Abstract

Fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs) are fatty acid‐derived molecules and serve as an important form of biodiesel. The oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica is considered an ideal host platform for the production of fatty acid‐derived products due to its excellent lipid accumulation capacity. In this proof‐of‐principle study, several metabolic engineering strategies were applied for the overproduction of FAEE biodiesel in Y. lipolytica. Here, chromosome‐based co‐overexpression of two heterologous genes, namely, PDC1 (encoding pyruvate decarboxylase) and ADH1 (encoding alcohol dehydrogenase) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and the endogenous GAPDH (encoding glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase) gene of Y. lipolytica resulted in successful biosynthesis of ethanol at 70.8 mg/L in Y. lipolytica. The engineered Y. lipolytica strain expressing the ethanol synthetic pathway together with a heterologous wax ester synthase (MhWS) exhibited the highest FAEE titer of 360.8 mg/L, which is 3.8‐fold higher than that of the control strain when 2% exogenous ethanol was added to the culture medium of Y. lipolytica. Furthermore, a synthetic microbial consortium comprising an engineered Y. lipolytica strain that heterologously expressed MhWS and a S. cerevisiae strain that could provide ethanol as a substrate for the production of the final product in the final engineered Y. lipolytica strain was created in this study. Finally, this synthetic consortium produced FAEE biodiesel at a titer of 4.8 mg/L under the optimum coculture conditions.

Keywords: biodiesel, biosynthesis, coculture, FAEE, metabolic engineering, Y. lipolytica

Several metabolic engineering strategies were successfully applied in this study towards direct fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEE) overproduction in the nonconventional oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Additionally, we examined the performance of a microbial consortium for its potential application in FAEE production. The results obtained in this work lay the foundation for future development of more efficient yeast cell factories for the sustainable production of FAEE biodiesel.

Abbreviations

- FAEE

fatty acid ethyl esters

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- GC/MS

gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

- LB

Luria–Bertani

- OD600

optical density at 600 nm

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PDC

pyruvate decarboxylase

- TCA cycle

tricarboxylic acid cycle

- YPD

yeast extract–peptone–dextrose

1. INTRODUCTION

Currently, the demand for renewable and sustainable energy is rapidly increasing. Biodiesel is an important sustainable energy source, and fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs), popularly known as “biodiesel,” can serve as important alternative industrial diesel fuels. In the current global biodiesel market, most commercially available FAEEs are produced via a transesterification reaction between ethanol and various lipid feedstocks, such as plant oils or animal fats, in the presence of a catalyst (Dunn, Ngo, & Haas, 2015; Santana, Tortola, Reis, Silva, & Taranto, 2016; Suppalakpanya, Ratanawilai, & Tongurai, 2010). However, the major problems associated with this chemical synthesis method include the restricted availability of lipid sources and the risk of environmental pollution. In recent years, the use of genetically engineered microorganisms has provided a sustainable and environmentally friendly bioroute for the production of value‐added products, including biofuels, biochemicals, and other bioactive compounds (Cheon, Kim, Gustavsson, & Lee, 2016; Lee, Chou, Ham, Lee, & Keasling, 2008; Mao, Liu, Sun, & Lee, 2017; Marienhagen & Bott, 2013; Yu, Pratomo Juwono, Leong, & Chang, 2014).

The well‐known oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica, which can accumulate lipids at high amounts (Back, Rossignol, Krier, Nicaud, & Dhulster, 2016; Katre, Ajmera, Zinjarde, & Ravikumar, 2017), efficiently utilize a variety of low‐cost hydrophobic substrates for growth (Beopoulos, Chardot, & Nicaud, 2009; Fickers et al., 2010; Lopes, Gomes, Silva, & Belo, 2018), and produce various industrial enzymes and chemicals (Bankar, Kumar, & Zinjarde, 2009; Darvishi, Ariana, Marella, & Borodina, 2018; Ryu, Hipp, & Trinh, 2015; Yan et al., 2018; Zhu & Jackson, 2015), is fast becoming a promising microbial platform for various industrial applications. Moreover, recently, various molecular genetic tools and techniques have been designed and optimized to facilitate the genetic manipulation of Y. lipolytica (Holkenbrink et al., 2018; Schwartz, Hussain, Blenner, & Wheeldon, 2016; Wang, Hung, & Tsai, 2011; Yu et al., 2016) making this oleaginous yeast an ideal host for the engineering of high‐level production of fatty acid‐derived biofuels and biochemicals.

Escherichia coli was the first genetically engineered microorganism used for FAEE production, which was achieved by coexpression of the pyruvate decarboxylase gene and alcohol dehydrogenase gene from Zymomonas mobilis and the atfA gene encoding WS/DGAT (wax ester synthase/acyl‐coenzyme A: diacylglycerol acyltransferase) from Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 (Kalscheuer, Stölting, & Steinbüchel, 2006). Further study revealed high wax ester synthase activity in E. coli with an enzyme from Marinobacter aquaeolei VT8 (MaWS1) from five tested WS/DGAT enzymes from four different bacteria, namely, M. aquaeolei VT8, A. baylyi ATCC 33305, Rhodococcus jostii RHA1, and Psychrobacter cryohalolentis K5. Thus, the WS from M. aquaeolei VT8 (MaWS1) showed the greatest potential for the heterologous production of wax esters and FAEEs in microbes (Barney, Wahlen, Garner, Wei, & Seefeldt, 2012). Moreover, the production of FAEEs by engineered E. coli cell factories was further enhanced upon adopting several metabolic engineering strategies and synthetic biology tools (Steen et al., 2010; Wierzbicki, Niraula, Yarrabothula, Layton, & Trinh, 2016).

To date, most studies have focused on metabolic engineering of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae for FAEE production because the intracellular synthesis of FAEEs in S. cerevisiae can be easily achieved by heterologous expression of WS/DGAT using endogenously produced ethanol and fatty acyl‐CoA (or free fatty acids) as substrates (de Jong, Siewers, & Nielsen, 2016; Nielsen & Shi, 2020; Shi, Valle‐Rodríguez, Khoomrung, Siewers, & Nielsen, 2012; Shi, Valle‐Rodríguez, Siewers, & Nielsen, 2014; Thompson & Trinh, 2015; Valle‐Rodríguez, Shi, Siewers, & Nielsen, 2014; Yu, Jung, Kim, Park, & Han, 2012). It has also been proven that several wax ester synthases from different organisms, including A. baylyi ADP1, Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus DSM 8798, Rhodococcus opacus PD630, Mus musculus C57BL/6, and Psychrobacter arcticus 273‐4, exhibit specific ester synthase activities, leading to the formation of FAEEs in S. cerevisiae. Of these enzymes, a wax ester synthase from M. hydrocarbonoclasticus DSM 8798 was found to be the best one for FAEE production (Shi et al., 2012).

However, in S. cerevisiae, the reported FAEE yield by heterologous expression of a wax ester synthase remains rather low because the production of FAEEs is greatly limited by the small pool of fatty acyl‐CoA and/or free fatty acids (Valle‐Rodríguez et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2012). Compared to the previously used E. coli and S. cerevisiae systems, the oleaginous yeast Y. lipolytica has outstanding lipid accumulation capacity. Thus, abundant intracellular fatty acyl‐CoA (or free fatty acids) is available for the production of FAEEs and other fatty acid‐derived bioproducts through this host's metabolic system (Abghari & Chen, 2014, 2017; Mlíčková et al., 2004; Tai & Stephanopoulos, 2013).

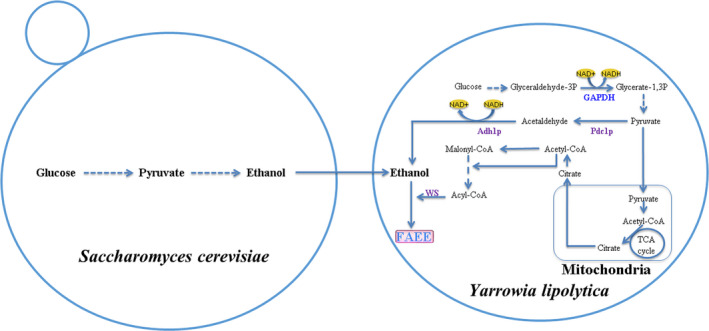

Xu, Qiao, Ahn, and Stephanopoulos (2016) demonstrated the construction of an engineered Y. lipolytica strain for FAEE production through the expression of A. baylyi ADP1 targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum and peroxisome. To our knowledge, this was the first report of FAEE production in Y. lipolytica using metabolic engineering strategies. Gao et al. (2018) further optimized FAEE production in Y. lipolytica through extensive metabolic engineering, and increased FAEE titer was achieved in Y. lipolytica with the addition of exogenous ethanol. Very recently, Ng et al. (2020) demonstrated the production of FAEEs from vegetable cooking oil as a model food waste in the engineered Y. lipolytica. In this small number of studies conducted to date, the FAEE titers obtained with engineered Y. lipolytica strains were low. In this work, we aimed to test the usefulness of new strategies by optimizing FAEE production from endogenously produced ethanol in Y. lipolytica and by cocultivation of an ethanol producer with Y. lipolytica. Finally, engineered Y. lipolytica strain was shown to be capable of producing FAEEs using endogenously produced ethanol. As shown in Figure 1, FAEEs can be generated from ethanol and fatty acyl‐CoA by expressing heterologous WS in our engineered yeast strains. Besides, we demonstrated that a coculture system consisting of the yeasts Y. lipolytica and S. cerevisiae has potential applications in the sustainable production of FAEEs.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram summarizing metabolic engineering strategies for fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEE) production in engineered Yarrowia lipolytica using monoculture and coculture cultivation. The reconstructed biosynthesis pathway for endogenous ethanol production was constructed in Y. lipolytica Po1g via co‐overexpression of two heterologous enzymes pyruvate decarboxylase (Pdc1p) and alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh1p) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C, one native glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) from Y. lipolytica Po1g for NADH regeneration. Wax ester synthases from Marinobacter aquaeolei VT8 (MaWS1) and Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus DSM 8798 (MhWS) were then introduced into Y. lipolytica, respectively, for FAEE production in the monoculture of Y. lipolytica. Homologous and heterologous enzymes are shown in blue and purple, respectively. Solid lines indicate the single‐step reactions of FAEE synthesis in Y. lipolytica, and the multi‐step reaction is shown with the dashed line. The FAEE titers in the engineered Y. lipolytica strains could be further improved when cocultured with the yeast S. cerevisiae that could provide ethanol as a substrate for FAEE production

