Summary

Real-world practice patterns of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) among gastroenterologists are not well-described. The aim is to describe practice patterns of EoE diagnosis and management and assess concordance with consensus guidelines. We conducted a cross-sectional online survey of gastroenterologists in the USA using Qualtrics, which was dispersed through the North Carolina Society of Gastroenterology (NCSG) and the American College of Gastroenterology member listservs. A similar survey was sent to NCSG members in 2010 and responses were compared in a subanalysis. Of 240 respondents, 37% (n = 80) worked in an academic setting versus 63% (n = 138) community practice setting. Providers saw a median of 18 (interquartile range 2–100) EoE patients annually and 24% (n = 52) were ‘very familiar’ with EoE guidelines. A proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) trial was required by 37% of providers prior to EoE diagnosis. In total, 60% used a ≥15 eosinophils per high-power field cut point for diagnosis and 62% biopsied from the proximal and distal esophagus on initial exam. Only 12% (n = 28) followed EoE diagnosis guidelines. For first-line treatment, 7% used dietary therapy, 32% topical steroids, and 61% used PPIs; 67% used fluticasone as first-line steroid; 41% used maintenance steroid treatment in responders. In the NCSG cohort, a higher proportion in 2017 followed guideline diagnosis recommendations compared with 2010 (14% vs. 3%; P = 0.03) and a higher proportion used dietary therapy as first-line treatment (13% vs. 3%; P = 0.046). There is variability in EoE practice patterns for EoE management, with management differing markedly from consensus guidelines. Further education and guideline dissemination are needed to standardize practice.

Keywords: clinical practice guideline, eosinophilic esophagitis, management, practice pattern

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, immune/ antigen-mediated disease characterized by esophageal dysfunction and eosinophilic inflammation limited to the esophagus.1 Though EoE is a rare condition overall, its incidence and prevalence has increased over the last several decades.2,3 As the understanding of basic immune mechanisms,4–6 natural history,2,7 clinical phenotypes,8–10 and diagnostic and treatment approaches have evolved over time,11–14 so too have expert guidelines regarding the diagnosis and management of EoE since initial consensus recommendations were published in 2007.1,15–18

Initial guidelines recommended diagnosing EoE when at least one biopsy, from the proximal and distal esophagus, demonstrated 15 or more eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) in a patient with esophageal symptoms not attributed to an alternative cause of eosinophilia, if eosinophilia persisted after a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) trial.15,17,18 This recommendation was based on the concept that both gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) had to be excluded prior to EoE diagnosis. In this setting, PPI use was a diagnostic test, whereas EoE treatment strategies included swallowed topical corticosteroids and dietary elimination. However, as new data emerged over time, a nuanced interrelationship between EoE, GERD, and PPI-REE was appreciated, and it became clear that a PPI trial was not needed for EoE diagnosis. Therefore, the most recent consensus guidelines eliminated PPI use from the diagnostic algorithm and repositioned PPIs as a potential first-line treatment.1,18,19

In the setting of these evolving guidelines, real-world practice patterns concerning the diagnosis and management of EoE remain poorly characterized. Three years after the initial expert consensus guidelines were published in 2007, practice patterns among gastroenterologists in the USA were highly variable, with poor adherence to the guidelines.20 While some data suggested that over time a higher proportion of studies adhered to diagnostic criteria described in the guidelines,19 other recent surveys in different adult and pediatric provider populations demonstrate continued practice pattern variability, poor guideline adherence, and low rates of shared decision-making with patients in clinical management.21–23 The understanding of practice patterns is essential to prioritize training efforts, identify continuing education needs, assess dissemination and implementation efforts, and improve quality and high-value care regarding EoE diagnosis and management.

Therefore, we aimed to assess practice patterns regarding the diagnosis and management of EoE, and their concordance with clinical practice guidelines, in a nationwide sample of academic and community gastroenterologists. In addition, we aimed to determine whether there was a change in practice patterns in a cohort of gastroenterologists in North Carolina who were previously administered this survey in 2010.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

We conducted an online cross-sectional survey developed and self-administered through the Qualtrics (Provo, Utah, USA) web-based platform. The survey was dispersed through membership electronic mailing lists of both local and national professional gastroenterologic societies in the USA including the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the North Carolina Society of Gastroenterology (NCSG), which comprised of adult and pediatric gastroenterologists from both academic and community practices. This study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board (IRB). All respondents consented to study participation.

