Abstract

Objectives. To measure changes in the contraceptive methods used by Title X clients after implementation of Delaware Contraceptive Access Now, a public–private initiative that aims to increase access to contraceptives, particularly long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs).

Methods. Using administrative data from the 2008–2017 Family Planning Annual Reports and a difference-in-differences design, we compared changes in contraceptive method use among adult female Title X family planning clients in Delaware with changes in a set of comparison states. We considered permanent methods, LARCs, moderately effective methods, less effective methods, and no method use.

Results. Results suggest a 3.2-percentage-point increase in LARC use relative to changes in other states (a 40% increase from baseline). We were unable to make definitive conclusions about other contraceptive method types.

Conclusions. Delaware Contraceptive Access Now increased LARC use among Title X clients. Our results have implications for states considering comprehensive family planning initiatives.

Delaware Contraceptive Access Now (DelCAN) is a statewide initiative that aims to increase access to the full range of contraceptives for women in Delaware, and particularly to long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs).1 The initiative was motivated by high rates of unintended pregnancy in Delaware. In 2014, 1 year before the program went into effect, 48% of pregnancies were unwanted or occurred earlier than desired, the highest rate in the nation.2

DelCAN has been implemented in the context of widespread state policy activity aimed at improving access to contraceptives.3,4 Many of these efforts have focused on LARCs, the most effective reversible contraceptive methods.5 This policy focus has followed from strengthened recommendations by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics on the use of LARCs among all women at risk for unintended pregnancy.6,7 Despite these recommendations, a number of barriers prevent access and uptake of LARCs, which has historically been low in the United States.8 Supply-side challenges include a lack of clinical expertise in LARC insertion and removal and the unique operational challenges of providing LARCs given the need for providers to stock, store, and be reimbursed for LARC devices.9–11 Many states have started to respond by altering public payment policies and by assisting providers in obtaining training.3,12,13 LARCs are also less familiar to patients, can require multiple trips to a provider, and are expensive if not covered by insurance.14–16

While most states are now engaged in efforts to expand access to contraceptive services, other states have scaled back services. For example, Texas dramatically reduced its support of family planning clinics in 2011.17

There has been a handful of state and local initiatives that share DelCAN’s comprehensive approach. The Colorado Family Planning Initiative provided free services through its Title X system, trained providers, and expanded Title X capacity.18 The program had important public health impacts.18–20 For example, quasi-experimental evidence suggests that the program reduced adolescent birth rates by 6.5%.19 The Contraceptive CHOICE project provided free contraceptive counseling and services to more than 9000 women in the St Louis, Missouri, area who expressed an interest in LARCs and were either not using contraception or had a desire to change methods. Seventy-five percent of clients chose a LARC method, suggesting that many women with an unmet demand for LARCs will choose the method when costs are not a barrier.21 However, results from CHOICE are not generalizable given that many women may not prefer LARCs to other methods.

In this study, we examined the association of DelCAN with changes in contraceptive method use among adult Title X family planning clients. Delaware’s Title X system is composed of 52 sites. Like most states, client volumes have declined over time, from 22 000 female clients in 2008 to 16 000 in 2017. The state is the sole grantee, and the number of sites has remained stable over time. Approximately 68% of clients are at 100% or below of Department of Health and Human Services federal poverty guidelines (FPG) and have access to free contraceptive services per Title X rules.

DELAWARE CONTRACEPTIVE ACCESS NOW PROGRAM FEATURES

The goal of DelCAN is to ensure that all women in Delaware have same-day access to the full range of contraceptive methods, regardless of insurance or ability to pay. While many DelCAN activities are focused on addressing the unique challenges of providing LARCs, the program’s intended goal of improving access to all methods underscores the central role of patient preferences and autonomy in family planning.22 A comprehensive description of the program is provided elsewhere, but here we summarize program components that had a direct impact on Title X.1

DelCAN is a partnership between the state of Delaware and Upstream USA.23 From May 2015 to late June 2016, funding from the Delaware Division of Public Health was repurposed to purchase LARC devices. Resources were also used to help clinics provide free methods to clients of all income levels. Before DelCAN, clients at 100% FPG or below received free care and clients above 100% FPG paid a sliding-scale coinsurance fee.

