Abstract

Objective

We examined the preliminary acceptability and efficacy of family-based therapy (FBT) for weight restoration in young adults (FBTY) with Anorexia Nervosa (AN).

Method

Twenty-two primarily female participants ranging from age 18 to 26, with AN or atypical AN (ICD-10) and their support adults were enrolled in a 6-month open trial of FBTY. Participants were assessed at baseline, after treatment, and at six and 12 month follow-up visits. The primary outcome was BMI and secondary outcomes included eating disorder psychopathology, current eating disorder obsessions, and compulsions, number of other Axis I disorders and global assessment of functioning.

Results

Although FBTY was rated as suitable by participants and their support adults, during FBTY, 9/22 participants dropped out and 3/22 dropped out at follow-up assessments. Despite being offered 18–20 sessions over six months, a mean of 12 FBTY sessions (SD = 6) were attended. After FBTY, 15 of the intent-to-treat sample of 22 were no longer underweight (BMIs ≥ 19 kg/m2) and 12 months after treatment, 13/22 were no longer underweight. The magnitude of the BMI increase during FBTY (Hedges g = 1.20, 95th percentile CI = 0.55–1.85) was comparable to findings for adolescent FBT for AN. Secondary outcomes also improved.

Discussion

FBTY for young adults with AN and atypical AN, which involves support adults participants have chosen, results in weight restoration that is sustained up to a year after treatment.

Keywords: anorexia, family-based therapy, school mandated treatment, readiness to change

Introduction

Anorexia Nervosa (AN), an eating disorder characterized by ego-syntonic life-threatening starvation, has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric illness.1 Among available treatments, none shows clear superiority for adult AN and most have high dropout rates. However, family-based therapy (FBT) or Maudsley Family Therapy for adolescents with AN has the most empirical support for its efficacy. FBT for adolescent AN results in weight restoration for at least 50–60% of patients within a year2 and weight maintenance 2–4 years later.3 After family treatment, AN remission rates are greater than those following standard care and other psychotherapies.4 At follow-up, FBT for adolescent AN and bulimia nervosa generally have better remission than individual psychotherapy.5 The largest adolescent AN multisite trial showed that FBT caused more rapid weight restoration, resulted in fewer hospital stays and was more cost-effective than systemic family therapy which addresses problems in the family unit rather than the eating and weight of the patient.6 However, to date, FBT has only been systematically used in adolescents with AN.

FBT for adolescent AN focuses on weight restoration, presents a nonblaming stance regarding the etiology of AN, separates the illness from the client, and empowers parents.7 Treatment involves 16 to 18 sessions administered over six to nine months. Phase 1 involves parents taking charge of weight restoration. Phase 2 allows clients gradual control over eating and Phase 3 addresses developmental issues include fostering autonomy from parents.

Although treatment adaptations typically move downwards in age, adapting an adolescent treatment for young adults is defensible given that transitioning to independence takes longer than in previous generations.8 In the 1960s, 30% of 20 year-old women were financially independent, married and had a child; in 2000, only 6% of same-aged women experienced these transitions.9 Given the efficacy of FBT for adolescent AN, the need for improved treatment for adult AN, continued dependence of young adults on parents, and consistent with clinician’s report of the need to adapt FBT for young adults,10 FBT was adapted for young adults with AN (FBTY).11

The aim of this study was to examine the preliminary acceptability and efficacy of FBTY using an open trial design. Our first prediction was that FBTY, although adapted from an adolescent treatment program, was acceptable to young adult participants and their chosen support adult or adults. Support adults could include partners, family members, close friends, or roommates. These individuals were defined as adults whom young adult participants either regarded as emotionally invested in them or upon whom the participant was financially dependent. Acceptability was assessed by treatment dropout rate, suitability ratings, and number of therapy sessions attended. Because FBTY focused on weight restoration, the second prediction was that FBTY will lead to weight restoration by the end of treatment and at six and 12 months follow-up visits. Our third prediction was that FBTY would reduce eating disorder psychopathology, eating-related obsessions, and compulsions, other Axis I disorders, and improve global functioning.12

Method

The FBTY trial and follow-up was conducted from September 2010 to March 2014 in an outpatient eating disorder program after approval by the university hospital institutional review board. Potential participants were recruited through the student health and counseling service at the University and through letters to local eating disorders clinics. After initial inquiries, potential young adult clients were required to complete a phone screen before an in-person visit with their support adults. Participation in the treatment trial was free of charge.

