Abstract

This retrospective cohort study of women with breast cancer evaluates the association of presymptomatic awareness of germline pathogenic BRCA variants and treatment outcomes.

Individuals who carry pathogenic BRCA variants are often identified only after a cancer diagnosis because about half of these persons lack relevant family history (FH),1 and BRCA screening is not routinely performed. Unaffected carriers of pathogenic variants unaware of their genetic status cannot undertake recommended surveillance and prevention measures, including risk-reduction bilateral mastectomy (RRBM), which reduces breast cancer risk in carriers of pathogenic BRCA variants2 and overall mortality in BRCA1 carriers.3 However, worldwide, most carriers decline RRBM.4 We hypothesized that among carriers who decline RRBM and ultimately develop breast cancer, knowing their BRCA status before cancer diagnosis might lead to breast cancer downstaging at diagnosis and measurable downstream benefits.

Methods

We performed a single-institution retrospective review of a cohort of BRCA1/BRCA2 carriers diagnosed with breast cancer (2005-2016). All received guideline-based surveillance and prevention recommendations, including RRBM and risk-reduction salpingo-oophorectomy.5 Demographic, clinical, and pathological data were extracted from medical records, and vital status from the Israel National Cancer Registry. The t test was used for continuous variables, and χ2 for categorical variables. Logistic regression was used for multivariate analyses. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed, with the log-rank test to examine differences beween survival curves. Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox regression. All P values are 2-sided with 95% CIs. The study was approved by the Shaare Zedek Medical Center institutional review board, waiving patient written informed consent for deidentified data.

Results

Of the 105 women BRCA pathogenic variant carriers diagnosed with breast cancer, 83% were Ashkenazi Jewish, mean (SD) age, 50.4 (13.3) years. Of these, 42 were aware of their genotype before diagnosis (BRCA-preDx carriers) and 63 only after diagnosis (BRCA-postDx carriers) (Table). The BRCA-preDx carriers had significantly more suggestive FH and higher socioeconomic index (SI) than BRCA-postDx carriers (Table). Forty of the 42 BRCA-preDx carriers were followed up at the institutional high-risk clinic. Mean age at diagnosis was identical in both groups (50.4 years), but BRCA-preDx carriers were significantly more likely to be diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging and to present with ductal carcinoma in situ (noninvasive disease) or lower-stage invasive disease (Table). There were no significant differences in grade, hormone receptor, or ERBB2 (formerly HER2) expression (Table). BRCA-preDx carriers also had significantly lower rates of axillary dissection and chemotherapy delivery, with none requiring neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Table). Despite their earlier-stage disease, most BRCA-preDx carriers elected bilateral mastectomy as first surgery, significantly more than BRCA-postDx carriers (Table). Logistic regression controlling for age, SI, calendar year at diagnosis, FH, and variant gene indicated that timing of carrier status identification significantly predicted more advanced stage (≥II) at diagnosis. The odds ratios (OR) for BRCA-postDx vs BRCA-preDx carriers were 12.1 (95% CI, 2.7-54.0; P = .001) for advanced clinical stage (cT2-4 or cN+) and 8.1 (95% CI, 2.2-29.4; P = .002) for advanced pathological stage (pT2-4 or pN+, non-NAC patients). Lower SI was also significantly associated with advanced clinical stage (OR, 1.5; 95% CI,1.1-1.9; P = .002) but not with advanced pathological stage (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.99-1.5; P = .06).

Table. Comparison of PreDx vs PostDX Awareness of BRCA Carrier Status in Women With Breast Cancer.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PreDx (n = 42) | PostDx (n = 63) | All (N = 105) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50.4 (14.4) | 50.4 (12.7) | 50.40 (13.3) | NS |

| Year of diagnosis, mean (SD) | 2012.9 (3.1) | 2010.4 (3.3) | 2011.4 (3.4) | <.001 |