Effective January 2017, Medicaid provided a mechanism for federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) to obtain compensation for LARCs that were not included in the FQHC prospective visit rates from Medicaid. This allowed FQHCs to maintain adequate stock of LARCs and replaced the need for the state to directly purchase devices. While not all Title X agencies in Delaware are FQHCs, the vast majority of FQHCs receive Title X funds. Title X clinics that did not have an FQHC designation continued to rely on Delaware Division of Public Health financing for LARC devices.

Starting in February 2016, Upstream USA provided training for clinicians and support staff (e.g., medical assistants, front desk staff, accounting and billing, and other administrative staff) to increase clinical, counseling, and administrative capacity for providing the full range of contraceptive methods. Most clinics had received training by November 2016 and began participating in ongoing technical assistance. With the exception of a collection of school-based health centers, nearly all Title X clinics received training.

A public awareness campaign called “Be Your Own Baby” was launched in late May 2017 and ended in October 2018. The campaign included social media, online music videos, and paid advertising that targeted women aged 18 to 29 years in Delaware. The call to action was to visit the Be Your Own Baby Web page (https://beyourownbaby.org), which steered visitors to a nearby participating clinic that could provide free same-day contraceptive services.

DelCAN may have changed contraceptive method use of Title X clients by improving clinic capacity to provide the full range of contraceptives and by reducing the out-of-pocket price that clients above 100% of FPG faced. The program may have also led to changes in the contraceptives provided via Title X by changing the composition of who showed up for care.

METHODS

Aggregate data came from the 2008–2017 Family Planning Annual Reports (FPARs).24 These administrative data cover the entire United States and describe Title X clients. We make particular use of a state-level table in the FPAR that describes the primary contraceptive methods used by female family planning clients. A family planning client is a client who obtains services at a Title X clinic for the purpose of becoming pregnant or avoiding pregnancy.24 Primary contraceptive method use refers to the most effective method adopted or continued at a client’s last family planning encounter of the year. We obtained a restricted-use version of the FPAR that provided a longer time series than is available in the public-use reports and had additional detail on contraceptive methods by age group.

We grouped primary methods into the effectiveness categories used by the Office of Population Affairs: permanent methods (female or male sterilization), LARCs (intrauterine devices or contraceptive implants), moderately effective methods (injectable contraceptives, vaginal rings, birth control patches, birth control pills, diaphragms, or cervical caps), and less effective methods (male or female condoms, birth control sponges, withdrawal, fertility-based awareness, lactational amenorrhea, or spermicides).24 Our outcomes of interest were the percentage using each of these method categories or no method, and we focused on the population at risk for unintended pregnancy. This population excludes women who were pregnant or seeking pregnancy and women who were abstinent.

Study Population

We excluded women younger than 20 years because of concerns about face validity. The FPAR suggested that 3 times as many adolescents were not using any method compared with Medicaid administrative data and state-specific survey estimates (Section 1 of the Appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We also excluded Colorado and Texas because they both had large policy changes targeted at Title X clinics during the study period.17,18 The unit of observation was age group–state–year. Age groups included those aged 20 to 24 years, 25 to 34 years, and 35 years or older. The sample size was 1470 age group–state–year cells in total or 490 per age group.

The main limitation with the FPAR is that some clients are recorded as having an unknown method. The percentage with an unknown method is particularly high in Delaware and has varied over time. In 2011, 6.6% of adult female family planning users in Delaware had an unknown method. The percentage with an unknown method increased to 50.9% in 2013 before declining to 23.9% in 2015 and remaining at approximately the same level in 2016 and 2017.

To handle unknown method cases in Delaware and the comparison states, we allocated them to one of the method categories, including no method. For each method category, we added allocated cases to observed cases to obtain an estimate of method category use. We obtained the proportion allocated to permanent, LARC, and moderate methods from a uniform-random draw between the minimum and maximum observed proportion of clients using the given method within age group and state. For less effective and no method use, the uniform-random draw was between the minimum and 2 times the maximum observed proportion for that age group and state. The “two times” factor for less effective and no method use was based on expert consultation with Delaware state officials and from additional empirical analyses described in Section 2 of the Appendix that suggested that those method categories were more likely to be coded as unknown. In sensitivity analyses, our main result for LARC changed little when we varied this adjustment factor between 1 and 3 as compared with using a value of 2. To account for the uncertainty attributable to imputation, we repeated the allocation 40 times and combined the estimates during analysis using the standard multiple imputation combining algorithm.25

