Abstract

Latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to classify 394 adolescents undergoing substance use treatment, based on past year psychiatric symptoms. Relations between profile membership and (a) self-reported childhood maltreatment experiences and (b) current sexual risk behavior were examined. LPA generated three psychiatric symptom profiles: Low-, High- Alcohol-, and High-Internalizing Symptoms profiles. Analyses identified significant associations between profile membership and childhood sexual abuse and emotional neglect ratings, as well as co-occurring sex with substance use and unprotected intercourse. Profiles with elevated psychiatric symptom scores (e.g., internalizing problems, alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms) and more severe maltreatment histories reported higher scores for behavioral risk factors for HIV/STI exposure. Heterogeneity in psychiatric symptom patterns among youth receiving substance use treatment services, and prior histories of childhood maltreatment, have significant implications for the design and delivery of HIV/STI prevention programs to this population.

Keywords: Adolescent risk, Substance abuse, Psychiatric disorders, HIV, Sexual risk behavior, Child maltreatment, Person-centered, Sexual abuse, Neglect

Introduction

Childhood maltreatment, including physical, sexual or psychological abuse, has been identified as a general risk factor for a broad range of mental health problems and health risk behaviors in adolescence or young adulthood [1–4]. Adolescents receiving treatment services for alcohol and other drug use problems are more likely to endorse symptoms from multiple types of psychiatric disorders, compared to substance-using adolescents without a history of receiving substance use treatment. While existing research has documented patterns of co-occurring health risk behaviors associated with psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents [5], examination of associations among self-reported maltreatment histories, multivariate patterns of psychiatric symptoms and sexual risk behavior can enhance current understanding of heterogeneity in behavioral risk for exposure to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among youth undergoing treatment for substance use problems [6]. The present study examined antecedent or co-occurring self-reported maltreatment experiences associated with psychiatric symptom patterns, and their relations with sexual risk behavior among adolescents with clinically significant substance use problems.

Maltreatment Types as Risk Factors for Psychopathology

A growing body of research has documented the short- and long-term consequences of child maltreatment among children, adolescents and young adults [7, 8]. Research has provided evidence for relations between child maltreatment and the development of both internalizing and externalizing psychiatric disorders in these age groups [3, 8–10]. However, studies are inconsistent with regard to relations between maltreatment types and later psychopathology. Research has documented relations between emotional neglect and both externalizing [11] and internalizing problems [8, 12]. Similarly, studies of the impact of sexual abuse have documented associations with internalizing problems, such as mood and anxiety disorders, as well as the development of externalizing disorders, including substance use disorders (SUDs) [13, 14]. Finally, research has documented largely consistent relations between severe physical punishment in childhood and the development of externalizing problems [10, 15].

Documented heterogeneity in psychiatric outcomes related to childhood maltreatment experiences may be due to several factors such as maltreatment type (e.g., severe corporal punishment, neglect, sexual abuse), as well as the severity and chronicity of abuse experiences [8]. In addition, individual factors such as child IQ, social competence, perceptions of control, and attribution of blame, or contextual factors including environmental and peer supports moderate the impact of maltreatment experiences on developmental outcomes [16–18]. The above work has prompted increased research focus upon maltreatment contexts or specific competencies among maltreated youth [19]. However, unexplained variability in relations between adverse rearing environments and the development of psychopathology among youth, including substance abuse, is recognized as a significant prevention and clinical research challenge [20–22]. Youth with substance use problems often report past maltreatment experiences, broad ranges of problem behaviors, and meet diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders [11, 23]. Yet, it remains unclear what types of childhood maltreatment experiences are associated with specific psychiatric disorders or maladaptive health risk behaviors, including sexual risk behavior.

Maltreatment as a Risk Factor for Sexual Risk Behavior

Childhood maltreatment experiences have been found to be associated with adolescent sexual risk behavior in both community and clinical samples [22, 24, 25]. Tubman et al. [25] studied a community sample of young adults (N = 1,803) aged 18–23 years who were followed up from an earlier school-based study of risk and protective factors for substance use among early adolescents. Consistent with previous research with clinical and community samples [13, 26], Tubman et al. [25] found associations between lifetime histories of abuse experiences and young adults’ self-reported engagement in sexual risk behavior. However, while child sexual abuse (CSA) has been found to be associated with increased risk for sexual risk behavior participation across gender and all age strata, relations between other types of maltreatment and sexual risk behavior are not consistent [27, 28]. Brown et al. [27] described sexual behavior trajectories of abused and neglected youth (N = 816), ranging from 14 to 22 years old. This study documented that youth who reported two or more episodes of sexual abuse were more likely to experience early puberty, sexual intercourse, and pregnancy than a comparison group of youth (N = 727) who reported no history of abuse or neglect. After controlling for sexual abuse, however, neither physical abuse nor neglect appeared to have independent effects on participants’ self-reported sexual risk behavior.

Research on the long-term consequences of child maltreatment has focused largely on child sexual abuse rather than related adversities such as child neglect or physical abuse, thereby obscuring the relative importance of each predictor on long-term outcomes or the cumulative impact of multiple forms of maltreatment [17, 29, 30]. With regard to youth receiving substance abuse treatment services, little is known regarding how specific aspects of child maltreatment, i.e., its severity, or the experience of multiple forms, are related to discrete psychiatric sequelae, co-occurring psychiatric symptoms or patterns of co-occurring health risk behaviors. These research issues are significant given evidence that externalizing behaviors may play unique roles in promoting sexual risk behavior among youth with substance use problems [31]. Less consistent relations are reported between internalizing problems (i.e., anxiety and affective disorders) and sexual risk behavior, since internalizing problems may either provide protection from participation in sexual risk behavior or contribute to increased behavioral risk for HIV/STI exposure [32]. In the current study, the independent effect of childhood maltreatment types on psychiatric symptom patterns and multiple sexual risk behaviors was investigated in a sample of adolescents receiving substance use treatment services.

Based on a developmental psychopathology framework and recent developmental system theories [33], ontogenic development is a dynamic process characterized by sequential negotiations of stage-salient tasks which determine the emergence of either competence or incompetence. Exposure to severe adversities, such as child maltreatment, may act as significant impediments to the resolution of major stage-salient relational tasks. Subsequently, the individual’s adaptive development may be compromised not only with regard to a specific age-salient developmental task, but the resolution of subsequent developmental tasks may be compromised if they are predicated on the presence of distal competencies. Within a developmental psychopathology perspective, sequelae of child maltreatment have been conceptualized using an ecological-transactional developmental model [34]. According to this model, multiple inter- and intra-individual factors from different levels of analysis play dynamic roles in the underlying mechanisms promoting probabilistic sequelae of child maltreatment, including normative problem behaviors and health risk behaviors. More temporally distal analyses might examine the characteristics of children and parents and specific contextual features most predictive of maltreatment and subsequent sequelae of those adversities.

