Abstract

Two interesting plants within the Chilean flora (wild and crop species) can be found with a history related to modern fruticulture: Fragaria chiloensis subsp. chiloensis (Rosaceae) and Vasconcellea pubescens (Caricaceae). Both species have a wide natural distribution, which goes from the Andes mountains to the sea (East-West), and from the Atacama desert to the South of Chile (North-South). The growing locations are included within the Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forest hotspot. Global warming is of great concern as it increases the risk of losing wild plant species, but at the same time, gives a chance for usually longer term genetic improvement using naturally adapted material and the source for generating healthy foods. Modern agriculture intensifies the attractiveness of native undomesticated species as a way to provide compounds like antioxidants or tolerant plants for climate change scenario. F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis as the mother of commercial strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) is an interesting genetic source for the improvement of fruit flavor and stress tolerance. On the other hand, V. pubescens produces fruit with high level of antioxidants and proteolytic enzymes of interest to the food industry. The current review compiles the botanical, physiological and phytochemical description of F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis and V. pubescens, highlighting their potential as functional foods and as source of compounds with several applications in the pharmaceutical, biotechnological, and food science. The impact of global warming scenario on the distribution of the species is also discussed.

Keywords: Chilean strawberry, Fragaria chiloensis subsp. chiloensis, mountain papaya, new crops, Vasconcellea pubescens

Introduction

Few grain species were initially used in human diet. Several other vascular plants species have been incorporated and plant breeding effort have selected inbreeds with interesting and desirable characteristics focus on productivity (Khoshbakh and Hammer, 2008; Şerban et al., 2008). In the case of fruit species, characteristic like, fruit size, color, and texture have been the main quality attributes followed by breeders during the last century, but now a great interest for new traits, such as good aroma, pathogen resistance, high level of antioxidants, healthy compounds, and better postharvest life are considered. Nowadays, fruits from native species could be incorporated in our diet due to their contribution as functional food. In particular, strawberries are rich in secondary metabolites, as well as other attributes, however the fruit is susceptible to several diseases. Hancock et al. (2010) recognizes the importance of octoploid species such as F. chiloensis and F. virginiana to enrich traits such as resistance to diseases or better performance against biotic or abiotic stresses in new commercial lines of F. × ananassa. The global warming scenario of our planet has greatest importance in recent days, as the risk to lose wild plant species is certain due to changes in the ecological conditions (Feng et al., 2010; Lippmann et al., 2019; Moran, 2020). Chile is a world center of origin for cultivated plants and also considered as a biodiversity hotspot. In this sense, two interesting taxa with a history related to modern fruticulture can be mentioned: Fragaria chiloensis (L.) Mill. subsp. chiloensis (Rosaceae), known as the Chilean strawberry, and Vasconcellea pubescens A. DC. (Caricaceae), known as mountain papaya. The present article describes the development, use and potential future for both species.

Mountain Papaya

Vasconcellea pubescens A. DC. (Caricaceae) (synonyms: Carica pubescens Lenné & K. Koch, C. candamarcensis Hook. f., and V. cundinamarcensis V.M. Badillo) (Badillo, 2000; Van Droogenbroeck et al., 2002; Hassler, 2019), known as highland or mountain papaya, is a diploid dicotyledonous species (2n = 2x =18). It is native from subtropical Andean mountains of South America, in particular from low dry mountain forest areas in Colombia and Ecuador (2,000 to 3,000 m altitude). Ecuador, which has 15 of the 21 Vasconcellea species, is a center of genetic biodiversity (Van den Eynden et al., 1999; Scheldeman et al., 2011). Some genotypes of V. pubescens have been well adapted to central Chile before the Spanish colonization, suggesting that its introduction occurred during the Inca Empire or even earlier (Latcham, 1936). A surface of 180 ha of commercial orchards (ODEPA-CIREN, 2019), mostly located between 30° and 33° latitude south (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1), highlights Chile as the only country in the southern hemisphere producing the fruit at commercial scale and using it as a source of processed products.

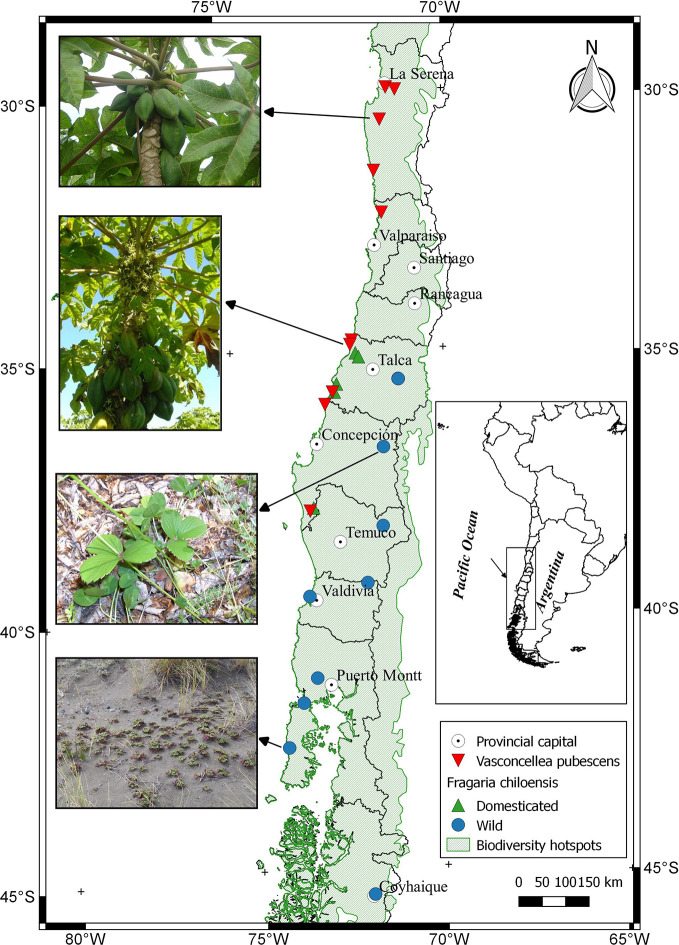

Figure 1.

Distribution of Fragaria chiloensis (wild and domesticated) and Vasconcellea pubescens in Chile. The map shows a partial extension (area) of the Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forests hotspot. Images located on the left side of the map, from North to South, corresponded to V. pubescens plants grown at the localities of Limarí and Lipimávida, and for F. chiloensis f. patagonica grown at Termas de Chillán and Cucao, respectively.

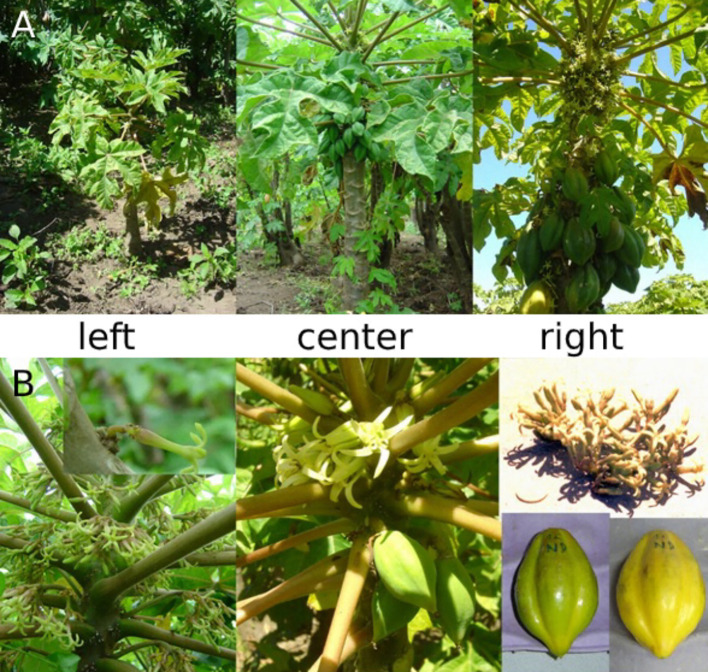

Mountain papaya is an arborescent plant reaching 1 to 8 m tall, with one central stem and palmate leaves with long petioles at the top (Figure 2A). Most of individual plants are dioecious, but a wide range of hermaphrodite phenotype is possible to identify in the field, so formally it is a sub-dioecious species with three sex phenotypes: female, male, and hermaphrodite (Figure 2B) (Badillo, 1993). V. pubescens presents a case of andromonoecious, where bisexuality is observed in male plants, with a high proportion of male flowers and hermaphrodite ones. Bisexual flowers are male flowers bearing viable ovules leading to the production of small fruits (Scheldeman et al., 2011). Sex in V. pubescens is determined by two factors, the Ypm chromosome and pm cytoplasmic factor (Horovitz and Jimenez, 1967), which are primitive sex chromosomes and a model for sex evolution determination (Na et al., 2014). The reproductive mode is through seeds, taking between 10 to 12 months to reach reproductive age, and maintained for 5 years at commercial scale. Then, plants progressively produce less fruit and with lower quality, nevertheless, plants older than 20 years are found in Chilean orchards. Mountain papaya tree shows a slow growth, with a continuous flower and leaf production; when lower leaves get older they fall into the ground (Sánchez, 1994).

Figure 2.

Morphological characteristics of V. pubescens tree, flowers and fruit. (A) Mountain papaya tree at three growing stages: a two month old tree of half a meter tall producing the first flowers (left); after one year, the tree reaches one meter tall and produces fruit (center); after three years, the tree is two meters tall, it is under full fruit production (right); interestingly, fruit at different developmental stages could be observed in the same tree. (B) Sexual forms in V. pubescens. Male plants produce staminate flowers, showing their characteristic elongated form, with the stamen inside the flower (left). Female plants produce pistillate flowers, with the characteristic enlargement of the flower base, because of ovary growth (center). Andromonoecious plants produce hermaphrodite and estaminate flowers, where the first ones differentiate from pistillate flowers showing a wider enlargement of flower base (up right). The most notorious change during fruit ripening is the color change of fruit skin, varying from an intense green to bright yellow color (down right).