We merged data from the FPAR with a series of state-by-year policy and sociodemographic characteristics. We obtained Medicaid income thresholds for parents, childless adults, pregnant women, and family planning waiver eligibility.26,27 We categorized each state’s time-varying abortion environment as supportive (1 or no restrictions), middle ground (2 or 3 restrictions), restrictive (4 or 5 restrictions), or extremely restrictive (6 or more restrictions).28 We obtained state-by-year sociodemographics from the American Community Survey that described the characteristics of women aged 20 to 44 years that were below 250% of the federal poverty level—the primary population served by Title X.24 These characteristics included average age, percentage married, average number of children per household, percentage non-Hispanic White, percentage non-Hispanic Black, percentage Hispanic, percentage insured, percentage noncitizen, percentage with a high-school education or less, percentage working, and percentage below the federal poverty level. To account for differences in the geographic accessibility of community services and the frequency of travel between states, we also obtained average commute times for workers and the percentage of workers who work in a different state than they reside.

Statistical Analysis

We assessed the association of DelCAN with contraceptive method use using a difference-in-differences approach that compared changes in the contraceptive method types used in Delaware from the preimplementation (2008–2014) with the postimplementation (2015–2017) period to changes in all other states, save Texas and Colorado, during the same periods. The primary assumption of our approach is that changes in other states reflect the changes that would have occurred in Delaware had the intervention never been implemented. Importantly, our approach assumed that, in the absence of DelCAN, Delaware would have engaged in the same level of contraceptive access reforms as other states during the same period. Although that assumption is untestable, we investigated its plausibility by graphically inspecting trends in Delaware and the comparison states leading up to the implementation year (2015) and by formal statistical tests for differences in linear pretreatment trends.

We implemented the difference-in-differences using a linear regression that controlled for state fixed effects to account for any stable state differences, year fixed effects to account for national trends common across states, and state-specific linear trends to adjust for preexisting trend differences. We also controlled for the policy and the sociodemographic variables described previously. The Medicaid income thresholds accounted for Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion and Delaware’s historically generous Medicaid program. The abortion variables controlled for changes in abortion restrictions that may have led to different contraception decisions.28 We estimated models for all ages and by age group.

We weighted all regression models by the number of adult female family planning clients by age group, state, and year. However, we came to similar conclusions when we used unweighted models. Standard errors accounted for the uncertainty of imputation and for state clustering. Typical approaches for clustering of standard errors are known to be biased when a single state was treated. To account for that, were estimated P values by using a bootstrap procedure that accounts for a single treated cluster.29 We conducted a number of sensitivity analyses that we describe in the Appendix and summarize in the Results section. Section 3 of the Appendix reports on specific method results not described here.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes preimplementation-period (2008–2014) characteristics in Delaware and the comparison states. For example, Delaware women were significantly more likely to be insured, less likely to be married, and less likely to be noncitizens. Delaware Title X users were significantly more likely to have public coverage and less likely to be insured, compared with Title X users in the comparison states. Differences in preimplementation-period characteristics between Delaware and the comparison group underscore the importance of controlling for state fixed effects, which account for all observed and unobserved differences that are stable over time.

TABLE 1—

Preimplementation Period Characteristics of Adult Female Family Planning Clients: Delaware and the Comparison States, 2008–2014

| DE (n = 14 295a), Mean ±SE or % (SE) | Comparison States (n = 3 283 128a), Mean ±SE or % (SE) | P | |

| General population characteristics of adult reproductive age women, < 250% of FPL (ACS) | |||

| Age, y | 30.9 ±0.09 | 31.0 ±0.01 | .32 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 48.6 (0.54) | 47.6 (1.43) | .49 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 30.6 (0.48) | 17.1 (0.69) | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 15.3 (0.49) | 26.4 (1.73) | < .001 |