Similarly, attachment-oriented conceptual models posit that child maltreatment promotes maladaptive outcomes with regard to representational models of self and significant others [35]. Specifically, maltreatment experiences during childhood may lead to the development of negative representational models of the self (e.g., in terms of self-efficacy and self-capacities), as well as the self in relation to significant others and attachment figures, which may result in the development of specific forms of maladjustment, such as internalizing problems [16, 36], externalizing problems [10] and health-related risk behaviors [37]. Child maltreatment experiences challenge the acquisition of developmental milestones such as competencies associated with self concept or the perception of self in the context of social relationships. Available research suggests that experiences of severe adversity and subsequent deficits in interpersonal competencies may increase risk for the development of a range of maladaptive behaviors, including psychiatric problems and risk behaviors. These maladaptive outcomes, in turn, may increase risk for additional maltreatment experiences or sexual victimization [38, 39]. Future developmental studies can examine antecedent, multiply-determined processes most predictive of maltreatment experiences and subsequent deficits in attachment-related competencies.

Identifying Patterns of Risk

Sexual risk behaviors among adolescents are complex and better understood when studied as having multiple individual-level and contextual influences [40, 41]. Much progress has occurred during the past two decades to enhance the description and explanation of sexual risk behaviors in both community and clinical samples of adolescents. Particularly important analytic strategies have included structural equation modeling (SEM) to test causal models among distal and proximal influences on indicators of adolescent sexual behavior [42, 43]. However, other significant research questions related to the expression of sexual risk behavior by adolescents have received less research attention. Still rudimentary is our current understanding of the covariation of mental health problems and specific health risk behaviors among adolescents and significant distal influences on their co-patterning. Complementary analytic strategies, such as multivariate classification procedures may be especially appropriate for describing relations among psychiatric symptoms, sexual risk behavior, and the antecedent influences of childhood maltreatment experiences because they can be used to construct profiles of different types of people and the relation of these type profiles to outcomes, such as sexual risk behavior [44, 45].

Pattern-based classification strategies enable the application of multidimensional models (e.g., the ecological-transactional model) that emphasize the holistic integration of dynamic interactions between individuals’ behaviors and their environments [34, 46, 47]. Dimensional models derived from the classification of people into subtypes can be used to identify potential mechanisms influencing individuals’ maladaptive behaviors while recognizing the complex multivariate structure of influences on those behaviors (e.g., distal maltreatment contexts and the peer contexts in which sexual risk behavior occurs). Use of specific classification techniques to identify people with common developmental histories may enhance current understanding of the complex relations among childhood maltreatment experiences, adolescents’ reports of psychiatric symptoms and sexual risk behavior [47, 48]. The current study proposes: (1) to identify multivariate profiles based on adolescents’ psychopathology; (2) to examine self-reported childhood maltreatment experiences that are significant covariates of profile membership; and (3) to describe significant between-profile differences in multiple indices of sexual risk behavior.

The Current Study

Previous investigations of relations among maltreatment experiences, psychopathology, and health risk behaviors among adolescents (a) have not used multidimensional measures of child maltreatment and sexual risk behavior; (b) have often solely used variable-centered analytic strategies; and (c) have not incorporated measures of child maltreatment, psychopathology and sexual risk behavior into the same structural model. The purpose of the present investigation is to address this gap by testing multivariate relations among maltreatment experiences, psychopathology, and sexual risk behaviors using self-report measures via model-based classification analyses in a sample of youth receiving substance abuse treatment services. The current study is influenced in part by the developmental psychopathology research paradigm [34, 48]. First, a typology of self-reported psychiatric symptom patterns was generated, while taking into account between-group differences in self-reported childhood maltreatment experiences. This analytic strategy was used to describe heterogeneity in patterns of psychiatric symptoms and to improve current understanding of the multidimensional contexts in which psychopathology emerges. The second step involved the evaluation of associations between the resulting typology and behavioral indicators of risk for HIV/STI exposure. Specifically, linear regressions were conducted to evaluate multivariate relations among different psychopathology profiles and indices of sexual risk behavior.

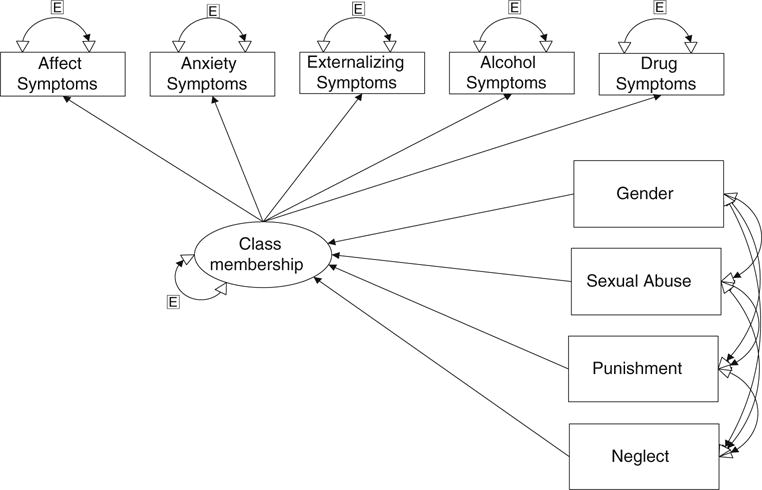

The specific research questions addressed were: (1) What latent psychiatric symptom patterns can be identified among adolescents receiving substance abuse treatment services?; (2) Is the extensiveness (i.e., severity, presence of multiple types) of child maltreatment experiences associated with specific patterns of psychiatric symptoms generated via LPA?; and (3) Do members of specific psychiatric symptom profiles report statistically significant differences in mean scores for specific indices of sexual risk behavior? Given the exploratory nature of LPA [49], no specific hypothesis was formulated regarding question 1. For question 2, we hypothesized that more severe scores for childhood maltreatment experiences would be associated with more extensive patterns of co-occurring psychiatric symptoms. For question 3, we hypothesized that more extensive patterns of psychopathology would be associated with higher scores for sexual risk behavior (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of latent profile analysis with psychiatric symptoms using maltreatment types and gender as predictors

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 394 adolescents, including 280 males (71.1%) and 114 females (28.9%), receiving substance use treatment services at two outpatient facilities in South Florida. The age of the participants ranged from 12 to 18 years old (M = 16.33 years; SD = 1.15). The ethnically diverse sample included 100 (25.4%) non-Hispanic White, 177 (44.9%) Hispanic, 81 (20.6%) African-American and 36 (9.1%) adolescents from other racial/ethnic groups. With regard to nativity, 328 (83.2%) of the participants were born in the United States, while out of the entire sample, 177 (44.9%) and 217 (55.1%) of their fathers and mothers (respectively) were born in the United States. The majority of the sample (n = 295, 74.8%) reported their father, mother, or both as primary caregiver(s). Over half of the participants (n = 208, 52.7%) reported repeating one or more school grades.

