Abstract

The functional diversity of primary afferent neurons of the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) generates a variety of qualitatively and quantitatively distinct somatosensory experiences, from shooting pain to pleasant touch. In recent years, the identification of dozens of genetic markers specifically expressed by subpopulations of DRG neurons has dramatically improved our understanding of this diversity and provided the tools to manipulate their activity and uncover their molecular identity and function. Opioid receptors have long been known to be expressed by discrete populations of DRG neurons, in which they regulate cell excitability and neurotransmitter release. We review recent insights into the identity of the DRG neurons that express the delta opioid receptor (DOR) and the ion channel mechanisms that DOR engages in these cells to regulate sensory input. We highlight recent findings derived from DORGFP reporter mice and from in situ hybridization and RNA sequencing studies in wild-type mice that revealed DOR presence in cutaneous mechanosensory afferents eliciting touch and implicated in tactile allodynia. Mechanistically, we describe how DOR modulates opening of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) to control glutamatergic neurotransmission between somatosensory neurons and postsynaptic neurons in the spinal cord dorsal horn. We additionally discuss other potential signaling mechanisms, including those involving potassium channels, which DOR may engage to fine tune somatosensation. We conclude by discussing how this knowledge may explain the analgesic properties of DOR agonists against mechanical pain and uncovers an unanticipated specialized function for DOR in cutaneous mechanosensation.

Keywords: Delta opioid receptor, Excitability, Ion channels, Mechanosensation, Neuroanatomy, Neurotransmitter release, Pain, Primary afferent dorsal root ganglion neurons, Touch

1. Introduction: Diversity of Primary Afferent Somatosensory Neurons

Primary afferent somatosensory neurons detect and transmit information eliciting perception of temperature, touch, itch, pain, and positioning of body parts. Primary afferent somatosensory neurons are pseudounipolar neurons; their peripheral axons innervate organs in the periphery (e.g., skin, viscera, muscles, bones), and their central axons project onto neurons of the spinal cord dorsal horn and, in rare cases, brainstem dorsal column nuclei. Their somata are collected in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG, cervical to sacral segmental levels) and trigeminal ganglia (TG, head). Primary afferent somatosensory neurons shape the perception of our external and internal environments and are essential for our survival. The diversity of somatosensory stimuli translates into the outstanding functional and molecular diversity of primary afferent neurons. While primary afferent sensory neurons were categorized based on the size of their cell bodies (small, medium, large), myelination (unmyelinated, thinly, thickly myelinated), conduction velocity (slow C, fast Aδ, and Aβ fibers), activation threshold (low [touch] and high [pain]), and sensitivity (mechanical, thermal, chemical), genetic engineering techniques in mice have revealed in recent years dozens of classes, with specific molecular identities and contributions to somatosensation (Abraira and Ginty 2013; Delmas et al. 2011; Basbaum et al. 2009; Lumpkin and Bautista 2005; Lewin and Moshourab 2004; Le Pichon and Chesler 2014).

These studies have transformed our understanding of somatosensation by identifying genetic markers to label and manipulate discrete neural populations. For example, small to medium DRG neurons were considered to encode pain and medium to large neurons to encode touch or proprioception. We now know that small unmyelinated neurons include mechanosensory neurons that express TH, VGLUT3, and TAFA4 and are essential to touch (Delfini et al. 2013; Li et al. 2011; Seal et al. 2009), and pruritoreceptors that express MrgA3 and are essential to itch (Liu et al. 2009), but not to pain. Similarly, it is clear today that large myelinated neurons are not limited to mechanosensory neurons encoding touch, but include multiple classes of nociceptors (Woodbury et al. 2008; Luo et al. 2007; Ghitani et al. 2017; Arcourt et al. 2017). This has important practical implications for experimental design and data interpretation. First, labeling or recording DRG/TG neurons does not mean that pain is studied; the results are just as likely to be relevant to itch, touch, or proprioception. Second, studying unidentified neurons means pooling data from neurons that are almost certainly functionally heterogeneous, even if their cell bodies have similar sizes. This is also exemplified by the TRP channels TRPV1 and TRPM8, which are markers expressed by two populations of small-diameter neurons that specifically respond to noxious heat and capsaicin versus cool and menthol, respectively (Basbaum et al. 2009; Peier et al. 2002).

Opioid receptors, including DOR, have long been known to be expressed in DRG and TG across species (Fields et al. 1980; Buzas and Cox 1997; Zhu et al. 1998). Since our understanding of the functional organization of primary afferent somatosensory neurons is far more advanced for mouse DRG neurons, we describe in this chapter newly acquired knowledge regarding the identity of DOR-expressing DRG neurons in rodents and DOR function in these cells.

2. DOR Distribution in Dorsal Root Ganglia

It is accepted within the field that several classes of DRG neurons express DOR; however, the precise identity of these neurons is disputed (see 2.3.). Because the expression pattern of a gene within DRG neuron subtypes defines its contribution to somatosensation, resolving the identity of DOR-expressing neurons is of critical importance to defining the therapeutic potential of peripheral DOR analgesics (see Conclusion). We first focus on novel knowledge gained from the use of recently identified genetic markers for subpopulations of cutaneous mechanosensitive neurons in DORGFP mice. We next discuss these results in the context of the pre-existing literature on DOR distribution in DRG.

2.1. DOR-Expressing DRG Neurons Are Predominantly A LTMRs

The characteristic feature of DOR distribution in DRG, compared to that of the mu opioid receptor (MOR), is DOR enrichment in neurons with large-diameter cell bodies and myelinated axons (Fig. 1). DRG neurons with myelinated axons express neurofilament 200 (NF200) and are born earlier than unmyelinated nociceptors during embryonic development (Abraira and Ginty 2013; Liu and Ma 2011; Lallemend and Ernfors 2012). In situ hybridization studies in rodents established the presence and dense labeling of Oprd1 mRNA in DRG early during development in large and NF200-immunoreactive DRG neurons (Zhu et al. 1998; Mennicken et al. 2003; Bardoni et al. 2014).

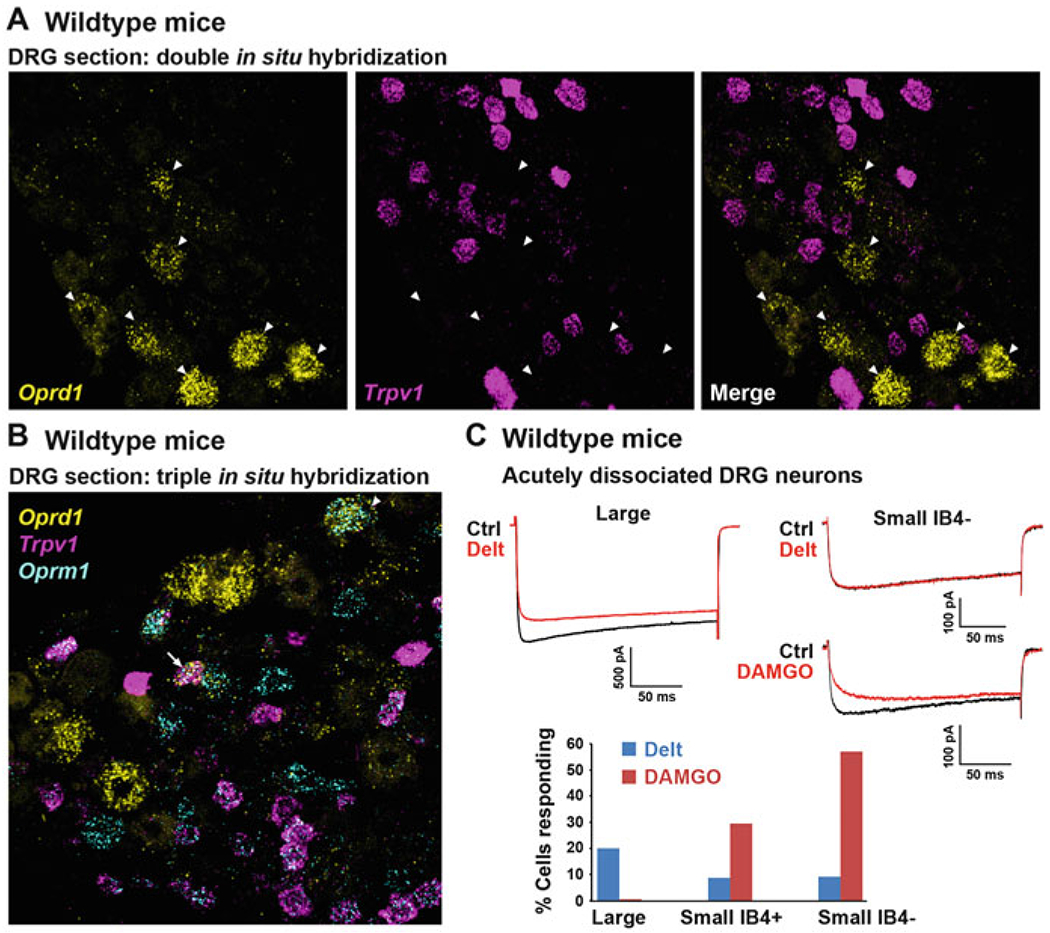

Fig. 1.

DOR is predominantly expressed by large-diameter DRG neurons, not by TRPV1+ and MOR+ small-diameter C nociceptors. (a) Single mRNA molecule labeling in DRG sections from wild-type mice reveals that DOR (Oprd1 gene) and TRPV1 are expressed by different populations of DRG neurons. Arrowheads indicate DOR+ neurons. (b) The great majority of TRPV1+ peptidergic C nociceptors co-express MOR (Oprm1 gene). MOR is also found in other DRG neuron types, including large-diameter neurons in which it occasionally co-occurs with DOR (arrowhead). The arrow shows a rare example of a C nociceptor co-expressing MOR, TRPV1, and DOR. (c) Consistent with histological data, electrophysiological recordings show that the DOR agonist deltorphin II (Delt), in contrast to the MOR agonist DAMGO, predominantly inhibits calcium currents in large-diameter DRG neurons from wild-type mice (modified from Bardoni et al. 2014). Images in a and b were provided by Dong Wang, Scherrer laboratory

More recently, the development of tools including DORGFP knockin mice (Scherrer et al. 2006) and RNA sequencing (Usoskin et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2009; Kolodziejczyk et al. 2015) has enabled the identification and categorization of DOR-expressing (DOR+) large-diameter NF200+ DRG neurons. Co-immunolabeling studies using DORGFP reporter mice revealed that the majority of DORGFP+ NF200+ neurons express the neurotrophin receptors Ret and/or TrkC (~60%, (Bardoni et al. 2014)), which identify several classes of low-threshold mechanosensitive A fibers (A low-threshold mechanoreceptors, A LTMRs).