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Strains, media, and culture conditions

The E. coli strain TOP10 was used as the host in this study for the cloning and propagation of plasmids. E. coli strains carrying recombinant plasmids were routinely cultured at 37°C in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth containing 1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% sodium chloride or on LB agar plates supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin. The Y. lipolytica strain Po1g, a leucine‐auxotrophic derivative of the wild‐type strain W29 (ATCC 20460), was chosen as a host organism for heterologous gene expression in this study. A yeast coculture of the S. cerevisiae strain S288C and the engineered Y. lipolytica strain was designed and developed in this study for the direct production of FAEEs. Routine cultivation of the Y. lipolytica strains, S. cerevisiae strains, and yeast coculture was carried out at 30°C in yeast extract–peptone–dextrose (YPD) liquid medium containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose or on YPD agar plates. Synthetic complete medium lacking leucine (YNBleu) and containing 2% glucose and 0.67% yeast nitrogen base w/o amino acids was used for the selection of Y. lipolytica Leu+ transformants. The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sources and characteristics of strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties or genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Yarrowia lipolytica Po1g | MatA, leu2‐270, ura3‐302::URA3, xpr2‐332, axp‐2 | Madzak, Tréton, and Blanchin‐Roland (2000) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C | MATα, SUC2, gal2, mal2, mel, flo1, flo8‐1, hap1, ho, bio1, bio6 | Mortimer and Johnston (1986) |

| Escherichia coli TOP10 | F‐mcrA, ∆(mrr‐hsdRMS‐mcrBC), Φ80lacZ ∆M15, ∆lacX74, recA1, araD139, ∆(ara‐leu)7697, galU, galK, rpsL, endA1, nupG | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

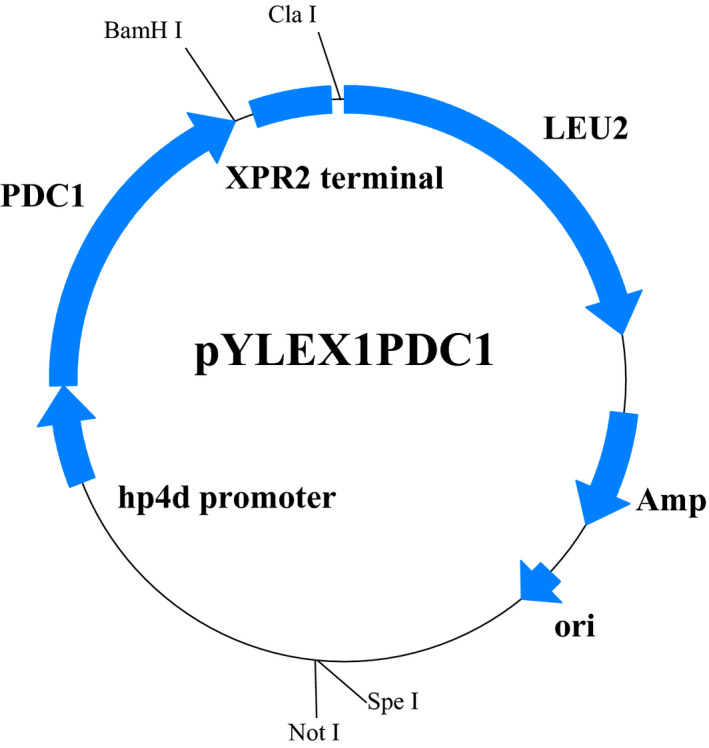

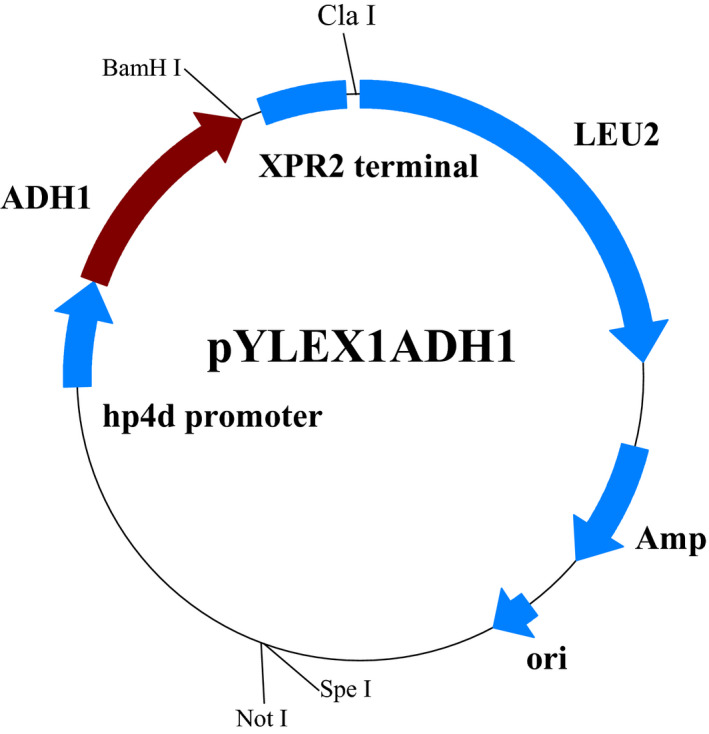

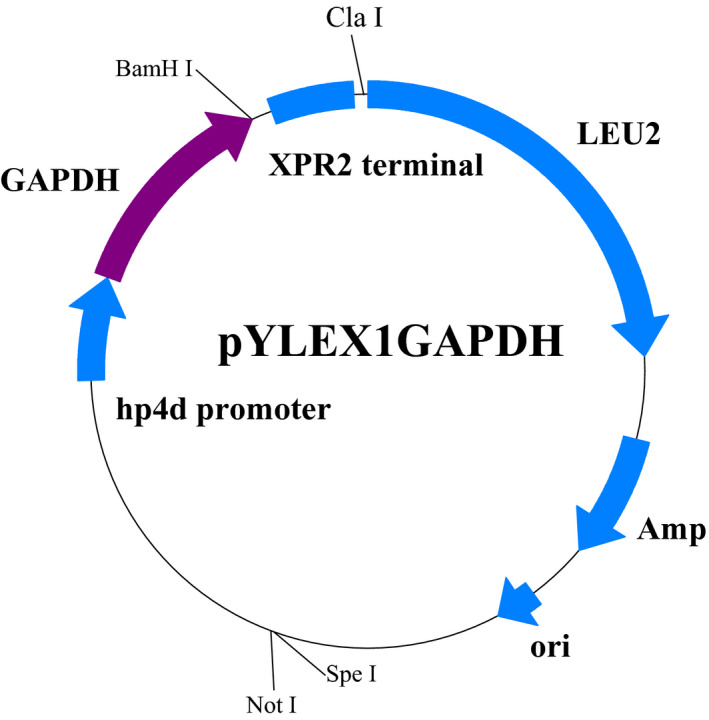

| pYLEX1 | hp4d promoter, XPR2 terminator, LEU2 marker, inserted into the genome at the pBR docking platform of Po1g strain. | Yeastern Biotech |

| pYLEX1PDC1 | pYLEX1 carrying S. cerevisiae S288C pyruvate decarboxylase gene PDC1 | This study |

| pYLEX1ADH1 | pYLEX1 carrying S. cerevisiae S288C alcohol dehydrogenase gene ADH1 | This study |

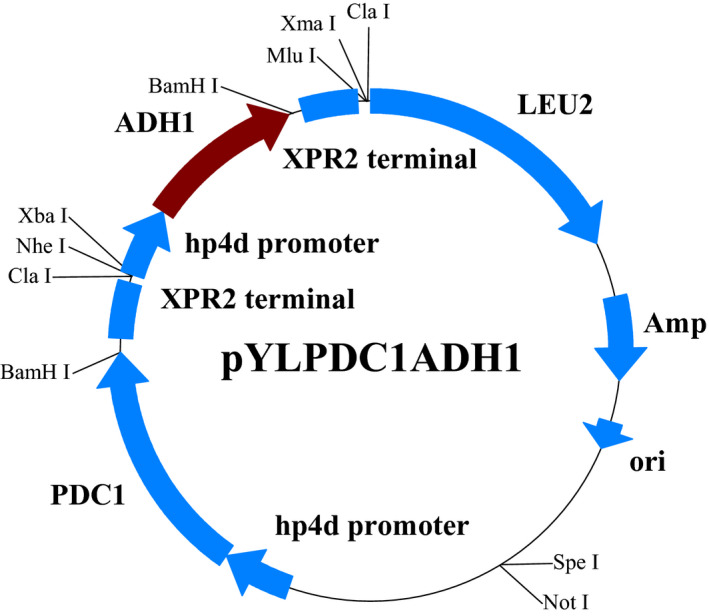

| pYLPDC1ADH1 | pYLEX1 carrying PDC1 and ADH1 | This study |

| pYLEX1GAPDH | pYLEX1 carrying Y. lipolytica Po1g glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase gene GAPDH | This study |

