Abstract

Background and Purpose

Identifying safe and effective compounds that target to mitophagy to eliminate impaired mitochondria may be an attractive therapeutic strategy for non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Here, we investigated the effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G) on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and the underlying mechanism.

Experimental Approach

Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease was induced by a high‐fat diet for 16 weeks. C3G was administered during the last 4 weeks. In vivo, recombinant adenoviruses and AAV8 were used for overexpression and knockdown of PTEN‐induced kinase 1 (PINK1), respectively. AML‐12 and HepG2 cells were used for the mechanism study.

Key Results

C3G administration suppressed hepatic oxidative stress, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation and steatosis and improved systemic glucose metabolism in mice with NAFLD. These effects of C3G were also observed in palmitic acid‐treated AML‐12 cells and hepatocytes from NAFLD patients. Mechanistic investigations revealed that C3G increased PINK1/Parkin expression and mitochondrial localization and promoted PINK1‐mediated mitophagy to clear damaged mitochondria. Knockdown of hepatic PINK1 abolished the mitophagy‐inducing effect of C3G, which blunted the beneficial effects of C3G on oxidative stress, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, hepatic steatosis and glucose metabolism.

Conclusion and Implications

These results demonstrate that PINK1‐mediated mitophagy plays an essential role in the ability of C3G to alleviate NAFLD and suggest that C3G may be a potential drug candidate for NAFLD treatment.

Abbreviations

- BECN1

beclin 1

- BW

body weight

- C3G

cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside

- CQ

chloroquine

- HFD

high fat diet

- LW

liver weight

- NAFLD

non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NLRP3

NLR family pyrin domain containing 3

- NRF‐1

nuclear respiratory factor 1

- NRF‐2

nuclear factor erythroid derived 2 like 2

- PGC‐1α

peroxisome proliferative activated receptor, γ, coactivator 1α

- PIK3C3

PI3K catalytic subunit type 3

- PINK1

PTEN‐induced kinase 1

- TFAM

mitochondrial transcription factor A

- TFEB

transcription factor EB

What is already known

Damaged mitochondria release excessive ROS, which activate inflammation and exacerbate hepatic steatosis.

Mitophagy, mitochondria‐specific autophagy, is an efficient way to clear damaged mitochondria.

What this study adds

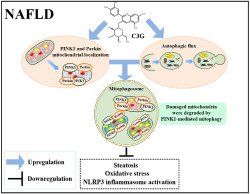

Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G) elevated PINK1 and Parkin protein expression and mitochondrial localization.

C3G attenuated hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation by inducing PINK1‐mediated mitophagy.

What is the clinical significance

C3G may be a useful therapeutic agent for the treatment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

Mitophagy may hold promise as a therapeutic target in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease.

1. INTRODUCTION

Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a major cause of liver disease worldwide and is defined as the accumulation of fat in the liver in individuals who do not consume excessive alcohol. The global prevalence of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease is 25.24% and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease may progress to non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis and cirrhosis or progress directly to hepatocellular carcinoma (Younossi et al., 2016). However, no pharmacological treatment approved by the US Food and Drug Administration is currently available. Accordingly, there is an urgent need to obtain a better understanding of the pathogenesis of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and discover effective therapeutic agents that can alleviate it.

Mitochondria orchestrate hepatic energy metabolism homeostasis by substrate oxidation, tricarboxylic acid cycle, adenosine triphosphate synthesis and ROS formation (Koliaki et al., 2015). Its dysfunction is associated with the progression of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and several studies have reported that dysfunctional mitochondria accumulated in the livers of patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Begriche, Massart, Robin, Bonnet, & Fromenty, 2013; Wang et al., 2015). Impaired mitochondria lead to the overproduction of ROS, which induce hepatic oxidative stress and aggravate lipid accumulation. Besides, excessive ROS activate the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which induces the cleavage and activation of Caspase 1 and further matures the proinflammatory cytokines IL‐1β and IL‐18 (Zhou, Yazdi, Menu, & Tschopp, 2011). Over‐activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome exacerbates hepatic steatosis (Angulo et al., 2015; Wan et al., 2016). Consequently, the clearance of damaged mitochondria may be an important implication for potential therapeutic applications of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Mitophagy, a mitochondrion‐specific form of autophagy, is the fundamental process of clearing damaged mitochondria to the maintenance of cellular homeostasis (Klionsky et al., 2016). Hence, defective mitophagy leads to accumulation of damaged mitochondria, mitochondrial fragmentation and oxidative stress (Bingol & Sheng, 2016; Bueno et al., 2015; Lazarou et al., 2015), which are highly reminiscent of metabolic defects in patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Although the blocked autophagic flux is observed in the livers of patients or mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Gonzalez et al., 2014; Tanaka et al., 2016), the hepatic mitophagy status and precise molecular mechanisms are largely unknown in patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Increasing evidence demonstrated that mitophagy was highly regulated by the PTEN‐induced kinase 1 (PINK1)–Parkin pathway (Klionsky et al., 2016) and loss of PINK1 led to defective mitophagy (Bueno et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2011). Accordingly, impaired PINK1‐mediated mitophagy may be associated with the excessive production of ROS and subsequently activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in the liver of patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nevertheless, the exact roles of PINK1‐mediated mitophagy in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease have not been elucidated. Therefore, investigation of the mechanism underlying the role of PINK1‐mediated mitophagy on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease is crucial for exploiting mitophagy as a therapeutic target in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Dietary strategies for alleviating non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease have been adopted in recent years as an alternative to pharmaceutical interventions. Several studies reported that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G, Figure S1), one of the most abundant forms of anthocyanins which belong to flavonoid family (Galvano et al., 2004), improved oxidative stress and hepatic steatosis in mice (Guo et al., 2012; Zhu, Jia, Wang, Zhang, & Xia, 2012). The extracts of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside rich‐black soybean testa could reduce visceral fat and improve plasma lipid profiles in obese adults and rats (Jeon, Han, Lee, Hong, & Yim, 2012; Kwon et al., 2007). These observations underscore the need to evaluate the rational utility of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease treatment and to investigate the mechanisms involved. Herein, we found that PINK1‐mediated mitophagy was impaired in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice and patients. Moreover, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside, a multi‐target drug, promoted PINK1‐mediated mitophagy and autophagic flux to alleviate hepatic oxidative stress, NLRP3 inflammasome activation and steatosis. Our results imply cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside as a potential therapeutic agent against non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and highlight that mitophagy may hold promise as a therapeutic target in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease.

2. METHODS

2.1. Reagents

An antibody specific for PINK1 (1:200; sc‐517353) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). An antibody specific for NLRP3 (1:1,000; 15101; RRID:AB_2722591) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies specific for p62 (1:2,000; ab101266; RRID:AB_10675814), LC3 (1,000; ab48394; RRID:AB_881433), Pro‐Caspase‐1 (1:5,000; ab201476), IL‐1β (1:1,000; ab9722), Parkin (1:2,000; ab179812), COX IV (1:1,000; ab14744) and TOM20 (1:2,000; ab186735) and secondary anti‐mouse and anti‐rabbit IgG (1:5,000; ab205719 and ab205718, respectively) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). FITC‐conjugated goat anti‐mouse IgG (1:200; 115‐095‐003) and anti‐rabbit IgG (1:200; 111‐095‐003) and Cyanine Cy™3‐conjugated goat anti‐rabbit IgG (1:500; 111‐165‐003) and anti‐mouse IgG (1:200; 115‐165‐003) were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (greater than 97%, HPLC) was purchased from Polyphenols Laboratories (Sandnes, Norway) and dissolved in DMSO (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for in vitro experiments. The final concentration of DMSO for all experiments and treatments was maintained at less than 0.1%. Palmitic acid (P0500; Sigma‐Aldrich) was dissolved in 0.1‐M NaOH at 70°C and then complexed with 10% BSA at 55°C for 10 min to achieve the final palmitate concentration (100 mM). Chloroquine (CQ, PHR1258) was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. PINK1 siRNA (sc‐44599 and sc‐44598) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

2.2. Human liver specimens and primary human hepatocyte isolation

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and approved by the ethics committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University (2016‐417). Informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in this study. Histopathologic diagnoses of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease were made in accordance with characteristic histological features (Brunt, Kleiner, Wilson, Belt, & Neuschwander‐Tetri, 2011). Samples with necroinflammation and fibrosis were excluded. The study comprised 15 obese patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. These patients were selected for treatment with bariatric surgery. We further studied 15 healthy lean volunteers who were undergoing select abdominal surgeries, such as herniotomy or cholecystectomy. All surgical liver biopsies were collected during surgery. None of the patients tested positive for infection with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus. Patients with other causes of chronic liver disease or patients receiving potentially hepatotoxic drugs were excluded. In addition, the included patients consumed less than 20 g of alcohol day‐1. After a 12‐h overnight fast, clinical and anthropometric data and venous blood samples were obtained from each patient. A basic description of the patients is presented in Table S1.

Primary human hepatocytes were isolated using a previously described two‐step collagenase method (LeCluyse et al., 2005). Cellular viability was assessed by the trypan blue dye exclusion test. Hepatocytes were seeded into a six‐well tissue culture plate (2 ml per well) at 1 × 106 cells·ml−1 and the medium was changed 3 h later to remove unattached hepatocytes.

