Abstract

Purpose of Review

We aim to provide quantitative evidence on the psychological impact of epidemic/pandemic outbreaks (i.e., SARS, MERS, COVID-19, ebola, and influenza A) on healthcare workers (HCWs).

Recent Findings

Forty-four studies are included in this review. Between 11 and 73.4% of HCWs, mainly including physicians, nurses, and auxiliary staff, reported post-traumatic stress symptoms during outbreaks, with symptoms lasting after 1–3 years in 10–40%. Depressive symptoms are reported in 27.5–50.7%, insomnia symptoms in 34–36.1%, and severe anxiety symptoms in 45%. General psychiatric symptoms during outbreaks have a range comprised between 17.3 and 75.3%; high levels of stress related to working are reported in 18.1 to 80.1%. Several individual and work-related features can be considered risk or protective factors, such as personality characteristics, the level of exposure to affected patients, and organizational support.

Summary

Empirical evidence underlines the need to address the detrimental effects of epidemic/pandemic outbreaks on HCWs’ mental health. Recommendations should include the assessment and promotion of coping strategies and resilience, special attention to frontline HCWs, provision of adequate protective supplies, and organization of online support services.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Healthcare workers, Mental health, Psychological distress, Pandemic, Epidemic, COVID-19

Introduction

In December 2019, an outbreak of a novel coronavirus pneumonia, namely, coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19), hit Wuhan (Hubei, China). During the following weeks, other significant outbreaks of COVID-19 were reported across the world and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic on 11 March 2020.

In the last 20 years, other outbreaks of novel infectious diseases occurred all over the world. Recent examples are the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and the 2009–2010 A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. Overall, pandemic situations require intense and immediate response in terms of healthcare, with thousands of healthcare workers (HCWs), either directly (e.g., physicians, nurses) or indirectly (e.g., aides, laboratory technicians, and medical waste handlers) delivering care to patients, fighting at the frontline to address the challenges posed to healthcare systems by the almost three million patients infected by the time we are writing.

HCWs are thus facing critical situations that increase their risk of suffering for the psychological impact of dealing with a number of unfavorable conditions, with consequences that might span from psychological distress to mental health symptoms.

Why Is This Review Needed?

HCWs responding to a pandemic outbreak are exposed to physical and psychological stressors that may result in severe mental health outcomes. Furthermore, healthcare workforces play a crucial role in successfully responding to a pandemic situation. In this sense, potential psychological negative consequences not only are detrimental to HCWs’ well-being but might also reduce their ability to address effectively the heath emergency.

The worldwide spread of COVID-19 is challenging the capacity of response of healthcare systems, and policymakers need evidence to address the issue of psychological distress and mental health of HCWs, given their role in responding to the situation. WHO recommends rapid reviews of empirical evidence in these circumstances [1], in order to give recommendations that may help strengthening the response capacity of healthcare systems.

For this reason, we performed a review of empirical studies on the impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare providers in terms of psychological distress and mental health. Our review is aimed at providing evidence on maladaptive psychological outcomes in HCWs facing epidemic/pandemic situations. Moreover, we aim to identify potential risk and protective factors for such maladaptive consequences.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We systematically searched potentially eligible articles on PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases on 30 March 2020. We used the following combinations of terms: “infect*”, “COVID*”, “SARS”, “influenza”, “flu”, “MERS”, “ebola”, “Mental”, “Psych*”, “Health Personnel”, “health worker”, “Medical Staff”, “Physician”, and “Nurses”. The full search strategy is available in Appendix 1. We developed the following set of inclusion criteria for papers to be included in our review:

Studies had to report on primary research

Studies had to be published in a peer-reviewed journal

Studies had to be written in English

Studies had to include data on healthcare providers’ mental health or psychological well-being or data on factors associated with healthcare providers’ mental health or psychological well-being during epidemic/pandemic (i.e., SARS, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV), COVID-19, ebola virus disease (EVD), and influenza A (A/H1N1 and A/H7N9))

Excluding criteria were as follows:

Qualitative studies

Studies focused on distress prevention programs during epidemic/pandemic

Studies focused on emergency situations not related to epidemic/pandemic (i.e., wars, natural disasters, and terroristic attacks)

We removed duplicates through Zotero software version 5.0. In the first stage, four independent researchers (GP, PT, MM, and FF) screened titles and abstracts of the papers we found. In the second stage, the same researchers screened the full texts of all remaining studies to assess their eligibility. In both stages, disagreements were solved through discussion with EP and RC.

Data Extraction

The authors extracted data about the following: publication year, country of study, the type of epidemic/pandemic, participant information (number, occupation), design, assessment scales, time period of study, and main results on psychological outcomes.

To synthesize the data, we performed a qualitative synthesis of findings. We first described psychiatric and psychological difficulties of HCWs during and after epidemics/pandemics; then, we summarized risk and protective factors related to these psychological outcomes.

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

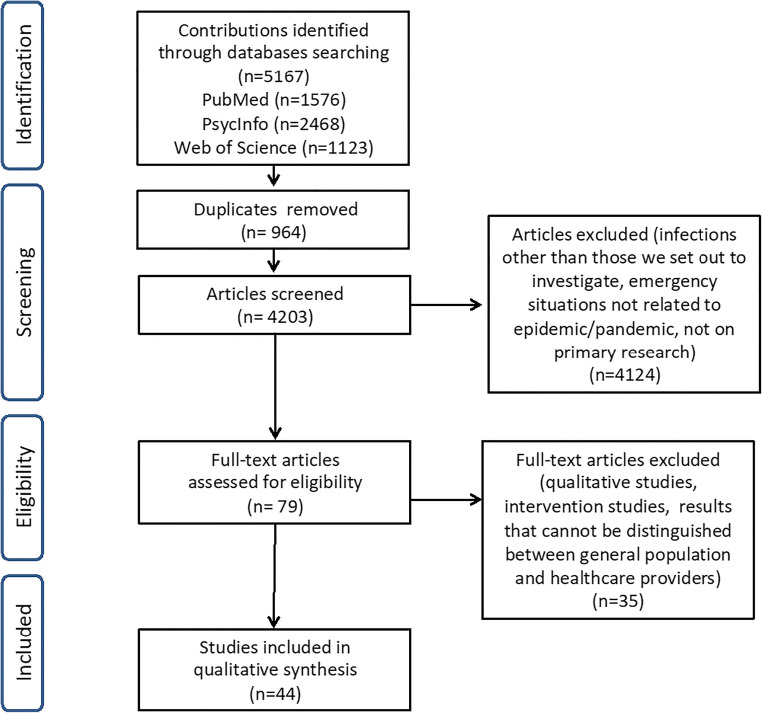

Database search identified 5167 articles; after duplicate removal, 4203 potentially eligible studies remained. After reading titles and abstracts, we excluded 4124 studies; of the remaining 79 studies, 44 met inclusion criteria and were thus included for qualitative synthesis after full-text reading (see Fig. 1 for study selection and Table 1 for a summary of the included studies).

Fig. 1.

Study selection

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Authors, year (country) | Epidemic/pandemic | Participants | Design | Measures | Time of measurement | Main results on psychological outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alsubaie et al., 2019 [2] (Saudi Arabia) | MERS-CoV | 516 HCWs (284 physicians, 164 nurses, and 68 technicians, respiratory therapists) | Cross-sectional | SSM: knowledge and HCWs’ reaction to MERS-CoV; anxiety (5-point Likert) | During the MERS-CoV outbreak | Non-physicians (vs. physicians): ↑ level of anxiety about contracting MERS-CoV and transmitting it to their family members |

| Bai et al., 2004 [3] (Taiwan) | SARS | 338 staff members of psychiatric hospital (218 HCWs, 79 administrative personnel) | Cross-sectional | SSM: SARS-related stress reaction questionnaire | During the SARS outbreak |

- 5% acute stress disorder symptoms - HCWs (vs. non-HCWS): ↑ insomnia, exhaustion, and uncertainty about the frequent modifications to infection control procedures - Quarantine → acute stress disorder |

| Bukhari et al., 2016 [4] (Saudi Arabia) | MERS-CoV | 386 staff members (293 nurses, 34 physicians, 19 healthcare assistants, 12 medical interns, 12 respiratory therapists, 8 radiology technicians, 2 dieticians, 1 faculty member, 1 pharmacist, 1 secretary, 3 other medical staff) | Cross-sectional | SSM: perception of exposure, perceived risk of infection, impact on personal and work life; IES (subscales) | During the MERS-CoV outbreak |

