Abstract

The pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has become a global threat to public health. Functional impairments in multiple organs have been reported in COVID-19, including lungs, heart, kidney, liver, brain, and vascular system. Patients with metabolic-associated preconditions, such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes, are susceptible to experiencing severe symptoms. The recent emerging evidence of coagulation disorders in COVID-19 suggests that vasculopathy appears to be an independent risk factor promoting disease severity and mortality of affected patients. We recently found that the decreased levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterols (LDL-c) correlate with disease severity in COVID-19 patients, indicating pathological interactions between dyslipidemia and vasculopothy in patients with COVID-19. However, this clinical manifestation has been unintentionally underestimated by physicians and scientific communities. As metabolic-associated morbidities are generally accompanied with endothelial cell (EC) dysfunctions, these pre-existing conditions may make ECs more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 attack. In this mini-review, we summarize the metabolic and vascular manifestations of COVID-19 with an emphasis on the association between changes in LDL-c levels and the development of severe symptoms as well as the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying the synergistic effect of LDL-c and SARS-CoV-2 on EC injuries and vasculopathy.

Keywords: COVID-19, endothelial cells, hypertension, LDL, obesity, SARS-CoV-2, thrombosis, vasculopathy

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (15), which was first reported in December 2019 from Wuhan, China (18). As of May 25, 2020, more than 5.4 million infections and 345,000 deaths have been reported in 188 countries and regions. The United States alone has registered more than 1.6 million cases and 97,000 deaths (20a). Scientists are just beginning to understand the nature of the harm caused by this disease. Patients with metabolic-associated preconditions are susceptible to experience more severe symptoms. Dyslipidemia leads to dysfunction of blood vessels in various cellular activities and is intrinsically associated with these metabolic and vascular comorbidities. Recently, decreases in levels of total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) have been reported in COVID-19 patients (8, 50), indicating a potential pathophysiologic interaction between lipid metabolism and vasculopathy in disease progression. In this review, we will briefly discuss clinical characteristics, particularly dyslipidemia in COVID 19 and provide insights into the speculative underlying mechanisms.

SARS-CoV-2 AND CLINICAL FEATURES OF COVID-19

Similar to the SARS-CoV and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERSCoV-2), SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus and is the newest and seventh known coronavirus that is capable of infecting human beings. SARS-CoV-2 is the causative pathogen for COVID-19 (1). The RNA genome of SARS-CoV-2 has 29,891 nucleotides (GenBank, MN908947), sharing 79% sequence identity with SARS-CoV and 50% with Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (7a, 28). The phylogeny of this coronavirus shows that it is most close to the bat coronavirus (BatCoV) RaTG13, with 96·3% sequence identity (55). The SARS-CoV-2 is considered to be zoonotic (13, 18). However, the intermediate host(s) are yet to be determined. The SARS-COV2 Spike (S) protein, comprised of subunits S1 and S2, is thought to mediate the virus entering host cells via surface angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (28, 47). Host protease transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) promotes SARS-CoV-2 entry of target cells. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 have been found to coexpress in lung type II pneumocytes, ileal absorptive enterocytes, and nasal goblet secretory cells (56), which are thought to be host determinants for viral infection in the initial stage.

COVID-19 patients can be asymptomatic or symptomatic. The incubation period from exposure to onset of symptoms is ~5.1 days. Majority (97.5%) of patients develop symptoms within 11.5 days after infection (23). Pathologically, SARS-CoV-2 can cause damage to almost every vital organ in the body, including the lungs, heart, liver, kidney, eyes, blood vessels, intestines, and brain, with devastating consequences. The virus enters the nose and throat, multiplies within cells and marches down into the lungs, leading to pneumonia. Damage to the lungs can be long term for some recovered patients; this has been observed in surviving SARS patients (53). In serious cases, SARS-CoV-2 injures many other organs and results in deep and systemic damages. Mortality rate of COVID-19 varies in different geographic locations and patient populations, ~13.6% in Italy, and 5.7% in the United States. The time from the onset of symptoms to death ranges from 6 to 41 days (39, 48).