Participants

We included adults 18–26 years old, with BMI ≥ 16.5 kg/m2, who met criteria for ICD-10 AN or atypical AN diagnoses.13 We included individuals who were deemed medically stable for outpatient treatment by their own or the study physician, with at least one support adult willing to consent and participate in the study. Participants were not excluded if they had a history of hospitalization for their eating or other psychological disorders. Participant exclusion criteria were physical/psychological problems requiring hospitalization, current drug and alcohol dependence, physical conditions influencing eating and weight, and past FBT. Participants were eligible if stable on psychotropic medications for at least two months. Participants were withdrawn if pregnant or needing >72 hours of hospitalization, for example, for weight restoration.

Measures

Participants were assessed on outcome measures at baseline, mid-treatment, after treatment, and during 6 and 12 months follow-up visits.

The primary outcome, BMI, was calculated using measured weight and height at each outcome assessment and therapy session.

Secondary outcomes were eating disorder psychopathology, represented by the global score of the Eating Disorders Examination 16th edition (EDE),14 a structured standardized interview assessing the frequency and severity of eating disorder behaviors. Other secondary outcomes were current eating disorder obsessions and compulsions assessed by an interview, the Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scale (YBCEDS)15 and number of other Axis I disorders assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV: Axis I Disorders16; the Longitudinal Interview Follow-up Evaluation-Psychiatric Status Ratings17; and global assessment of functioning.12 Standardized interviews were chosen for their high diagnostic reliability and validity.

Treatment suitability was assessed after FBTY using scales ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 = “not at all,” 5 = “moderately,” and 10 = “completely” in response to the question: “How suitable do you think this treatment is for your problem (or in the case of support adults, “for your family member or friend”)?” These scales were administered to participants and their support adults separately.

School mandated treatment was defined as the participant being referred by the university health, counseling services, or administrators for treatment, and where university leave and where treatment for the AN was required before the student was allowed to return to university.

Readiness to change was assessed at baseline, at mid-treatment and after treatment with the AN Stages of Change Questionnaire (ANSOCQ), a 20-item measure with high reliability and validity.18 Participants selected the best statement of five that corresponded to their current stage of change for an eating disorder behavior or attitude. Higher total scores ranging from 0 to 100 denote greater readiness to change.

Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the potential predictors of weight restoration in FBTY. We used initial severity and individual readiness to change as individual predictors and presence of a school mandate as a system-level predictor of BMI change over time. The details of this analysis are in the online Supplementary.

FBTY Adults with AN

Participants were offered 18–20 FBTY sessions over six months. More sessions than in FBT for adolescent AN were offered to allow young adult participants enough time to select a support adult. Four adaptations were made for young adults.

First, participants could choose a support adult who was not a parent. Support adults were defined as one or more adult/s chosen by the participant, whom they regarded as emotionally invested in them, or upon whom the participant was financially dependent. Support adults included partners, family members, close friends, or room-mates.

Second, therapists developed a more collaborative approach with the young adult than was typical of adolescent FBT. The FBTY therapist’s goal was to create an alliance with the participant and support adult against the illness. While weight restoration was non-negotiable, the young adult could choose to participate in the decisions of how to return to regular activities like college. However, if their contribution did not lead to weight gain, these decisions returned to the support adult. Although the support adult assisted the participant in shopping, preparing, and eating meals, FBTY allowed the young adult more choice in where to eat and how the support adult/s could assist them in regaining weight.

Third, FBTY addressed developmental issues specific to young adults such as the transition from high school to college, given that AN could delay these milestones.

Fourth, unlike the final phase of FBT for adolescent AN, the final phase of FBTY provided the option to increase individual therapy session time without a support adult.

Therapists and Assessors

Therapists and assessors were clinicians with at least a Master’s degree. The two social workers and two PhD staff therapists, experienced in administering adolescent FBT in clinical trial settings, met for weekly case conferences. Assessors were independent from therapists and were three clinical psychology trainees with at least a year of experience conducting clinical trial assessments. They were trained to reliability on study interviews and met weekly for supervision. As a requirement of the study, participants met with their own physician or the study physician at least every two weeks during the course of the treatment study. Participants who were on psychotropic medications were required to see their own psychiatrist or the study psychiatrist regularly over the course of the treatment study.

