress and allow for social interactions. The community is trying to keep us connected and as busy as possible which has been a huge help!,” “Synagogue volunteer outreach to seniors in the community” and “FaceTime classes to raise spirits.”

Informational support 18.75% of responses focused on the importance of their community organizations helping them stay informed during quarantine. Responses included “Our synagogue has been amazing at organizing information calls and hotlines” and “The school has been amazing at keeping us informed every step of the way.”

Religious and other communal supports 12.5% of responses referred to virtual opportunities to remain engaged in religious communal life and included “many zoom support, prayer and study groups,” “remote participation in shul (synagogue) classes, prayers and events” and “my synagogue is doing an outstanding job with community engagement in the time of corona.”

Discussion

The above results paint a picture of some of the more unique aspects of the first community quarantined in the USA due to COVID-19. This community was quarantined prior to when widespread stay-at-home orders were issued and were among the first, and still one of the only communities, to have their movements totally restricted. As a community bound together by their religious beliefs and quarantined due to their affiliations with Jewish community organizations at which they could have been exposed to COVID-19, we sought to explore the ways in which this identity impacted individuals’ experiences. Specifically, we examined the ways in which religious institutions and their leaders responded to the community’s needs by mobilizing support services ranging from the tangible (i.e., delivering food to those quarantined, providing information and updates about the crisis), to the spiritual (i.e., organizing virtual religious services), and how this impacted distress and anxiety.

Community Response

We explored the extent to which health-related communications impacted distress/anxiety. The earliest days of the pandemic were filled with confusion and uncertainty. Before widespread community transmission of COVID-19 was recognized, shelter-in-place and quarantine measures were not yet the norm, and there were widespread inconsistencies, even between state and city agencies, about who should be quarantined and what the parameters for quarantine should be. The lack of coordination and inconsistencies in messaging from different authorities were both a source of distress and driver of anxiety. As we observed, only 20% of the current sample found the information they received from local agencies to be adequate, while more than half (60%) reported that they found the clarity of information either completely inadequate or with significant gaps. Participants who perceived the messages to be inadequate also reported higher levels of distress. It is on this front that local religious and community institutions appear to have filled the gap normally held by government bodies such as the CDC or the local Department of Health—and provided trusted information to their constituents including public health information. As shown in Fig. 3, more participants reported that they completely trusted information provided by their local community institutions than from any other information source. Open-ended responses support this observation with comments consistently referring to the clarity of communications from local religious leaders and their institutions.

Individual Factors

On an individual level, religious and spiritual factors are recognized as salient social determinants of both physical (Oman 2018; Ransome 2020) and psychological health (Rosmarin and Koenig 2020). In particular, it is known that during times of crisis, religious and spiritual factors can play a crucial role in one’s ability to cope (Abu-Raiya and Pargament 2015; Pirutinsky et al. 2011; Rosmarin et al. 2009) and that aspects of religious involvement have the potential to mitigate or exacerbate psychological distress (Pargament et al. 2013; Ransome 2020). Taking the current pandemic as an example, the catastrophic tolls of COVID-19 have led to a renewed interest in the field of chaplaincy, with the importance of attending to individuals’ and their families’ spiritual needs a particular focus at this time (Barber 2020; Cadge 2020).

The nature of this sample precluded our ability to quantitatively assess the role of individual religious factors in distress and anxiety. As the vast majority of the sample identified as highly religious, variability was too limited to assess whether religious commitment moderated distress levels, nor did we formally measure aspects of religious experience such as the impact of their religion on coping. However, participants reported that the ability to participate in religious life remotely via communal prayer groups, study groups and life-cycle events was an important part of managing their quarantine. Future studies should examine how well-established factors relating to religion, spirituality and health, prayer, attachment to God and intrinsic religious orientation are related to managing the ongoing psychological and social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, spiritually centered clinical interventions may be appropriate when applied on an individual level (Rosmarin 2018) as people begin to grapple with the existential nature of the unfolding pandemic.

