Key Points

Question

What are the characteristics of semicircular canals and endolymphatic hydrops during medical treatment, including treatment with diuretic therapy, among patients with Ménière disease?

Findings

In this cohort study of 55 patients with Ménière disease who received treatment over a 2-year study period, vestibuloocular reflex gain in the vertical semicircular canals decreased, while vestibuloocular reflex gain in the horizontal semicircular canals was maintained. The vestibular endolymphatic hydrops volume ratio increased, but the number of vertiginous episodes decreased during treatment with diuretic therapy.

Meaning

The study’s findings suggest that deterioration in the vertical semicircular canals and enlargement of endolymphatic hydrops volume may progress during the early stage of Ménière disease, and medical treatment, including treatment with diuretic therapy, may not be associated with reductions in endolymphatic hydrops volume.

Abstract

Importance

Vertical semicircular canals and endolymphatic hydrops play important roles in the pathophysiological mechanisms of Ménière disease. However, their characteristics and associations with disease progression during medical treatment have not been determined.

Objective

To examine the function of both the horizontal and vertical semicircular canals in patients with Ménière disease and to evaluate the change in endolymphatic hydrops volume during medical treatment, including treatment with diuretic therapy, over a 2-year period.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective longitudinal observational cohort study included 55 patients with definite unilateral Ménière disease and was performed in a tertiary care hospital in Japan. Participants were enrolled between April 1, 2017, and January 31, 2018, and those with vestibular migraine were excluded. All participants received education regarding diet and lifestyle modifications and treatment with betahistine mesylate (36 mg daily) and/or an osmotic diuretic (42-63 mg daily). Patients were followed up for vertigo and hearing evaluations at least once per month for more than 12 months and were instructed to record episodes of vertigo in a self-check diary. Audiometry was performed monthly, video head impulse testing and caloric testing were performed every 4 months, and magnetic resonance imaging was conducted annually. Data were analyzed from May 15, 2017, to January 31, 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Neurootological testing to evaluate vestibuloocular reflex gain over time, magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate the change in endolymphatic hydrops volume over time, and monthly vertigo and hearing evaluations for more than 12 months.

Results

Among 55 participants with definite Ménière disease, 32 patients (58.2%) were female, and the mean (SD) age was 59.0 (15.1) years. The median disease duration was 2 years (interquartile range, 0-4 years), with 43 patients (78.2%) having an early stage (ie, disease duration ≤4 years) of Ménière disease. Over the 2-year study period, the vestibuloocular reflex gain decreased from 0.76 to 0.56 in the superior semicircular canals, for a difference of 0.20 (95% CI, 0.14-0.26) and from 0.68 to 0.50 in the posterior semicircular canals, for a difference of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.14-0.22). The maximum slow-phase velocity and vestibuloocular reflex gain in the horizontal semicircular canals were maintained. The volume ratio of vestibular endolymphatic hydrops increased from 19.7% to 23.3%, for a difference of 3.6% (95% CI, 1.4%-5.8%). The frequency of vertiginous episodes decreased, and the hearing level over the study period worsened from 40.9 dB to 44.5 dB, for a difference of 3.5 dB (95% CI, 0.7-6.4 dB).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, during a 2-year period of medical treatment among patients with Ménière disease, vestibuloocular reflex gain decreased in the vertical semicircular canals but was maintained in the horizontal semicircular canals; the endolymphatic hydrops volume ratio increased, and the frequency of vertiginous episodes decreased. These findings describe the pathological progression of chronic Ménière disease and expand the understanding of its pathophysiological characteristics during the early stage of disease.

This cohort study examines the characteristics of the horizontal and vertical semicircular canals and the change in endolymphatic hydrops volume during medical treatment, including treatment with diuretic therapy, among patients with Ménière disease over a 2-year period.

Introduction

Ménière disease is a common inner ear disease that is characterized by episodic vertigo, fluctuating sensorineural hearing loss, and tinnitus. The chronic course of Ménière disease has been explored in several studies and was summarized in a review.1 This research reported that vertiginous episodes improved, but both vestibular and hearing function deteriorated. In previous studies, vestibular function in patients with Ménière disease was typically evaluated using caloric testing, which assesses the function of the horizontal semicircular canal. However, the function of the vertical semicircular canals has not been extensively examined in patients with Ménière disease. Recently, the findings of vertical semicircular canal examinations using the video head impulse test (vHIT) have been reported to have a diagnostic association with Ménière disease, especially in the posterior semicircular canals of patients with Ménière disease.2

In contrast, the characteristics of endolymphatic hydrops, which is a pathological feature of Ménière disease in the inner ear,3,4 have not been characterized during the chronic course of Ménière disease. One of the main aims in the treatment of Ménière disease symptoms is to reduce endolymphatic hydrops volume, which involves treatments for endolymphatic hydrops that include a low-salt diet and diuretic therapy. Endolymphatic hydrops volume is expected to decrease with the remission of Ménière disease symptoms; however, endolymphatic hydrops volume has been shown to increase with deterioration in inner ear function during medical treatment in a small number of patients with Ménière disease.5 Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to characterize the function of all semicircular canals, including the vertical semicircular canals, in patients with Ménière disease over a long-term period. The secondary purpose of this study was to examine the nature of the long-term changes in endolymphatic hydrops volume during medical treatment among a larger cohort than that of the previous study.

Although the details of the 2 physiological phenomena involved in the progression of Ménière disease have not been fully elucidated, an association between semicircular canal function and endolymphatic hydrops volume has been suggested.2 Patients with Ménière disease can have normal vHIT results despite worse or absent caloric results, despite the fact that both tests stimulate the horizontal semicircular canal.2 The same difference between the results of the vHIT and caloric testing has been reported in patients with Ménière disease,6,7 and this difference is used as a diagnostic marker for Ménière disease.7,8 Endolymphatic hydrops volume has been suggested to be associated with this asymmetry in vestibuloocular reflex (VOR) responses.9,10 Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Fukushima et al2 reported that endolymphatic hydrops volume in the vestibule is associated with the caloric test response but not with the vHIT response in patients with Ménière disease.

In the present study, we prospectively investigated vHIT findings for all semicircular canals and caloric test responses in patients with Ménière disease. We routinely performed 3-T MRIs of the inner ear using intravenous administration of gadolinium to visualize endolymphatic hydrops.11 During this study, we repeatedly measured the volume ratio of the vestibular part of endolymphatic hydrops by processing MRI results semiquantitatively,2 and we analyzed the change in endolymphatic hydrops volume. We aimed to characterize the long-term progression of VOR responses in patients with Ménière disease and to assess whether endolymphatic hydrops volume increased. We also aimed to explore whether there was a difference in VOR response for each semicircular canal (especially the vertical semicircular canals) over the long term in patients with Ménière disease and whether the change in endolymphatic hydrops volume was associated with VOR response to expand our understanding of the pathophysiological characteristics of Ménière disease.

