Abstract

Objectives. To study the impact on mortality in Hawaii from the revoked state Medicaid program coverage in March 2015 for most Compact of Free Association (COFA) migrants who were nonblind, nondisabled, and nonpregnant.

Methods. We computed quarterly crude mortality rates for COFA migrants, Whites, and Japanese Americans from March 2012 to November 2018. We employed a difference-in-difference research design to estimate the impact of the Medicaid expiration on log mortality rates.

Results. We saw larger increases in COFA migrant mortality rates than White mortality rates after March 2015. By 2018, the increase was 43% larger for COFA migrants (P = .003). Mortality trends over this period were similar for Whites and Japanese Americans, who were not affected by the policy.

Conclusions. Mortality rates of COFA migrants increased after Medicaid benefits expired despite the availability of state-funded premium coverage for private insurance and significant outreach efforts to reduce the impact of this coverage change.

The benefits of the Medicaid program are well documented. The introduction of Medicaid in the 1960s and the expansion of Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have been shown to have reduced mortality.1,2 Given that providing Medicaid can save lives, it is important to ask what happens when coverage is scaled back. To answer this question, we studied a vulnerable group that lost standard Medicaid coverage in 2015 in the state of Hawaii.

Under the Compact of Free Association (COFA), citizens from 3 nation-states located in the Pacific Ocean (the Republic of Palau, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia) are given free entry into the United States. This is in exchange for US military access to their ocean territories and other benefits specified in the COFA. Under the compact, the United States pledged to support these nations in health and other social investment infrastructure, and COFA migrants are allowed unrestricted access to live and work in the United States. However, at any level of poverty, COFA migrants are not eligible for federal Medicaid coverage under the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.

States are left to decide if they wish to support the Medicaid enrollment of COFA migrants with limited means. In March 2015, following a legal decision, the state of Hawaii revoked coverage in the state Medicaid program for nonblind, nondisabled, nonpregnant COFA migrants aged 18 to 64 years. Instead, individuals in this group could obtain Medicaid-subsidized private insurance in exchanges established by the ACA under either of the 2 market-dominant health insurers in the state of Hawaii. Previous work has shown that health care utilization of COFA migrants declined as a result of the policy change.3 Our study goal was to consider the impact on mortality.

METHODS

We used mortality data from the Department of Health in the state of Hawaii. We computed the total number of deaths in each 3-month interval from March 2012 to November 2018 for 3 groups: migrants born in the Republic of the Marshall Islands or the Federated States of Micronesia (henceforth, COFA migrants), as well as 2 groups born in the United States: Whites and Japanese (henceforth, White or Japanese American). On average, there are 31 COFA deaths and close to 700 deaths among Whites and Japanese Americans (each), per quarter. To compute crude mortality rates, we employed estimated population counts from the American Community Survey.

A unit of observation was a year–quarter–ethnicity. We measured quarterly crude mortality rates starting in March 2012. This guarantees that one quarter ends in February 2015 and another begins in March 2015 so that the Medicaid expiration happened exactly between 2 quarters.

Before March 2015, all COFA migrants could enroll in Medicaid at any point in the year. From March 2015 onward, COFA migrants between the ages of 18 and 64 years could not enroll in Medicaid (unless they were blind, disabled, or pregnant) but had the option of enrolling in a subsidized private insurance plan available on the marketplaces set up by the ACA.

We calculated mortality rates across all ages in the analysis that follows, despite the fact that the Medicaid policy change officially only affected those aged 18 to 64 years. We did this because, according to some reports, there was confusion in the COFA community about who became ineligible for Medicaid in March 2015, which possibly resulted in underenrollment in Medicaid since then.4 Accordingly, the Medicaid expiration may have had an impact on the coverage of individuals aged younger than 18 years or older than 64 years, who may not have been aware that they were still eligible for Medicaid following the policy change. In fact, previous work has shown that emergency department utilization for children declined as a result of this policy change.3 It is also worth noting that, according to the American Community Survey, about 95% of all COFA migrants are aged younger than 65 years.

We employed a standard difference-in-difference (DiD) research design to estimate the impact of the Medicaid policy change on log mortality rates. To check for parallel trends across ethnicities before the policy change, we used an event–study analysis, controlling for ethnicity and year–quarter fixed effects. We estimated a linear model by using ordinary least squares, but results were similar when we used a Poisson or negative binomial model with number of deaths as our outcome.