Survey instrument and administration

The survey was designed to assess EoE practice patterns of gastroenterologists and concordance with the ACG17 and the European EoE guidelines.18 The survey comprised of 35 questions over four categories: (i) EoE symptoms and endoscopic features; (ii) EoE diagnosis; (iii) EoE treatment; and (iv) respondent and practice characteristics (see Supplementary Appendix A1). No individual participant identifiers were collected. We utilized the same questions and survey structure to a previously administered survey in 2010 assessing EoE practice patterns to gastroenterologists in North Carolina via the NCSG email listserv.20 Prior to dissemination, survey questions were piloted among five gastroenterologists to assess for comprehensibility and appropriateness of survey content.

We administered the online survey over a 3-month period in 2018 prior to the dissemination of the latest updated EoE consensus guidelines in 2018, which for the first time recommended PPIs as first-line treatment for EoE rather than the previously recommended high-dose PPI trial to exclude PPI-REE prior to the diagnosis of EoE.1 Personalized IRB-approved email invitations were sent to participants that contained individualized links to the online survey through Qualtrics. After the initial email, two follow-up email reminders were sent. The survey could only be completed once. All responses were anonymous.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize distributions of responses. Specifically, we calculated means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical data. Bivariable analyses (two-sample t-test, Pearson’s chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate) were used to compare respondent characteristics and practice patterns between academic and community gastroenterologists. As part of our sampling frame was identical to our prior practice pattern survey (members of the NCSG), we also used bivariable analyses to compare practice patterns between 2010 and 2017. To assess how a respondent personally reached a diagnosis of EoE, we asked, ‘Which of the following do you require to make the diagnosis of EoE?’ The respondent selected the answer(s) they felt were most appropriate from a list of criteria including: consistent symptoms, positive endoscopy findings, positive biopsy findings, no clinical response to a PPI trial, no histologic response to a PPI trial, and negative pH and testing (see Supplementary Appendix A1). Individual components were combined for the analysis. Tests of significance were two-tailed and an alpha value <0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed with STATA software, version 14.0 (College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Of eligible gastroenterologists to whom the survey was administered, 240 physicians had adequate survey completion data (Table 1). All but one respondent (99.6%) reported having cared for a patient with EoE, with a median estimate of 18 patients per month (interquartile range [IQR] 2–100) seen in practice. Of all respondents, 43 (20%) reported specialization in esophageal disease. Mean years in clinical practice was 19 (SD = 12). Most respondents practiced in a community setting (63%) versus an academic setting (37%). There was balance among urban versus suburban practices (44% vs. 45%), with 11% of respondents reporting practicing in a rural region. Only 54 (24%) respondents reported being ‘very familiar’ with EoE consensus guidelines.

Table 1.

Overall sample characteristics

| All respondents (n = 240) | |

|---|---|

| Years in practice, mean ± SD | 19 ± 12 |

| Specialization in esophageal disease, n (%) | 43 (20) |

| Practice setting, n (%) | |

| Academic | 80 (37) |

| Community | 138 (63) |

| Region of practice, n (%) | |

| Urban | 94 (44) |

| Suburban | 97 (45) |

| Rural | 24 (11) |

| ‘Very familiar’ with EoE consensus guidelines, n (%) | 52 (24) |

| EoE patients per month, median, IQR | 18 (2–100) |

EOE, eosinophilic esophagitis; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Symptoms and endoscopic features of EoE