| Number of children | 1.4 ±0.02 | 1.4 ±0.01 | < .001 |

| Insured | 80.6 (0.60) | 68.0 (0.45) | < .001 |

| ≤ high school education | 55.5 (0.77) | 54.8 (0.23) | .37 |

| < 100% FPL | 37.4 (0.69) | 39.6 (0.14) | .003 |

| Working | 60.4 (0.60) | 56.2 (0.28) | < .001 |

| Work in different state, % of workers | 9.6 (0.54) | 2.2 (0.13) | < .001 |

| Commute time to work, minutes | 21.8 ±0.22 | 23.0 ±0.16 | < .001 |

| Married | 28.1 (0.43) | 34.0 (0.24) | < .001 |

| Noncitizen | 12.0 (0.31) | 17.5 (0.92) | < .001 |

| Characteristics of Title X family planning users (FPAR) | |||

| Age profile, y | |||

| 20–24 | 37.9 (1.51) | 38.4 (0.28) | .71 |

| 25–34 | 41.5 (0.75) | 42.2 (0.23) | .37 |

| ≥ 35 | 20.7 (0.80) | 19.4 (0.23) | .13 |

| Health insurance coverage profile | |||

| Public coverage | 32.7 (2.51) | 24.8 (1.12) | .004 |

| Private coverage | 16.3 (0.87) | 10.1 (0.83) | < .001 |

| Uninsured | 51.0 (2.49) | 65.1 (1.82) | < .001 |

| < 101% FPG | 67.2 (1.41) | 71.6 (0.80) | .007 |

Note. ACS = American Community Survey; FPG = federal poverty guidelines; FPL = federal poverty level (according to the US Census Bureau). All estimates are weighted. The unweighted sample size is n = 1029 age group by state by year cells. The comparison states were the District of Columbia and all states except Colorado and Texas.

Source. Restricted use versions of the 2008–2014 Title X Family Planning Annual Report (FPAR); 2008–2014 American Community Survey.

Average annual count of adult female family planning clients.