RESULTS

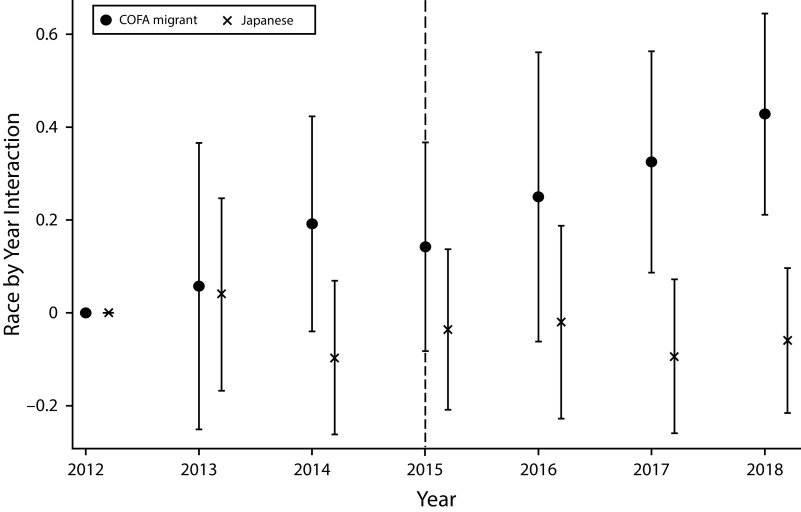

We found that mortality rates of COFA migrants increased relative to Whites after Medicaid benefits expired (Figure 1). In the years before the policy change, the changes in mortality rates relative to 2012 were similar for Whites and COFA migrants, offering support for the validity of the parallel trends assumption. Starting in March 2016, we see that COFA migrant mortality rates increased more than White mortality rates, but the difference in this change was not statistically significant. By 2017, the increase in mortality rates (from 2012) was 32% larger for COFA migrants than Whites (P = .009). By 2018, the increase was 43% larger for COFA migrants than Whites (P = .003). There were no statistically significant differences between quarterly mortality trends for Japanese Americans and Whites over this period, suggesting that our DiD estimates were not contaminated by omitted trends. We also estimated a simple DiD model, which focused on the interaction between COFA migrants and a post-2014 indicator (controlling for ethnicity and year–quarter fixed effects), and obtained an estimate of 0.21 (P = .003).

FIGURE 1—

Differences in the Change Across Racial/Ethnic Groups in Mortality Rates From March 2012 to November 2018 in Hawaii

Note. COFA = Compact of Free Association. This graph plots the coefficient estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) on COFA migrant × year and Japanese × year interactions in a regression that uses log mortality rate as the dependent variable and controls for ethnicity and year–quarter fixed effects. Sample size: 81 year–quarter–ethnicity observations. In a simple difference-in-differences model (with ethnicity and year–quarter fixed effects), the coefficient on the interaction between the COFA indicator and a post-2014 indicator was 0.21 (P = .003).

DISCUSSION

We found that the loss of traditional Medicaid benefits for COFA migrants was associated with higher mortality for this already vulnerable community. This decrease in benefits occurred despite the fact that low-income COFA households were eligible for state-funded premium coverage for private insurance, despite efforts by Medicaid to mitigate the impacts of the policy change, and despite outreach by the Medicaid program and community groups to try to reduce the impact of this coverage change.4

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

COFA migrants are a vulnerable population with health disadvantages relative to other groups in Hawaii.5 Notably, Hawaii’s COFA population is an understudied group that shares salient characteristics with other vulnerable US immigrant communities (e.g., limited English proficiency, poverty) who are often the targets of Medicaid reductions and other policy changes designed to cut state costs. As other states search for solutions to budget shortfalls or political imperatives by developing policies to reduce state Medicaid expenditures, information about Hawaii’s experience can provide translatable and timely lessons.

Our results also relate to recent experience in Spain, where the government ceased health coverage for undocumented immigrants in 2012.6 Using a similar DiD strategy, the authors estimated a 15% increase in mortality for undocumented immigrants (compared with natives), which is slightly smaller than our simple DiD estimate of a 21% increase in COFA mortality relative to Whites and Japanese Americans after 2015.

We provide strong evidence regarding the tradeoffs these cost-reduction policies had with the health effects on targeted populations. This has relevance to the design of health insurance coverage and the sharing of information about coverage changes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jonathan Skinner and workshop participants at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and the Asian Workshop on Health Economics and Econometrics in Otaru, Japan, for useful comments.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study did not involve the use of human participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodman-Bacon A. Public insurance and mortality: evidence from Medicaid implementation. J Polit Econ. 2018;126(1):216–262. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller S, Altekruse S, Johnson N, Wherry LR. Medicaid and mortality: new evidence from linked survey and administrative data. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2019.

- 3.Halliday TJ, Akee RQ, Sentell T, Inada M, Miyamura J. The impact of Medicaid on medical utilization in a vulnerable population: evidence from COFA migrants. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hofschneider A. Micronesians in Hawaii still struggle to get care. Honolulu Civil Beat. April 3, 2019. Available at: https://www.civilbeat.org/2019/04/micronesians-in-hawaii-still-struggle-to-get-health-care. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- 5.Hagiwara MK, Miyamura J, Yamada S, Sentell T. Younger and sicker: comparing Micronesians to other ethnicities in Hawaii. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(3):485–491. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juanmarti-Mestres A, Lopez-Casasnovas G, Vall-Castelló J. The deadly effects of losing health insurance. Barcelona, Spain: CRES-UPF; 2020.