- 56.7% no negative perceptions such as feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge, nor were they unable to stop or control their worrying - Worry about contracting MERS-CoV: 7.8% extremely worried; 20.5% very worried; 34.2% somewhat worried; 27.5% a little worried; 11.9% not worried - Worry about transmitting MERS-CoV to family: 12.2% extremely worried; 21% very worried; 29% somewhat worried; 26.7% a little worried; 11.1% not worried - HR HCWs (vs. non-HR HCWs), female (vs. male): ↑ worries and fear of contracting MERS-CoV |

| Chan et al., 2005 [5] (China) | SARS | 1470 nurses (197 HR: SARS ward or ICUs; 135 MR: SARS ward with some contact with SARS; 1138 LR: no contact with SARS) | Cross-sectional | SSM: SARS nurses’ survey questionnaire | During the peak period of the SARS outbreak |

- 52.6–63.5% good general health - 68.3–80.1% always/often perceived stress from SARS epidemic - Of those who always perceived stress: 50.7% average or poor health (vs. 39% of those who often perceived stress, 28.4% of those who sometimes perceived stress, 18.4% of those who never perceived stress) - MR nurses (vs. HR and LR): ↑ perceived stress; ↓ able to cope with stress |

| Chen et al., 2005 [6] (Taiwan) | SARS | 128 nurses (65 working in HR units, 21 conscripted from LR units into HR units, 42 control LR) | Cross-sectional and case-control | IES; SCL-90-R | During the peak period of the SARS outbreak |

- 11% stress reaction syndrome (IES > 35), with the highest prevalence in the HR units - Conscripted nurses (vs. control and HR): ↑ PTS and psychopathological symptoms - HR nurses (vs. control): ↑ PTS (avoidance) |

| Chen et al., 2007 [7••] (Taiwan) | SARS | 90 HCWs (66 critical care nurses, 11 physicians, 7 technicians, 6 respiratory care specialists) and 82 control subjects (53 administrators, 29 volunteers, assistants, or part-time workers) | Longitudinal and case-control | MOS SF-36 | During the SARS outbreak at 2 time points: immediately after caring for patients with SARS (t0) and 4 weeks after self-quarantine and off-duty shifts (t1) |

- HCWs (vs. control) at t0: ↓ role physical, bodily pain, vitality, role emotional, social functioning, and mental health - HCWs t1 (vs. t0): ↑ social functioning, role emotional and role physical |

| Chong et al., 2004 [8] (Taiwan) | SARS | 1257 staff members (676 nurses, 139 physicians, 140 health administrative workers, 302 other professionals including pharmacists, technicians, and respiratory therapists) | Cross-sectional | SSM: SARS exposure experience; IES; CHQ-12 | 6-week period during SARS outbreak: 727 evaluated in the initial phase and 530 in the repair phase |

- 75.3% psychiatric morbidity (CHQ-12 cut-off = 2/3); initial phase: 71.3%; repair phase: 80.6% - Repair phase (vs. initial phase): ↑ depression, somatic symptoms, avoidance; ↓ anxiety |

| Chua et al., 2004 [9] (China) | SARS | 271 HCWs, 342 healthy control subjects | Cross-sectional and case-control | SSM: a structured list of putative psychological effects of SARS; PSS-10 | During the SARS outbreak | - HCWs (vs. control): ↑ positive psychological effects; LA stress |

| Fiksenbaum et al., 2006 [10] (Canada) | SARS | 333 nurses | Cross-sectional | SSM: perceived SARS threat, performance feedback from other HCWs; SPOS; MBI-GS (emotional exhaustion subscale); STAXI (state anger subscale) | During the SARS outbreak |

- Nurses-P (vs. NP), quarantine, lower organizational support → perceived SARS threat - Perceived SARS threat, lower organizational support: ↑ emotional exhaustion, state anger |

| Goulia et al., 2010 [11] (Greece) | A/H1N1 influenza | 469 HCWs (209 nurses, 120 physicians, 59 allied, 81 auxiliary) | Cross-sectional | SSM: concerns and worries about the new pandemic; GHQ-28 | During the A/H1N1 second outbreak |

- 56.7% worry about the pandemic - 20.7% moderate psychological distress (GHQ-28 > 5); 6.8% severe psychological distress (GHQ-28 > 11) - Worry about the pandemic → psychological distress |

| Grace et al., 2005 [12] (Canada) | SARS | 193 physicians | Cross-sectional | SSM: SARS-related attitudes and perception, coping, concerns, effects on personal relationships, changes to work | During the SARS second outbreak |

- 18.1% perceived stress related to working during the SARS outbreak - Physicians-P (vs. NP): ↑ perceived stress |

| Ho et al., 2005 [13] (China) | SARS |

- Sample 1: 82 SARS HCWs (26 doctors, 21 nurses, 35 auxiliary staff including anesthetists, medical social workers, and physiotherapists) - Sample 2: 97 HCW SARS survivors (4 doctors, 51 nurses, 8 allied health professionals, 34 support staff) |

Cross-sectional |

- Sample 1 - SSM: SARS Fear Scale and Self-Efficacy Scale - Sample 2 - SSM: SARS Fear Scale; CGSE; CIES-R |

- Sample 1: at the peak of the SARS outbreak - Sample 2: 3 months after the peak |

- Sample 1 (vs. sample 2): ↑ fear of infection; ↓ fear of health problems and discrimination - Low self-efficacy: ↑ SARS-related fear - In sample 2: SARS-related fear → PTS symptoms |

| Ji et al., 2017 [14] (Sierra Leone) | EVD | 143 HCWs (59 SL medical staff, 21 SL logistic staff, 22 SL medical students, 41 Chinese medical staff), 18 survivors | Cross-sectional | SCL-90-R | During EVD outbreak; only for Chinese medical staff: at arrival in SL and before departure (5-week period) |

- Psychopathology from high to low (range 0–4): EVD survivors (2.31 ± 0.57), SL medical staff (1.92 ± 0.62), SL logistic staff (1.88 ± 0.68), SL medical students (1.68 ± 0.73), Chinese medical staff (1.25 ± 0.23) - Chinese medical staff at arrival (vs. at departure): LA psychopathology |

| Lai et al., 2020 [15••] (China) | COVID-19 | 1257 HCWs (493 physicians, 764 nurses, among which 522 HCWs-P, 735 HCWs-NP, 760 HCWs working in Wuhan, 261 in Hubei province, 236 outside Hubei province) | Cross-sectional | PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI, IES-R | During COVID-19 outbreak |

- 50.4% depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 5) - 44.6% anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 ≥ 5) - 34% insomnia symptoms (ISI ≥ 8) - 71.5% PTS symptoms (IES-R ≥ 9) - Nurses (vs. physicians), female (vs. male), HCWs-P (vs. NP), HCWs working in Wuhan (vs. outside Hubei) and in secondary hospital (vs. tertiary): ↑ psychopathological symptoms |

| Lancee et al., 2008 [16] (Canada) | SARS | 139 HCWs (103 nurses, 15 clerical staff, 21 various hospital staff) | Cross-sectional | SSM: perception of the SARS-related adequacy of training, protection, and support; CAPS; SCID-I (excl. psychosis and PTSD) | 1 to 2 years after the Toronto SARS outbreak |

- Lifetime prevalence of at least one psychiatric disorder: 30% - Incidence of new episodes of a psychiatric disorder after SARS: 5% - History of psychiatric disorders, less years of experience → new episodes of psychiatric disorders - Perceived adequacy of training and support by the hospital: ↓ new episodes of psychiatric disorders |

| Lee et al., 2007 [17] (China) | SARS | 96 survivors: 63 non-HCWs, 33 HCWs | Cross-sectional and case-control | PSS-10; DASS21; IES-R; GHQ-12 | 1 year after the SARS outbreak | - HCWs (vs. non-HCWs): ↑ stress, anxiety, depressive, and PTS symptoms; ↑ psychiatric morbidity rate (GHQ-12 ≥ 3: 90% vs. 49%) |

| Lee et al., 2018 [18] (South Korea) | MERS | 359 hospital workers (5% doctor, 29.4% technician, 34.6% nurse, 21.7% pharmacist, 17% administrative, 17% others) | Cross-sectional | IES-R |

- First survey: during hospital shutdown for MERS outbreak - Second survey: for those who scored > 25 on the IES-R, 1 month after shutdown was cleared |

- First survey: 64.1% PTS symptoms (IES-R > 18); 51.5% PTSD (IES-R > 25) - Second survey (n = 77): 54.5% PTS symptoms; 40.3% PTSD - MERS-related tasks (vs. unrelated task) at first survey: ↑ PTS |

| Li et al., 2015 [19] (Liberia) | EVD | 52 Liberian HCWs (16 nurses, 36 hygienists) | Cross-sectional | SCL-90-R | During EVD outbreak in Liberia | - Male (vs. female), cleaning and disinfection HCWs (vs. treatment and observation ward HCWs): ↑ psychopathological symptoms |

| Li et al., 2020 [20] (China) | COVID-19 | 526 nurses (234 frontline and 292 non-frontline) and 214 general public | Cross-sectional | SSM: vicarious traumatization | During COVID-19 outbreak |

