Abstract

With dental services currently altered, dentists are being asked to provide advice, analgesia and antibiotics in situations where they would normally be offering operative care. Dentists are familiar with using analgesia for short courses for their patients, but using higher-dose regimes and for periods of over two weeks brings special challenges. This paper reviews the areas where special precautions are needed when using analgesia in the current situation.

Key points

Outlines the medical complications of prolonged high-dose analgesia use.

Gives dentists a framework for safely providing adequate analgesia to dental patients during the COVID-19 aerosol generating procedures restrictions.

Identifies the areas where dentists need to link with medical GPs for providing analgesia to dental patients.

Introduction

Both ibuprofen and diclofenac are safe medicines if used appropriately in healthy adult patients.1 In the current Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) COVID-19 recommendations for dental care,2 dentists are being advised to offer advice, analgesia and antibiotics (AAA) to patients, where indicated. Many patients will experience a delay in operative emergency treatment, resulting in longer courses and higher doses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) analgesic use than are familiar to dentists. Table 1 shows suggested analgesic regimes in primary care for moderate and severe dental pain in adults, but the aim is to prescribe and advise the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration needed. Dentists must be aware of the adverse effects and medical cautions in these circumstances in order to safely advise their patients and to know when it is appropriate to liaise with the patient's GP for provision of analgesia. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on the use of NSAIDs in patients with pre-existing medical conditions is available,3 and the British National Formulary (BNF) and the BNF App are available for guidance.

Table 1.

Analgesia for moderate and severe dental pain, adapted from SDCEP2

| Dental pain | Treatment |

|---|---|

| For moderate dental pain in adults, an appropriate five-day regimen is either: |

Paracetamol: 2 x 500 mg tablets up to four times daily (ie every four to six hours), or Ibuprofen: 2 x 200 mg tablets up to four times daily (ie every four to six hours), preferably after food |

| For severe dental pain in adults, an appropriate five-day regimen is either: |

Increase the dose of ibuprofen to 3 x 200 mg tablets up to four times daily, preferably after food, or Ibuprofen and paracetamol together without exceeding the standard daily dose or frequency for either drug, or Diclofenac (1 x 50 mg tablet three times daily) and paracetamol together without exceeding the recommended daily dose or frequency for either drug |

Analgesia in dental patients with COVID-19

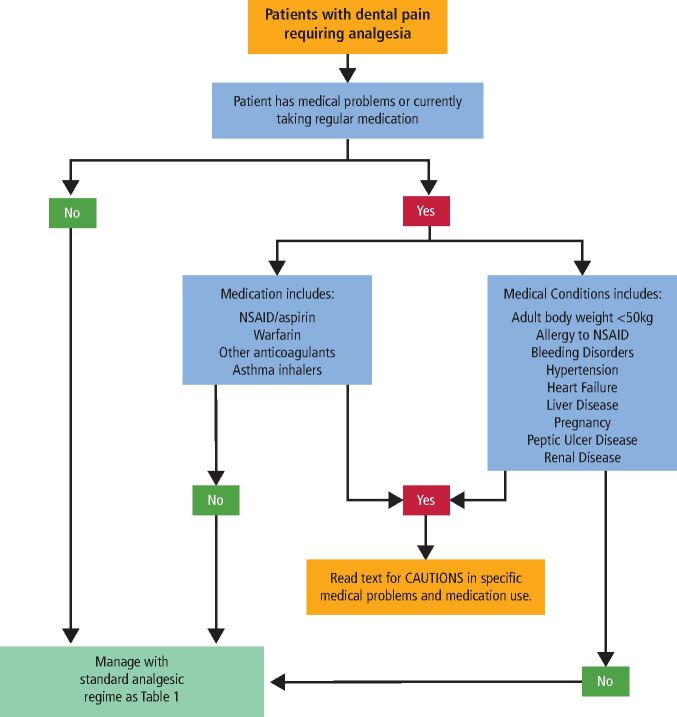

Currently there is no guidance in the literature suggesting that changes should be made to analgesia regimes for dental patients with COVID symptoms nor to support avoiding ibuprofen in this group, despite the large numbers infected since the virus was first reported. At present, the same analgesic plan should be used for both COVID-positive and negative primary care patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Analgesic plan for patients with dental pain

Paracetamol

Paracetamol is a safe analgesic taken up to the recommended doses and is the first analgesic that dentists should recommend. It is the best choice in patients with liver and kidney disease, although the dose may have to be reduced in severe liver disease.4

Dentists must be aware of the risk of accidental paracetamol overdose in persisting severe dental pain. This risk is higher in patients with a body weight under 50 kg and patients with pre-existing liver disease. Patients may not be aware of the paracetamol content of some over-the-counter analgesics and may combine them with generic paracetamol. Siddique et al.5 found that dental pain was the largest cause of accidental paracetamol overdose in a large case series. If more than 8 x 500 mg equivalent dose of paracetamol is found to have been taken by an adult in 24 hours, the patient should be referred immediately for medical assessment. The threshold is lower in children and will vary with the child's weight. The local paediatric emergency department will advise if the dentist is unsure whether the child is at risk.