Stigma

The sample was highly religious with 82.5% reporting that religion was either very important to them or the center of their life. It is therefore not surprising that religious identity was at the forefront when reporting on experiences of stigma. Over half of the sample (50.3%) reported either anticipating stigma or actually experiencing stigma due to the association of their religious community with the pandemic. Further, the extent to which they felt stigmatized on either an individual or community level was associated with their reported levels of anxiety and distress. Open-ended responses suggested that while many individuals were concerned with general COVID-19-related stigma, most were concerned with potential negative repercussions for the Jewish community at large. Specifically, there was concern about the perception that Jews, and specifically Orthodox Jews, were to blame for spreading COVID-19 in New York. This perception was valid, considering that it appears similar to the high levels of anti-Chinese sentiment that began to percolate around New York City and other parts of the USA in the early stages of the pandemic (He et al. 2020). Indeed, a recent report (Schwartz 2020) recorded an increase in worldwide anti-Semitism since the start of the pandemic consistent with historically anti-Semitic tropes related to Jews and other minorities as being “unclean” and spreading infection. In fact, recent empirical research suggests that this perception about minority groups often persists despite evidence suggesting a greater emphasis on cleanliness among many religious individuals (Litman et al. 2019).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically reshaped our lives. As a society, we will need to find ways to continue to adapt to what will be a prolonged crisis. The fact that the first large-scale community quarantine in the USA was of a tight-knit religious community has offered a glimpse into what a communal religious response might look like as we continue to endure lockdowns, social distancing and periodic quarantines. The current sample was unique in multiple ways. Community members all resided in the greater New York area and were affiliated with large religious institutions with significant infrastructure and resources. Religious leaders and community members enacted a quick and coordinated response to a public health crisis by organizing community outreach, mobilizing tangible services, conducting virtual religious services and relaying health-related information.

Religious institutions are often at the center of individuals’ communal lives, and while formal religious services remain restricted or limited, organizations will need to demonstrate flexibility and resourcefulness in order to support their communities. Even when physically distancing, people within religious communities still turn to their communities and religious leaders for information and support.

In addition to the responsibility of religious leaders, it behooves public health officials to form public health partnerships with local religious institutions/leaders to promote wellness and prevent the spread of COVID-19. The instrumental role that religious leaders can play in public health efforts has been well documented (Taylor et al. 2019), and public health partnerships between religious leaders and health care have been used in a variety of health promotions programs to varying degrees of success (Darnell et al. 2006; Miller 2018; Welch and Hughes 2020). Religious organizations should be viewed as valuable community partners in disseminating and supporting public health messaging. This is perhaps most important in traditionally underserved communities and those with unequal access to health care. In addition, as misinformation regarding COVID-19 and myriad other health-related issues abound, religious leaders have an opportunity and responsibility to provide scientifically informed health education. Future research should examine the best ways to form partnerships between religious institutions and leaders and public health officials in order to create systems that can communicate clearly in fast-moving situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Religious institutions can play a vital role in supporting individuals’ psychological needs by providing social support, and promoting feelings of unity within the context of each institution’s religious and spiritual framework. This may be especially effective during the COVID-19 pandemic as the multitude of medical, social and economic issues created by this crisis call for a coordinated response from institutions ranging from government to health care to religious institutions. During this unprecedented time as we face a crisis that has the potential to undermine much of our societal infrastructure, religious institutions and their leaders will have an even greater role to play in managing the social and psychological as well as public health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding

There was no funding associated with this project.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

There authors declare no ethical conflicts or conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sarah L. Weinberger-Litman, Email: sweinberger@mmm.edu

Leib Litman, Email: leib.litman@touro.edu.

Zohn Rosen, Email: zr2153@cumc.columbia.edu.

David H. Rosmarin, Email: drosmarin@mclean.harvard.edu

Cheskie Rosenzweig, Email: cr2769@tc.columbia.edu.