Analysis

Intent-to-treat analyses with the last data-point carried forward to account for missing data are reported for the sample of N = 22 and we report effect sizes rather than statistically significant changes. We report assessment dropout that occurred at each outcome assessment and treatment dropout that occurred during FBTY. Participants may have dropped out of treatment but continued to participate in outcome assessments. R version 3.3.219 was used for the linear growth modeling reported in the Appendix.

Results

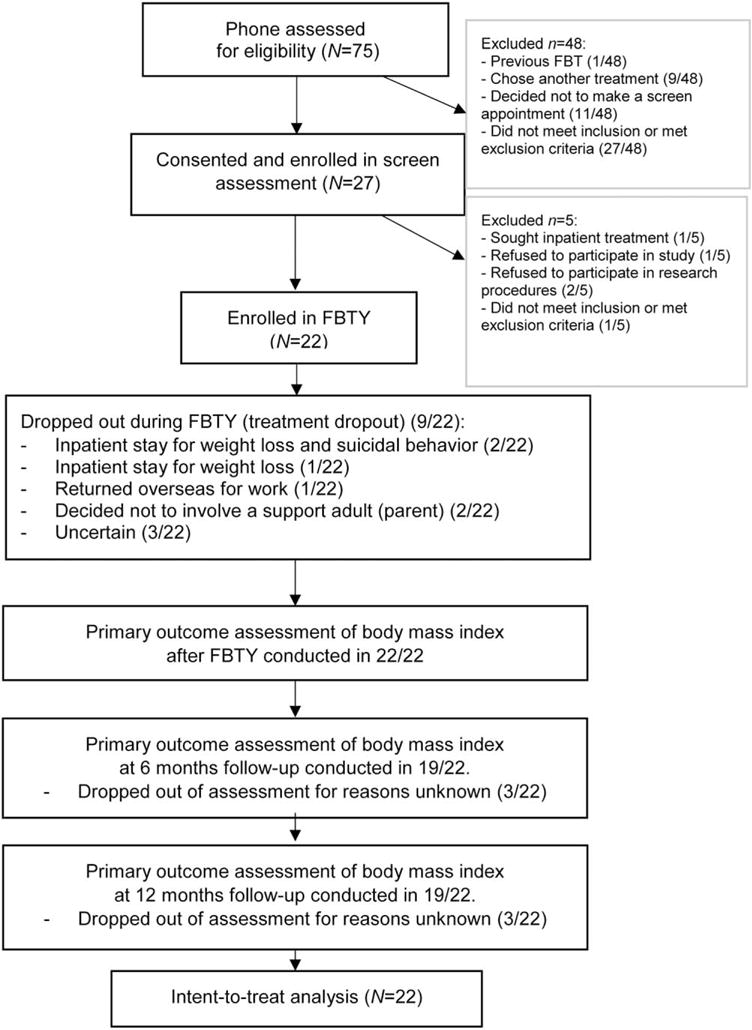

Our first prediction was that FBTY would be accepted by young adult participants and their support adults. After 75 phone screens for this study, 27 participants and their support adults were consented and interviewed in-person and 22 participants and their support adults were enrolled. See Fig. 1 for the consort flow diagram. During treatment, 9/22 (41%) dropped out for a range of reasons, see Fig. 1. During FBTY, 3/22, used higher level treatment and 8/22 used psychotropics. Participants underwent 2–20 FBTY sessions (M = 12, SD = 6) over 2–31 therapy weeks (M = 17, SD = 8). With regards to suitability or acceptability ratings, participants and support adults rated FBTY as more than moderately but less than completely suitable, see Table 1. Table 1 also details retention rates at each outcome assessment.

FIGURE 1.