Procedure

Groups of adolescent clients were approached within one week of enrollment in outpatient substance abuse treatment services and invited to participate in the brief motivational HIV/STI risk reduction intervention. Clients were read the eligibility criteria, and if interested, were invited to contact a project staff member to have their eligibility confirmed and to begin the informed consent process. Each potential participant was screened for participation in sexual activity during the prior six months as an inclusion criterion. Parental consent was also required for study participation. Adolescents who, by case manager report, were actively suicidal or exhibited significant cognitive deficits or developmental delays were not eligible to participate due to ethical concerns about client safety and the cognitive capacities required for the psychotherapeutic intervention delivered in the treatment arm of the larger study. Adolescents who met inclusion criteria were assessed for DSM-IV psychiatric symptoms and were administered a battery of questionnaires before being enrolled in the HIV/STI risk reduction intervention. In the broader NIAAA-funded intervention program, participants completed a 60- to 90-min assessment focused on multiple variable domains including: Substance use, sexual risk behaviors, demographics, as well as putative mediators and moderators of intervention impact. Trained graduate students collected data using a structured interview protocol on laptop computers at the facilities in which clients were receiving substance abuse treatment services. Active consent was obtained from both adolescents and a primary caregiver via procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the sponsoring university. Participants were compensated $25.00 for completing the baseline assessment from which the data were drawn and analyzed for the present study.

Measures

Childhood Maltreatment Experiences

The child abuse and trauma scale [50] (CATS) is a 38-item self-report measure that was used to assess retrospectively maltreatment experiences during childhood or adolescence. The CATS contains three subscales that assess: neglect/negative home atmosphere, physical punishment, and sexual abuse. The CAT subscales were reported by Sanders and Becker-Lausen (1995) to have acceptable internal consistency for the total scale (α = .90), the neglect subscale (α = .86), the sexual abuse subscale (α = .76), and the punishment scale (α = .63). In addition, they reported significant test–retest reliability for CATS scales: the total scale (r = .89), as well as the neglect (r = .91), sexual abuse (r = .85), and punishment subscales (r = .71). The CATS demonstrates significant convergent validity with measures of similar abuse-related constructs [51]. In the current sample, the CAT subscales had acceptable internal consistency for the total scale (α = .93), and the neglect (α = .87), sexual abuse (α = .74), and the punishment subscales (α = .65).

DSM-IV Psychiatric Symptoms

Symptoms diagnostic of lifetime and past year DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses were assessed via the brief Michigan version of the composite international diagnostic interview [52] (CIDI-UM). The CIDI-UM is a comprehensive, structured diagnostic interview developed by the World Health Organization, based in part on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule [53]. The CIDI is administered by trained lay interviewers as a means to assess disorders defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) of the American Psychiatric Association (1994). The administration of the CIDI included skip patterns and probe questions. This instrument was developed to standardize the assessment of psychiatric disorders in community settings and samples [54]. The CIDI has excellent interrater reliability and good test–retest reliability [55], as well as sufficient validity based on concordance with clinical judgments and structured clinical interviews [56, 57]. Five aggregated symptom score categories, derived from the CIDI, comprised the component variables for latent profile analyses, including: (a) externalizing disorders––conduct disorder (CD)/oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), inattentive, hyperactive subtypes; (b) affective disorders––major depressive disorder, dysthymia; (c) anxiety disorders––generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, panic disorder; (d) alcohol abuse and dependence disorders; and (e) drug abuse and dependence disorders.

Timeline Follow Back-Sexual Risk Behavior (TLFB-SRB)

The standard TLFB instrument [58] was modified to collect data regarding adolescents’ self-reported sexual risk behavior, including unprotected intercourse, number of partners, and co-occurring substance use and sexual behavior. An adapted calendar format was used to assist in the recall of days when target sexual risk behaviors occurred. Participants completed the TLFB-SRB for the 180 days immediately prior to the baseline assessment. Similarly adapted TLFB calendar methodology has been used in published research to assess sexual risk behavior in persons with substance use problems, such as adult men who have sex with men [59] and psychiatric inpatients [60] with adequate reliability and validity. Carey et al. [60] concluded that empirical evidence supported the feasibility, reliability and validity of the TLFB for the assessment of sexual risk behavior. Furthermore, the reliability of TLFB methodology was supported for the collection of sexual risk behavior data among college women over a 1-week span, and in particular for low frequency behaviors [61].

Several additional items were used as indicators of sexual risk for HIV/STI exposure. Participants were asked to report their total number of sex partners during the previous six months. In addition, participants were asked to report how often during the past six months they or a partner (a) drank alcohol before or during sex or (b) used any illicit drugs before or during sex. These last two items used the response formats: always (5), usually (4), sometimes (3), rarely (2), or never (1). These items were included because they are recognized risk factors for HIV/STI exposure [62].

Data Analytic Plan

Latent profile analysis [63] was used to investigate the research questions outlined above (Fig. 1). LPA belongs to a family of model-based classification methods that stand in contrast to non-model based classification methods, such as K-means clustering (see [64] for a discussion of these differences). Patterns of psychiatric symptoms were identified from five CIDI-generated continuous variables (i.e., standardized anxiety, affective, externalizing, drug use, and alcohol use symptoms) that were used as observed variables regressed onto a categorical latent factor. Three latent profiles were identified representing discrete subtypes of psychiatric symptom groups [65]. The three profiles were then regressed onto three dimensions of childhood maltreatment, as well as a range of demographic covariates. Finally, regression-based analyses were conducted to identify between-profile differences for five sexual risk behavior variables.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Missing data were minimal (i.e., less than 8%) for most variables, and were imputed using expectation–maximization (EM) based methods with importance re-sampling [66]. A multiple imputation approach was used with five imputation data sets generated by the computer program Amelia [67]. Parameter estimates and standard errors across the imputed data sets were estimated using the formulas in King et al. [66]. Missing data bias was not evident in the data. This was explored by computing a dummy variable for missing data for each variable and correlating these dummy variables with other variables in the model and with demographic variables. Outlier analyses were also undertaken. Non-model based analyses involved examination of leverage indices for continuous variables for each individual. Model-based analyses involved the use of ordinary least squares regression in a limited information estimation framework to examine standardized df-betas for each individual, each predictor, and the intercept. Identified outliers were checked for coding errors. Outliers from TLFB-SRB count data were winsorized at a criterion of two standard deviations above the mean [68]. Analyses were conducted both with and without the outliers and the conclusions were comparable. Analyses also indicated that several of the indicators were skewed and slightly kurtotic. To account for non-normality, a robust maximum likelihood estimator was used (the MLR estimator in MPlus, which uses a Huber–White algorithm [69, 70]).