| Family historyb,c | .001 | |||

| None-low | 3/42 (7.1) | 22/63 (34.9) | 25/105 (23.8) | |

| Moderate-high | 37/42 (88.1) | 37/63 (58.7) | 74/105 (70.5) | |

| Gene | NS | |||

| BRCA1 | 27/42 (64.3) | 40/63 (63.5) | 67/105 (63.8) | |

| BRCA2 | 15/42 (35.7) | 23/63 (36.5) | 38/105 (36.2) | |

| SI, mean (SD)d | 6.39 (2.45) | 4.99 (2.59) | 5.55 (2.62) | .007 |

| Detection modality | <.001 | |||

| Clinical/self-examination | 4/42 (9.5) | 40/63 (63.5) | 44/105 (41.9) | |

| Mammography | 8/42 (19.0) | 17/63 (27.0) | 25/105 (23.8) | |

| MRI | 27/42 (64.3) | 1/63 (1.6) | 28/105 (26.7) | |

| Tumor characteristics | <.001 | |||

| Pure DCIS | 18/42 (42.9) | 2/63 (3.2) | 20/105 (19.0) | |

| Invasive carcinomae | 24/42 (57.1) | 61/63 (96.8) | 85/105 (81.0) | |

| ER | NS | |||

| Positive | 16/24 (66.7) | 29/61 (47.5) | 45/85 (52.9) | |

| Negative | 8/24 (33.3) | 28/61 (45.9) | 36/85 (42.4) | |

| PR | NS | |||

| Positive | 11/24 (45.8) | 17/61 (27.9) | 28/85 (32.9) | |

| Negative | 11/24 (45.8) | 38/61 (62.3) | 49/85 (57.6) | |

| ERBB2 | NS | |||

| Positive | 1/24 (4.2) | 4/61 (6.6) | 5/85 (5.9) | |

| Negative | 22/24 (91.7) | 56/61 (91.8) | 78/85 (91.8) | |

| Clinical stage at diagnosis | <.001 | |||

| DCIS | 16/42 (38.1) | 2/63 (3.2) | 18/105 (17.1) | |

| T1N0 | 18/42 (42.9) | 17/63 (27) | 35/105(33.3) | |

| >T2 or N1 | 4/42 (9.5) | 33/63 (52.4) | 37/105 (35.2) | |

| Pathologic stage at diagnosis (in non-NAC), No.f | 42 | 49 | 91 | <.001 |

| pTg | <.001 | |||

| pDCIS | 18/42 (42.9) | 2/49(4.1) | 20/91 (22) | |

| pT1 | 19/42 (45.2) | 23/49 (46.9) | 42/91 (46.1) | |

| pT2 | 5/42 (11.9) | 19/49 (38.8) | 24/91 (26.4) | |

| pT3 | 0 | 2/49 (4.1) | 2/91 (2.2) | |

| pN | .009 | |||

| pN0 | 34/42 (81.0) | 28/49 (57.1) | 62/91 (68.1) | |

| pN1-3 | 6/42 (14.3) | 19/49 (38.8) | 25/91 (27.5) | |

| pTNMch | <.001 | |||

| 0-I | 36/42 (85.7) | 19/49 (38.8) | 55/91 (60.4) | |

| II-IV | 6/42 (14.3) | 30/49 (61.2) | 36/91 (39.6) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Breast surgery | <.001 | |||

| Unilateral | 14/42 (33.3) | 49/63 (77.8) | 63/105 (60) | |

| Bilateral | 27/42 (64.3) | 10/63 (15.9) | 37/105 (35.2) | |

| Axillary surgery | <.001 | |||

| None | 1/42 (2.4) | 2/63 (3.2) | 3/105 (2.9) | |

| SNLB | 36/42 (85.7) | 32/63 (50.8) | 68/105 (64.8) | |

| ALND | 3/42 (7.2)i | 22/63 (34.9) | 25/105 (23.8)h | |

| Chemotherapy | <.001 | |||

| None | 23/42 (54.8) | 3/63 (4.8) | 26/105 (24.8) | |

| Anyj | 12/42 (28.6) | 50/63 (79.4) | 62/105 (59) | |

| Neoadjuvant | 0 | 14/63 (22.2) | 14/105 (13.3) | .001 |

| Adjuvant | 12/42 (28.6) | 39/63 (61.9) | 51/105 (48.6) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ER, estrogen receptor; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NS, nonsignificant; PR, progesterone receptor; preDX, BRCA status awareness before diagnosis; postDX, BRCA status awareness only after diagnosis; SI, socioeconomic index; SNLB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

The t test was used for continuous variables and χ2 for categorical variables; 2-sided P values are for comparison between BRCA-preDx and BRCA-postDx groups.

Family history defined as previously published.1

Percentages indicated are for the proportion of all cases indicated in the denominator (where there are missing data, the sum of percentages is <100%). Rates of missing data were similar in both groups for all the variables (NS). Except for clinical stage and chemotherapy delivery, the missing rate in all variables is less than 10%.

The SI was extracted from Israel Central Bureau of Statistics database. This index, scaled from 1 (low) to 10 (high) is address-based in cities and locality-based for smaller municipalities. For 6 Jerusalem patients with missing street addresses, we used the mean SI for all Jerusalem residents in the study.

Hormone receptor and ERBB2 status are indicated only for invasive tumors.

Pathology staging was performed in patients who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

There were no pT4 in either group of patients.

The composite pTNM stage was indicated in all charts reviewed, including in those cases where specific parameters (eg, pT or pN) were not indicated.

Includes 1 patient with SNLB converted to ALND.

Three patients received both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy.