Among these, DORGFP is predominantly expressed by Ret+ TrkC+ A LTMRs that innervate hair. These neurons project to the skin where their DORGFP+ axons arborize densely and form circumferential endings around numerous hair follicles (Fig. 2a, c). A recent study uncovered the anatomical and physiological properties of this class of A LTMRs also known as Aβ Field receptors (Bai et al. 2015), showing that they are activated by light stroking of the skin and skin indentation (including in the noxious range). Note also that Aβ Field receptor afferents are among the largest cells in mammals. Their central axons not only synapse in the spinal cord dorsal horn but also extend collaterals that ascend the dorsal columns and terminate in the gracile and cuneate nuclei in the brainstem (Bai et al. 2015). At the lumbar level, their peripheral axon can innervate the distal aspects of the limbs. Injection of the B fragment of cholera toxin (CTB), a retrograde tracer, in the brainstem dorsal column nuclei of DORGFP mice results in the backlabeling of numerous DORGFP+ DRG neurons, confirming DOR expression in this class of DRG neuron (Bardoni et al. 2014).

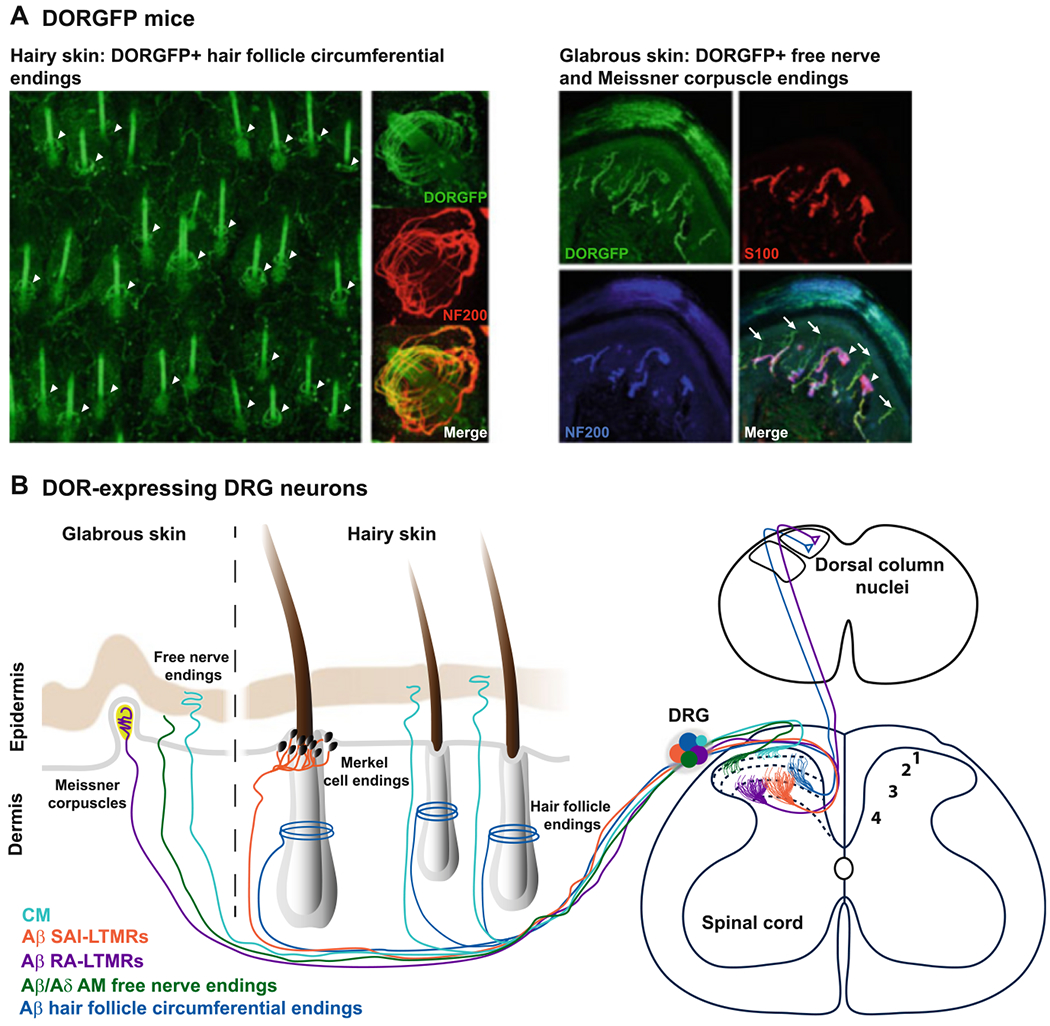

Fig. 2.

DOR is expressed by several classes of cutaneous mechanosensitive neurons. (a) DORGFP mice reveal DOR expression at the peripheral terminals of A low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs) forming circumferential endings around hair follicles (arrowheads in left panel). DOR is also expressed by DRG neurons innervating the glabrous skin, particularly by C nonpeptidergic nociceptors that co-express MrgprD and end as free nerve endings in the stratum granulosum (arrows in right panel) and by A LTMRs forming Meissner corpuscles (arrowheads in right panel). Modified from Bardoni et al. (2014). (b) Schematic summarizing the peripheral and central projection patterns of DOR+ cutaneous DRG neurons. CM C mechanonociceptors, SA slowly adapting, RA rapidly adapting

Other classes of A LTMRs that frequently express DORGFP (Bardoni et al. 2014) are Merkel cell afferents (Lumpkin and Bautista 2005) and Meissner corpuscle afferents (Pare et al. 2001). Merkel cell afferents are Aβ LTMRs that express TrkC (Bai et al. 2015), respond to skin indentation, and adapt slowly to mechanical stimulation (SA class of A LTMRs), while Meissner corpuscle afferents are rapidly adapting (RA) Ret+ Aβ LTMRs (Luo et al. 2009) and are low frequency vibration detectors (Fig. 3).

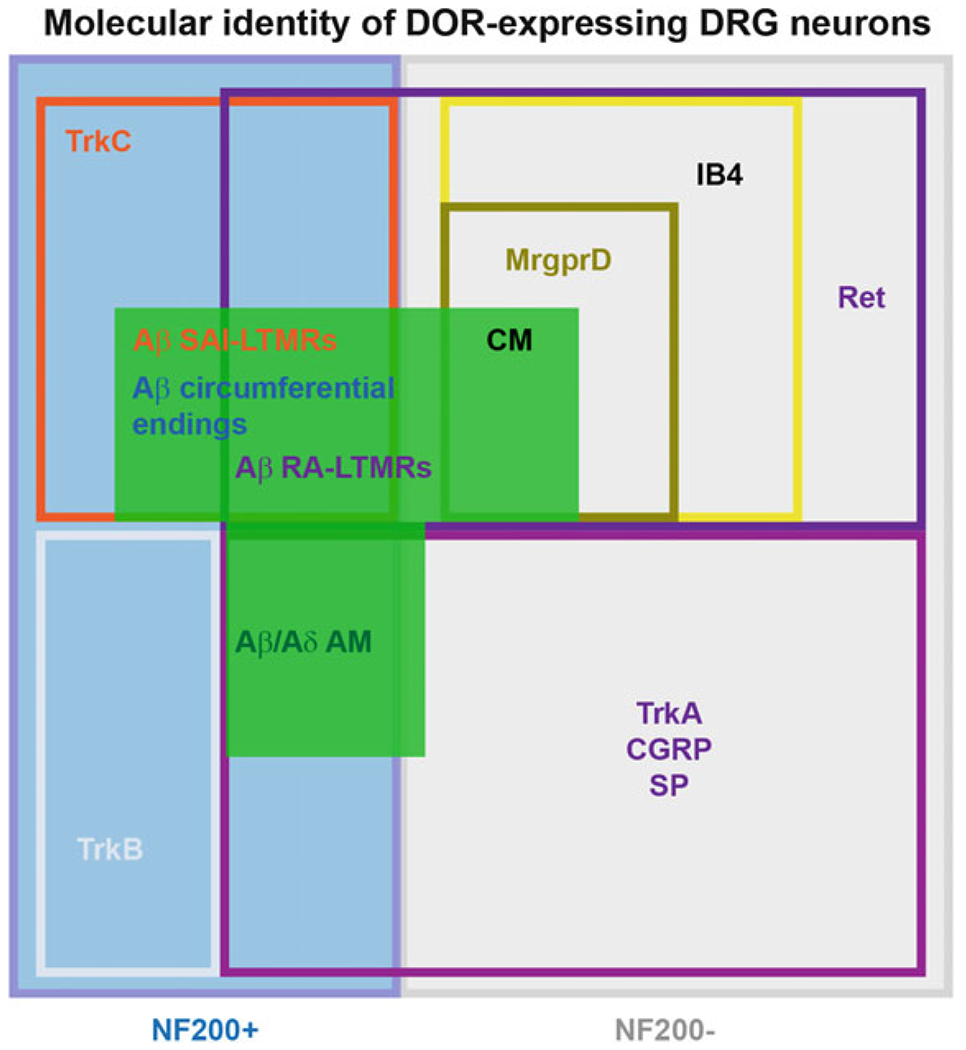

Fig. 3.