Table 1 summarizes correlations among continuous variables (i.e., three self-reported maltreatment variables, five psychiatric symptom variables, and five indices of sexual risk behavior) and presents relevant means and standard deviations. Statistically significant correlation coefficients with P values less than .05 are noted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations among variables included in the structural model

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of partners | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5.00 | 7.57 |

| 2. Total sex episodes | .18** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 25.94 | 31.85 |

| 3. Total unpr. episodes | −.03 | .74** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12.41 | 23.86 |

| 5. Sexual abuse score | −.00 | .03 | .06 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.21 | .46 |

| 6. Punishment score | −.00 | −.01 | −.00 | .28** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2.51 | .73 |

| 7. Neglect score | −.03 | .09 | .10** | .44** | .50** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2.15 | .78 |

| 8. AA/AD sympt. | .04 | .11* | .08 | .22** | .16* | .26** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.55 | 2.23 |

| 9. DA/DD sympt. | .10* | .15** | .15** | −.06 | .04 | .18** | .45** | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4.50 | 3.51 |

| 10. Total anxiety symp. | .05 | .07 | .11* | .10 | .08 | .24** | .23** | .26** | – | – | – | – | – | 7.93 | 5.30 |

| 11. Total affect symp. | .11* | .07 | .10* | .21** | .19** | .45** | .40** | .36** | .48** | – | – | – | – | 3.00 | 4.01 |

| 12. Total exter. symp. | −.01 | .05 | .06 | .08 | .13* | .26** | .29** | .32** | .37** | .29** | – | – | – | 18.90 | 8.17 |

| 13. Sex w/co-occur Alc. | .16** | .14** | .17** | .10 | .05 | .06 | .36** | .32** | .16** | .18** | .23** | – | – | 2.06 | 1.11 |

| 14. Sex w/co-occur drug | .12** | .18** | .16** | .02 | .03 | .12* | .25** | .44** | .21** | .27** | .21** | .44** | – | 2.51 | 1.37 |

| 15. Age | .11* | .25** | .19** | −.18** | −.06 | −.02 | .02 | .21** | .05 | −.02 | .09 | .13* | .22** | 16.31 | 1.16 |

| 16. Gender | −.05 | −.02 | .09 | .41** | .10 | .40** | .18* | .08 | .19** | .34** | .02 | −.05 | .08 | – | – |

Note:

P <.05;

P <.01. AA Alcohol abuse symptoms, AD Alcohol dependence symptoms, DA Drug abuse symptoms, DD Drug dependence symptoms

Classification of Youth

Profile Solution Selection Process

The selection of a latent profile solution was based on both technical and interpretive criteria [49]. Table 2 summarizes the indices of model fit used to evaluate the competing solutions for the number of profile types, including the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the sample-size adjusted BIC (i.e., the adjusted BIC), and the entropy index, i.e., the average highest predicted probability of profile membership. These indices were examined with two competing goals in mind, i.e., maximizing the clarity of profile membership and keeping the model parsimonious. Low values for the AIC, BIC, and adjusted BIC indicated a well-fitting model [49]. To help determine the optimal number of profiles, relative fit indices such as the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test of model fit [70] and the parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT) [71] were examined, comparing the estimated model to a model with one fewer profile than the estimated model.

Table 2.

Model fit statistics for two-, three- and four-part latent class solutions

| Model | Lo-M-R. | P | PBLR-T | P | AIC | BIC | BIC-Adj. | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Class | 222.61 | .00 | 226.75 | .00 | 5039.37 | 5154.69 | 5062.67 | .930 |

| Three-Class | 159.28 | .26 | 162.24 | .00 | 4895.13 | 5046.22 | 4925.66 | .943 |

| Four-Class | 89.59 | .15 | 91.00 | .00 | 4821.88 | 5008.77 | 4859.64 | .953 |

Note: Lo-M-R Lo-Mendell-Rubin, PBLR-T Parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio-test, AIC Akaike information criterion, BIC Bayesian information criterion, BIC-Adj BIC sample size adjusted

The LPA results were exploratory in nature and no a priori assumptions were made about the structure or distribution of classes. Analogous to an exploratory factor analysis, no specific assumptions were made about the number of factors or how the items were related to the underlying factor(s). The LPA models were fit in a series of modeling steps, starting with the specification of a one class model (i.e., an independence model that models the observed means in the data). The number of classes was increased until there was no further significant improvement of the model. That is, adding another class resulted in very small (i.e., few adolescents belonged to the profile) and/or meaningless (i.e., conceptually unclear) classes and there was no empirical support for additional classes.

In the current classification, while the three- and four-profile solutions showed similar statistical advantages, the three-profile solution was favored due to statistical power and conceptual considerations. In terms of power, the four-profile solution sliced Class 2 (n = 64) by two cases, decreasing significantly power for subsequent analyses. Conceptually, slicing Class 2 by two cases did not indicate meaningful or robust differences in psychiatric symptom types in the two solutions. The resulting latent profile probabilities, based on the most likely latent profile membership, for a three-profile solution are presented in Table 3. These results revealed that the lowest average latent profile probability was .941 for members of Class 2, .981 for members of Class 3 and .983 for members of Class 1. These profile probabilities suggested that in any of the three generated profiles, more than 94% of the profile members were classified correctly.

Table 3.

Average latent class probabilities for the three-part latent class solution

| Latent Class | n | Proportion | Class 1 Probability | Class 2 Probability | Class 3 Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | 302 | .766 | .983 | .013 | .004 |

| Class 2 | 64 | .162 | .043 | .941 | .016 |

| Class 3 | 28 | .071 | .015 | .004 | .981 |

Note: N = 394

Mean psychiatric symptom scores for the three-profile solution are presented in Table 4. This table summarizes distinct multivariate patterns of self-reported psychiatric symptoms. Profile 1 (the Low Symptom Profile; n = 302) was characterized by low average symptom counts for all symptoms assessed. Compared to the other two profiles, Profile 2 (the High Alcohol Symptom Profile; n = 64) reported the highest average symptom counts for alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms. Members of the High Alcohol Symptom Profile also reported high average scores for both drug use and dependence symptoms and externalizing disorder symptoms. In contrast, Profile 3 (the High Internalizing Symptom Profile; n = 28) reported the highest mean scores for both anxiety disorder symptoms and affective disorder symptoms. Similar to the High Alcohol Symptom Profile, members of the High Internalizing Symptom Profile also reported high mean scores for both drug use and dependence symptoms and externalizing disorder symptoms. With regard to the gender composition of each profile, female adolescents were more prevalent [χ2(2, N = 394) = 18.7, P > .01] in the High Internalizing (50.0%), and the High Alcohol (45.3%) Symptom Profiles, compared to the Low Symptom Profile (23.5%). No significant between-profile differences in mean age were identified.