Methods

Patients

This prospective longitudinal observational cohort study enrolled 55 participants with definite unilateral Ménière disease12 from April 1, 2017, to January 31, 2018. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kansai Rosai Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent and received no stipend. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

We determined in advance whether patients met the diagnostic criteria for vestibular migraine and, if so, they were excluded. All participants received neurootological testing and MRI scans on the same day within the 3 months after their first consultation at Kansai Rosai Hospital, a tertiary care hospital in Hyogo, Japan. Participants received educational information regarding diet and lifestyle modifications and a prescription for a betahistine mesylate medication (36 mg daily) and/or an osmotic diuretic medication (42-63 mg daily). Patients were followed up for vertigo and hearing evaluations at least once per month for more than 12 months, and they were instructed to record episodes of vertigo in a self-check diary13 when the episodes lasted between 20 minutes and 24 hours and were associated with the sensation of motion. We performed audiometry once a month, vHIT and caloric testing every 4 months, and MRI scans annually. These tests were performed on the same day if the timing of individual tests coincided.

Vestibular and Auditory Evaluation

Three-dimensional vHIT was performed as previously described.2 In brief, patients received abrupt, brief, and unpredictable head rotation testing from trained otologists to measure the VOR gain (classically defined as eye velocity divided by head velocity during testing) in each semicircular canal plane using a video oculography device (ICS Impulse; Natus [formerly GN Otometrics]). Individual VOR gains were automatically calculated using the ICS Impulse device software (OTOsuite Vestibular, version 4.00, build 1286; Natus); in ICS Impulse testing, VOR gain is defined as the area under the desiccated eye velocity curve divided by the area under the head velocity curve.

Bithermal caloric testing was performed as previously described.2,14 Induced nystagmus was recorded using an electronystagmogram, and the maximum slow-phase velocity of the nystagmus was measured after each irrigation to assess the absolute value describing the function of the horizontal semicircular canal.

Hearing function was assessed using pure-tone audiometry and evaluated on the basis of the 4-tone average (calculated as the sum of the hearing levels [0.5 dB, 1.0 dB, 2.0 dB, and 3.0 dB] divided by 4) according to the modified 1995 criteria of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.12 Patients’ disease stage was defined on the basis of their hearing function. Disease stages 1, 2, 3, and 4 were categorized according to the 4-tone averages of the worst audiometric results (<25 dB for stage 1, 25-40 dB for stage 2, 41-70 dB for stage 3, and >70 dB for stage 4) in the 6 months before treatment.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed as previously described.2,5 In brief, a standard dose (0.2 mL/kg) of gadoteridol (ProHance; Bracco) was injected intravenously, and an MRI scan was performed 4 hours later using a 3-T MRI unit (MAGNETOM Verio; Siemens Healthineers) equipped with a receive-only 32-channel phased-array coil. All patients underwent heavily T2-weighted magnetic resonance cisternography for the anatomical referencing of total lymph fluid volume and heavily T2-weighted 3-dimensional fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, with inversion times of 2250 ms and 2050 ms. The HYDROPS (hybrid of reversed image of positive endolymph signal and native image of positive perilymph signal) imaging method was used to visualize endolymphatic hydrops; the sequence parameters have been described previously.11

Endolymphatic hydrops images were evaluated as previously described.2 In brief, an image was created by multiplying the results of magnetic resonance cisternography and HYDROPS imaging (ie, a HYDROPS-Mi2 image) using the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine viewing program (OsiriX, version 9.5; Pixmeo).5,15 The regions of interest (ROIs) for the contouring of the vestibule on the magnetic resonance cisternography were copied to the HYDROPS-Mi2 image. Using the OsiriX histogram function, we calculated the total number of pixels in the ROI and the number of pixels with negative signal intensity, which represent areas of vestibular endolymphatic hydrops, in the ROI.5 The volume ratio of vestibular endolymphatic hydrops was computed as the ratio of the number of negative signal intensity pixels in the ROI divided by the total number of pixels in the ROI.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS JMP Discovery software, version 14.3.0 (SAS Institute), and IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 26.0 (IBM). Data analysis was performed from May 15, 2017, to January 31, 2020. The effect size for the difference between compared values was reported as the absolute difference and 95% CIs, and the effect size for the difference in values between more than 2 groups or periods was reported as the eta-squared value and 95% CIs. A difference of 0.01 was considered a small effect size, a difference of 0.09 a medium effect size, and a difference of 0.25 a large effect size. The 95% CIs were provided to describe the precision of the estimates and the range within which the true effect size could be found.

Results

Among 55 participants with Ménière disease, 32 patients (58.2%) were female, and the mean (SD) age was 59.0 (15.1) years. Patient characteristics (age range and sex), disease duration, disease stage, treatments received, pure-tone audiometric results, VOR gain, number of vertiginous episodes per month, and vestibular endolymphatic hydrops volume ratio at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months are shown in the Table. The median disease duration was 2 years (interquartile range, 0-4 years), with 43 patients (78.2%) having a disease duration of 4 years or less.

Table. Characteristics of Patients With Ménière Disease.

| Sex | Age range, y | Duration of disease, y | Disease stagea | Treatment receivedb | Outcome | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 mo | 24 mo | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PTA results, dB | hVOR gain | pVOR gain | sVOR gain | Vertiginous episodes/mo, No. | vEH ratio, % | PTA results, dB | hVOR gain | pVOR gain | sVOR gain | Vertiginous episodes/mo, No. | vEH ratio, % | PTA results, dB | hVOR gain | pVOR gain | sVOR gain | Vertiginous episodes/mo, No. | vEH ratio, % | |||||

| F | 40s | 4 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 56.3 | 0.38 | 0.32 | NA | 0.17 | 29.5 | 63.8 | 0.39 | 0.35 | NA | 0 | 33.7 | 56.3 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0 | 34.9 |

| F | 50s | 4 | 3 | Diuretic | 47.5 | 0.76 | 0.50 | NA | 5.00 | 18.3 | 61.3 | 0.75 | 0.21 | NA | 5.00 | 30.9 | 55.0 | 0.75 | 0.27 | NA | 6.00 | 37.7 |

| M | 40s | 2 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 48.8 | 0.87 | 1.11 | 0.76 | 10.00 | 10.9 | 65.0 | 1.04 | 0.70 | 0.55 | 8.00 | 15.3 | 77.5 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0 | 19.6 |