Functional and genetic diversity of A LTMRs and nociceptors expressing DOR. Multiple classes of molecularly heterogeneous DRG neurons express DOR. These different populations include myelinated nociceptors that express TrkA, as well as A LTMRs expressing other neurotrophin receptors such as Ret and TrkC. Ret is also expressed by the C nociceptors that express DOR, which correspond to a subpopulation of IB4-binding MrgprD+ mechanosensitive afferents

Importantly, DOR is not restricted to A LTMRs, but is also expressed by high-threshold mechanosensitive A fibers (i.e., A HTMRs, myelinated nociceptors), most of which can be identified by co-expression of NF200 and the nociceptor markers CGRP or TrkA (the receptor for NGF). Thus, approximately 36% of DORGFP+ NF200+ DRG neurons co-express TrkA and CGRP. Interestingly, this population of DRG neurons frequently co-expresses DOR and MOR (Bardoni et al. 2014; Joseph and Levine 2010), as MOR is expressed by virtually all C and A peptidergic nociceptors. NF200+ TrkA/CGRP+ neurons include cutaneous Aδ mechanonociceptors forming epidermal free nerve endings (Lawson et al. 2008), but also myelinated nociceptors innervating other tissues such as muscle afferents (Jankowski et al. 2013; Alvarez et al. 1992). Thus far the molecular identity of DOR+ myelinated DRG neurons suggests that proprioceptors, which innervate muscle spindles and tendons and encode positioning of body parts in space, do not express DOR (Bardoni et al. 2014) as they lack co-expression of parvalbumin and Runx3 (de Nooij et al. 2013).

This characterization of DOR+ DRG neurons in DORGFP reporter mice was recently confirmed in wild-type mice by an unbiased large-scale single-cell RNA sequencing study (Usoskin et al. 2015) and functional assays in spinal cord slices or acutely dissociated DRG neurons (Bardoni et al. 2014). Note that the single-cell RNA sequencing dataset from Usoskin et al. (2015) is publicly available at http://linnarssonlab.org/drg/. This webpage from the Linnarsson laboratory website contains a search engine that displays a scatter plot of expression in DRG neuron subpopulations for any gene of interest. Thus, searches for Oprd1, Oprm1, and Trpv1 genes show that Oprm1 and Trpv1 transcripts are enriched in neurofilament-negative DRG neurons that express peptides such as CGRP and substance P (i.e., unmyelinated peptidergic nociceptors), while Oprd1 transcripts are found in neurofilament-positive mechanosensory DRG neurons, consistent with neuroanatomical and electrophysiological studies in DORGFP and wild-type mice.

2.2. DOR-Expressing Unmyelinated Nociceptors Are MrgprD+ Nonpeptidergic Cutaneous Mechanonociceptors

Although at the thoracic level virtually all DORGFP+ DRG neurons are large and NF200+ (unpublished observation), in lumbar DRGs a significant proportion of DORGFP+ neurons are unmyelinated C fibers (~40% small-diameter cell bodies, NF200-negative) (Bardoni et al. 2014; Scherrer et al. 2009). These DORGFP+ C fibers do not express TH and thus are not C LTMRs (Bardoni et al. 2014), but C nociceptors. In situ hybridization studies in rats and wild-type mice established that the great majority of DOR+ C nociceptors do not express neuropeptides (substance P, CGRP) or TRPV1 and thus mostly belong to the nonpeptidergic class of C nociceptors (Mennicken et al. 2003; Bardoni et al. 2014; Minami et al. 1995). This expression pattern contrasts with that of MOR, which is highly expressed by TRPV1+ peptidergic C nociceptors (Scherrer et al. 2009; Minami et al. 1995) (Fig. 1b). In agreement with this segregated expression of DOR and MOR in C nociceptors, a transcriptomic analysis in rats indicated that ablation of TRPV1+ nociceptors profoundly reduced MOR expression in DRG but had little impact on DOR expression (Goswami et al. 2014).

DORGFP+ NF200-negative small-diameter neurons express Ret and bind the lectin IB4, a feature of nonpeptidergic C nociceptors in mouse. Thus, Ret is essential for the normal expression of DOR in the DRG (Franck et al. 2011) and DOR agonists inhibit GDNF-induced hyperalgesia (Joseph and Levine 2010). Furthermore, ablation studies in DORGFP mice revealed that DOR is expressed by the MAS-related GPR family member D (MrgprD) + subset of Ret + IB4+ nonpeptidergic C nociceptors. Administration of diphtheria toxin to DORGFP mice crossed with mutant mice that express the diphtheria receptor only in MrdprD+ neurons resulted in an almost complete loss of DOR+ small-diameter DRG neurons (Bardoni et al. 2014). MrdprD+ DRG neurons are cutaneous C nociceptors that respond to punctate mechanical stimuli and are critical to acute mechanical pain (Zylka et al. 2005; Dussor et al. 2008; Cavanaugh et al. 2009; Rau et al. 2009). Consistent with a function in cutaneous mechanonociception, DORGFP+ MrgprD+ nociceptors densely innervate the glabrous skin, forming epidermal free nerve endings that reach the stratum granulosum (Fig. 2b), in contrast to peptidergic nociceptors that terminate less superficially. Studies of visceral innervation thus far indicate that in contrast to TRPV1+ MOR+ peptidergic C nociceptors, which densely innervate viscera (Cavanaugh et al. 2011; De Schepper et al. 2008; Jones et al. 2005), DORGFP+ afferent terminals are very rare in visceral tissue (Scherrer et al. 2009).

2.3. Controversy Regarding DOR Distribution in DRG Neurons: Historical Considerations

The controversy regarding the expression pattern of DOR in DRG stems from three major sources. First, there is disagreement regarding which methods most accurately identify DOR-expressing neurons (antibodies, in situ hybridization, radioligand binding, RNA sequencing, DORGFP reporter mouse). Second, there are significant differences in the functional organization of DRG neurons in mice and rats. Third, there is disagreement regarding the interpretation of functional studies that used intrathecal opioid ligands or knockout mice to probe DOR function in pain at the DRG/spinal level. We focus our discussion below on the first point.

Following cloning of the Oprd1 gene in 1992 (Kieffer et al. 1992; Evans et al. 1992) and the determination of the DOR amino acid sequence, anti-DOR antibodies could be generated. Immunohistochemistry became the method of choice to investigate DOR distribution in tissues. In 1993, Dado, Elde, and colleagues reported the production of a rabbit antiserum generated by injection of a synthetic peptide consisting of the amino acids 3–17 of the DOR sequence (i.e., amino-terminal, extracellular). During the following decade, the immunoreactivity generated by this antibody (Ab3–17-ir) was used extensively to analyze DOR distribution in DRG and its subcellular localization in primary afferent neurons (Dado et al. 1993; Zhang et al. 1998; Riedl et al. 2009; Overland et al. 2009; Bao et al. 2003; Guan et al. 2005). Early studies reported that Ab3–17-ir was mostly associated with small-diameter DRG neurons co-expressing substance P and CGRP (Dado et al. 1993; Zhang et al. 1998). These reports strongly influenced research directions in the following decade and led to the idea that DOR would be predominantly expressed by peptidergic C nociceptors. Ab3–17 was also used in studies that proposed that DOR agonists can promote the insertion of DOR into the DRG neuron plasma membrane, via a direct substance P-DOR interaction in large dense-core vesicles [(Bao et al. 2003; Guan et al. 2005), reviewed by (Gendron et al. 2015)]. At the time, Oprd1 knockout mice were not available (Filliol et al. 2000; Zhu et al. 1999), and the pre-adsorption test was instead used to test Ab3–17-ir specificity. Preincubation of the Ab3–17 with the 3–17 synthetic peptide eliminated Ab3–17-ir, confirming the high affinity of the synthetic peptide for the antibody. It is clear, however, that the pre-adsorption test does not demonstrate that the immunoreactivity pattern generated by Ab3–17 in tissues results from recognition of DOR (Holmseth et al. 2012).

An important misconception is that the controversy originates from observations made using the DORGFP reporter mouse. This view is factually incorrect: it was apparent that Ab3–17-ir pattern in DRG and spinal cord did not match DOR distribution defined with other techniques, well before the generation of DORGFP mice in 2006. In 1995, Minami et al. using double in situ hybridization studies established that mRNAs encoding DOR and substance P were localized in distinct DRG neurons (Minami et al. 1995), consistent with Mennicken et al. later observation that Oprd1 mRNA was preferentially found in NF200+ and large-diameter DRG neurons (Mennicken et al. 2003). Ab3–17-ir pattern in the CNS also did not match the known distribution of Oprd1 mRNA or the binding pattern of DOR radioligands (Arvidsson et al. 1995; Mansour et al. 1987; Kitchen et al. 1997). In the spinal cord, Ab3–17-ir was restricted to the terminals of peptidergic DRG neurons in the superficial dorsal horn, while Oprd1 mRNA (Mennicken et al. 2003; Cahill et al. 2001) and DOR radioligand binding (Mennicken et al. 2003) are present throughout the dorsal and ventral horns, consistent with electrophysiological recordings documenting the existence of DOR-expressing spinal neurons (Eckert and Light 2002). Note also that numerous other anti-DOR antibodies were produced and generated different i.r. patterns compared to Ab3–17-ir. Some of these antibodies may have recognized DOR based on the observation that their i.r. pattern resembled DOR radioligand binding pattern (e.g., see Cahill et al. 2001). In the absence of specificity control in knockout mice for each serum and lot used, antibody specificity remains difficult to estimate.

The generation of DORGFP mice drew attention to and revived the pre-existing controversy, because the DORGFP expression pattern does not match the Ab3–17-ir pattern, but is consistent with Oprd1 mRNA distribution or DOR radioligand binding pattern in wild-type mice throughout the nervous system (Bardoni et al. 2014; Scherrer et al. 2006; Scherrer et al. 2009). DOR KO mice allowed examination of these inconsistencies in the 2000s and showed that binding of radioligand was lost in knockout mice (Bardoni et al. 2014; Scherrer et al. 2009; Goody et al. 2002), validating the specificity of this approach. By contrast, Ab3–17-ir was intact in DOR knockout mice (Scherrer et al. 2009), indicating that this antibody recognizes a molecule other than DOR. Other studies reported decreased Ab3–17-ir in DOR knockout mice (Overland et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2010), a puzzling result given the absence of Oprd1 mRNA and DOR binding sites in the great majority of Ab3–17-immunoreactive neurons and regions in the nervous system in wild-type mice.