2.3. Animals and treatment

The Ethics Committee on the Use and Care of Animals at Jilin University approved the study protocol (Changchun, China). The animals received humane care according to the criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health. Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath & Lilley, 2015) and with the recommendations made by the British Journal of Pharmacology. Experimental protocols and design adheres to BJP guidelines (Curtis et al., 2015). Male 8‐ to 10‐week‐old mice were purchased from the Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). All mice were kept in a standard environment with a 12‐h dark/light cycle (lights on at 06:30 h). The temperature and humidity were maintained at 23 ± 3°C and 35 ± 5%, respectively. The mice were fed a chow diet (D12450B, 10% kcal from fat, Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), a high fat diet (HFD, D12492, 60% kcal from fat, Research Diet), or an high fat diet containing 0.2% cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (2 g of powder cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside was weighed and mixed well with 1‐kg high fat diet). The detailed groups and the number of mice included are shown in the figure legends.

2.4. Energy expenditure measurement

The energy expenditure was monitored using an OxyMas Comprehensive Laborary Animal Monitoring System (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA). Mice were acclimated to the system for 24 h and then the oxygen consumption rate (VO2), carbon dioxide production rate (VCO2) and physical activity of each mouse were measured in the following 24 h. The energy expenditure was automatically calculated by the system based on VO2, VCO2 and body weight.

2.5. Cell culture and treatment

AML‐12 cells, an immortalized normal mouse hepatocyte cell line, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA, CRL‐2254). The cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 (SH30023.01, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (10099141, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1% insulin–transferrin–selenium (I3164, Sigma‐Aldrich) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C under 5% CO2. HepG2 human hepatocarcinoma cells (ATCC, HB‐8065; RRID:CVCL_0027) were maintained in DMEM (SH30021.01, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (10099141, Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C under 5% CO2. Mycoplasma contamination was negative for all cells.

To mimic in vivo hepatic steatosis, hepatocytes were maintained in medium containing 2% BSA and treated with 400‐μM palmitic acid for 12 h. To study the effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on autophagy, lipid metabolism, NLRP3 inflammasome and oxidative stress, the cells were treated with 100‐μM cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside for 12 h with or without palmitic acid treatment. To block autophagy, hepatocytes were treated with 50‐μM chloroquine for 4 h. To knockdown PINK1 in vitro, PINK1‐siRNA was transfected into hepatocytes using Lipofectamine 2000 (11668019, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To overexpression of GFP‐LC3, the cells were transfected with the recombinant adenovirus GFP‐LC3 (Vigene Biosciences, Jinan, Shandong, China). To study the colocalization of PINK1/LC3/GFP‐LC3 with mitochondria, the cells were treated with palmitic acid and then treated with or without 100‐μM cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside for 6 h, or the cells were transfected with PINK1‐siRNA and treated with palmitic acid and then treated with 100‐μM cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside for 6 h. The cell treatments and detailed group information are shown in the figure legends.

2.6. Transmission electron microscopy

The ultrastructural characteristics of autophagosomes were visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Du, Shen, et al., 2018). Liver biopsies and hepatocytes were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 12 h and then post‐fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h. Subsequently, the samples were dehydrated in an ethanol series and infiltrated with Spurr's resin. Ultrathin sections (50 nm) were cut and stained with 4% uranyl acetate and 0.2% lead citrate. Observations were performed on an H‐7650 electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan). Autophagosomes were quantified as previously described (Backues, Chen, Ruan, Xie, & Klionsky, 2014). Autophagosomes were counted from at least 20 random cells in each sample and expressed as the number of autophagosomes per cell.

2.7. Immunofluorescence assay

Immunofluorescence assays were performed as described previously (Du, Zhu, et al., 2018). The hepatocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Antigen retrieval was performed using EDTA‐Na2 at 95°C. The hepatocytes were permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X‐100. For immunostaining, the cells were incubated with antibodies (as indicated in the figure legends) diluted in PBS containing 5% goat serum overnight at 4°C. The hepatocytes were then incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to FITC and/or Cyanine Cy™3. Subsequently, nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma‐Aldrich). The hepatocytes were observed by laser confocal microscopy (Fluoview FV1200, OLYMPUS). At least 20 random cells were observed from each individual experiment after different treatments. Image‐Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA; RRID:SCR_007369) was used to quantify the signals.

2.8. Analysis of autophagy

Autophagy was measured according to previously described methods (Klionsky et al., 2016). To determine autophagy, the LC3‐II protein was measured by immunoblotting with or without chloroquine. The recombinant adenovirus mRFP‐GFP‐LC3 (1 × 1010 PFU·ml−1) was obtained from Hanbio. Hepatocytes were transfected with the mRFP‐GFP‐LC3 recombinant adenovirus according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then the hepatocytes were treated with or without cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside. After washing with PBS and fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, nuclei were stained with DAPI (D9542; Sigma‐Aldrich). Subsequently, the hepatocytes were observed by laser confocal microscopy (Fluoview FV1200, OLYMPUS, Japan). In recombinant adenovirus mRFP‐GFP‐LC3‐transfected hepatocytes, yellow or red puncta were detected in at least 20 random cells from each individual experiment after different treatments. Image‐Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics) was used to quantify the signals.

2.9. Liver histology

Liver tissue was fixed in 10% formaldehyde neutral buffer solution, embedded in paraffin, cut into 8‐μm sections and stained with H&E. For Oil‐red O staining, liver tissue was frozen in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek Co, Torrance, CA, USA), sectioned at an 8‐μm thickness at −18°C and fixed with 75% alcohol at room temperature for 15 min. Then the slides were stained with Oil‐red O (O0625; Sigma‐Aldrich) and counterstained with haematoxylin.

2.10. Immunohistochemistry

The Immuno‐related procedures used comply with the recommendations made by the British Journal of Pharmacology (Alexander et al., 2018). Briefly, paraffin‐embedded liver sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated in graded alcohol solutions. A heat‐induced epitope retrieval technique was used by boiling liver sections in a solution of 10‐mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. Then the slides were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (AR0009; Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) in PBS for 30 min. The slides were incubated with an antibody diluted in PBS containing 5% goat serum overnight at 4°C. The specificity of staining was examined by omitting the primary antibodies. The slides were subsequently incubated with HRP‐conjugated anti‐rabbit or anti‐mouse IgG at room temperature for 45 min. Finally, the sections were stained with diaminobenzidine and counterstained with haematoxylin and images were acquired (OLYMPUS).

2.11. Western blotting

Liver tissue and hepatocyte total proteins were extracted using a protein extraction kit (C510003; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The total protein concentration was estimated by the BCA method (P1511; Applygen Technologies Inc., Beijing, China). The samples were separated by SDS‐PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membranes were blocked in 3% BSA/Tris‐buffered saline/Tween buffer for 4 h. The blocked membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody. The membranes were then incubated with HRP‐conjugated anti‐rabbit or anti‐mouse IgG at room temperature for 45 min. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence solution (WBKLS0500, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). All bands were analysed using Image‐Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics). Beta‐actin was used as a reference protein in this study. The western blots shown are representative of three independent experiments with consistent results.

2.12. Isolation of mitochondria

Mitochondria were isolated from fresh liver tissue or hepatocytes using a mitochondrion isolation kit (C3606, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Nantong, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, tissues or hepatocytes were homogenized in ice‐cold mitochondria isolation buffer with 1‐mM PMSF and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the supernatants were transferred to another centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 3,500 g for 10 min at 4°C and the sediment was mitochondria. The remaining supernatants were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to obtain the cytoplasmic fraction.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA; RRID:SCR_002798) or SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA; RRID:SCR_002865). Sample size of each protocol was determined on the basis of similar previous studies (Gu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). Group size is the number of independent values and that statistical analysis was done using these independent values. Statistical analysis was undertaken only for studies where each group size was at least n = 5. Statistical significance was calculated using two‐tailed Student's t tests for comparisons between two groups and one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc test adjusted using Bonferroni correction for comparisons among more than two groups. Post hoc tests were run only if F achieved P < 0.05 and there was no significant variance inhomogeneity. To control the unwanted sources of variation, normalization of the data was carried out. The mean values of the control group were normalized to 1. In the figures, the Y axis shows the ratio of the experimental group to that of the corresponding matched control values. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All studies were designed to generate groups of equal size, using randomization and blinded analysis. When outliers were included or excluded in analysis, it was declared within the figure legend. The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations of the British Journal of Pharmacology on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2018).

Other detailed methods are provided in Supporting Information Materials and Methods.