| M | 50s | 1 | 4 | Diuretic and betahistine | 96.3 | 0.71 | 0.13 | 0.82 | 13.00 | 29.3 | 115.0 | 0.87 | 0.32 | 0.64 | 2.00 | 36.7 | 115.0 | 0.87 | 0.13 | 0.63 | 0 | 38.0 |

| M | 60s | 18 | 4 | Diuretic and betahistine | 76.3 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.99 | 1.33 | 29.1 | 82.5 | 1.19 | 0.63 | 0.83 | 1.67 | 36.4 | 76.3 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 1.67 | 43.7 |

| M | 50s | 7 | 2 | Diuretic and betahistine | 30.0 | 0.45 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 15.4 | 27.5 | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.17 | 14.3 | 27.5 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0 | 15.7 |

| F | Teens | 1 | 1 | Diuretic | 2.5 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 10.00 | 9.6 | 2.5 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.60 | 2.00 | 13.4 | 1.3 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 10.3 |

| M | 40s | 5 | 3 | Diuretic | 47.5 | 0.85 | 0.34 | 1.03 | 0.17 | 33.5 | 50.0 | 0.91 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0 | 22.0 | 51.3 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0 | 26.1 |

| F | 20s | 16 | 1 | Diuretic | 7.5 | 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 10.00 | 21.6 | 10.0 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 10.00 | 32.7 | 8.8 | 1.04 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 10.00 | 30.4 |

| F | 70s | 3 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 56.3 | 1.03 | 0.73 | 0.93 | 0.17 | 23.9 | 63.8 | 1.09 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0 | 20.8 | 67.5 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0 | 30.8 |

| M | 50s | 9 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 63.8 | 1.19 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.17 | 36.6 | 47.5 | 1.34 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0 | 21.5 | 46.3 | 1.25 | 0.51 | 0.88 | 0 | 23.3 |

| M | 50s | 1 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 7.5 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 1.01 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0 | 11.7 | 6.3 | 1.05 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0 | 10.3 |

| F | 70s | 3 | 1 | Diuretic | 18.8 | 1.05 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 16.6 | 21.3 | 1.20 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0 | 14.4 | 21.3 | 1.05 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0 | 18.8 |

| F | 60s | 21 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 62.5 | 1.08 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 2.00 | 21.2 | 58.8 | 1.17 | 0.68 | 0.38 | 3.00 | 21.7 | 58.8 | 1.10 | 0.66 | 0.36 | 4.00 | 27.3 |

| M | 70s | 17 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 56.3 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.17 | 25.8 | 51.3 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0 | 19.3 | 50.0 | 1.12 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0 | 6.8 |

| M | 50s | 1 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 12.5 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.17 | 10.2 | 15.0 | 1.18 | 0.42 | 0.57 | 0 | 11.3 | 18.8 | 1.01 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0 | 9.0 |

| F | 50s | 0.5 | 2 | Diuretic | 32.5 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 2.00 | 13.3 | 21.3 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.49 | 0 | 11.3 | 20.0 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0 | 22.7 |

| M | 50s | 1 | 3 | Diuretic | 66.3 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 2.00 | 4.2 | 86.3 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0 | 23.0 | 112.5 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0 | 20.2 |

| M | 60s | 35 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 8.75 | 1.03 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.17 | 10.3 | 8.75 | 1.09 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 0 | 12.0 | 8.8 | 1.09 | 0.44 | 0.76 | 0 | 16.0 |

| F | 60s | 3 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 43.8 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.17 | 18.1 | 47.5 | 0.91 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 21.5 | 45.0 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 19.6 |

| M | 70s | 3 | 2 | Betahistine | 37.5 | 1.87 | 1.01 | 1.54 | 1.00 | 19.4 | 37.5 | 0.99 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.33 | 18.6 | 37.5 | 1.21 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0 | 21.5 |

| M | 60s | 5 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 45.0 | 1.02 | 0.74 | 1.03 | 0.17 | 39.2 | 60.0 | 0.66 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 24.0 | 66.3 | 0.95 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 47.6 |

| M | 70s | 6 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 65.0 | 1.08 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 12.00 | 27.3 | 63.8 | 0.95 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0 | 33.3 | 65.0 | 0.92 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0 | 35.2 |

| F | 60s | 0 | 3 | Betahistine | 46.3 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 4.00 | 0.17 | 8.2 | 43.8 | 1.04 | 0.74 | 0.46 | 0 | 18.8 | 43.8 | 1.01 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0 | 13.4 |

| F | 50s | 0 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 57.5 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.82 | 2.00 | 14.9 | 63.8 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 2.00 | 26.7 | 63.8 | 0.94 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 2.00 | 42.4 |

| F | 70s | 6 | 3 | Betahistine | 43.8 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.94 | 0.17 | 30.3 | 46.3 | 0.94 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0 | 21.3 | 48.8 | 0.98 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0 | 28.5 |

| F | 80s | 3 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 56.3 | 1.85 | 0.69 | 1.03 | 0.17 | 47.5 | 53.8 | 1.40 | 0.59 | 0.72 | 0 | 34.8 | 51.3 | 1.40 | 0.52 | 0.79 | 0 | 59.3 |

| F | 70s | 3 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 61.3 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 26.1 | 62.5 | 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 24.5 | 67.5 | 0.60 | 0.12 | 0.55 | 0 | 29.3 |

| F | 60s | 4 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 42.5 | 1.01 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 23.7 | 40.0 | 1.08 | 0.57 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 29.4 | 33.8 | 1.12 | 0.32 | 0.85 | 0.33 | 36.7 |

| M | 50s | 0 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 17.5 | 1.24 | 0.75 | 1.34 | 0.17 | 19.2 | 21.3 | 0.97 | 0.60 | 0.99 | 0.33 | 15.4 | 21.3 | 1.02 | 0.57 | 0.84 | 0.33 | 27.4 |

| F | 40s | 0 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 5.0 | 0.32 | 0.64 | 0.29 | 14.00 | 34.9 | 6.3 | 0.20 | 0.88 | 0.42 | 3.00 | 18.4 | 7.5 | 0.37 | 0.71 | 0.40 | 0 | 19.7 |

| M | 40s | 0 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 20.0 | 1.12 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.30 | 3.7 | 17.5 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0 | 5.7 | 18.8 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0 | 5.1 |

| F | 60s | 1 | 4 | Diuretic and betahistine | 72.5 | 1.03 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 3.00 | 12.4 | 77.5 | 1.23 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 3.00 | 8.5 | 77.5 | 1.21 | 0.45 | 0.62 | 4.00 | 9.5 |