As mentioned initially, species differences have also contributed to the controversy regrading DOR expression pattern (and co-expression with MOR) in DRG. TRPV1+ CGRP+ DRG neurons and IB4-binding nonpeptidergic nociceptors are almost completely nonoverlapping populations in mice, but substantially overlap in rats (Price and Flores 2007). Regarding functional assays, intrathecal injections of DOR ligands may also activate receptors expressed by spinal neurons, or present on brainstem descending axons, preventing definitive conclusions about DOR in DRG neurons. Virtually all DOR agonists can to some extent bind and activate MOR, particularly at high doses and given broader MOR expression in DRG neurons. Often, naltrindole is used to provide evidence of DOR involvement; however, naltrindole can also block MOR-mediated responses. For example, naltrindole co-injection can block the increase in latency for tail withdrawal caused by intrathecal DAMGO (unpublished observation). Data on DOR expression and function in cultured DRG neurons can also be difficult to interpret. DRG somatosensory neurons are tuned to respond to their extracellular environment and injuries. Axotomy (i.e., occurring during dissection) and the composition of the culture medium (e.g., serum, growth factors, neurotrophins such as NGF) profoundly alter gene expression (e.g., ion channels and GPCRs defining excitability and responsiveness) and transform DRG neuron molecular identity. To our knowledge, no study has rigorously characterized how the culturing process and the factors present in the medium impact each class of DRG neuron, including opioid receptor expression and signaling, compared to the in vivo physiologic condition. While cultured DRG neurons can be very useful to study molecular mechanisms such as gating of ion channels (i.e., TRPV1 gating by capsaicin) or ligand binding to GPCRs, whether they properly model physiological receptor expression and function in DRG neurons in vivo is uncertain. To address this aim, it may be preferable to use acutely dissociated DRG neurons within hours of dissection. It is clear that all methods used to study DOR distribution have limitations, including DORGFP mice. While the knockin approach is likely to faithfully report Oprd1 promoter activity and identify DOR-expressing cells, the insertion/addition of the GFP sequence/tag may modify certain aspects of mRNA processing and protein function. The use of multiple approaches will likely be necessary to address this controversy. Specifically, the emergence of novel techniques for quantifying gene expression with unprecedented sensitivity in wild-type mouse or rat DRG, by RNA sequencing and combinatorial detection of single mRNA molecules for multiple genes (Fig. 1a, b), will be particularly useful, given that protein function in a cell implies mRNA presence in its cell body.

3. Molecular and Physiological Consequences of DOR Activation in DRG Neurons

Very few studies have investigated DOR signaling in DRG neurons in vivo or in acutely dissociated DRG neurons that endogenously express DOR, such as A LTMRs. We review these studies here, along with those using cultured DRG neurons and DRG neurons transfected to express DOR. We focus on ion channel mechanisms relevant for DOR control of DRG neuron excitability and neurotransmitter release (Fig. 4). We recommend other excellent review articles and book chapters describing general mechanisms of DOR signaling via G protein and adenylate cyclase or β–arrestin pathways that have been described in other cell types and might also occur in somatosensory neurons (Gendron et al. 2015; Dang and Christie 2012; Pradhan et al. 2011; Lamberts and Traynor 2013; Zaki et al. 1996; Cahill et al. 2016; Gendron et al. 2016; Charfi et al. 2015; Fujita et al. 2014; Pradhan et al. 2012; Georgoussi 2015; Al-Hasani and Bruchas 2011; Gaveriaux-Ruff and Kieffer 2011; Zollner and Stein 2007).

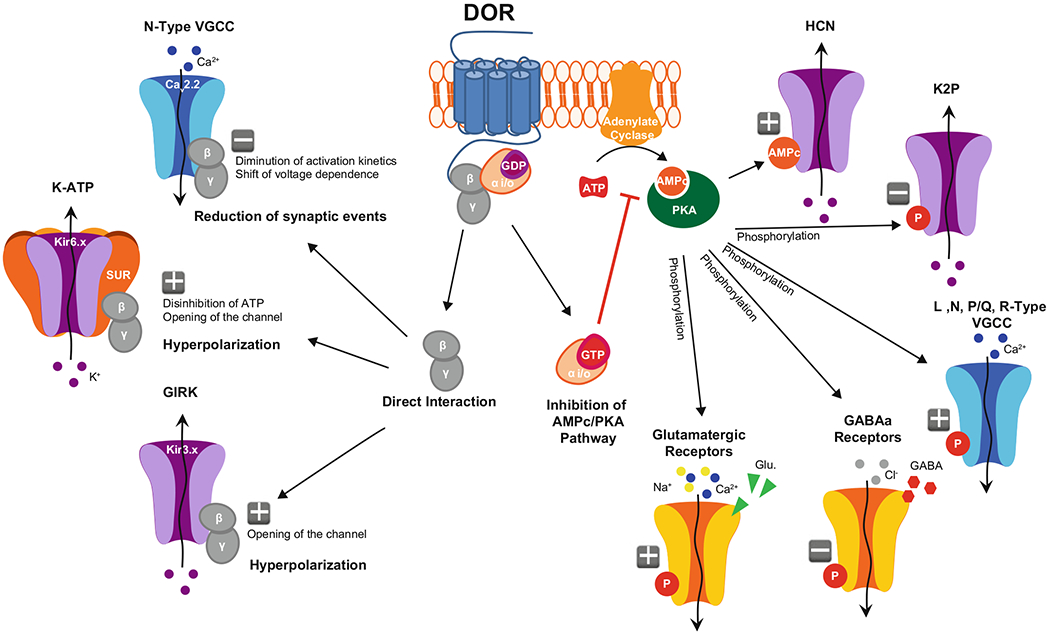

Fig. 4.

Putative ion channel mechanisms engaged by DOR in DRG neurons. Binding of endogenous or exogenous DOR agonists activates G proteins. Subsequent separation of the G protein subunits triggers distinct signaling cascades: on the left, direct interaction of Gβγ with N-Type VGCCs leads to reduced calcium current amplitude and decreased neurotransmitter release, while direct interaction with GIRK and/or KATP channels increases potassium conductance, resulting in membrane hyperpolarization. On the right, inhibition of adenylate cyclase by Gαi/o reduces cAMP production and PKA activation, which alters the phosphorylation states of different receptors and ion channels and leads to decreased excitability

3.1. Inhibition of Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels

Voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) are activated by depolarization of the plasma membrane, resulting in calcium flow into the cell (i.e., inward current). While this increase in intracellular calcium can contribute to action potential (AP) generation (Fatt and Katz 1953), its main purpose in mammals is to couple electrical excitation to calcium-dependent intracellular mechanisms, including synaptic vesicle fusion for neurotransmitter release. VGCCs are composed of a main α subunit that forms the pore of the channel. This protein is comprised of four repeated domains that each contain six transmembrane segments (TM) and several intracellular loops (IL) with residues for protein interactions and posttranslational modifications (Tanabe et al. 1987). The α subunit requires an additional intracellular β subunit and an extracellular α2δ subunit to form a functional VGCC (except for T-type VGCCs, which lack the β subunit). β and α2δ subunits modulate membrane expression, opening probability, and voltage dependence of the α subunit (Arikkath and Campbell 2003). Ten genes code for the α subunit and form three families of VGCCs (types) with distinct distributions and functions: L-type VGCCs (Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3, Cav1.4); P/Q, N, and R-type VGCCs (Cav2.1, Cav2.2, and Cav2.3); and T-type VGCCs (Cav3.1, Cav3.2, Cav3.3) (Catterall 2011; Simms and Zamponi 2014; Zamponi 2016).

L-type, T-type, and most importantly, P/Q and N-type, VGCCs have been functionally described in DRG neurons of various species (Evans et al. 1996; Heinke et al. 2004; Murakami et al. 2001; Nowycky et al. 1985). Cav2.1 (P/Q) and Cav2.2 (N-type) appear to be particularly important for synaptic transmission between primary afferent somatosensory neurons and spinal cord neurons (Simms and Zamponi 2014). Cav2.1 is highly expressed in large-diameter DRG neurons, while Cav2.2 is preferentially found in small-diameter DRG neurons (Bell et al. 2004; Murali et al. 2015; Saegusa et al. 2001; Yusaf et al. 2001). Both Cav2.1 and Cav2.2 are localized in axon presynaptic terminals. Action potentials cause the opening of the channel and calcium influx at close proximity of the SNAP-SNARE complex. This local increase in calcium concentration triggers the fusion of synaptic vesicles with the plasma membrane for neurotransmitter release (Sudhof 2004). Approximately 45% and 15% of the total DRG VGCC current is thought to be conducted through Cav2.2 and Cav2.1, respectively (Wilson et al. 2000). The Cav2.2 α subunit possesses a crucial sequence for opioid receptor-mediated inhibition, in the intracellular loop (IL1) between the TM I and II. Following opioid receptor activation, dissociation, and binding of the βγ subunits of Gi/o proteins (Gβγ) to this site causes a shift in the voltage dependence of calcium channel activation to more positive membrane potentials and slows down the activation kinetics of the Cav2.2 current, resulting in reduced neurotransmitter release (Herlitze et al. 1997; Ikeda 1996). For opioid receptor-mediated inhibition to occur, opioid receptors and VGCCs need to be close to each other. Additionally, opioid receptor-mediated modulation of VGCCs is voltage dependent: depolarization (e.g., during a train of action potentials) causes Gβγ to dissociate from the channel and drastically reduces inhibition. Because IL1 is also important for interactions between Cav2.2 α and β subunits, Gβγ binding may displace Cav2.2 β due to steric hindrance, which also contributes to Gβγ inhibition of VGCCs (Buraei and Yang 2010). Note that other GPCRs, coupled to Gq or Gs proteins, can positively regulate VGCCs, including through the recruitment of kinases that phosphorylate the channel and counteract opioids’ inhibition of calcium influx (Zamponi et al. 1997). Cav2.2 is important not only for glutamate release but also for the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P, two major pro-nociceptive neuropeptides (Evans et al. 1996; Brittain et al. 2011; Westenbroek et al. 1998).