2.14. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al., 2018) are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20 (Alexander et al., 2019).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside ameliorates hepatic lipid accumulation and improves systemic glucose metabolism

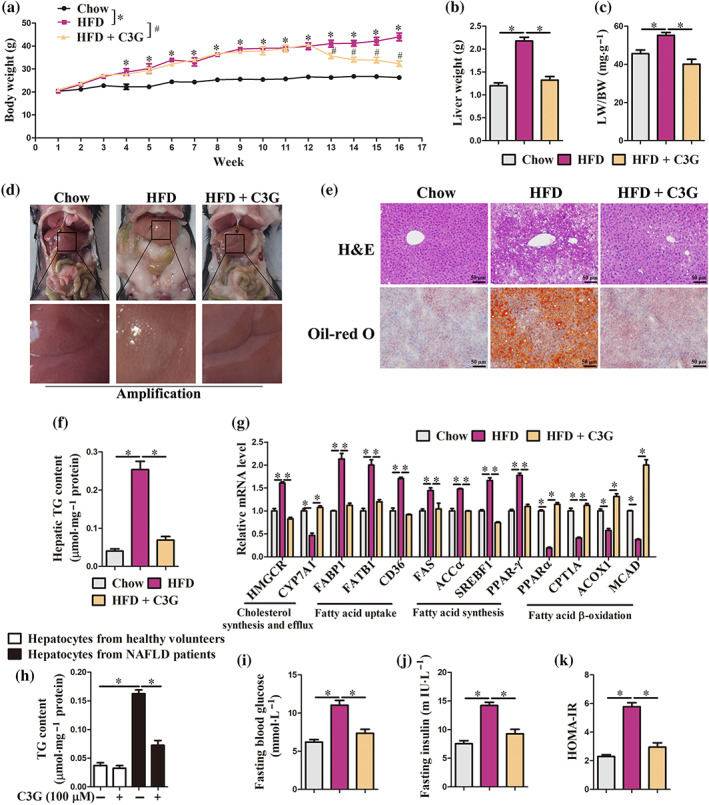

Mice were fed either a chow diet or an high fat diet for 16 weeks. cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐treated mice were fed a high fat diet for 12 weeks and then fed an high fat diet containing 0.2% cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside for another 4 weeks. In high fat diet mice, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside significantly reduced body weight (Figure 1a), liver weight (Figure 1b) and ratio of liver weight to body weight (LW/BW) (Figure 1c). Data from gross anatomy (Figure 1d), H&E and Oil‐red O staining (Figure 1e) and triglyceride analysis (Figure 1f) revealed that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside treatment markedly alleviated hepatic steatosis in high fat diet mice. Furthermore, the mRNA abundance of cholesterol synthesis‐related genes (HMGCR), fatty acid uptake‐related genes (FABP1, FATB1 and CD36) and fatty acid synthesis‐related genes (FAS, ACCα, SREBF1 and PPAR‐γ) was down‐regulated, whereas the mRNA abundance of cholesterol efflux‐related genes (CYP7A1) and fatty acid β‐oxidation‐related genes (Ppara, CPT1A, ACOX1 and MCAD) was up‐regulated in high fat diet + cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside mice compared with high fat diet mice (Figure 1g). In vitro, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (10–400 μM) exhibited no cytotoxic activity (Figure S2A–D) and 100‐μM cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside alleviated palmitic acid‐induced lipid accumulation in AML‐12 cells (Figure S2E,F). In hepatocytes from non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease patients, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside markedly decreased triglyceride content (Figure 1h). Besides, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside decreased the fasting glucose and insulin levels and HOMA‐IR indexes in high fat diet mice (Figure 1i–k). These data indicate that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside ameliorates hepatic lipid accumulation and improves systemic glucose metabolism in an high fat diet condition.

FIGURE 1.

Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G) ameliorates hepatic steatosis and improves systemic glucose metabolism. (a–g, i–k) Mice were fed either a chow diet or an high fat diet fat (HFD) or 16 weeks. C3G‐treated mice were fed an high fat diet for 12 weeks and then fed an high fat diet containing 0.2% C3G for another 4 weeks (n = 9 mice per group). (a–c) Body weight, liver weight and LW/BW ratio. (d) Gross anatomical views of representative mouse liver. (e) Representative images of H&E and Oil‐red O staining of liver sections (original magnification 20×). (f) Hepatic triglyceride content. (g) mRNA abundance of genes related to cholesterol synthesis and efflux and fatty acid uptake, synthesis and β‐oxidation in the liver. (h) triglyceride content in hepatocytes from healthy controls and patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Hepatocytes were treated with or without 100‐μM C3G for 12 h (n = 6). (i, j) Fasting blood glucose and insulin levels. (k) HOMA‐IR indexes. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05; # P < 0.05

3.2. Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation in hepatocytes

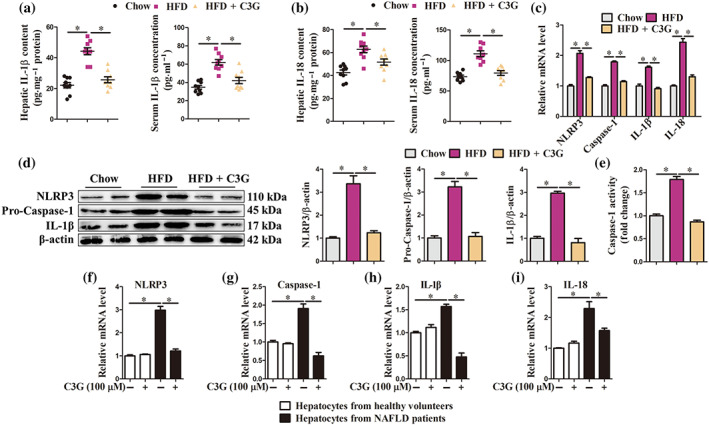

Patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease display low‐grade chronic inflammation, whereas suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation mitigates hepatic steatosis and ameliorates glucose homeostasis (Wan et al., 2016). In the present study, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside administration markedly reduced hepatic and blood levels of IL‐1β and IL‐18 (Figure 2a,b), mRNA abundance of NLRP3, Caspase 1, IL‐1β and IL‐18 (Figure 2c) and protein abundance of NLRP3, Pro‐Caspase‐1 and IL‐1β (Figure 2d) in the livers of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, which induced by high fat diet. Furthermore, we also observed decreased activity of Caspase 1 in the livers of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐treated non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice (Figure 2e). Palmitic acid‐induced lipotoxicity has been implicated in NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Huang et al., 2012; Moon et al., 2016; Robblee et al., 2016). We found that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside reduced IL‐1β and IL‐18 content in supernatants and cell lysates of palmitic acid‐treated AML‐12 cells (Figure S3). Furthermore, in hepatocytes from non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease patients, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside markedly decreased mRNA abundance of NLRP3, Caspase 1, IL‐1β and IL‐18 (Figure 2f–i). These data indicate that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation in vivo and in vitro.

FIGURE 2.

Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G) inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation. (a–e) Mice were treated as described in Figure 1 (n = 9 mice per group). (a, b) Content of IL‐1β and IL‐18 in the livers and blood from different groups. (c–e) mRNA abundance of NLRP3, Caspase‐1, IL‐1β and IL‐18, the protein abundance of NLRP3, Pro‐caspase‐1 and IL‐1β and the activity of Caspase‐1 in the livers from different groups. (f–i) mRNA abundance of NLRP3, Caspase‐1, IL‐1β and IL‐18 in hepatocytes from healthy controls and patients with NAFLD. Hepatocytes were treated with or without 100‐μM C3G for 12 h (n = 6). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

3.3. Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside attenuates oxidative stress and eliminates damaged mitochondria

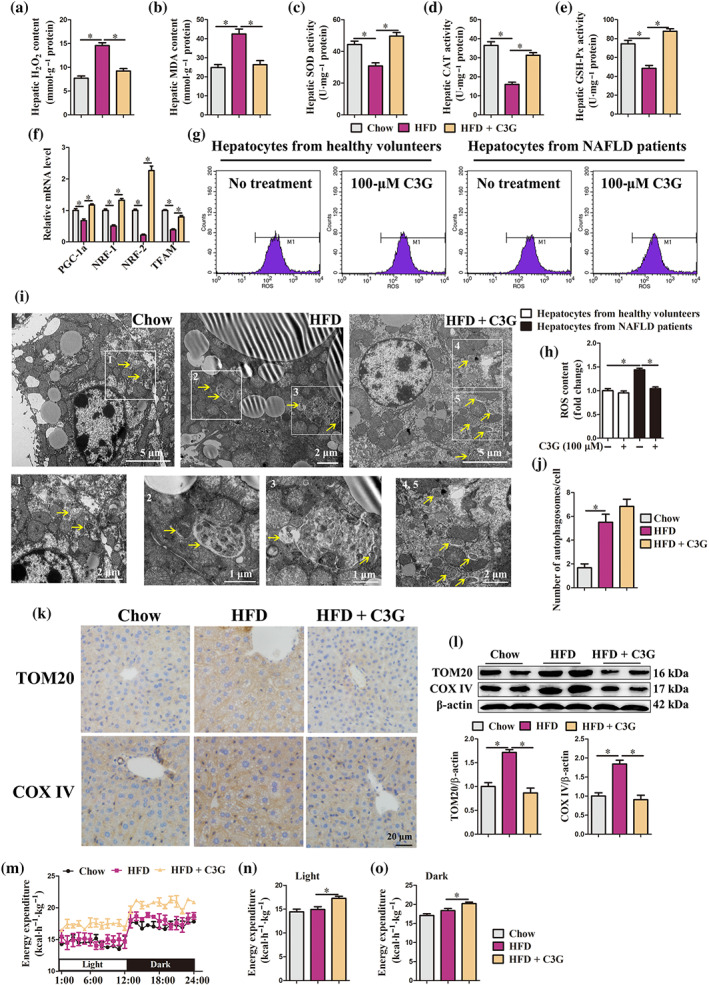

Overloaded fatty acids exert lipotoxicity effects on mitochondria, leading to mitochondria dysfunction and oxidative stress, thereby further exacerbating steatosis in the liver (Begriche et al., 2013). Our results revealed that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside reduced H2O2 and MDA content (Figure 3a,b) and elevated SOD, l‐cysteine:2‐oxoglutarate aminotransferase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH‐Px) activities (Figure 3c–e) in the livers of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Besides, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside up‐regulated the mRNA abundance of mitochondrial function regulators peroxisome proliferative activated receptor‐ γ (NR1C3), nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1), nuclear factor erythroid derived 2 like 2 (NRF2) and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) in the livers of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Figure 3f). In vitro, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside treatment significantly reduced ROS content in palmitic acid ‐treated AML‐12 cells (Figure S4), as well as hepatocytes from non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease patients (Figure 3g,h). These data demonstrate that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside attenuates oxidative stress of hepatocytes.

