Abstract

Circulating tumor-derived exosomes (TEX) interact with a variety of cells in cancer-bearing hosts, leading to cellular reprogramming which promotes disease progression. To study TEX effects on the development of solid tumors, immunosuppressive exosomes carrying PD-L1 and FasL were isolated from supernatants of murine or human HNSCC cell lines. TEX were delivered (IV) to immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice bearing premalignant oral/esophageal lesions induced by the carcinogen, 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4NQO). Progression of the premalignant oropharyngeal lesions to malignant tumors was monitored. A single TEX injection increased the number of developing tumors (6.2 versus 3.2 in control mice injected with phosphate-buffered saline; P < 0.0002) and overall tumor burden per mouse (P < 0.037). The numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes infiltrating the developing tumors were coordinately reduced (P < 0.01) in mice injected with SCCVII-derived TEX relative to controls. Notably, TEX isolated from mouse or human tumors had similar effects on tumor development and immune cells. A single IV injection of TEX was sufficient to condition mice harboring premalignant OSCC lesions for accelerated tumor progression in concert with reduced immune cell migration to the tumor.

Tumor-derived exosomes (TEX) were injected IV to immunocompetent mice with the carcinogen 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide–induced premalignant oral squamous cell carcinoma lesions. TEX promoted tumor development, reduced T-cell migration to the tumor and enhanced carcinogenesis by suppressing immune cell migration to the tumor.

Introduction

Head and neck cancers (HNC), including oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC), commonly present with a state of profound immunosuppression, characterized by low lymphocyte counts, impaired T-cell and NK-cell activity, a propensity for T cell apoptosis, and poor antigen presenting function (1–3). The degree of immunosuppression in OSCC is prognostic of poor clinical outcome and accelerated disease progression (4). Current immunotherapeutic approaches for patients with HNCs include strategies for reversing immune cell dysfunction and enabling a revitalization and/or maintenance of immune-mediated anti-tumor activity (5). For instance, the anti-tumor efficacy of immune-based therapies, such as cetuximab (anti-EGFR) and immune check point inhibitors (ICIs; including Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab) are being evaluated alone or in combination with conventional therapies in patients with advanced-stage or recurrent HNC (6,7). To date, the clinical efficacy of these approaches remains limited to a minor subset of patients, with response rates <20% (7). The reasons for such low overall response rates are not known, but one limitation may relate to a common observation of immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment (TME). To develop interventional approaches to counteract such immune deviation, it will first be necessary to understand dominant mechanisms tumors use to undermine protective/therapeutic immunity in vivo.

Known mechanisms of tumor-induced immune suppression are numerous and varied, as recently reviewed (8). Among these, emerging key players regulating anti-tumor immunity are extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are abundantly produced by most tumor cells and can be detected in all body fluids of cancer patients (9,10). Exosomes represent a subset of EVs with an approximate size range of 30–150 nm in diameter that originate from the endocytic compartment of parental (tumor) cells (10). Tumor-derived exosomes (TEX) represent a considerable proportion of total exosomes recovered from plasma of cancer patients, especially those with advanced-stage malignancies. The molecular/genetic profiles of TEX approximate those of their source cells and contain a variety of immunosuppressive ligands, mRNAs and microRNAs (10,11). Once released into the extracellular milieu, TEX are bound and taken up by a broad range of cell types, including stromal cells and immune cells, leading to the molecular reprogramming of the TME toward a pro-tumor and pro-metastatic conditions (12).

Although the role of exosomes in cancer progression has been evaluated in several animal models of cancer to date, in vivo effects of TEX on the development and progression of OSCC have not been investigated (13,14). To do so, we employed a 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4NQO) carcinogen-induced orthotopic model of OSCC in C57BL/6 mice to study the modulatory impact of systemically delivered TEX on pre-malignant to malignant transformation of the oral epithelium in vivo. 4NQO is known to impose intracellular oxidative stress, which causes mutations and DNA strand breaks resulting in transformation of the murine oral epithelium first into pre-cancerous and then cancerous lesions in the tongue and oral mucosa (15). The progressive appearance of these lesions, which are histologically identical to human OSCC lesions provides a highly adventitious model for the mechanistic investigation of step-wise oral carcinogenesis in vivo (15–17).

In this study, we show that a single IV administration of murine or human TEX to 4NQO-conditioned mice with pre-malignant oral lesions facilitates disease progression from a pre-malignant epithelial to a malignant mesenchymal phenotype, induces systemic immune suppression and reduces lymphocytic infiltrates in the developing tumors.