While a wealth of studies has demonstrated MOR-meditated inhibition of VGCCs in DRG neurons (Schroeder et al. 1991; Moises et al. 1994; Wu et al. 2004; Schroeder and McCleskey 1993; Raingo et al. 2007; Jiang et al. 2013; Pan et al. 2008) particularly in small-diameter nociceptors, DOR coupling to VGCCs remains controversial. Thus, several studies reported that DOR agonists only minimally impact calcium current amplitude and kinetics in DRG neurons from naive rodents (i.e., uninjured) (Walwyn et al. 2005; Pradhan et al. 2013; Brackley et al. 2016; Acosta and Lopez 1999; Wu et al. 2008). Another interpretation of these data, however, is that most of the cells patched in these studies did not belong to the class of DRG neurons that normally express DOR. Indeed, blind recording approaches (i.e., unidentified cells) are unlikely to randomly select DOR-expressing neurons in the cultures used. First, DOR is expressed by fewer neurons in DRG, compared to MOR, for example. Second, the methods used to culture DRG neurons generally select for small-diameter neurons, in particular peptidergic, when NGF, the TrkA agonist that promotes the survival and growth of this class of DRG neurons, is present in the culture medium. Because they are more sensitive to enzymatic and mechanical dissociation, and because factors necessary for their survival (GDNF, neurotrophin 3, neurotrophin 4) are rarely included in the medium, large-diameter neurons are most often rare in these cultures and not recorded. Consistent with this interpretation, Bardoni et al. reported, in acutely dissociated DRG neurons from wild-type mice, that the DOR agonist deltorphin II inhibits VGCCs both in a subset of large-diameter and small-diameter IB4-binding DRG neurons, but very rarely in IB4-negative (presumably peptidergic) small-diameter neurons. Furthermore, DOR agonists reduce the amplitude of EPSCs evoked in dorsal horn neurons by stimulation of primary afferents, in particular A fiber-mediated EPSCs in laminae III-V (Bardoni et al. 2014; Glaum et al. 1994; Fan et al. 1993; Rogers and Henderson 1990). Because the reduction in amplitude was accompanied by an increase in paired-pulse ratio, this result establishes that DOR inhibits neurotransmitter release from A fibers, presumably through inhibition of VGCCs at their terminals (Bardoni et al. 2014). Similarly, release of the endogenous DOR agonist enkephalin in the spinal cord reduces A fiber input, and suppression of enkephalin release induces mechanical pain (Francois et al. 2017), suggesting that endogenous DOR signaling also inhibits VGCCs presynaptically to gate mechanical pain. DORGFP fusion receptor, either endogenously expressed by acutely dissociated DRG neurons (Bardoni et al. 2014) or heterogeneously expressed in cultured neurons (Pettinger et al. 2013), also inhibited VGCCs following application of DOR agonist. Finally, studies that demonstrated that DOR agonists reduce CGRP release (Overland et al. 2009; Patwardhan et al. 2006) also support the idea that DOR inhibits VGCCs, regardless of the origin of this effect (i.e., small- versus large-diameter CGRP+ DRG neurons). Data reporting a decrease in substance P release by DOR agonists (Kouchek et al. 2013; Normandin et al. 2013; Zachariou and Goldstein 1996) are more difficult to interpret given that substance P, contrary to CGRP, is also expressed by spinal cord neurons (Gutierrez-Mecinas et al. 2014). DOR function can be upregulated in a variety of regions and conditions (see Gendron et al. 2015 for review). Of particular interest are the studies that showed increased DOR function and coupling to VGCCs in DRG neurons. Thus, inflammation and bradykinin can augment the efficacy of DOR agonists to inhibit VGCCs (Walwyn et al. 2005; Pradhan et al. 2013; Brackley et al. 2016; Mittal et al. 2013) or the proportion of DRG neurons in which this inhibitory effect is seen (Pettinger et al. 2013). The mechanisms underlying this gain in function are actively investigated, and recent studies suggest that receptor export and signaling molecules controlling receptor desensitization and trafficking such as GRK2 and β–arrestin 1 are involved (Brackley et al. 2016; Pettinger et al. 2013; Mittal et al. 2013; Gendron et al. 2006).

3.2. Activation of Inward-Rectifier Potassium Channels

Potassium channels represent a family of more than 80 genes that can be divided in six major classes: voltage-gated with six TM (Kv), inwardly rectifier with two TM (Kir), tandem pore domain with 4 TM (K2P), and calcium-activated BK, Sk, and IK channels (Yu and Catterall 2004). Among them, Kir potassium channels are particularly important for opioid modulation of cell excitability. Kirs are composed of four main α subunits that form the pore of the channel. Each α subunit comprises 2 TMs, and intracellular N- and C-terminals. Opening of Kir channels leads to potassium flowing out of the cell (i.e., outward current), which hyperpolarizes the membrane, reducing excitability and synaptic transmission (Hille 1992). In DRG neurons, two main families of Kir have been described: ATP-sensitive (KATP) and G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels.

KATP channels are gated by ATP (Kir6.x family) and are composed of four Kir6.1 and/or Kir6.2 subunits, supplemented by four SUR 1 and/or two (sulfonylurea receptor) subunits. The SUR subunits are 17 TM proteins, containing two nucleotide-binding sites that act as ATP sensors. At cellular physiological concentration, ATP binding to these sites results in inhibition of Kir6.x channel opening (Aguilar-Bryan et al. 1998). Gβγ proteins can also interact with these sites. Following activation of G proteins, Gβγ binds to SUR and decreases the inhibition by ATP, resulting in facilitation of Kir6.x channels opening (Wada et al. 2000). Immunohistochemical studies suggest that Kir6.2, SUR1, and SUR2 are expressed in DRG neurons in rats (Kawano et al. 2009a; Zoga et al. 2010). Consistent with this, functional evidence suggests that KATP currents can inhibit substance P release from rat DRG neurons (Ohkubo and Shibata 1995; Sarantopoulos et al. 2003). Furthermore, KATP activation has been shown to reduce mechanical and thermal nociception in naïve mice, and following inflammatory and neuropathic pain induced by bradykinin and axotomy, respectively (Zoga et al. 2010; Du et al. 2011; Kawano et al. 2009b; Pacheco and Duarte 2005). Several studies demonstrated that peripheral morphine antinociception involves KATP activation, linking opioid receptors to these channels (Afify et al. 2013; Cunha et al. 2010; Rodrigues and Duarte 2000). In a similar way, it appears that antinociception caused by DOR agonists can derive from KATP activation (Gutierrez et al. 2012; Pena-dos-Santos et al. 2009; Saloman et al. 2011). Whether these observations result from direct binding of Gβγ dissociated from DOR following its activation remains unclear. To note, most of these studies were performed in rats, it is unclear that opioid receptor signaling involving KATP channels is conserved in DRG from other species, particularly mice and humans.

GIRK channels are directly regulated by Gi/o proteins (Kir3.x family) (Ocana et al. 2004). GIRK channels are comprised of four α subunits, each with two 2 TMs and intracellular C- and N-terminals, which interact with Gβγ. In the absence of G protein interaction, the C- and N-terminus maintain the channel in a closed conformation. Following G protein activation, binding of Gβγ to the intracellular domains switches the channel to an open conformation (Mark and Herlitze 2000). Four genes encode different α subunits: Kir3.1 to Kir3.4 (also named GIRK1 to GIRK 4). To form a functional pore, α subunits are assembled into homo- or hetero-tetramers. The combination of these four subunits influences the properties of the channel. GIRK1 needs to be associated with another class of GIRK α subunit to form a functional potassium current (i.e., obligatory heteromer) (Jelacic et al. 2000; Kennedy et al. 1996; Lesage et al. 1995). GIRK channels are widely distributed in the CNS and represent major effectors of opioid receptors in neurons, including for DOR. In DRG neurons, on the other hand, the expression of GIRK channels remains debated. An RT-PCR and electrophysiological analysis suggested that GIRK 1 through 4 are expressed in rat DRG (Gao et al. 2007). Furthermore, a recent study not only confirmed that GIRK channels are present in DRG but also showed that GIRK2 critically contributes to peripheral morphine analgesia in rats and humans (Nockemann et al. 2013). In this article, the authors also provide evidence that GIRK channels are not expressed in mouse DRG. If GIRK channels are present in DOR-expressing DRG neurons, they likely are modulated by DOR. Very few studies have explored this possibility. Regarding DOR modulation of GIRK, DOR agonists can activate GIRK 1 and 2 in rat trigeminal ganglia (Chung et al. 2014).

3.3. Indirect Modulation of Ion Channels

DOR may also indirectly control ion channel opening and neuron excitability, through Gi/o, Gs or Gq modulation of phosphorylation of ion channels by PKA, PKC, or phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2), and diacylglycerol (DAG) abundance.

Opioid receptors regulate the activity of adenylate cyclase (AC) (Nestler 2004; Gilman 1987). AC produces cAMP, a second messenger that activates downstream effectors, particularly protein kinase A (PKA). PKA phosphorylates proteins and modifies their properties, including ion channels and receptors that regulate neuronal excitability. Early studies in cell lines established that opioid receptors, including DOR, inhibit AC via Gαi/o (Prather et al. 1994; Roerig et al. 1992; Wong et al. 1992; Wong et al. 1991). This effect, however, seems dependent on the neuronal context. Thus, while activation of DOR or MOR results in AC inhibition in neurons in numerous brain regions (Buzas et al. 1994; Chneiweiss et al. 1988; Eybalin et al. 1987; Izenwasser et al. 1993; Law et al. 1981), an increase in AC was reported in the olfactory bulb, spinal cord explant, and DRG (Makman et al. 1988; Olianas and Onali 1995; Shen and Crain 1989). In DRG, these studies revealed that activation of opioid receptors, including DOR, can lead to a dual modulation, i.e., inhibitory via Gi/o or excitatory via Gs, of AC, depending on the dose of agonists used (Fan et al. 1993; Crain and Shen 1990; Tang et al. 1995). More recently, AC activation by morphine has been proposed to contribute to morphine tolerance and withdrawal, via a Gs-mediated increase of TRPV1 activity and CGRP release (Spahn et al. 2013; Tumati et al. 2011; Tumati et al. 2010; Yue et al. 2008). Recent research on the topic is lacking, and no study has specifically examined DOR coupling to AC in DRG neurons that endogenously express this opioid receptor. DOR activation in DRG neurons can potentially modulate all targets downstream of cAMP and PKA, including receptors or ion channels such as hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) and two pore domain (K2P or K+ leak) channels (see below). Note that in addition to the classical Gβγ inhibition, VGCC activity can be modulated by PKA phosphorylation, especially for L-Type channels (Altier and Zamponi 2008; Sculptoreanu et al. 1993). L-Type calcium channels are expressed in small- and large-diameter DRG neurons (Scroggs and Fox 1992) and may be indirectly regulated by DOR.