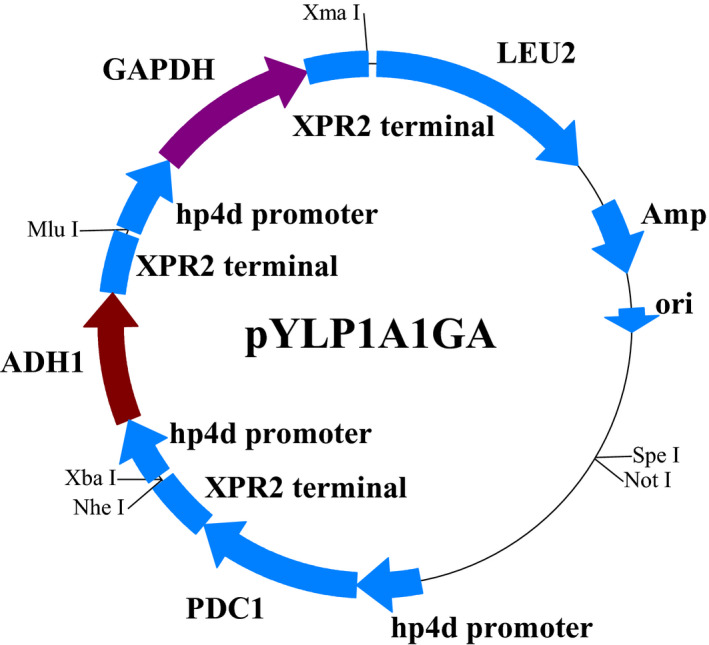

| pYLP1A1GA | pYLEX1 carrying PDC1, ADH1 and GAPDH | This study |

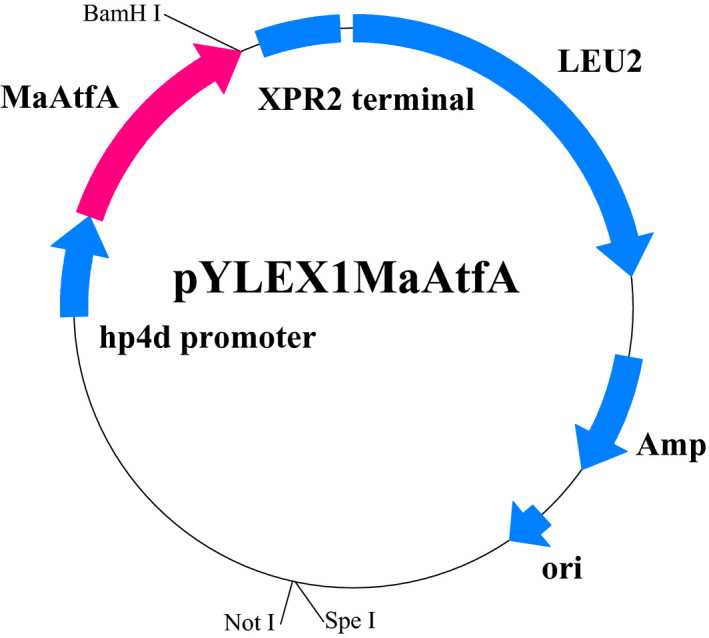

| pYLEX1MaAtfA | pYLEX1 carrying M. aquaeolei VT8 wax ester synthase gene MaAtfA | This study |

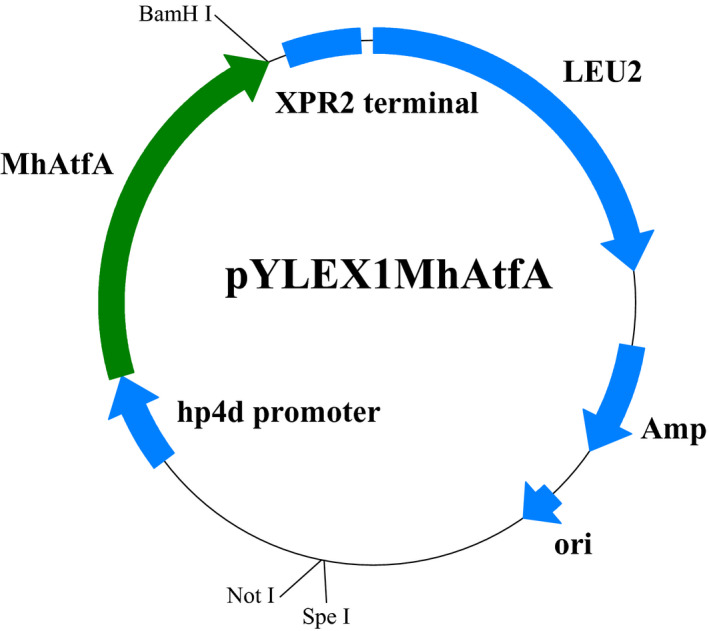

| pYLEX1MhAtfA | pYLEX1 carrying M. hydrocarbonoclasticus DSM 8798 wax ester synthase gene MhAtfA | This study |

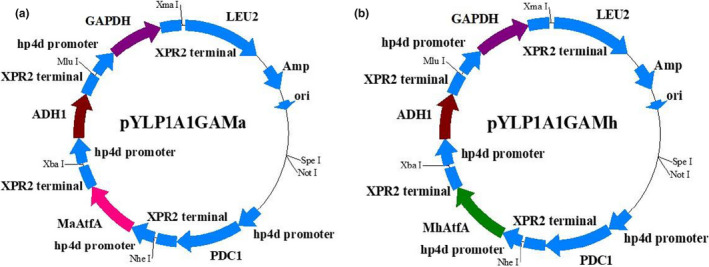

| pYLP1A1GAMa | pYLEX1 carrying PDC1, ADH1, GAPDH and MaAtfA | This study |

| pYLP1A1GAMh | pYLEX1 carrying PDC1, ADH1, GAPDH and MhAtfA | This study |

2.2. DNA manipulation

The plasmid pYLEX1 (Yeastern Biotech, Taipei, Taiwan) containing a strong hybrid promoter (hp4d) was used for gene expression in the Y. lipolytica host strain Po1g. Recombinant plasmids containing different gene expression cassettes were constructed by the following procedures and are graphically depicted in Appendix 1, Figures A1–A8. The PDC1 and ADH1 genes from S. cerevisiae S288C were ligated into the Pml I/BamH I sites of pYLEX1 to yield the plasmids pYLEX1PDC1 and pYLEX1ADH1, respectively (Appendix 1, Figures A1 and A2). The gene expression cassette of ADH1 was amplified by PCR from pYLEX1ADH1 using a forward primer containing Cla I, Nhe I, and Xba I sites and a reverse primer containing Cla I, Xma I, and Mlu I sites, and then ligated into the Cla I site of pYLEX1PDC1 to yield the plasmid pYLPDC1ADH1 (Appendix 1, Figure A3). The native GAPDH gene encoding glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase from Y. lipolytica Po1g was ligated into the Pml I/BamH I sites of pYLEX1 to yield the plasmid pYLEX1GAPDH (Appendix 1, Figure A4). The gene expression cassette of GAPDH was amplified by PCR from pYLEX1GAPDH using a forward primer containing a Mlu I site and a reverse primer containing a Xma I site and then ligated into the Pml I/BamH I sites of pYLPDC1ADH1 to yield the plasmid pYLP1A1GA (Appendix 1, Figure A5). Following the construction of pYLP1A1GA, the wax ester synthase genes MaAtfA from M. aquaeolei VT8 (encoding MaWS1) and MhAtfA from M. hydrocarbonoclasticus DSM 8798 (encoding MhWS) were ligated into the Pml I/BamH I sites of pYLEX1 to yield the plasmids pYLEX1MaAtfA and pYLEX1MhAtfA, respectively (Appendix 1: Figures A6 and A7). The gene expression cassettes of MaAtfA and MhAtfA were amplified by PCR from pYLEX1MaAtfA and pYLEX1MhAtfA and then ligated into the Nhe I/Xba I sites of pYLP1A1GA to yield the plasmids pYLP1A1GAMa and pYLP1A1GAMh (Appendix 1, Figure A8). The primers used for gene cloning and plasmid construction are listed in Appendix 1, Table A1.

2.3. Competent cell preparation and transformation of Y. lipolytica strains

The plasmids pYLEX1, pYLEX1PDC1, pYLEX1ADH1, pYLPDC1ADH1, pYLP1A1GA, pYLEX1MaAtfA, pYLEX1MhAtfA, pYLP1A1GAMa, and pYLP1A1GAMh were first digested with Spe I or Not I, and the resulting fragments were then integrated into the genome of Y. lipolytica Po1g by a chemical transformation process, using a protocol detailed in Appendix 1. The introduced plasmids were integrated at the URA3 locus of strain Po1g. After transformation, the positive Y. lipolytica transformants were selected on YNBleu plates and subsequently confirmed by genomic DNA PCR analysis. Accordingly, the following engineered Y. lipolytica strains were generated through chromosomal integration of the recombinant plasmids in the Y. lipolytica Po1g strain: (a) Po1g::pYLEX1 (used as a negative control strain), (b) Po1g::pYLEX1PDC1, (c) Po1g::pYLEX1ADH1, (d) Po1g::pYLPDC1ADH1, (e) Po1g::pYLP1A1GA, (f) Po1g::pYLEX1MaAtfA, (g) Po1g::pYLEX1MhAtfA, (h) Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMa, and (i) Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh. Five consecutive passages were conducted to evaluate the genetic stability of the genetically engineered Y. lipolytica strains. Subsequently, each strain was subjected to gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis of microbial end products.