METABOLIC-ASSOCIATED COMORBIDITIES AND DYSLIPIDEMIA IN COVID-19

Patients with metabolic-associated preconditions are susceptible to the SARS-CoV-2 attack. A meta-analysis included six studies with 1,527 patients with COVID-19 in China revealed that the proportions of hypertension, cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disorders, and diabetes mellitus were 17.1%, 16.4%, and 9.7%, respectively (24). Wei et al. (49) showed that the main comorbidities in patients in Wuhan were hypertension (32%), diabetes mellitus (12%), and cardiovascular disorders (8%). Although the proportions of these comorbidities in patients in Europe and the United States have been found much higher. In 5,700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in New York City, the major comorbidities for patients with COVID-19 are hypertension (56.6%), obesity (41.7%), diabetes mellitus (33.8%), and coronary heart diseases (11.1%) (34). A study including 388 patients in Italy reported the comorbidities are hypertension (47.2%), diabetes mellitus (22.7%), and coronary heart diseases (13.9%) (27), suggesting that metabolic and vascular disorders could have contributive roles in the rapid progression and poor prognosis of affected patients (31). As the studies only analyze the hospitalized patients, the comorbid conditions of asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic patients are unknown, so the overall prevalence of comorbidities in COVID-19 has been not fully established.

More importantly, patients with these preconditions are likely to experience more pronounced symptoms. Guan et al. (15) included 1,099 patients with COVID-19 reported that, compared with severe and nonsevere groups, the proportions of hypertension were 23.7% versus 13.4%, diabetes mellitus 16.2% versus 5.7%, and cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disorders 8.1% versus 1.8%. Another study reported that in 54 nonsurviving patients out of a cohort of 191 patients, the ratios of hypertension, cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus were 48%, 24%, and 31%, respectively, much higher than survivors in the same cohort (54). Notably, the overall fatality of patients with no comorbidities is ~0.9%; but the mortality rates for patients with comorbidities are much higher: 10.5% for those with cardiovascular disorders, 7.3% for diabetes, 6% for hypertension (7b), which may be a result of the hyperinflammatory response in a combination with pre-existing endothelial dysfunctions. Patients showed elevations of a series of cancer biomarkers, reflecting acute and diffuse injuries in lungs and probably other tissues as well (49).

One pathogenic cofactor associated with hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders is hypercholesterolemia. The reports about dyslipidemia in patients with SARS are few. One report showed a lower level of TC in patients with SARS compared with healthy subjects (41). Another study reported aberrant lipid metabolism in recovered SARS patients 12 yr after infection (52). These studies suggest that dyslipidemia can occur in patients with coronavirus-related diseases, but the topic has not generated much attention among physicians and researchers. We recently reported dyslipidemia in patients with COVID-19 and demonstrated that the degree of decreased LDL-c was associated with severity and mortality of the disease (8, 50). In a small cohort of 21 patients, lipid profiles were checked before viral infections and during the course of their illness. The levels of LDL-c, TC, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) in patients decreased when they were hospitalized and remained low during the treatment. The LDL-c and TC levels recovered to baseline in discharged patients but in those that did not survive, levels decreased continuously (8). In another study of a large cohort of patients (n = 597), lipid data at the time of admission were extracted from the charts of patients with mild, severe, and critical symptoms. LDL-c and TC levels were decreased in patients with COVID-19 compared with the levels from healthy subjects and the degree of reduction correlated with the progression of symptoms (50). HDL-c only decreased in critically ill patients when compared mild and severe cases (50). Thus, LDL-c seems a major player accounting for the dyslipidemia in COVID-19. It was less likely that dyslipidemia in patients with COVID-19 was a side effect caused by interventions, because the patients 1) had decreased LDL-c levels before interventions, 2) received varieties of medications during the disease progression, and 3) had their levels of LDL-c recovered under the same remedies when their symptoms were mitigated (8). Furthermore, a recent proteomic and metabolomic study from the sera of patients with COVID-19 showed a massive suppression of metabolism, including dysregulated levels of multiple apolipoproteins (Apo) such as Apo A1, Apo A2, Apo H, Apo L1, Apo D, and Apo M (14).