References

- Abu-Raiya H, Pargament KI. Religious coping among diverse religions: Commonalities and divergences. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2015;7(1):24. doi: 10.1037/a0037652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anshel MH, Smith M. The role of religious leaders in promoting healthy habits in religious institutions. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;53(4):1046–1059. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber E. The plight of a hospital chaplain during the coronavirus epidemic. New York: The New Yorker; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):893. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadge W. The rise of the chaplains. New York: The Atlantic; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JS, Chang C-H, Calhoun EA. Knowledge about breast cancer and participation in a faith-based breast cancer program and other predictors of mammography screening among African American women and Latinas. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(3_suppl):201S–212S. doi: 10.1177/1524839906288693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazen JM, Kanapathipillai R, Campion EW, Rubin EJ, Hammer SM, Morrissey S, Baden LR. Ebola and quarantine. New York: Mass Medical Society; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner PJ, Moallef P. Psychological impact on SARS survivors: Critical review of the English language literature. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2015;56(1):123. doi: 10.1037/a0037973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(7):1206. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, He L, Zhou W, Nie X, He M. Discrimination and social exclusion in the outbreak of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(8):2933. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H, Yim HW, Song Y-J, Ki M, Min J-A, Cho J, Chae J-H. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiology and Health. 2016;38:e2016048. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2016048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA, Hood RW., Jr Intrinsic–extrinsic religious orientation: The boon or bane of contemporary psychology of religion? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1990;29:442–462. doi: 10.2307/1387311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Litman L, Robinson J, Weinberger-Litman SL, Finkelstein R. Both intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientation are positively associated with attitudes toward cleanliness: Exploring multiple routes from godliness to cleanliness. Journal of Religion and Health. 2019;58(1):41–52. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder H, Hossain MM, Das A. Geriatric care during public health emergencies: Lessons learned from novel corona virus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2020;63:1–2. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2020.1746723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DG. Considering weight loss programs and public health partnerships in American evangelical protestant churches. Journal of Religion and Health. 2018;57(3):901–914. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oman D. Why religion and spirituality matter for public health: Evidence, implications, and resources. Berlin: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Mahoney AE, Shafranske EP. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 2): An applied psychology of religion and spirituality. New York: American Psychological Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pirutinsky S, Rosmarin DH, Pargament KI, Midlarsky E. Does negative religious coping accompany, precede, or follow depression among Orthodox Jews? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;132(3):401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransome Y. Religion spirituality and health: New considerations for epidemiology. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2020 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Z., Weinberger-Litman, S. L., Rosenzweig, C., Rosmarin, D. H., Muennig, P., Carmody, E. R., et al. (2020). Anxiety and distress among the first community quarantined in the U.S due to COVID-19: Psychological implications for the unfolding crisis. 10.31234/osf.io/7eq8c. (Preprint).

- Rosmarin DH. Spirituality, religion, and cognitive-behavioral therapy: A guide for clinicians. New York: Guilford Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin DH, Koenig HG. Handbook of spirituality, religion, and mental health. Berlin: Academic Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin DH, Pargament KI, Krumrei EJ, Flannelly KJ. Religious coping among Jews: Development and initial validation of the JCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(7):670–683. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, F. (2020). Coronavirus sparks rise in anti-Semitic sentiment, Researchers say. Wall Street Journal.

- Tanner BA. Validity of global physical and emotional SUDS. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2012;37(1):31–34. doi: 10.1007/s10484-011-9174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B, Croff JM, Story CR, Hubach RD. Recovering from an epidemic of teen pregnancy: The role of rural faith leaders in building community resilience. Journal of Religion and Health. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00863-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch P, Hughes BL. Rural black pastors: The influence of attitudes on the development of HIV/AIDS programs. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2020;7(1):90–98. doi: 10.1007/s40615-019-00637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]