Abstract

Purpose:

To report clinical characteristics of Demodex blepharokeratoconjunctivitis affecting young patients.

Methods:

This is a retrospective review of 14 patients with the history of chronic red eyes with corneal involvement. All patients were diagnosed with ocular demodicosis based on the results of eyelash sampling. All patients were treated with 50% tea tree oil lid scrubs and two doses of oral ivermectin (200 mcg/kg).

Results:

The median age of patients at diagnosis was 27 years (range: 11–39 years). The duration of symptoms ranged from 2 months to 20 years. Rosacea was present in only three patients. Four patients had best corrected visual acuity less than 20/60. Allergic conjunctivitis (n = 7) and viral keratitis (n = 5) were the most common misdiagnosis previously made. Cylindrical dandruff was present in only six patients and eyelashes were clean in rest of them. Inferior vascularization was present in eight eyes, superior in seven eyes, and corneal scars were present in 12 eyes. Four patients had steroid-related complications. All patients, except one responded to tea tree oil treatment and 13 patients were off steroids after 3 weeks of starting the treatment.

Conclusion:

Demodex infestation of eyelids can lead to chronic blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in healthy pediatric and young adult patients who otherwise have good hygiene, which can often be overlooked or misdiagnosed. Viral keratitis and allergic conjunctivitis are common misdiagnoses and demodicosis can be confirmed by simple epilation. Early diagnosis and treatment can prevent long-term steroid use and its related complications.

Keywords: Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis, chronic red eye, Demodex, misdiagnosis, tea tree oil

Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis (BKC) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the lid margin with secondary conjunctival and corneal involvement. The pathogenesis of this disorder is largely unclear, with few studies suggesting colonization of lid margins with bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Propionibacterium acnes as the causative factors for BKC.[1,2] Young patients with chronic red eye and corneal vascularization are often diagnosed as atopic or allergic disease or even herpetic disease and are chronically treated with steroids and develop unavoidable grave complications of the treatment.

Historically, literature has been reported on Demodex over 176 years ago with ophthalmic literature dating back to 1967.[3] Ophthalmologically, Demodex species have been implicated in some pathologies, most common being blepharitis.[4] Other associations include madarosis, trichiasis, chalazia, pterygium, floppy eyelids, and basal cell carcinoma.[5,6,7,8] However, corneal manifestation of Demodex infestation in young patients has been reported recently, highlighting the importance of Demodex as a causative agent for chronic inflammation of the ocular surface, including corneal involvement.[9,10]

We present a case series of 26 eyes of 14 patients wherein we were able to identify the cause of the pathology and describe clinical characteristics.

Methods

We conducted a single-center observational study from April 2017 to December 2018. Patients with a diagnosis of demodicosis based on eyelash sampling and with corneal manifestations were included in the study. Sociodemographic data including age, sex, economic status, and general hygiene were noted. Medical history was noted for any previous treatment taken, duration of previous treatment, response to previous treatment, and current complaints. Complete ocular examination was done including best corrected visual acuity, anterior segment examination noting the presence of blepharitis with or without cylindrical dandruff (CD), the presence of conjunctival inflammation, corneal signs with quadrant of corneal vascularization, laterality, opacities, thinning and infiltrate; lens status, presence of glaucoma, and retinal pathology were also noted.

Once clinical suspicion of demodicosis was made, eyelash sampling was done after taking informed consent forms from the patients. Eyelashes with CDs were preferred.[11] In the absence of CDs, those eyelashes were chosen which had fine cream-colored bristles protruding from the undersurface of the opening of the eyelash follicle.[12] At least two nonadjacent eyelashes were taken from each of the lids. We used the method described by Mastrota et al. of rotating the eye lash before epilating for better yield of mites.[13] Eyelashes were placed on two different slides, right and left and were evaluated under light microscope. Fluorescein strip moistened with 0.9% normal saline was placed at the edge of the cover slip to dissolve the debris around the mites.[14] After a waiting period of 5 min, a single examiner examined the slides under 20X magnification for identification of mites. The presence of Demodex mites on any eyelash was considered positive. External photography of the lid margins and the cornea was done.