Decreased LDL-c, HDL-c, and TC have been reported in many chronic diseases or terminal illness, such as lung cancers (44). Chronic inflammation caused by viral infections may result in dyslipidemia in patients as well. For example, patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) show a decrease in HDL-c and increase in LDL-c levels (3, 35); low levels of LDL-c and HDL-c were shown in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection in the cirrhosis phase (5). In a meta-analysis of nine studies including 1,953 patients, Lima et al. (26) found serum TC and LDL-c levels decreased in patients infected with dengue virus. Moreover, in a 15-yr follow-up multi-ethnic cohort of more than 120,000 adults, Iribarren et al. (20) reported TC was inversely and strongly correlated (or associated) with infections requiring in-hospital treatment or being acquired in the hospital, with the exception of respiratory illness and HIV. Taken together, these reports suggest that chronic inflammation may be involved in the pathological metabolic processing of lipids and ultimately result in the observed dyslipidemia in such patients.

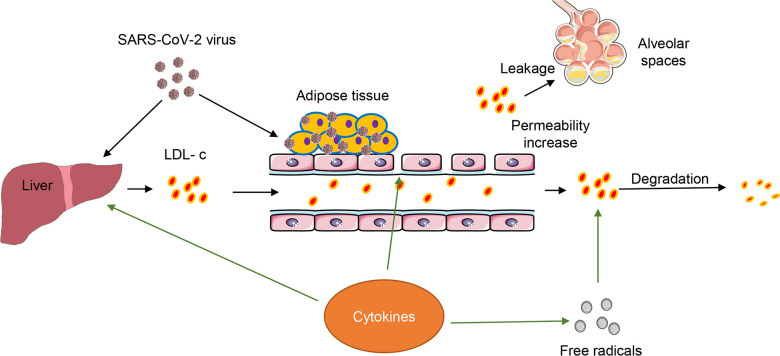

Dyslipidemia in COVID-19 is considered to result from complicated biological and pathological processes triggered by SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1). As an acute infectious and inflammatory disease, COVID-19 presents several pathological characteristics that could account for dyslipidemia. Damage of liver function caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection could interfere with LDL uptake and reduce LDL biosynthesis; however, serum liver function tests, including alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), usually show a moderate increase in less than 50% of patients (8, 49, 50). While this suggests a generally minor effect on patients’ liver function, the levels of these enzymes may not accurately reflect the liver’s ability in regard to LDL synthesis and uptake. Sterol regulatory-element binding proteins (SREBPs) are master transcriptional factors that regulate the expression of a wide range of enzymes required for lipid synthesis. Intracellular lipid homeostasis is regulated by many endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane integral sensors such as SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP), squalene monooxygenase (SM), and nuclear factor erythroid 2 related factor-1 (Nrf1), etc. (6, 37, 45). Upon cholesterol deprivation, SCAP will bind to SREBPs in ER, escort them to the Golgi, and facilitate proteolysis of SREBPs, thus resulting in release of SREBP transcription factor domains and entry of nucleus to promote cholesterol synthesis and uptake (45). It is reasonable to speculate that the cholesterol synthesis and uptake pathways have been altered in patients with COVID-19, since recent emerging evidence has shown that SARS-CoV-2 infection can suppress the levels of many proteins related to cholesterol metabolism (4, 14). A thorough investigation will be required in the future to dissect the potential mechanism regarding whether and how SARS-CoV-2 modulates the expressions of these cholesterol sensing proteins in host cells. Second, SARS-CoV-2-induced hyperinflammation in hosts alters lipid metabolism. Inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, have been shown to modify lipid composition, function, and transportation in patients with HIV (9). The COVID-19-associated cytokine storm is thought to be a causative factor leading to fatality in patients with COVID-19. IL-6 was increased in 96% of all patients in our studies (8, 49), suggesting that cytokines may contributes to the abnormality of LDL in our patients. Third, increased vascular permeability caused SARS-CoV-2 infection may lead to a leakage of LDL into alveolar spaces to form exudate, a substance containing high levels of proteins and cholesterols (16, 25). Exudates have been found in lung autopsies from patients with SARS, in cynomolgus macaques infected with SARS-CoV (19, 22, 32), as well as COVID-19 lung pathology (43). Fourth, free radicals signaling, which is generally elevated in host cells with a viral infection (8), accelerates the degradation of lipids in COVID-19. Furthermore, cholesterol provides a platform facilitating the interaction of SARS S protein with ACE2 for entry of targeted cells (12). Adipose/fat tissue may serve as a reservoir for SARS-CoV-2 in patients (36). Finally, a recent study showed that proteins related to cholesterol metabolism decrease in SARS-CoV-2-infected human colon epithelial carcinoma cells, including Apo E, Apo B, LDL receptor related protein (LRP), etc. (4). Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 likely imposes a direct impact on lipid metabolism including the endocytosis of LDL-c via LRP. However, whether the level of LDL receptor (LDLr) is altered in patients or not remains unknown, which will need further investigations.