Paracetamol with codeine

Paracetamol combined with codeine is an effective analgesic for moderate to severe dental pain6 and is available as co-codamol in two formulations - 8/500 and 15/500. The first number refers to the codeine dose in each tablet and the second refers to the paracetamol dose. Neither can be prescribed by a dentist, but the lower strength (8/500) is available to buy from pharmacies without prescription. If the higher strength (15/500) is needed, the dentist should liaise with the patient's GP. Solpadeine Max contains 12.8/500 codeine and paracetamol, and is available from pharmacies without prescription.

NSAIDs

In healthy individuals, NSAID medicines can be safe for treating moderate to severe dental pain such as ibuprofen in doses up to 2,400 mg/day. In all patient groups, the lowest effective dose for the shortest period practical should be given, but with certain medical conditions or risks, NSAIDs should only be used with caution or at a reduced dosage. The need to continue the use of NSAIDs should be reviewed at least every two weeks, and may require the advice of and monitoring from the patient's GP if the dentist has concern about extended treatment.

The guidance below is to help the dentist identify patients in whom higher-dose ibuprofen (600 mg three or four times daily) or diclofenac at any dose should be approached with caution. High doses of NSAIDs must be used with great caution in the elderly and the GP should be consulted if the dentist is in any doubt about the safety of using these medicines in a particular patient.

Patients with existing NSAID use including low-dose aspirin

Patients taking NSAID medicines for pre-existing conditions such as arthritis should not routinely be given ibuprofen or diclofenac as additional analgesia.3 If analgesia is required beyond maximum paracetamol dose, treatment needs to be in conjunction with the GP who can offer 30/500 co-codamol or another opioid. Patients taking low-dose daily aspirin (75 mg/day) for cardiovascular protection can be given NSAIDs if they have none of the other NSAID contraindications below,7 but only if another analgesic is not possible and the dose of ibuprofen should be restricted to 1,200 mg maximum.3 There is some evidence that ibuprofen in higher doses may reduce the antiplatelet benefit of low-dose aspirin and diclofenac may be preferred when severe dental pain is being treated.8

Oral anticoagulant medicines and patients with bleeding tendencies

Patients taking novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) medicines such as apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran and edoxaban can take NSAIDs as suggested for moderate and severe dental pain,9,10 but they will have enhanced post-extraction bleeding due to the NSAID's inhibiting platelet function. Standard post-extraction haemorrhage precautions will control this in most cases and the use of the NSAID must be reviewed after two weeks.

Warfarinised patients have a significant risk of drug interactions with all NSAIDs and they should not be used unless international normalised ratio (INR) monitoring is available to the patient.11 Be aware that INR monitoring services may be reduced currently. The availability of this for an individual patient should be discussed with the GP. However, where possible, an alternative analgesia regime should be given via the GP, such as 30/500 co-codamol or other opioid. Patients who have significant bleeding tendencies such as haemophilia should not be given NSAIDs without the prior approval from their haematologist.

Known allergy to NSAID, history of angioedema and chronic renal failure

NSAIDs should not be used in these patient groups and the dentist should contact the patient's GP to discuss alternative analgesic options. Renal failure can be made quickly worse by the use of NSAID medicines.12 Common groups to have renal failure include patients with diabetes mellitus (type 1 and 2) and patients with longstanding poor hypertension control. If in any doubt, the patient should have an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) blood test requested from the GP - a value of >60 is safe for NSAID use. Below this level, the GP should be asked for advice as to the best analgesia regime.

Asthma

Asthma can be exacerbated by NSAID medications;13 avoid diclofenac use in asthmatics.

Mild asthma (blue and brown inhalers only)

Patients with mild asthma are generally safe for short courses of ibuprofen of up to seven days in the doses recommended for moderate and severe pain. When advising patients to use ibuprofen beyond this, the patient must be given instructions to stop the ibuprofen and contact the prescriber immediately if their asthma control starts to deteriorate.

Moderate asthma (blue and any other colour of inhaler)

Patients with moderate asthma can be given NSAIDs in the regime for moderate dental pain (3 x 400 mg ibuprofen in 24 hours), but with instructions to stop the NSAID and contact the prescriber immediately if their asthma control starts to deteriorate.

Severe asthma

This includes patients who have had prednisolone use in last six months or any hospital admission for asthma. Do not use any NSAID drugs in these patients. Contact the patient's GP for an alternative analgesic regime.