Once diagnosed with demodicosis, patients were treated with equal concentration of tea tree oil and olive oil lid scrubs and two doses of oral ivermectin (200 μg/kg, 1 week apart).[15] Fluorometholone (0.1%) eye drops were prescribed in tapering dosage for 3 weeks along with the topical lubricants. Patients were explained the method of using tea tree oil twice daily for 3 months and were asked to follow-up at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months. Thereafter, patients were asked to continue lid scrubbing with tea tree oil on weekly basis depending on the response and chronicity.

On follow-up, patients were evaluated for symptomatic relief and decrease in ocular surface inflammation in terms of congestion and corneal vascularization.

The study was approved by the institutional review board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

During the study period of April 2017 to December 2018, 49 patients were positive for Demodex mites in eyelash sampling. 26 eyes of 14 patients had corneal findings and were included in the study [Table 1]. Median age was 27 years (range: 11–39 years) and included 11 males and 3 females. The median age from the beginning of symptoms was 17.5 years (range: 8–30.6 years). Only one of the 14 patient availed nonpaying services of the hospital, while the rest belonged to a high socioeconomic status with good personal hygiene.

Table 1.

Clinical information of patients with Demodex blepharokeratoconjunctivitis

| Case no | Age | Sex | Symptoms | Duration of symptoms | Rosacea | Corrected visual acuity (VA) | Cylindrical dandruff | Corneal findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right eye | Left eye | |||||||||

| 1 | 31 | M | redness, pain | 6 months | No | 20/20 | 20/20 | Yes (diffuse) | inferior vascularization | minimal inferior vascularization |

| 2 | 14 | F | redness, itching | 5 years | No | 20/20 | 20/20 | Yes (diffuse) | inferior vascularization | inferior vascularization, phlycten |

| 3 | 23 | M | redness, ocular irritation, DOV, photophobia | 10 years | No | 20/60 | 20/80 | No | 360 vascularization with corneal scars | 360 vascularization with corneal scars |

| 4 | 24 | M | redness, ocular irritation, DOV | 12 years | Yes | 20/20 | 20/20 | No | superior vascularization + scar | superior vascularization + scar |

| 5 | 11 | M | redness, itching | 3 years | No | 20/20 | 20/20 | Yes (sporadic) | superior vascularization, infiltrate | normal |

| 6 | 29 | M | Redness, Itching, dropping of eyelids | 12 years | No | 20/20 | 20/20 | No | superior vascularization | superior vascularization |

| 7 | 30 | M | redness, pain, DOV | 2 years | No | 20/80 | 20/20 | No | PUK | scar |

| 8 | 23 | F | redness, ocular irritation, DOV, photophobia | 5 years | No | 20/20 | 20/20 | Yes (sporadic) | 360 vascularization | inferior vascularization |

| 9 | 25 | F | redness, ocular irritation, DOV | 10 years | No | 20/40 | 20/30 | Yes (sporadic) | 360 vascularization | 360 vascularization |

| 10 | 35 | M | redness, ocular irritation, photophobia | 20 years | No | 20/30 | 20/20 | No | corneal scar | corneal scar |

| 11 | 31 | M | redness, DOV | 1 year | No | 20/30 | 20/400 | No | corneal scar | inferior vascularization, infiltrates |

| 12 | 28 | M | redness, ocular irritation, DOV, photophobia | 3 years | Yes | 20/120 | 20/20 | Yes (sporadic) | superior vascularization, infiltrate, scar | corneal scar |

| 13 | 39 | M | redness, ocular irritation | 12 years | No | 20/20 | 20/20 | No | superior vascularization, scar | inferior vascularization, scar |

| 14 | 23 | M | redness | 1 year | Yes | 20/20 | 20/20 | No | normal | inferior vascularization |

