Since their discovery in 2006 (Takahashi and Yamanaka 2006, 663), the so-called induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have been touted as the ethical alternative to using human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) for regenerative medicine. Cells capable of differentiating into all cell types in the adult organism were initially obtained from differentiated adult cells using a combination of transcription factors: Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc or the OSKM cocktail (Takahashi and Yamanaka 2006, 664) by using retroviruses to carry them into a skin cell. These factors then reprogram the skin cell to the ESC stage of development (Vogel and Holden 2007, 1224). These reprogrammed cells have been called iPS cells.

There has been a rush to approve this reprogramming procedure by both Catholic ethicists and Church officials (Weiss 2007, A001; US Conference of Catholic Bishops [USCCB] 2007). The USCCB (2007) state “the goal sought for years through failed attempts at human cloning—the production of pluripotent stem cells that are an exact match to a patient—has been brought within reach by an ethical procedure”. One Catholic ethicist states “embryonic stem cells have no moral status” (Wade 2007). We have however expressed that caution is needed before openly accepting these new stem cell procedures (Burke, Pullicino, and Richard 2007, 204).

Several new methods for obtaining cells capable of differentiating into all cell types in the adult organism have been developed. We would here like to comment on a recent report (Y. Zheng et al. 2019, 421) providing a method to mass produce multiple human embryo-like cells (MPEC) from human ESCs or iPS cells. The researchers use a microfluidic device that allows multiple embryos to grow simultaneously in a culture medium. There has been a recent call to debate the ethics of embryo models from stem cells (Rivron et al. 2018, 183; Y. L. Zheng, 2016, 1277), and here, we examine the ethics of the MPEC procedure. We also give some methodological background that may assist in determining what procedures could potentially be ethical.

A careful examination of the MPEC procedure shows that the embryo-like structures produced in the procedure (from either ESCs or iPS cells) are ontologically indistinguishable from embryos. These embryos are prevented from reaching their full potential by depriving them of the extra-embryonic cells required for implantation into the uterus, and if they, along with the extra-embryonic cells, were implanted into a surrogate uterus, they could develop into a living human infant.

It has been shown (Wernig et al. 2007, 318) that iPS cells can be made to form complete organisms when given access to the cells, which form the placenta and umbilical cord. In fact, in mice, both late stage mouse embryos and live born mice have been produced using mouse iPS cells (Boland et al. 2012). If the same procedures were applied to human somatic cells, there is every reason to believe that human infants could be produced (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Production of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) mice. Left: iPSCs are injected into the blastocoel of a tetraploid blastocyst. Middle: Newborn iPSC mice are distinguished by pigmented eyes. Right: iPSC mouse at three weeks postdelivery. Source: Figure 4 from Boland et al., (2012).

Although ESCs and iPS cells are referred to scientifically as pluripotent, this term is misleading when used for ethical analysis. There are two definitions of totipotent: “capable of developing into a complete organism” or “differentiating into any of its cells or tissues” (Merriam Webster 2019). Both the ESC and the iPS cells are capable of differentiating into any of the organism’s cells or tissues and so fit the second definition. Therefore, they are totipotent and have the potential to form the live born individual (Wernig et al. 2007, 318). The ESCs, if given access to cells forming the placenta and umbilical cord, are therefore ontologically indistinguishable from the zygote, single cell embryo, as both can result in the formation of an embryo (Y. Zheng et al. 2019, 421) and a live animal (Wernig et al. 2007, 318). Wernig et al. conclude: “in-vitro reprogrammed iPSs are indistinguishable from those of ESCs.”

The fact that the ESC and iPS cells cannot form the trophoblast (TR) cells required for the formation of the placenta and umbilical cord means that by themselves, they cannot progress to formation of a live animal. However, if they are injected into a blastocyst or they are incorporated into a microfluidic device (Y. Zheng et al. 2019, 421), they develop, and if successfully implanted in the uterus of a surrogate, they could subsequently become live born individuals. The lack of their own TR does not stop the ESCs and iPS cells being capable of developing into a live born individual when structures formed by the TRs are supplied, just as an embryo needs a uterine environment that it does not supply itself. Because the extra-embryonic TR cells and their products, the placenta and umbilical cord, are not part of the embryo by definition (Merriam Webster 2019), ESCs and iPS cells are ontologically the same as embryos.