2.4. GC/MS analysis of FAEEs and ethanol produced in engineered Y. lipolytica strains

To measure the production of FAEEs and ethanol in engineered Y. lipolytica strains, seed cultures were prepared by inoculating 5 ml of YPD medium in 50‐mL culture tubes with the corresponding strains. The cells were incubated overnight with continuous agitation. Next, 250‐mL flasks containing 50 ml of YPD medium were inoculated with freshly prepared seed cultures to obtain an OD600 of 0.05. All cultures were shaken at 225 rpm and 30°C. Samples were then collected at different time points after the start of cultivation, and a 5‐ml sample of each culture was centrifuged. The growth of the engineered yeast strains was examined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) using a spectrophotometer during the culture period. For the quantification of extracellular ethanol and FAEEs, products were extracted from 2 ml of the culture supernatant (3‐day culture) by vortexing for 2 min with 2 ml of n‐hexane. For the quantification of intracellular ethanol and FAEEs, the cell pellet was lysed by eight rounds of 30‐s bead beating with 1 min of cooling on ice between each round. Following cell lysis, products were extracted by vortexing for 2 min with 2 ml of n‐hexane. The n‐hexane extracts were then analyzed by GC/MS using an HP 7890B GC with an Agilent 5977A MSD equipped with an HP‐FFAP capillary column (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, USA). The GC oven temperature was initially held at 50°C for 1 min and then ramped to 210°C at a rate of 10°C/min and held for 5 min. The temperature was subsequently ramped at 5°C/min to 280°C and held for 5 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas, with an inlet pressure of 13.8 psi. The injector was maintained at 280°C, and the ion source temperature was set to 230°C. FAEE levels were quantified by comparing the integrated peak area of the samples with those of the corresponding standards. Final data analysis was performed using Enhanced Data Analysis software (Agilent, USA).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Construction and characterization of an ethanol synthetic pathway in Y. lipolytica

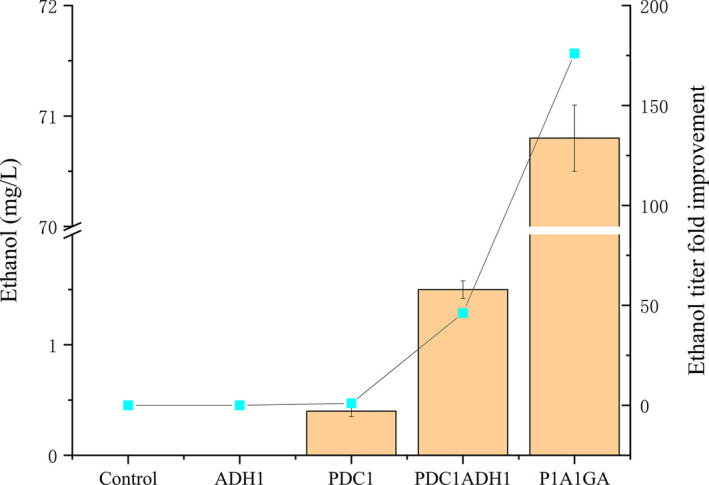

In microorganisms, the production of FAEEs requires two substrates: ethanol and fatty acyl‐CoA (or free fatty acids). Unlike the conventional yeast S. cerevisiae, the unconventional yeast Y. lipolytica does not produce significant ethanol levels (Barth & Gaillardin, 1996). Therefore, to construct a complete pathway for the formation of ethanol from pyruvate in Y. lipolytica, the two genes PDC1 (encoding pyruvate decarboxylase) and ADH1 (encoding alcohol dehydrogenase), which are involved in the ethanol biosynthetic pathway of S. cerevisiae, were selected and subsequently introduced into Y. lipolytica (Figure 1). The engineered Y. lipolytica strain coexpressing the S. cerevisiae PDC1 and ADH1 genes was then tested for ethanol production from glucose. The resulting engineered strain Po1g::pYLEX1‐PDC1ADH1 produced ethanol at a concentration of 1.5 mg/L after 72 hr of cultivation, and no ethanol was detected in the negative control strain Po1g::pYLEX1, demonstrating that the heterologous enzymes encoded by the PDC1 and ADH1 genes that had been integrated into the genome of Y. lipolytica could fulfill their functions in Y. lipolytica. No ethanol was detected in the Po1g::pYLEX1‐ADH1 strain, and the ethanol titer accumulated in the engineered Po1g::pYLEX1‐PDC1 strain (also used as a control) was only 0.4 mg/L (Figure 2). This finding suggests that pyruvate decarboxylases of Y. lipolytica do not have enough activity, carbon flux to the TCA cycle outcompetes PDC activity, or PDC expression is downregulated in glucose medium. Because S. cerevisiae Adh1p catalyzes the reduction of acetaldehyde to ethanol using NADH as the enzyme cofactor, it is proposed that by overexpressing oxidative enzymes that utilize NAD+ as the cofactor, regeneration of NADH can be accelerated, thus providing sufficient supply of NADH for the ethanol–acetaldehyde shuttle, which, in turn, will improve the ability of Y. lipolytica to synthesize ethanol. To this end, the native GAPDH gene encoding a glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase that oxidizes glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate to 1,3‐bisphosphoglycerate in Y. lipolytica (Linck et al., 2014), was chosen for overexpression (Figure 1) because we had previously demonstrated that overexpression of GAPDH can effectively recycle the NADH required for 1‐butanol biosynthesis and thus boost 1‐butanol production in Y. lipolytica (Yu et al., 2018). The titer of ethanol in the resulting engineered strain Po1g::pYLP1A1GA after 72 hr of cultivation increased markedly to 70.8 mg/L, which is a 176.0‐fold increase compared to the titer in the Po1g::pYLEX1‐PDC1 strain and a 46.2‐fold increase compared to the titer in the Po1g::pYLEX1‐PDC1ADH1 strain (Figure 2), and this increase had no significant effects on the cell growth of Y. lipolytica. Thus, our results revealed that the NADH cofactor regeneration strategy could effectively improve ethanol biosynthesis in Y. lipolytica. Interestingly, it was found that ethanol accumulated mainly intracellularly in all of the engineered strains and the extracellular ethanol titer was less than 1 mg/L (at the μg/L level). A possible reason for such a situation is that the resulting ethanol was trapped intracellularly due to the relatively low level of ethanol production. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the successful production of ethanol in the non‐ethanol‐producing yeast Y. lipolytica. However, the ethanol titers obtained in the engineered Y. lipolytica strains are quite low compared to the production of ethanol in the ethanol‐producing yeast S. cerevisiae (Najafpour, Younesi, & Ismail, 2004). Therefore, this heterologous ethanol biosynthetic pathway and the genes that we selected require further optimization to boost the titers.

FIGURE 2.

Production of ethanol by metabolically engineered strains of Yarrowia lipolytica in shake flasks. All the Y. lipolytica strains were cultivated aerobically at 30°C, with vigorous shaking in yeast extract‐peptone‐dextrose medium, and ethanol titers were determined using GC/MS at the 72‐hr time point. Bars represent the corresponding titers attained by different Y. lipolytica strains, and lines represent ethanol titer improvement over PDC1. Control, ADH1, PDC1, PDC1ADH1, and P1A1GA refer to Y. lipolytica Po1g strain carrying integrated plasmids pYLEX1 (empty vector), pYLEX1ADH1, pYLEX1PDC1, pYLPDC1ADH1, and pYLP1A1GA, respectively. All titer values shown represent the averages ± standard deviations of the results of three independent biological replicates

