The April 7, 2020, Wisconsin election produced a large natural experiment to help understand the transmission risks of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). As of April 14, 2020, 1 551 711 total votes were cast (https://bit.ly/2yWPhlF),1 and 1 138 491 absentee ballots were returned as of April 21, 2020,1 suggesting that approximately 413 220 people voted in person. Waiting times in Milwaukee averaged 1.5 to 2 hours.2 Poll workers had surgical masks and latex gloves, hand sanitizer was made available to voters, isopropyl alcohol wipes were used to clean voting equipment, and painting tape and signs were used to facilitate social distancing.1

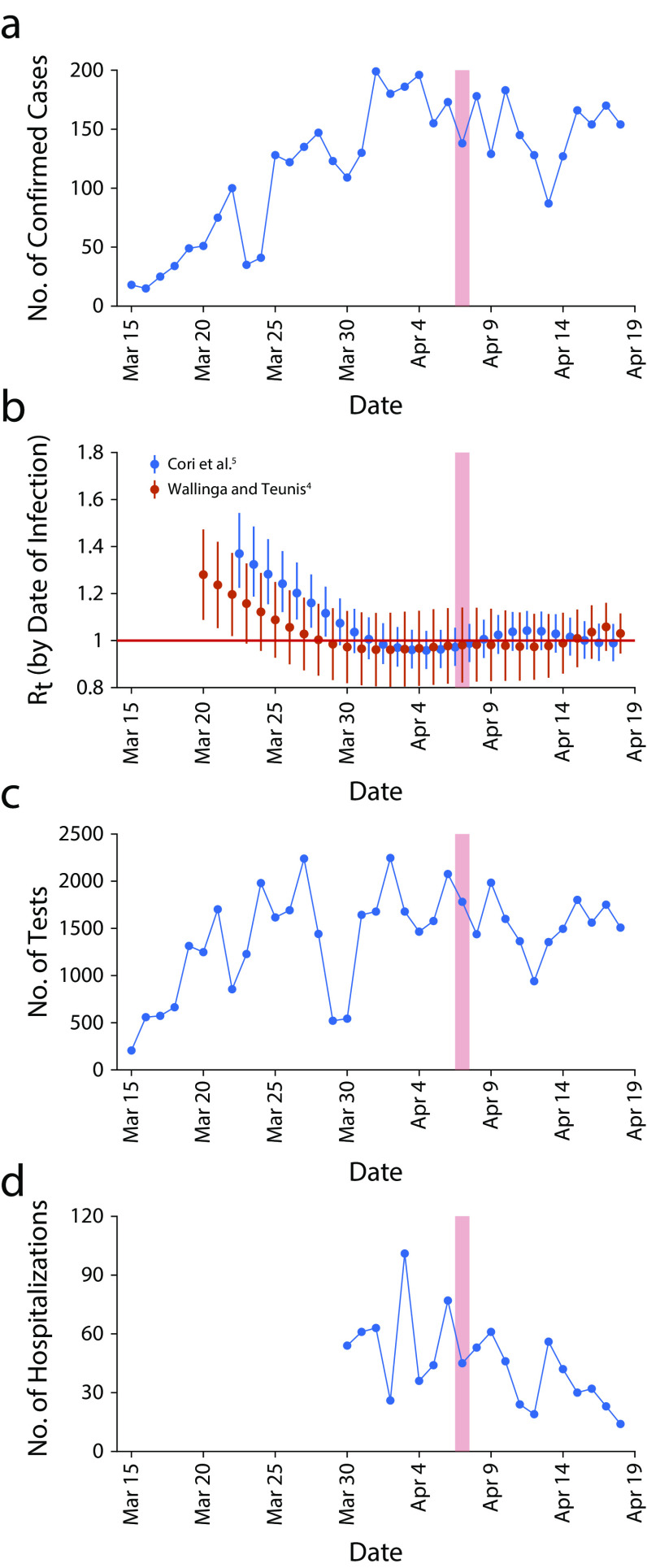

Wisconsin tracks cases confirmed by testing (Figure 1a) and throughout April 2020 have restricted testing to frontline workers and those hospitalized with serious illness.3 We used a deconvolution-based method to reconstruct the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic curve by dates of infections rather than dates of reporting by health authorities and then used two different methods4,5 to estimate the instantaneous reproduction number R_t , which is the average number of secondary cases generated by one primary case with the time of infection on day t

, which is the average number of secondary cases generated by one primary case with the time of infection on day t , from March 25 (the start of the safer-at-home order) through April 18 (Appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

, from March 25 (the start of the safer-at-home order) through April 18 (Appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