Materials and methods

4NQO oral carcinogenesis model

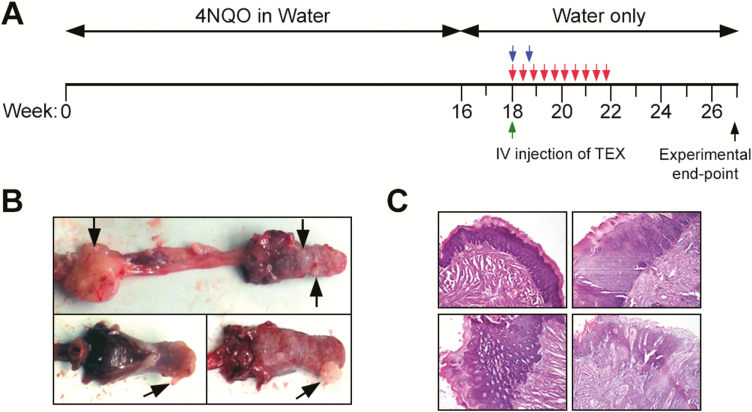

To establish the 4NQO model, female C57BL/6 mice (n = 66) aged 6–8 weeks were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Protocols for animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) under the reference #16088780. To induce the development of oral carcinomas, mice were administered 4-NQO (Sigma–Aldrich) in drinking water at 100 μg/ml for 16 weeks (Figure 1A). Thereafter, normal drinking water was provided. During this period, tumor incidence was 100%. Mice were randomly divided into experimental groups which are listed in Table I. Different doses of exosomes isolated from supernatants of the SCCVII cell line were delivered as a single IV injection via the tail vein (or in another cohort of mice via the orbital route, as indicated in Table I) to groups of mice. The highest injected dose was 90 µg protein which approximately equals 1.125 × 1011 particles. Additionally, exosomes isolated from supernatants of a human OSCC cell line (SCC90) were injected intravenously to groups of mice. The control groups received equivalent volumes of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mice were monitored 2–3 times/week starting with the initiation of 4-NQO treatment for the weight loss or signs of reduced/altered behavior. The mice were euthanized upon 20% weight loss or at 27 weeks after the initial administration of 4-NQO. Tumor size and volume were measured by caliper. Volumetric caliper readings were cross validated with different formulas and most aligned with the volume of an ellipsoid: 4/3π(d1/2 × d2/2 × d3/2). Oropharyngeal tumors were dissected, placed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 1 h and subsequently in 30% sucrose (Sigma–Aldrich) for 24 h. Samples were embedded in the OCT compound (Fisher Scientific) and stored at −80°C for sectioning.

Figure 1.

Treatment schema. (A) A schema is provided for 4NQO oral administration in water for tumor initiation and for IV delivery of TEX beginning in week 18. Green, blue and red arrows indicate IV treatments with TEX. A detailed description of the individual treatments can be found in Table I. (B) Representative images of sublingual, lingual and esophageal tumors on gross observation, harvested at weeks 24–26. Black arrows indicate tumors. (C) Representative tumor and EMT images based on H&E histology.

Table I.

Experimental groupsa

| Group name | Group size | Time of injection | Frequency | Total volume | Injection site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS control | n = 17 | 18 weeks | Once | 100 µl | Tail vein |

| 10× 5 µg SCCVII | n = 4 | 18 weeks | Every 3 days starting at 18 weeks for 10 doses | 100 µl/injection | Tail vein |

| 1× 50 µg SCCVII | n = 4 | 18 weeks | Once | 100 µl | Tail vein |

| 1× 70 µg SCCVII | n = 8 | 18 weeks | Once | 100 µl | Retroorbital |

| 2× 70 µg SCCVII | n = 9 | 18 weeks | Every 5 days starting at 18 weeks for 2 doses | 100 µl/injection | Retroorbital |

| 1× 90 µg SCCVII | n = 8 | 18 weeks | Once | 100 µl | Tail vein |

| 1× 90 µg SCC90 | n = 8 | 18 weeks | Once | 100 µl | Tail vein |

| 1× 90 µg PCI-13 | n = 8 | 18 weeks | Once | 100 µl | Tail vein |

aExperimental groups of this study. 100 µl injections were done after 18 weeks of 4NQO-treatment in all group.