Dysphagia (98% of respondents) and food impaction (92%) were the most common symptoms considered and abdominal pain (8%), anemia (4%), and hematemesis (4%) were the least considered symptoms when making the diagnosis of EoE. Other common symptoms considered included chest pain (58%), refractory reflux (48%), heartburn (39%), odynophagia (38%), and regurgitation (26%). In terms of endoscopic findings, esophageal rings (97%) and linear furrows (95%) were the most common endoscopic features, which respondents associated with the diagnosis of EoE, followed by white plaques/exudates (95%), narrow caliber esophagus (81%), mucosal tears after passing the endoscope (80%), and esophageal stricture (70%). Only 29% used the EoE endoscopic reference system to grade endoscopic findings in EoE.11

EoE diagnosis

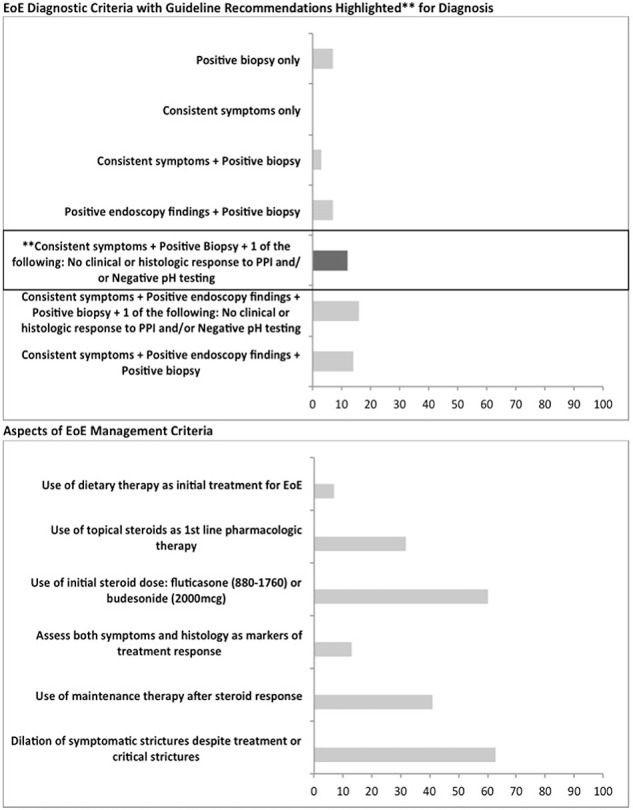

Only 12% (n = 28) of respondents used all three EoE diagnostic criteria in the guideline published at the time of this study to diagnose EoE (consistent symptoms of esophageal dysfunction; an esophageal biopsy specimen with at least 15 eos/hpf; and inadequate clinicopathologic response to a PPI and/or negative pH testing15) (Fig. 1). Academic gastroenterologists were more likely to adhere fully to guidelines than those in community practice (21% vs. 7%; P ≤ 0.01, Table 2). Of all respondents, none reported diagnosing EoE solely based on consistent clinical symptoms and 17% used limited criteria for diagnosis—specifically, 7% only required a positive biopsy, 3% required both consistent symptoms and a positive biopsy, and 7% required both positive endoscopic findings and a positive biopsy without clinical symptoms. Overall, 59% required at least one positive endoscopic feature to diagnose EoE. About one-third (37%) of respondents required a PPI trial prior to the diagnostic endoscopy (61% academic vs. 20% community; P ≤ 0.01). Of those that required a PPI trial, 72% recommended twice daily therapy and a majority (58%) required the trial be at least 8 weeks in duration (Table 2). Two percent required a negative pH probe prior to EoE diagnosis.

Fig. 1.

Concordance between eosinophilic esophagitis (EOE) practice patterns and consensus guidelines.

Table 2.

EoE practice patterns based on practice setting

| Academic practice (n = 80) | Community practice (n = 138) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis of EoE made per consensus guidelines: consistent symptoms + positive biopsy + one of the following: no clinical response to a PPI, no histologic response to a PPI, and/or negative pH testing (%) | 21 | 7 | <0.01 |

| Biopsies from proximal and distal esophagus (%) | 91 | 98 | 0.09 |

| Place biopsies from different locations in different jars (%) | 82 | 64 | <0.01 |

| Use of cut point of ≥15 eos/hpf for diagnosis (%) | 76 | 49 | <0.01 |

| Biopsies from stomach/duodenum on initial exam if symptomatic or (+) endoscopic abnormalities (%) | 39 | 49 | 0.16 |