DOV: Diminution of vision

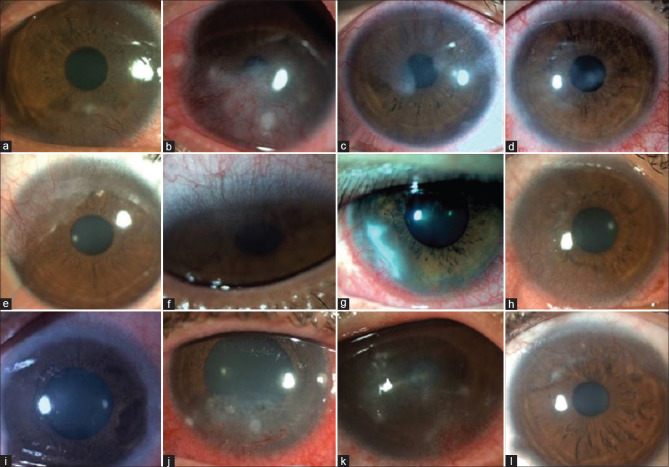

All the patients included in the study had a chronic history of relentless, refractory red eyes with median duration of symptoms being 5 years (range: 2 months to 20 years) [Fig. 1]. Six patients had history of more than 10 years and only two patients had history less than 6 months. Only 2 patients had unilateral findings, rest all had bilateral.

Figure 1.

Photographs with different corneal findings. Presence of either inferior, superior or all-around corneal vascularisation( a-l); active infiltrates(a, b, j, k) or scars (c, d , h , i, l); phlycten (b) and peripheral ulcerative keratitis (g)

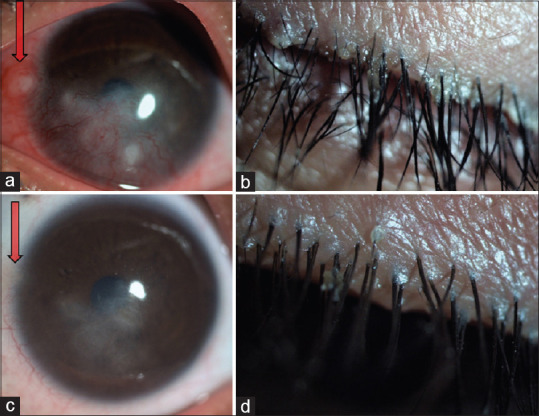

Most common symptom was redness (n = 14), present in all of the fourteen patients, followed by ocular irritation (n = 8), diminution of vision (n = 7), photophobia (n = 4), itching (n = 3), pain (n = 2), and drooping of eyes (n = 1). Best corrected visual acuity was less than 20/60 in four eyes. Before the diagnosis of demodicosis was made, all the patients had multiple misdiagnosis such as vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) (n = 7), viral keratitis (n = 5), phlyctenular KC (n = 3) [Fig. 2], limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) (n = 1), superior limbic keratitis (n = 1), episcleritis (n = 1), Terrien's degeneration (n = 1), dry eye (n = 1), acanthamoeba keratitis (n = 1), bacterial keratitis (n = 2), and microsporidiosis (n = 1). Three patients had facial rosacea. As they were misdiagnosed earlier, they had received various other treatments such as topical and oral steroids, oral azathioprine, topical ciclosporin, topical tacrolimus, antivirals, antibiotics, antifungals, antiamebicidal, and oral antitubercular therapy. All patients had received chronic steroid therapy, with four patients manifesting steroid induced side effects with advanced glaucoma (n = 2) and cataract (n = 2, one operated). Three patients were using scleral contact lenses, one of whom had developed giant papillary conjunctivitis due to chronic use. None of the other patients had papillae in upper tarsal conjunctiva excluding the diagnosis of allergic conjunctivitis.

Figure 2.