Table 4.

Mean scores for psychiatric symptoms for the three-part latent class solution

| Symptom category | Low symptom class

|

High alcohol class

|

High internalizing class

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 302)

|

(n = 64)

|

(n = 28)

|

||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Alcohol use | .62 | 1.03 | 5.64 | 1.62 | 2.09 | 2.00 |

| Drug use | 3.82 | 3.31 | 6.71 | 3.20 | 6.39 | 3.67 |

| Anxiety | 6.28 | 3.04 | 9.08 | 4.34 | 22.57 | 4.60 |

| Affective | 2.02 | 3.15 | 4.60 | 4.79 | 8.92 | 4.23 |

| Externalizing | 17.54 | .47 | 22.92 | 1.10 | 23.71 | 1.80 |

Note: M Mean, SD Standard deviation

Between-Profile Differences in Child Maltreatment Experiences

The three symptom pattern profiles that were identified via LPA were used to define a three category outcome variable which was then regressed, using multinomial logistic regression, onto the maltreatment scales including: Neglect/Negative Home Environment, Sexual Abuse and Physical Punishment. The data summarized in Table 5 show statistically significant differences in profile assignment for two of the three CATS maltreatment scale scores, i.e., for Sexual Abuse and Neglect/Negative Home Environment. Logistic coefficients associated with the pairwise comparisons of the LPA-defined categories showed that when comparing the Low Symptom Profile to the High Alcohol Symptom Profile, there was a statistically significant coefficient for Sexual Abuse, such that youth with higher sexual abuse scores were more likely to be classified into the High Alcohol Symptom Profile than the Low Symptom Profile. Similarly, the coefficient for Neglect/Negative Home Environment indicated that adolescents with higher neglect scores were more likely to belong to the High Alcohol Symptom Profile than the Low Symptom Profile. In addition, when comparing the Low Symptom Profile to the High Internalizing Symptom Profile, the coefficient for Neglect/Negative Home Environment indicated that youth with higher rates of neglect experiences were more likely to be assigned to the High Internalizing Symptom Profile.

Table 5.

Logit coefficients, estimated standard errors, and odds ratio for three-class model with maltreatment types as covariates

| Type | High internalizing versus high alcohol class†

|

High alcohol versus low symptom class†

|

Logit | SE | OR | OR CI 95% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logit | SE | OR | OR CI 95% | Logit | SE | OR | OR CI 95% | |||||

| SA | .285 | .216 | 1.330 | .870–2.032 | .326 | .165 | 1.387* | 1.005–1.915 | .041 | .216 | 1.043 | .629–1.446 |

| Neg | −.204 | .259 | .815 | .491–1.355 | .673 | .185 | 1.959* | 1.363–2.814 | .878 | .244 | 2.402* | 1.483–3.891 |

| P | .187 | .320 | 1.205 | .644–2.255 | −.122 | .180 | .885 | .622–1.260 | .308 | .268 | .735 | .805–2.301 |

Note: SA Sexual abuse, Neg Neglect/negative home environment, P Punishment;

P <.05, SE Estimated standard error, OR Odds ratio

Reference group

Differences in Sexual Risk Behavior Across the LPA-Generated Psychiatric Symptom Profiles

To evaluate between-profile differences across the five indices of sexual risk behavior, separate linear regression analyses were performed, regressing each sexual risk behavior onto the three profile types, dummy coded using two dummy variables. The Holm-Adjusted-Modified-Bonferroni method [72] was used to control family-wise error rates across the various contrasts. Table 6 summarizes between-profile differences in mean scores for the sexual risk behavior variables. The High Internalizing Symptom Profile reported significantly higher scores for co-occurring sex and alcohol use, co-occurring sex and drug use, and unprotected intercourse episodes than the Low Symptom Profile. The High Alcohol Symptom Profile reported significantly higher scores for co-occurring sex and alcohol use, as well as co-occurring sex and drug use compared to the Low Symptom Profile. No statistically significant between-profile differences were found between the High Internalizing Symptom and the High Alcohol Symptom Profiles on any of the five sexual risk behavior variables. To determine if child maltreatment predicted sexual risk behavior over and above the LPA categories, the regression analysis was repeated but included the three maltreatment variables as predictors. None of the regression coefficients for these added predictors were statistically significant.

Table 6.

Comparison of sexual risk behavior indices by profile membership

| SRB indices | M LSP | M ASP | M IntSP | 95% CI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSP Vs. ASP | LSP Vs. IntSP | ASP Vs. IntSP | ||||

| Alcohol and sex | 1.91 | 2.76 | 2.39 | .53–1.15* | .02–.47* | −.89–.5 |

| Drugs and sex | 2.38 | 3.12 | 3.28 | .42–1.11* | .15–.71* | −.46–.78 |

| Number of partners | 4.97 | 4.27 | 6.50 | −2.04–.69 | −.57–3.21 | −.57–6.92 |

| Total no. episodes | 24.17 | 32.76 | 32.43 | −.53–18.99 | −2.45–12.15 | −16.25–18.77 |

| Total unp. episodes | 11.05 | 15.48 | 21.20 | −2.50–14.69 | .172–11.22* | −7.72–19.53 |

Note:

Mean difference is statistically significant, P < .05; M Mean, LSP Low symptom profile, ASP Alcohol symptom profile, IntSP Internalizing symptom profile

Sample sizes for LSP = 302, for Asp = 64 and for IntSP = 28

Discussion

This study used LPA to identify patterns of psychiatric symptoms reported by a clinical sample of adolescents, supporting an emerging literature that has documented substantial heterogeneity in psychiatric symptoms in youth populations [6, 73, 74]. Significant psychiatric symptom heterogeneity was found in relation to maltreatment histories that may reflect the substance abuse treatment sample studied, the participants’ ages and gender, as well as the zero-tolerance policies of some referral sources (e.g., local school districts). For example, the finding that the largest class in the present sample was the Low Symptoms Profile is due in part to the young age of the participants, i.e., before the stabilization of substance abuse and other mental health problems, and the large number of referrals from public school settings to less intensive outpatient treatment. The current study also documented substantial diversity in both participants’ childhood maltreatment experiences, and their current sexual risk behaviors. Use of a multivariate classification strategy to study self-reported childhood adversities, psychopathology and current health risk behaviors permitted an examination of how variables differed across three empirically-identified subgroups within a substance use treatment sample [75]. The LPA also enhanced our current understanding of multiple determinants of adolescent psychiatric symptoms and vulnerability to health risk behaviors [69].