| Require PPI trial prior to EoE diagnosis (%) | 61 | 20 | <0.01 |

| Use of dietary therapy as initial treatment for EoE (%) | 11 | 4 | 0.05 |

| Use of topical steroids as first-line pharmacologic therapy (%) | 39 | 28 | 0.11 |

| Use of fluticasone for as first-line steroid therapy (%) | 53 | 77 | <0.01 |

| Use of initial steroid dose: fluticasone (880–1760) or budesonide (2000 mcg) (%) | 43 | 54 | 0.03 |

| †Assess both symptoms and histology as markers of treatment response (%) | 19 | 15 | 0.44 |

| †Use of maintenance therapy after steroid response (%) | 36 | 44 | 0.22 |

| †Dilation of symptomatic strictures despite treatment or critical strictures (%) | 68 | 60 | 0.28 |

†Conditional recommendation.

EOE, eosinophilic esophagitis; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor.

Regarding biopsy procurement, guidelines recommend obtaining two to four mucosal biopsy specimens of the proximal and distal esophagus.15 Overall 86% of gastroenterologists obtained biopsies from both the proximal and distal esophagus with no differences between academic and community gastroenterologists; P = 0.09. A median of three biopsies (IQR 2–4) were typically obtained at EoE diagnosis. Academic gastroenterologists were more likely to place biopsies from different locations in different jars (82% vs. 64%; P < 0.01; Table 2). Less than half reported obtaining biopsies from the stomach and duodenum in symptomatic patients.

The majority of respondents (59%) used a cut point of ≥15 eos/hpf on their esophageal mucosal biopsy specimens for histopathologic diagnosis, although academic gastroenterologists were more likely to use this diagnostic threshold than community gastroenterologists (76% vs. 49%; P < 0.01; Table 2).

EoE management

Of first-line treatments selected by respondents, 7% used dietary therapy (11% academic vs. 4% community; P = 0.05), 32% used topical corticosteroids (39% vs. 28%; P = 0.11), 33% used twice a day PPI, and 28% used daily PPI. Use of combination therapy was not assessed.

Of those who used topical corticosteroids as first-line treatment, 67% used fluticasone, with community gastroenterologists more likely to recommend fluticasone opposed to budesonide than those in academic settings (77% vs. 54%; P > 0.01). Only 35% used the recommended total daily dose of budesonide of 2 g daily in adults compared with 72% who used the recommended daily fluticasone dosage of 880–1760 mcg. Those in community practice were more likely to initiate high-dose topical corticosteroids (fluticasone 880–1760 mcg daily or budesonide 2 g daily) as first-line treatment than academic gastroenterologists (54% vs. 43%; P = 0.03). A majority (59%) of all respondents did not use maintenance steroid treatment in initial responders. Additional conditional recommendations such as periodic assessment of both symptoms and histology to monitor treatment response was performed by 16% of respondents, whereas 63% dilated critical or symptomatic strictures (68% academic setting vs. 60% community setting; P = 0.28).

Longitudinal trends in practice patterns in North Carolina

The NCSG cohort comprised of 38 respondents in 2010 and 65 respondents in 2017. A higher proportion in 2017 followed guideline recommendations for diagnosis compared to 2010 (14% vs. 3%; P = 0.03) (Table 3). There was an increase in use of dietary elimination as initial treatment (13% vs. 3%) and a decline in the use of topical corticosteroids as first-line pharmacologic treatment (39% vs. 56%; P = 0.04). Overall, a majority continued to use high-dose topical steroids as first-line treatment (fluticasone 880–1760 mcg daily or budesonide 2000 mcg daily) (67% vs. 62%; P = 0.37). There continued to be low rates of maintenance steroid therapy (41% vs. 31%; P = 0.29) and assessment of both symptoms and histology to follow treatment response (7% vs. 13%; P = 0.11). There was no change in practice of dilation therapy to manage clinically significant strictures (62% vs. 63%; P = 0.37).

Table 3.