V. pubescens is sensitive to cold, stem and leaves could be affected leading to complete plant death when temperatures fall below 2°C; even ripening of the fruit could be altered by cold. Cold episodes have been more frequent in Chile in recent years, even in coastal areas where chilling injuries on commercial orchards were absolutely absent 10 years ago. Additionally, extended drought stress promotes the continuous loss of leaves (Sánchez, 1994).

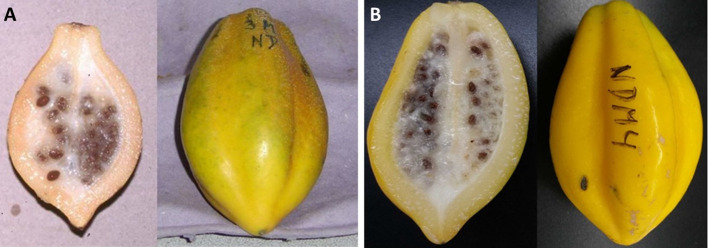

Mountain papaya tree bears fruit at the leaf axis spirally arranged along the trunk, so it is possible to observe from immature (small size, green colour) to ripe (big size, bright yellow) fruit stages in one single plant. In natural populations, birds eat ripe and overripe fruits, allowing seed dispersal and germination. Seeds have a high germination rate (60% in 30 days) without the requirement of a dormancy period (Sánchez, 1994). The fruit is oblong, truncated at the base, with five pronounced ridges; a ripe fruit is about 8–15 cm long, 5–6 cm diameter, and 200 g mean weight (García, 1975) (Figure 3). The fruit has a juicy yellow flesh with a strong and aromatic flavor, characterized by a high content of vitamins (A, B, and C), high level of antioxidants, and a milky latex (highly abundant in immature stages) that contains a mixture of proteolytic enzymes, commonly named as papain (Van Droogenbroeck et al., 2002; Moya-León et al., 2004). The fruit is commonly used to prepare preserves, jam, sweet candies and nectar, meanwhile its latex is widely used in the industry as meat tenderizer. Mountain papaya is frequently compared with the common and worldwide known papaya (Carica papaya L.), being V. pubescens smaller and less succulent than C. papaya but with a greater aroma and flavor (Van den Eynden et al., 1999; Scheldeman et al., 2003; Van den Eynden et al., 2003).

Figure 3.

Morphological characteristics of mountain papaya fruit at the ripe stage. Fruit shows its characteristic shape, thin pulp layer, with an inside cavity full of maternal tissue that contains many seeds (left), and the typical yellow skin color of ripe fruit with five ridges (right). The fruit was harvested at Lipimávida in seasons 2010 (A) and 2018 (B).

Diversity and Genetic Structure

Some phenotypic variations are observed in mountain papaya, mainly in plant height, number of branches and fruit size. Nevertheless, the most important differences are in sex determination. Although no environmental variation can be observed for pistillate and staminate plants, the proportion of male and hermaphrodite flowers in andromonoecious plants depends on climate conditions. On the other hand, the incompatibility barrier is labile in Vasconcellea, and therefore, this allows the possibility to increase genetic variation through the formation of spontaneous hybrid specimens between different species (Badillo, 1993; Sánchez, 1994). Interspecific hybrids have been found in natural populations (De Zerpa, 1959), however only one has commercial success: the babaco (Vasconcellea × heilbornii (V.M. Badillo) V.M. Badillo). Babaco results from the cross between V. pubescens and V. stipulata (V.M. Badillo) V.M. Badillo (Horovitz and Jimenez, 1967; Badillo, 1971; Scheldeman et al., 2011). Molecular studies using molecular markers suggest that the origin of V. × heilbornii results of a complex evolution process where V. pubescens, V. stipulata, and V. weberbaueri (Harms) V.M. Badillo are parental species (Scheldeman et al., 2011). Molecular analysis also confirms hybrids obtained by the cross of V. pubescens and V. monoica (Desf.) A. DC. (Kyndt et al., 2005; Kyndt et al., 2006) and interspecific crosses with V. stipulata, V. monoica, V. microcarpa (Jacq.) A. DC. and V. horovitziana (V.M. Badillo) V.M. Badillo (Horovitz and Jimenez, 1967; Badillo, 1971).

A high genetic diversity along the natural distribution pattern in the centres of origin (Ecuador and northern Perú) is assumed, but scarce information exists regarding the history and genetic diversity of V. pubescens introduced in Chile. A low genetic variability but a high genetic polymorphism was reported using ISSR markers (Carrasco et al., 2009). Based on the results, the authors suggested that few introduction events of genetic material from the original populations were concreted during time and this material constitutes the basal genotype of Chilean material.

Phytochemistry

Aroma is one of the most important attributes of mountain papaya fruit and it is due to a complex mixture of volatile compounds produced by the fruit (Balbontín et al., 2007). Main volatile compounds produced by the fruit are esters and alcohols (linear and branched), and their production increase as ripening progresses (Balbontín et al., 2007). Most of esters identified in mountain papaya fruit are potent odour compounds, such as ethyl butanoate, ethyl acetate, ethyl hexanoate, and ethyl 2-methylbutanoate, and the most important alcohol is butanol. The dynamic of their production during ripening depends on ethylene, which agrees to consider mountain papaya as a climacteric fruit (Moya-León et al., 2004; Balbontín et al., 2007). Several other volatile compounds such as methyl cis-hex-3-enoate, isopentyl acetate, methyl 3-hydroxyhexanoate and ethyl nicotinoate have been reported in mountain papaya fruit grown in Chile, however they have not been detected in fruit grown in Colombia (Morales and Duque, 1987). On the other hand, many fruits accumulate antioxidant activity during ripening, which is a desirable feature for functional foods. Active antioxidant phenolics from mountain papaya fruit include quercetin glycosides, rutin, and manghaslin, which are not produced by common papaya (C. papaya) (Simirgiotis et al., 2009). This suggests a metabolic divergence between both plant species.

All members of the Caricaceae family have laticifers and produce milky latex when a plant tissue is damaged. This latex helps as a defensive mechanism against predators and to heal wounded sites (Konno et al., 2004). The latex composition and proteinase quantity is different between species. The latex from C. papaya has been described and it consists of a mixture of hydrolase enzymes like quitinases and proteases, being the most characteristics papain, chymopapain, caricain (proteinase Ω) and glycil endopeptidase (proteinase IV) (El Moussaoui et al., 2001). There are some evidences showing that freeze-dried latex from V. pubescens has 5 to 8 times more proteolytic activity compare to the one obtained from C. papaya (Baeza et al., 1990). On the other hand, the extraction of V. pubescens latex and its separation into four different fractions named as CC-I to CC-IV was reported (Walraevens et al., 1993); two of them, CC-I and CC-III have been characterized and corresponded to papain and chymopapain, respectively. The mixture of latex proteinases has been used to treat gastric ulcers in rodent models (Mello et al., 2008). More recently, two different fractions were obtained from V. pubescens latex: a fraction showing high proteinase activity (CMS) and a fraction showing moderate to low proteinase activity (Teixeira et al., 2008). On the other hand, the fraction called P1G10 has been used for gastric ulcers and diabetic foot treatments in several wounded models (Tonaco et al., 2018). At the same time, the reduction of tumour mass in animals bearing melanoma and metastasis level was observed using this fraction (Lemos et al., 2018).

The Chilean Strawberry

Fragaria L. is a member of the Rosaceae family. There are about 20 species distributed in temperate Eurasia and North and South America. Staudt recognizes four subspecies for F. chiloensis (L.) Mill. based on morphological traits with a worldwide distribution: two of them are located in North America (F. chiloensis subsp. lucida (E.Vilm. ex J. Gay) Staudt, and F. chiloensis subsp. pacifica Staudt), one in Hawaii (F. chiloensis subsp. sandwicensis (Decne.) Staudt) and the last one in South-America (i.e., Ecuador, Bolivia, Perú, Argentina and Chile) (F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis Staudt) (Staudt, 1962; Bringhurst, 1990; Staudt, 1999). Staudt also proposed two botanical forms for the subspecies F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis based on characters such as plant size, texture of leaves, color and fruit size: F. chiloensis (L.) Mill. subsp. chiloensis f. chiloensis Staudt, is a landrace that produces large fruit with white/pink receptacle and white flesh; and F. chiloensis (L.) Mill. subsp. chiloensis f. patagonica Staudt, that produces small red fruits (Staudt, 1962; Staudt, 1999). Shortly after the conquest of the Central-South part of Chile, location where the Mapuches used to live, F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis was taken as a war trophy by the Spaniards and the species was introduced in Perú. Historical reports indicate that Garcilaso de la Vega in 1557 observed a new strawberry species in the land and markets of Cuzco City, different in size compared to the European species (Popenoe, 1921). Thereafter, the species was introduced in Ecuador by the Spaniards; although there are not exact records, it seems to be before 1789 (Popenoe, 1921). Interestingly, it was not until 1712 that F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis was introduced in Europe by some explorers coming from Chile (Popenoe, 1921; Darrow, 1966; Liston et al., 2014). From an agronomic perspective, mainly in Chile and in minor scale in Perú and Ecuador, F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis was cultivated as a fruit source during the first half of 1900 century, however when new cultivars reached from Europe and USA, the species was displaced and its cultivation was not favoured (Finn et al., 2013).