Consort flow diagram of an open trial of FBT for young adults with AN.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics and effect sizes for primary and secondary outcomes in 22 young adults with subthreshold or threshold AN enrolled in FBT for young adults (FBTY)

| Baseline

|

After FBTY

|

6 Months follow-up

|

12 Months follow-up

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | m (sd) (n = 22) | n | m (sd) | g | 95th Cl | n | m (sd) | g | 95th Cl | n | m (sd) | g | 95th Cl |

| BMI | 17.84 (1.49) | 22 | 19.76 (1.65) | 1.20 | [0.55, 1.85] | 19 | 19.49 (1.87) | 0.95 | [0.30,1.60] | 19 | 19.28 (1.49) | 0.95 | [0.30,1.60] |

| EDE total | 3.13 (1.44) | 20 | 1.41 (1.57) | 1.14 | [0.47, 1.81] | 18 | 1.59 (1.64) | 1.00 | [0.31,1.68] | 18 | 1.73 (1.74) | 0.88 | [0.17,1.59] |

| YBCEDS | 13.82 (8.10) | 19 | 9.32 (8.09) | 0.56 | [−3.03,4.15] | 19 | 6.32 (8.53) | 0.90 | [−2.78, 4.59] | 19 | 7.45 (9.41) | 0.73 | [−3.15,4.61] |

| Axis I disorders | 2(5) | 19 | 0(5) | — | — | 19 | 0(5) | — | — | 19 | 0(5) | — | — |

| GAF | 51.32 (8.74) | 19 | 58.45 (12.83) | 0.66 | [−4.16, 5.48] | 19 | 61.41 (13.88) | 0.88 | [−4.21, 5.97] | 19 | 62.14 (13.85) | 0.94 | [−4.13, 6.02] |

| FBTY suitability: participant | 7.90 (2.38) | 19 | 7.90 (2.79) | — | — | 19 | 8.10 (2.83) | — | — | 19 | 8.10(2.83) | — | — |

| FBTY suitability: support adult | 8.85 (1.93) | 19 | 8.85(2.13) | — | — | 19 | 8.85 (2.13) | — | — | 19 | 8.85(2.13) | — | — |

Notes: g = Hedges g = (m1 − m2)/s* where m1 = baseline mean m2 = mean at second time point. Intent-to-treat analyses with the last data-point carried forward to account for missing data are reported.

95th Cl = 95th percentile confidence interval. Upper and lower limits of the 95th Cl = (Hedges g +/− w) where w = SE × t(n − 1), C; SE = s*/√n; SE = standard error; n = sample size; The t-value for (N−1) was 2.0796 where N = 22. BMI: body mass index; EDE: Eating Disorders Examination-16.21

YBCEDS: Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scale.22

Axis I disorders = assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV: Axis I Disorders16 and the Longitudinal Interview Follow-up Evaluation-Psychiatric Status Ratings17 reporting medians and (range). GAF: global assessment of functioning score.11

FBTY suitability assessed by scales ranging from 0 to 10 where 0 = “not at all,” 5 = “moderately,” and 10 = “completely” in response to: How suitable do you think this treatment is for your problem (or for your family or member or friend)?

The mean age of the sample was 21 years (SD = 2.70; range 18–26 years). The majority of participants were women (20/22) and all reported being single. The majority were Caucasian (18/22), 3/22 were Asian, and 1/22 reported belonging to a racial group “other” than these or African-American, American-Indian or Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander groups. Of the sample, 2/22 reported Hispanic ethnicity. The majority were college students (17/22), 2/22 were unemployed, 1/22 reported being employed in professional or technical jobs and 1/22 in sales jobs, and 1/22 reported their current employment as being “other.” The mean gross annual income reported by young adult participants was $5,394 (SD = $1,720). Applying the ICD-10 criteria,13 10/22 would have met full AN criteria, while 12/22 would have met the atypical AN ICD-1013 criteria. AN duration was 1–10 years and 7/22 had a history of inpatient stays for AN. Of the 22, 16 had co-occurring Axis I disorders: 13 with current mood disorders, 13 with current anxiety disorders, and five with current alcohol and drug abuse disorders. In addition, 6/22 reported histories of suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury.

Seventeen participants were college students and eight were required to leave college because of low weight and were mandated to return only after having sought treatment and gained weight. Initially, 13 lived with biological family members, four with room-mates, and one self-identified as single but cohabiting with a partner. Seven participants returned to live with a family member during treatment. Fourteen participants nominated their biological parents as their support adult; two nominated a friend; one participant, a sibling; one participant, both a partner and a parent; one participant, a sibling and a parent; and three participants were unable to identify a support adult at enrollment, however reported they would be able to nominate a support adult within the first couple of sessions. One of those participants was able to identify a support adult, and two did not nominate a support adult. Given that the biological parents were involved in the initial referral, we anticipated these two participants would choose their biological parents.