- Frontline nurses (vs. non-frontline and general public): ↓ vicarious traumatization - Non-frontline (vs. general public): LA vicarious traumatization |

| Liang et al., 2020 [21] (China) | COVID-19 | 59 HCWs (23 doctors, 36 nurses) | Cross-sectional | SDS, SAS | During COVID-19 outbreak | - HR HCWs (vs. LR): LA anxiety and depressive symptoms |

| Lin et al., 2007 [22] (Taiwan) | SARS |

92 HCWS: - 66 doctors and nurses of the ED (HR) - 26 doctors and nurses of the psychiatric ward (MR) |

Cross-sectional | SSM: SARS severity of stress; DTS-C; CHQ-12 | During the month after the end of the SARS outbreak |

- 93.5% considered SARS “stressful” - 19.3% PTSD symptoms (DTS-C > 40) - 47.78% minor psychiatric morbidity (CHQ-12 ≥ 3) - HR HCWs (vs. MR): ↑ PTSD symptoms; LA minor psychiatric morbidity |

| Liu et al., 2012 [23] (China) | SARS | 549 hospital employees | Cross-sectional | SSM: exposure to SARS, exposure to traumatic events, during-outbreak SARS-related risks perception, current high-stress job; CES-D; IES-R | 3 years after SARS outbreak |

- 8.8% high depressive symptom level (CES-D > 24) - Younger age, being single, exposure to other traumatic events, during-outbreak quarantine, perceived SARS-related risk: ↑ depressive symptoms - During-outbreak altruistic acceptance of risk: ↓ depressive symptoms |

| Liu et al., 2020 [24] (China) | COVID-19 | 1563 HCWs | Cross-sectional | PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI, IES-R | During the COVID-19 outbreak |

- 50.7% depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 5) - 44.7% anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 ≥ 8) - 36.1% insomnia symptoms (ISI ≥ 8) - 73.4% PTS symptoms (IES-R ≥ 9) |

| Lu et al., 2006 [25] (Taiwan) | SARS | 127 HCWs who had worked with suspected SARS patients (24 physicians, 49 nurses, 54 technicians/attendants) | Cross-sectional | PBI; EPQ; CHQ-12 | During the SARS outbreak but after its main outbreak |

- 17.3% psychiatric morbidity (CHQ-12 ≥ 3) - Dysfunctional maternal attachment, neuroticism: ↑ psychiatric morbidity |

| Lung et al., 2009 [26] (Taiwan) | SARS | 123 HCWs who had worked with suspected SARS patients (22 physicians, 48 nurses, 53 technicians/attendants) | Longitudinal |

Study 1 (Lu et al., 2006): PBI; EPQ; CHQ-12 Study 2 (Lung et al., 2009): CHQ-12 SSM: daily life stressful events in the past year |

1 year after the SARS outbreak |

- 15.4% psychiatric morbidity (CHQ-12 ≥ 3) - Psychiatric morbidity at t0 → psychiatric morbidity at t1 - Daily life stressful events in the year following the outbreak, neuroticism: ↑ psychiatric morbidity at t1 |

| Marjanovic et al., 2007 [27] (Canada) | SARS | 333 nurses | Cross-sectional | SSM: avoidance behavior scale, vigor scale, trust in equipment/infection control, contact with SARS patients, time spent in quarantine; MBI-GS (emotional exhaustion subscale); STAXI; adaptation of SPOS | During the SARS outbreak |

- Vigor, organizational support, trust in equipment/infection control: ↓ avoidance behavior, emotional exhaustion, state anger - Quarantine: ↑ avoidance behavior, state anger - Nurses-P (vs. NP): ↑ emotional exhaustion |

| Matsuishi et al., 2012 [28] (Japan) | A/H1N1 influenza | 1625 hospital staff (218 physicians, 864 nurses, 543 other employees) | Cross-sectional | SSM: stress-related questions; IES-R | 1 month after the peak of the H1N1 outbreak |

- HR area (vs. LR): ↑ PTS, infection anxiety, exhaustion - Physicians (vs. other): ↓ PTS, infection anxiety - Nurses (vs. other): ↑ exhaustion |

| Maunder et al., 2004 [29] (Canada) | SARS | 1557 hospital staff (430 nurses, 117 clerical, 117 research laboratory, 115 physician, 112 administration, 106 clinical laboratory, 48 social work, 45 occupational therapy/physiotherapy, 43 pharmacy, 27 clinical assistant, 26 housekeeping, 32 other clinical jobs, 80 other nonclinical jobs, 259 other jobs) | Cross-sectional | SSM: 76 items probing attitudes toward SARS; IES | During the SARS outbreak |

- Nurses (vs. other), HCWs-P (vs. NP): ↑ PTS - Fear for one’s health and the health of others, social isolation and avoidance, and job-related stress fully mediated the traumatic response to SARS |

| Maunder et al., 2006 [30] (Canada) | SARS |

587 HR HCWs, 182 LR HCWs Survey A: 769 (73.5% nurses, 8.3% clerical staff, 2.9% physicians, 2.3% respiratory therapists, 12.9% other job types) Both survey A and B: 187 |

Cross-sectional and case-control |

Survey A: SSM: changes in work (hours and face-to-face contact), increase in smoking, drinking alcohol, or “other activities that could interfere with work or relationships,” number of missed work shifts; IES; K10; MBI-EE Survey B: SSM: perception of stigma and interpersonal avoidance, adequacy of training, protection, and support, job stress; WCQ (subscales); ECR-R (anxiety and attachment avoidance scales) |

13–26 months after the SARS outbreak |

- HR HCWs (vs. LR): ↑ burnout, psychological distress, PTS, substance use, other maladaptive behaviors and days off work; ↓ patient contact and work hours - Maladaptive coping → burnout, psychological distress, PTS - Training, support, and protection: ↓ burnout, PTS |

| McAlonan et al., 2007 [31••] (China) | SARS |

T0: 106 HR HCWs (who worked in SARS isolation units), 70 LR HCWs (who worked in psychiatric inpatient units) T1: 71 HR HCWs, 113 LR HCWs |

Longitudinal and case-control |

T0: PSS-10 T1: PSS-10; DASS-21; IES-R |

At the peak of the SARS outbreak (t0) and 1 year later (t1) |

- HR HCWs (vs. LR) at t0: ↑ fatigue, poor sleep, worry about health, fear of social contact - HR HCWs (vs. LR) at t1: ↑ stress, depression, anxiety - Time (t0 vs. t1) × risk (HR vs. LR): decrease in stress for LR HCWs and increase in stress for HR HCWs |

| Mohammed et al., 2015 [32] (Nigeria) | EVD | 117 survivors of EVD, contacts or relatives of a known case of EVD (45 HCWs, 38.5%) | Cross-sectional | GHQ-12; OSS | During the EVD outbreak | - HCWs (vs. non-HCWs): ↓ psychological morbidity (feeling unhappy or depressed) |

| Nickell et al., 2004 [33] (Canada) | SARS | 1983 hospital staff (173 physicians, 476 nurses, 615 allied HCWs, 593 workers not involved in patient care). Only 510 workers received the GHQ-12 | Cross-sectional | SSM: concerns about SARS, use and effects of SARS precautionary measures; GHQ-12 | During the peak of the initial phase of the SARS outbreak |

- 29% minor psychiatric morbidity (GHQ-12 > 3) - 62.7–64.7% SARS-related concern for personal-family health - Stigma, perceived risk of death, lifestyle affected by SARS, reduced trust in precautionary measures → concern for personal or family health - Nurses, part-time job, lifestyle affected by SARS, job ability affected by precautionary measure → psychological morbidity |

| Park et al., 2018 [34] (South Korea) | MERS-CoV | 187 nurses working in HR areas for the MERS-CoV | Cross-sectional | SSM: MERS-CoV stigma scale; MOS SF-36; PSS-10; DRS-15 | During the MERS-CoV outbreak |

- Hardiness: ↑ mental health (both directly and indirectly via perceived stress) - Stigma: ↓ mental health (both directly and indirectly via perceived stress) |

| Phua et al., 2005 [35] (Singapore) | SARS | 96 ED HCWs (38 physicians and 58 nurses) who cared for SARS patients | Cross-sectional | COPE; GHQ-28; IES | 6 months after the end of the SARS outbreak |