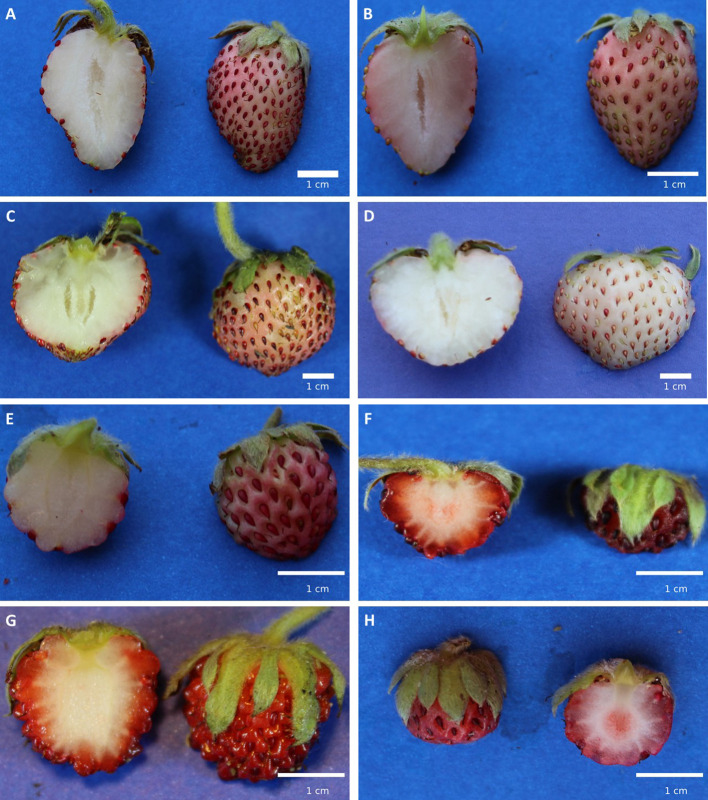

In botanical terms, F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis is a perennial herb, with strong and well developed runners; trifoliate leaves; with unique or few flowers, which can be dioic or hermaphrodite. The berry is an aggregate fruit, which develops from a flower that contains several ovaries (Marticorena, 2019). The fertilized ovaries develop into achenes that resulted embedded on surface of the receptacle. The edible receptacle or thalamus is usually considered as the most attractive part in sensory terms (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Morphological characteristics of Chilean strawberry fruit at the ripe stage. (A-D) correspond to Fragaria chiloensis f. chiloensis fruit distributed from North to South, from the localities of Huelón Alto, Pelluhue, Purén and Contulmo, respectively. (E-H) correspond to wild F. chiloensis fruit distributed from North to South, from the localities of Termas de Chillán (see Figure 1), Curiñanco, Cuesta Gutiérrez and Cucao (see Figure 1), respectively.

Nowadays in Chile, the two botanical forms of F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis grow in central-south part of Chile (Figure 1), and can be found between the O´Higgins and the Aysén Regions (35°05'– 45°32' latitude South) (Lavin et al., 2000; Rodríguez et al., 2018), growing from forests (understory) to open vegetation environments (Kalkman, 2004) (Figure 1). These areas present contrasting conditions for plant development, with differences in light, temperature and nutrients availability (Moreira-Muñoz, 2011). The fruit phenotype of Chilean accessions is quite diverse. As a way to demonstrate this, plants collected from different geographic areas were established in one edaphoclimatic condition (Linares) (Supplementary Table 1). Cultivated F. chiloensis f. chiloensis species from Huelón Alto, Pelluhue, Purén, and Contulmo produces fruit of white flesh, white/pink receptacle of uniform medium size (Figures 4A–D). On the contrary, the fruit produced by wild plants of F. chiloensis f. patagonica collected in Termas de Chillán, Curiñanco, Cuesta Gutiérrez and Cucao produce small fruit size with red receptacle (Figures 4E–H). The white flesh fruit is commercially produced at small scale and its main use is for fresh consuming or to prepare beverages (Pardo and Pizarro, 2013).

F. chiloensis f. chiloensis (white fruit) is considered as one of the parentals for the commercial strawberry (F. × ananassa (Duchesne ex Weston) Duchesne ex Rozier) along with F. virginiana Mill., which have also been supported by molecular analysis (Njuguna et al., 2013; Tennessen et al., 2014; Edger et al., 2019). F. chiloensis f. chiloensis has been widely studied particularly for its distinctive exotic white-pink color and characteristic aroma (Hancock et al., 1999; Retamales et al., 2005; González et al., 2009b). Several studies have been published reporting the softening of this fruit, showing that when firmness is reduced cell wall polymers are broken down (Figueroa et al., 2008; Moya-León et al., 2019). Several genes and enzymes involved in cell wall disassembly have been characterized (Figueroa et al., 2008; Figueroa et al., 2009; Pimentel et al., 2010; Opazo et al., 2013; Méndez-Yáñez et al., 2017; Méndez-Yáñez et al., 2020). Softening requires the fine coordination of several molecular activities, including the participation of plant hormones and transcription factors (Handford et al., 2014; Carrasco-Orellana et al., 2018; Moya-León et al., 2019). The key role played by the molecular coordinators on the expression of cell wall degrading genes impacts softening and the postharvest quality of the fruit.

The plant and fruit of F. chiloensis f. chiloensis show tolerance to pathogens and diseases (González et al., 2013). In addition, the plant species has the ability to grow under different abiotic stress conditions (low temperatures, salty soils) which gives a great potential for breeding purposes (González et al., 2009a; Aceituno-Valenzuela et al., 2018). In this sense, the species can be considered as genetic source for strawberry breeding programs.

F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis is located in one of the worldwide biodiversity hotspots. A hotspot is defined as an area with high diversity of endemic species (over 1,500), where 30% or less of this area should be threatened, and there are 34 areas recognized globally (Arroyo et al., 1999; Myers et al., 2000; Mittermeier et al., 2004). The Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forests hotspot covers a great part of northern and southern Chile and contains 1,957 different endemic species (Mittermeier et al., 2004). A reduction of plant communities have been observed directly by a high change in soil use from forests to forest plantations or agriculture (Arroyo et al., 1999). Several species belong to this area, which are used for human consumption (Table 1). Climate change models predict for the geographic area of this hotspot a decrease in the distribution range of plant species, in addition to, distribution displacements towards the south or to take refuge in the Andes Mountains (Pliscoff et al., 2012; Bambach et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Native plants from the Chilean winter rainfall-Valdivian forest hotspot with potential in agriculture.

| Native plants | Edible organ | Folk name | Family |

|---|---|---|---|

| Araucaria araucana (Molina) K. Koch | Fruit | Pehuen | Araucariaceae |

| Aristotelia chilensis (Molina) Stuntz | Fruit | Maqui | Elaeocarpaceae |

| Berberis microphylla G. Forst. | Fruit | Calafate | Berberidaceae |

| Eulychnia acida Phil. | Fruit | Copao | Cactaceae |

| Gaultheria species | Fruit | Chauras | Ericaceae |

| Geoffrea decorticans (Gillies ex Hook. et Arn.) Burkart | Fruit | Chañar | Fabaceae |

| Gevuina avellana Molina | Fruit | Avellano | Proteaceae |

| Gomortega keule (Molina) Baill. | Fruit | Queule | Gomortegaceae |

| Gunnera tinctoria (Molina) Mirb. | Petiole | Pangue | Gunneraceae |

| Lardizabala biternata Ruiz et Pav. | Fruit | Cóguil | Lardizabalaceae |

| Peumus boldus Molina | Fruit | Boldo | Monimiaceae |

| Prosopis chilensis (Molina) Stuntz emend. Burkart | Fruit | Algarrobo | Fabaceae |

| Prumnopitys andina (Poepp. ex Endl.) de Laub. | Fruit | Lleuque | Podocarpaceae |

| Puya chilensis Molina | Vegetative buds | Puya | Bromeliaceae |

| Ribes magellanicum Poir. | Fruit | Zarzaparrilla | Grossulariaceae |

| Rubus geoides Sm. | Fruit | Miñe miñe | Rosaceae |

| Solanum tuberosum L. subsp. tuberosum | Tuber | Papa chilota | Solanaceae |

| Ugni molinae Turcz. | Fruit | Murtilla | Myrtaceae |

Diversity and Genetic Structure

A center of diversity assures sustainable genetic improvement for plant species. The wide range of environmental conditions covered by the Chilean hotspot can be used as a source of genetic adaptation to different habitats, conferring tolerance to several stresses or environmental factors. Besides, the loss of genetic diversity within a species can result in the loss of useful and desirable traits and may eliminate options to use untapped resources for food production, industry and medicine (Hoisington et al., 1999; Govindaraj et al., 2015).

The genetic diversity in Fragaria has been studied using molecular markers such as microsatellites (SSR) or dominant markers (ISSR, AFLP and RAPD), and more recently using a high throughput system such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) array (Bassil et al., 2015; Hilmarsson et al., 2017; Jung et al., 2017). SSR markers, for example, were used with the purpose to identify F. × ananassa cultivars (Monfort et al., 2006; Shimomura and Hirashima, 2006; Honjo et al., 2011). The IStraw90 Axiom array is a genotyping platform for Fragaria able to identify SNPs, indels, and also is used for mapping (Mahoney et al., 2016; Nagano et al., 2017; Sooriyapathirana et al., 2019; Oh et al., 2020). In the case of F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis a small number of accessions were analyzed and low genetic diversity and no genetic structure was reported (Carrasco et al., 2007; Oñate et al., 2018). The vegetative propagation of the species was used as argument for the low genetic variability found along Chile (Lavin et al., 2000), however despite of that, a breeding and improvement program on the species was considered feasible. Several crosses of the Chilean strawberry and Fragaria spp have been performed which have been evaluated for the generation of elite genotypes (Hancock et al., 2001; Finn et al., 2013). Recently, new hybrids were successfully obtained by crossing four different F. × ananassa cultivars with F. chiloensis f chiloensis, increasing diversity and facilitating new bridge species for breeding (Luque et al., 2019). The selection from the breeding programe can be facilitated and optimized by the use of molecular techniques (Edger et al., 2019; Oh et al., 2019).

Phytochemistry

F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis fruit contains an interesting composition of phenolics and high antioxidant activity. Ellagic acid and cinnamic acid glycosides are present in the white Chilean strawberry fruit (Cheel et al., 2005), and the fruit is also rich in phenolic antioxidants (Cheel et al., 2007; Simirgiotis et al., 2009). In addition, the fruit is characterized for having great aroma properties (González et al., 2009b). Differences in the volatile profiles have been described among commercial strawberry cultivars (Staudt et al., 1975; Forney et al., 2000), and most importantly between cultivated and wild species, being wild species those with the highest concentration of volatiles and better aroma properties (Ulrich et al., 2007). Commercial strawberries produce numerous volatile compounds including esters, aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, terpenes, furanones, and sulfur compounds (Latrasse, 1991; Zabetakis and Holden, 1997), nevertheless esters are the most abundant class of compounds (25% to 90% of total volatiles) (Pérez et al., 1992), and provide the fruity notes of fresh ripe fruit (Pyysalo et al., 1979; Schreier, 1980). Some esters identified in the white Chilean strawberry fruit include ethyl acetate, methyl butanoate, 2-methyl acetate, octyl acetate, octyl butanoate, hexyl acetate, ethyl heptanoate, 2-hexenyl butanoate, benzyl acetate, and hexyl 2-methyl butanoate, which were also described in several F. × ananassa cultivars (Pyysalo et al., 1979; Zabetakis and Holden, 1997; Azodanlou et al., 2003; Berna et al., 2007; González et al., 2009b). Importantly, esters such as hexyl propanoate, ethyl 4-decenoate, 2-phenylethyl propanoate, and ethyl 2,4 decadienoate have been identified in F. chiloensis f. chiloensis and not in F. × ananassa (González et al., 2009b).