FIGURE 3.

Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G) attenuates hepatic oxidative stress and clears damaged mitochondria. (a–f, i–o) Mice were treated as described in Figure 1 (n = 9 mice per group). (a–e) H2O2 and MDA content, activities of SOD, CAT and GSH‐Px in the livers from different groups. (f) mRNA abundance of PGC‐1α, NRF‐1, NRF‐2 and TFAM in the livers from different groups. (g, h) ROS content in hepatocytes from healthy controls and patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Hepatocytes were treated with or without 100‐μM C3G for 12 h (n = 6). (i) Representative TEM images of the liver. Autophagosomes (arrow). (j) Number of autophagosomes in the TEM images of the liver. (k) Hepatic protein abundance of TOM20 and COX IV in the livers from different groups. (l) Representative images of hepatic IHC staining for TOM20 and COX IV (original magnification 40×). (m–o) Energy expenditure in different groups. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

In the livers of patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, the mitochondria displayed a swollen morphology and crest rupture (Figures S5 and 3i). Interestingly, the protein abundance of two mitochondrial markers TOM20 and COX IV were higher in the livers of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Figure 3k,l), as well as hepatocytes from non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease patients (Figure 4e), than corresponding controls. These data suggest that damaged mitochondria accumulate in the livers of patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, which further induces oxidative stress. Importantly, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside reduced TOM20 and COX IV protein abundance in the livers of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice (Figure 3k,l) and hepatocytes from non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease patients (Figure 4e), implying that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside eliminates damaged mitochondria to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and alleviate oxidative stress.

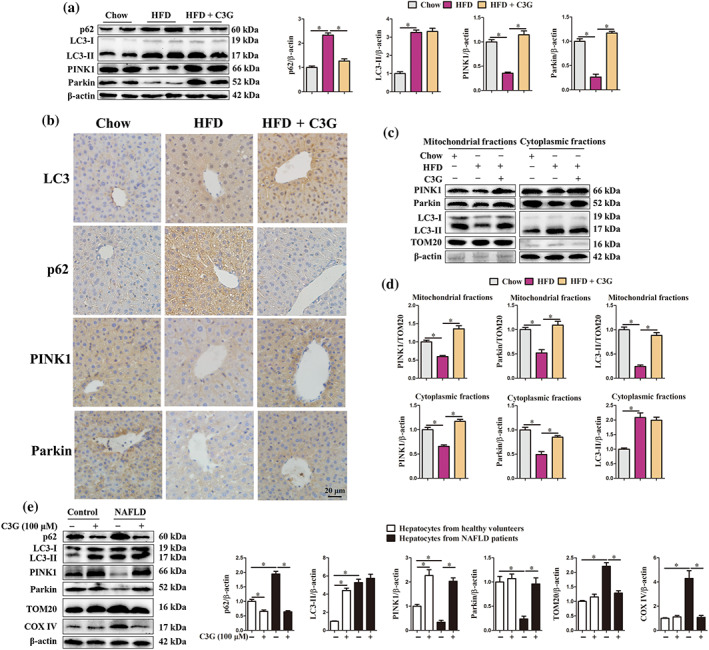

FIGURE 4.

Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G) restores ) high fat diet (HFD)‐impaired hepatic mitophagy. (a–d) Mice were treated as described in Figure 1 (n = 9 mice per group). (a) Protein abundance of p62, LC3, PINK1 and Parkin in the livers from different groups. (b) Representative images of hepatic IHC staining for LC3, p62, PINK1 and Parkin in different groups (original magnification 40×). (c, d) Protein levels of PINK1, Parkin and LC3 in mitochondrial or cytoplasmic fractions of the livers from different groups. (e) Protein abundance of p62, LC3, PINK1, Parkin, TOM20 and COX IV in hepatocytes from healthy controls and patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Hepatocytes were treated with or without 100‐μM C3G for 12 h (n = 6). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

Of note, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside administration significantly increased the overall energy expenditure of high fat diet mice in both light and dark (Figure 3m–o). Nevertheless, food intake was comparable between high fat diet mice treatment with or without cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (Figure S6A) and cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside did not alter the physical activity during either day or night (Figure S6B–D). Total energy expenditure in animals is a sum of energy utilization during physical activity and internal heat production. Therefore, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside enhanced the heat production in high fat diet mice, which may result from cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside improved mitochondrial homeostasis.

3.4. The hepatic autophagy and mitophagy is impaired in patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

Impaired mitochondria produce excessive ROS, which induce oxidative stress and disturb mitochondrial homeostasis (Zhong et al., 2016). Autophagy can target and selectively eliminate the damaged mitochondria, also known as mitophagy and this process is triggered by PINK1–Parkin cascade (Williams, Ni, Ding, & Ding, 2015). In the present study, we found significantly higher number of autophagosomes (Figures 3i,j and S5) and protein abundance of p62 and LC3‐II (Figure 4a,b,e) in the livers of mice and patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease than in the corresponding controls. Conversely, the protein abundance of mitophagy initiators PINK1 and Parkin was lower in the livers of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Figure 4a,b) and in hepatocytes from non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease patients (Figure 4e). More importantly, compared with control mice, the protein abundance of PINK1, Parkin and LC3‐II in the hepatic mitochondrial fraction from non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice was significantly reduced (Figure 4c,d). Taken together, these data indicate that PINK1–Parkin‐dependent mitophagy is blocked in the livers of patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease.

3.5. Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside enhances PINK1–Parkin‐dependent mitophagy in the livers of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

In vitro, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside significantly up‐regulated the mRNA abundance of autophagosome formation genes, including PI3K catalytic subunit type 3 (PIK3C3), beclin 1 (BECN1), ATG5, ATG12, ATG7, transcription factor EB (TFEB) and LC3, in AML‐12 cells (Figure S7A). When autophagic flux was inhibited by chloroquine, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside significantly promoted the accumulation of p62 and LC3‐II in AML‐12 cells (Figure S7B). Besides, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside markedly increased the number of autophagosomes labelled with yellow puncta and autolysosomes labelled with red puncta (Figure S7C,D). These data indicate that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside enhances autophagic flux in hepatocytes.

Considering the clearance of damage mitochondria and autophagic induction effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside, we speculated that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside might improve the impaired hepatic mitophagy in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice. Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside treatment increased hepatic mRNA abundance of autophagosome formation genes in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice (Figure S8). Despite the absence of differences in number of autophagosomes (Figure 3i,j) and LC3‐II protein abundance (Figure 4a,b), the abundance of p62 (Figure 4a,b) was significantly reduced in the livers of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐treated non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice, implying that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside restored the blocked autophagy. Importantly, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside significantly increased total protein abundance of PINK1 and Parkin, the initiators of mitophagy, in the livers of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Figure 4a,b) and in hepatocytes from non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease patients (Figure 4e). Furthermore, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside enhanced PINK1, Parkin and LC3‐II protein abundance in hepatic mitochondrial fraction of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Figure 4c,d). These data strongly indicate that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside elevates hepatic PINK1–Parkin‐dependent mitophagy in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease condition.

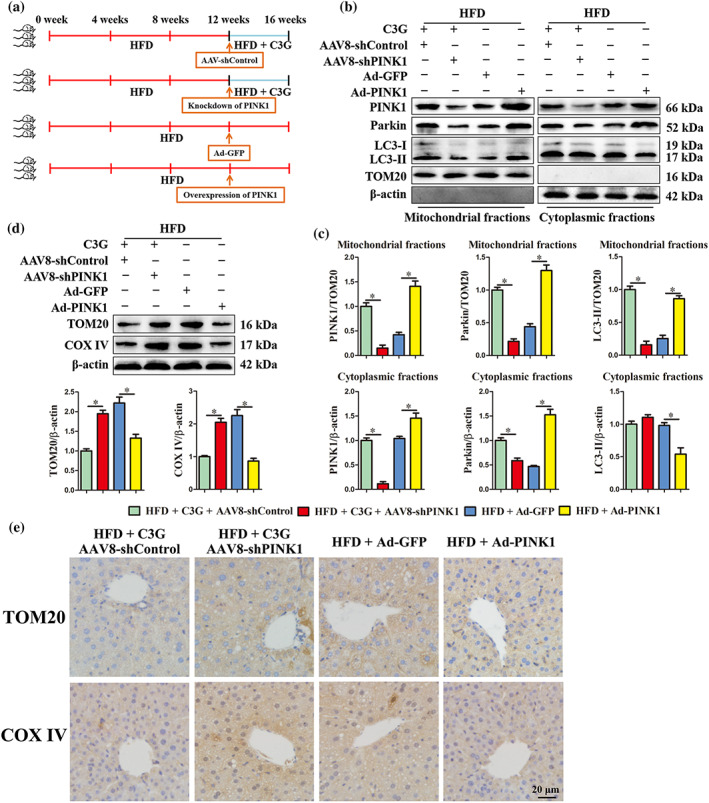

3.6. Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside induces PINK1‐mediated mitophagy in vivo and in vitro

Next, we explored whether cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐induced mitophagy was mediated by PINK1. Knockdown of PINK1 by using AAV8‐shPINK1 in cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐treated high fat diet mice (Figure 5a) significantly reduced cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐increased PINK1, Parkin and LC3‐II protein levels in hepatic mitochondrial fraction (Figure 5b,c). Meanwhile, PINK1 knockdown abolished the clearance ability of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside for damaged mitochondria, as evidenced by increased protein abundance of TOM20 and COX IV evaluated by western blot and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Figure 5d,e). Accordingly, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside scavenges the dysfunctional mitochondria by promoting PINK1‐mediated mitophagy in the liver of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice. Besides, overexpression of PINK1 in the livers of high fat diet mice partially enhanced the mitophagy (Figure 5b,c) and decreased the mitochondria content (Figure 5d,e), which further imply that the beneficial effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside result from PINK1‐mediated mitophagy.