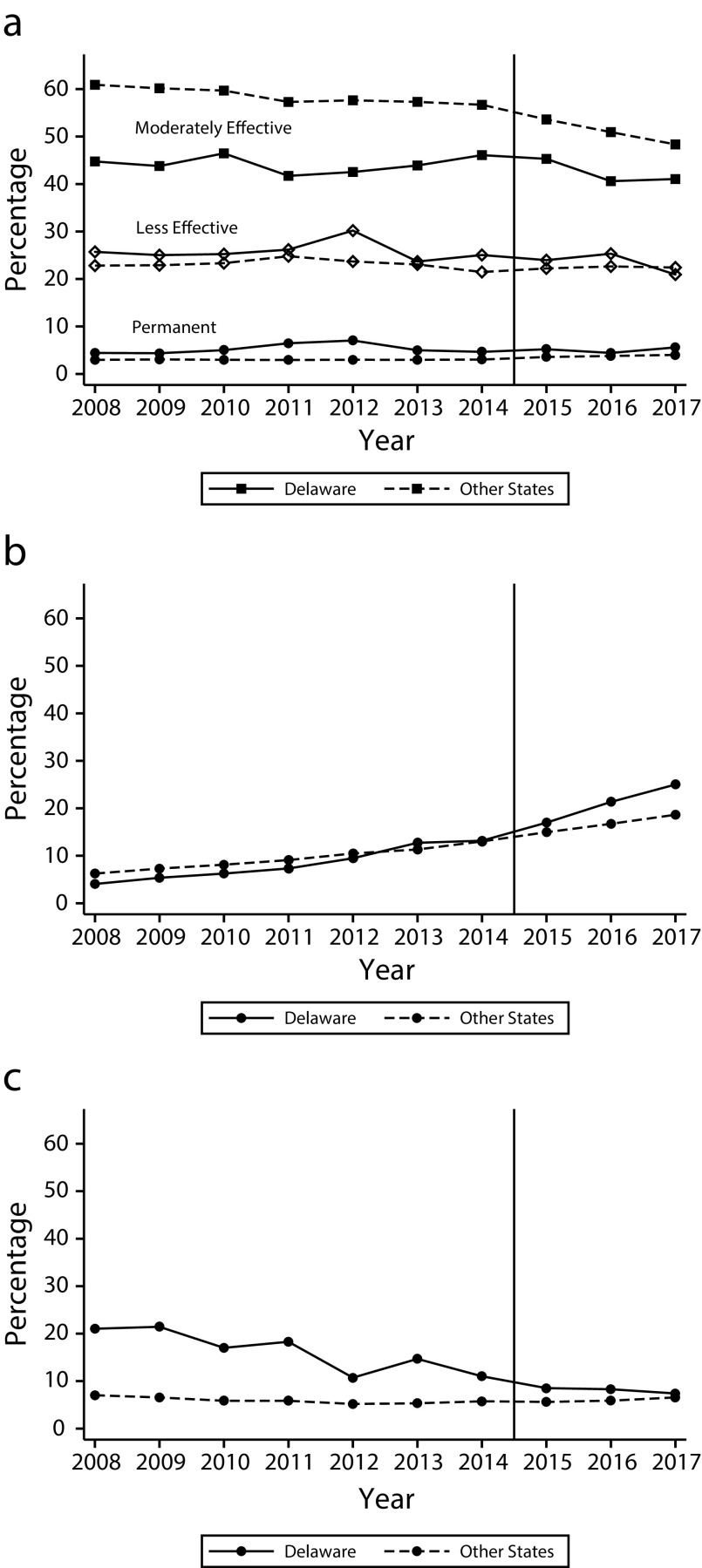

Figure 1 describes trends in contraceptive method types in Delaware and the comparison states. Permanent method use was higher in Delaware than in other states during the preimplementation period (e.g., in 2012 the rate was 7% in Delaware and 3% in the comparison states), but was approximately equal in the postimplementation period. Moderately effective method use fluctuated throughout the period in Delaware, but had no consistent trend in the pre- or postimplementation periods. Comparatively, there was a slight decline in moderately effective methods in the comparison states. Less effective method use declined in both Delaware and the comparison states during the study period. The use of LARCs increased from 4.1% in 2008 to 13.2% in 2014 in Delaware and from 6.3% in 2008 to 13.0% in 2014 in the comparison states. After the implementation of the intervention, LARC use in Delaware increased more rapidly compared with the comparison states, reaching 25.0% in 2017 versus 18.6% in other states. No method use declined throughout the study period in Delaware while remaining relatively flat in the comparison states.

FIGURE 1—

Primary Contraceptive Method Category Among Adult Family Planning Clients at Risk for Unintended Pregnancy by (a) Permanent, Moderate, and Less Effective Methods; (b) Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives; and (c) No Method Use: Delaware and Comparison States, 2008–2017

Note. Estimates are weighted by the number of female family planning clients by age group, state, and year. Unknown method types are allocated to a known type. The sample size was n = 1470 age group by state by year cells. The comparison states were the District of Columbia and all states except Colorado and Texas.

Source. 2008–2017 Title X Family Planning Annual Reports.

We failed to reject equal linear pretrends for permanent, moderate, and less effective method use, but rejected equal linear pretrends for LARC and no method use (Section 4 in the Appendix). These results highlight the importance of controlling for state-specific trends and conducting the robustness tests we describe later in this section.

Table 2 describes the main results from the difference-in-differences model for all adult female family planning clients at risk for unintended pregnancy. Permanent method use declined by 1.7 percentage points, relative to the change in the comparison states and holding all other variables in the model constant, but the estimate had a relatively large degree of statistical uncertainty (P = .09). LARC use increased by 3.2 percentage points (P = .012) relative to the change in the comparison states. This represents a 40% increase from the Delaware baseline. There were no statistically significant changes to moderate, less effective, or no methods.

TABLE 2—

Difference-in-Differences Estimates of the Association of DelCAN With the Primary Contraceptive Method Type Among Adult Family Planning Clients at Risk for Unintended Pregnancy: Delaware, 2008 to 2017

| % Using Method in Delaware During the Preimplementation Period | DD Estimates (SE) | P | |

| Contraceptive method categories | |||

| Permanent methods | 5.3 | −1.7 (0.90) | .1 |

| LARCs | 8.0 | 3.2 (1.58) | .012 |

| Moderate methods | 44.1 | 1.9 (3.35) | .34 |

| Less effective methods | 25.9 | −1.2 (2.99) | .46 |

| No methods | 16.7 | −2.2 (3.10) | .22 |

Note. DD = difference-in-differences; DelCAN = Delaware Contraceptive Access Now; LARCs = long-acting reversible contraceptives. Each estimate comes from a separate regression. All estimates are weighted by the number of female family planning clients by age group, state, and year. Covariates are described in the text. SEs account for imputation variance and state clustering. P values were obtained from a bootstrap that accounted for state clustering and a single treated cluster. The unweighted sample size was 1470 age group by state by year cells. On average, there were 13 265 adult female clients per year in Delaware and 3.1 million per year in the comparison states from 2008 to 2017. The comparison states were the District of Columbia and all states except Colorado and Texas.