| F | 50s | 2 | 4 | Diuretic and betahistine | 73.8 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 4.00 | 34.2 | 72.5 | 0.91 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 6.00 | 33.5 | 82.5 | 0.99 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 6.00 | 40.5 |

| M | 50s | 0 | 2 | Diuretic and betahistine | 27.5 | 0.86 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 2.00 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 1.04 | 0.24 | 0.58 | 2.33 | 13.9 | 41.3 | 1.03 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 2.67 | 23.7 |

| F | 60s | 3 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 13.8 | 1.39 | 0.78 | 1.09 | 0.17 | 7.4 | 17.5 | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.04 | 0 | 10.7 | 17.5 | 1.10 | 0.42 | 0.91 | 0 | 14.5 |

| F | Teens | 0 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 10.0 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.17 | 22.5 | 68.8 | 1.16 | 0.58 | 0.87 | 0 | 26.5 | 78.8 | 0.99 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0 | 29.2 |

| M | 70s | 2 | 3 | Diuretic | 70.0 | 0.92 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.17 | 15.6 | 71.3 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0 | 17.7 | 71.3 | 1.06 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0 | 16.9 |

| M | 60s | 3 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 65.0 | 1.09 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 30.00 | 22.6 | 65.0 | 1.19 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 12.00 | 24.0 | 66.3 | 1.01 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0 | 25.0 |

| F | 50s | 1 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 20.0 | 1.05 | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.17 | 19.1 | 22.5 | 1.10 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0 | 9.2 | 25.0 | 1.23 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0 | 14.4 |

| F | 70s | 0 | 2 | Diuretic and betahistine | 35.0 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 4.00 | 6.2 | 41.3 | 0.92 | 0.39 | 0.74 | NA | 17.2 | 41.3 | 0.92 | 0.39 | 0.74 | 3.00 | 19.3 |

| F | 40s | 1 | 1 | Diuretic | 12.5 | 1.26 | 0.61 | NA | 0.17 | 9.7 | 11.3 | 1.26 | 0.43 | NA | 0 | 14.5 | 13.8 | 1.44 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.17 | 8.4 |

| F | 30s | 0 | 1 | Diuretic | 7.5 | 1.01 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 14.9 | 3.8 | 0.86 | 0.57 | 0.39 | 0 | 9.4 | 2.5 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.39 | 0 | 14.5 |

| F | 70s | 10 | 4 | Betahistine | 81.3 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.17 | 21.0 | 65.0 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.58 | 0 | 23.0 | 65.0 | 0.45 | 0.14 | 0.49 | 0 | 28.7 |

| M | 40s | 0 | 1 | Diuretic | 1.3 | 1.24 | 0.71 | 0.78 | 0.17 | 17.5 | 1.3 | 1.33 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0 | 10.6 | 2.5 | 1.24 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 0 | 8.4 |

| F | 70s | 4 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 46.3 | 0.95 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.17 | 21.8 | 57.5 | 0.85 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0 | 36.8 | 48.8 | 0.89 | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.17 | 34.1 |

| M | 60s | 1 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 55.0 | 1.06 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 27.7 | 60.0 | 1.15 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 24.0 | 62.5 | 1.22 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 12.5 |

| F | 70s | 0 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 55.0 | 1.04 | 0.78 | 0.38 | 3.00 | 6.4 | 46.3 | 0.85 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0 | 18.3 | 46.3 | 0.80 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0 | 12.2 |

| F | 50s | 0 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 51.3 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.33 | 17.9 | 52.5 | 1.17 | 0.75 | 0.29 | 0 | 22.5 | 48.8 | 1.02 | 0.75 | 0.29 | 0 | 26.4 |

| F | 50s | 0 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 23.8 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 10.00 | 10.4 | 33.8 | 0.96 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 4.00 | 15.6 | 23.8 | 1.14 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0 | 16.4 |

| M | 60s | 0 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 60.0 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 8.00 | 16.7 | 56.3 | 0.80 | 0.36 | 0.52 | 0 | 19.1 | 53.8 | 0.80 | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0 | 18.0 |

| M | 70s | 0 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 50.0 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.17 | 18.3 | 56.3 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0 | 22.2 | 53.8 | 1.19 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 1.00 | 26.1 |

| F | 40s | 0 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 6.3 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.17 | 25.2 | 5.0 | 1.05 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0 | 20.1 | 6.3 | 0.98 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.33 | 38.7 |

| F | 60s | 3 | 1 | Diuretic and betahistine | 13.8 | 1.01 | 0.66 | 0.85 | 3.00 | 9.2 | 15.0 | 0.94 | 0.48 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 7.8 | 13.8 | 1.01 | 0.48 | 0.77 | 0 | 11.1 |

| F | 80s | 0 | 3 | Diuretic and betahistine | 61.3 | 0.91 | 0.40 | 0.66 | 0.17 | 29.3 | 56.3 | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.40 | 0 | 21.2 | 55.0 | 0.91 | 0.15 | 0.55 | 0 | 4.8 |

Abbreviations: hVOR, horizontal vestibuloocular reflex; NA, not applicable; PTA, pure-tone audiometry; pVOR, posterior vestibuloocular reflex; sVOR, superior vestibuloocular reflex; vEH, vestibular endolymphatic hydrops.

Disease stage was defined based on hearing function. Stages were categorized according to the 4-tone averages of the worst audiometric results (<25 dB for stage 1, 25–40 dB for stage 2, 41–70 dB for stage 3, and >70 dB for stage 4) in the 6 months before treatment. Hearing function was assessed using pure-tone audiometry and evaluated on the basis of the 4-tone average (calculated as the sum of the hearing levels [0.5 dB, 1.0 dB, 2.0 dB, and 3.0 dB] divided by 4) according to the modified 1995 American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation criteria.12

Patients received osmotic diuretic (42-63 mg daily) and/or betahistine mesylate (36 mg daily) medications.