Comparison of concordance between EoE practice patterns and consensus guidelines† among gastroenterologists in North Carolina between 2010 and 2017

| 2010 (n = 38) | 2017 (n = 65) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EoE diagnostic criteria with guideline recommendations highlighted for diagnosis (%) | |||

| Positive biopsy only | 21 | 3 | <0.01 |

| Consistent symptoms only | 0 | 0 | — |

| Consistent symptoms + positive biopsy | 16 | 2 | <0.01 |

| Positive endoscopy findings + positive biopsy | 16 | 14 | 0.39 |

| Consistent symptoms + positive biopsy + one of the following: no clinical or histologic response to PPI and/or negative pH testing | 3 | 14 | 0.03 |

| Consistent symptoms + positive endoscopy findings + positive biopsy + one of the following: no clinical or histologic response to a PPI and/or negative pH testing | 16 | 16 | 0.48 |

| Consistent symptoms + positive endoscopy findings + positive biopsy | 26 | 11 | 0.02 |

| Aspects of EoE management criteria (%) | |||

| Use of dietary therapy as initial treatment for EoE | 3 | 13 | 0.046 |

| Use of topical steroids as first-line pharmacologic therapy | 56 | 39 | 0.04 |

| ‡Use of initial steroid dose: fluticasone (880–1760) or budesonide (2000 mcg) | 62% | 67 | 0.37 |

| Assess both symptoms and histology as markers or treatment response | 13 | 7 | 0.11 |

| Use of maintenance therapy after steroid response | 31 | 41 | 0.29 |

| Dilation of symptomatic strictures despite treatment or critical strictures | 63 | 62 | 0.37 |

†Recommendations according to the 2011/2013 consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of EoE.

‡Out of the proportion of those using steroids as first-line treatment.

EOE, eosinophilic esophagitis; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor.

DISCUSSION

Considerable advances have been made over the past two decades in our understanding of EoE pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. The rapid evolution of clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis and management of EoE reflects the pace of this progress, but this brings real-world challenges to practicing gastroenterologists who must keep up with and implement the new recommendations in clinical practice. As these challenges are not unique to EoE or gastroenterology,24 it is perhaps not unexpected that only a small portion of our sample (24%) were ‘very familiar’ with consensus guidelines, and even fewer (12%) were fully adherent to all EoE diagnostic guidelines. This finding of low adherence to diagnostic guidelines is also consistent with recent, similar studies on EoE practice patterns, though data remain limited. For example, Chang et al.22 found that only 58% of gastroenterologists felt clinical symptoms of esophageal dysfunction were necessary for diagnosis. Additionally, only 63% felt exclusion of a secondary cause of esophageal eosinophilia was required. Regarding biopsy procurement, 62% of gastroenterologists obtained mucosal samples from both the proximal and distal esophagus, as recommended by diagnostic guidelines, which is significantly higher than the 8% reported by Wallach et al.21 in a cohort of pediatric gastroenterologists.

Management practices among our sample of gastroenterologists differed slightly to those of the sample surveyed by Chang et al.22 Both studies were conducted prior to the dissemination of the most recent 2018 guidelines with the major change of PPIs as first-line therapy.1 The sample in the study by Chang et al. was more adherent to treatment guidelines than our sample, with 48% of gastroenterologists using PPIs as initial monotherapy (vs. 61% in our sample). Of those who did not start with a PPI as initial therapy, 55% recommended topical corticosteroids and 26% recommended dietary elimination therapy. A similar proportion of respondents (67%) found esophageal dilation to be safe and effective. Chang et al. also found that only 45% would repeat endoscopy and biopsy to monitor histologic response, whereas we report that only 16% assessed both symptoms and histology for the purposes of treatment response. Overall, a greater proportion of the providers from the Chang et al. study practiced more in concordance with guideline recommendations, but this may represent a group that is more experienced with EoE management as 27% reported treating 20–50 patients annually, which is higher than in our cohort. Alternately, the differences may represent random practice variation. In addition, the survey by Chang et al. used some scenario-based questions to test application of clinical guidelines, which can also explain the differences in results between the two studies. Finally, our study had response data from the NCSG cohort between 2010 and 2017 allowing for temporal comparisons.