3.2. Integration of the atfA gene, encoding a wax ester synthase, in Y. lipolytica

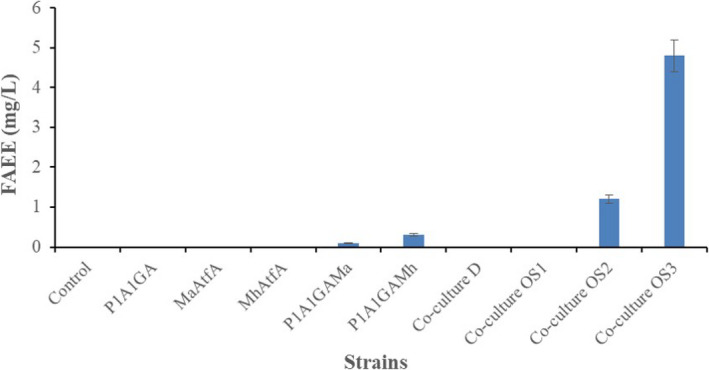

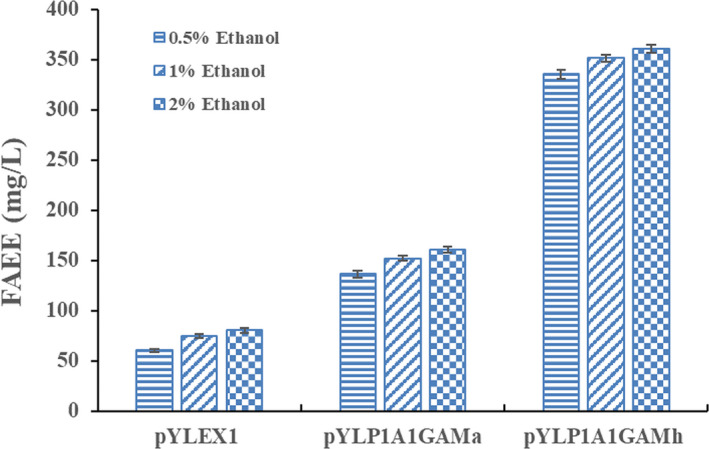

It has been reported that several wax ester synthases can efficiently catalyze the esterification of acyl‐CoA to ethanol to synthesize FAEEs due to their nonspecificity (Barney et al., 2012; Kalscheuer et al., 2006; Steen et al., 2010; Wierzbicki et al., 2016). Thus, we propose that overexpression of wax ester synthase genes in Y. lipolytica could potentially permit the engineered Y. lipolytica strains to increase FAEE production. With the successful construction of ethanol biosynthetic pathways in Y. lipolytica, the esterification enzyme activity that links fatty acyl‐CoA (or fatty acid) to ethanol is required to enable FAEE synthesis in Y. lipolytica (Figure 1). Herein, two wax ester synthases were selected because the heterologous expression of each candidate gene (MaAtfA or MhAtfA) has previously shown great potential for the production of FAEEs in multiple host strains as described in the Introduction section (Barney et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2012; Teo, Ling, Yu, & Chang, 2015). The growth profiles of both engineered strains were similar to that of the parental strain, indicating that integration of multiple expressible heterologous genes into the chromosome of Y. lipolytica did not have any adverse effect on cell growth. After 72 hr of cultivation, FAEEs were produced at a titer of 0.1 and 0.3 mg/L in the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMa strain and Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain, respectively. FAEEs were not detected in any of the remaining seven strains, namely, Po1g::pYLEX1, Po1g::pYLEX1PDC1, Po1g::pYLEX1ADH1, Po1g::pYLPDC1ADH1, Po1g::pYLP1A1GA, Po1g::pYLEX1MaAtfA, and Po1g::pYLEX1MhAtfA (Figure 3). However, the highest titer obtained in FAEE‐producing Y. lipolytica strain (Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh) remained rather low compared to similar examples in the literature on FAEE production in either E. coli or S. cerevisiae (Kalscheuer et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2012). One reason for this discrepancy may be that heterologous expression of either MaAtfA or MhAtfA did not confer adequate FAEE biosynthetic ability to the Y. lipolytica host strain despite the presence of two substrates. Another reason is that the supply of ethanol in the engineered Y. lipolytica strains remained insufficient to meet the demands for high‐level biosynthesis of FAEEs as described above. To verify this hypothesis, the effect of exogenous ethanol was evaluated on the potential for FAEE production in the engineered Y. lipolytica strains. The results showed that FAEE production by the engineered Y. lipolytica strains was greatly enhanced by the addition of exogenous ethanol, as expected (Figure 4). In the presence of 0.5%, 1%, and 2% (v/v) exogenous ethanol, the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMa strain achieved total FAEE titers of 136.4, 152.1, and 160.4 mg/L, respectively, after 72 hr of cultivation, while MhAtfA overexpression led to higher total FAEE titers (335.8, 351.4, 360.8 mg/L) in the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain than in the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMa strain. Interestingly, total FAEE titers of 60.2, 74.8, and 80.3 mg/L (in the presence of 0.5%, 1% and 2% (v/v) exogenous ethanol, respectively) were also observed in the Po1g::pYLEX1 strain which was used as the control strain. This result can be attributed to the esterification activity of endogenous lipases in Y. lipolytica that can catalyze the production of FAEEs (Cao et al., 2017; Matsumoto, Ito, Fukuda, & Kondo, 2004; Meng et al., 2011).

FIGURE 3.

Production of fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs) by the engineered strains of Yarrowia lipolytica and the Y. lipolytica–Sacharomyces cerevisiae coculture. All the yeast strains were cultivated aerobically at 30°C, with vigorous shaking in the yeast extract‐peptone‐dextrose medium. The FAEE titers achieved from the corresponding Y. lipolytica strains were analyzed using GC/MS after 3 days of cultivation, and the FAEE titers achieved from the coculture were analyzed at different time points after the start of cultivation as described in Section 3.3. Control, P1A1GA, MaAtfA, MhAtfA, P1A1GAMa, and P1A1GAMh refer to Y. lipolytica Po1g strain carrying integrated plasmids pYLEX1 (empty vector), pYLP1A1GA, pYLEX1MaAtfA, pYLEX1MhAtfA, pYLP1A1GAMa, and pYLP1A1GAMh, respectively. Co‐culture D, Co‐culture OS1, Co‐culture OS2, and Co‐culture OS3 represent the microbial coculture under the conditions of the original coculture strategy, the first coculture optimization strategy, the second coculture optimization strategy, and the third coculture optimization strategy, respectively, as described in Section 3.3. All titer values shown represent the averages ± standard deviations of the results of three independent biological replicates

FIGURE 4.

Fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEE) production in engineered Yarrowia lipolytica strains expressing wax ester synthases MaWS1 or MhWS supplemented with different concentrations of ethanol. All Y. lipolytica strains were cultivated in YPD medium supplemented with different concentrations (0.5%, 1%, 2%) of ethanol. FAEE titers achieved from the corresponding strains were analyzed using GC/MS after 3 days of cultivation. All titer values shown represent the averages ± standard deviations of the results of three independent biological replicates

A large increase in the FAEE yield was demonstrated for the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMa strain and the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain in the presence of exogenous ethanol as compared to the Po1g::pYLEX1 strain and strains grown in the absence of ethanol. This result indicated that (a) both heterologous enzymes (MaWS1 and MhWS) selected herein could fulfill the roles in catalyzing the formation of FAEEs in Y. lipolytica and that (b) increasing ethanol concentration could boost the production of FAEEs. A higher ethanol concentration was not used because the growth of the corresponding Y. lipolytica strains was greatly affected when the concentration of exogenous ethanol was increased to 3%. The Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain with the highest level of FAEE production (which was 3.8‐fold higher than that of the Po1g::pYLEX1 strain) and with a 1.2‐fold increase in FAEE titer over the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMa strain when fed with 2% ethanol was therefore used for subsequent work in this study. The total FAEEs produced by the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain at an ethanol concentration of 2% contained 10.9% butanoic acid ethyl ester (C4:0), 0.4% decanoic acid ethyl ester (C10:0), 1.2% dodecanoic acid ethyl ester (C12:0), 1.9% myristic acid ethyl ester (C14:0), 56.4% palmitic acid ethyl ester (C16:0), 5.6% palmitoleic acid ethyl ester (C16:1n‐7), 20.2% stearic acid ethyl ester (C18:0), 2.3% oleic acid ethyl ester (C18:1n‐9), and 1.1% linoleic acid ethyl ester (C18:2n‐6), of which palmitic acid ethyl ester, with a sixteen‐carbon saturated fatty acid chain, accounted for more than half of the total FAEE yield. Furthermore, and interestingly, butanoic acid ethyl ester, with a short‐chain fatty acid, accounted for more than 10% of the total yield (Table 2). The phenotype of the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain was considerably stable even after five consecutive passages, indicating high genetic stability.

TABLE 2.

The percentage composition of total FAEEs produced by Yarrowia lipolytica strains under different culture conditions

| Product | Sample 1 (%) | Sample 2 (%) | Sample 3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butanoic acid ethyl ester (C4:0) | 10.9 | 8.6 | BD |

| Decanoic acid ethyl ester (C10:0) | 0.4 | BD | 0.1 |

| Dodecanoic acid ethyl ester (C12:0) | 1.2 | BD | 0.3 |

| Myristic acid ethyl ester (C14:0) | 1.9 | BD | 0.4 |

| Palmitic acid ethyl ester (C16:0) | 56.4 | 51.7 | 25.7 |

| Palmitoleic acid ethyl ester (C16:1n‐7) | 5.6 | 2.6 | 14.1 |

| Stearic acid ethyl ester (C18:0) | 20.2 | 18.1 | 2.9 |

| Oleic acid ethyl ester (C18:1n‐9) | 2.3 | 14.6 | 37.8 |

| Linoleic acid ethyl ester (C18:2n‐6) | 1.1 | 4.4 | 18.7 |

FAEEs produced in shake flasks with YPD media were separated and quantified by GC/MS. All values presented are the mean of three biological replicates. Sample 1 represents the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain fed with a concentration of 2% ethanol as described in Section 3.2. Sample 2 and Sample 3 represent the microbial coculture under the conditions of the second and the third coculture optimization strategies, respectively, as described in Section 3.3. BD represents “below the detection level.”

3.3. FAEE production by cocultivation of the Y. lipolytica Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain and S. cerevisiae S288C strain

As described above, the highest titer of FAEEs achieved in the engineered Y. lipolytica strain was 360.8 mg/L. This titer was much higher than that achieved in the yeast S. cerevisiae harboring the same wax ester synthase from M. hydrocarbonoclasticus DSM 8798 (6.3 mg/L) (Shi et al., 2012). Based on the results obtained here, Y. lipolytica is a more promising candidate yeast species for future applications in FAEE production than S. cerevisiae.

However, ethanol insufficiency is a major bottleneck in the development of Y. lipolytica as a high‐level FAEE producer, and supplying additional ethanol to the culture medium of Y. lipolytica can boost product levels of FAEEs. This finding was confirmed by the results of FAEE production in the Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain when exogenous ethanol was added into the culture medium. Thus, a deeper understanding of the flux throughout the ethanol biosynthetic route in Y. lipolytica is necessary to identify and eliminate the bottlenecks and/or possible competing pathways and, in turn, further improve ethanol accumulation in this oleaginous yeast system.

Instead of further boosting ethanol production in Y. lipolytica through metabolic engineering, which might be a very difficult task, in the present study, we proposed the cocultivation of S. cerevisiae and Y. lipolytica to produce FAEEs in Y. lipolytica using ethanol provided by S. cerevisiae. Many studies have reported the use of microbial coculture systems for direct production of specific target compounds, increasing the production yield, shortening the fermentation time, and/or reducing the process cost and/or realizing some specific function (He, Duan, & Liu, 2014; Hickert, Cunha‐Pereira, Souza‐Cruz, Rosa, & Ayub, 2013; Minty et al., 2013; Singh, Bajar, & Bishnoi, 2014; Zhou, Qiao, Edgar, & Stephanopoulos, 2015). We therefore sought to investigate whether the use of a microbial coculture system could successfully contribute to the production of FAEEs and potentially enhance FAEE fermentation performance by coculturing the S. cerevisiae S288C strain with the engineered Y. lipolytica strain Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh, since S. cerevisiae can metabolize glucose to produce relatively large amounts of ethanol.