Patient misdiagnosed as a case of phlyctenular conjunctivitis. Patient had phlycten-like nodule at 9 o'clock (arrow in a) and florid inferior vascularization (a) with diffuse cylindrical dandruff (b). Treatment with tea tree oil lid scrubs and oral ivermectin resulted in resolution of phlycten (arrow in c) and regression of vascularization. Eyelashes also showed improvement (d)

CDs were present in 6 patients at the time of diagnosis. Eight eyes had inferior vascularization, seven eyes had superior vascularization, and five eyes had vascularization in all quadrants. Twelve eyes had corneal scars; three had marginal infiltrates; phlycten and peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) in one eye each.

We treated all these patients with tea tree oil and oral ivermectin. At the end of 3 months all patients showed clinical improvement in signs and symptoms. Thirteen patients were off topical steroids after 3 weeks of initial treatment. One patient had recurrence on tea tree oil therapy and needed topical steroids in low dosage during the study period. Patient with PUK had resolved within 3 weeks with residual scarring.

Representative case

Case 3

A 13-year-old boy presented to us 8 years back with history of redness, itching and diminution of vision in both eyes of 2 years duration. He was diagnosed with allergic KC elsewhere and was treated with topical steroids and ciclosporin eye drops. He continued to have several episodes of redness with marginal keratitis and increasing corneal vascularization. In 2012, we thought it was viral keratitis and treated him for the same for some time, but he did not show improvement. Subsequently, he had an episode of phlyctenular conjunctivitis and was investigated for tuberculosis, an association of which is not uncommon in Indian context. However, he did not show evidence of tuberculosis and he continued to have episodes of ocular surface inflammation that were managed by topical steroids. He was prescribed scleral contact lenses to improve his vision. In 2015, he developed steroid-induced glaucoma and was managed on antiglaucoma medication. After 10 years of the disease, he was suspected to have demodicosis and eyelash sampling confirmed the disease. Six months of therapy with tea tree oil has made him symptom-free with no evidence of recurrence [Fig. 3].

Figure 3.

Representative case 3. Right eye (a) showing diffuse conjunctival inflammation and corneal scars. With 10 years history of multiple misdiagnosis and treatments, eyelashes were clean (b), without any cylindrical dandruff. Tea tree oil therapy resulted in significant reduction in conjunctival inflammation (c)

All of our cases were young, suffering from chronic BKC and had undergone multiple consultations. These cases were diagnostic dilemmas and were treated for long time with topical steroids. It did not occur to us to sample the eyelashes earlier even though half of them had CD on eyelashes. When eyelash sampling was done it came out to be positive for Demodex mites. Recurrence rates reduced after treatment with tea tree oil and patients were symptomatically better.

Discussion

Our case series demonstrate the presence of Demodex mite in eyelashes as a cause of BKC in young and healthy patients, even with good general hygiene. The disease was chronic in nature, causing severe vision impairment in many patients due to corneal scarring and vascularization or complication of steroid usage. In most cases, it took several years before the diagnosis of demodicosis could be confirmed.

While it is well-established that prevalence of Demodex in eyelashes increases with age, our series had corneal manifestation of demodicosis in young individuals.[16] Liang et al. have also described keratitis in the presence of Demodex infestation in pediatric and young patients.[17,18] It is known that greatest concentration of Demodex mite is found where sebaceous glands are numerous.[19] As demodices are voracious maters, males travel from one hair follicle to other in search of female mites. Thus, the concentration of mites would be greater where the density of follicles is higher such as facial areas. During adolescence, sebum production increases under the influence of sex hormones, especially in the facial area, including eye lashes.[20] Thus, it is possible that mites migrate from facial area to eye lashes in search of a conducive environment, causing manifestation of BKC in young individuals. Mites may incite hypersensitivity reaction in younger people and as age advances, immunity fades and the mites just colonize and survive in harmony.[21,22,23]

Presence of CDs increases the yield of Demodex.[11] In the study conducted by Kheirkhah et al., equal number of patients had diffuse and sporadic CDs.[9] Whereas all the pediatric patients with blepharoconjunctivitis in Liang et al.'s study had sporadic CDs.[17] In our case series, CDs were absent in eight patients and diffuse in only two patients. Earlier studies and the present study make a suggestion that CDs may or may not be present in patients with corneal manifestation.