HCN channels carry a Na+ K+ inward current and are activated by membrane hyperpolarization (−60 to −90 mV). Opening of HCN channels elicits membrane depolarization toward the threshold for action potential generation. In neurons, HCN channels are notably responsible for rhythmicity in pacemaker cells and contribute to rebound activity and resting potential (Biel et al. 2009). Importantly, HCN channel opening is facilitated by binding of cAMP (i.e., in a PKA-independent manner) and is indirectly modulated by GPCRs controlling AC activity. In DRG, HCN 1 and 3 are thought to be expressed by Aβ and Aδ fibers, whereas HCN2 is predominantly expressed by C nociceptors and reportedly contributes to inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Emery et al. 2011; Momin et al. 2008; Weng et al. 2012). It follows that if DOR is coupled to AC and alters cAMP concentration in DRG neurons, DOR agonist antinociceptive activity may involve modulation of HCN channel activity. Among K2P channels, TREK-1, TREK-2, TRAAK, and TRESK channels are of particular interest. These channels determine neuron resting potential and, in DRG neurons, sensitivity to mechanical and thermal stimuli (Alloui et al. 2006; Brohawn et al. 2014; Honore 2007; Noel et al. 2009). All types of DRG neurons are thought to express some isoform of TREK and/or TRESK (Alloui et al. 2006; Kang and Kim 2006). TREK channels are inhibited by PKA and PKC phosphorylation, hydrolysis of PtdIns(4, 5)P2, DAG (Honore 2007), potentially linking TREK function to DOR signaling in DRG neurons. Consistent with this idea, a recent study described a direct link between MOR activation and TREK-1 activation (Devilliers et al. 2013).

4. Conclusion: Implications for DOR Function in Somatosensation and Pain Control

The characterization of DOR+ DRG neurons has so far revealed that many of these cells have the molecular identity and anatomical properties of cutaneous mechanosensory neurons known to initiate the perception of touch and mechanical pain. The mechanosensitivity of DOR+ DRG neurons was directly demonstrated by electrophysiological recording using an ex vivo somatosensory system preparation in which the skin, cutaneous nerve, DRGs, and spinal cord are dissected in continuity (Koerber and Woodbury 2002). DORGFP+ DRG neurons did not respond to noxious heat applied to the skin, but were very sensitive and fired vigorously in response to stimulation with a mechanical probe (Bardoni et al. 2014). These studies also revealed the existence of several types of DOR+ myelinated mechanosensory afferents, with distinct conduction velocities (covering Aδ and Aβ range) and thresholds (firing in response to innocuous and/or noxious mechanical stimulation).

The signaling and ion channel mechanisms engaged by DOR in DRG neurons generally result in a reduction in cell excitability and/or neurotransmitter release. In other words, DOR activation in DRG is expected to reduce the perception of the somatosensory modalities encoded by the DRG neurons in which the receptor is predominantly expressed: touch and mechanical pain. A large number of studies have thus reported that DOR agonists reduce cutaneous mechanical sensitivity, both acutely (Scherrer et al. 2009; Normandin et al. 2013; Pacheco and Duarte 2005; Pacheco Dda et al. 2012; Fuchs et al. 1999; Cao et al. 2001) and in the context of hypersensitivity (i.e., allodynia) induced by nerve or tissue injuries (i.e., chronic inflammatory or neuropathic pain) (Scherrer et al. 2009; Joseph and Levine 2010; Pradhan et al. 2013; Kouchek et al. 2013; Saloman et al. 2011; Cao et al. 2001; Sluka et al. 2002; Desmeules et al. 1993; Gaveriaux-Ruff et al. 2011; Stewart and Hammond 1994; Kabli and Cahill 2007; Obara et al. 2009; Nozaki et al. 2012; Gaveriaux-Ruff et al. 2008; Stein et al. 1989; Zhou et al. 1998; Hervera et al. 2010; Otis et al. 2011; Pradhan et al. 2009; Le Bourdonnec et al. 2009). The antinociceptive properties of DOR agonists in rodent pain models led researchers to propose that DOR agonists were particularly useful against chronic pain compared to acute pain (Gaveriaux-Ruff and Kieffer 2011; Pradhan et al. 2013; Stewart and Hammond 1994; Kabli and Cahill 2007; Cahill et al. 2007; Vanderah 2010; Hurley and Hammond 2000). The emergence of this concept results, in part, from the fact that cutaneous mechanical sensitivity has long been evaluated almost exclusively in animals with neuropathic or inflammatory hypersensitivity, but very rarely acutely in healthy uninjured animals. By contrast, in most studies before the mid-2000s ((re)emergence of the concept of pain modalities and peripheral nociceptive labelled lines (Ma 2010; Craig 2003; Pereira and Alves 2011; Emery et al. 2016)), acute sensitivity in healthy animals was measured using heat as a noxious stimulus. It is clear today that evaluating cutaneous mechanical sensitivity in the setting of injury probes the function of A LTMRs that normally encode touch and not only nociceptors. Following injury, loss of inhibition in dorsal horn circuits enables polysynaptic neurotransmission between A LTMRs and nociceptive neurons, resulting in innocuous mechanical stimulation being perceived as painful (i.e., mechanical allodynia) (Basbaum et al. 2009; Sandkuhler 2009). It is very likely that the anti-allodynic properties of DOR agonists result from the beneficial reduction in neurotransmitter release from A LTMRs. DOR activation in A LTMRs detecting movements across the skin, and in A LTMRs/A HTMRs/MrgprD+ C nociceptors responding to skin indentation, could alleviate dynamic and static allodynia, respectively. Note that DOR expression in A LTMRs suggests that DOR may also modulate mechanosensation in the absence of injury; however, evaluating touch perception in rodents remains challenging. To our knowledge no studies have yet evaluated the impact of DOR activation or knockout on touch modalities encoded by the different A LTMRs expressing DOR (e.g., movement across the skin, vibrations, texture coding).

Much work is still needed to determine if DOR is expressed by other types of afferents, innervating other tissues (e.g., muscle or bone), or coding other somatosensory modalities (e.g. itch), and how tissue and nerve injury impact DOR expression and signaling in DRG during inflammatory and neuropathic chronic pain. Similarly, analyzing DOR distribution in trigeminal ganglia and DOR signaling at the peripheral terminals might uncover new therapeutic indications for DOR agonists. Finally, DOR is expressed by a variety of neurons in brain regions processing somatosensory information, such as the amygdala and prefrontal/cingulate cortices. Future studies will resolve DOR function in these regions and establish its contribution to shaping pain experience, including attribution of negative emotional valence (e.g., pain unpleasantness), execution of motivated behaviors (e.g., avoidance), and cognitive and psychological maladaptations (e.g., pain catastrophizing, mood disorders).