An earlier reprogramming procedure called altered nuclear transfer (ANT) did essentially the same thing as this new reprogramming procedure. In ANT, the gene required for production of the TR cells is knocked out in the adult somatic cell nucleus. The nucleus of the adult somatic cell is then injected into an enucleated egg cell. In this case, the reprogramming is done by the egg cell. What is produced is an ESC, which cannot develop to its full potential because it lacks a placenta and umbilical cord that are necessary for implantation. This is the exact same result as the new MPEC reprogramming procedure. However, the ANT procedure was not approved by the USCCB and was condemned by their ethicist saying, “a short lived embryo is still an embryo” (Holden and Vogel 2004, 2175). It was condemned by scientists who said ANT was “creating a crippled embryo for purposes of exploitation” (Holden and Vogel 2004, 2175). Another reprogramming procedure called oocyte-assisted reprogramming (OAR) used a similar procedure except that the gene for NANOG was inserted into the adult somatic cell nucleus. OAR also results in an embryo whose ability to develop past a certain stage is limited. The morality of ANT/OAR procedures has been previously reviewed (Burke, Pullicino, and Richard 2007, 204). It should be noted that one of the new reprogramming procedures also uses the NANOG gene (Vogel and Holden 2007, 1224), and the other procedure screens for NANOG positive iPS cells to detect the ESC, which can form the entire organism.

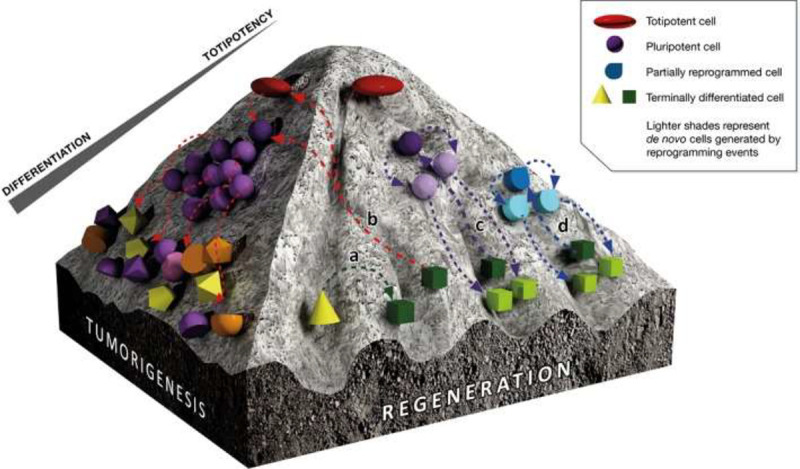

Recently, lineage-restricted transcription factors and micro-ribonucleic acids have been used to directly reprogram one somatic cell to another in another process called direct cellular reprogramming/trans-differentiation (Srivastava and DeWitt 2016, 1386). This “second generation” of cellular reprogramming does not entail intermediary formation of an iPS cell and directly converts one somatic cell type to another. Trans-differentiation appears fundamentally different to the techniques mentioned above, and in our view, it could be an ethical procedure as pluripotency is not attained (see [a, d] in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Tumorigenesis versus regeneration in cell reprogramming. The darker, left side of the figure shows that when there is sustained reprogramming to “pluripotency,” there is a tendency to tumorigenesis (teratoma formation) (b) as this is effectively cloning. Where reprogramming is only partial or direct (lighter, right side of figure) between cell types (trans-differentiation) (a), or partial (d), the pluripotent state is not attained, and there is no ontological equivalence with an embryo. Source: Taken from de Lázaro, Cossu, and Kostarelos (2017, 734).

In conclusion, we would like to highlight two major ethical implications: first, the production of iPS cells is not morally neutral. Y. Zheng et al. (2019) show that the iPS cell has the same capacity to develop into an embryo as an ESC (p. 421; when structures formed by the TR cells are supplied), and they are therefore ontologically and morally the same. Y. L. Zheng (2016, 1277) says that there should be limits on the use of human iPS cells. A recent EuroStemCell review (Hermerén 2018) says that if human ESCs have a special moral status because they can contribute to a human embryo under appropriate conditions, then human iPS cells should have the same special moral status if they, too, can contribute to a human embryo. Partially reprogrammed cells (see Figure 2) do not have the same ethical issue as they do not go through a pluripotent stage.

Second, the newly established ability to scale production of multiple embryos from iPS or ESCs breaks new ethical ground. Y. Zheng et al. (2019) are careful to call their cell colonies “embryo-like” but the possibility that their technique could in future be adapted to clone multiple humans cannot be ignored.