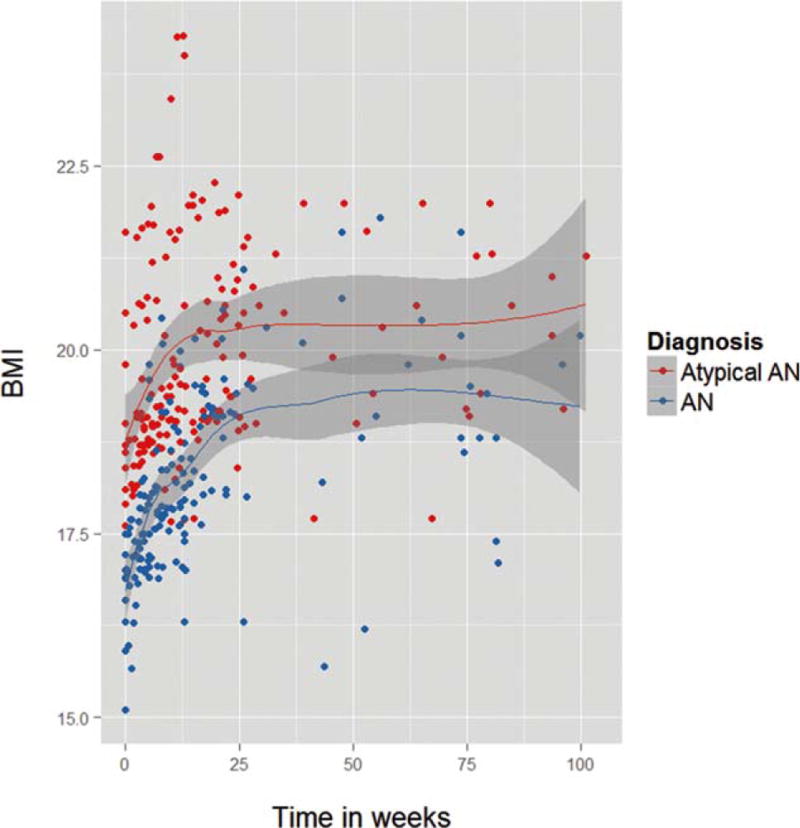

Our second prediction was that FBTY would lead to BMI increases throughout the course of treatment and that the BMI gains would be sustained at 6 and 12 month follow-up visits. Figure 2 shows the BMI trajectory of participants from baseline through the 12 month follow-up visit, grouped by AN and atypical AN diagnostic status. Although 4/22 participants were not underweight and were minimally normal-weight where BMI ≥ 19 kg/m2,20 at baseline, by the end of treatment and six months follow-up, 15/22 were in this range and at the 12 months follow-up, 13/22 were in this range. BMI effect size changes from baseline to the end of treatment and from baseline to each follow-up visit were large, see Table 1. Excluding the two participants who did not have support adults during their time in treatment because of concerns that there was an absence of treatment exposure and rerunning these analyses did not alter the effect sizes.

FIGURE 2.

Weight restoration at baseline, during and after FBT for young adults with Typical and atypical AN. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Our third prediction was that FBTY would reduce eating disorder psychopathology, eating-related obsessions and compulsions, other Axis I disorders, and improve global functioning,21 see Table 1. Using an EDE total score clinical cut-off of 1.47, 1 SD below the mean of an AN sample,11,22 4/22 were outside the AN cut-off at baseline, 13/22 after FBTY, 11/22 at six months follow-up, and 10/22 at 12 months follow-up visits. Eating-related obsessions and compulsions, global functioning, and number of Axis I disorders improved after FBTY. The effect sizes for the improvement in eating-related obsessions and compulsions and global functioning were modest at the end of treatment but increased at follow-up.

Discussion

Although FBT was originally designed for adolescents with AN, the current adaptation of this treatment for young adults with their support adults of choice was reported to be acceptable. FBTY for young adults appeared to have strong effects on weight restoration and global eating disorder signs and symptoms that were maintained through 12 months of follow-up. FBTY also yielded modest improvements in eating-related obsessions and compulsions, number of Axis I disorders, and global functioning.