Pregnancy

Paracetamol is the safest analgesic to prescribe during pregnancy, but prolonged or very high doses can be associated with subsequent childhood asthma, particularly if taken in the second trimester. However, doses of up to 4 g daily remain to have any adverse effects proven.3 Dentists should avoid prescribing NSAID medicines in pregnancy without first consulting the patient's GP. Alternative regimes available through the GP include 30/500 co-codamol or other opioid. The GP may still recommend using an NSAID regime such as that outlined for moderate dental pain, as NSAIDs are not absolutely contraindicated until 30 weeks' gestation and beyond.14 Patients who are breastfeeding can be given NSAIDs, but the higher doses should only be used in exceptional circumstances and after discussion with the GP. Paracetamol is preferred.

Patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease

Most of these patients will be taking a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and this will protect from the gastric irritation associated with NSAIDs. In these cases, the dentist can use the NSAID regimes recommended for moderate and severe pain, but if the treatment course for severe dental pain is prolonged beyond two weeks, then the dentist should liaise with the GP to ensure no other gastric precautions are needed.

If a patient is not taking a PPI and has a history of at least one episode of proven peptic ulcer disease (usually by previous endoscopy), has another risk factor for gastric bleeding such as an anticoagulant and is likely to be taking the NSAID for more than two weeks, the dentist should discuss the need for a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) with the GP before prescribing, especially if the patient is already taking aspirin.15 Box 1 gives risk groups for GI bleeding; patients should be considered high risk if they have a history of previous ulcer disease or more than two risk factors and at moderate risk if they have one or two risk factors.3

Patients with treated and uncontrolled hypertension

Long-term use of NSAIDS may increase blood pressure and the impact of this effect varies from person to person.16 For treatments of up to two weeks in a patient with properly treated hypertension and no renal disease, the recommendations for the use of NSAIDs in moderate and severe dental pain apply. If treatment is to continue after two weeks, the dentist should discuss management with the GP and the NSAID should continue as long as blood pressure monitoring and renal function monitoring is carried out regularly. The combination of NSAIDs, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and diuretics can significantly increase the risk of kidney damage in some patients.3 If blood pressure starts to rise or renal function deteriorates, an alternative analgesic regime should be considered.

Patients with uncontrolled hypertension (>140/90) should not be prescribed high-dose ibuprofen (2,400 mg/day) or diclofenac without consulting the patient's GP.3

Patients with cardiac risk, significant cardiac failure with leg oedema, left ventricular dysfunction or peripheral oedema for any other reason

These patients may deteriorate or have an acute cardiac event with moderate-to-high-dose NSAID use,17 and the risk depends upon the potency of the drug, the dose given and the duration of treatment. Ibuprofen should be restricted to a maximum of 1,200 mg daily and diclofenac should be avoided.3 If there is a likelihood of the treatment extending beyond two weeks, then the patient's GP should be consulted about the benefit of using an alternative analgesic regime such as co-codamol 30/500 or another opioid.

Box 1 Risk factors for NSAID-induced gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events, adapted from NICE3.

Aged over 65 years

A high dose of NSAID (2,400 mg/day)

A history of gastroduodenal ulcer, GI bleeding or gastroduodenal perforation

Concomitant use of medications that are known to increase the likelihood of upper GI adverse events (for example, anticoagulants, corticosteroids, selective 5-hydroxytryptamine reuptake inhibitors)

A serious comorbidity, such as cardiovascular disease, hepatic or renal impairment (including dehydration), diabetes or hypertension

Heavy smoking

Excessive alcohol consumption

Previous adverse reaction to NSAIDs

Prolonged requirement for NSAIDs.

Use of prolonged analgesia in children

Analgesia for children is an important part of paediatric dentistry.18 Dentists can prescribe paracetamol and ibuprofen for use in children and the standard doses for each age group are given in Table 2. Aspirin and diclofenac should not be used. Children should not be given prolonged courses of analgesia using this regime beyond two weeks without reassessing the possibility of early definitive dental care or discussion with the GP.

Table 2.

Analgesia for children, adapted from SDCEP2

| Dental pain | Treatment | Dose for each age group |

|---|---|---|

| For dental pain in children, an appropriate five-day regimen is either: | Paracetamol (500 mg tablets, or 120 mg/5 ml or 250 mg/5 ml oral suspension), dose depending on age, up to four times daily (max = four doses in 24 hours) |

6-12 months = 120 mg 2-3 years = 180 mg 4-5 years = 240 mg 6-7 years = 240-250 mg 8-9 years = 360-375 mg 10-11 years = 480-500 mg 12-15 years = 480-750 mg 16-17 years = 500 mg-1 g |

| Ibuprofen (200 mg tablets, or 100 mg/5 ml oral suspension), dose depending on age, preferably after food up to three times daily unless indicated otherwise |

6-11 months = 50 mg (four times daily) 1-3 years = 100 mg 4-6 years = 150 mg 7-9 years = 200 mg 10-11 years = 300 mg 12-17 years = 300-400 mg |

The medical conditions mentioned above will all occur in children; asthma, allergies and diabetes mellitus are the most frequently seen and the cautions above will apply.