- 17.7% PTS symptoms (IES ≥ 26) - 18.8% psychiatric morbidity (GHQ-28 ≥ 5) - Less functional coping strategies → psychiatric morbidity |

| Son et al., 2019 [36] (China) | MERS | 280 hospital workers (153 HCWs, 127 non-HCWs) | Cross-sectional and case-control | IES-R; CD-RISC; SSM (5-point Likert scale): willingness to work; SSM (5-point Likert scale): perceived risk of the disease; SSM (9-point Likert scale): negative emotional experience | 1 month after the end of the MERS outbreak announced by the public health authority |

- 18.6% PTSD (IES-R ≥ 22) - HCWs (vs. non-HCWs): ↑ PTSD and negative emotional experience - Perceived risk, negative emotional experience: ↑ PTSD |

| Styra et al., 2008 [37] (Canada) | SARS | 248 HCWs: 160 from HR units (120 ICU, 24 SARS units, 16 ED); 88 from LR units | Cross-sectional and case-control | SSM: personal risk perception, perception of risk to others, confidence in infection control measures, confidence in information about SARS, impact on personal life, impact on work life, depressive affect; IES-R | 3–4 months after SARS outbreak in Toronto | - Risk perception, depressive affect, SARS impact on work life, HR units (vs. LR), caring for only one SARS patient → PTS symptoms |

| Su et al., 2007 [38] (China) | SARS | 102 nurses: 70 from SARS units (44 regular units; 26 SARS ICU), 32 from non-SARS units (17 from CCU; 15 from NU) | Longitudinal (1-month study) |

Weekly: SSM only for SARS unit nurses: attitude scale toward SARS (knowledge and understanding, perceived negative feelings, positive attitudes toward patients); BDI; STAI; DSM-IV insomnia; PSQI Biweekly: DTS-C At baseline and at the end of the study (only for SARS unit nurses): SDS; modified family APGAR index 1 month after the end of the study: MINI |

During SARS outbreak |

- SARS unit nurses (vs. non-SARS): ↑ symptomatic depression (38.5% vs. 6.7%), insomnia (37.1% vs. 9.4%); LA PTSD - Time effect: ↓ depression, PTSD, sleep disturbance, impairment in life, perceived negative feelings of SARS; ↑ positive attitudes toward SARS patients - Time × group effect: decrease in anxiety and sleep disturbance in SARS units (vs. non-SARS units) |

| Tam et al., 2004 [39] (China) | SARS | 652 frontline HCWs (62% nurses; 24% HC assistants; 3% medical professionals) | Cross-sectional | SSM: subjective job-related stress before, during, and after the outbreak, coping behaviors, adequacy of various support items, positive and negative perspectives of the outbreak; GHQ-12 | Near the end of SARS outbreak |

- 68% significant/severe job-related stress - 56.7% psychiatric morbidity (GHQ-12 ≥ 3) - Nurse (vs. other), female (vs. male), poor self-rated physical health (vs. fair/good), unwillingness to work in SARS units, job-related stress, inadequate support in the workplace → psychiatric morbidity |

| Tang et al., 2017 [40] (China) | A/H7N9 influenza | 102 HCW exposed to H7N9 patients (26 doctors, 62 nurses, 14 interns) from 3 units: respiratory department (N = 20), ED (N = 21), ICU (N = 61) | Cross-sectional | PCL-C | From 2 to 3 years after the beginning of H7N9 outbreak |

- 20.59% PTS symptoms (PCL-C ≥ 38) - Nurse (vs. doctor), female (vs. male), younger age (21–30 years vs. > 30 years), intermediate and subsenior titles (vs. primary), work experience < 5 years (vs. > 5 years), HCWs-P (vs. NP), no training (vs. training): ↑ PTS symptoms |

| Tham et al., 2005 [41] (China) | SARS | 96 ED HCWs (38 doctors; 58 nurses) | Cross-sectional | IES-R; GHQ 28 | 6 months after SARS outbreak |

- 17.7% PTS symptoms (IES-R ≥ 26) (doctors: 13.2%; nurses: 20.7%) - 18.8% psychiatric morbidity (GHQ-28 ≥ 5) (doctors 15.8%; nurses 20.7%) |

| Wong et al., 2005 [42] (China) | SARS | 466 ED HCWs (123 doctors, 257 nurses, 82 HCAs) from different public hospitals | Cross-sectional |

- SSM (single-item, 10-point Likert scale): level of perceived stress at the time of the survey - SSM (4-point Likert scale): 6 sources of stress (health of self, health of family/others, virus spread, vulnerability/loss of control, changes in work, being isolated) - Brief COPE |

Immediately after the end of SARS outbreak |

- Perceived stress: highest score for nurses (M = 6.52), followed by doctors (M = 5.91) and HCA (M = 5.44) - Nurses (vs. HCAs): ↑ perceived stress - HCAs (vs. doctors): ↑ worries about health of family/others |

| Wong et al., 2010 [43] (China) | A/H1N1 influenza | 267 community nurses | Cross-sectional | SSM: clinical services, internal environment and macroenvironmental changes as a response H1N1 influenza; professional and public health responsibilities with respect to H1N1 influenza; willingness to continue to work during H1N1 influenza | During H1N1 influenza outbreak |

- 33.3% “not willing” and 43.6% “not sure” about caring for H1N1 patients - Perceived stress, infection-related worries, dissatisfaction about hospital management → unwillingness to work |

|

Wu et al., 2009 [44] (China) |

SARS | 549 hospital employees (20.7% doctors; 37.6% nurses; 22.1% technicians; 19.6% administrative + other hospital staff) | Cross-sectional | SSM: SARS outbreak exposures (work exposure, quarantining, relative or friend got SARS), media exposure, other potentially traumatic events pre-SARS and post-SARS exposure, during-outbreak risk perception; altruistic acceptance of the risk, current fear of future SARS outbreaks; modified IES-R | 3 years after SARS outbreak |

- 10% PTS symptoms (IES-R ≥ 20) during the 3 years after SARS (HR units: 46.9%) - SARS exposure (work exposure, quarantining, relative or friend got SARS), during-outbreak perceived risk: ↑ PTS symptoms since SARS - Risk perception partially mediated the relationship SARS exposure-PTS symptoms - Altruistic acceptance of risk: ↓ PTS symptoms since SARS, current fear of SARS |

| Xiao et al., 2020 [45•] (China) | COVID-19 | 180 medical staff members (82 doctors, 98 nurses) | Cross-sectional | SSRS; SAS; GSES; SASR; PSQI | 1–2 months after the beginning of COVID-19 outbreak |

- Low sleep quality (PSQI = 8.58 ± 4.567) in the sample - Social support: ↓ anxiety, stress; ↑ self-efficacy - Social support: no direct effect on sleep quality > anxiety, stress, self-efficacy mediated the relationship social support- sleep quality |

Of importance

Of major importance

MERS-CoV Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection, HCWs healthcare workers, SSM study-specific measure, SARS severe acute respiratory syndrome, IES Impact of Event Scale, HR high-risk, ICUs intensive care units, MR moderate-risk, LR low-risk, SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, PTS post-traumatic stress, MOS SF-36 Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36, CHQ-12 Chinese Health Questionnaire-12, PSS-10 Perceived Stress Scale-10, LA lack of association, SPOS Survey of Perceived Organizational Support, MBI-GS Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey, STAXI State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory, P contact with affected patients, NP no contact with affected patients, GHQ-28 General Health Questionnaire-28, CGSE Chinese General Self-Efficacy Scale, CIES-R Chinese version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised, EVD ebola virus disease, SL Sierra Leone, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, ISI Insomnia Severity Index, IES-R Impact of Event Scale-Revised, CAPS Clinician Administered PTSD Scale, SCID-I Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder, DASS-21 Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, SDS Self-Rating Depression Scale, GHQ-12 General Health Questionnaire-12, SAS Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, ED emergency department, DTS-C Davidson Trauma Scale-Chinese version, CES-D Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, PBI Parental Bonding Instrument, EPQ Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, K10 Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, MBI-EE Maslach Burnout Inventory-Emotional Exhaustion scale, WCQ Ways of Coping Questionnaire, ECR-R Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised questionnaire, OSS Oslo Social Support scale, DRS-15 Dispositional Resilience Scale-15, COPE Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced, CD-RISC Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, CCU coronary care unit, NU neurology unit, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, STAI State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, DSM-IV Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, MINI Mini International diagnosis for Neuropsychiatric Interview, PCL-C PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version, HCAs healthcare assistants, SSRS Social Support Rate Scale, GSES General Self-Efficacy Scale, SASR Stanford Acute Stress Reaction

Among the included studies, 27 (62%) referred to the SARS outbreak, 5 (11%) to the MERS-CoV outbreak, 5 (11%) to the COVID-19 outbreak, 3 (7%) to the A/H1N1 influenza outbreak, 3 (7%) to the EVD outbreak, and 1 (2%) to the A/H7N9 influenza outbreak.