Anthocyanins are the color pigments of strawberry fruit. In red strawberries glycosylated anthocyanins derived from pelargonidin and cyanidin are normally present, being pelargonidin 3-glucoside the most abundant anthocyanin (Tulipani et al., 2008). In the white Chilean strawberry, the main anthocyanin is cyanidin 3-O-glucoside, which is mainly present in the achenes (Cheel et al., 2005; Salvatierra et al., 2010; Salvatierra et al., 2014). Importantly, anthocyanins have potential benefits and broad health-promoting effects for human considering the antioxidant activity (Chamorro et al., 2019; Hwang et al., 2019; Mazzoni et al., 2019).

The potential health benefits of strawberry fruit consumption have been analyzed, and some in vivo effects on the oxidative status in human and animal models are now available. Chilean white fruit aqueous extracts have a protective effect on platelet aggregation (Parra-Palma et al., 2018) and can exert protection on human epithelial gastric cells against free radical-induced damage (Avila et al., 2017). On the other hand, dietary supplementation of rats with white Chilean strawberry juice favors the normalization of oxidative and inflammatory effects in response to a liver injury induced by lipopolysaccharides (Molinett et al., 2015). These results support the idea to considerate the Chilean strawberry fruit as a functional food.

Mediterranean Crop and Climate Change

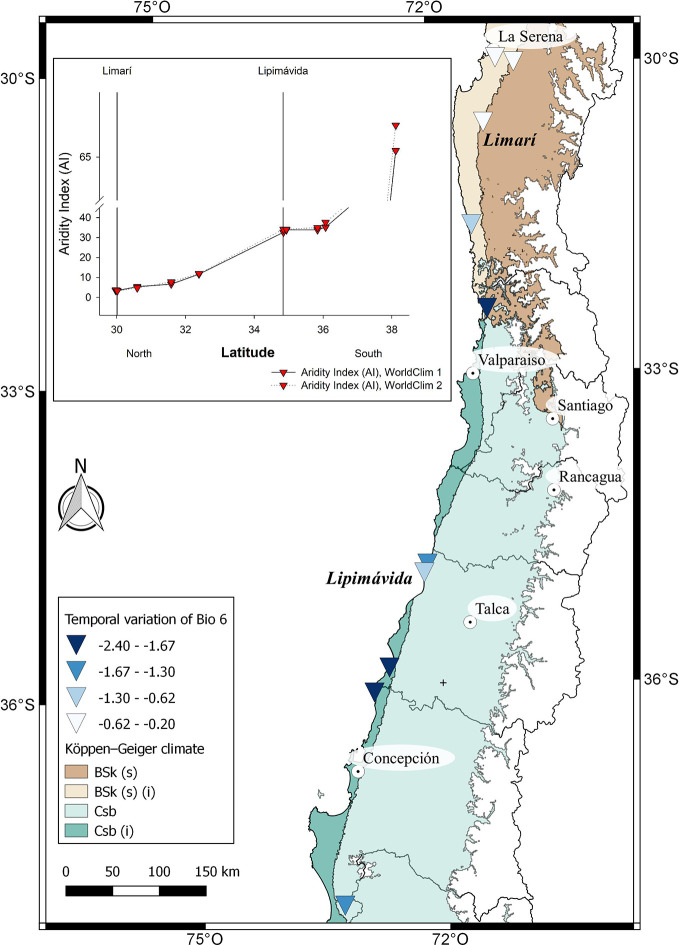

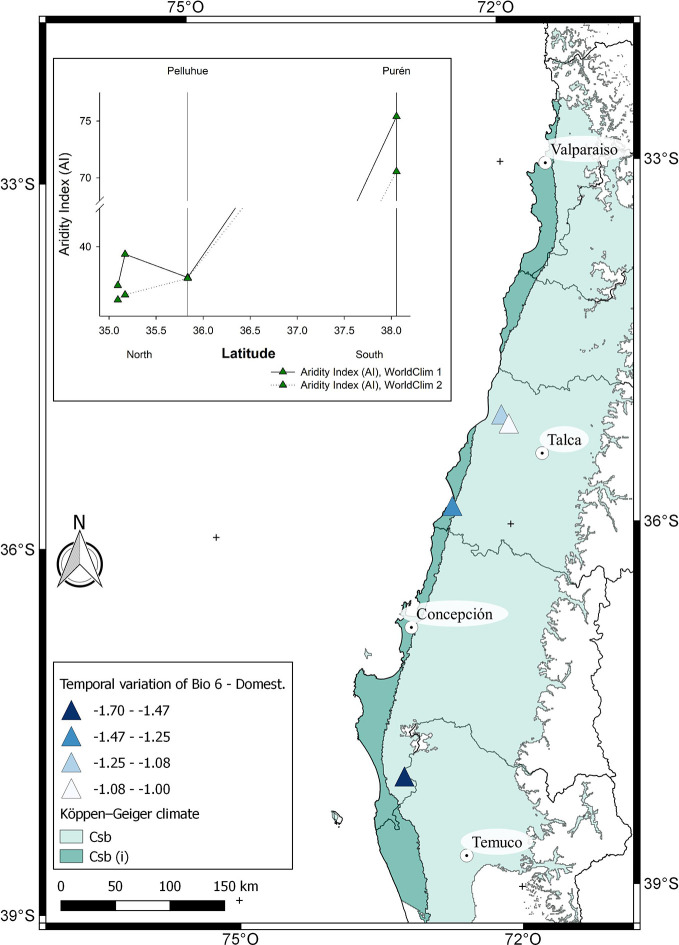

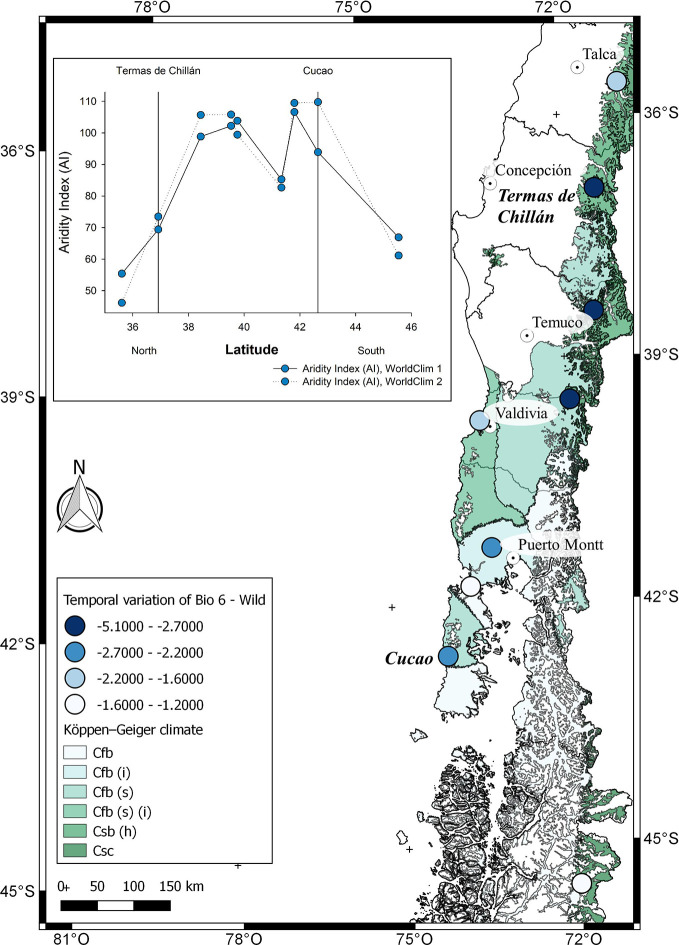

In general, papaya plants grow mostly in tropical and subtropical Andes. In Chile, as shown in Figure 1, mountain papaya (V. pubescens) is cultivated in coastal areas between latitudes 30° to 36° South, which corresponds to a climate with subtropical influence characterized by moderate thermal ranges and low occurrences of frosts. Recently, Sarricolea et al. (2017) carried out a climatic classification of Chile, and proposed that the cultivated populations of V. pubescens could be cultivated in 4 climatic types of Köppen-Geiger (see Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, regarding the cultivation of strawberry in Chile, both F. × ananassa and F. chiloensis f. chiloensis grow between latitudes 32° to 37° South, in coastal areas of Chile, where climate corresponds to a Mediterranean type, with 8 variants according to Köppen-Geiger climate classification (see Figures 6 and 7 and Supplementary Table 1, Sarricolea et al., 2017).

Figure 5.

Climatic characterization of cultivated localities of V. pubescens distributed from North to South. The comparison of Bioclimatic variable 6 (Min temperature of coldest month) between WorldClim 1 and 2 for each locality is shown in the map. In the insert, De Martonne Aridity Index (AI) for each locality. On the X axis, the localities of Limarí and Lipimávida are marked as reference, as previously shown in Figure 1.

Figure 6.

Climatic characterization of the localities where F. chiloensis f. chiloensis is cultivated in Chile and distributed from North to South. The comparison of Bioclimatic variable 6 (Min temperature of coldest month) between WorldClim 1 and 2 for each location is shown in the map. In the insert, De Martonne Aridity Index (AI) for each locality.

Figure 7.