It is best with children to use a single analgesic - either paracetamol or ibuprofen, whichever works best for the individual child. An alternative regime is alternating paracetamol and ibuprofen at each dose. Combining paracetamol and ibuprofen is permitted in the same manner as in adults, using the age-specific paediatric dosages, but this runs the risk of confusion about the total dose of each drug given and the possibility of accidental overdose. Remember that the margin between safe and toxic drug doses is much lower in children.

A dentist should not start a PPI in a child, and if the dentist has concerns about the need for a PPI, then the GP must be consulted.

Summary

Dentists will be asked to provide high dosages of analgesics in the current COVID-19 situation. This will often involve using familiar drugs but in higher doses and for more prolonged periods. The dentist must be clear about the medical consequences of these prescribing changes, and the consequences and options in special medical groups, and must ensure to use the lowest effective dose for the shortest period possible. It is important that the analgesia regime is tailored to the patient's medical circumstances and, where appropriate, discussed with the patient's GP.

References

- 1.Moore P A, Ziegler K M, Lipman R D, Aminoshariae A, Carrasco-Labra A, Mariotti A. Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental pain: An overview of systematic reviews. J Am Dent Assoc 2018; 149: 256-265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.SDCEP. Management of Acute Dental Problems During COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available at http://www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/acutedentalproblemscovid19/ (accessed April 2020).

- 3.NICE. NSAIDS - prescribing issues. 2019. Available at https://cks.nice.org.uk/nsaids-prescribing-issues#!scenario (accessed April 2020).

- 4.Dwyer J P, Jayasekera C, Nicoll A. Analgesia for the cirrhotic patient: a literature review and recommendations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 29: 1356-1360. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Siddique I, Mahmood H, Mohammed-Ali R. Paracetamol overdose secondary to dental pain: a case series. Br Dent J 2015; DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.706. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gatoulis S C, Voelker M, Fisher M. Assessment of the efficacy and safety profiles of aspirin and acetaminophen with codeine: results from 2 randomized, controlled trials in individuals with tension-type headache and postoperative dental pain. Clin Ther 2012; 34: 138-148. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gurbel P, Tantry U, Weisman S. A narrative review of the cardiovascular risks associated with concomitant aspirin and NSAID use. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2019; 47: 16-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Schuijt M P, Huntjens-Fleuren H W H A, de Metz M, Vollaard E J. The interaction of ibuprofen and diclofenac with aspirin in healthy volunteers. Br J Pharmacol 2009; 157: 931-934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Friedman R J, Kurth A, Clemens A, Noack H, Eriksson B I, Caprini J A. Dabigatran etexilate and concomitant use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or acetylsalicylic acid in patients undergoing total hip and total knee arthroplasty: no increased risk of bleeding. Thromb Haemost 2012; 108: 183-190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.NICE. 1.4 Assessment of stroke and bleeding risks. 2014. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180/chapter/1-Recommendations#assessment-of-stroke-and-bleeding-risks-2 (accessed April 2020).

- 11.SDCEP. Management of Dental Patients Taking Anticoagulants or Antiplatelet Drugs: Dental Clinical Guidance. 2015. Available at https://www.sdcep.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/SDCEP-Anticoagulants-Guidance.pdf (accessed April 2020).

- 12.NICE. 1.4 Identifying the cause(s) of acute kidney injury. 2019. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng148/chapter/Recommendations#identifying-the-causes-of-acute-kidney-injury (accessed April 2020).

- 13.Specialist Pharmacy Service. NSAID safety audit 2018-19. 2018. Available at https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/cannonsteroidalantiinflammatorydrugsbeusedinadultpatientswith-asthma/ (accessed April 2020).

- 14.Black E, Khor K E, Kennedy D et al. Medication Use and Pain Management in Pregnancy: A Critical Review. Pain Pract 2019; 19: 875-899. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Goldstein J L, Huang B, Amer F, Christopoulos N G. Ulcer recurrence in high-risk patients receiving nonsteroidalanti-inflammatory drugs plus low-dose aspirin: results of a post HOC subanalysis. Clin Ther 2004; 26: 1637-1643. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hwang A Y, Dave C V, Smith S M. Use of Prescription Medications That Potentially Interfere With Blood Pressure Control in New-Onset Hypertension and Treatment-Resistant Hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2018; 31: 1324-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Arfè A, Scotti L, Varas-Lorenzo C et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of heart failure in four European countries: nested case-control study. BMJ 2016; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.i4857. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.AAPD. Pain Management in Infants, Children, Adolescents and Individuals with Special Health Care Needs. 2018. Available at https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_Pain.pdf (accessed April 2020). [PubMed]