To this end, the effect of different coculture designs on FAEE production was investigated using shake‐flask experiments. When seed cultures of S. cerevisiae S288C and Y. lipolytica Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh with the same initial OD600 of 0.05 were simultaneously inoculated into one flask containing YPD medium (the original coculture strategy), we noted that the production yield of FAEEs in the coculture samples was below the detection limit after three days of cultivation, suggesting that this coculture condition is unsuitable for FAEE accumulation in this original mixed microbial culture. Another cause for this effect could be the unsuitable condition for FAEE accumulation in this original mixed microbial culture.

To validate the hypothesis, FAEE production under different coculture conditions was investigated next. The first coculture optimization strategy was as follows: S. cerevisiae S288C was first cultured separately for 24 hr, and then, a fresh overnight seed culture of Y. lipolytica Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh was inoculated at an initial OD600 of 0.2 into the fermentation medium of S. cerevisiae. The coculture sample was collected after 3 days for subsequent GC/MS analysis. Under the conditions of the first coculture strategy, GC/MS analysis results also indicated that FAEEs were not present in the mixed coculture performed by sequential inoculation of S. cerevisiae and Y. lipolytica. The second coculture optimization strategy was as follows: Y. lipolytica Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh was first cultured for 24 hr, and then, fresh overnight seed culture of S. cerevisiae S288C was inoculated at an initial OD600 of 0.2 into the fermentation medium of Y. lipolytica. The coculture sample was collected after 2 days for subsequent GC/MS analysis. Under the conditions of the second coculture strategy, the synthetic consortium produced FAEEs at a titer of 1.2 mg/L (Figure 3). The total FAEEs contained 8.6% butanoic acid ethyl ester (C4:0), 51.7% palmitic acid ethyl ester (C16:0), 2.6% palmitoleic acid ethyl ester (C16:1n‐7), 18.1% stearic acid ethyl ester (C18:0), 14.6% oleic acid ethyl ester (C18:1n‐9), and 4.4% linoleic acid ethyl ester (C18:2n‐6). Also, the concentrations of decanoic acid ethyl ester, dodecanoic acid ethyl ester, and myristic acid ethyl ester decreased to below the detection limit, unlike the concentrations in Y. lipolytica (Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain) alone (Table 2). The third coculture optimization strategy was as follows: S. cerevisiae S288C and Y. lipolytica Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh were cultured separately for 24 hr with continuous shaking in YPD medium, and then, 25 ml of a 24 hr inoculum of each was transferred into a new flask and incubated for an additional 48 hr. Under the conditions of the third coculture strategy, this synthetic consortium produced FAEEs at a titer of 4.8 mg/L (Figure 3). This titer represents a 3.0‐fold increase compared to the second coculture strategy, which indicates that the third coculture strategy provides the best conditions for the production of FAEEs among the three strategies tested in the present study for the current coculture system. Under this condition, the total FAEEs contained 0.1% decanoic acid ethyl ester (C10:0), 0.3% dodecanoic acid ethyl ester (C12:0), 0.4% myristic acid ethyl ester (C14:0), 25.7% palmitic acid ethyl ester (C16:0), 14.1% palmitoleic acid ethyl ester (C16:1n‐7), 2.9% stearic acid ethyl ester (C18:0), 37.8% oleic acid ethyl ester (C18:1n‐9), and 18.7% linoleic acid ethyl ester (C18:2n‐6) (Table 2). The composition of the FAEEs produced by the Y. lipolytica–S. cerevisiae coculture under this condition was quite different from that in Y. lipolytica (Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh strain) cultured alone at an ethanol concentration of 2% and that obtained from the second coculture optimization strategy. In particular, the concentrations of palmitic acid ethyl ester (C16:0) and stearic acid ethyl ester (C18:1n‐9) decreased significantly, while the concentrations of palmitoleic acid ethyl ester, oleic acid ethyl ester, and linoleic acid ethyl ester, with unsaturated carbon chains, increased substantially. Additionally, the FAEE composition of this mixed microbial culture was dominated by carbon chain lengths of C16 and C18 without detectable amounts of butanoic acid ethyl ester.

Interestingly, the FAEE titer obtained from the two‐yeast‐strain coculture system is lower than that of the single yeast strain Y. lipolytica Po1g::pYLP1A1GAMh fed with exogenous ethanol. We therefore measured ethanol concentrations in coculture systems. Results showed that the ethanol concentrations in coculture systems (180.5, 440.8, 500.4 mg/L for the first, second, and third coculture conditions, respectively) are much lower than 1% (v/v) which was produced in the monoculture of S. cerevisiae. One of the possible reasons for these results may be that the metabolism of two strains changed when they compete for growth resources in one system (Hettich, Sharma, Chourey, & Giannone, 2012; Khan et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2015). However, this aspect needs to be investigated further in future work. Based on these results, we confirmed that the application of this microbial coculture system could be a viable strategy for the sustainable production of FAEEs. With the increasing knowledge, it is believed that this coculture system could be further optimized to result in a significant improvement in FAEE production.

4. CONCLUSIONS

The nonconventional oleaginous yeast Y. lipolytica has previously been shown to be a competitive host organism for the production of fatty acid‐derived products owing to several competitive advantages over other microbial species. In this proof‐of‐principle study, an efficient and eco‐friendly catalytic route for the synthesis of FAEE biodiesel was established in the oleaginous yeast Y. lipolytica through metabolic engineering and the coincubation strategy adopted in this study was also shown to be very promising for future FAEE production. Meanwhile, this study also described the successful biosynthesis of ethanol in metabolically engineered Y. lipolytica. In conclusion, this work demonstrates the feasibility of adopting Y. lipolytica as an engineered cell factory for FAEE production and provides a starting point for advancing the microbe‐based industrial production of FAEE biodiesel, which could be an environmentally friendly and sustainable solution for green fuel (biodiesel) production. However, there remains much room for improvement in the use of Y. lipolytica for the production of FAEEs to reach a commercially acceptable level. First, future efforts should focus on screening novel sources of ester synthase enzymes from vastly different organisms with desirable features such as higher enzyme activity, stability, and specificity when expressed in Y. lipolytica. Second, various novel metabolic engineering strategies for maximizing ethanol biosynthesis and fatty acyl‐CoA (or free fatty acids) biosynthesis as well as further enhancing coproduction of ethanol and fatty acyl‐CoA in the engineered Y. lipolytica strains should be properly designed and applied. Third, strains and culture conditions in the coculture system need to be further optimized to accomplish a marked improvement in the FAEE titer.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Aiqun Yu: Conceptualization (lead); investigation (lead); formal analysis (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal); Yu Zhao, Jian Li, Shenglong Li, Yaru Pang, and Yakun Zhao: Investigation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal); Cuiying Zhang and Dongguang Xiao: Conceptualization (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for funding support by the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin, China (17JCYBJC40800), the Research Foundation of Tianjin Municipal Education Commission, China (2017ZD03), the Innovative Research Team of Tianjin Municipal Education Commission (TD13‐5013), Public Service Platform Project for Selection and Fermentation Technology of Industrial Microorganisms, China (17PTGCCX00190), Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Project (18PTSYJC00140), the Open Fund of Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology and Technology, Nankai University, the Startup Fund for “Haihe Young Scholars” of Tianjin University of Science and Technology, and the Thousand Young Talents Program of Tianjin, China.

APPENDIX 1.

Reagents

iProof high‐fidelity DNA polymerase was purchased from Bio‐Rad Labs (Hercules, CA, USA). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, Taq DNA polymerase, and PCR reagents were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA, USA). CSM‐Leu (complete supplement mixture minus leucine) dropout mixture was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA). Yeast extract and peptone were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Takara Biotechnology (Dalian, Liaoning, China). FAEE standards were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise stated.

Preparation of Y. lipolytica Po1g competent cell

Inoculate a colony of Y. lipolytica Po1g strain from a fresh YPD plate in 10 ml YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, and 50 mM citrate buffer pH 4.0) in a 250‐ml flask. Incubate with shaking at 225 rpm at 30°C for 20 hr.

Pellet the cells by centrifuging 5 min at 5,000 g at room temperature.

Wash the cells with 20 ml TE buffer and pellet the cells similarly as Step 2.

Resuspend the cells in 1 ml of 0.1 M lithium acetate (pH 6.0, adjusted with acetic acid) and incubate for 10 min at room temperature.

Aliquot the competent cells (100 µl) into sterile 1.5‐ml tubes. Proceed to the transformation steps below immediately, or add glycerol to a final concentration of 25% (v/v) and store at −80°C for long‐term storage.

Transformation of Y. lipolytica Po1g cells

Gently mix 10 µl of denatured salmon sperm DNA (10 mg/ml) and 1–5 µg of the linearized plasmid with 100 µl of competent cells, and incubate at 30°C for 15 min.

Add 700 µl of 40% PEG‐4000 (dissolved in 0.1 M lithium acetate pH 6.0), mix well, and incubate at 30°C for 60 min with shaking (225 rpm).

Heat shock the transformation mixture at 39°C for 60 min.

Add 1 ml YPD medium and recover for 2 hr at 30°C and 225 rpm.

Centrifuge at 10,000 g for 1 min, remove supernatant, and resuspend the pellet in 1 ml of TE buffer.

Repellet the cells and discard supernatant again.

Resuspend the pellet in 100 µl of TE buffer and plate onto selective plates (leucine‐deficient plates).

TABLE A1.