Previous research has suggested linkages between maltreatment histories and sexual risk behavior [23], however little has been done to examine these links in relation to co-occurring psychiatric symptoms, such as substance abuse and dependence symptoms. Elkington, Bauermeister and Zimmerman [76] recently reported that substance use mediated relations between psychological distress and sexual risk behavior and suggested two plausible explanations. Youth may use substances to manage the experience of psychological distress, or alternatively, the use of substances such as alcohol contributes to the onset of depression and anxiety. The findings from the current study are also congruent with hypotheses derived from Alcohol Myopia Theory. Specifically, the neurological effects of intoxication may facilitate participation in sexual risk behavior, through pharmacological effects associated with behavioral disinhibition. Specifically, alcohol intoxication’s impact upon individuals’ information processing abilities is posited by some to discourage reasoning regarding the long-term implications of risk behavior while allowing highly potent cues (e.g., sexual arousal) to continue being processed [77]. However, alcohol use-sexual risk behavior relations should be investigated from a multivariate framework as these relations are significantly influenced by additional factors such as personality variables, alcohol-sexual outcome expectancies or interpersonal competencies [78]. The results complement and expand upon research documenting relationships between childhood maltreatment and patterns of psychiatric symptoms during adolescence, including early onset alcohol use problems [79]. For example, youth with higher scores for sexual abuse experiences showed higher odds of being classified within the High Alcohol Symptom Profile, compared to the Low Symptom Profile. Youth reporting higher rates of child neglect were significantly more likely to be members of the High Internalizing Symptom Profile and the High Alcohol Symptom Profile than the Low Symptom Profile. These findings are consistent with existing studies linking childhood neglect to the development of externalizing [2, 11, 80] and internalizing problems [8, 16, 29]. The current study further highlights the importance of further examination in longitudinal studies of maltreated children of potential influences on the emergence of psychopathology in adolescence, including the acquisition of normative competencies and representational models of the self [33–35]. Contrary to existing research [10, 15], childhood physical punishment was not associated significantly with psychiatric symptom profile membership, potentially reflecting normative experiences of harsh or inconsistent parental disciplinary practices [81] in this sample.

With respect to the psychopathology-based risk factors, an LPA identified three types of profiles that are implicated in differential sexual risk behavior. Two relatively high risk profiles, the High Alcohol Symptom Profile and the High Internalizing Symptom Profile, showed significantly higher rates of sexual risk behavior (i.e., co-occurring sex and substance use, unprotected intercourse), compared to the more normative Low Symptom Profile. Compared to the Low Symptom Profile, adolescents in the High Internalizing Symptoms Profile reported higher rates of unprotected intercourse. Thus, in the current sample internalizing symptoms were associated with increased risk for HIV exposure, supporting previous research that documented such an association. These findings extend previous studies [76, 82] regarding behavioral risk for HIV/STI exposure among youth with substance use problems by identifying co-occurring patterns of psychiatric symptoms (i.e., internalizing or substance use problems), maltreatment experiences (in particular, sexual abuse and emotional neglect), and specific sexual risk behaviors. One application of these findings to substance use treatment settings would be to tailor treatment content based on screenings for previous maltreatment histories and current psychopathology when youth are initially admitted, in order to efficiently reduce risk for future HIV/STI exposure. Youth at high risk for HIV/STI exposure might then benefit from supplemental and more intensive treatments that address directly factors (emotional distress, motives for substance use) influencing sexual risk behaviors. Thus, information gathered at treatment intake could be used to tailor HIV prevention efforts selectively, in an effort to reduce adolescents’ vulnerability to HIV/STI exposure, at a point when there may be greater openness by clients to therapeutic behavior change efforts.

Although females comprised 23.9% of the sample, they were disproportionately represented in the High Internalizing Symptom Profile and the High Alcohol Symptom Profile. Gender was therefore controlled for in the analyses comparing the three profiles on sexual risk behavior variables. However, the overrepresentation of female youth in the two high symptom profiles raises compelling developmental and clinical questions. Our research suggests that female youth who report childhood maltreatment experiences are vulnerable to the development of internalizing and substance use problems, which may influence significantly participation in specific sexual risk behaviors. These finding are congruent with existing research that suggests links between child and youth sexual abuse and increased risk for substance use problems and sexual risk behavior among female youth [22, 28, 83]. Recent research suggests that females may experience distinct mechanisms influencing relations between child maltreatment and substance use problems [84]; suggesting important differentiation by gender in future applied developmental research, as well as selected prevention studies.

The current study built upon existing research by documenting that profiles of individuals defined by severe and extensive patterns of psychiatric symptoms also reported the highest mean scores for selected indices of sexual risk behavior [85, 86]. Differences in scores for sexual risk behaviors between the Low Psychiatric Symptom Profile and the two high symptom profiles may reflect specific patterns of psychiatric symptoms in the high symptom profiles, e.g., the combination of depression and anxiety symptoms manifested by the High Internalizing Symptom Profile or the high levels of alcohol problems reported by the High Alcohol Symptom Profile [82, 85]. Therefore, clinical practice with adolescent clients in these two small heterogeneous groups, designed to reduce behavioral risk for exposure to HIV/STIs, should focus on mechanisms influencing sexual risk behavior, especially those related to past maltreatment, existing protective competencies or current psychopathology. Potential mechanisms facilitating relations between childhood maltreatment and patterns of alcohol and other drug use in previous research include the use of maladaptive coping strategies to address ongoing trauma-related distress, sex-related anxiety, or to promote numbing and dissociation [87, 88]. Therefore, the between-profile differences in childhood experiences of sexual abuse and parental neglect may represent ongoing sources of distress that influence the expression of sexual behavior via maladaptive responses to earlier trauma [13, 76]. In addition, childhood maltreatment may be associated with deficits in specific competencies (e.g., self-efficacy) or attitudes about self-protective behaviors [89].

Limitations

The current study had several limitations that make conclusions tentative. First, the cross-sectional design of the study does not permit straightforward causal statements regarding relations among child maltreatment experiences, psychiatric symptoms, and behavioral indices for HIV/STI exposure. For example, developmentally antecedent child, parent and contextual influences on children’s maltreatment experiences were not included in the analyses presented here. Therefore, future developmental studies represent significant opportunities to model parent–child or individual-context interactions, the direction of those relations, and broader ranges of childhood adversities to improve current knowledge regarding relations between adolescents’ psychiatric symptoms and health risk behaviors. However, the child maltreatment experiences reported in the present study are likely to have preceded chronologically the other outcomes assessed. Second, skip patterns in the computerized form of the CIDI used in the current study would tend to generate conservative patterns of psychiatric symptoms since they are likely to miss subsyndromal symptoms of depression, substance use problems, and PTSD [90, 91]. This is likely to influence the classification of symptoms while possibly missing sources of impairment in a treatment sample. Third, the selection of the optimal profile solution remains tentative due to the exploratory nature of LPA and the outpatient composition of the current sample. Future research should be conducted with larger samples to identify additional relevant psychiatric symptom profiles for HIV risk reduction efforts among adolescents in substance use treatment. Despite these limitations, this study adds to the existing knowledge about the complex multivariate relations among self-reported child maltreatment, psychopathology and risk for HIV/STI exposure among youth with substance use problems. The current findings provide further support for tailoring the content or delivery of selected HIV/STI prevention efforts for adolescents in substance use treatment [92].