Climatic characterization of the localities where F. chiloensis f. patagonica is distributed in Chile, from North to South. The comparison of Bioclimatic variable 6 (Min temperature of coldest month) between WorldClim 1 and 2 for each locality in which F. chiloensis f. patagonica grows are shown in the map. In the insert, De Martonne Aridity Index (AI) for each locality. On the X axis, the localities of Termas de Chillán and Cucao are marked as reference, as previously shown in Figure 1.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that mid-latitude areas would be affected by the increment in drought, with irregular rainfall regimes and rising temperatures (Parajuli et al., 2019). These locations are the cultivation areas where main crops are worldwide concentrated, which also include our both species under study. The average temperature and precipitation within the area of cultivation for V. pubescens and F. chiloensis can be estimated using the information provided by climate models such as WorldClim. WorldClim 1 considers the interpolation of observed climatic data representative for the period of 1960–1990 (Hijmans et al., 2005), and WorldClim 2 considers climatic data between 1970-2000 (Fick and Hijmans, 2017). Although WorldClim defines 19 bioclimatic variables, only Annual Mean Temperature (BIO 1), Min Temperature of Coldest Month (BIO 6) and Annual Precipitation (BIO 12) were used in this analysis as they provide robust differences between sites. Aridity index (AI) was determined using BIO1 and BIO12, which correlates the precipitation (annual or monthly) with mean temperature (also annual or monthly), and allows the classification of study sites as desert, meadow or forest (Wang and Takahashi, 1999). High aridity index values indicate a site with more water availability. Considering that the increase in frosts could affect crops in mid-latitude areas BIO 6 variable was also considered (Parajuli et al., 2019).

In the case of V. pubescens´s distribution, the model predict a similar precipitation behavior for each location along the years, with values from North to South ranging from 90 mm average in Limarí to 1,515 mm average at the southern end of the distribution (Lleu-Lleu) (Supplementary Figure 1). Interestingly, Squeo et al. (1999) indicated that the annual rainfall for the area of La Serena (north of Limarí) was reduced from 180 mm at the beginning of 1900 to about 80 mm by the year 2000, which evidences a precipitation drop of 40% during the last century. On the other hand, a slight decrease in the average annual temperature (BIO1) and a drop in the minimum temperature for the coldest month by at least 2.4 °C can be observed (Figure 5, Supplementary Figure 1); this drop is mainly observed in southern locations. Finally, no differences in aridity index are observed between the data provided by WorldClim 1 and WorldClim 2 for mountain papaya locations (Figure 5, insert).

The climatic behavior for growing locations of domesticated F. chiloensis f. chiloensis is shown in Supplementary Figure 2. Average annual temperature (BIO1) for the locations are the same in both models; however there is a reduction of about 1.7°C in the minimum temperature of the coldest month (BIO6) in WorldClim 2 compared to WorldClim1 (Figure 6). On the other hand, a dramatic reduction in rainfall is observed in southern locations (Purén) (around 100 mm) in WorldClim 2 compared to WorldClim 1 (Supplementary Figure 2). In general terms, there is a reduction in aridity index especially in the southern locations of domesticated strawberry (Figure 6, insert), which is also accompanied with a reduction in minimum temperatures during winter. As suggested by Bambach et al. (2013) these climate changes could affect the current distribution of the species.

Finally, the analysis of climate change for the locations of F. chiloensis f. patagonica is shown in Supplementary Figure 3. It is more complex to interpret as there is a latitudinal effect (North – South distribution of the localities) in addition to a longitudinal component (ie, East – West; mountain - seaside). Therefore, we will focus the comparison between the localities of Termas de Chillán and Cucao (Figures 1 and 7). Populations distributed between 36–40° South are located in the Andes mountain (nearby Termas de Chillán), meanwhile those distributed further south (42–46° South) are located at sea level (close to Cucao) (Supplementary Figure 3). A significant reduction in the minimum temperature of the coldest month of 4.2°C has been reported for Termas de Chillán location in WorldClim 2 compared to WorldClim 1 (Figure 7); a smaller reduction in minimum temperature was reported for Cucao (2.4°C) (Supplementary Figure 3). On the other hand, there are no significant differences in the average annual temperature for both locations, neither in the annual precipitation in Termas de Chillán (Supplementary Figure 3); nevertheless an increase of about 230 mm is reported in Cucao comparing WorldClim 2 and WorldClim 1. In terms of aridity index, there is a significant increment of around sixteen points for the location of Cucao in WorldClim 2 compared to WorldClim 1; a smaller increment in aridity index (4 points) was also observed in Termas de Chillán (Figure 7, insert). The particular climate properties of the Andes Mountains (high precipitation level, lower annual average temperature) could constitute a good refuge for this wild species, restricting current distributions to these areas (Bambach et al., 2013; Alarcón and Cavieres, 2015). In the case of cultivated species, the Andes Mountains can also constitute a refuge for the species, but its displacement to southern regions could be dedicated for agriculture development (Parajuli et al., 2019).

Crop Potential

Vasconcellea species has an interesting potential as a new crop, considering potential breeding for fruit and other sub-products and its domestication in specific geographic areas (Scheldeman et al., 2011). The two most important species are the babaco (Vasconcellea x heilbornii) in Ecuador and Colombia, and mountain papaya (Vasconcellea pubescens), in all Andean countries and particularly important at small commercial scale in Colombia (Scheldeman et al., 2011) and Chile (Moya-León et al., 2004). Interestingly, the cultivated surface of mountain papaya almost disappears after the earthquake and Tsunami of 2010 in the Maule Region, mainly because natural growing areas of the species were salinized and damaged by seawater. In the Maule Region, toxic levels of salty soil inhibit the growth of V. pubescens plants, because the content of salt reduces water availability to plants. In addition, the reduction in soil pH in depth (1.4 units) and surface (0.7 units) resulted as consequence of the ionic strength generated and the coarse-textured soil (Casanova et al., 2016). Remarkably, an increase in the cultivated surface of this species has been recently observed in the northern extreme of Chile (Arica and Parinacota Region, ~ 18° 30' latitude South), where 13.6 ha were recorded that represents 9% of total cultivated surface for the species in Chile (ODEPA-CIREN, 2019).

F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis has also potential as a new crop. Firstly, the production of phytochemicals with health benefits highlights the opportunity to use the species as a functional food. Secondly, the species has great resistance to several diseases (Rojas et al., 2013). Although Aphidborne virus (ABVs) has been detected in F. chiloensis subsp. chiloensis plants non visual symptoms of disease were determined, albeit the virus affects severely F. vesca plants. Similarly, F. chiloensis f chiloensis shows tolerance to Botrytis cinerea, a severe fungal disease which affects dramatically several fruit species (González et al., 2013). Also, it was reported that the Chilean strawberry presented higher tolerance to the fungus compared to F. × ananassa.

Ploidy and hybridization are the basis of current cultivated crops. Importantly, wild relatives have impacted positively the availability of crops, allowing the expansion of cultivation areas or increasing the tolerance to pest and diseases. In a climate change scenario, a breeding program is needed in order to obtain smart cultivars that can face the new challenges as a way to ensure sustainable production in the future (Borrell et al., 2020). Fruit homogeneity and other phenotypic characters have been the main effort of plant breeders, but new characteristic must be incorporated in modern crops, such as, tolerance to cold and high temperature environment, tolerance to drought or salinity and disease resistance (Doebley et al., 2006). May be taking into account the genetic variability of native species for those traits and using strategies like introgression or hybridization, the genetic improvement of these valuable crops can be possible.

Genomic selection has aided marker assisted selection to gain time during crop improvement (Heffner et al., 2010). Moreover, the incorporation of new tools for molecular breeding, such as genome sequencing, SNPs, or genome editing, facilitates the identification of new inbreeds; this strategy has been defined as design breeding (Heffner et al., 2011; Fernie and Yan, 2019).

Domestication of non-domesticated plants is a great opportunity to obtain cultivars well adapted to different edaphoclimatic niches. The long period of time required for selection from breeding programs can be accelerated by the use of a biotechnology approach and new genome editing techniques (Osterberg et al., 2017; Scheben et al., 2017; Wallace et al., 2018). Clearly, under the climate change scenario new type of cultivars are needed. The better adaptability to a variety of climatic conditions is a priority in current time as a way to reduce the negative impact of less food production in vulnerable environments.

Polyploidy can be a challenge for Chilean strawberry, but combining the information from genetic maps, the functional characterization of specific genes, and genome sequencing should be the starting point for applying this modern strategy (Rousseau-Gueutin et al., 2008; Davik et al., 2015; Vining et al., 2017; Edger et al., 2019; Moya-León et al., 2019). In the case of Vasconcellea pubescens there is no genomic or functional genomic data available until now, which can limit the breeding effort. However, wild plants are already adapted to a wide range of climatic conditions, considering their native habitat at high altitude of the Andes mountains. Chilean papaya is attractive as functional food and source of natural sub-products as papain proteases which can be the target for molecular breeding. For certain, the implementation of what is called breeding 4.0 or “de novo domestication” should provide new well adapted smart cultivars.