It is believed that Demodex proliferate in eyelashes as eyes being surrounded by protruding structures such as eyebrows, nose, and cheeks are not accessible to cleaning during daily hygiene.[24] Lee et al. have suggested association between hygiene and Demodex counts while determining relationship between Demodex infestation and ocular discomfort.[25] Otherwise, studies have not been conducted with respect to hygiene and Demodex infestations of eyelashes. As noted earlier, CDs were absent in more than half of our patients suggesting that hygiene may only be one of the contributing factor in colonization and pathogenicity of Demodex BKC.

Most patients had several years of empirical treatment before the etiology of demodicosis could be confirmed. Like in previous studies, viral keratitis and allergic conjunctivitis were the most common misdiagnosis. Our series emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis to reduce vision loss due to corneal scarring and steroid-induced complications. All patients in our series had vascularization while only two pediatric patients reported by Liang et al. had corneal vascularization. Vascularization of the cornea increases with the chronicity of the disease. Superior and inferior distribution of vascularization can be explained by the fact that the chemical mediators secreted by Demodex spread over the cornea as the eyelids rub them during blinking and causes inflammation in either the superior or inferior part of the cornea.

Tea tree oil is widely used in cosmetics and for various skin ailments including acne and rosacea. Tea tree oil has been shown to reduce Demodex infestation and ocular symptoms related to it.[26] Terpinen-4-ol is the most active ingredient responsible for the anti-inflammatory effects.[27] Previous studies and our results strongly suggest that the use of tea tree oil minimizes the need of long-term steroids and can prevent serious complications associated with it.

Our study and existing literature suggest that Demodex BKC is a clinical spectrum primarily involving lid margins and has varied manifestations across different age groups. Demodex probably starts colonizing eyelashes early in life inciting humoral immunity and causing ocular surface inflammation. Early diagnosis is a challenge as clinical presentation is often confusing. Demodex as cause of ocular surface inflammation should always be kept in mind in patients with marginal keratitis, peripheral scarring, and vascularization involving superior or inferior quadrants with or without CDs.

Our study had few limitations. We did not differentiate between Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis which could have helped us in better understanding of the disease. D. brevis is difficult to isolate with the standard epilation technique as they are very few in number and buried deep within the sebaceous glands. Demodex count per eyelash was not taken into consideration as with clinical experience we realized that epilation does not yield all the mites. Better diagnostic techniques are required to help in associating the link between Demodex mite and corneal disease. Our series does not include patients of BKC where demodicosis was suspected but eyelash sampling was negative for the mite. Age- and sex-matched population-based studies are also required to know the incidence of Demodex in asymptomatic population and to prove its association in those affected.

In his paper, Coston states “often several ophthalmologists have been consulted who have said: 'I find nothing to explain your symptoms'. Many patients have been tranquilized, 'dropped', 'steroided', and called neurotic, because the ophthalmologist did not think of Demodex or know how to find and treat them.“[3] The paper was published in 1967, and we believe that the statements made at that time still hold true and ophthalmologists should search for Demodex as a cause for chronic red eye and keratitis.