FIGURE 5.

Knockdown of PINK1 blocks cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G)‐induced hepatic mitophagy. (a) Schematic of the experimental design. (b–e) Mice were treated as shown in Figure 6a (n = 9 mice per group). (b, c) Protein levels of PINK1, Parkin and LC3 in mitochondrial or cytoplasmic fractions of the livers from different groups. (d) Hepatic protein abundance of TOM20 and COX IV in the livers from different groups. (e) Representative images of hepatic IHC staining for TOM20 and COX IV in different groups (original magnification 40×). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

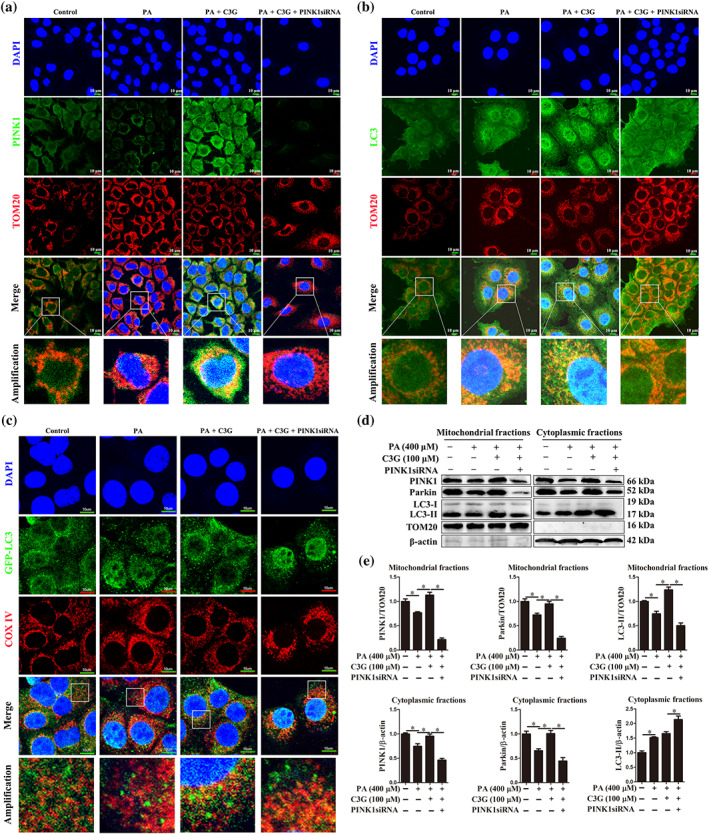

Mitochondrial outer membrane protein TOM20 and inner membrane protein COX IV are markers for mitochondrion and their colocalization with PINK1 or LC3 represents the happening of mitophagy (Bingol & Sheng, 2016; Klionsky et al., 2016; McWilliams & Muqit, 2017). Our result revealed that palmitic acid decreased the colocalization of PINK1 and TOM20 in AML‐12 cells (Figure 6a). Nevertheless, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside treatment restored palmitic acid‐impaired colocalization of PINK1 and TOM20; however, PINK1 knockdown blunted the beneficial effect of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (Figure 6a). Besides, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside enhanced the colocalization of LC3 and TOM20 (Figure 6b), GFP‐LC3 and COX IV (Figure 6c), which blocked by knockdown of PINK1 (Figure 6b,c). Moreover, the PINK1, Parkin and LC3 protein levels in the mitochondrial fraction were decreased, which were restored by cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside, in palmitic acid‐treated HepG2 cells (Figure 6d,e). Whereas, knockdown of PINK1 lowered the protein abundance of Parkin and LC3 in mitochondrion fraction, even in the presence of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (Figure 6d,e). These results indicate that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside promotes PINK1‐mediated mitophagy in vitro.

FIGURE 6.

Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G) induces mitophagy via PINK1 in hepatocytes. (a, b) Representative images of PINK1 and TOM20, LC3 and TOM20 immunofluorescence staining in AML‐12 cells (n = 6). (c) Representative images of GFP‐LC3 and COX IV immunofluorescence staining in AML‐12 cells (n = 6). (d, e) Protein levels of PINK1, Parkin and LC3 in mitochondrial or cytoplasmic fractions in HepG2 cells (n = 6). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

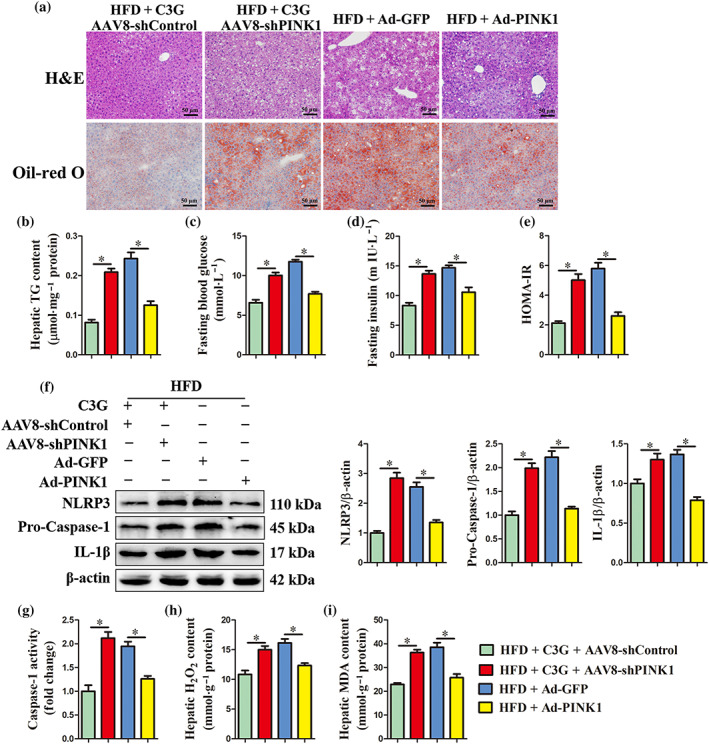

3.7. PINK1‐mediated mitophagy is required for the beneficial effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside administration could improve non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease through eliminating hepatic steatosis, reducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation and oxidative stress and improving systemic glucose metabolism. Given the potential role of mitophagy in hepatic metabolism homeostasis and the enhancement of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on PINK1‐dependent mitophagy, the beneficial effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease may be mediated by PINK1‐dependent mitophagy. To test this speculation, AAV8‐shPINK1 was used to block hepatic PINK1‐dependent mitophagy. Mice were fed an high fat diet and treated as shown in Figure 5a. Knockdown of PINK1 reversed the improvement effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on hepatic steatosis (Figure 7a,b) and systemic glucose metabolism in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice (Figure 7c–e). Besides, the suppressive effect of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on hepatic NLRP3 inflammasome (Figure 7f,g) and the antioxidant effect (Figure 7h,i) in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice was also blocked by PINK1 knockdown. These findings demonstrate that the beneficial effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease require PINK1‐mediated mitophagy. Moreover, we also found that ectopic expression of PINK1 partially alleviated high fat diet‐induced non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Figure 7), which further indicate that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside activates PINK1‐mediated mitophagy to protect mice from high fat diet‐induced non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease.

FIGURE 7.

PINK1‐mediated mitophagy is required for the beneficial effects of C3G on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Mice were treated as shown in Figure 6a (n = 9 mice per group). (a) Representative images of H&E and Oil‐red O staining of liver sections (original magnification 20×). (b) Hepatic triglyceride (TG) content in the indicated groups. (c, d) Fasting blood glucose and insulin levels. (e) HOMA‐IR indexes. (f, g) Protein abundance of NLRP3, Pro‐Caspase‐1 and IL‐1β and the activity of Caspase‐1 in the livers from different groups. (h, i) H2O2 and MDA content in the livers from different groups. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

4. DISCUSSION

Here, we found that hepatic mitophagy was blocked in patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease by cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside. More importantly, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside targeted PINK1‐mediated mitophagy and further ameliorated hepatic oxidative stress, NLRP3 inflammasome activation and steatosis and improved glucose metabolism in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice. Accordingly, our results demonstrate that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside may be an attractive potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease.