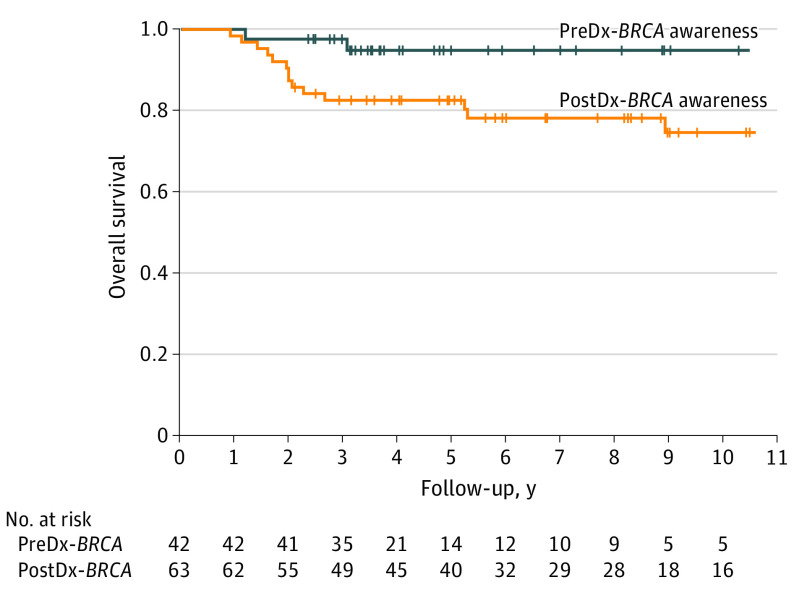

Awareness of genotype before diagnosis was associated with significantly better overall survival (Figure): 2 of 42 (4.8%) BRCA-preDx carriers and 16 of 63 (25.4%) BRCA-postDx carriers died, yielding 5-year overall survival of 94% (SE 4%) vs 78% (SE 5%), respectively (P = .03). Controlled for age, SI, calendar year at diagnosis, FH, and variant gene, the hazard ratio (HR) for overall mortality in BRCA-preDx vs BRCA-postDx carriers was 0.16 (95% CI, 0.02-1.4; P = .10). Factors associated with survival were higher SI (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.6-0.97; P = .03), variant gene (BRCA2 vs BRCA1) (HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.03-0.75; P = .02) and age at diagnosis (HR, 1.047; 95% CI, 1.003-1.093; P = .04).

Figure. Overall Survival in Carriers of BRCA Pathogenic Variants Diagnosed With Breast Cancer Who Were Aware of Their BRCA Status Before vs After Cancer Diagnosis.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival in BRCA1/BRCA2 carriers diagnosed with breast cancer. PreDx-BRCA indicates carriers who were aware of BRCA status before their breast cancer diagnosis; postDx-BRCA, carriers who became aware of their BRCA status only after their breast cancer diagnosis. Vertical hatches represent censored individuals. Overall survival was higher in preDx-BRCA vs PostDx-BRCA carriers: 5-year survival rates were 94% (SE 4%) in pre-Dx-BRCA carriers and 78% (SE 5%) in postDx-BRCA carriers (P = .03). The hazard ratio for overall mortality for BRCA-preDx carriers vs BRCA-postDx carriers, controlled for calendar year at diagnosis, was 0.20 (95% CI, 0.04-0.93) (P = .04). Controlled for age, SI (socioeconomic index), family history, calendar year at diagnosis and variant gene, the hazard ratio was 0.16 (95% CI, 0.02-1.4; P = .10). Log-rank test was used to examine statistical differences in survival curves. Hazard ratio was calculated using Cox regression.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that prior awareness of BRCA pathogenic variant carrier status may be beneficial even in carriers who decline RRBM and later develop breast cancer. Prediagnostic awareness was associated with diagnosis by magnetic resonance imaging, earlier-stage breast cancer, and less morbid axillary surgery and chemotherapy. To our knowledge, this is the first report to document a possible survival advantage for presymptomatic identification of BRCA carrier status in carriers who decline RRBM.

Study limitations include retrospective nature and limited sample size. Also, the data did not permit comparison of risk-reduction salpingo-oophorectomy rates. Nevertheless, the identical age at diagnosis in both groups suggests lack of substantial bias, and analyses were controlled for possible confounders.

These results provide further support for BRCA1/BRCA2 screening in unaffected women, particularly in populations such as Ashkenazi Jews, with high BRCA1/BRCA2 carrier rates.6

References

- 1.Gabai-Kapara E, Lahad A, Kaufman B, et al. Population-based screening for breast and ovarian cancer risk due to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(39):14205-14210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415979111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchetti C, De Felice F, Palaia I, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy: a meta-analysis on impact on ovarian cancer risk and all cause mortality in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s12905-014-0150-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heemskerk-Gerritsen BAM, Jager A, Koppert LB, et al. Survival after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy in healthy BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;177(3):723-733. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05345-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metcalfe K, Eisen A, Senter L, et al. ; Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group . International trends in the uptake of cancer risk reduction strategies in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Br J Cancer. 2019;121(1):15-21. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0446-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daly MB, Pilarski R, Yurgelun MB, et al. ; National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN guidelines insights: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(4):380-391. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domchek S, Robson M. Broadening criteria for BRCA1/2 evaluation: placing the USPSTF recommendation in context. JAMA. 2019;322(7):619-621. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]