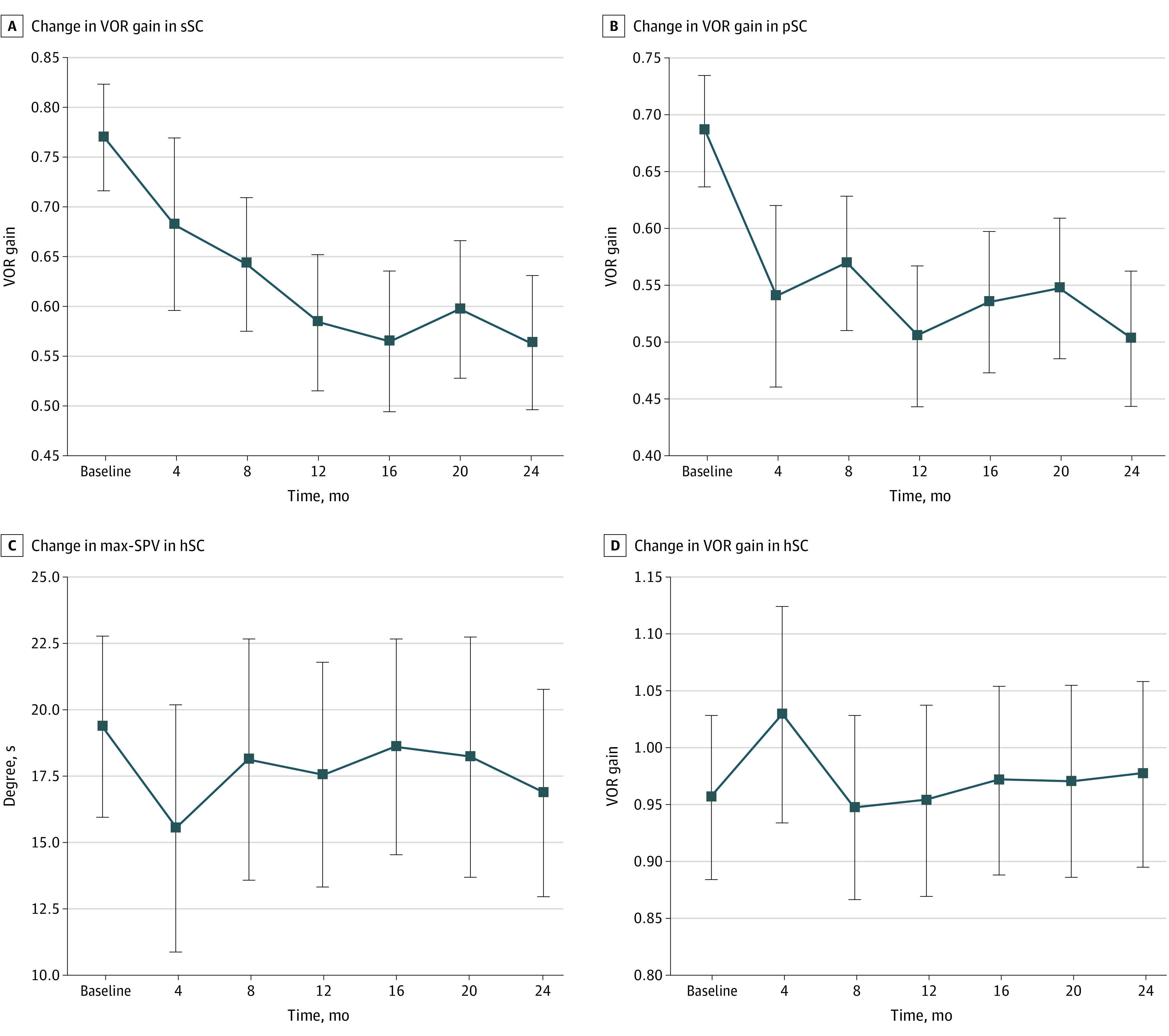

Serial changes in the vestibular function of patients with Ménière disease, which were assessed using caloric testing and vHIT every 4 months for 2 years, are shown in Figure 1. The mean VOR gain in the affected superior semicircular canal decreased from 0.76 at the first examination to 0.56 at 24 months, for a difference of 0.20 (95% CI, 0.14-0.26) (Figure 1A). Each mean VOR gain was 0.76 at the first examination, 0.68 at 4 months, 0.64 at 8 months, 0.58 at 12 months, 0.56 at 16 months, 0.59 at 20 months, and 0.56 at 24 months (effect size, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.22-0.40) (Figure 1A). The mean VOR gain in the affected posterior semicircular canal decreased from 0.68 at the first examination to 0.50 at 24 months, for a difference of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.14-0.22) (Figure 1B). Each mean VOR gain was 0.68 at the first examination, 0.54 at 4 months, 0.56 at 8 months, 0.50 at 12 months, 0.53 at 16 months, 0.54 at 20 months, and 0.50 at 24 months (effect size, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.24-0.40) (Figure 1B). The maximum slow-phase velocity in the affected horizontal semicircular canal was 19.3 degrees per second at the first examination and 15.5 degrees per second at 4 months, for a difference of 3.8 degrees per second (95% CI, −0.2 to 7.8 degrees per second) (Figure 1C), and the mean VOR gain in the affected horizontal semicircular canal was 1.03 at 4 months and 0.94 at 8 months, for a difference of 0.09 (95% CI, 0-0.17) (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Serial Changes in Vestibular Function.

Changes were assessed using the caloric test and the vertical head impulse test every 4 months. Error bars represent 95% CIs. hSC indicates horizontal semicircular canal; max-SPV, maximum slow-phase velocity; pSC, posterior semicircular canal; sSC, superior semicircular canal; VOR, vestibuloocular reflex. A, Change in VOR gain in sSC. B, Change in VOR gain in pSC. C, Change in max-SPV in hSC. D, Change in VOR gain in hSC.