Source. Restricted use versions of the 2008–2017 Title X Family Planning Annual Report; 2008–2017 American Community Survey; Kaiser Family Foundation26; and the Guttmacher Institute.

Table 3 describes results by age group. While the percentage point change for permanent methods was larger for older age groups, the relative change was the largest for younger women aged 20 to 24 years (a 75% reduction from the baseline rate of 0.4%). The percentage-point change in LARC use was generally consistent across age groups, but was largest on a relative basis for women aged 20 to 24 years. “No method” decreased significantly among women aged 35 years and older.

TABLE 3—

Age Group–Specific Difference-in-Differences Estimates of the Association of DelCAN With the Primary Contraceptive Method Type Used by Adult Family Planning Clients at Risk for Unintended Pregnancy: Delaware, 2008 to 2017

| % Using Method in Delaware During the Preimplementation Period | DD Estimate (SE) | P | |

| Age 20–24 y | |||

| Permanent methods | 0.4 | −0.3 (0.15) | .019 |

| LARCs | 5.9 | 3.2 (2.26) | .023 |

| Moderate methods | 48.9 | 3.3 (4.15) | .23 |

| Less effective methods | 26 | −3.7 (4.09) | .16 |

| No methods | 18.9 | −2.5 (4.39) | .18 |

| Age 25–34 y | |||

| Permanent methods | 3.8 | −1.3 (0.71) | .052 |

| LARCs | 10.2 | 3.3 (2.74) | < .001 |

| Moderate methods | 46.7 | 1.4 (4.15) | .46 |

| Less effective methods | 25.1 | −2.8 (3.95) | .1 |

| No methods | 14.1 | −0.6 (3.81) | .59 |

| Age ≥ 35 y | |||

| Permanent methods | 17.2 | −3.4 (2.68) | .045 |

| LARCs | 7.4 | 2.9 (2.50) | .016 |

| Moderate methods | 30.2 | 1.0 (4.18) | .62 |

| Less effective methods | 27.4 | 4.8 (3.95) | .06 |

| No methods | 17.8 | −5.3 (3.92) | .009 |

Note. DD = difference-in-differences; DelCAN = Delaware Contraceptive Access Now; LARCs = long-acting reversible contraceptives. Each estimate comes from a separate regression. All estimates are weighted by the number of female family planning clients by age group, state, and year. SE accounts for imputation variance and state clustering. P values were obtained from a bootstrap that accounted for state clustering and a single treated cluster. The unweighted sample size was 490 per age group. In Delaware there were an average of 4752 clients aged 20–24 years, 5629 aged 25–34 years, and 2886 aged ≥ 35 years seen per year. In the comparison states there were 1.1 million, 1.3 million, and 0.6 million, respectively. The comparison states were the District of Columbia and all states except Colorado and Texas.

Source. Restricted use versions of the 2008–2017 Title X Family Planning Annual Report; 2008–2017 American Community Survey; Kaiser Family Foundation; and the Guttmacher Institute.

In the Appendix, we present several sensitivity analyses. We came to similar conclusions when we controlled for different sociodemographic and policy covariates, using alternative control states and including versus excluding the state-specific trends. We examined the use of specific methods and found that changes in LARC use were greater for contraceptive implants than for intrauterine devices. We also examined if we came to similar conclusions using the synthetic control method, an alternative study design to that of the difference-in-differences.30 The synthetic control method estimates exhibited lower statistical power than the difference-in-differences estimates, but the direction and magnitudes of synthetic control method estimates for both no method use and LARC use were similar to the difference-in-differences estimates. The synthetic control method, however, suggested different conclusions about permanent method use. The point estimate was close to zero (–0.20) and not statistically significant (P = .92).

We also examined how sensitive our results were to alternative assumptions about unknown cases. When we excluded all unknown method categories from the denominator, which effectively assumes that the distribution of method categories was the same for known and unknown users, we estimated a 6.5-percentage-point increase in LARC use. We also examined models that varied our assumption about how much more likely less effective and no method users were to be counted as unknown. Assuming that they were as likely to be counted as unknown compared with other method users resulted in a difference-in-difference estimate of LARC use of 2.7 percentage points. Assuming they were 3 times as likely resulted in an estimate of 3.5 percentage points.

DISCUSSION

Our estimates suggest that DelCAN was associated with a 3.2% increase in LARC use, a 40% relative change from baseline. Sensitivity analyses of our approach to unknown method types suggested a range of estimates from 2.7 to 6.5 percentage points. Estimates for moderate, less effective, and no methods were not sufficiently precise to come to firm conclusions.