Our study also noted differences in practice patterns based on the practice setting (academic vs. community), with a greater proportion of gastroenterologists working in an academic setting adhering to EoE consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of EoE. These differences likely highlight a need for a wider dissemination of practice guidelines through educational outreach programs that is not restricted to highly specialized esophageal centers. While temporally there is a trend of a larger proportion of gastroenterologists practicing per diagnostic guidelines in 2017 compared with 2010, certain aspects of disease management such as assessing both symptoms and histology for treatment response and use of maintenance therapy after initial steroid response was not concordant with guideline recommendation. This again exemplifies areas of knowledge pertaining to EoE management that need to be better highlighted and disseminated. Of particular note is that our respondent population appears to be more experienced with EoE than might be expected (mean of 18 patients seen per month, with a sizable proportion, 20%, with an interest in esophageal diseases). While this is to be expected with this type of survey (the providers most interested in the topic may be more likely to complete the survey), it also suggests that our findings may represent a ‘best case scenario’ and that they could be an overestimate of guidelines dissemination and penetration into general gastroenterology practice.

Our study has multiple strengths and some limitations. One strength is that providers were recruited from a nationwide sample of gastroenterologists practicing in varied practice settings. To our knowledge, this is the largest sample of US gastroenterologists surveyed to date regarding practice patterns of the diagnosis and management of EoE. Another strength is that we administered the same survey to a cohort of gastroenterologists in 2010 (NCSG members) allowing for comparisons over time to assess for changes in practice. We acknowledge, however, that we are unable to determine whether any of the same providers completed the survey at both time points, as identifying information was not obtained. In terms of limitations, we were not able to calculate a response rate as the survey was dispersed through multiple online listservs without an accurate denominator, so nonrespondents remain uncharacterized. We estimate that the response rate was ~25% for the NCSG cohort and likely lower for the ACG group at <5%, and that those who participated probably had an interest or expertise in EoE suggesting that EoE guideline adherence might even be lower than what was found in this study. The cross-sectional design limits us from drawing definitive causal inferences. While all of our respondents were gastroenterologists, there is also known to be significant variation in EoE comanagement with an allergy/immunology specialist,12 and it is unclear how allergists contribute to consensus guideline adherence and to what degree recommendations are followed by allergists, and this would be an interesting future study to conduct. Another limitation is that the study was conducted prior to the most recent updated guidelines in 2018,1 which for the first time included PPI therapy as first-line EoE treatment, rather than as a diagnostic criterion. Interestingly only 37% of the providers in this study reported using a PPI trial for exclusion of PPI-REE prior to the diagnosis of EoE, suggesting that the changes recommended in the most recent 2018 guidelines1 may not impact practice, because most were not ruling out PPI-REE prior to diagnosing EoE anyway.

In conclusion, EoE practice patterns among gastroenterologists continue to be highly variable. Though reasons for variability are unclear, this survey was not intended to capture barriers and facilitators to guideline adherence, although exploring these factors would be valuable in future work. We speculate that several factors, some unique to EoE, may account for practice heterogeneity. It is commonly stated that it takes 17 years for research evidence to be translated to clinical practice.25 From 2007 to 2018, multiple consensus guidelines and society-based guidelines were published,1,15–17,26 likely not allowing sufficient time for diffusion and saturation into clinical practice prior to a new guideline being published. Because EoE is a rapidly evolving field, EoE would benefit from being prioritized as an area needing greater focus in national gastroenterologic societal meetings and continuing medical education courses. Overall, the low adherence rate to consensus guidelines for EoE in this study underscores the challenges of dissemination and implementation of clinical recommendations and highlights areas of disease diagnosis and management that need to be focused upon for continuing education,27 and emphasizes the rapid advances in knowledge and practice of EoE.

Specific author contributions:Guarantor of the article: Evan S. Dellon. Project conception, data collection, data analysis/interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision: Swathi Eluri; Data interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision: Edward G.A. Iglesia; Data collection, data interpretation, critical revision: Michael Massaro; Project conception, data interpretation, critical revision: Anne F. Peery; Project conception, data interpretation, critical revision: Nicholas J. Shaheen; Project conception, supervision, data interpretation, critical revision: Evan S. Dellon. All authors approved the final version.