Author Contributions

The present work was conceived and designed by RH, CG-E, LL, PP, and MM-L. LL and CG-E contributed collecting information and preparing figures. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by FONDECYT grant 1171530. The funders had no part in the design of the study or collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, neither in writing the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.01002/full#supplementary-material

References

- Şerban P., Wilson J. R. U., Vamosi J. C., Richardson D. M. (2008). Plant diversity in the human diet: Weak phylogenetic signal indicates breadth. BioScience 58, 151–159. 10.1641/b580209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aceituno-Valenzuela U., Covarrubias M. P., Aguayo M. F., Valenzuela-Riffo F., Espinoza A., Gaete-Eastman C., et al. (2018). Identification of a type II cystatin in Fragaria chiloensis: a proteinase inhibitor differentially regulated during achene development and in response to biotic stress-related stimuli. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 129, 158–167. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón D., Cavieres L. A. (2015). In the right place at the right time: Habitat representation in protected areas of south american Nothofagus-dominated plants after a dispersal constrained climate change scenario. PloS One 10 (3), e0119952. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo M. T. K., Rozzi R., Simonetti J. A., Marquet P., Salaberry M. (1999). “Central Chile,” in Hotspots: Earth"s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecosystems. Eds. Mittermeier R. A., Myers N., Robles Gil P., Goettsch Mittermeier C. (México, México: Cemex, Conservation International; ), 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Avila F., Theoduloz C., López-Alarcón C., Dorta E., Schmeda-Hirschmann G. (2017). Cytoprotective mechanisms mediated by polyphenols from Chilean native berries against free radical-induced damage on AGS cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017 (1). 10.1155/2017/9808520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azodanlou R., Darbellay C., Luisier J. L., Villettaz J. C., Amado R. (2003). Quality assessment of strawberries (Fragaria species). J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 715–721. 10.1021/jf0200467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badillo V. M. (1971). Monografia de la familia Caricaceae (Maracay, Venezuela: Associación de Profesores, Univ. Cent. Venezuela; ). [Google Scholar]

- Badillo V. M. (1993). Caricaceae. Segundo esquema (Maracay, Venezuela: Rev. Fac. Agron. Univ. Cent. Venezuela, Alcance 43; ). [Google Scholar]

- Badillo V. M. (2000). Carica L. vs Vasconcella St. Hil. (Caricaceae): con la rehabilitación de este último. Ernstia 10, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Baeza G., Correa D., Salas C. (1990). Proteolytic enzymes in Carica candamarcensis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 51, 1–9. 10.1002/jsfa.2740510102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balbontín C., Gaete-Eastman C., Vergara M., Herrera R., Moya-León M. A. (2007). Treatment with 1-MCP and the role of ethylene in aroma development of mountain papaya fruit. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 43, 67–77. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bambach N., Meza F. J., Gilabert H., Miranda M. (2013). Impacts of climate change on the distribution of species and communities in the Chilean Mediterranean ecosystem. Reg. Environ. Change 13, 1245–1257. 10.1007/s10113-013-0425-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bassil N. V., Davis T. M., Alperin E., Amaya I., Bellon F., Brew F., et al. (2015). Development and preliminary evaluation of a 90K Axiom SNP array in the allo-octoploid cultivated strawberry Fragaria × ananassa. BMC Genomics 16, 155. 10.1186/s12864-015-1310-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berna A. Z., Geysen S., Li S., Verlinden B., Lammertyn J., Nicolai B. (2007). Headspace fingerprint mass spectrometry to characterize strawberry aroma at super-atmospheric oxygen conditions. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 46, 230–236. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.05.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell J. S., Dodsworth S., Forest F., Pérez-Escobar O. A., Lee M. A., Mattana E., et al. (2020). The climatic challenge: Which plants will people use in the next century? Environ. Exp. Bot. 170, 103872. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.103872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bringhurst R. S. (1990). Cytogenetics and evolution in american Fragaria. HortScience 25, 879–881. 10.21273/HORTSCI.25.8.879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco B., Garcés M., Rojas P., Saud G., Herrera R., Retamales J. B., et al. (2007). The Chilean strawberry [Fragaria chiloensis (L.) Duch.]: Genetic diversity and structure. J. Amer. Soc Hortic. Sci. 132, 501–506. 10.21273/JASHS.132.4.501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco B., Avila P., Pérez-Diaz J., Muñoz P., Garcia R., Lavandero B., et al. (2009). Genetic structure of highland papayas (Vasconcellea pubescens (A. DC.) Badillo) cultivated along a geographic gradient in Chile as revealed by inter simple sequence repeats (ISSR). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 56, 331–337. 10.1007/s10722-008-9367-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Orellana C., Stappung J., Méndez-Yañez A., Allan A., Espley R., Plunkett B., et al. (2018). Characterization of a ripening related transcription factor FcNAC1 from Fragaria chiloensis fruits. Sci. Rep. 8, 10524. 10.1038/s41598-018-28226-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova M., Salazar O., Oyarzun I., Tapia Y., Fajardo M. (2016). Field monitoring of 2010-tsunami impact on agricultural soils and irrigation waters: Central Chile. Water Air Soil Pollut. 227, 411. 10.1007/s11270-016-3113-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro M., Reiner G., Theoduluz C., Ladio A., Schmeda-Hirschmann G., Gomez-Alonso S., et al. (2019). Polyphenol composition and (Bio)activity of Berberis species and wild strawberry from the Argentinean patagonia. Molecules 24, 3331. 10.3390/moleculaes24183331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheel J., Theoduloz C., Rodríguez J., Saud G., Caligari P. D. S., Schmeda-Hirschmann G. (2005). E-Cinnamic acid derivatives and phenolics from chilean strawberry fruits, Fragaria chiloensis ssp. chiloensis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53 (22), 8512–8518. 10.1021/jf051294g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheel J., Theoduloz C., Rodriguez J. A., Caligari P. D. S., Schmeda-Hirschmann G. (2007). Free radical scavenging activity and phenolic content in achenes and thalamus from Fragaria chiloensis ssp. chiloensis, F. vesca and F. × ananassa cv. Chandler. Food Chem. 102, 36–44. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.04.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darrow G. W. (1966). The strawberry: History, breeding and physiology (New York, USA: Holf, Rinehart and Winston; ). [Google Scholar]

- Davik J., Sargent D., Brurberg M., Lien S., Kent M., Alsheikh M. (2015). A ddRAD based linkage map of the cultivated strawberry, Fragaria x ananassa. PloS One 10, e0137746. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Zerpa D. M. (1959). Citologia de hibridos interespecificos en Carica. Agron. Trop. (Maracay) 8, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Doebley J., Gaut B., Smith B. (2006). The molecular genetics of crop domestication. Cell 127, 1309–1321. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edger P. P., Poorten T. J., VanBuren R., Hardigan M. A., Colle M., McKain M. R., et al. (2019). Origin and evolution of the octoploid strawberry genome. Nat. Genet. 51, 541–547. 10.1038/s41588-019-0356-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Moussaoui A., Nijs M., Paul C., Wintjens R., Vincentelli J., Azarkan M., et al. (2001). Revisiting the enzymes stored in the laticifers of Carica papaya in the context of their possible participation in the plant defence mechanism. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 58, 556–570. 10.1007/PL00000881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Krueger A. B., Oppenheimer M. (2010). Linkages among climate change, crop yields and Mexico-US cross-border migration. PNAS 107, 14257–14262. 10.1073/pnas.1002632107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernie A., Yan J. (2019). De Novo Domestication: An Alternative Route toward New Crops for the Future. Mol. Plant 12, 615–631. 10.1016/j.molp.2019.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick S. E., Hijmans R. J. (2017). WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315. 10.1002/joc.5086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa C. R., Pimentel P., Gaete-Eastman C., Moya M., Herrera R., Caligari P. D. S., et al. (2008). Softening rate of the Chilean strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis) fruit reflects the expression of polygalacturonase and pectate lyase genes. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 49, 210–220. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.01.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa C. R., Pimentel P., Dotto M. C., Civello P. M., Martínez G. A., Herrera R., et al. (2009). Expression of five expansin genes during softening of Fragaria chiloensis fruit. Effect of auxin treatment. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 53, 51–57. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2009.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finn C., Retamales J., Lobos G., Hancock J. (2013). The Chilean strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis): over 1000 years of domestication. HortScience 48, 418–421. 10.21273/HORTSCI.48.4.418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forney C. F., Kalt W., Jordan M. A. (2000). The composition of strawberry aroma is influenced by cultivar, maturity and storage. HortScience 35, 1022–1026. 10.21273/HORTSCI.35.6.1022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García B. H. (1975). Flora medicinal de Colombia (Bogotá, Colombia: Imprenta Nacional; ). [Google Scholar]

- González G., Moya M., Sandoval C., Herrera R. (2009. a). Genetic diversity in Chilean strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis): differential response to Botrytis cinerea infection. Span. J. Agric. Res. 7, 886–895. 10.5424/sjar/2009074-1102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González M., Gaete-Eastman C., Valdenegro M., Figueroa C. R., Fuentes L., Herrera R., et al. (2009. b). Aroma development during ripening of F. chiloensis fruit and participation of an alcohol acyltransferase (FcAAT1) gene. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 9123–9132. 10.1021/jf901693j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González G., Fuentes L., Moya-León M. A., Sandoval C., Herrera R. (2013). Characterization of two PR genes from Fragaria chiloensis in response to Botrytis cinerea infection: A comparison with Fragaria × ananassa. Physiol. Mol. Plant P. 82, 73–80. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2013.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaraj M., Vetriventhan M., Srinivasan M. (2015). Importance of genetic diversity assessment in crop plants and its recent advances: An overview of its analytical perspectives. Genet. Res. Inter. 2015, 431487. 10.1155/2015/431487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J. F., Lavin A., Retamales J. B. (1999). Our sourthern strawberry heritage: Fragaria chiloensis of Chile. HortScience 34, 814–816. 10.21273/HORTSCI.34.5.814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J. F., Callow P. W., Dale A., Luby J. J., Finn C. E., Hokanson S., et al. (2001). From the Andes to the rockies: Native strawberry collection and utilization. Hortscience 36, 221–225. 10.21273/HORTSCI.36.2.221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J. F., Finn C. E., Luby J. J., Dale A., Callow P. W., Serçe S. (2010). Reconstruction of the strawberry, Fragaria × ananassa, using genotypes of F. virginiana and F. chiloensis. HortScience 45, 1006–1013. 10.21273/HORTSCI.45.7.1006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Handford M., Espinoza A., Bracamonte M., Figueroa A., Zapata S., Aceituno U., et al. (2014). Identification and characterization of key genes involved in fruit ripening of the Chilean strawberry. New Biotechnol. 31, S182–S182. 10.1016/j.nbt.2014.05.912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassler M. (2019). “World plants: Synonymic checklists of the vascular plants of the world (version Nov 2018),” in Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life, 2019 Annual Checklist. Eds. Roskov Y., Ower G., Orrell T., Nicolson D., Bailly N., Kirk P. M., Bourgoin T., DeWalt R. E., Decock W., Nieukerken E., van, Zarucchi J., (Netherlands: Naturalis Biodiversity Center), Penev L. Digital resource at www.catalogueoflife.org/annual-checklist/2019. Species 2000: Naturalis, Leiden, the Netherlands. ISSN 2405-884X.