Fig. 1.

Hypothetical interactions among severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), and inflammatory cytokines in patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Outline showing the proposed pathological processes of dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 and the entangled roles of LDL-c and hyperinflammation. Both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2-induced inflammatory cytokines regulate the biosynthesis and metabolism of LDL-c. Simultaneously, adipose tissues can be a potential reservoir for SARS-CoV-2. Inflammation- induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling can facilitate the degradation of LDL-c. The increased vascular permeability by hyperinflammation can promote the LDL-c leakage into alveolar spaces.

DYSLIPIDEMIA AND COAGULOPATHY IN COVID-19

Patients with COVID-19 have shown elevated coagulative and cardiac biomarkers such as D-dimer, fibrinogen, high-sensitivity troponin I, and creatinine kinase–myocardial band (10, 40). Emerging evidence has shown that venous and arterial coagulopathies have been reported with an incident rate ranging from 8 to 15% in numerous studies, even in an early stage of the disease (17, 21, 27). Thrombotic events can occur in deep veins as well as in lungs, heart and brain, causing pulmonary embolisms, stroke and myocardial infarction (45). The majority of patients with COVID-19 who did not survive had some evidence of coagulopathy (42). All data demonstrate that coagulation activation and endothelial dysfunction are prominent and independent factors underlying the COVID-19 severity and fatality in patients (17), which should be given urgent attention.

A high level of LDL-c is considered a risk factor associated with microvascular dysfunctions in hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders (7); such comorbidities exist in more than half of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Europe and the United States (27). It is reasonable to postulate that LDL-c contributes to vasculopathy in patients with COVID-19. Endothelial cell (EC) injuries triggering thrombotic events may result either directly from viral infection or indirectly from an effect on ECs lining atherosclerotic areas. For the first scenario, SARS-CoV-2-induced acute endothelial injury could be a factor. Cholesterol has been reported to be necessary for SARS virus replication in early stage in host cells (29). Therefore, it is possible that cholesterol participates in the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in host cells, including ECs. The high virulence of SARS-CoV-2 to the infected ECs could cause acute and local blood vessel injuries, thus triggering coagulopathies as significant clinical sequelae. For the second scenario, accumulation of LDL in the subendothelium, where oxidative modifications on LDL occur, becomes an early step in atherogenesis (30, 51). Vulnerable plaques with enrichment of inflammatory cells and lipids will release highly thrombogenic contents and trigger an atherothrombotic occlusion upon being ruptured (11, 38). One speculation is that the ECs within atherosclerotic plaques are more vulnerable to an attack from SARS-CoV-2 or inflammatory storms, causing a rupture of plaques, and a high risk of developing coagulopathy in patients with cardiovascular associated preconditions.

Remedies for active management of LDL-c levels such as statins may be beneficial to those patients with COVID-19 who have preconditions of hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders. Hyperlipidemia is a significant contributor to endothelial dysfunction leading to atherosclerosis. Lowering LDL-c levels will reduce the degree of vasculopathy and thus protect the endothelial integrity from SARS-CoV-2 attack. Furthermore, it will be reasonable to postulate that SARS-CoV-2 can utilize cholesterol for multiplication, a mechanism that SARS-CoV has shown in the host cells (29). Therefore, decreases in cholesterol may be helpful to mitigate SARS-CoV-2 replications and viral load in patients.

Collectively, dyslipidemia in COVID-19 may be a result of complex metabolic and pathophysiologic processes. Given the dysregulated levels of LDL-c, malfunctioning ECs, thrombotic event, and the high incidence of metabolic-associated preconditions in patients with COVID-19, the contributive roles of LDL-c should not be underestimated. Future studies should investigate the correlation between high plasma LDL-c levels and the incidence of development of severe symptoms and the mechanisms by which LDL-c can facilitate and accelerate vasculopathy synergistic with SARS-CoV-2.