Acknowledgments

This work summarizes in part the first author’s dissertation research supported in part by a Dissertation Year Fellowship from the University Graduate School at Florida International University. The preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by NIAAA Grants R01 AA13369, R01 AA14322, and R01 AA13825.

References

- 1.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Sturge-Apple ML. Interactions of child maltreatment and 5-HTT and monoamine oxidase A polymorphisms: depressive symptomatology among adolescents from low-socioeconomic status backgrounds. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(4):1161–80. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(4):692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogosch AF, Oshri A, Cicchetti D. From child maltreatment to adolescent cannabis abuse and dependence: a developmental cascade model. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22(4):883–97. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: a 30-year follow-up. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):149–58. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(6):1224–39. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oshri A, Tubman JG, Wagner E, Morris SL, Snyders J. Psychiatric symptom patterns, proximal risk factors and sexual risk behaviors among youth in outpatient substance abuse treatment. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(4):430–41. doi: 10.1037/a0014326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(6):607–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manly JT, Kim J, Rogosch F, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children’s adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(4):759–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, Rutter M, Shearer C, Maughan B. Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31(3):211–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Taylor A. Physical maltreatment victim to anti-social child: evidence of an environmentally mediated process. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113(1):44–55. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knutson JF, DeGarmo D, Koeppl G, Reid JB. Care neglect, supervisory neglect, and harsh parenting in the development of children’s aggression: a replication and extension. Child Maltreat. 2005;10(2):92–107. doi: 10.1177/1077559504273684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valentino K, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL. Memory, maternal representations and internalizing symptomatology among abused, neglected and nonmaltreated children. Child Dev. 2008;79(3):705–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auslander WF, McMillen JC, Elze D, Thompson R, Jonson-Reid M, Stiffman A. Mental health problems and sexual abuse among adolescents in foster care: relationship to HIV risk behaviors and intentions. AIDS Behav. 2002;6(4):351–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bulik CM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Features of childhood sexual abuse and the development of psychiatric and substance use disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179(1):444–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nix RL, Pinderhughes EE, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS, McFadyen-Ketchum SA. The relation between mothers’ hostile attribution tendencies and children’s externalizing behavior problems: The mediating role of mothers’ harsh discipline practices. Child Dev. 1999;70(4):896–909. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Pathways from child maltreatment to internalizing problems: perceptions of control as mediators and moderators. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(4):913–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGee R, Wolfe D, Olson J. Multiple maltreatment, attribution of blame, and adjustment among adolescents. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(4):827–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schultz D, Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, Jaycox L. The relationship between protective factors and outcomes for children investigated for maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;63(10):684–98. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zielinski DS, Bradshaw CP. Ecological influences on the sequelae of child maltreatment: A review of the literature. Child Maltreat. 2006;11(1):49–62. doi: 10.1177/1077559505283591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briere J, Runtz M. Childhood sexual abuse: Long-term sequelae and implications for psychological assessment. J Interpers Violence. 1993;8(3):312–30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(1):6–20. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(5):711–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tubman JG, Oshri A, Taylor HL, Morris SL. Maltreatment clusters among youth in outpatient substance abuse treatment: co-occurring patterns of psychiatric symptoms and sexual risk behaviors. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(2) doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9699-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lodico MA, DiClemente RJ. The association between childhood sexual abuse and prevalence of HIV-related risk behaviors. Clin Pediatr. 1994;33(8):498–502. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tubman JG, Montgomery MJ, Gil AG, Wagner EF. Abuse experiences in a community sample of young adults: relations with psychiatric disorders, sexual risk behaviors, and sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;34(1–2):147–62. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000040152.49163.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elze DE, Stiffman AR, Doré P. The association between types of violence exposure and youths’ mental health problems. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 1999;11(2):221–55. doi: 10.1515/IJAMH.1999.11.3-4.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown J, Cohen P, Chen H, Smailes E, Johnson JG. Sexual trajectories of abused and neglected youths. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25(1):77–82. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malow R, Dévieux J, Lucenko BA. History of childhood sexual abuse as a risk factor for HIV risk behavior. J Psychol Trauma. 2006;3(1):13–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herrenkohl TI, Herrenkohl RC. Examining the overlap and prediction of multiple forms of child maltreatment, stressors, and socioeconomic status: a longitudinal analysis of youth outcomes. J Fam Violence. 2007;22(7):553–62. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodgers CS, Lang AJ, Laffaye C, Satz LE, Dresselhaus TR, Stein MB. The impact of individual forms of childhood maltreatment on health behavior. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(5):575–86. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timmermans M, van Lier PAC, Koot HM. Which forms of child/adolescent externalizing behaviors account for late adolescent risky sexual behavior and substance use? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(4):386–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tubman J, Windle M, Windle R. Cumulative sexual intercourse patterns among middle adolescents: Problem behavior precursors and concurrent health risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 1996;18(3):182–91. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00128-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottlieb G, Lickliter R. Probabilistic epigenesis. Dev Sci. 2007;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cicchetti D, Valentino K. An ecological transactional perspective on child maltreatment: failure of the average expectable environment and its influence upon child development. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology. 2nd. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 2006. (Risk, disorder, and adaptation). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Briere J, Rickards S. Self-awareness, affect regulation, and relatedness: differential sequels of childhood versus adult victimization experiences. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(6):497–503. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31803044e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal trajectories of self-system and depressive symptoms among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Dev. 2006;77(3):624–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J, Cicchetti D. Social self-efficacy and behavior problems in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(1):106–17. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melander LA, Tyler KA. The effect of early maltreatment, victimization, and partner violence on HIV risk behavior among homeless young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(6):575–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Child mental health problems as risk factors for victimization. Child Maltreat. 2010;15(2):132–43. doi: 10.1177/1077559509349450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooper ML. Toward a person X situation model of sexual risk-taking behaviors: illuminating the conditional effects of traits across sexual situations and relationship contexts. J Per Soc Psychol. 2010;98(2):319–41. doi: 10.1037/a0017785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kotchick BA, Shaffer A, Forehand R, Miller KS. Adolescent sexual risk behavior: a multi-system perspective. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;2(4):493–519. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.East PL, Khoo ST. Longitudinal pathways linking family factors and sibling relationship qualities to adolescent substance use and sexual risk behaviors. J of Fam Psychol. 2005;19(4):571–80. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Jaccard J, Lesesne C, Gonzalez B, Kalogerogiannis K. Family mediators of acculturation and adolescent sexual behavior among Latino youth. J Prim Prev. 2009;30(3–4):395–419. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bergman LR, Magnusson D. A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 1997;9(2):291–319. doi: 10.1017/s095457949700206x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Eye A, Bogat GA. Person-oriented and variable-oriented research: Concepts, results, and development. Merrill Palmer Q. 2006;52(3):390–420. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magnusson D, Stattin H. The person in context: a holistic–interactionistic approach. In: Lerner RM, Damon W, editors. Theoretical Models of Human Development. Mahwah: Wiley; 2006. pp. 400–64. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mun EY, von Eye A, Bates M, Vaschillo E. Finding groups using model-based cluster analysis: heterogeneous emotional self-regulatory processes and heavy alcohol use risk. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(2):481–95. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mun EY, Windle M, Schainker LM. A model-based cluster analysis approach to adolescent problem behaviors and young adult outcomes. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20(1):291–318. doi: 10.1017/S095457940800014X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nylund K, Asparouhov T, Muthen B. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(4):535–69. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanders B, Becker-Lausen E. The measurement of psychological maltreatment: early data on the child abuse and trauma scale. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19(3):315–23. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(94)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higgins DJ, McCabe MP. Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggress Violent Behav. 2001;6(6):547–78. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliffe KS. National institute of mental health diagnostic interview schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(4):381–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) Int J Method Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28(1):57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janca A, Robins LN, Cottler LB, Early TS. Clinical observation of CIDI assessments: an analysis of the CIDI field trials-Wave II at the St Louis site. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160(1):815–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.6.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). 1. History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(8):624–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Followback users’ manual for alcohol use. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Midanik LT, Hines AM, Barrett DC, Paul JP, Crosby GM, Stall RD. Self-reports of alcohol use, drug use, and sexual behavior: expanding the timeline follow-back technique. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59(6):681–9. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carey M, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, Weinhardt LS. Assessing sexual risk behaviour with the timeline followback (TLFB) approach: continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(6):365–75. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Durant LE, Carey MP. Reliability of retrospective self-reports of sexual and nonsexual health behaviors among women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(4):331–8. doi: 10.1080/00926230290001457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalichman S, Tannenbaum L, Nachimson D. Personality and cognitive factors influencing substance use and sexual risk for HIV infection among gay and bisexual men. Psychol Addict Behav. 1998;12(4):262–71. [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCutcheon AL. Basic concepts and procedures in single and multiple group latent class analysis. In: Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL, editors. Applied latent class analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 56–88. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Magidson J, Vermunt JK. Latent class models for clustering: a comparison with K-means. Can J Mark Res. 2002;20(1):36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nylund K, Bellmore A, Nishina A, Graham S. Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say? Child Dev. 2007;78(6):1706–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.King G, Honaker J, Joseph A, Scheve K. Analyzing incomplete political science data: an alternative algorithm for multiple imputation. Am Political Sci Rev. 2001;95:49–69. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Honaker J, Joseph A, King G, Scheve K, Singh N. Amelia: a program for missing data. Boston: Department of Government, Harvard University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tukey JW. The future of data analysis. Ann Math Stat. 1962;33(1):1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6th. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthén; 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lo Y, Mendell N, Rubin D. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88(3):767–78. [Google Scholar]