- Heffner E. L., Lorenz A. J., Jannink J. L., Sorrells M. E. (2010). Plant breeding with genomic selection: gain per unit time and cost. Crop Sci. 50, 1681–1690. 10.2135/cropsci2009.11.0662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner E. L., Jannink J., Iwata H., Souza E., Sorrells M. E. (2011). Genomic selection accuracy for grain quality traits in biparental wheat population. Crop Sci. 51, 2597–2606. 10.2135/cropsci2011.05.0253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans R. J., Cameron S. E., Parra J. L., Jones P. G., Jarvis A. (2005). Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978. 10.1002/joc.1276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilmarsson H., Hytonen T., Isobe S., Goransson M., Toivanen T., Hallsson J. (2017). Population genetic analysis of a global collection of Fragaria vesca using microsatellite markers. PloS One 12, 8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0183384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoisington D., Khairallah M., Reeves T., Ribaut J. M., Skovmand B., Taba S., et al. (1999). Plant genetic resources: What can they contribute toward increasd crop productivity? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 5937–5943. 10.1073/pnas.96.11.5937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo M., Nunome T., Kataoka S., Yano T., Yamazaki H., Hamano M., et al. (2011). Strawberry cultivar identification based on hypervariable SSR markers. Breed. Sci. 61, 420–425. 10.1270/jsbbs.61.420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horovitz S., Jimenez H. (1967). Cruzamientos interespecíficos e intergenéricos en Caricaceas y sus implicaciones fitotécnicas. Agron. Trop. (Maracay) 17, 323–343. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H., Kim Y. J., Shin Y. (2019). Influence of ripening stage and cultivar on physicochemical propierties, sugar and organic acid profiles, and antioxidant compositions of strawberries. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 28, 1659–1667. 10.1007/s10068-019-00610-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H., Veerappan K., Natarajan S., Jeong N., Hwang I., Nagano S., et al. (2017). A system for distinguishing octoploid strawberry cultivars using high-throuput SNP genotyping. Trop. Plant Biol. 10, 68–76. 10.1007/s12042-017-9185-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkman C. (2004). “Rosaceae,” in The families and genera of vascular plants: Flowering plants dicotyledons. Ed. Kubitzki K. (Berlin, Deutschland: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; ), 343–386. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshbakh K., Hammer K. (2008). How many plant species are cultivated? Gen. Resour. Crop Evol. 55, 925–928. 10.1007/s10722-008-9368-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Konno K., Hirayama C., Nakamura M., Tateishi K., Tamura Y., Hattori M., et al. (2004). Papain protects papaya trees from herbivorous insects: role of cysteine proteases in latex. Plant J. 37, 370–378. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01968.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyndt T., Romeijn-Peeters E., Van Droogenbroeck B., Romero-Motochi J. P., Gheysen G., Goetghebeur P. (2005). Species relationships in the genus Vasconcellea (Caricaceae) based on molecular and morphological evidence. Am. J. Bot. 92, 1033–1044. 10.3732/ajb.92.6.1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyndt T., Van Droogenbroeck B., Haegeman A., Roldán-Ruiz I., Gheysen G. (2006). Cross-species microsatellite amplification in Vasconcellea and related genera and their use in germplasm classification. Genome 49, 786–798. 10.1139/g06-035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latcham R. (1936). La agricultura precolombina en Chile y en los países vecinos (Santiago, Chile: Ediciones de la Universidad de Chile; ). [Google Scholar]

- Latrasse A. (1991). “Fruits III,” in Volatile compounds in foods and beverages. Ed. Maarse H. (New York, USA: Marcel Dekker, Inc.), 334–340. [Google Scholar]

- Lavin A., Del Pozo A., Maureira M. (2000). Present distribution of Fragaria chiloensis (L.) Duch. in Chile. Plant Genet. Resour. Newsl. 122, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos F. O., Dittz D., Santos V. G., Pires S. F., de Andrade H. M., Salas C. E., et al. (2018). Cysteine proteases from V. cundinamarcensis (C. candamarcensis) inhibit melanoma metastasis and modulate expression of proteins related to proliferation, migration and differentiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 2846. 10.3390/ijms19102846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann R., Babben S., Menger A., Delker C., Quint M. (2019). Development of wild and cultivated plants under Global Warming conditions. Curr. Biol. 29, R1326–R1338. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston A., Cronn R., Ashman T. L. (2014). Fragaria: a genus with deep historical roots and ripe for evolutionary and ecological insights. Am. J. Bot. 101, 1686–1699. 10.3732/ajb.1400140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque A., Debes M., Perera M., Castagnaro A., Arias M. (2019). Reproductive compatibility studies between wild and cultivated strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa) to obtain “bridge species” for breeding programmes. Plant Breed. 138, 229–238. 10.1111/pbr.12681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Yáñez A., Beltrán D., Campano-Romero C., Molinett S., Herrera R., Moya-León M. A., et al. (2017). Glycosylation is important for FcXTH1 activity as judged by its structural and biochemical characterization. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 119, 200–210. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Yáñez A., González M., Carrasco-Orellana C., Herrera R., Moya-León M. A. (2020). Isolation of a rhamnogalacturonan lyase expressed during ripening of the Chilean strawberry fruit and its biochemical characterization. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 146, 411–419. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney L., Sargent D., Abele-Akele F., Wood D., Ward J., Bassil N., et al. (2016). A high density linkage map of the ancestral diploid strawberry, Fragaria iinumae, constructed with single nucleotide polymorphism markers from the IStraw90 array and genotyping by sequencing. Plant Genome 9, 2. 10.3835/plantgenome2015.08.0071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marticorena A. (2019). “Rosaceae Juss,” in Flora de Chile: Berberidopsidaceae - Saxifragaceae. Eds. Rodríguez R., Marticorena A. (Concepción, Chile: Editorial Universidad de Concepción; ), 185–249. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni L., Giampieri F., Suarez J., Gasparrini M., Mezzetti B., Hernandez T., et al. (2019). Isolation of strawberry anthocyanin-rich fractions and their mecganisms of action against murine breast cancer cell lines. Food Funct. 10, 7103–7120. 10.1039/c9fo01721f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello V. J., Gomes M. T. R., Lemos F. O., Delfino J. L., Andrade S. P., Lopes M. T. P., et al. (2008). The gastric ulcer protective and healing role of cysteine proteinases from Carica candamarcensis. Phytomedicine 15, 237–244. 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier R. A., Robles Gil P., Hoffmann M., Pilgrim J., Brooks T., Mittermeier C. G., et al. (2004). Hotspots revisited: Earth"s biologically richest and most endangered terrestrial ecoregions (Mexico City, Mexico: CEMEX; ). [Google Scholar]

- Molinett S., Nuñez F., Moya-León M. A., Zúniga-Hernández J. (2015). Chilean strawberry consumption protects against LPS-induced liver injury by anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capability in Sprague-Dawley rats. Evid. Based. Compl. Alt. Med. 2015 (1). 10.1155/2015/320136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monfort A., Vilanova S., Davis T. M., Arus P. (2006). A new set of polymorphic simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers from a wild strawberry (Fragaria vesca) are transferable to other diploid Fragaria species and to Fragaria × ananassa. Mol. Ecol. Notes 6, 197–200. 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01191.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morales A. L., Duque C. (1987). Aroma constituents of the fruit of the mountain papaya (Carica pubescens) from Colombia. J. Agric. Food Chem. 35, 538–540. 10.1021/jf00076a024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moran E. V. (2020). Simulating the effects of local adaptation and life history on the ability of plants to track climate shifts. AoB Plants 12 (1), plaa008. 10.1093/aobpla/plaa008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira-Muñoz A. (2011). Plant geography of Chile (London, UK and New York, USA: Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg; ). [Google Scholar]