Acknowledgments

G.S. was supported by NIH/NIDA grant DA031777 and a Rita Allen Foundation and American Pain Society award. A.F. was supported by a Stanford Dean’s fellowship. We thank Dr. Dong Wang for providing unpublished in situ hybridization images (Fig. 1a, b), and Elizabeth Sypek and Dr. Kristen Hymel Scherrer for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- Abraira VE, Ginty DD (2013) The sensory neurons of touch. Neuron 79:618–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta CG, Lopez HS (1999) Delta opioid receptor modulation of several voltage-dependent Ca(2+) currents in rat sensory neurons. J Neurosci 19:8337–8348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afify EA, Khedr MM, Omar AG, Nasser SA (2013) The involvement of K(ATP) channels in morphine-induced antinociception and hepatic oxidative stress in acute and inflammatory pain in rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 27:623–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Bryan L et al. (1998) Toward understanding the assembly and structure of KATP channels. Physiol Rev 78:227–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hasani R, Bruchas MR (2011) Molecular mechanisms of opioid receptor-dependent signaling and behavior. Anesthesiology 115:1363–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloui A et al. (2006) TREK-1, a K+ channel involved in polymodal pain perception. EMBO J 25:2368–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier C, Zamponi GW (2008) Signaling complexes of voltage-gated calcium channels and G protein-coupled receptors. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 28:71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez FJ, Kavookjian AM, Light AR (1992) Synaptic-interactions between gaba-immunoreactive profiles and the terminals of functionally defined myelinated nociceptors in the monkey and cat spinal-cord. J Neurosci 12:2901–2917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcourt A et al. (2017) Touch receptor-derived sensory information alleviates acute pain signaling and fine-tunes nociceptive reflex coordination. Neuron 93:179–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikkath J, Campbell KP (2003) Auxiliary subunits: essential components of the voltage-gated calcium channel complex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 13:298–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson U et al. (1995) Delta-opioid receptor immunoreactivity: distribution in brainstem and spinal cord, and relationship to biogenic amines and enkephalin. J Neurosci 15:1215–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L et al. (2015) Genetic identification of an expansive mechanoreceptor sensitive to skin stroking. Cell 163:1783–1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L et al. (2003) Activation of delta opioid receptors induces receptor insertion and neuropeptide secretion. Neuron 37:121–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardoni R et al. (2014) Delta opioid receptors presynaptically regulate cutaneous mechanosensory neuron input to the spinal cord dorsal horn. Neuron 81:1312–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D (2009) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 139:267–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell TJ, Thaler C, Castiglioni AJ, Helton TD, Lipscombe D (2004) Cell-specific alternative splicing increases calcium channel current density in the pain pathway. Neuron 41:127–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel M, Wahl-Schott C, Michalakis S, Zong X (2009) Hyperpolarization-activated cation channels: from genes to function. Physiol Rev 89:847–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackley AD, Gomez R, Akopian AN, Henry MA, Jeske NA (2016) GRK2 constitutively governs peripheral delta opioid receptor activity. Cell Rep 16:2686–2698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain JM et al. (2011) Suppression of inflammatory and neuropathic pain by uncoupling CRMP-2 from the presynaptic Ca(2)(+) channel complex. Nat Med 17:822–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohawn SG, Su Z, MacKinnon R (2014) Mechanosensitivity is mediated directly by the lipid membrane in TRAAK and TREK1 K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:3614–3619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z, Yang J (2010) The ss subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol Rev 90:1461–1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzas B, Cox BM (1997) Quantitative analysis of mu and delta opioid receptor gene expression in rat brain and peripheral ganglia using competitive polymerase chain reaction. Neuroscience 76:479–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzas B, Izenwasser S, Portoghese PS, Cox BM (1994) Evidence for delta opioid receptor subtypes regulating adenylyl cyclase activity in rat brain. Life Sci 54:PL101–PL106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill CM et al. (2001) Immunohistochemical distribution of delta opioid receptors in the rat central nervous system: evidence for somatodendritic labeling and antigen-specific cellular compartmentalization. J Comp Neurol 440:65–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill CM, Holdridge SV, Morinville A (2007) Trafficking of delta-opioid receptors and other G-protein-coupled receptors: implications for pain and analgesia. Trends Pharmacol Sci 28:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill CM, Walwyn W, Taylor AMW, Pradhan AAA, Evans CJ (2016) Allostatic mechanisms of opioid tolerance beyond desensitization and down regulation. Trends Pharmacol Sci 37:963–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao CQ, Hong Y, Dray A, Perkins M (2001) Spinal delta-opioid receptors mediate suppression of systemic SNC80 on excitability of the flexor reflex in normal and inflamed rat. Eur J Pharmacol 418:79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA (2011) Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3:a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh DJ et al. (2009) Distinct subsets of unmyelinated primary sensory fibers mediate behavioral responses to noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:9075–9080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh DJ et al. (2011) Restriction of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 to the peptidergic subset of primary afferent neurons follows its developmental downregulation in nonpeptidergic neurons. J Neurosci 31:10119–10127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charfi I, Audet N, Tudashki HB, Pineyro G (2015) Identifying ligand-specific signalling within biased responses: focus on delta opioid receptor ligands. Br J Pharmacol 172:435–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chneiweiss H, Glowinski J, Premont J (1988) Mu and delta opiate receptors coupled negatively to adenylate cyclase on embryonic neurons from the mouse striatum in primary cultures. J Neurosci 8:3376–3382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MK et al. (2014) Peripheral G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels are involved in delta-opioid receptor-mediated anti-hyperalgesia in rat masseter muscle. Eur J Pain 18:29–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD (2003) Pain mechanisms: labeled lines versus convergence in central processing. Annu Rev Neurosci 26:1–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain SM, Shen KF (1990) Opioids can evoke direct receptor-mediated excitatory effects on sensory neurons. Trends Pharmacol Sci 11:77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha TM et al. (2010) Morphine peripheral analgesia depends on activation of the PI3Kgamma/AKT/nNOS/NO/KATP signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:4442–4447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dado RJ, Law PY, Hoh HH, Elde R (1993) Immunofluorescent identification of a delta ([delta])-opioid receptor on primary afferent nerve terminals. Neuroreport 5:341–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang VC, Christie MJ (2012) Mechanisms of rapid opioid receptor desensitization, resensitization and tolerance in brain neurons. Br J Pharmacol 165:1704–1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schepper HU et al. (2008) TRPV1 receptor signaling mediates afferent nerve sensitization during colitis-induced motility disorders in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G245–G253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfini MC et al. (2013) TAFA4, a chemokine-like protein, modulates injury-induced mechanical and chemical pain hypersensitivity in mice. Cell Rep 5:378–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P, Hao J, Rodat-Despoix L (2011) Molecular mechanisms of mechanotransduction in mammalian sensory neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 12:139–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmeules JA, Kayser V, Guilbaud G (1993) Selective opioid receptor agonists modulate mechanical allodynia in an animal model of neuropathic pain. Pain 53:277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilliers M et al. (2013) Activation of TREK-1 by morphine results in analgesia without adverse side effects. Nat Commun 4:2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nooij JC, Doobar S, Jessell TM (2013) Etv1 inactivation reveals proprioceptor subclasses that reflect the level of NT3 expression in muscle targets. Neuron 77:1055–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Wang C, Zhang H (2011) Activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels antagonize nociceptive behavior and hyperexcitability of DRG neurons from rats. Mol Pain 7:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussor G, Zylka MJ, Anderson DJ, McCleskey EW (2008) Cutaneous sensory neurons expressing the Mrgprd receptor sense extracellular ATP and are putative nociceptors. J Neurophysiol 99:1581–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert WA III, Light AR (2002) Hyperpolarization of substantia gelatinosa neurons evoked by mu-, kappa-, delta 1-, and delta 2-selective opioids. J Pain 3:115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery EC, Young GT, Berrocoso EM, Chen L, McNaughton PA (2011) HCN2 ion channels play a central role in inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Science 333:1462–1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery EC et al. (2016) In vivo characterization of distinct modality-specific subsets of somatosensory neurons using GCaMP. Sci Adv 2:e1600990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CJ, Keith DE Jr, Morrison H, Magendzo K, Edwards RH (1992) Cloning of a delta opioid receptor by functional expression. Science 258:1952–1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AR, Nicol GD, Vasko MR (1996) Differential regulation of evoked peptide release by voltage-sensitive calcium channels in rat sensory neurons. Brain Res 712:265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eybalin M, Pujol R, Bockaert J (1987) Opioid receptors inhibit the adenylate cyclase in guinea pig cochleas. Brain Res 421:336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan SF, Shen KF, Crain SM (1993) Mu and delta-opioid agonists at low concentrations decrease voltage-dependent K+ currents in F11 neuroblastoma X drug neuron hybrid-cells via cholera toxin-sensitive receptors. Brain Res 605:214–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatt P, Katz B (1953) The electrical properties of crustacean muscle fibres. J Physiol 120:171–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Emson PC, Leigh BK, Gilbert RF, Iversen LL (1980) Multiple opiate receptor sites on primary afferent fibres. Nature 284:351–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filliol D et al. (2000) Mice deficient for delta- and gamma-opioid receptors exhibit opposing alterations of emotional responses. Nat Genet 25:195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck MC et al. (2011) Essential role of ret for defining non-peptidergic nociceptor phenotypes and functions in the adult mouse. Eur J Neurosci 33:1385–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois A et al. (2017) A brainstem-spinal cord inhibitory circuit for mechanical pain modulation by GABA and enkephalins. Neuron 93(4):822–839. e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs PN, Roza C, Sora I, Uhl G, Raja SN (1999) Characterization of mechanical withdrawal responses and effects of mu-, delta- and kappa-opioid agonists in normal and mu-opioid receptor knockout mice. Brain Res 821:480–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita W, Gomes I, Devi LA (2014) Revolution in GPCR signalling: opioid receptor heteromers as novel therapeutic targets: IUPHAR review 10. Br J Pharmacol 171:4155–4176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XF, Zhang HL, You ZD, Lu CL, He C (2007) G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Acta Pharmacol Sin 28:185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Kieffer BL (2011) Delta opioid receptor analgesia: recent contributions from pharmacology and molecular approaches. Behav Pharmacol 22:405–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Karchewski LA, Hever X, Matifas A, Kieffer BL (2008) Inflammatory pain is enhanced in delta opioid receptor-knockout mice. Eur J Neurosci 27:2558–2567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaveriaux-Ruff C et al. (2011) Genetic ablation of delta opioid receptors in nociceptive sensory neurons increases chronic pain and abolishes opioid analgesia. Pain 152:1238–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron L et al. (2006) Morphine and pain-related stimuli enhance cell surface availability of somatic delta-opioid receptors in rat dorsal root ganglia. J Neurosci 26:953–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron L, Mittal N, Beaudry H, Walwyn W (2015) Recent advances on the delta opioid receptor: from trafficking to function. Br J Pharmacol 172:403–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron L, Cahill CM, von Zastrow M, Schiller PW, Pineyro G (2016) Molecular pharmacology of delta-opioid receptors. Pharmacol Rev 68:631–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgoussi Z (2015) The other side of opioid receptor signaling: regulation by protein-protein interaction. Spring 4:L21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghitani N et al. (2017) Specialized mechanosensory nociceptors mediating rapid responses to hair pull. Neuron 95:944–954. e944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman AG (1987) G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem 56:615–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum SR, Miller RJ, Hammond DL (1994) Inhibitory actions of delta 1-, delta 2-, and mu-opioid receptor agonists on excitatory transmission in lamina II neurons of adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci 14:4965–4971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goody RJ, Oakley SM, Filliol D, Kieffer BL, Kitchen I (2002) Quantitative autoradiographic mapping of opioid receptors in the brain of delta-opioid receptor gene knockout mice. Brain Res 945:9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami SC et al. (2014) Molecular signatures of mouse TRPV1-lineage neurons revealed by RNA-Seq transcriptome analysis. J