- 71.McLachlan GJ, Peel D. Finite mixture models. New York: John Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos V. Analysis of variance frameworks in clinical child and adolescent psychology: basic issues and recommendations. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31(1):130–46. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoffmann NG, Bride BE, MacMaster SA, Abrantes AM, Estroff TW. Identifying co-occurring disorders in adolescent populations. J Addict Behav. 2004;23(4):41–53. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Potter CC, Jenson JM. Cluster profiles of multiple problem youth: mental health problem symptoms, substance use, and delinquent conduct. Crim Justice Behav. 2003;30(2):230–50. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laursen B, Hoff E. Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill Palmer Q. 2006;52(3):377–89. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Psychological distress, substance use, and HIV/STI risk behaviors among youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(5):514–27. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9524-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45(8):921–33. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kalichman SC, Simbayi L, Jooste S, Vermaak R, Cain D. Sensation seeking and alcohol use predict HIV transmission risks: prospective study of sexually transmitted infection clinic patients, Cape Town, South Africa. Addict Behav. 2008;33(12):1630–3. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, McCutcheon VV, Nelson EC, Waldron M, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and the course of alcohol dependence development: findings from a female twin sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89(2):139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clark DB, Thatcher DL, Maisto SA. Supervisory neglect and adolescent alcohol use disorders: effects on AUD onset and treatment outcome. Addict Behav. 2005;30(9):1737–50. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bank L, Burraston B. Abusive home environments as predictors of poor adjustment during adolescence and early adulthood. J Community Psychol. 2001;29(3):195–217. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S, Buka S. Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):189–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Widom CS, Schuck A, White HR. An examination of pathways from childhood victimization to violence: the role of early aggression and problematic alcohol use. Violence Vict. 2006;21(6):675–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Does physical abuse in early childhood predict substance use in adolescence and early adulthood? Child Maltreat. 2010;15(2):190–4. doi: 10.1177/1077559509352359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Donenberg GR, Bryant FB, Emerson E, Wilson H, Pasch K. Tracing the roots of early sexual debut among adolescents in psychiatric care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(5):594–608. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046833.09750.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tubman JG, Gil AG, Wagner EF, Artigues H. Patterns of sexual risk behaviors and psychiatric disorders in a community sample of young adults. J Behav Med. 2003;26(5):473–500. doi: 10.1023/a:1025776102574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Grayson CE, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators between childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems in adult women. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(2):137–45. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tubman J, Langer L, Calderon D. Coerced sexual experiences among adolescent substance abusers: A potential pathway to increased vulnerability to HIV exposure. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2001;18(2):281–304. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Houck CD, Nugent NR, Lescano CM, Peters A, Brown LK. Sexual abuse and sexual risk behavior: beyond the impact of psychiatric problems. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(5):473–83. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Peters L, Issakidis C, Slade T, Andrews G. Gender differences in the prevalence of DSM-IV and ICD-10 PTSD. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):81–9. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500591X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wagner HR, Burns BJ, Broadhead WE, Yarnell KSH, Sigmon A, Gaynes BN. Minor depression in family practice: functional morbidity, co-morbidity, service utilization and outcomes. Psychol Med. 2000;30(6):1377–90. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Noar SM, Benac C, Harris M. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):673–93. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]