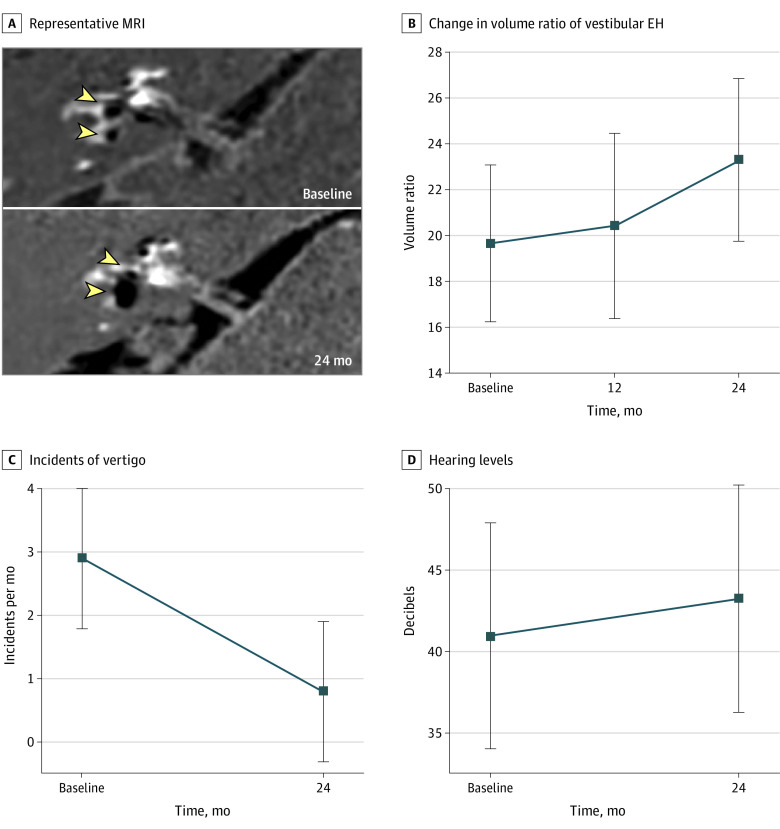

The vestibular endolymphatic hydrops volume change in a representative patient with Ménière disease over the 2-year period is shown in Figure 2. The MRI results of the patient indicate mild endolymphatic hydrops in the right cochlea and vestibule at the first examination (Figure 2A, upper half) and significant endolymphatic hydrops in the right cochlea and vestibule 2 years later (Figure 2A, lower half). The mean vestibular endolymphatic hydrops volume ratio increased from 19.7% at the first examination to 23.3% at 24 months, for a difference of 3.6% (95% CI, 1.4% to 5.8%). Each mean volume ratio was 19.7% at the first examination, 20.4% at 12 months, and 23.3% at 24 months (effect size, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.02-0.18) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Changes in Endolymphatic Hydrops Volume, Frequency of Vertiginous Episodes, and Hearing Levels .

EH indicates endolymphatic hydrops and MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. A, Representative MRI. Yellow arrowheads indicate vestibular EH, and black areas represent EH in the labyrinth. Upper half of image indicates mild EH in the right cochlea and vestibule at the first examination. Lower half of image indicates substantial EH in the right cochlea and vestibule 2 years later. B, Change in volume ratio of vestibular EH. Error bars represent 95% CIs. C, Incidents of vertigo. Error bars represent 95% CIs. D, Hearing levels. The y-axis indicates the dB threshold of the 4-tone average. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

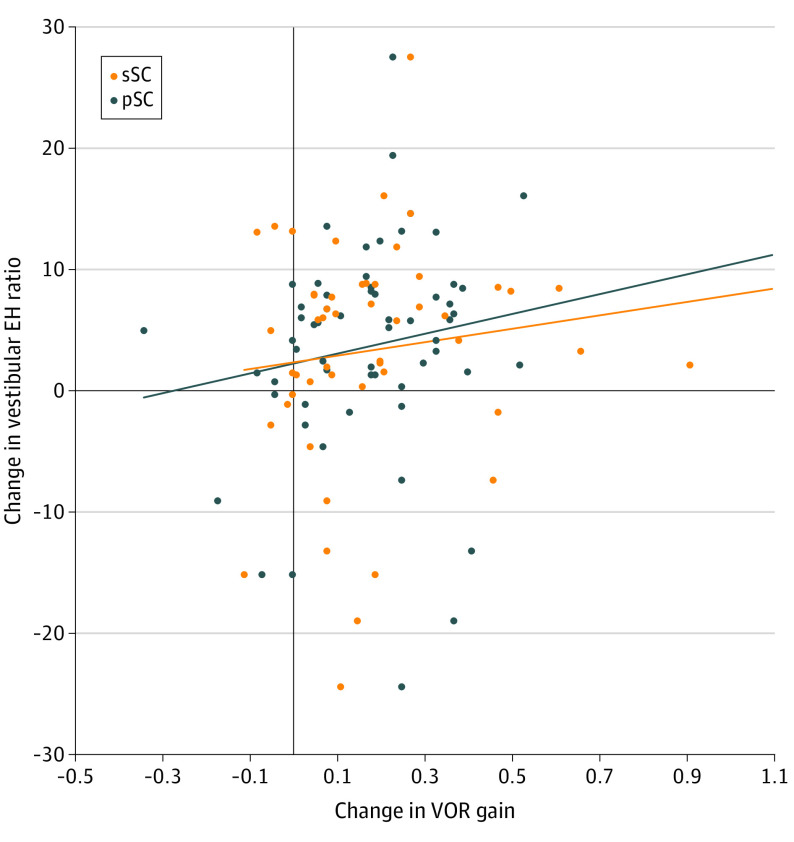

The changes in the frequency of vertiginous episodes per month and the thresholds of hearing levels are shown in Figure 2C and Figure 2D. The frequency of the mean number of vertiginous episodes per month decreased from 2.9 episodes at the first examination to 0.8 episodes at 24 months, for a difference of 2.1 episodes (95% CI, 0.7-3.6 episodes). Each mean number of episodes was 2.9 episodes at the first examination and 0.8 episodes at 24 months (effect size, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.02-0.27). (Figure 2C). The mean hearing level increased from 40.9 dB to 44.5 dB, for a difference of 3.5 dB (95% CI, 0.7-6.4 dB). Each mean hearing level was 40.9 dB at the first examination and 44.5 dB at 24 months (effect size, 0.06 dB; 95% CI, 0-0.13 dB). (Figure 2D). The association between the change in VOR gain and the change in the vestibular endolymphatic hydrops volume ratio in the vertical semicircular canals over the 2-year study period is shown in Figure 3. The Pearson correlation coefficients were 0.12 (95% CI, −0.16 to 0.38) for the superior semicircular canal and 0.16 (95% CI, −0.11 to 0.41) for the posterior semicircular canal.

Figure 3. Scatter Diagram of Association Between Change in Vestibuloocular Reflex Gain and Change in Ratio of Vestibular Endolymphatic Hydrops Volume.

EH indicates endolymphatic hydrops; pSC, posterior semicircular canal; sSC, superior semicircular canal; and VOR, vestibuloocular reflex.

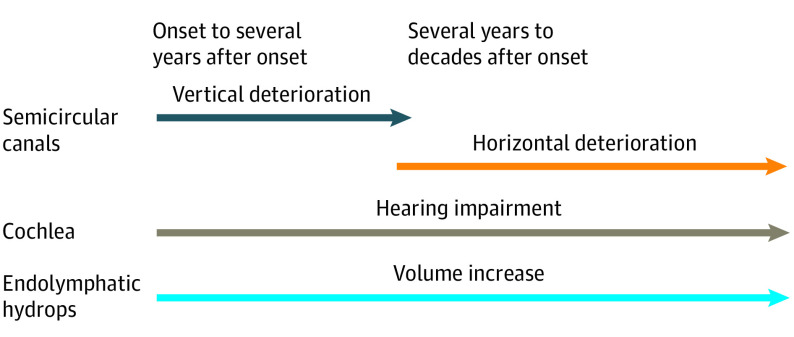

When the cohort was divided into 2 age groups (<60 years and ≥60 years, with the cutoff age of 60 years chosen because it was the median age) to assess the association between age and decreases in VOR gain in the vertical semicircular canals, we found that the effect size was higher in the older group (n = 28) than in the younger group (n = 27). For the posterior semicircular canal, the effect size was 0.53 in the older group compared with 0.24 in the younger group; for the superior semicircular canal, the effect size was 0.37 in the older group compared with 0.31 in the younger group. The pathophysiological progression during the course of Ménière disease is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Pathophysiological Progression of Ménière Disease.