GRANTS

Funding this work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (Grant AR073172 to W.T.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.C. and R.Y. prepared figures; X.C. and W.T. drafted manuscript; X.C., R.Y., H.A., D.F., and W.T. edited and revised manuscript; X.C., R.Y., H.A., D.F., and W.T. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med 26: 450–452, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker J, Ayenew W, Quick H, Hullsiek KH, Tracy R, Henry K, Duprez D, Neaton JD. High-density lipoprotein particles and markers of inflammation and thrombotic activity in patients with untreated HIV infection. J Infect Dis 201: 285–292, 2010. doi: 10.1086/649560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bojkova D, Klann K, Koch B, Widera M, Krause D, Ciesek S, Cinatl J, Münch C. Proteomics of SARS-CoV-2-infected host cells reveals therapy targets. Nature. In press. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2332-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao WJ, Wang TT, Gao YF, Wang YQ, Bao T, Zou GZ. Serum lipid metabolic derangement is associated with disease progression during chronic HBV infection. Clin Lab 65: 190525, 2019. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2019.190525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chua NK, Howe V, Jatana N, Thukral L, Brown AJ. A conserved degron containing an amphipathic helix regulates the cholesterol-mediated turnover of human squalene monooxygenase, a rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis. J Biol Chem 292: 19959–19973, 2017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.794230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cromwell WC, Otvos JD. Low-density lipoprotein particle number and risk for cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep 6: 381–387, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s11883-004-0050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol 5: 536–544, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b.Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 41: 145–151, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan J, Wang H, Ye G, Cao X, Xu X, Tan W, Zhang Y. Letter to the Editor: Low-density lipoprotein is a potential predictor of poor prognosis in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Metabolism 107: 154243, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funderburg NT, Mehta NN. Lipid abnormalities and inflammation in HIV inflection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 13: 218–225, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s11904-016-0321-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao Y, Li T, Han M, Li X, Wu D, Xu Y, Zhu Y, Liu Y, Wang X, Wang L. Diagnostic utility of clinical laboratory data determinations for patients with the severe COVID-19. J Med Virol 92: 791–796, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gimbrone MA Jr, García-Cardeña G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ Res 118: 620–636, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glende J, Schwegmann-Wessels C, Al-Falah M, Pfefferle S, Qu X, Deng H, Drosten C, Naim HY, Herrler G. Importance of cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains in the interaction of the S protein of SARS-coronavirus with the cellular receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Virology 381: 215–221, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A, Satlin MJ, Campion TR Jr, Nahid M, Ringel JB, Hoffman KL, Alshak MN, Li HA, Wehmeyer GT, Rajan M, Reshetnyak E, Hupert N, Horn EM, Martinez FJ, Gulick RM, Safford MM. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med 382: 2372–2374, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Ramirez SI, Mateus J, Dan JM, Moderbacher CR, Rawlings SA, Sutherland A, Premkumar L, Jadi RS, Marrama D, de Silva AM, Frazier A, Carlin AF, Greenbaum JA, Peters B, Krammer F, Smith DM, Crotty S, Sette A. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. In press. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19 . Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382: 1708–1720, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heffner JE, Sahn SA, Brown LK. Multilevel likelihood ratios for identifying exudative pleural effusions(*). Chest 121: 1916–1920, 2002. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.6.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Fagot Gandet F, Fafi-Kremer S, Castelain V, Schneider F, Grunebaum L, Anglés-Cano E, Sattler L, Mertes PM, Meziani F; CRICS TRIGGERSEP Group (Clinical Research in Intensive Care and Sepsis Trial Group for Global Evaluation and Research in Sepsis) . High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med 46: 1089–1098, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395: 497–506, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang DM, Chamberlain DW, Poutanen SM, Low DE, Asa SL, Butany J. Pulmonary pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto. Mod Pathol 18: 1–10, 2005. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iribarren C, Jacobs DR Jr, Sidney S, Claxton AJ, Feingold KR. Cohort study of serum total cholesterol and in-hospital incidence of infectious diseases. Epidemiol Infect 121: 335–347, 1998. doi: 10.1017/S0950268898001435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Auwaerter PG. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. https://systems.jhu.edu/research/public-health/ncov/ [May 20, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, Kaptein FHJ, van Paassen J, Stals MAM, Huisman MV, Endeman H. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 191: 145–147, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuiken T, Fouchier RA, Schutten M, Rimmelzwaan GF, van Amerongen G, van Riel D, Laman JD, de Jong T, van Doornum G, Lim W, Ling AE, Chan PK, Tam JS, Zambon MC, Gopal R, Drosten C, van der Werf S, Escriou N, Manuguerra JC, Stöhr K, Peiris JS, Osterhaus AD. Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 362: 263–270, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13967-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, Jones FK, Zheng Q, Meredith HR, Azman AS, Reich NG, Lessler J. The incubation period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med 172: 577–582, 2020. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, Zhi L, Wang X, Liu L, Bi Z, Zhao Y. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol 109: 531–538, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, Ball WC Jr. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med 77: 507–513, 1972. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lima WG, Souza NA, Fernandes SOA, Cardoso VN, Godói IP. Serum lipid profile as a predictor of dengue severity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol 29: e2056, 2019. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, Cecconi M, Ferrazzi P, Sebastian T, Kucher N, Studt JD, Sacco C, Alexia B, Sandri MT, Barco S; Humanitas COVID-19 Task Force . Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res 191: 9–14, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, Bi Y, Ma X, Zhan F, Wang L, Hu T, Zhou H, Hu Z, Zhou W, Zhao L, Chen J, Meng Y, Wang J, Lin Y, Yuan J, Xie Z, Ma J, Liu WJ, Wang D, Xu W, Holmes EC, Gao GF, Wu G, Chen W, Shi W, Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 395: 565–574, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Liu DX, Tam JP. Lipid rafts are involved in SARS-CoV entry into Vero E6 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 369: 344–349, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maiolino G, Rossitto G, Caielli P, Bisogni V, Rossi GP, Calò LA. The role of oxidized low-density lipoproteins in atherosclerosis: the myths and the facts. Mediators Inflamm 2013: 714653, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/714653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oren O, Kopecky SL, Gluckman TJ, Gersh BJ, Blumenthal RS. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology, Clinical Spectrum and Implications for the Cardiovascular Clinician. American College of Cardiology; https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/04/06/11/08/covid-19-epidemiology-clinical-spectrum-and-implications-for-the-cv-clinician [April 06, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pei F, Zheng J, Gao ZF, Zhong YF, Fang WG, Gong EC, Zou WZ, Wang SL, Gao DX, Xie ZG, Lu M, Shi XY, Liu CR, Yang JP, Wang YP, Han ZH, Shi XH, Dao WB, Gu J. [Lung pathology and pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome: a report of six full autopsies]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 34: 656–660, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, Barnaby DP, Becker LB, Chelico JD, Cohen SL, Cookingham J, Coppa K, Diefenbach MA, Dominello AJ, Duer-Hefele J, Falzon L, Gitlin J, Hajizadeh N, Harvin TG, Hirschwerk DA, Kim EJ, Kozel ZM, Marrast LM, Mogavero JN, Osorio GA, Qiu M, Zanos TP; the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium . Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA 323: 2052, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose H, Hoy J, Woolley I, Tchoua U, Bukrinsky M, Dart A, Sviridov D. HIV infection and high density lipoprotein metabolism. Atherosclerosis 199: 79–86, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan PM, Caplice NM. Is adipose tissue a reservoir for viral spread, immune activation and cytokine amplification in COVID-19? Obesity. In press. doi: 10.1002/oby.22843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sacks D, Baxter B, Campbell BCV, Carpenter JS, Cognard C, Dippel D, Eesa M, Fischer U, Hausegger K, Hirsch JA, Shazam Hussain M, Jansen O, Jayaraman MV, Khalessi AA, Kluck BW, Lavine S, Meyers PM, Ramee S, Rüfenacht DA, Schirmer CM, Vorwerk D; From the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS), American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR), Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe (CIRSE), Canadian Interventional Radiology Association (CIRA), Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS), European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT), European Society of Neuroradiology (ESNR), European Stroke Organization (ESO), Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS), and World Stroke Organization (WSO) . Multisociety consensus quality improvement revised consensus statement for endovascular therapy of acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke 13: 612–632, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz SM, Galis ZS, Rosenfeld ME, Falk E. Plaque rupture in humans and mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 705–713, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000261709.34878.