The studies were conducted in different countries: China (19 studies), Canada (eight studies), Taiwan (seven studies), South Korea (two studies), Saudi Arabia (two studies), Greece (one study), Nigeria (one study), Sierra Leone (one study), Liberia (one study), Singapore (one study), and Japan (one study).

Thirty-four studies (77%) considered only HCWs, namely, physicians, nurses, and auxiliaries, whereas both HCWs and other staff members such as administrative workers and technicians were included in ten studies (23%).

All the studies investigated psychological outcomes by means of both validated questionnaires and interviews and/or study-specific measures.

Psychopathological Symptoms

Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms

Post-traumatic stress reactions were examined in 23 studies [3, 6, 8, 13, 15••, 16–18, 22–24, 28–30, 31••, 35–38, 40, 41, 44]. See Table 2 for a detailed description of psychological outcomes included in each study and their findings.

Table 2.

Description of study results classified by psychological outcomes

| Psychological outcomes | Studies | Measures | Prevalence rates | Associations with other psychological outcomes | Case-control studies | Longitudinal studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTS symptoms | 22 studies [3, 6, 8*, 13*, 15••, 16*, 17*, 18, 22, 23*, 24, 28, 29*, 30, 31••*, 35, 36*, 37, 38, 40, 41, 44] | CAPS, CIES-R, DTS-C, IES, IES-R, PCL-C |

- During the outbreak [6, 15••, 18, 24]: 11–73.4% - 1 month after the end of the outbreak [22, 36, 38]: 18.6–28.4% - 6 months after the end of the outbreak [35, 41]: 17.7% - From 1 to 3 years after the end of the outbreak [30, 40, 44]: 10–20.59% |

Positive association: depressive symptoms [23], current fear of SARS [44] | - Significant higher PTS symptom level in HCWs compared with non-HCWs [38, 36] | - After 1 month: significant reduction in PTS symptom level [20] |

| Vicarious traumatization | 1 study [20*] | SSM | - Significantly lower levels of vicarious traumatization in frontline nurses than the control group; no significant difference between non-frontline nurses and controls [46] | |||

| Depressive symptoms | 7 studies [15••, 17*, 21, 23, 24*, 31••, 38*] | BDI, CES-D, DASS-21, PHQ-9, SDS, SSM |

- During the outbreak [15••, 24, 38]: 27.5–50.7% - 3 years after the end of the outbreak [23]: 8.8–14% |

Positive association: PTS symptoms [37] | - Significantly higher depressive symptom level in HCW SARS survivors compared with non-HCW survivors [17] | - After 1 month: significant reduction in depression level [38] |

| Insomnia symptoms | 5 studies [3*, 15••, 24, 38, 45•*] | DSM-IV insomnia criteria, ISI, PSQI, SSM | - During the outbreak [15••, 24, 38]: 28.4–36.1% | - Significantly higher insomnia in HCWs compared with non-HCWs [3] | - After 1 month: significant improvement in sleep quality [38] | |

| Anxiety symptoms | 7 studies [15••, 17, 21, 24*, 31••*, 38, 45•*] | DASS-21, GAD-7, STAI, SAS |

- During the outbreak [15••, 24]: 44.6–44.7% - 1 year after the end of the outbreak [17]: 14–36.7% |

Positive association: distress [45•] Negative association: sleep quality, self-efficacy [45•] |

- Significantly higher anxiety level in HCW SARS survivors compared with non-HCW survivors [17] | - After 1 month: significant reduction in anxiety scores [38] |

| Psychiatric morbidity/general psychological distress | 18 studies [6*, 7••, 8, 11, 14, 16, 17, 19, 22, 25, 26*, 30*, 32, 33, 34*, 35*, 39*, 41] | CHQ-12, GHQ-12, GHQ-28, K10, SF-36, SCID-I, SCL-90-R |

- During the outbreak [8, 11, 25, 33, 39]: 17.3–75.3% - 1 month after the end of the outbreak [22]: 47.7% - 6 months after the end of the outbreak [35, 41]: 18.8% - 1 year after the outbreak [26]: 15.4% |

- Significant higher levels of psychiatric morbidity in HCW SARS survivors compared with non-HCW survivors [17] - Significant lower scores in role physical, bodily pain, vitality, role emotional, social functioning, and mental health subscales in HCWs compared with controls [7••] - Significant lower GHQ-12 scores in HCW EVD survivors compared with non-HCW survivors [32] |

- Differences between CHQ first-stage and second-stage scores were not evaluated; first-stage CHQ symptoms had a positive direct effect on the second-stage results [26] - After 1 month: significant improvement in social functioning, role emotional, and role physical scores [7••] |

|

| Perceived stress | 12 studies [5*, 9*, 12*, 17, 22*, 28*, 31••, 34, 39*, 42, 43, 45• ] | PSS-10, SASR, SSM |

- During the outbreak [5, 12, 39]: 18.1–80.1% - 1 month after the end of the outbreak [22]: 4.3–47.8% |

Positive association: depression [31••], anxiety [31••, 38], PTS symptoms [22] Negative association: general health [5], sleep quality [38, 45•], willingness to work [43] |

- Significantly higher stress levels in HCWs compared with non-HCWs [17] - Non-significant differences in stress levels between HCWs and controls [9] |

- After 1 year: significant decrease in stress for LR-HCWs; significant increase in stress for HR-HCWs [31••] |

| Infection-related worries | 5 studies [2, 4, 11*, 12*, 33] | SSM |

- During the outbreak [4, 33]: 7.5–64.7% - 1 month after the end of the outbreak [11]: 56.7% |

Negative association: willingness to work [43] | ||

| Burnout | 3 studies [10, 27*, 30*] | MBI-GS, SSM | - From 1 to 2 years after the end of the outbreak [30]: 30.4% | - Significantly higher exhaustion level in HCWs compared with non-HCWs [3] |

*No reported prevalence rates

Of importance

Of major importance

PTS post-traumatic stress, CAPS Clinician Administered PTSD Scale, CIES-R Chinese version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised, IES Impact of Event Scale, IES-R Impact of Event Scale-Revised, DTS-C Davidson Trauma Scale-Chinese version, PCL-C PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version, SARS severe acute respiratory syndrome, HCWs healthcare workers, SSM study-specific measure, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, CES-D Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, DASS-21 Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9, SDS Self-Rating Depression Scale, DSM-IV Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV, ISI Insomnia Severity Index, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, STAI State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, SAS Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, CHQ-12 Chinese Health Questionnaire-12, GHQ-12 General Health Questionnaire-12, GHQ-28 General Health Questionnaire-28, K10 Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, SF-36 Short-form 36, SCID-I Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, EVD ebola virus disease, PSS-10 Perceived Stress Scale-10, SASR Stanford Acute Stress Reaction, LR-HCWs low-risk healthcare workers, HR-HCWs high-risk healthcare workers, MBI-GS Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey

During outbreaks, the prevalence of PTSD-like symptoms was comprised between 11 and 73.4%. Moreover, 51.5% of HCWs scored above the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) threshold for a PTSD diagnosis [6, 15••, 18, 24]. Studies on the COVID-19 pandemic [15••, 24] reported the highest prevalence rate (71.5–73%). In contrast, only 5% of the staff members of a psychiatric hospital met the DSM-IV criteria for an acute stress disorder during the SARS outbreak [3]. However, the authors underlined that the specific type of institution they considered limits the generalizability of this result [3].

Other studies examined PTSD manifestations after the end of the outbreaks. Findings suggest that from 18.6 to 28.4% of HCWs still have significant PTSD symptoms after 1 month from the end of the pandemic [22, 36, 38], 17.7% after 6 months [35, 41], and 10–40% after 1–3 years [30, 40, 44].

Two case-control studies observed that HCWs showed a significant higher post-event morbidity to outbreak exposure, compared with non-HCWs [17, 36].

Depression and Anxiety Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were examined in seven studies [15••, 17, 21, 23, 24, 31••, 38]. During the acute phase of pandemic, the prevalence of depressive symptomatology was between 27.5 and 50.7% in HCWs [15••, 24, 38], with higher rates during the COVID-19 pandemic (50.4–50.7%), compared with SARS outbreak (27.6%). Three years after the end of the Beijing SARS epidemic, about 14% of the interviewed hospital staff members still showed moderate depressive symptoms, and 8.8% reported high symptom levels [23].

Five studies specifically investigated insomnia and sleep quality [3, 15••, 24, 38, 45•]. The DSM-IV criteria for insomnia were met in 28.4% of nurses, with the highest insomnia rate for the regular SARS unit (50%), followed by the SARS intensive care unit (23%), whereas no cases were found in non-SARS units [38]. Significant self-reported insomnia symptoms were observed in 34–36.1% of COVID-19 HCWs [15••, 24]. Moreover, low sleep quality was reported by medical staff members treating COVID-19 patients [45•].