Discussion

In the present study, we prospectively investigated vHIT findings for all semicircular canals and caloric test responses in patients with Ménière disease for 2 years. In previous studies, vestibular function in patients with Ménière disease has most often been evaluated using caloric testing, and caloric response has been reported to gradually decrease over time.1 However, patients with Ménière disease can have normal vHIT results despite worse or absent caloric test results.6,7,8 A previous cross-sectional study indicated that abnormal vHIT findings in patients with Ménière disease are most frequently found in the posterior semicircular canal rather than the horizontal semicircular canal.2 The study suggested that evaluating head impulses only horizontally is insufficient to fully evaluate canal function in patients with Ménière disease. Instead, to accurately assess canal function in these patients, it is necessary to evaluate all semicircular canals quantitatively using vHITs.

In the present study, we observed that the VOR gain in the vertical semicircular canals decreased substantially over the 2-year study period (Figure 1A and Figure 1B), while the VOR gain in the horizontal semicircular canal was maintained in both canal tests (Figure 1C and Figure 1D). These contrasting results suggest that deterioration in the vertical semicircular canals precedes deterioration in the horizontal semicircular canal in the early stage of Ménière disease, implying that the horizontal semicircular canal is more stable; however, the VOR gain in the horizontal semicircular canal may also decrease after several years, according to a survival plot of vHIT results of all semicircular canals.16 The present findings principally apply to the early stage of Ménière disease because the disease duration among participants in this study was less than 4 years in more than 70% of patients (Table).

An important finding of the present study is that the function of the semicircular canals, especially that of the vertical semicircular canals, consistently decreases during the early stage of Ménière disease. We observed a simultaneous decrease in the frequency of vertiginous episodes, but this decrease in frequency does not necessarily imply an improvement in semicircular canal function. Thus, the receipt of medication may ameliorate subjective vertiginous symptoms but may not restore semicircular canal dysfunction because improvements could be associated with a placebo effect,17 as medication receipt has not been associated with improvements in etiological mechanisms. Because preexisting dysfunction of the semicircular canals might persist, clinicians may need to be more conservative when using an ablative procedure on the contralateral ear, even after vertiginous symptoms have resolved.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated whether the characteristics of vertiginous sensation in patients with Ménière disease change over time and whether the progression of vertical semicircular canal dysfunction may be associated with a subjective sensation of rotatory vertigo rather than dizziness when episodes of vertigo occur. Aging has been reported to impair semicircular canal function18 and vertical head movement.19 When the present cohort was divided into 2 age groups to assess the association between age and decreases in VOR gain in the vertical semicircular canals, the effect size was higher in the older group than the younger group. Thus, older patients with Ménière disease may be more susceptible to the consequences of semicircular canal dysfunction.

The extent to which endolymphatic hydrops volume is associated with VOR gain in the vertical semicircular canals is unknown. Endolymphatic hydrops volume is associated with caloric response as a modifying factor in patients with Ménière disease,2 and endolymphatic hydrops volume is also associated with deterioration in hearing function during medical treatment for Ménière disease.5 One study reported that, based on MRI results, endolymphatic hydrops in the semicircular canals was distributed more dominantly in the superior and posterior semicircular canals than in the horizontal semicircular canal over time.20 This progressive endolymphatic hydrops distribution within the semicircular canals might have implications for VOR gain in the vertical semicircular canals. Therefore, we longitudinally evaluated the endolymphatic hydrops volume change and examined whether this change was associated with the change in VOR gain. In the present study, vestibular endolymphatic hydrops volume increased substantially over the 2-year study period, which was similar to the results of a previous preliminary study5 (Figure 2A and Figure 2B). Regarding clinical symptoms of Ménière disease, the frequency of vertiginous episodes decreased substantially, and hearing function decreased slightly in this cohort (Figure 2C and Figure 2D).

In contrast to the accepted practice of approaching the initial medical management of Ménière disease with the aim of reducing endolymphatic hydrops volume, the present study found that endolymphatic hydrops developed longitudinally despite medical treatment, including treatment with diuretic therapy, which was consistent with the findings of a previous study.5 These results indicate that endolymphatic hydrops, the underlying pathological feature of Ménière disease, can develop for at least a certain period in the chronic course of Ménière disease. However, this finding does not necessarily suggest that endolymphatic hydrops and physical findings are not associated. We hypothesize that endolymphatic hydrops volume reflects the sum of cochlear and vestibular symptom activities (eg, worsening of hearing and frequency of vertiginous episodes) but is more likely to be associated with cochlear symptoms. A previous study reported that endolymphatic hydrops volume was not associated with maximum slow-phase velocity, whereas pure-tone audiometric results and endolymphatic hydrops volume were associated,5 and the same association was found among the larger cohort included in the present study. This finding suggests that cochlear symptoms are more likely to be reflected in endolymphatic hydrops volume. In the present study, vertiginous symptoms decreased during the period of medication receipt, but hearing function worsened, suggesting a cochlear association with endolymphatic hydrops volume. We cannot draw conclusions regarding the association of vestibular migraine with vertiginous symptoms because patients with vestibular migraine were excluded in the present study.

The scatter diagram in Figure 3 indicates an association between change in the vestibular endolymphatic hydrops volume ratio and change in VOR gain in the vertical semicircular canals; however, this association is not substantial, which suggests that endolymphatic hydrops enlargement is not associated with vertical semicircular canal dysfunction. An unknown disorder, other than endolymphatic hydrops, might be associated with the rate of deterioration in the vertical semicircular canals, but this disorder is not likely to be neurological because the afferent superior vestibular nerve dominates in both the horizontal and superior semicircular canals. For example, Slitrk6-deficient mice have low vertical VOR gains and normal horizontal VOR gains with hearing loss.21 These similar phenotypes suggest a genetic association with the deterioration in the vertical semicircular canals among patients with Ménière disease. Given that the posterior semicircular canal had the highest prevalence of abnormal vHIT results in a previous study,2 vascular disorders might alternatively be associated with deterioration in the vertical semicircular canals. Vascular ischemia, if it occurs in the vestibulocochlear artery, may be associated with the function of the cochlea, saccule, and posterior semicircular canal. Animal studies have reported that inner ear ischemia is associated with balance dysfunction by inducing the degeneration of hair cells in the vestibule.22 A previous study reported stability of endolymphatic hydrops in patients with Ménière disease during and after episodes of vertigo,13 which suggests there is unlikely to be an ion channel disorder23 involving a local increase in perilymphatic potassium that would induce toxic effects in hair cells.