SARS-CoV-2 Dynamics Surrounding the April 7, 2020 Election in Wisconsin: (a) Number of Daily Confirmed SARS-CoV2 Cases in Wisconsin, March 15–April 19; (b) Estimated Instantaneous Reproduction Number Rt (and 95% Confidence Intervals) Each Day, March 25 (the Start of the Safer-at-Home-Order in Wisconsin) to April 18 Using 2 Different Methods; (c) Number of SARS-CoV-2 Tests Performed Each Day, March 15–April 18; (d) Number of New SARS-CoV-2 Hospitalizations in Wisconsin Each Day, March 30–April 18

Note. The thick bar in each panel depicts April 7, 2020, the date of the Wisconsin election. In generating the curve in panel C, a possible misentry in the original data set3 led to the cumulative test count on March 29 being smaller than the day before; in response, we replaced the March 29 cumulative case count by the average value between March 28 and 30.

As seen in Figure 1b, there is no detectable spike in R_t on April 7. The number of SARS-CoV-2 tests performed in Wisconsin (https://bit.ly/2L13YXj) has been relatively stable throughout April (Figure 1c), suggesting that reduced testing capacity in the days after April 7, which could have censored some of the April 7 infections, did not occur. Moreover, new SARS-CoV-2 hospitalizations in Wisconsin have steadily declined throughout April (Figure 1d), from a high of 101 on April 3 to a low of 14 on April 18 (https://bit.ly/2L13YXj), suggesting that daily new hospitalizations are much less than testing capacity.

on April 7. The number of SARS-CoV-2 tests performed in Wisconsin (https://bit.ly/2L13YXj) has been relatively stable throughout April (Figure 1c), suggesting that reduced testing capacity in the days after April 7, which could have censored some of the April 7 infections, did not occur. Moreover, new SARS-CoV-2 hospitalizations in Wisconsin have steadily declined throughout April (Figure 1d), from a high of 101 on April 3 to a low of 14 on April 18 (https://bit.ly/2L13YXj), suggesting that daily new hospitalizations are much less than testing capacity.

The lengths of the incubation period and the reporting delay imply that April 7 infections would not be reported until April 17 on average, with most cases being reported between April 11 and 22. Taken together, there is no evidence to date that there was a surge of infections attributable to the April 7, 2020 election in Wisconsin, which has a low level of SARS-CoV-2 transmission relative to the United States.

Finally, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services announced on May 15 that 71 people who either voted in person or worked at the polls on April 7 have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.6 However, many of these people also experienced nonvoting exposures,6 and hence this fact is not necessarily inconsistent with our population-level analysis. To put this information into perspective, if we assume that the SARS-CoV-2 fatality rate among symptomatic patients who were physically capable of voting in person on April 7 (e.g., not including nursing home residents) is 1% (using the fatality rate of known cases for people younger than 60 years7), then (in the worst case, in which all 71 cases were attributable to voting) we would expect 0.71 deaths out of 413 220 people, which is the fatality risk of driving an automobile approximately 140 miles (https://bit.ly/35mRMJq). However, in addition to the individual risk of voting on April 7, there is the community risk: how many downstream cases will these 71 original cases generate? According to Figure 1b, the reproduction number in Wisconsin has been hovering near the value of one for all of April. If this value was much larger than one (as it was in, say, January) then these 71 cases would cause a lot of downstream damage, and if this value was clearly smaller than one then they would cause minimal damage. But a value near one, coupled with the small number of cases, means that it is very difficult to reliably predict the amount of downstream damage.

Taken together, it appears that voting in Wisconsin on April 7 was a low-risk activity.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1. Wisconsin Election Commission. Available at: https://elections.wi.gov. Accessed May 16, 2020.

- 2.Spicuzza M. “A very sad situation for voters”: Milwaukeeans brave wait times as long as 2 1/2 hours, top election official says. 2020. Available at: https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/politics/elections/2020/04/07/wisconsin-election-milwaukee-voters-brave-long-wait-lines-polls/2962228001. Accessed May 16, 2020.

- 3.Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report. 2020. Available at: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p02624-2020-03-13.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2020.

- 4.Wallinga J, Teunis P. Different epidemic curves for severe acute respiratory syndrome reveal similar impacts of control measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):509–516. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cori A, Ferguson NM, Fraser C, Cauchemez S. A new framework and software to estimate time-varying reproduction numbers during epidemics. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(9):1505–1512. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wahlberg D. 71 people who went to the polls on April 7 got COVID-19; tie to election uncertain. 2020. Available at: https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/health-med-fit/71-people-who-went-to-the-polls-on-april-7-got-covid-19-tie-to/article_ef5ab183-8e29-579a-a52b-1de069c320c7.html. Accessed May 16, 2020.

- 7. Verity R, Okell LC, Dorigatti I, et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020; Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]