Five studies investigated anxiety symptoms through standardized self-reported questionnaires during outbreaks [15••, 21, 24, 38, 45•], and two studies examined anxiety symptoms 1 year after pandemic resolution [17, 31••]. Two extensive studies conducted during the peak phase of COVID-19 pandemic reported that about 45% of HCWs presented severe anxiety symptoms [15••, 24]. Among medical staff members treating COVID-19 patients, anxiety levels affected psychological well-being, by increasing levels of distress and decreasing sleep quality and self-efficacy [45•].

One study prospectively evaluated changes in anxiety symptoms in a sample of SARS nurses over time [38]. Findings suggest a significant reduction in both depressive and anxiety symptoms at 1-month follow-up, as well as significant improvement in sleep quality.

In a case-control study, Lee and colleagues [17] found significantly higher depressive and anxiety symptom levels among HCW survivors compared with non-HCW survivors 1 year after the end of the SARS epidemic.

Psychiatric Morbidity and General Psychological Distress

Eighteen studies investigated HCWs’ mental health using screening measures of psychiatric symptoms and psychological distress and questionnaires of general health status [6–8, 11, 14, 16, 17, 19, 22, 25, 26, 30, 32–35, 39, 41].

Specifically, five studies investigated psychiatric symptoms during outbreaks through the General Health Questionnaire, reporting a considerable variability in prevalence rates, with a range comprised between 17.3 and 75.3% [8, 11, 25, 33, 39].

One month after the end of the SARS outbreak, 47.8% of hospital staff members showed psychiatric symptoms [22]. Six months after the SARS epidemic, 18.8% of HCWs presented psychiatric symptoms [35, 41].

Between 1 and 2 years after SARS resolution, the incidence of new episodes of psychiatric disorders (diagnosed with the SCID-I, excluding the psychotic disorders and PTSD) was of 5% in HCWs in Toronto [16]. Similarly, 1 year after the end of the SARS epidemic, 15.4% of the respondents still showed significant mental health symptoms [26].

One year after the end of the SARS outbreak, HCW survivors had a sixfold increased risk for psychiatric symptoms, compared with non-HCW survivors, even after controlling for age, sex, and education level [17]. Conversely, in a study on EVD survivors, Mohammed and colleagues [32] found that being a HCW was a protective factor for depressive feelings.

Psychological Impact

Perceived Stress

Twelve studies investigated HCWs’ perceived stress during outbreaks [5, 9, 12, 17, 22, 28, 31••, 34, 39, 42, 43, 45•]. From 18.1 to 80.1% of HCWs reported high levels of work-related stress during the SARS outbreak [5, 12, 39].

Moreover, HCW survivors reported higher perceived stress than survivors from the general population 1 year after the end of the SARS outbreak [17]. Conversely, Chua and colleagues [9] found no significant differences in perceived stress between HCWs and healthy control subjects after the SARS outbreak.

One prospective study [31••] examined changes in perceived stress among high-risk and low-risk HCWs over time, from the peak of the SARS outbreak to 1 year after resolution. The authors observed a significant time × risk interaction effect, with a general trend toward a decrease of perceived stress for low-risk HCWs and an increase of perceived stress for high-risk HCWs.

Infection-Related Worries

Five studies specifically investigated HCWs’ infection-related worries through non-standardized ad hoc measures [2, 4, 11, 12, 33].

Nickell and colleagues [33], in a study on a large sample of hospital staff members, found that 64.7% of the respondents expressed SARS-related concerns for personal health and 62.7% for family health during the peak phase of the outbreak. Bukhari and colleagues [4] examined fears related to contracting and transmitting MERS-CoV in a sample of Saudi Arabian HCWs working during the outbreak. The authors found that from 7.8 to 20.5% of the respondents were extremely very worried about contracting MERS-CoV over the past 4 weeks; from 12.2 to 21% of the sample reported to be extremely very worried about transmitting the infection to family members or friends. One month after the end of the A/H1N1 pandemic, Goulia and colleagues [11] found that 56.7% of their sample still expressed a moderately high level of concern about the disease.

Burnout

Three studies investigated HCWs’ burnout reactions to outbreaks, specifically examining its emotional exhaustion component [10, 27, 30]. One to 2 years after the SARS outbreak, 30.4% of HCWs who had direct contact with infected patients still reported a high level of emotional exhaustion [30].

Bai and colleagues [3] found a significantly higher level of emotional exhaustion among SARS HCWs compared with non-HCWs. However, the authors measured emotional exhaustion through a single item.

Risk and Protective Factors

We report detailed results regarding risk and protective factors for the aforementioned mental health outcomes in Table 3. As shown, sociodemographic factors, such as gender, age, education, marital status, and having children, as well as their association with mental health outcomes, were extensively investigated. However, results are mixed (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk and protective factors

| Variables | PTS | General psychological distress/psychiatric morbidity | Depressive symptoms | Insomnia symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | Perceived stress | Infection-related worries | Burnout |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic features | ||||||||

| Female gender |

− [8] |

− [19] + [39] |

+ [15••] | + [15••] |

− [31••] LA [42] |

+ [4, 44] | LA [30] | |

| Age |

− [44] + [40] |

LA [8, 22, 25, 26, 34, 41] |

LA [21] |

LA [21, 26] |

+ [28] LA [42] |

LA [44] |

||

| Education | LA [44] |

LA [25] |

LA [31••] | + [44] | ||||

| Being married | LA [8, 22, 37, 41, 44] | LA [8, 22, 25, 26, 34, 41] | − [23] | + [44] | ||||

| Having children | LA [22, 37] | LA [22] | ||||||

| Living with family/children |

− [18] LA [22] |

− [33] |

||||||

| Personality, coping strategies and clinical features | ||||||||

| Neuroticism | + [25, 26] | |||||||

| Dysfunctional attachment | + [25, 30] | |||||||

| Maladaptive coping | + [30] | + [30, 35] | + [30] | |||||

| Resilience indicators | − [34] | − [27] | ||||||

| Self-efficacy | − [45•] | − [13] | ||||||

| Psychiatric history | + [16] | + [38] | + [38] | |||||

| Traumatic and stressful life events | LA [44] | + [26] | + [23] | |||||

| Work-related features | ||||||||

| Occupation | LA [17] | LA [19, 30, 35] | LA [31••] | |||||

| Physicians | − [28] | − [11] | − [2, 11, 28, 42] | |||||

| Nurses | + [15••, 29, 35, 40] |

− [25] |

+ [15••] | + [15••] | + [15••] | + [28, 39, 42] | + [30] | |

| Other HCWs | + [11] | |||||||

| Years of experience | LA [42] | LA [30] | ||||||

| High-risk units |

LA [38] |

+ [30] LA [22] |

LA [21] |

+ [23, 31••, 38] |

+ [31••] LA [21] |

LA [31••] | + [28, 31••, 43] | + [28] |

| Conscription to HR units | + [6] | + [6, 39] | + [6] | |||||

| Altruistic acceptance of risk | − [44] | − [23] | − [44] | |||||

| Contact with affected patients | + [8, 15••, 18, 29, 40] |

+ [8] |

+ [15••] | + [15••] | + [15••] | + [12, 39] |

+ [10] LA [4] |

+ [27] |

| Quarantine |

LA [18] |

+ [30] |

+ [23] | + [10] | ||||

| Being infected/ relative or friend infected | + [44] | LA [23] | LA [42] | − [13] | ||||

| Confidence in protective measures |

− [30] |

LA [30] | − [9] | − [33] | − [27, 30] | |||

| Organizational support | − [30] |

LA [30] |

− [10] | − [10, 30] | ||||

| Training | − [30, 40] |

− [16] LA [30] |

− [30] | |||||

| Confidence in disease-related info | LA [37] | − [11] | ||||||

| Job-related stress |

+ [29] LA [30] |

+ [39] LA [30] |

LA [30] | |||||

| Risk perception | + [29, 36, 37, 44] | + [23] | + [42] | + [11, 33, 44] | + [10] | |||

| Stigma | LA [30] |

+ [34] LA [30] |

+ [33] | LA [30] | ||||

+, positive association; -, negative association; LA, lack of association

Of importance

Of major importance

Some studies investigated the role of personal variables, such as personality, attachment styles, coping strategies, and clinical features, on mental health outcomes. Specifically, neuroticism [25, 26], dysfunctional attachment [25, 30], and maladaptive coping [30, 35] were found to be risk factors for mental health outcomes. Additionally, resilience indicators (i.e., hardiness, vigor) [27, 34] and self-efficacy [13, 45•] were protective factors for mental health outcomes.