The present findings have expanded our understanding of pathophysiological characteristics during the early stage of Ménière disease (Figure 4). Regarding canal function, the vertical semicircular canals were found to deteriorate in the first few years, which was followed by deterioration in the horizontal semicircular canal over several years to several decades. With regard to cochlear function, hearing levels decreased over time, and this decrease was approximately proportional to the increase in endolymphatic hydrops volume.5 The frequency of episodes of vertigo decreased, but endolymphatic hydrops gradually developed, although it was reversible, depending on the clinical status of the disease.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the study period was long enough to detect differences in vHIT findings between the horizontal semicircular canal and the vertical semicircular canals; however, our observation period was only 2 years. Ménière disease is a chronic disease with a varying course of vestibular symptoms; therefore, a longer study may further clarify the stability of the horizontal semicircular canal. We have unpublished data that indicate that maximum slow-phase velocity in the affected horizontal semicircular canal decreases during a third year of observation.

Second, the present study did not assess the vestibular function of the saccule and utricle using vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials. Otolith disorders can be diagnosed only through vestibular-evoked myogenic potential testing; therefore, this testing would be necessary to fully characterize inner ear function in patients with Ménière disease. We plan to address this limitation in a future study.

Third, we used total vestibular volume, including the volume in all semicircular canals, to assess the association of endolymphatic hydrops volume change with vertical VOR gains. It is reasonable to separately assess the volumes in the horizontal and vertical semicircular canals; however, the measurement of small volumes is not accurate because of deviations in the images created by slight movements during the scanning procedure. Therefore, we used the total vestibular volume, which is stable and reliable.

Conclusions

In the present study, we prospectively assessed all semicircular canals and endolymphatic hydrops volumes among 55 patients with Ménière disease over a 2-year period. We found that VOR gain in the vertical semicircular canals decreased, while VOR gain in the horizontal semicircular canal was maintained. We also found that the vestibular endolymphatic hydrops volume ratio increased longitudinally, although the frequency of vertiginous episodes decreased during receipt of diuretic therapy. The findings of this observational study provide an expanded understanding of the pathophysiological progression of Ménière disease during the early stage.

References

- 1.Huppert D, Strupp M, Brandt T. Long-term course of Ménière’s disease revisited. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130(6):644-651. doi: 10.3109/00016480903382808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukushima M, Oya R, Nozaki K, et al. Vertical head impulse and caloric are complementary but react opposite to Ménière’s disease hydrops. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(7):1660-1666. doi: 10.1002/lary.27580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamakawa K. Uber die pathologische Veranderung bei einem Ménière-Kraken. J Otolaryngol Jpn. 1938;44:2310-2312. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallpike CS, Cairns H. Observations on the pathology of Ménière’s syndrome: (section of otology). Proc R Soc Med. 1938;31(11):1317-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukushima M, Kitahara T, Oya R, et al. Longitudinal up-regulation of endolymphatic hydrops in patients with Ménière’s disease during medical treatment. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2(6):344-350. doi: 10.1002/lio2.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez N, Rama-Lopez J. Head-impulse and caloric tests in patients with dizziness. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24(6):913-917. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200311000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin F, Simon F, Verillaud B, Herman P, Kania R, Hautefort C. Comparison of video head impulse test and caloric reflex test in advanced unilateral definite Ménière’s disease. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018;135(3):167-169. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hannigan IP, Welgampola MS, Watson SRD. Dissociation of caloric and head impulse tests: a marker of Ménière’s disease. J Neurol. Published online June 20, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09431-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGarvie LA, Curthoys IS, MacDougall HG, Halmagyi GM. What does the dissociation between the results of video head impulse versus caloric testing reveal about the vestibular dysfunction in Ménière’s disease? Acta Otolaryngol. 2015;135(9):859-865. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2015.1015606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi JE, Kim Y-K, Cho YS, et al. Morphological correlation between caloric tests and vestibular hydrops in Ménière’s disease using intravenous Gd enhanced inner ear MRI. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0188301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naganawa S, Yamazaki M, Kawai H, Bokura K, Sone M, Nakashima T. Imaging of Ménière’s disease after intravenous administration of single-dose gadodiamide: utility of subtraction images with different inversion time. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2012;11(3):213-219. doi: 10.2463/mrms.11.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Ménière’s disease. American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Foundation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113(3):181-185. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70102-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukushima M, Akahani S, Inohara H, Takeda N. Stability of endolymphatic hydrops in Ménière disease shown by 3-tesla magnetic resonance imaging during and after vertigo attacks. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(6):583-585. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on Equilibrium. Committee on Equilibrium guidelines for standardization of equilibrium function test. Equilib Res. 2016;75(4):241-245. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naganawa S, Yamazaki M, Kawai H, Bokura K, Sone M, Nakashima T. Imaging of Ménière’s disease after intravenous administration of single-dose gadodiamide: utility of multiplication of MR cisternography and HYDROPS image. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2013;12(1):63-68. doi: 10.2463/mrms.2012-0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zulueta-Santos C, Lujan B, Manrique-Huarte R, Perez-Fernandez N. The vestibulo-ocular reflex assessment in patients with Ménière’s disease: examining all semicircular canals. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014;134(11):1128-1133. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2014.919405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward B, Wettstein V, Golding J, et al. Patient perceptions of effectiveness in treatments for Ménière’s disease: a national survey in Italy. J Int Adv Otol. 2019;15(1):112-117. doi: 10.5152/iao.2019.5758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal Y, Zuniga MG, Davalos-Bichara M, et al. Decline in semicircular canal and otolith function with age. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33(5):832-839. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182545061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schubert MC, Herdman SJ, Tusa RJ. Vertical dynamic visual acuity in normal subjects and patients with vestibular hypofunction. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23(3):372-377. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200205000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiorino F, Pizzini FB, Beltramello A, Barbieri F. Progression of endolymphatic hydrops in Ménière’s disease as evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(7):1152-1157. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31822a1ce2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumoto Y, Katayama K, Okamoto T, et al. Impaired auditory-vestibular functions and behavioral abnormalities of Slitrk6-deficient mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizutari K, Fujioka M, Nakagawa S, Fujii M, Ogawa K, Matsunaga T. Balance dysfunction resulting from acute inner ear energy failure is caused primarily by vestibular hair cell damage. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88(6):1262-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baloh RW. Neurotology of migraine. Headache. 1997;37(10):615-621. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1997.3710615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]