Pain 15:1338–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan JS et al. (2005) Interaction with vesicle luminal protachykinin regulates surface expression of delta-opioid receptors and opioid analgesia. Cell 122:619–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez VP et al. (2012) The peripheral L-arginine-nitric oxide-cyclic GMP pathway and ATP-sensitive K(+) channels are involved in the antinociceptive effect of crotalphine on neuropathic pain in rats. Behav Pharmacol 23:14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Mecinas M, Watanabe M, Todd AJ (2014) Expression of gastrin-releasing peptide by excitatory interneurons in the mouse superficial dorsal horn. Mol Pain 10:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinke B, Balzer E, Sandkuhler J (2004) Pre- and postsynaptic contributions of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels to nociceptive transmission in rat spinal lamina I neurons. Eur J Neurosci 19:103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Hockerman GH, Scheuer T, Catterall WA (1997) Molecular determinants of inactivetion and G protein modulation in the intracellular loop connecting domains I and II of the calcium channel alpha1A subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:1512–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervera A, Negrete R, Leanez S, Martin-Campos J, Pol O (2010) The role of nitric oxide in the local antiallodynic and antihyperalgesic effects and expression of delta-opioid and cannabinoid-2-receptors during neuropathic pain in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334:887–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B (1992) Ionic channels of excitable membranes, 2nd edn Sinauer Associates, Inc, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- Holmseth S et al. (2012) Specificity controls for immunocytochemistry: the antigen preadsorption test can lead to inaccurate assessment of antibody specificity. J Histochem Cytochem 60:174–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honore E (2007) The neuronal background K2P channels: focus on TREK1. Nat Rev Neurosci 8:251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RW, Hammond DL (2000) The analgesic effects of supraspinal mu and delta opioid receptor agonists are potentiated during persistent inflammation. J Neurosci 20:1249–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda SR (1996) Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature 380:255–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izenwasser S, Buzas B, Cox BM (1993) Differential regulation of adenylyl cyclase activity by mu and delta opioids in rat caudate putamen and nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 267:145–152 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski MP, Rau KK, Ekmann KM, Anderson CE, Koerber HR (2013) Comprehensive phenotyping of group III and IV muscle afferents in mouse. J Neurophysiol 109:2374–2381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelacic TM, Kennedy ME, Wickman K, Clapham DE (2000) Functional and biochemical evidence for G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels composed of GIRK2 and GIRK3. J Biol Chem 275:36211–36216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang YQ, Andrade A, Lipscombe D (2013) Spinal morphine but not ziconotide or gabapentin analgesia is affected by alternative splicing of voltage-gated calcium channel CaV2.2 pre-mRNA. Mol Pain 9:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RC III, Xu L, Gebhart GF (2005) The mechanosensitivity of mouse colon afferent fibers and their sensitization by inflammatory mediators require transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 and acid-sensing ion channel 3. J Neurosci 25:10981–10989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph EK, Levine JD (2010) Mu and delta opioid receptors on nociceptors attenuate mechanical hyperalgesia in rat. Neuroscience 171:344–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabli N, Cahill CM (2007) Anti-allodynic effects of peripheral delta opioid receptors in neuropathic pain. Pain 127:84–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Kim D (2006) TREK-2 (K2P10.1) and TRESK (K2P18.1) are major background K+ channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Am J Phys Cell Physiol 291:C138–C146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T et al. (2009a) ATP-sensitive potassium currents in rat primary afferent neurons: biophysical, pharmacological properties, and alterations by painful nerve injury. Neuroscience 162:431–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T et al. (2009b) Suppressed Ca2+/CaM/CaMKII-dependent K(ATP) channel activity in primary afferent neurons mediates hyperalgesia after axotomy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:8725–8730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy ME, Nemec J, Clapham DE (1996) Localization and interaction of epitope-tagged GIRK1 and CIR inward rectifier K+ channel subunits. Neuropharmacology 35:831–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer BL, Befort K, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Hirth CG (1992) The delta-opioid receptor: isolation of a cDNA by expression cloning and pharmacological characterization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:12048–12052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen I, Slowe SJ, Matthes HW, Kieffer B (1997) Quantitative autoradiographic mapping of mu-, delta- and kappa-opioid receptors in knockout mice lacking the mu-opioid receptor gene. Brain Res 778:73–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber HR, Woodbury CJ (2002) Comprehensive phenotyping of sensory neurons using an ex vivo somatosensory system. Physiol Behav 77:589–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziejczyk AA, Kim JK, Svensson V, Marioni JC, Teichmann SA (2015) The technology and biology of single-cell RNA sequencing. Mol Cell 58:610–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchek M, Takasusuki T, Terashima T, Yaksh TL, Xu Q (2013) Effects of intrathecal SNC80, a delta receptor ligand, on nociceptive threshold and dorsal horn substance p release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 347:258–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemend F, Ernfors P (2012) Molecular interactions underlying the specification of sensory neurons. Trends Neurosci 35:373–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberts JT, Traynor JR (2013) Opioid receptor interacting proteins and the control of opioid signaling. Curr Pharm Design 19:7333–7347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law PY, Wu J, Koehler JE, Loh HH (1981) Demonstration and characterization of opiate inhibition of the striatal adenylate cyclase. J Neurochem 36:1834–1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JJ, Mcllwrath SL, Woodbury CJ, Davis BM, Koerber HR (2008) TRPV1 unlike TRPV2 is restricted to a subset of mechanically insensitive cutaneous nociceptors responding to heat. J Pain 9:298–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bourdonnec B et al. (2009) Spirocyclic delta opioid receptor agonists for the treatment of pain: discovery of N,N-diethyl-3-hydroxy-4-(spiro[chromene-2,4’-piperidine]-4-yl) benzamide (ADL5747). J Med Chem 52:5685–5702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pichon CE, Chesler AT (2014) The functional and anatomical dissection of somatosensory subpopulations using mouse genetics. Front Neuroanat 8:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage F et al. (1995) Molecular properties of neuronal G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. J Biol Chem 270:28660–28667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin GR, Moshourab R (2004) Mechanosensation and pain. J Neurobiol 61:30–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L et al. (2011) The functional organization of cutaneous low-threshold mechanosensory neurons. Cell 147:1615–1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ma Q (2011) Generation of somatic sensory neuron diversity and implications on sensory coding. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21:52–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q et al. (2009) Sensory neuron-specific GPCR Mrgprs are itch receptors mediating chloroquine-induced pruritus. Cell 139:1353–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin EA, Bautista DM (2005) Feeling the pressure in mammalian somatosensation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15:382–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W et al. (2007) A hierarchical NGF signaling cascade controls ret-dependent and ret-independent events during development of nonpeptidergic DRG neurons. Neuron 54:739–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Enomoto H, Rice FL, Milbrandt J, Ginty DD (2009) Molecular identification of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors and their developmental dependence on ret signaling. Neuron 64:841–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q (2010) Labeled lines meet and talk: population coding of somatic sensations. J Clin Invest 120:3773–3778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makman MH, Dvorkin B, Crain SM (1988) Modulation of adenylate cyclase activity of mouse spinal cord-ganglion explants by opioids, serotonin and pertussis toxin. Brain Res 445:303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Khachaturian H, Lewis ME, Akil H, Watson SJ (1987) Autoradiographic differentiation of mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors in the rat forebrain and midbrain. J Neurosci 7:2445–2464 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark MD, Herlitze S (2000) G-protein mediated gating of inward-rectifier K+ channels. Eur J Biochem 267:5830–5836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennicken F et al. (2003) Phylogenetic changes in the expression of delta opioid receptors in spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol 465:349–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami M, Maekawa K, Yabuuchi K, Satoh M (1995) Double in-situ hybridization study on coexistence of mu-opioid, delta-opioid and kappa-opioid receptor messenger-rnas with preprotachykinin-a messenger-rna in the rat dorsal-root ganglia. Mol Brain Res 30:203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal N et al. (2013) Select G-protein-coupled receptors modulate agonist-induced signaling via a ROCK, LIMK, and beta-arrestin 1 pathway. Cell Rep 5:1010–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moises HC, Rusin KI, Macdonald RL (1994) Mu- and kappa-opioid receptors selectively reduce the same transient components of high-threshold calcium current in rat dorsal root ganglion sensory neurons. J Neurosci 14:5903–5916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momin A, Cadiou H, Mason A, McNaughton PA (2008) Role of the hyperpolarization-activated current Ih in somatosensory neurons. J Physiol 586:5911–5929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M et al. (2001) Distribution of various calcium channel alpha(1) subunits in murine DRG neurons and antinociceptive effect of omega-conotoxin SVIB in mice. Brain Res 903:231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali SS et al. (2015) High-voltage-activated calcium current subtypes in mouse DRG neurons adapt in a subpopulation-specific manner after nerve injury. J Neurophysiol 113:1511–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ (2004) Historical review: molecular and cellular mechanisms of opiate and cocaine addiction. Trends Pharmacol Sci 25:210–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nockemann D et al. (2013) The K(+) channel GIRK2 is both necessary and sufficient for peripheral opioid-mediated analgesia. EMBO Mol Med 5:1263–1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel J et al. (2009) The mechano-activated K+ channels TRAAK and TREK-1 control both warm and cold perception. EMBO J 28:1308–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normandin A, Luccarini P, Molat JL, Gendron L, Dallel R (2013) Spinal mu and delta opioids inhibit both thermal and mechanical pain in rats. J Neurosci 33:11703–11714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowycky MC, Fox AP, Tsien RW (1985) Three types of neuronal calcium channel with different calcium agonist sensitivity. Nature 316:440–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki C et al. (2012) Delta-opioid mechanisms for ADL5747 and ADL5859 effects in mice: analgesia, locomotion, and receptor internalization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 342:799–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara I et al. (2009) Local peripheral opioid effects and expression of opioid genes in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia in neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Pain 141:283–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocana M, Cendan CM, Cobos EJ, Entrena JM, Baeyens JM (2004) Potassium channels and pain: present realities and future opportunities. Eur J Pharmacol 500:203–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo T, Shibata M (1995) ATP-sensitive K+ channels mediate regulation of substance P release via the prejunctional histamine H3 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol 277:45–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olianas MC, Onali P (1995) Participation of delta opioid receptor subtypes in the stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity in rat olfactory bulb. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 275:1560–1567 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis V, Sarret P, Gendron L (2011) Spinal activation of delta opioid receptors alleviates cancer-related bone pain. Neuroscience 183:221–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overland AC et al. (2009) Protein kinase C mediates the synergistic interaction between agonists acting at alpha2-adrenergic and delta-opioid receptors in spinal cord. J Neurosci 29:13264–13273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco Dda F, Pacheco CM, Duarte ID (2012) Peripheral antinociception induced by delta-opioid receptors activation, but not mu- or kappa-, is mediated by Ca(2)(+)-activated cl(−) channels. Eur J Pharmacol 674:255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco DF, Duarte ID (2005) Delta-opioid receptor agonist SNC80 induces peripheral antinociception via activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Eur J Pharmacol 512:23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan HL et al. (2008) Modulation of pain transmission by G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther 117:141–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare M, Elde R, Mazurkiewicz JE, Smith AM, Rice FL (2001) The Meissner corpuscle revised: a multiafferented mechanoreceptor with nociceptor immunochemical properties. J Neurosci 21:7236–7246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan AM et al. (2006) PAR-2 agonists activate trigeminal nociceptors and induce functional competence in the delta opioid receptor. Pain 125:114–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peier AM et al. (2002) A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Cell 108:705–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]