Grant support: The National Institutes of Health Awards (5T32AI007062 to E.G.A.I., R01 DK101856 to E.S.D., K24DK100548 to N.J.S.); the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award to S.E.

Potential competing interests: None of the authors have potential competing interests related to this study.

References

- 1. Dellon E S, Liacouras C A, Molina-Infante J et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology 2018; 155: 1022–33.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dellon E S, Hirano I. Epidemiology and natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: 319–32.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Navarro P, Arias A, Arias-Gonzalez L, Laserna-Mendieta E J, Ruiz-Ponce M, Lucendo A J. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the growing incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults in population-based studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019; 49: 1116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer K F et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest 2006; 116: 536–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wen T, Stucke E M, Grotjan T M et al. Molecular diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis by gene expression profiling. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 1289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jensen E T, Kuhl J T, Martin L J, Langefeld C D, Dellon E S, Rothenberg M E. Early-life environmental exposures interact with genetic susceptibility variants in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 632–7.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaheen N J, Mukkada V, Eichinger C S, Schofield H, Todorova L, Falk G W. Natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review of epidemiology and disease course. Dis Esophagus 2018; 31(8): doy015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dellon E S, Kim H P, Sperry S L, Rybnicek D A, Woosley J T, Shaheen N J. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 79: 577–85.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Atkins D, Furuta G T, Liacouras C A, Spergel J M. Eosinophilic esophagitis phenotypes: ready for prime time? Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2017; 28: 312–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koutlas N T, Dellon E S. Progression from an inflammatory to a Fibrostenotic phenotype in eosinophilic esophagitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2017; 11: 382–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dellon E S, Cotton C C, Gebhart J H et al. Accuracy of the eosinophilic esophagitis endoscopic reference score in diagnosis and determining response to treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 14: 31–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arias A, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Tenias J M, Lucendo A J. Efficacy of dietary interventions for inducing histologic remission in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2014; 146: 1639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dellon E S, Woosley J T, Arrington A et al. Efficacy of budesonide vs fluticasone for initial treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2019; 157: 65–73.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iglesia E G A, Reed C C, Nicolai E, Dellon E S. Dietary elimination therapy is effective in most adults with eosinophilic esophagitis responsive to proton pump inhibitors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liacouras C A, Furuta G T, Hirano I et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128: 3–20.e6quiz 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Furuta G T, Liacouras C A, Collins M H et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 1342–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dellon E S, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta G T, Liacouras C A, Katzka D A. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 679–92quiz 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lucendo A J, Molina-Infante J, Arias A et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United European Gastroenterol J 2017; 5: 335–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sperry S L, Shaheen N J, Dellon E S. Toward uniformity in the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE): the effect of guidelines on variability of diagnostic criteria for EoE. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 824–32quiz 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peery A F, Shaheen N J, Dellon E S. Practice patterns for the evaluation and treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 32: 1373–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wallach T, Genta R M, Lebwohl B, Green P H R, Reilly N R. Adherence to celiac disease and eosinophilic esophagitis biopsy guidelines is poor in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017; 65: 64–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang J W, Saini S D, Mellinger J L, Chen J W, Zikmund-Fisher B J, Rubenstein J H. Management of eosinophilic esophagitis is often discordant with guidelines and not patient-centered: results of a survey of gastroenterologists. Dis Esophagus 2019; 32(6): doy 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang K Z, Jensen E T, Chen H X et al. Practice pattern variation in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis in the Carolinas EoE collaborative: a research model in community and academic practices. South Med J 2018; 111: 328–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cabana M D, Rand C S, Powe N R et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999; 282: 1458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morris Z S, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med 2011; 104: 510–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Papadopoulou A, Koletzko S, Heuschkel R et al. Management guidelines of eosinophilic esophagitis in childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014; 58: 107–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grimshaw J M, Thomas R E, MacLennan G et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 2004; 8: iii–v1–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]