Conclusion

Demodex infestation of eyelids causes chronic blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in healthy children and young adults. It is often missed or is misdiagnosed as viral keratitis or allergic conjunctivitis. Demodicosis can be confirmed by simple epilation and microscopy. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment is gratifying.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understand that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gupta N, Dhawan A, Beri S, D’Souza P. Clinical spectrum of pediatric blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. J AAPOS. 2010;14:527–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teo L, Mehta JS, Htoon HM, Tan DT. Severity of pediatric blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in Asian eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:564–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coston TO. Demodex folliculorum blepharitis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1967;65:361–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao YE, Wu LP, Hu L, Xu JR. Association of blepharitis with Demodex: A meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19:95–102. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2011.642052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang L, Ding X, Tseng SC. High prevalence of Demodex brevis infestation in chalazia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:342–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang Y, He H, Sheha H, Tseng SC. Ocular demodicosis as a risk factor of pterygium recurrence. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Nouhuys HM, van den Bosch WA, Lemij HG, Mooy CM. Floppy eyelid syndrome associated with Demodex Brevis. Orbit. 1994;13:125–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erbagci Z, Erbagci I, Erkiliç S. High incidence of demodicidosis in eyelid basal cell carcinomas. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:567–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kheirkhah A, Casas V, Li W, Raju VK, Tseng SC. Corneal manifestations of ocular Demodex infestation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:743–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo X, Li J, Chen C, Tseng S, Liang L. Ocular demodicosis as a potential cause of ocular surface inflammation. Cornea. 2017;36(Suppl 1):S9–14. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao YY, Di Pascuale MA, Li W, Liu DTS, Baradaran-Rafii A, Elizondo A, et al. High prevalence of Demodex in eyelashes with cylindrical dandruff. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3089–94. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hom MM, Mastrota KM, Schachter SE. Demodex: Clinical cases and diagnostic protocol. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:e198–205. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182968c77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mastrota KM. Method to identify Demodex in the eyelash follicle without epilation. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:e172–4. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318294c2c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kheirkhah A, Blanco G, Casas V, Tseng SC. Fluorescein dye improves microscopic evaluation and counting of Demodex in blepharitis with cylindrical dandruff. Cornea. 2007;26:697–700. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31805b7eaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holzchuh FG, Hida RY, Moscovici BK, Albers MBV, Santo RM, Kara-Jose N, et al. Clinical treatment of ocular Demodex folliculorum by systemic ivermectin. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:1030–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biernat MM, Rusiecka-Ziółkowska J, Piątkowska E, Helemejko I, Biernat P, Gościniak G. Occurrence of Demodex species in patients with blepharitis and in healthy individuals: A 10-year observational study. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2018;62:628–33. doi: 10.1007/s10384-018-0624-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang L, Safran S, Gao Y, Sheha H, Raju VK, Tseng SC. Ocular demodicosis as a potential cause of pediatric blepharoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2010;29:1386–91. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181e2eac5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang L, Liu Y, Ding X, Ke H, Chen C, Tseng SC. Significant correlation between meibomian gland dysfunction and keratitis in young patients with Demodex brevis infestation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:1098–102. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rufli T, Mumcuoglu Y. The hair follicle mites Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis: Biology and medical importance. A review. Dermatologica. 1981;162:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000250228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaller M, Plewig G. Structure and function of eccrine, apocrine, and sebaceous glands. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizza JL, Schaffer JV, editors. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012. pp. 539–44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholls SG, Oakley CL, Tan A, Vote BJ. Demodex species in human ocular disease: New clinicopathological aspects. Int Ophthalmol. 2017;37:303–12. doi: 10.1007/s10792-016-0249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacey N, Russell-Hallinan A, Zouboulis CC, Powell FC. Demodex mites modulate sebocyte immune reaction: Possible role in the pathogenesis of rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:420–30. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bevins CL, Liu FT. Rosacea: Skin innate immunity gone awry? Nat Med. 2007;13:904–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0807-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacey N, Kavanagh K, Tseng SC. Under the lash: Demodex mites in human diseases. Biochem (Lond) 2009;3:2–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SH, Chun YS, Kim JH, Kim ES, Kim JC. The relationship between Demodex and ocular discomfort. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2906–11. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao YY, Di Pascuale MA, Elizondo A, Tseng SC. Clinical treatment of ocular demodicosis by lid scrub with tea tree oil. Cornea. 2007;26:136–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000244870.62384.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tighe S, Gao YY, Tseng SC. Terpinen-4-ol is the most active ingredient of tea tree oil to kill Demodex mites. Trans Vis Sci Tech. 2013;2:2. doi: 10.1167/tvst.2.7.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]