The hallmark histological feature of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease is hepatic steatosis; moreover, the consequential surplus of lipids in hepatocytes result in oxidative stress and inflammation (Begriche et al., 2013). This ‘two hit theory’ is widely accepted to explain the pathogenesis of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Furthermore, these mechanisms interact with each other and collectively aggravate the development of fatty liver, ultimately resulting in liver injury (Begriche et al., 2013). In recent years, it was well reported that autophagy and hepatic lipid metabolism were interrelated and autophagic dysfunction was involved in the ‘two hit’ process (Gonzalez et al., 2014; Ling, Ping, Suneng, Calay, & Hotamisligil, 2010). Singh et al. (2009) reported that autophagy regulated lipid metabolism by eliminating triglyceride and further prevented the development of hepatic steatosis. Meanwhile, autophagy deficiency induced oxidative stress and promoted NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Madrigal & Cuervo, 2016; Zhong et al., 2016). In this study, impaired autophagic flux accompanied by oxidative stress and over‐activated NLRP3 inflammasome were observed in the liver of patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, which were consistent with previous work that reported that impaired hepatic autophagy is associated with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Gonzalez et al., 2014; Tanaka et al., 2016).

Although no effective drug therapy for non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease has been established yet, compounds derived from dietary are emerging as potential therapeutics against non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease due to high efficacy and low risk of side effects (Van, Koek, Bast, & Haenen, 2017). Increasing evidence showed that flavonoids could be used in the treatment of obesity and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Salomone, Godos, & Zelber, 2016; Van et al., 2017), such as cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (Jeon et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2012), whereas the potential action mechanisms remain vague, which limit its clinical application. In our study, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside alleviated hepatic steatosis, reduced hepatic oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation and improved systemic glucose metabolism in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice. More importantly, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside restored autophagy flux in the liver of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Given the suppression effects of autophagy on oxidative stress, inflammation and steatosis (Ling et al., 2010; Madrigal & Cuervo, 2016; Zhong et al., 2016), autophagy, therefore, may mediate the positive role of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice.

In this study, up‐regulated transcription factors TFEB and PPARα and autophagy‐related genes were observed in cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐treated non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice. TFEB is a master regulator of autophagy‐related gene transcription and lysosome biogenesis (Perera, Di, & Ballabio, 2019) and PPARα activation was reported to up‐regulate the autophagy‐related genes expression (Lee et al., 2014). Therefore, TFEB and PPARα play overlapping roles in transcriptional control of the autophagy‐related gene network (Iershov et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2017; Settembre et al., 2013) and cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐induced autophagy may result from enhanced activities of TFEB and PPARα. Interestingly, in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice, the hepatic protein abundance of LC3‐II and number of autophagosomes were not altered by cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside. In fact, in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice, autophagosome degradation was blocked, which resulted in the accumulation of autophagosomes, LC3‐II and p62. Nevertheless, in cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐treated non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice, decreased protein abundance of p62 indicated that the blocked autophagosome degradation was restored. Meanwhile, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside up‐regulated the expression of autophagosome formation genes and further resulted in the elevation of LC3‐II protein abundance and formation of autophagosomes. Accordingly, the autophagosome formation and degradation achieved a dynamic balance in the liver of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐treated non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice, leading to the LC3‐II protein abundance and autophagosomes number was comparable between non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice treated with or without cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside.

By examining ultrastructural characteristics and the mitochondria content markers, we observed that the excessively damaged mitochondria were accumulated in the livers of patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Excessive dysfunctional mitochondria release large amounts of ROS, a common predisposing cause of pathological mechanisms in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, which directly induce oxidative stress and activate NLRP3 inflammasome, thereby exacerbating hepatic steatosis (Murata et al., 2015). Therefore, clearance of damaged mitochondria may play a crucial role in improvement of NAFLD. Autophagy is essential for the control of mitochondrial quality, namely, mitophagy, that efficiently scavenges impaired mitochondria (Lazarou et al., 2015; McWilliams & Muqit, 2017). Unfortunately, our data showed that the total protein abundance of PINK1 and Parkin, key activators of mitophagy, was decreased in the livers of patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Importantly, the mitochondrial protein abundance of PINK1, Parkin and LC3‐II was also decreased in the liver of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice and in palmitic acid‐treated hepatocytes, indicating blocked initiation of PINK1‐mediated mitophagy. Fortunately, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside increased the expression and mitochondrial localization of PINK1, Parkin and LC3 in the livers of mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and in palmitic acid‐treated hepatocytes, indicating that the blocked mitophagy was restored by cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside. Importantly, knockdown of PINK1 diminished the beneficial role of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on PINK1‐mediated mitophagy, which further blocked the improvement effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on hepatic oxidative stress, NLRP3 inflammasome, steatosis and glucose metabolism in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease mice. These findings indicate that PINK1‐mediated mitophagy is required for the beneficial effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Furthermore, impaired mitophagy may be a critical factor of ‘the second hit’ during the development of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and acceleration of mitophagy by targeting PINK1 may represent a promising and effective strategy for non‐alcoholic lipid liver disease therapy.

Breakdown of lipid droplets by autophagy, namely, lipophagy, release free fatty acids that can be transported into mitochondria for β‐oxidation (Schulze, Drižytė, Casey, & McNiven, 2017). Our results revealed that the up‐regulated mRNA abundance of β‐oxidation genes and decreased lipid droplets were associated with cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐induced autophagy, indicating that cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside may degrade lipid droplets by inducing lipophagy. Therefore, cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside‐induced lipophagy and mitophagy may cooperate to decrease hepatic lipid accumulation, which also indicate that the beneficial effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease are multifarious. Given the complexity of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease pathogenesis, multiple pathological factors participate in the occurrence and development of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Therefore, compared with uni‐target drugs, multi‐target drugs may be more effective for the treatment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (Salomone et al., 2016; Van et al., 2017). Therefore, mechanistic investigations and clinical studies are needed to determine the multi‐target effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside on the treatment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease.

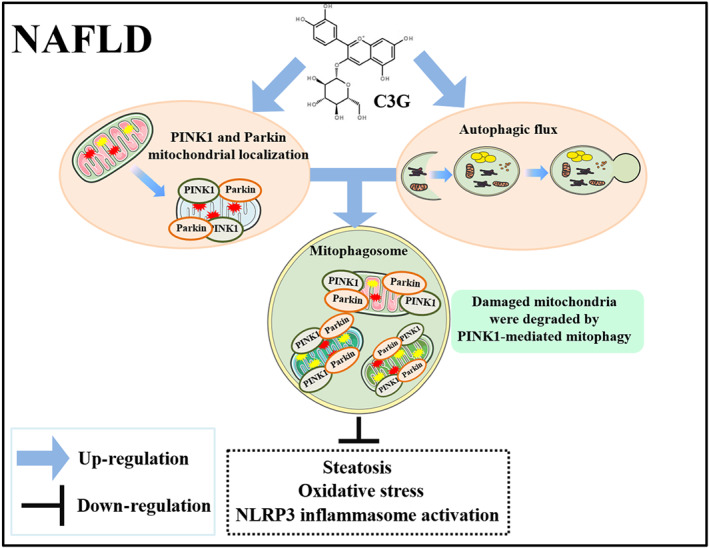

We demonstrate, for the first time to our knowledge, that mitophagy is impaired in the liver of patients and mice with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside enhances autophagic flux, increases PINK1/Parkin expression and mitochondrial localization and subsequently induces mitophagy to degrade damaged mitochondria and decrease ROS production, which exerts further beneficial effects on NLRP3 inflammasome activation and steatosis (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Proposed model for the beneficial effects of cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside (C3G) on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). C3G up‐regulated PINK1 and Parkin expression, which localized on damaged mitochondrial and enhanced autophagic flux simultaneously. Subsequently, damaged mitochondrial was engulfed by mitophagosome and degraded by mitophagolysosome, which further ameliorates hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.L.D. and G.W.L. designed and supervised the study. X.W.L. and Z.S. performed the experiments, prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. G.H.S. and J.J.L. contributed to the editing of the manuscript. Y.W.Z., T.Y.S. and H.Y.W. contributed to the collection of serum samples and the clinical analysis. Z.Y.F. and M.C. provided great helps for the laboratory technique, experiments and data analysis. X.H.W., Z.C.P. and Z.W. performed the statistical analyses. All authors reviewed and revised the final version of this manuscript and approved its submission.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors have followed the recommendations set out in the BJP editorials.