Few retrospective studies found that having a past psychiatric history [16, 38] and reporting traumatic and stressful life events [23, 26, 44] were risk factors for psychiatric disorders or symptoms, respectively.

Several work-related features were investigated as factors associated with mental health outcomes: occupation, years of professional experience, working in high-risk units, direct contact with affected patients, being quarantined, being infected, or having relatives/friends get infected, confidence in equipment and protective measures, perceived organizational support, perceived adequacy of training, disease-related risk perception, job-related stress, and confidence in disease-related information.

Four studies found that physicians were less worried and anxious about the infection, compared with other HCWs [2, 11, 28, 42]. Also, nurses reported higher perceived stress levels [28, 30, 39, 42], psychopathological symptoms [15••], and higher PTSD symptoms, compared with other HCWs [15••, 29, 35, 40].

The level of exposure to infection seems to affect psychological outcomes. Studies showed that HCWs in units at high risk of infection present more severe mental health outcomes, compared with HCWs in units at low risk of infection [4, 6, 22, 23, 28, 30, 31••, 37, 38, 44]. Interestingly, two studies found that being conscripted from a unit at low risk of infection to one at high risk of infection during an epidemic is a specific risk factor for worse mental health [6, 39]. Conversely, altruistically accepting the risk of infection is a protective factor [23, 44].

Similarly, direct contact with affected patients is a significant risk factor for all mental health outcomes [8, 12, 15••, 18, 27, 29, 39, 40].

With reference to more personal levels of exposure, studies show a trend for higher PTS and infection-related worries in HCWs who have been quarantined [3, 10, 44].

Two important organizational variables that emerge as protective factors for mental health outcomes are organizational support [10, 16, 30, 39] and perceived adequacy of training [16, 30, 40].

Confidence in equipment and infection control measures appears to be a protective factor for mental health outcomes related to daily stress, namely, burnout [27, 30], perceived stress [9], and infection-related worries [33], but not for general mental health [29, 30, 37].

Moreover, disease-related risk perception was associated with worse mental health outcomes [47, 11, 23, 29, 33, 36, 37, 42, 44].

Discussion

With this rapid review, we aimed to provide quantitative evidence on the potential maladaptive psychological outcomes in HCWs facing epidemic and pandemic situations and to identify potential risk and protective factors.

In describing the issues faced by HCWs responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, Kang et al. refers to “a high risk of infection and inadequate protection from contamination, overwork, frustration, discrimination, isolation, patients with negative emotions, a lack of contact with their families, and exhaustion” [47]. The evidence reviewed here, both related to the COVID-19 pandemic and to other previous epidemic/pandemic outbreaks, clearly confirms that facing such issues has a relevant psychological impact on HCWs responding to outbreaks.

In particular, during outbreaks, HCWs reported post-traumatic stress symptoms (11–73.4%), depressive symptoms (27.5–50.7%), insomnia (34–36.1%), severe anxiety symptoms (45%), general psychiatric symptoms (17.3–75.3%), and high levels of work-related stress (18.1–80.1%) [5, 6, 8, 11, 12, 15••, 24, 25, 33, 38, 39]. Among these psychopathological outcomes, anxious and post-traumatic reactions were the most extensively investigated, and results pointed to the high prevalence of such areas of symptomatology in HCWs facing epidemic/pandemic outbreaks. This is not surprising, given the traumatic nature of the situations to which HCWs are exposed in their everyday work during epidemic/pandemic outbreaks. Furthermore, concerning mental health suffering, HCWs are considered a high risk group even in non-pandemic times [48].

Evidence related to psychopathological outcomes also shows that these maladaptive reactions can be long-lasting. In fact, post-traumatic and depressive symptoms, as well as general psychological distress, were reported even after periods ranging from 6 months up to 3 years after the epidemic/pandemic outbreak [23, 30, 35, 40, 41, 44].

At a psychological level, the evidence reviewed shows that general stress, specific infection-related worries, and work-related stress are reported by HCWs facing epidemic/pandemic outbreaks. While stress and worries seem to be limited to the period of exposure to the outbreak, effects in terms of burnout can be long-lasting.

What Can We Do to Reduce the Negative Impact of Outbreaks in Terms of Psychological Distress?

During epidemic/pandemic outbreaks, HCWs are, of necessity, exposed to a situation that causes maladaptive psychological responses. However, in this review, we also provide evidence synthesis about personal and situational factors that showed to have an impact in determining the level of such maladaptive psychological responses.

In reviewing findings related to the role of sociodemographic factors, we did not find strong evidence suggesting that these personal factors make the difference in maladaptive psychological responses reported by HCWs. Instead, other personal factors are more consistently associated with poorer outcomes. HCWs with less effective coping abilities were more likely to report psychopathological responses, whereas those showing resilience were relatively less affected by the situation [27, 30, 34, 35]. Previous psychiatric history was also a predictor of higher maladaptive responses [16, 38].

A number of work-related features were associated with the level of maladaptive responses in HCWs. Results are particularly consistent in indicating that physicians are less psychologically affected than nurses in facing an epidemic/pandemic outbreak [2, 11, 28, 42]. This could be due to a higher physical contact with patients for nurses, as compared with physicians. Also, physicians could be more protected from these kinds of negative outcomes as a result of their longer training. Another situational factor that clearly emerges is the level of exposure to the epidemic/pandemic situation, with HCWs working in high-risk units (or being in contact with infected patients) reporting poorer psychological adjustment [4, 6, 22, 23, 28, 30, 31••, 37, 38, 44]. This is also consistent with results showing that higher risk perception is associated with higher maladaptive responses [10, 11, 23, 29, 33, 36, 37, 42, 44]. Considering work organization, confidence in protective measures, training, and organizational support were all related to less severe psychological outcomes [9, 10, 16, 27, 30, 33, 39, 40].

With these personal and situational factors in mind, we will try to provide some suggestions that can help reduce negative psychological responses of HCWs facing epidemic/pandemic outbreaks. These suggestions have the double aim of reducing the individual psychological burden of HCWs and strengthening the response capacity of healthcare systems.

Know Your HCW Workforce to Support and Enhance Resilience and Coping Strategies

Primary prevention should take place regularly, so that personal factors (e.g., past psychiatric history and difficulties in coping strategies) could be addressed. Such preventive interventions will result in a healthier workforce that will likely show better psychological responses in emergency situations, such as epidemic/pandemic outbreaks.

Training programs related to coping and resilience should be a regular part of HCWs’ training and continuing education programs. Resilience trainings for HCWs have shown to be of benefit to health professionals (for a review, see Cleary and colleagues [49]). Training courses designed to build resilience to the stress of working during a pandemic are available also in online formats (e.g., Maunder and colleagues [50]). Furthermore, a recent review [51•] provided evidence that predisaster training and education can improve employees’ confidence in their ability to cope with disasters. The need for training to enhance medical staff psychological skills was also recently underlined by Chen and colleagues in relation to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic outbreak [52].

Reserve a Special Attention to HCWs Working on the Frontline

During the COVID-19 outbreak, frontline medical staff was included in the first priority category identified by the Chinese Society of Psychiatry to deliver psychological crisis intervention and provide technical guidance [53].

In China, on the one hand, psychological intervention teams, comprising psychological assistance hotline teams, and group activities to release stress were implemented for medical staff. On the other hand, the shift system and online platforms with medical advice were offered to help workers [47, 52]. In a situation in which resources are limited, interventions should be focused, on a first stage, on frontline HCWs, since they are more likely to undergo maladaptive psychological consequences. Particular attention should be reserved to nurses, since results show that they are especially affected by a more intense physical exposure to infected patients.

Provide Adequate Protective Measures to HCWs

The evidence synthesized in our review leads to hypothesize that when HCWs are provided with protective measures that are perceived as adequate, their risk perception is lower, and this could result in lower adverse psychological outcomes.

An essential factor to improve collaboration seems to be trust between organizations and workers [54, 55]. The feeling of being protected is associated with higher work motivation [56]. Hence, physical protective materials [54], together with frequent provision of information, should be provided.

Organize Support Services That Can Be Delivered Online

In comparison to previous epidemics, during COVID-19 pandemic, internet and smartphones are widely available [24]; hence, online mental health education, online psychological counseling services, and online psychological self-help intervention systems may and should be developed.

The major strength of the present rapid review is that, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to provide quantitative evidence of the mental health impact in HCWs facing epidemic and pandemic outbreaks as well as to identify potential related risk and protective factors.