Primers used to perform heterologous gene expression in this study

| Primers | Sequences | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5′‐AATGTCTGAAATTACTTTGGG | Cloning PDC1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C into pYLEX1 for the construction of pYLEX1PDC1, forward primer. |

| 2 | 5′‐CGGGATCCTTATTGCTTAGCGTTGGTAG | Cloning PDC1 gene of S. cerevisiae S288C into pYLEX1 for construction of pYLEX1PDC1, reverse primer. |

| 3 | 5′‐AATGTCTATCCCAGAAACTCA | Cloning ADH1 gene of S. cerevisiae S288C into pYLEX1 for construction of pYLEX1ADH1, forward primer. |

| 4 | 5′‐CGGGATCCTTATTTAGAAGTGTCAACAA | Cloning ADH1 gene of S. cerevisiae S288C into pYLEX1 for construction of pYLEX1ADH1, reverse primer. |

| 5 | 5′‐AATGGCCATCAAAGTCGGTAT | Cloning GAPDH gene of Y. lipolytica Po1g into pYLEX1 for construction of pYLEX1GAPDH, forward primer. |

| 6 | 5′‐CGGGATCCCTAAGCGGAAGCATC CTTCT | Cloning GAPDH gene of Y. lipolytica Po1g into pYLEX1 for construction of pYLEX1GAPDH, reverse primer. |

| 7 | 5′‐CCATCGATGCTAGCTCTAGAGCTCTCCCTTATGCGACT | Amplifying ADH1 expression cassette from pYLEX1ADH1 into pYLEX1PDC1 to yield pYLPDC1ADH1, forward primer. |

| 8 | 5′‐CCATCGATCCCGGGACGCGTGAATTCGGACACGGGCAT | Amplifying ADH1 expression cassette from pYLEX1ADH1 into pYLEX1PDC1 to yield pYLPDC1ADH1, reverse primer. |

| 9 | 5′‐CGACGCGTGCTCTCCCTTATGCGACT | Amplifying GAPDH expression cassette from pYLEX1GAPDH into pYLPDC1ADH1 to yield pYLP1A1GA, forward primer. |

| 10 | 5′‐CCCCCGGGGAATTCGGACACGGGCAT | Amplifying GAPDH expression cassette from pYLEX1GAPDH into pYLPDC1ADH1 to yield pYLP1A1GA, reverse primer. |

| 11 | 5′‐AATGACTCCATTGAACCCAAC | Cloning MaAtfA gene of Marinobacter aquaeolei VT8 into pYLEX1 for construction of pYLEX1MaAtfA, forward primer. |

| 12 | 5′‐CGGGATCCTCAGTGATGGTGATGATGATGTAAACCAGCGTTCAATTCCA | Cloning MaAtfA gene of M. aquaeolei VT8 into pYLEX1 for construction of pYLEX1MaAtfA, reverse primer. |

| 13 | 5′‐AATGAAGAGATTGGGTACTTT | Cloning MhAtfA gene of Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus DSM 8798 into pYLEX1 for construction of pYLEX1MhAtfA, forward primer. |

| 14 | 5′‐CGGGATCCTTAGTGATGGTGATGATGATGTTTTCTAGTTCTGGCTCTCT | Cloning MhAtfA gene of M. hydrocarbonoclasticus DSM 8798 into pYLEX1 for construction of pYLEX1MhAtfA, reverse primer. |

| 15 | 5′‐CTAGCTAGCGCTCTCCCTTATGCGACT | Amplifying MaAtfA expression cassette from pYLEX1MaAtfA into pYLP1A1GA to yield pYLP1A1GAMa, forward primer. |

| 16 | 5′‐GCTCTAGAGAATTCGGACACGGGCAT | Amplifying MaAtfA expression cassette from pYLEX1MaAtfA into pYLP1A1GA to yield pYLP1A1GAMa, reverse primer. |

| 17 | 5′‐CTAGCTAGCGCTCTCCCTTATGCGACT | Amplifying MhAtfA expression cassette from pYLEX1MhAtfA into pYLP1A1GA to yield pYLP1A1GAMh, forward primer. |

| 18 | 5′‐GCTCTAGAGAATTCGGACACGGGCAT | Amplifying MhAtfA expression cassette from pYLEX1MhAtfA into pYLP1A1GA to yield pYLP1A1GAMh, reverse primer. |

FIGURE A1.

Map of the plasmid pYLEX1PDC1

FIGURE A2.

Map of the plasmid pYLEX1ADH1

FIGURE A3.

Map of the plasmid pYLPDC1ADH1

FIGURE A4.

Map of the plasmid pYLEX1GAPDH

FIGURE A5.

Map of the plasmid pYLP1A1GA

FIGURE A6.

Map of the plasmid pYLEX1MaAtfA

FIGURE A7.

Map of the plasmid pYLEX1MhAtfA

FIGURE A8.

Representative maps of the plasmid vectors containing gene integration cassettes for expression in Yarrowia lipolytica. The recombinant vector pYLP1A1GAMa (A) which carries genes PDC1, ADH1, GAPDH, and MaAtfA, and the recombinant vector pYLP1A1GAMh (B) which carries genes PDC1, ADH1, GAPDH, and MhAtfA were constructed through multiple rounds of restriction digestion and ligation for overexpressing the entire pathway of FAEE synthesis, respectively

Yu A, Zhao Y, Li J, et al. Sustainable production of FAEE biodiesel using the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica . MicrobiologyOpen. 2020;9:e1051 10.1002/mbo3.1051

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the appendices.

REFERENCES

- Abghari, A. , & Chen, S. (2014). Yarrowia lipolytica as an oleaginous cell factory platform for production of fatty acid‐based biofuel and bioproducts. Frontiers in Energy Research, 2, 21 10.3389/fenrg.2014.00021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abghari, A. , & Chen, S. (2017). Engineering Yarrowia lipolytica for enhanced production of lipid and citric acid. Fermentation, 3(3), 34 10.3390/fermentation3030034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Back, A. , Rossignol, T. , Krier, F. , Nicaud, J. M. , & Dhulster, P. (2016). High‐throughput fermentation screening for the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica with real‐time monitoring of biomass and lipid production. Microbial Cell Factories, 15, 147 10.1186/s12934-016-0546-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankar, A. V. , Kumar, A. R. , & Zinjarde, S. S. (2009). Environmental and industrial applications of Yarrowia lipolytica . Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 84(5), 847–865. 10.1007/s00253-009-2156-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barney, B. M. , Wahlen, B. D. , Garner, E. , Wei, J. , & Seefeldt, L. C. (2012). Differences in substrate specificities of five bacterial wax ester synthases. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78(16), 5734–5745. 10.1128/AEM.00534-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth, G. , & Gaillardin, C. (1996). Yarrowia lipolytica In Wolf K. (Ed.), Nonconventional yeasts in biotechnology: A handbook (pp. 313–380). Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Beopoulos, A. , Chardot, T. , & Nicaud, J. M. (2009). Yarrowia lipolytica: A model and a tool to understand the mechanisms implicated in lipid accumulation. Biochimie, 91(6), 692–696. 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H. , Wang, M. , Deng, L. , Liu, L. , Schwaneberg, U. , Tan, T. , … Nie, K. (2017). Sugar‐improved enzymatic synthesis of biodiesel with Yarrowia lipolytica lipase 2. Energy and Fuels, 31(6), 6248–6256. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b01091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, S. , Kim, H. M. , Gustavsson, M. , & Lee, S. Y. (2016). Recent trends in metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the production of advanced biofuels. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 35, 10–21. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvishi, F. , Ariana, M. , Marella, E. R. , & Borodina, I. (2018). Advances in synthetic biology of oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for producing non‐native chemicals. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 102(14), 5925–5938. 10.1007/s00253-018-9099-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, B. W. , Siewers, V. , & Nielsen, J. (2016). Physiological and transcriptional characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered for production of fatty acid ethyl esters. FEMS Yeast Research, 16(1), fov105 10.1093/femsyr/fov105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, R. O. , Ngo, H. L. , & Haas, M. J. (2015). Branched‐chain fatty acid methyl esters as cold flow improvers for biodiesel. Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society, 92(6), 853–869. 10.1007/s11746-015-2643-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fickers, P. , Benetti, P. H. , Waché, Y. , Marty, A. , Mauersberger, S. , Smit, M. S. , & Nicaud, J. M. (2010). Hydrophobic substrate utilisation by the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica, and its potential applications. FEMS Yeast Research, 5(6–7), 527–543. 10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q. , Cao, X. , Huang, Y. Y. , Yang, J. L. , Chen, J. , Wei, L. J. , & Hua, Q. (2018). Overproduction of fatty acid ethyl esters by the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica through metabolic engineering and process optimization. ACS Synthetic Biology, 7(5), 1371–1380. 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. M. , Duan, X. G. , & Liu, Y. S. (2014). Enhanced bioremediation of oily sludge using co‐culture of specific bacterial and yeast strains. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, 89(11), 1785–1792. 10.1002/jctb.4471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hettich, R. L. , Sharma, R. , Chourey, K. , & Giannone, R. J. (2012). Microbial metaproteomics: Identifying the repertoire of proteins that microorganisms use to compete and cooperate in complex environmental communities. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 15(3), 373–380. 10.1016/j.mib.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickert, L. R. , Cunha‐Pereira, F. D. , Souza‐Cruz, P. B. D. , Rosa, C. A. , & Ayub, M. A. Z. (2013). Ethanogenic fermentation of co‐cultures of Candida shehatae HM 52.2 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae ICV D254 in synthetic medium and rice hull hydrolysate. Bioresource Technology, 131, 508–514. 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.12.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holkenbrink, C. , Dam, M. I. , Kildegaard, K. R. , Beder, J. , Dahlin, J. , Doménech, B. D. , & Borodina, I. (2018). EasyCloneYALI: CRISPR/Cas9‐based synthetic toolbox for engineering of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica . Biotechnology Journal, 13(9), 10.1002/biot.201700543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalscheuer, R. , Stölting, T. , & Steinbüchel, A. (2006). Microdiesel: Escherichia coli engineered for fuel production. Microbiology, 152(9), 2529–2536. 10.1099/mic.0.29028-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katre, G. , Ajmera, N. , Zinjarde, S. , & Ravikumar, A. (2017). Mutants of Yarrowia lipolytica NCIM 3589 grown on waste cooking oil as a biofactory for biodiesel production. Microbial Cell Factories, 16, 176 10.1186/s12934-017-0790-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N. , Maezato, Y. , Mcclure, R. S. , Brislawn, C. J. , Mobberley, J. M. , Isern, N. , … Bernstein, H. C. (2018). Phenotypic responses to interspecies competition and commensalism in a naturally‐derived microbial co‐culture. Scientific Reports, 8, 297 10.1038/s41598-017-18630-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. K. , Chou, H. , Ham, T. S. , Lee, T. S. , & Keasling, J. D. (2008). Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for biofuels production: From bugs to synthetic biology to fuels. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 19(6), 556–563. 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linck, A. , Vu, X. K. , Essl, C. , Hiesl, C. , Boles, E. , & Oreb, M. (2014). On the role of GAPDH isoenzymes during pentose fermentation in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae . FEMS Yeast Research, 14(3), 389–398. 10.1111/1567-1364.12137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, M. , Gomes, A. S. , Silva, C. M. , & Belo, I. (2018). Microbial lipids and added value metabolites production by Yarrowia lipolytica from pork lard. Journal of Biotechnology, 265, 76–85. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madzak, C. , Tréton, B. , & Blanchin‐Roland, S. (2000). Strong hybrid promoters and integrative expression/secretion vectors for quasi‐constitutive expression of heterologous proteins in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica . Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2(2), 207–216. 10.1038/sj.jim.2900821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X. , Liu, Z. , Sun, J. , & Lee, S. Y. (2017). Metabolic engineering for the microbial production of marine bioactive compounds. Biotechnology Advances, 35(8), 1004–1021. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marienhagen, J. , & Bott, M. (2013). Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the synthesis of plant natural products. Journal of Biotechnology, 163(2), 166–178. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, T. , Ito, M. , Fukuda, H. , & Kondo, A. (2004). Enantioselective transesterification using lipase‐displaying yeast whole‐cell biocatalyst. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 64(4), 481–485. 10.1007/s00253-003-1486-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y. , Wang, G. , Yang, N. , Zhou, Z. , Li, Y. , Liang, X. , … Li, J. (2011). Two‐step synthesis of fatty acid ethyl ester from soybean oil catalyzed by Yarrowia lipolytica lipase. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 4, 6 10.1186/1754-6834-4-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minty, J. J. , Singer, M. E. , Scholz, S. A. , Bae, C. H. , Ahn, J. H. , Foster, C. E. , … Lin, X. N. (2013). Design and characterization of synthetic fungal‐bacterial consortia for direct production of isobutanol from cellulosic biomass. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(36), 14592–14597. 10.1073/pnas.1218447110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlíčková, K. , Roux, E. , Athenstaedt, K. , d'Andrea, S. , Daum, G. , Chardot, T. , & Nicaud, J. M. (2004). Lipid accumulation, lipid body formation, and acyl coenzyme A oxidases of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica . Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 70(7), 3918–3924. 10.1128/AEM.70.7.3918-3924.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer, R. K. , & Johnston, J. R. (1986). Genealogy of principal strains of the yeast genetic stock center. Genetics, 113(1), 35–43. 10.1016/0735-0651(86)90006-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafpour, G. , Younesi, H. , & Ismail, K. S. K. (2004). Ethanol fermentation in an immobilized cell reactor using Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Bioresource Technology, 92(3), 251–260. 10.1016/j.biortech.2003.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T. K. , Yu, A. Q. , Ling, H. , Pratomo, J. N. K. , Choi, W. J. , Leong, S. S. J. , & Chang, M. W. (2020). Engineering Yarrowia lipolytica towards food waste bioremediation: Production of fatty acid ethyl esters from vegetable cooking oil. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 129(1), 31–40. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2019.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. , & Shi, S. (2020). Methods and products for production of wax esters. U.S. Patent No. 10,533,198.