DECLARATION OF TRANSPARENCY AND SCIENTIFIC RIGOUR

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research as stated in the BJP guidelines for Design and Analysis, Immunoblotting and Immunochemistry and Animal Experimentation, and as recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organizations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Chemical structure of C3G

Figure S2. The effects of C3G on cell viability and lipid accumulation. (A, B) Cell viability. AML‐12 and HepG2 cells were treated with 100 μM C3G for 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72 or 96 h. (C, D) Cell viability. AML‐12 and HepG2 cells were treated with 0, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 or 400 μM C3G for 12 h. (E, F) The TG content and representative images of Oil‐red O (original magnification 40×) staining in AML‐12 cells. AML‐12 cells were maintained in medium containing 2% BSA and treated with 400 μM palmitic acid for 12 h, then treated with or without 50 μM chloroquine for 4 h, followed by 12 h post‐treatment with or without 100 μM C3G for 12 h. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05

Figure S3. The effects of C3G on palmitic acid‐induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. AML‐12 cells were maintained in medium containing 2% BSA and treated with palmitic acid for 12 h, then treated with or without C3G for 12 h. (A) Content of IL‐1β in cell lysates and supernatant of AML‐12 cells. (B) Content of IL‐18 in cell lysates and supernatant of AML‐12 cells. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05

Figure S4. The effects of C3G on oxidative stress in AML‐12 cells. AML‐12 cells were maintained in medium containing 2% BSA and treated with palmitic acid for for 12 h, then treated with or without C3G for 12 h. (A, B) ROS content in AML‐12 cells. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05

Figure S5. Representative hepatic TEM images of healthy controls and patients with NAFLD. Autophagosomes (arrow). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05

Figure S6. Food intake and physical activity. (A) Food intake in different groups (n = 9 mice/group). (B‐D) Physical activity in different groups (n = 9 mice/group). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

Figure S7. C3G enhances autophagic flux in AML‐12 cells. (A) The mRNA expression of autophagy‐related genes in AML‐12 cells. AML‐12 cells were treated with 100 μM C3G for 12 h. (B) Protein abundance of p62 and LC3 in AML‐12 cells (n = 6). AML‐12 cells were treated with C3G for 12 h and then treated with or without chloroquine for 4 h. (C) Representative images of autophagosomes (yellow puncta) and autolysosomes (red puncta) (n = 6). AML‐12 cells were transfected with recombinant adenovirus mRFP‐GFP‐LC3 and then treated with C3G. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

Figure S8. Hepatic mRNA abundance of autophagy‐related genes. Mice were fed either a chow diet or a HFD for 16 weeks. C3G‐treated mice were fed a HFD for 12 weeks and then fed a HFD containing 0.2% C3G for another 4 weeks. (n = 9 mice/group). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

Table S1. The baseline characteristics of controls and NAFLD subjects. Values are mean ± SEM

Table S2. The primers sequences used for qRT‐PCR

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Pro. Han‐Ming SHEN (NUS Graduate School for Integrative Sciences and Engineering, National University of Singapore, Singapore) for his valuable suggestions and great assistance during manuscript preparation. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (Beijing, China; Grant 2016YFD0501206), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Beijing, China; Grants 31672621 and 31772810), the ‘Talents Cultivation Program’ of Jilin University and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019TQ0115 and 2019M661216).

Li X, Shi Z, Zhu Y, et al. Cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside improves non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease by promoting PINK1‐mediated mitophagy in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:3591–3607. 10.1111/bph.15083

Contributor Information

Xiliang Du, Email: duxiliang@jlu.edu.cn.

Guowen Liu, Email: liuguowen2008@163.com.