Nine of the 22 participants dropped out of FBTY and although high, this rate was comparable to those found in other adult AN studies.1 Participants dropped out during FBTY if they did not restore weight quickly, were suicidal, had co-occurring disorders, or did not involve a support adult. However, only 3/22 dropped out of the primary outcome assessments after treatment and we observed improvement, regardless of baseline severity. Of the 19/22 assessed after FBTY, both participants and their support adults rated FBTY as suitable. Uptake of offered therapy sessions was low so even though 18 to 20 sessions were offered, on average 12 sessions were used. It appears FBTY, like other psychotherapies, is not appropriate for every client. Future studies might assess predictors of treatment dropout in FBTY for young adults.

Findings from our proof of concept study demonstrate that family treatment for adolescents can be successfully translated to treat young adults with AN. FBTY appeared helpful for individuals with AN across a range of BMIs. We expected more young adults to choose friends, room-mates, or dormitory mates but were surprised to find that despite not requiring adult consent, the majority of young adult participants chose their parents for support. The success of a family-based treatment with young adults with an ego-syntonic disorder highlights the importance of family support, even in adult treatment.

Generalizability of our findings is limited by the sample size, the lack of sample diversity, and the uncontrolled open trial design. For participants in FBTY, clearly defining how the support adult might be “emotionally invested” in the participant may have made selecting a support adult easier. Finally, it would have been helpful to quantify the number of participants who received individual sessions in the final phase of FBTY and the mean number of individual therapy sessions received.

This study successfully translated a family-based treatment, efficacious for adolescents with AN, to young adults with AN. FBTY resulted in sustained weight restoration and may be a promising treatment for young adults with AN who have a support adult willing to participate in their treatment. Adults with AN suffer from a disorder, which has no known cure. The ultimate goal of this work is to develop a novel and more effective interventions to enhance care or early intervention for young adults with AN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by 1R34MH083914-01A2.

Thank you to the study participants, to the staff funded on the study; and the graduate level trainee assessors.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Watson HJ, Bulik CM. Update on the treatment of anorexia nervosa: Review of clinical trials, practice guidelines and emerging interventions. Psychol Med. 2013;43:2477–2500. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002620. Epub 2012/12/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell K, Peebles R. Eating disorders in children and adolescents: State of the art review. Pediatrics. 2014;134:582–592. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0194.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Grange D, Lock J, Accurso EC, Agras WS, Darcy A, Forsberg S, et al. Relapse from remission at two-to four-year follow-up in two treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:1162–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lock J. An update on evidence-based psychosocial treatments for eating disorders in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44:707–721. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.971458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couturier J, Kimber M, Szatmari P. Efficacy of family-based treatment for adolescents with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:3–11. doi: 10.1002/eat.22042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agras WS, Lock J, Brandt H, Bryson SW, Dodge E, Halmi KA, et al. Comparison of 2 family therapies for adolescent anorexia nervosa: A randomized parallel trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1279–1286. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lock J, le Grange D, Agras WS, Dare C. Treatment Manual for Anorexia Nervosa: A Family-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. New edition. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutmann MP, Pullum-Pinon SM, Pullum TW. Three eras of young adults home leaving in twentieth-century America. J Soc History. 2002;35:533–576. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furstenberg FF, Kennedy S, Mcloyd VC, Rumbaut RG, Settersten RA. Growing up is harder to do. Contexts. 2004;3 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimitropoulos G, Freeman VE, Allemang B, Couturier J, McVey G, Lock J, et al. Family-based treatment with transition age youth with anorexia nervosa: A qualitative summary of application in clinical practice. J Eat Disord. 2015;3:1. doi: 10.1186/s40337-015-0037-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen E, le Grange D, Doyle A, Zaitsoff S, Doyle P, Roehrig J, et al. A case series of family-based therapy for weight restoration in young adults with anorexia nervosa. J Contemp Psychother. 2010;40:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s10879-010-9146-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization (WHO) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairburn CG. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazure MC, Halmi KA, Sunday SR, Romano SJ, Einhorn AM. Yale-Brown-Cornell eating disorder scale: Development, use, reliability, and validity. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:425–445. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.First MB, Gibbon M. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) In: Hilsenroth MJ, Segal DL, editors. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, et al. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieger E, Touyz S, Schotte D, Beumont P, Russell J, Clarke S, et al. Development of an instrument to assess readiness to recover in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:387–396. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200012)28:4<387::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization (WHO) Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.