- Ryu, S. , Hipp, J. , & Trinh, C. T. (2015). Activating and elucidating metabolism of complex sugars in Yarrowia lipolytica . Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 82(8), 1334–1345. 10.1128/aem.00457-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana, H. S. , Tortola, D. S. , Reis, É. M. , Silva, J. L. , & Taranto, O. P. (2016). Transesterification reaction of sunflower oil and ethanol for biodiesel synthesis in microchannel reactor: Experimental and simulation studies. Chemical Engineering Journal, 302, 752–762. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.05.122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, C. M. , Hussain, M. S. , Blenner, M. , & Wheeldon, I. (2016). Synthetic RNA polymerase III promoters facilitate high efficiency CRISPR‐Cas9 mediated genome editing in Yarrowia lipolytica . ACS Synthetic Biology, 5(4), 356–359. 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S. , Valle‐Rodríguez, J. O. , Khoomrung, S. , Siewers, V. , & Nielsen, J. (2012). Functional expression and characterization of five wax ester synthases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their utility for biodiesel production. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 5, 7 10.1186/1754-6834-5-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S. , Valle‐Rodríguez, J. O. , Siewers, V. , & Nielsen, J. (2014). Engineering of chromosomal wax ester synthase integrated Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants for improved biosynthesis of fatty acid ethyl esters. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 111(9), 1740–1747. 10.1002/bit.25234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. , Bajar, S. , & Bishnoi, N. R. (2014). Enzymatic hydrolysis of microwave alkali pretreated rice husk for ethanol production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Scheffersomyces stipitis and their co‐culture. Fuel, 116, 699–702. 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.08.072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steen, E. J. , Kang, Y. , Bokinsky, G. , Hu, Z. , Schirmer, A. , McClure, A. , … Keasling, J. D. (2010). Microbial production of fatty‐acid‐derived fuels and chemicals from plant biomass. Nature, 463(7280), 559–562. 10.1038/nature08721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppalakpanya, K. , Ratanawilai, S. B. , & Tongurai, C. (2010). Production of ethyl ester from esterified crude palm oil by microwave with dry washing by bleaching earth. Applied Energy, 87(7), 2356–2359. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2009.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tai, M. , & Stephanopoulos, G. (2013). Engineering the push and pull of lipid biosynthesis in oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for biofuel production. Metabolic Engineering, 15, 1–9. 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo, W. S. , Ling, H. , Yu, A. Q. , & Chang, M. W. (2015). Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of fatty acid short‐ and branched‐chain alkyl esters biodiesel. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 2015(8), 177 10.1186/s13068-015-0361-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R. A. , & Trinh, C. T. (2015). Enhancing fatty acid ethyl ester production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through metabolic engineering and medium optimization. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 111(11), 2200–2208. 10.1002/bit.25292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle‐Rodríguez, J. O. , Shi, S. , Siewers, V. , & Nielsen, J. (2014). Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of fatty acid ethyl esters, an advanced biofuel, by eliminating non‐essential fatty acid utilization pathways. Applied Energy, 115, 226–232. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. H. , Hung, W. , & Tsai, S. H. (2011). High efficiency transformation by electroporation of Yarrowia lipolytica . Journal of Microbiology, 49(3), 469–472. 10.1007/s12275-011-0433-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicki, M. , Niraula, N. , Yarrabothula, A. , Layton, D. S. , & Trinh, C. T. (2016). Engineering an Escherichia coli platform to synthesize designer biodiesels. Journal of Biotechnology, 224, 27–34. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P. , Qiao, K. , Ahn, W. S. , & Stephanopoulos, G. (2016). Engineering Yarrowia lipolytica as a platform for synthesis of drop‐in transportation fuels and oleochemicals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(39), 10848–10853. 10.1073/pnas.1607295113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J. , Han, B. , Gui, X. , Wang, G. , Xu, L. , Yan, Y. , … Jiao, L. (2018). Engineering Yarrowia lipolytica to simultaneously produce lipase and single cell protein from agro‐industrial wastes for feed. Scientific Reports, 8, 758 10.1038/s41598-018-19238-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A. Q. , Pratomo Juwono, N. K. , Leong, S. S. J. , & Chang, M. W. (2014). Production of fatty acid‐derived valuable chemicals in synthetic microbes. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2, 78 10.3389/fbioe.2014.00078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A. Q. , Pratomo, N. , Ng, T. K. , Ling, H. , Cho, H.‐S. , Leong, S. S. J. , & Chang, M. W. (2016). Genetic engineering of an unconventional yeast for renewable biofuel and biochemical production. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 115, e54371 10.3791/54371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A. , Zhao, Y. , Pang, Y. , Hu, Z. , Zhang, C. , Xiao, D. , … Leong, S. S. J. (2018). An oleaginous yeast platform for renewable 1‐butanol synthesis based on a heterologous CoA‐dependent pathway and an endogenous pathway. Microbial Cell Factories, 17, 166 10.1186/s12934-018-1014-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K. O. , Jung, J. , Kim, S. W. , Park, C. H. , & Han, S. O. (2012). Synthesis of FAEEs from glycerol in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae using endogenously produced ethanol by heterologous expression of an unspecific bacterial acyltransferase. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 109(1), 110–115. 10.1002/bit.23311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K. , Qiao, K. , Edgar, S. , & Stephanopoulos, G. (2015). Distributing a metabolic pathway among a microbial consortium enhances production of natural products. Nature Biotechnology, 33(4), 377–383. 10.1038/nbt.3095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q. , & Jackson, E. N. (2015). Metabolic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for industrial applications. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 36, 65–72. 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the appendices.