Our results provide suggestive evidence that some of the increase in LARC was obtained by women who would have otherwise obtained a permanent method. This aligns with a broader national trend that suggests that increased LARC use over the past decade has partly come from substitution away from sterilization.8,31 However, our difference-in-differences estimate had a large degree of statistical uncertainty (P = .09) and we did not come to similar results in alternative models. Additional research is needed to fully understand the association of the intervention with permanent method use. Associations with permanent method use has important implications given that substitution away from permanent methods would provide clients with a fuller opportunity to have more intended births and would moderate any effects to unintended pregnancy.

Limitations

The most important limitation we faced was high and fluctuating rates of unknown method types in Delaware. While we cannot guarantee that our estimates reflect true population change without any influence from measurement error, our approach minimizes the impact of unknown cases, and sensitivity analyses provide a range of estimates under different assumptions. Despite the limitations of the FPAR, it is the only state representative source of information on the contraceptive methods used by Title X clients. It provides critical information that would not otherwise be available.

Our difference-in-differences design and our handling of unknown method types provide a substantial improvement over a previous descriptive study of contraceptive method trends using Delaware’s FPAR data.32 This previous analysis assumed that the distribution of method types among clients with a known method type was the same as the distribution among those with an unknown type. As we show in Section 2 of the Appendix, that assumption is not supported by the data.

We were also unable to untangle the specific DelCAN components that were more or less important in altering method use patterns. The associations we observed include the contributions of additional Title X resources that supported device stocking and reductions in out-of-pocket price for those over 100% of the FPG, improved clinical and business operations expertise obtained through trainings, and changes in client composition beyond the factors we observed.

Public Health Implications

It is important to evaluate our results in relation to other family planning initiatives so that future policy can be shaped around the most effective strategies. A recent study on the ACA’s contraceptive coverage mandate that accounted for pre-ACA state mandates suggested that the ACA mandate increased injectable contraceptives, but not LARCs.33 This could suggest that the device stocking or training components of programs like DelCAN are important for increasing access to LARCs. It is also important to compare our results with other comprehensive state efforts such as the Colorado Family Planning Initiative. Unfortunately, no study of the Colorado Family Planning Initiative, to our knowledge, has used a similar quasi-experimental design to estimate effects on contraceptive method use.

Modern contraception and the Title X program have been shown to improve outcomes for both women and their children.8 However, increasing access to contraceptives generally and to the most effective reversible methods specifically is difficult in the context of systemic barriers and the imperative to balance improved access with reproductive autonomy.22 Our results suggest that programs like DelCAN are capable of increasing the use of the most effective reversible methods. This is an important implication for other states, such as Washington, Massachusetts, and North Carolina that are embarking on similar efforts.23 This study only considered the first 3 years of DelCAN implementation. Future planned work that is part of an ongoing evaluation will examine program effects over a longer period and include other outcomes such as unintended pregnancy.34

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by infrastructural support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, population research infrastructure grant P2C-HD041041, and a research grant from a private philanthropic foundation.

We thank participants at the 2019 Association for Public Policy Analysis & Management Fall Research Conference for helpful comments.

Note. No granting organization had any involvement in the analysis and interpretation of the data, nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No author has a conflict to report.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The study was approved by the University of Maryland institutional review board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Choi YS, Rendall MS, Boudreaux M, Roby DH. Summary of the Delaware Contraceptive Access Now (DelCAN) initiative. 2019. Available at: https://popcenter.umd.edu/delcaneval/summary-init. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- 2.Kost K, Maddow-Zimet I, Kochhar S. Pregnancy desires and pregnancies at the state level: estimates for 2014. Guttmacher Institute. December 2018. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/pregnancy-desires-and-pregnancies-state-level-estimates-2014. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- 3.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Increasing access to contraception. 2019. Available at: http://www.astho.org/Programs/Maternal-and-Child-Health/Increasing-Access-to-Contraception. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- 4.Sawhill IV, Guyot K. Preventing unplanned pregnancy: lessons from the states. June 24, 2019. The Brookings Institution. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/preventing-unplanned-pregnancy-lessons-from-the-states. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Contraceptive effectiveness. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/index.htm#Contraceptive-Effectiveness. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- 6.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Increasing access to contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. October 2015. Available at: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2015/10/increasing-access-to-contraceptive-implants-and-intrauterine-devices-to-reduce-unintended-pregnancy. Accessed May 4, 2020.