Limitations are present as well. First, given the rapid nature of this literature review, we were not able to provide a quality of reporting evaluation of the included studies, which should represent the next step for a deeper understanding of the present results. However, we qualitatively evaluated the studies. Some limitations are related to the characteristics of the included studies: (1) the number of longitudinal studies was limited, and the majority were retrospective ones; (2) we found a great variability in the prevalence estimates, probably due to different cut-off scores used to identify cases (e.g., IES-R) and to the use of heterogeneous instruments (e.g., stress perception); (3) it is possible that cultural differences in health beliefs, display of mental symptoms, and different healthcare systems have influenced the results of the studies included in this review; and (4) some risk and protective factors are still understudied in relation to psychological responses to epidemic/pandemic outbreaks; for example, perceived social support was investigated only by one recent study on COVID-19 [45•], despite evidence highlighting its protective role for mental health outcomes [46].

Conclusions

Our review confirms that HCWs responding to epidemic/pandemic outbreaks show a number of negative mental health and psychological consequences. Such sequelae are particularly alarming when considering their long-lasting nature and their plausible association with impaired decision-making capacities. As a matter of fact, we cannot avoid the exposure of HCWs to critical situations that could be detrimental for their mental health, since their rapid and effective deployment is critical in confronting epidemic/pandemic outbreaks. However, failing to consider the negative psychological impact that these workers suffer would result in consequences both at the individual level and in the healthcare response capacity at a systemic level.

We presented evidence that points to a number of personal and situational factors that play a role in mitigating or exacerbating the maladaptive consequences suffered by HCWs. Following empirical evidence, we proposed that assessment and promotion of coping strategies and resilience, special attention to frontline HCWs, provision of adequate protective supplies, and organization of online support services could be ways to mitigate the negative psychological responses of HCWs responding to epidemic/pandemic outbreaks.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 11.6 kb)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Personality Disorders

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.World Health Organization. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. World Health Organization 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/258698/1/9789241512763-eng.pdf

- 2.Alsubaie S, Hani Temsah M, Al-Eyadhy AA, Gossady I, Hasan GM, Al-Rabiaah A, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus epidemic impact on healthcare workers’ risk perceptions, work and personal lives. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2019;13(10):920–926. doi: 10.3855/jidc.11753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai YM, Lin CC, Lin CY, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(9):1055–1057. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bukhari EE, Temsah MH, Aleyadhy AA, Alrabiaa AA, Alhboob AA, Jamal AA, et al. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak perceptions of risk and stress evaluation in nurses. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2016;10(8):845–850. doi: 10.3855/jidc.6925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan SSC, Leung GM, Tiwari AFY, Salili F, Leung SSK, Wong DCN, et al. The impact of work-related risk on nurses during the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. Fam Community Heal. 2005;28(3):274–287. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CS, Wu HY, Yang P, Yen CF. Psychological distress of nurses in Taiwan who worked during the outbreak of SARS. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(1):76–79. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen NH, Wang PC, Hsieh MJ, Huang CC, Kao KC, Chen YH, et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome care on the general health status of healthcare workers in Taiwan. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(1):75–79. doi: 10.1086/508824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, Lee CY, Chiu NM, Yeh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185(1):127–133. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chua SE, Cheung V, Cheung C, McAlonan GM, Wong JWS, Cheung EPT, et al. Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high-risk health care workers. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(6):391–393. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiksenbaum L, Marjanovic Z, Greenglass ER, Coffey S. Emotional exhaustion and state anger in nurses who worked during the sars outbreak: the role of perceived threat and organizational support. Can J Community Ment Heal. 2006;25:89–103. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2006-0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goulia P, Mantas C, Dimitroula D, Mantis D, Hyphantis T. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:322. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grace SL, Hershenfield K, Robertson E, Stewart DE. The occupational and psychosocial impact of SARS on academic physicians in three affected hospitals. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(5):385–391. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho SMY, Kwong-Lo RSY, Mak CWY, Wong JS. Fear of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) among health care workers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(2):344–349. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji D, Ji YJ, Duan XZ, Li WG, Sun ZQ, Song XA, et al. Prevalence of psychological symptoms among Ebola survivors and healthcare workers during the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(8):12784–12791. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease. JAMA. 2019;3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lancee WJ, Maunder RG, Goldbloom DS. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Toronto hospital workers one to two years after the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(1):91–95. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee AM, Wong JGWS, McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Sham PC, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:233–240. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho AR, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;87:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Wan C, Ding R, Liu Y, Chen J, Wu Z, et al. Mental distress among Liberian medical staff working at the China Ebola Treatment Unit: a cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0341-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Ge J, Yang M, Feng J, Qiao M, Jiang R, et al. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medial teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;S0889-1591(20):30309–30303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang Y, Chen M, Zheng X, Liu J. Screening for Chinese medical staff mental health by SDS and SAS during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Psychosom Res. 2020;133:16–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin CY, Peng YC, Wu YH, Chang J, Chan CH, Yang DY. The psychological effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome on emergency department staff. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(1):12–17. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.035089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, Fan B, Fang Y, Kong J, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang YT, Liu Z, Hu S, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu YC, Shu BC, Chang YY, Lung FW. The mental health of hospital workers dealing with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(6):370–375. doi: 10.1159/000095443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lung FW, Lu YC, Chang YY, Shu BC. Mental symptoms in different health professionals during the SARS attack: a follow-up study. Psychiatr. 2009;80(2):107–116. doi: 10.1007/s11126-009-9095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marjanovic Z, Greenglass ER, Coffey S. The relevance of psychosocial variables and working conditions in predicting nurses’ coping strategies during the SARS crisis: an online questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(6):991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuishi K, Kawazoe A, Imai H, Ito A, Mouri K, Kitamura N, et al. Psychological impact of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on general hospital workers in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;66(4):353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Rourke S, Hunter JJ, Goldbloom D, Balderson K, et al. Factors associated with the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on nurses and other hospital workers in Toronto. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):938–942. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145673.84698.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, Bennett JP, Borgundvaag B, Evans S, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1924–1932. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.•• McAlonan GM, Lee AM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Tsang KWT, Sham PC, et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can J Psychiatry, This study is important for its longitudinal and case-control design. 2007;52(4):241–7. 10.1177/070674370705200406. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Mohammed A, Sheikh TL, Gidado S, Poggensee G, Nguku P, Olayinka A, et al. An evaluation of psychological distress and social support of survivors and contacts of Ebola virus disease infection and their relatives in Lagos, Nigeria: a cross sectional study - 2014. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2167-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, Al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. 2004;170(5):793–798. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JS, Lee EH, Park NR, Choi YH. Mental health of nurses working at a government-designated hospital during a MERS-CoV outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32(1):2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phua DH, Tang HK, Tham KY. Coping responses of emergency physicians and nurses to the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(4):322–328. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Son H, Lee WJ, Kim HS, Lee KS, You M. Hospital workers’ psychological resilience after the 2015 Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak. Soc Behav Personal. 2019;47(2):1–13. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Styra R, Hawryluck L, Robinson S, Kasapinovic S, Fones C, Gold WL. Impact on health care workers employed in high-risk areas during the Toronto SARS outbreak. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(2):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su TP, Lien TC, Yang CY, Su YL, Wang JH, Tsai SL, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and psychological adaptation of the nurses in a structured SARS caring unit during outbreak: a prospective and periodic assessment study in Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(1-2):119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tam CWC, Pang EPF, Lam LCW, Chiu HFK. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hongkong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2004;34(7):1197–1204. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang L, Pan L, Yuan L, Zha L. Prevalence and related factors of post-traumatic stress disorder among medical staff members exposed to H7N9 patients. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;4(1):63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tham KY, Tan YH, Loh OH, Tan WL, Ong MK, Tang HK. Psychological morbidity among emergency department doctors and nurses after the SARS outbreak. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2005;12(5):215–223. doi: 10.1177/102490790501200404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong TW, Yau JKY, Chan CLW, Kwong RSY, Ho SMY, Lau CC, et al. The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12:13–18. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200502000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong SYS, Wong ELY, Chor J, Kung K, Chan PKS, Wong C, et al. Willingness to accept H1N1 pandemic influenza vaccine: a cross-sectional study of Hong Kong community nurses. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(5):302–311. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e923549. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsai AC, Lucas M, Kawachi I. Association between social integration and suicide among women in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(10):987–993. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):e14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, Dambrun M, Moustafa F, Mermillod M, et al. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):1–28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cleary M, Kornhaber R, Thapa DK, West S, Visentin D. The effectiveness of interventions to improve resilience among health professionals: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;71:247–263. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Mae R, Vincent L, Peladeau N, Beduz MA, et al. Computer-assisted resilience training to prepare healthcare workers for pandemic influenza: a randomized trial of the optimal dose of training. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:72. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]