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, Fan Y, Zheng C. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 20: 425–434, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F, Gong W, Liu X, Liang J, Zhao Q, Huang H, Yang B, and Huang C. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. In press. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song SZ, Liu HY, Shen H, Yuan B, Dong ZN, Jia XW, Tian YP. [Comparison of serum biochemical features between SARS and other viral pneumonias]. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 16: 664–666, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 18: 844–847, 2020. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, Liu H, Xu H, Xiao SY. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 15: 700–704, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Umeki S. Decreases in serum cholesterol levels in advanced lung cancer. Respiration 60: 178–181, 1993. doi: 10.1159/000196195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vera-Sigüenza E, Catalán MA, Peña-Münzenmayer G, Melvin JE, Sneyd J. A mathematical model supports a key role for Ae4 (Slc4a9) in salivary gland secretion. Bull Math Biol 80: 255–282, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11538-017-0370-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol 94: e00127-20, 2020. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang W, Tang J, Wei F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol 92: 441–447, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei X, Su J, Yang K, Wei J, Wan H, Cao X, Tan W, Wang H. Elevations of serum cancer biomarkers correlate with severity of COVID-19. J Med Virol. In press. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei X, Zeng W, Su J, Wan H, Yu X, Cao X, Tan W, Wang H. Hypolipidemia is associated with the severity of COVID-19. J Clin Lipidol 14: 297–304, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams KJ, Tabas I. The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15: 551–561, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.15.5.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu Q, Zhou L, Sun X, Yan Z, Hu C, Wu J, Xu L, Li X, Liu H, Yin P, Li K, Zhao J, Li Y, Wang X, Li Y, Zhang Q, Xu G, Chen H. Altered lipid metabolism in recovered SARS patients twelve years after infection. Sci Rep 7: 9110, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09536-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang P, Li J, Liu H, Han N, Ju J, Kou Y, Chen L, Jiang M, Pan F, Zheng Y, Gao Z, Jiang B. Long-term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital-acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: a 15-year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Res 8: 8, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41413-020-0084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395: 1054–1062, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579: 270–273, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ziegler CGK, Allon SJ, Nyquist SK, Mbano IM, Miao VN, Tzouanas CN, Cao Y, Yousif AS, Bals J, Hauser BM, Feldman J, Muus C, Wadsworth MH II, Kazer SW, Hughes TK, Doran B, Gatter GJ, Vukovic M, Taliaferro F, Mead BE, Guo Z, Wang JP, Gras D, Plaisant M, Ansari M, Angelidis I, Adler H, Sucre JMS, Taylor CJ, Lin B, Waghray A, Mitsialis V, Dwyer DF, Buchheit KM, Boyce JA, Barrett NA, Laidlaw TM, Carroll SL, Colonna L, Tkachev V, Peterson CW, Yu A, Zheng HB, Gideon HP, Winchell CG, Lin PL, Bingle CD, Snapper SB, Kropski JA, Theis FJ, Schiller HB, Zaragosi LE, Barbry P, Leslie A, Kiem HP, Flynn JL, Fortune SM, Berger B, Finberg RW, Kean LS, Garber M, Schmidt AG, Lingwood D, Shalek AK, Ordovas-Montanes J, Banovich N, Barbry P, Brazma A, Desai T, Duong TE, Eickelberg O, Falk C, Farzan M, Glass I, Haniffa M, Horvath P, Hung D, Kaminski N, Krasnow M, Kropski JA, Kuhnemund M, Lafyatis R, Lee H, Leroy S, Linnarson S, Lundeberg J, Meyer K, Misharin A, Nawijn M, Nikolic MZ, Ordovas-Montanes J, Pe’er D, Powell J, Quake S, Rajagopal J, Tata PR, Rawlins EL, Regev A, Reyfman PA, Rojas M, Rosen O, Saeb-Parsy K, Samakovlis C, Schiller H, Schultze JL, Seibold MA, Shalek AK, Shepherd D, Spence J, Spira A, Sun X, Teichmann S, Theis F, Tsankov A, van den Berge M, von Papen M, Whitsett J, Xavier R, Xu Y, Zaragosi L-E, Zhang K; HCA Lung Biological Network. Electronic address: lung-network@humancellatlas.org; HCA Lung Biological Network . SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell 181: 1016–1035.e19, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]