- Moya-León M. A., Moya M., Herrera R. (2004). Ripening of the Chilean papaya fruit (Vasconcellea pubescens) and ethylene dependence of some ripening events. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 34, 211–218. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2004.05.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moya-León M. A., Mattus E., Herrera R. (2019). Molecular events occurring during softening of strawberry fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 615. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers N., Mittermeier R. A., Mittermeier C. G., Da Fonseca G. A. B., Kent J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858. 10.1038/35002501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na J.-K., Wang J., Ming R. (2014). Accumulation of interspersed and sex-specific repeats in the non-recombining region of papaya sex chromosomes. BMC Genomics 15, 335. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano S., Shirasawa K., Hirakawa H., Maeda F., Ishikawa M., Isobe S. (2017). Discrimination of candidate subgenome specific loci by linkage map construction with an S-1 population of octoploid strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). BMC Genomics 18, 374. 10.1186/s12864-017-3762-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njuguna W., Liston A., Cronn R., Ashman T.-L., Bassil N. (2013). Insights into phylogeny, sex function and age of Fragaria based on whole chloroplast genome sequencing. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 66, 17–29. 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oñate F. A., Hasbún R., Mora F., Figueroa C. R. (2018). Linkage disequilibrium and population structure in Fragaria chiloensis revealed by SSR markers transferred from commercial strawberry. Acta Sci. Agron. 40, e34966. 10.4025/actasciagron.v40i1.34966 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ODEPA-CIREN (2019). Catastro Frutícola Nacional, superficie plantada nacional. Santiago de Chile, Chile: Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias (ODEPA) y Centro de Información de Recursos Naturales (CIREN) Available at: https://www.odepa.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Sup-plantada-nacional-web_20.08.2019.xlsx Accessed September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y., Zurn J. D., Bassil N., Edger P. P., Knapp S. J., Whitaker V. M., et al. (2019). The Strawberry DNA Testing Handbook. HortScience 54 (12), 2267–2270. 10.21273/HORTSCI14387-19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y., Chandra S., Lee S. (2020). Development of subgenome specific markers for FaRXf1 conferring resistance to bacterial angular leaf spot in allo-octoploid strawberry. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 20, 1–13. 10.1080/15538362.2019.1709116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Opazo M. C., Lizana R., Pimentel P., Herrera R., Moya-León M. A. (2013). Changes in the mRNA abundance of FcXTH1 and FcXTH2 promoted by hormonal treatments of Fragaria chiloensis fruit. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 77, 28–34. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osterberg J. T., Xiang W., Olsen L. I., Edenbrandt A. K., Vedel S. E., Christiansen A., et al. (2017). Accelerating the domestication of new crops: feasibility and approaches. Trends Plant Sci. 22, 373–384. 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez A. G., Rios J. J., Sanz C., Olías J. M. (1992). Aroma components and free amino acids in strawberry variety Chandler during ripening. J. Agric. Food Chem. 40, 2232–2235. 10.1021/jf00023a036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli R., Thoma G., Matlock M. D. (2019). Environmental sustainability of fruit and vegetable production supply chains in the face of climate change: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 650, 2863–2879. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo O., Pizarro J. L. (2013). Chile: Plantas alimentarias prehispánicas (Arica, Chile: Ediciones Parina EIRL; ). [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Palma C., Fuentes E., Palomo I., Torres C. A., Moya-León M. A., Ramos P. (2018). Linking the platelet antiaggregation effect of different strawberries species with antioxidants: Metabolomic and transcript profiling of polyphenols. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromat. (Blacpma) 17, 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel P., Salvatierra A., Moya-León M. A., Herrera R. (2010). Isolation of genes differentially expressed during development and ripening of Fragaria chiloensis fruit by suppression subtractive hybridization. J. Plant Physiol. 167, 1179–1187. 10.1016/j.plph.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliscoff P., Arroyo M. T. K., Lohengrin C. (2012). Changes in the main vegetation types of Chile predicted under climate change based on a preliminary study: Models, uncertainties and adapting research to a dynamic biodiversity world. Anales Instituto Patagonia (Chile) 40, 81–86. 10.4067/S0718-686X2012000100010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Popenoe W. (1921). The Frutilla, or Chilean strawberry. J. Hered. 12, 457–466. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a102048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pyysalo T., Honkanen E., Hirvi T. (1979). Volatiles of wild strawberries, Fragaria vesca L., compared to those of cultivated berries, Fragaria ananassa cv. Senga Sengana. J. Agric. Food Chem. 27, 19–22. 10.1021/jf60221a042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Retamales J. B., Caligari P., Carrasco B., Saud G. (2005). Current status of the Chilean strawberry and the research needs to convert the species into a commercial crop. HortScience 40, 1633–1634. 10.21273/hortsci.40.6.1633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez R., Marticorena C., Alarcón D., Baeza C., Cavieres L., Finot V. L., et al. (2018). Catálogo de las plantas vasculares de Chile. Gayana Bot. 75, 1–430. 10.4067/S0717-66432018000100001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas P., Almada R. D., Sandoval C., Keller K. E., Martin R. R., Caligari P. D. S. (2013). Occurrence of aphidborne viruses in southernmost South American populations of Fragaria chiloensis ssp. chiloensis. Plant Pathol. 62, 428–435. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2012.02643.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau-Gueutin M., Lercerteau-Kohler E., Barrot L., Sargent D., Monfort A., Simpson D., et al. (2008). Comparative genetic mapping between octoploid and diploid fragaria species reveals a high level of colinearity between their genomes and the essentially disomic behavoir of the cultivated octoploid strawberry. Genetics 179, 2045–2060. 10.1534/genetics.107.083840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez I. (1994). “Andean Fruits,” in Neglected Crops: 1492 from a different perspective, Plant Production and Protection Series N 26. Eds. Hernándo Bermejo J. E., Leon J. (Rome, Italy: FAO; ), 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatierra A., Pimentel P., Moya-León M. A., Caligari P. D. S., Herrera R. (2010). Comparison of transcriptional profiles of flavonoid genes and anthocyanin contents during fruit development of two botanical forms of Fragaria chiloensis ssp. chiloensis. Phytochemistry 71, 1839–1847. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatierra A., Pimentel P., Moya-León M. A., Herrera R. (2014). Biosynthesis of flavonoids in achenes of Fragaria chiloensis ssp. chiloensis. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromat. (Blacpma) 13 (4), 406–414. [Google Scholar]

- Sarricolea P., Herrera-Ossandon M., Meseguer-Ruiz Ó. (2017). Climatic regionalisation of continental Chile. J. Maps 13, 66–73. 10.1080/17445647.2016.1259592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheben A., Wolter F., Batley J., Puchta H., Edwards D. (2017). Towards CRIPS/Cas crops – bringing together genomics and genome editing. New Phytol. 216, 682–698. 10.1111/nph.14702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheldeman X., Romero J. P., Van Damme V., Heyens V., Van Damme P. (2003). Potential of highland papayas (Vasconcella spp.) in southern Ecuador. Lyonia 5, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Scheldeman X., Kyndt T., d' Eeckenbrugge G. C., Ming R., Drew R., Van Droogenbroeck B., et al. (2011). “Vasconcellea,” in Wild crop relatives: Genomic and breeding resources. Ed. Kole C. (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; ), 213–249. 10.1007/978-3-642-20447-0_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier P. (1980). Quantitative composition of volatile constituents in cultivated strawberries, Fragaria ananassa cv. Senga Sengana, Senga Litessa and Senga Gourmella. J. Sci. Food Agric. 31, 487–494. 10.1002/jsfa.2740310511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura K., Hirashima K. (2006). Development and characterization of simple sequence repeats (SSR) as markers to identify strawberry cultivars (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.). J. Jpn. Soc Hortic. Sci. 75, 399–402. 10.2503/jjshs.75.399 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simirgiotis M., Caligari P. D. S., Schmeda-Hirschmann G. (2009). Identification of phenolic compounds from the fruits of the mountain papaya Vasconcellea pubescens A. DC. grown in Chile by liquid chromatography-UV detection-mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 115, 775–784. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.12.071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sooriyapathirana S., Ranaweera L., Perera H., Weebadde C., Finn C., Bassil N., et al. (2019). Using SNP/INDEL diversity patterns to identifiy a core group of genotypes from FVC11, a superior hybrid family of Fragaria virginiana Miller and F. chiloensis (L). Miller. Genet. Resour. Crop Ev. 66, 1691–1698. 10.1007/s10722-019-00819-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Squeo F. A., Olivares N., Olivares S., Pollastri A., Aguirre E., Aravena R., et al. (1999). Grupos funcionales en arbustos desérticos del norte de Chile, definidos sobre la base de las fuentes de agua utilizadas. Gayana Bot. 56, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Staudt G., Drawert F., Tressl R. (1975). Gaschromatographisch-massenspektrometrische differenzierung von Erdbeerarten. II. Fragaria nilgerrensis. Z. Pflanzenzuchtg. 75, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Staudt G. (1962). Taxonomic studies in the genus Fragaria. Typification of Fragaria species known at the time of Linnaeus. Can. J. Bot. 40, 869–886. 10.1139/b62-081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt G. (1999). Systematics and geographic distribution of the American strawberry species: Taxonomic studies in the genus Fragaria (Rosaceae: Potentilleae), (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, USA: University of California Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira R. D., Ribeiro H. A. L., Gomes M. T. R., Lopes M. T. P., Salas C. E. (2008). The proteolytic activities in latex from Carica candamarcensis. Plant Phys. Biochem. 46, 956–961. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennessen J. A., Govindarajulu R., Ashman T.-L., Liston A. (2014). Evolutionary origins and dynamics of octoploid Strawberry subgenomes revealed by dense targeted capture linkage maps. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 3295–3313. 10.1093/gbe/evu261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonaco L. A. B., Gomes F. L., Velazquez-Menendez G., Lopes M. T. P., Salas C. E. (2018). The proteolytic fraction from latex of Vasconcellea cundinamarcensis (P1G10) enhances wound healing of diabetic foot ulcers: A double-blind randomized pilot study. Adv. Ther. 35, 494–502. 10.1007/s12325-018-0684-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulipani S., Mezzetti B., Capocasa F., Bompadre S., Beekwilder J., de Vos C. H. R., et al. (2008). Antioxidants, phenolic compounds, and nutritional quality of different strawberry genotypes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 696–704. 10.1021/jf0719959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich D., Komes D., Olbricht K., Hoberg E. (2007). Diversity of aroma patterns in wild and cultivated Fragaria accessions. Genet. Resour. Crop Ev. 54, 1185–1196. 10.1007/s10722-006-9009-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eynden V., Cueva E., Cabrera O. (1999). Plantas silvestres comestibles del sur del Ecuador - Wild edible plants of southern Ecuador (Quito, Ecuador: Ediciones Abya-Yala; ). [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eynden V., Cueva E., Cabrera O. (2003). Wild foods from Southern Ecuador. Econ. Bot. 57, 576–603. 10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0576:WFFSE]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Droogenbroeck B., Breyne P., Goetghebeur P., Romeijn-Peeters E., Kyndt T., Gheysen G. (2002). AFLP analysis of genetic relationships among papaya and its wild relatives (Caricaceae) from Ecuador. Theor. Appl. Genet. 105, 289–297. 10.1007/s00122-002-0983-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vining K., Salinas N., Tennessen J., Zurn J., Sargent D., Hancock J., et al. (2017). Genotyping-by-sequencing enables linkage mapping in three octoploid cultivated strawberry families. Peer J. 5, e3731. 10.7717/peerj.3731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J., Rodgers-Melnick E., Buckler E. (2018). On the road to breeding 4.0: Unraveling the good, the bad, and the boring of crop quantitative genomics. Ann. Rev. Genet. 52, 421–444. 10.1146/annurev-genet-120116-024846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walraevens V., Jaziri M., Van Beeumen J., Schnek A. G., Kleinschmidt T., Looze Y. (1993). Isolation and preliminary characterization of the cysteine-proteinases from the latex of Carica candamarcensis Hook. Biol. Chem. H. S. 374, 501–506. 10.1515/bchm3.1993.374.7-12.501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Takahashi H. (1999). A land surface water deficit model for an arid and semiarid region: Impact of desertification on the water deficit status in the Loess Plateau, China. J. Climate 12, 244–257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zabetakis I., Holden M. A. (1997). Strawberry flavour: Analysis and biosynthesis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 74, 421–234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.