REFERENCES

- Alexander, S. P. , Christopoulos, A. , Davenport, A. P. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , … Pawson, A. J. (2019). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein‐coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S21–S141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Roberts, R. E. , Broughton, B. R. S. , Sobey, C. G. , George, C. H. , Stanford, S. C. , … Ahluwalia, A. (2018). Goals and practicalities of immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry: A guide for submission to the British Journal of Pharmacology . British Journal of Pharmacology, 175, 407–411. 10.1111/bph.14112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo, P. , Kleiner, D. E. , Dam‐Larsen, S. , Adams, L. A. , Bjornsson, E. S. , Charatcharoenwitthaya, P. , … Haflidadottir, S. (2015). Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long‐term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology, 149, 389–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backues, S. K. , Chen, D. , Ruan, J. , Xie, Z. , & Klionsky, D. J. (2014). Estimating the size and number of autophagic bodies by electron microscopy. Autophagy, 10, 155–164. 10.4161/auto.26856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begriche, K. , Massart, J. , Robin, M. A. , Bonnet, F. , & Fromenty, B. (2013). Mitochondrial adaptations and dysfunctions in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology, 58, 1497–1507. 10.1002/hep.26226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingol, B. , & Sheng, M. (2016). Mechanisms of mitophagy: PINK1, Parkin, USP30 and beyond. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 100, 210–222. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt, E. M. , Kleiner, D. E. , Wilson, L. A. , Belt, P. , & Neuschwander‐Tetri, B. A. (2011). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: Distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology, 53, 810–820. 10.1002/hep.24127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, M. , Lai, Y. C. , Romero, Y. , Brands, J. , St Croix, C. M. , Kamga, C. , … Mora, A. L. (2015). PINK1 deficiency impairs mitochondrial homeostasis and promotes lung fibrosis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 125, 521–538. 10.1172/JCI74942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherra, S. J. , Dagda, R. K. , Tandon, A. , & Chu, C. T. (2009). Mitochondrial autophagy as a compensatory response to PINK1 deficiency. Autophagy, 5, 1213–1214. 10.4161/auto.5.8.10050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M. J. , Alexander, S. , Cirino, G. , Docherty, J. R. , George, C. H. , Giembycz, M. A. , … Ahluwalia, A. (2018). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting II: Updated and simplified guidance for authors and peer reviewers. British Journal of Pharmacology, 175, 987–993. 10.1111/bph.14153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M. J. , Bond, R. A. , Spina, D. , Ahluwalia, A. , Alexander, S. P. , Giembycz, M. A. , … McGrath, J. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: New guidance for publication in BJP . British Journal of Pharmacology, 172, 3461–3471. 10.1111/bph.12856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, X. , Shen, T. , Wang, H. , Qin, X. , Xing, D. , Ye, Q. , … Peng, Z. (2018). Adaptations of hepatic lipid metabolism and mitochondria in dairy cows with mild fatty liver. Journal of Dairy Science, 101, 9544–9558. 10.3168/jds.2018-14546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, X. , Zhu, Y. , Peng, Z. , Cui, Y. , Zhang, Q. , Shi, Z. , … Li, X. (2018). High concentrations of fatty acids and beta‐hydroxybutyrate impair the growth hormone‐mediated hepatic JAK2‐STAT5 pathway in clinically ketotic cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 101, 3476–3487. 10.3168/jds.2017-13234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvano, F. , La Fauci, L. , Lazzarino, G. , Fogliano, V. , Ritieni, A. , Ciappellano, S. , … Galvano, G. (2004). Cyanidins: Metabolism and biological properties. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 15, 2–11. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2003.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, R. A. , Mayoral, R. , Agra, N. , Valdecantos, M. P. , Pardo, V. , Miquilena, C. M. E. , … Piacentini, M. (2014). Impaired autophagic flux is associated with increased endoplasmic reticulum stress during the development of NAFLD. Cell Death & Disease, 5, e1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M. , Zhang, Y. , Liu, C. , Wang, D. , Feng, L. , Fan, S. , … Huang, C. (2017). Morin, a novel liver X receptor α/β dual antagonist, has potent therapeutic efficacy for nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174, 3032–3044. 10.1111/bph.13933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H. , Xia, M. , Zou, T. , Ling, W. , Zhong, R. , & Zhang, W. (2012). Cyanidin 3‐glucoside attenuates obesity‐associated insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in high‐fat diet‐fed and db/db mice via the transcription factor FoxO1. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 23, 349–360. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. D. , Sharman, J. L. , Faccenda, E. , Southan, C. , Pawson, A. J. , Ireland, S. , … NC‐IUPHAR . (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: Updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, D1091–D1106. 10.1093/nar/gkx1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. , Rutkowsky, J. M. , Snodgrass, R. G. , Ono, M. K. D. , Schneider, D. A. , Newman, J. W. , … Hwang, D. H. (2012). Saturated fatty acids activate TLR‐mediated proinflammatory signaling pathways. Journal of Lipid Research, 53, 2002–2013. 10.1194/jlr.D029546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iershov, A. , Nemazanyy, I. , Alkhoury, C. , Girard, M. , Barth, E. , Cagnard, N. , … Pende, M. (2019). The class 3 PI3K coordinates autophagy and mitochondrial lipid catabolism by controlling nuclear receptor PPARα. Nature Communications, 10, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, S. , Han, S. , Lee, J. , Hong, T. , & Yim, D. S. (2012). The safety and pharmacokinetics of cyanidin‐3‐glucoside after 2‐week administration of black bean seed coat extract in healthy subjects. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol, 16, 249–253. 10.4196/kjpp.2012.16.4.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny, C. , Browne, W. , Cuthill, I. C. , Emerson, M. , Altman, D. G. , & Group NCRRGW . (2010). Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: The ARRIVE guidelines. British Journal of Pharmacology, 160, 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. S. , Lee, H. M. , Kim, J. K. , Yang, C. S. , Kim, T. S. , Jung, M. , … Jo, E. K. (2017). PPAR‐α activation mediates innate host defense through induction of TFEB and lipid catabolism. The Journal of Immunology, 198(8), 3283–3295. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky, D. J. , Abdelmohsen, K. , Abe, A. , Abedin, M. J. , Abeliovich, H. , & Acevedo, A. A. (2016). Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy, 12, 1–222. 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliaki, C. , Szendroedi, J. , Kaul, K. , Jelenik, T. , Nowotny, P. , Jankowiak, F. , … Roden, M. (2015). Adaptation of hepatic mitochondrial function in humans with non‐alcoholic fatty liver is lost in steatohepatitis. Cell Metabolism, 21, 739–746. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S. H. , Ahn, I. S. , Kim, S. O. , Kong, C. S. , Chung, H. Y. , Do, M. S. , & Park, K. Y. (2007). Anti‐obesity and hypolipidemic effects of black soybean anthocyanins. Journal of Medicinal Food, 10, 552–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarou, M. , Sliter, D. A. , Kane, L. A. , Sarraf, S. A. , Wang, C. , Burman, J. L. , … Youle, R. J. (2015). The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature, 524, 309–314. 10.1038/nature14893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCluyse, E. L. , Alexandre, E. , Hamilton, G. A. , Viollon, A. C. , Coon, D. J. , Jolley, S. , & Richert, L. (2005). Isolation and culture of primary human hepatocytes. Methods in Molecular Biology, 290, 207–229. 10.1385/1-59259-838-2:207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. M. , Wagner, M. , Xiao, R. , Kim, K. H. , Feng, D. , Lazar, M. A. , & Moore, D. D. (2014). Nutrient‐sensing nuclear receptors coordinate autophagy. Nature, 2014(516), 112–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Y. , Ping, L. , Suneng, F. , Calay, E. S. , & Hotamisligil, G. K. S. (2010). Defective hepatic autophagy in obesity promotes ER stress and causes insulin resistance. Cell Metabolism, 11, 467–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. , Acin, P. R. , Geghman, K. D. , Manfredi, G. , Lu, B. , & Li, C. (2011). Pink1 regulates the oxidative phosphorylation machinery via mitochondrial fission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108, v12920–v12924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal, M. J. , & Cuervo, A. M. (2016). Regulation of liver metabolism by autophagy. Gastroenterology, 150, 328–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, J. C. , & Lilley, E. (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): New requirements for publication in BJP. British Journal of Pharmacology, 172, 3189–3193. 10.1111/bph.12955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, T. G. , & Muqit, M. M. (2017). PINK1 and Parkin: Emerging themes in mitochondrial homeostasis. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 45, 83–91. 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J. S. , Nakahira, K. , Chung, K. P. , DeNicola, G. M. , Koo, M. J. , Pabon, M. A. , … Choi, A. M. (2016). NOX4‐dependent fatty acid oxidation promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages. Nature Medicine, 22, 1002–1012. 10.1038/nm.4153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Murata, H. , Takamatsu, H. , Liu, S. , Kataoka, K. , Huh, N. H. , & Sakaguchi, M. (2015). NRF2 regulates PINK1 expression under oxidative stress conditions. PLoS ONE, 10, e0142438 10.1371/journal.pone.0142438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera, R. M. , Di, M. C. , & Ballabio, A. (2019). MiT/TFE family of transcription factors, lysosomes, and cancer. Annual Review of Cancer Biology, 3, 203–222. 10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030518-055835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robblee, M. M. , Kim, C. C. , Porter, A. J. , Valdearcos, M. , Sandlund, K. L. , Shenoy, M. K. , … Koliwad, S. K. (2016). Saturated fatty acids engage an IRE1α‐dependent pathway to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in myeloid cells. Cell Reports, 14, 2611–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomone, F. , Godos, J. , & Zelber, S. S. (2016). Natural antioxidants for non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: Molecular targets and clinical perspectives. Liver International, 36, 5–20. 10.1111/liv.12975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, R. J. , Drižytė, K. , Casey, C. A. , & McNiven, M. A. (2017). Hepatic lipophagy: New insights into autophagic catabolism of lipid droplets in the liver. Hepatology Communications, 1, 359–369. 10.1002/hep4.1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre, C. , De, C. R. , Mansueto, G. , Saha, P. K. , Vetrini, F. , Visvikis, O. , … Wollenberg, A. C. (2013). TFEB controls cellular lipid metabolism through a starvation‐induced autoregulatory loop. Nature Cell Biology, 15, 647–658. 10.1038/ncb2718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R. , Kaushik, S. , Wang, Y. , Xiang, Y. , Novak, I. , Komatsu, M. , … Czaja, M. J. (2009). Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature, 458, 1131–1135. 10.1038/nature07976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, S. , Hikita, H. , Tatsumi, T. , Sakamori, R. , Nozaki, Y. , Sakane, S. , … Tabata, K. (2016). Rubicon inhibits autophagy and accelerates hepatocyte apoptosis and lipid accumulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology, 64, 1994–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van, D. W. B. , Koek, G. H. , Bast, A. , & Haenen, G. R. (2017). The potential of flavonoids in the treatment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57, 834–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, X. , Xu, C. , Lin, Y. , Lu, C. , Li, D. , Sang, J. , … Yu, C. (2016). Uric acid regulates hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance through the NLRP3 inflammasome‐dependent mechanism. Journal of Hepatology, 64, 925–932. 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Liu, W. , Yao, L. , Zhang, X. , Zhang, X. , Ye, C. , … Ai, D. (2017). Hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acids and epoxyeicosatetraenoic acids attenuate early occurrence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174, 2358–2372. 10.1111/bph.13844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. , Liu, X. , Nie, J. , Zhang, J. , Kimball, S. R. , Zhang, H. , … Shi, Y. (2015). ALCAT1 controls mitochondrial etiology of fatty liver diseases, linking defective mitophagy to steatosis. Hepatology, 61, 486–496. 10.1002/hep.27420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. A. , Ni, H. M. , Ding, Y. , & Ding, W. X. (2015). Parkin regulates mitophagy and mitochondrial function to protect against alcohol‐induced liver injury and steatosis in mice. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 309, G324–G340. 10.1152/ajpgi.00108.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi, Z. M. , Koenig, A. B. , Abdelatif, D. , Fazel, Y. , Henry, L. , & Wymer, M. (2016). Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—Meta‐analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology, 64, 73–84. 10.1002/hep.28431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z. , Umemura, A. , Sanchez‐Lopez, E. , Liang, S. , Shalapour, S. , Wong, J. , … Karin, M. (2016). NF‐κB restricts inflammasome activation via elimination of damaged mitochondria. Cell, 164, 896–910. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R. , Yazdi, A. S. , Menu, P. , & Tschopp, J. (2011). A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature, 469, 221–225. 10.1038/nature09663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W. , Jia, Q. , Wang, Y. , Zhang, Y. , & Xia, M. (2012). The anthocyanin cyanidin‐3‐O‐β‐glucoside, a flavonoid, increases hepatic glutathione synthesis and protects hepatocytes against reactive oxygen species during hyperglycemia: Involvement of a cAMP‐PKA‐dependent signaling pathway. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 52, 314–327. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Chemical structure of C3G

Figure S2. The effects of C3G on cell viability and lipid accumulation. (A, B) Cell viability. AML‐12 and HepG2 cells were treated with 100 μM C3G for 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72 or 96 h. (C, D) Cell viability. AML‐12 and HepG2 cells were treated with 0, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 or 400 μM C3G for 12 h. (E, F) The TG content and representative images of Oil‐red O (original magnification 40×) staining in AML‐12 cells. AML‐12 cells were maintained in medium containing 2% BSA and treated with 400 μM palmitic acid for 12 h, then treated with or without 50 μM chloroquine for 4 h, followed by 12 h post‐treatment with or without 100 μM C3G for 12 h. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05

Figure S3. The effects of C3G on palmitic acid‐induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. AML‐12 cells were maintained in medium containing 2% BSA and treated with palmitic acid for 12 h, then treated with or without C3G for 12 h. (A) Content of IL‐1β in cell lysates and supernatant of AML‐12 cells. (B) Content of IL‐18 in cell lysates and supernatant of AML‐12 cells. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05

Figure S4. The effects of C3G on oxidative stress in AML‐12 cells. AML‐12 cells were maintained in medium containing 2% BSA and treated with palmitic acid for for 12 h, then treated with or without C3G for 12 h. (A, B) ROS content in AML‐12 cells. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05

Figure S5. Representative hepatic TEM images of healthy controls and patients with NAFLD. Autophagosomes (arrow). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05

Figure S6. Food intake and physical activity. (A) Food intake in different groups (n = 9 mice/group). (B‐D) Physical activity in different groups (n = 9 mice/group). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

Figure S7. C3G enhances autophagic flux in AML‐12 cells. (A) The mRNA expression of autophagy‐related genes in AML‐12 cells. AML‐12 cells were treated with 100 μM C3G for 12 h. (B) Protein abundance of p62 and LC3 in AML‐12 cells (n = 6). AML‐12 cells were treated with C3G for 12 h and then treated with or without chloroquine for 4 h. (C) Representative images of autophagosomes (yellow puncta) and autolysosomes (red puncta) (n = 6). AML‐12 cells were transfected with recombinant adenovirus mRFP‐GFP‐LC3 and then treated with C3G. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

Figure S8. Hepatic mRNA abundance of autophagy‐related genes. Mice were fed either a chow diet or a HFD for 16 weeks. C3G‐treated mice were fed a HFD for 12 weeks and then fed a HFD containing 0.2% C3G for another 4 weeks. (n = 9 mice/group). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

Table S1. The baseline characteristics of controls and NAFLD subjects. Values are mean ± SEM

Table S2. The primers sequences used for qRT‐PCR