Biographical Notes

Patrick Pullicino, MD, PhD, is a recently ordained Catholic priest in the Archdiocese of Southwark, London, UK and Chaplain at St George’s University Hospital, London. He is a retired neurologist and professor of Clinical Neurology at the University of Kent. Prior to that he was professor and Chairman of the Department of Neurology and Neurosciences, UMDNJ, New Jersey. His main bioethics interests are in the ethics of end of life care and in the medical and societal effects of contraception.

Edward J. Richard, MS, VF, JD, DThM, is a LaSalette Missionary, Pastor, and Vicar Forane in the Diocese of Lake Charles, La. He is a consultant to a number of dioceses on Medical-Moral issues. He is a member of the Faculty of the St. Paul VI Institute Education Program, a member of the Board of Directors of Fertility Care Centers of America, and former Vice-Rector and professor of Moral Theology at Kenrick-Glennon Seminary.

William J. Burke, MD, PhD, is Emeritus professor of Neurology at St Louis University. He is an academic clinical neurologist and basic neuroscientist. His main laboratory research interests are mechanisms of cell death in Alzheimers and Parkinson diseases and disease modifying treatment strategies for Parkinson disease. His main bioethics interests are in stem cells, cloning and low awareness states.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Patrick Pullicino, MD, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6865-8333

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6865-8333

William J. Burke, MD, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9101-4306

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9101-4306

References

- Boland Michael J., Hazen Jennifer L., Nazor Kristopher L., Rodriguez Alberto R., Martin Greg, Kupriyanov Sergey, Baldwin Kristin K. 2012. “Generation of Mice Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells.” Journal of Visualized Experiments 69:e4003 doi: 10.3791/4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke William J., Pullicino Patrick, Richard Edward J. 2007. “The Biological Basis of the Oocyte Assisted Reprogramming (OAR) Hypothesis: Is It an Ethical Procedure for Making Embryonic Stem Cells?” The Linacre Quarterly 47:204–12. [Google Scholar]

- de Lázaro Irene, Cossu Giulio, Kostarelos Kostas. 2017. “Transient Transcription Factor (OSKM) Expression is Key towards Clinical Translation of In Vivo Cell Reprogramming” EMBO Molecular Medicine 9:733–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermerén Göran. 2018. “Ethics and Reprogramming: Ethical Questions after the Discovery of iPS Cells.” https://www.eurostemcell.org/ethics-and-reprogramming-ethical-questions-after-discovery-ips-cells.

- Holden Constance, Vogel Gretchen. 2004. “A Technical Fix for an Ethical Bind?” Science 306:2174–76. doi: 10.1126/science.306.5705.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam Webster Medline Plus Medical Dictionary. 2019. “Totipotent; Extraembryonic.” http://c.merriam-webster.com/medlineplus/totipotent.

- Rivron Nicolas, Pera Martin, Rossant Janet, Arias Alfonso Martinez, Zernicka-Goetz Magdalena, Fu Jianping, Brink Susanne van den, et al. 2018. “Debate Ethics of Embryo Models from Stem Cells.” Nature 564:183–85. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-07663-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava Deepak, DeWitt Natalie D. 2016. “In Vivo Cellular Reprogramming: The Next Generation.” Cell 166:1386–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Kouhei, Yamanaka Shinya. 2006. “Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors.” Cell 126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USCCB (US Conference of Catholic Bishops Department of Communications). 2007. “Women for Faith and Family 2007. Stem Cell Breakthrough Advances Science without Ethical Landmines, Says Cardinal.” http://archive.wf-f.org/USCCB_1107StemCells.html.

- Vogel Gretchen, Holden Constance. 2007. “Field Leaps Forward with New Stem Cell Advances.” Science 318:1224–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade Nicholas. 2007. “Biologists Make Skin Cells Work Like Stem Cells.” New York Times, June 6, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Rick. 2007. “Stem Cell Work Hits Milestones.” St Louis Post-Dispatch, November 21: A001. [Google Scholar]

- Wernig Marius, Meissner Alexander, Foreman Robert, Brambrink Tobias, Ku Maurice, Hochedlinger Konrad, Bernstein Bradley E., Jaenisch R. 2007. “In Vitro Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into a Pluripotent Es-cell-like State.” Nature 448:318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Yi, Xufeng Xue, Shao Yue, Wang Sicong, Esfahani Sajedeh Nasr, Li Zida, Muncie Jonathon M., et al. 2019. “Controlled Modeling of Human Epiblast and Amnion Development Using Stem Cells.” Nature 573:421–25. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1535-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. L. 2016. “Some Ethical Concerns about Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells.” Science and Engineering Ethics 22:1277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]