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics. Contraception for adolescents: policy statement. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1244–e1256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey MJ, Lindo JM. Access and use of contraception and its effects on women’s outcomes in the United States. In: Averett SL, Argys LM, Hoffman SD, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy. Vol 1. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017. pp. 219–257. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moniz M, Chang T, Heisler M, Dalton VK. Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception: the time is now. Contraception. 2017;95(4):335–338. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beeson T, Wood S, Bruen B, Goldberg DG, Mead H, Rosenbaum S. Accessibility of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) in federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) Contraception. 2014;89(2):91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strasser J, Borkowski L, Couillard M, Allina A, Wood SF. Access to removal of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods is an essential component of high-quality contraceptive care. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(3):253–255. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moniz MH, Chang T, Davis MM, Forman J, Landgraf J, Dalton VK. Medicaid administrator experiences with the implementation of immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception. Womens Health Issues. 2016;26(3):313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moniz MH, Dalton VK, Davis MM et al. Characterization of Medicaid policy for immediate postpartum contraception. Contraception. 2015;92(6):523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frost JJ, Lindberg LD, Finer LB. Young adults’ contraceptive knowledge, norms and attitudes: associations with risk of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44(2):107–116. doi: 10.1363/4410712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pace LE, Dusetzina SB, Mark Fendrick A, Keating NL, Dalton VK. The impact of out-of-pocket costs on the use of intrauterine contraception among women with employer-sponsored insurance. Med Care. 2013;51(11):959–963. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a97b5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergin A, Tristan S, Terplan M, Gilliam ML, Whitaker AK. A missed opportunity for care: two-visit IUD insertion protocols inhibit placement. Contraception. 2012;86(6):694–697. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White K, Grossman D, Hopkins K, Potter JE. Cutting family planning in Texas. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(13):1179–1181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1207920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricketts S, Klingler G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline in births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132. doi: 10.1363/46e1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindo JM, Packham A. How much can expanding access to long-acting reversible contraceptives reduce teen birth rates? Am Econ J Econ Policy. 2017;9(3):348–376. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldthwaite LM, Duca L, Johnson RK, Ostendorf D, Sheeder J. Adverse birth outcomes in Colorado: assessing the impact of a statewide initiative to prevent unintended pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e60–e66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Madden T, Peipert JF. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the contraceptive CHOICE project in review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(5):349–353. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomez AM, Fuentes L, Allina A. Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):171–175. doi: 10.1363/46e1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Upstream USA. Partnerships. Available at: https://upstream.org/partnerships. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- 24.Flower CI, Gable J, Wang J, Lasater B. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2018. Family Planning Annual Report: 2017 national summary. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. State category. Medicaid/CHIP eligibility limits. 2019. Available at: https://www.kff.org/state-category/medicaid-chip/medicaidchip-eligibility-limits. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- 27.Burns ME, Dague L, Kasper M. Medicaid waiver dataset: coverage for childless adults 1996–2014. Version 1.0. University of Wisconsin–Madison. May 20, 2016. Available at: https://www.disc.wisc.edu/archive/Medicaid/index.html. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- 28.Guttmacher Institute. An overview of abortion laws. State policies in brief. 2019. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-abortion-laws. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- 29.Ferman B, Pinto C. Inference in differences-in-differences with few treated groups and heteroskedasticity. Rev Econ Stat. 2019;101(3):452–467. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. Am J Pol Sci. 2015;59(2):495–510. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J. Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception. 2018;97(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welti K, Manlove J. Unintended pregnancy in Delaware: estimating change after the first two years of an intervention to increase contraceptive access. March 14, 2018. Available at: https://www.childtrends.org/publications/unintended-pregnancy-delaware-estimating-change-first-two-years-intervention-increase-contraceptive-access. Accessed July 21, 2019.

- 33.Bullinger LR, Simon K. Prescription contraceptive sales following the Affordable Care Act. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23(5):657–666. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2680-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delaware Contraceptive Access Now. Evaluation of the Delaware Contraceptive Access Now Initiative. 2019. Available at: https://popcenter.umd.edu/delcaneval/evaluation. Accessed July 24, 2019.