Cell lines

Murine HNSCC cell line SCCVII and human HPV(+) HNSCC line SCC90 were obtained from Dr. Robert L. Ferris, UPMC Hillman Cancer Center, and Dr. Thomas Carey, University of Michigan, respectively. Human HPV(−) HNSCC line PCI-13 was established and maintained in our laboratory. SCCVII and PCI-13 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Lonza, Inc., Williamsport, PA). SCC90 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium. All media were supplemented with 10% (v/v) exosome-depleted and heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and 100 U/ml penicillin with 100 µg/ml streptomycin. All cell lines were authenticated prior to their use and tested for mycoplasma contamination every 3 months. Cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% atmospheric CO2.

Exosome isolation

Exosomes were isolated from freshly harvested cell supernatants as described previously (18). Briefly, each supernatant was centrifuged at room temperature (RT) for 10 min at 2000g and then at 4°C for 30 min at 10 000g followed by ultrafiltration using a 0.22 µm filter (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Aliquots of the supernatants (50 ml) were concentrated to 1 ml using Vivacell 100 concentrators (100 000 MWCO, Sartorius, Stonehouse, UK) at 2000g. Next, 1 ml of each supernatant was placed on 1.5 cm × 12 cm mini-column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA; Econo-Pac columns) packed with Sepharose 2B (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as described previously (14). Exosomes, were eluted with 20 ml of PBS, and individual 1 ml fractions were collected. The bulk of TEX was collected in fraction 4 (18). Protein concentrations were measured using a BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). To concentrate isolated TEX, 0.5 ml aliquots were centrifuged at 5000 g using 100K Amicon ultracentrifugal filters (EMD Millipore).

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed as described previously at the Center for Biologic Imaging at the University of Pittsburgh (19). Briefly, freshly isolated TEX were placed on a copper grid coated with 0.125% Formvar in chloroform and stained with 1% (v/v) uranyl acetate in ddH2O. Exosomes were visualized by the transmission electron microscope JEOL JEM-1011.

Tunable resistive pulse sensing

Size ranges and concentrations of particles in the isolated exosome fractions were measured using tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS) as recommended by the system manufacturer, Izon (Cambridge, MA). All samples were measured under the following conditions: NP#150, A44212, stretch 44.24 mm, voltage 0.62 V and two pressure steps 8–12 mbar. The particle calibration (Part#: CPC200, mean diameter: 200 nm, dilution: 1:1000) was measured directly before and after the experimental sample under identical conditions. Data recording and analysis were performed using the Izon software (version 3.3).

Western blot analysis

Isolated exosomes were tested for the presence of TSG101, an endosomal marker, and other protein markers of interest using western blots as described previously (20). Briefly, 10 μg of exosome protein was lysed with Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), subjected to 15% SDS/PAGE gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) for western blot analysis. Membranes were blocked in 5% fat-free milk in TBST (0.05% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline) for 1h at RT and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies: anti-CD39 (A-16), anti-CD73 (H-300) and COX-2 (1745) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); anti-PD-L1 (ab58810), anti-FasL (ab30871) and anti-Tsg101 (1:1,000, ab30871) from Abcam, Cambridge, MA. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000, Pierce, Thermo-Fisher) was added for 1 h at RT and blots were developed with ECL detection reagents (GE Healthcare Biosciences).

Isolation of splenocytes

Spleens were harvested from healthy control C57BL/6J mice and placed in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% (v/v) exosome-depleted and heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Single-cell suspensions were prepared by mechanically pressing the cells through a 70 μm cell-strainer with a pipet tip. Red blood cells were lysed using RBC lysis buffer (Life Sciences, Carlsbad, CA), washed twice with PBS and immediately used for assays.

Splenocyte flow cytometry

Splenocytes were stained with the following directly-labeled antibodies: CD3 (#553061), CD4 (#552775) and CD8a (#553035), Gr-1 (#553126), CD11b (#557397), FoxP3 (#563101); all purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Cells were incubated for 15 min at RT in the dark, washed 2× with PBS per the manufacturer’s instructions. The data were acquired on a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) and analyzed using the Kaluza software 3.0.

CFSE-based proliferation assay

Splenocytes (5 × 106) from naïve wild-type C57BL/6 mice were washed 1× with PBS (Sigma, Germany), labeled with 2 µM Vybrant® CFDA SE Cell Tracer (CFSE) (Molecular Probes) as described previously (21). CFSE-labeled splenocytes (3 × 105 cells/well) were aliquoted into wells of a 96-well round bottom plate in duplicate. Cells were stimulated ±2.5 µg/ml of concanavalin-A (Sigma) and treated with PBS or TEX (17 µg/well). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and harvested after 48, 72, and 96 h. After harvesting, cells were treated with Fc block (purified rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32) (BD Pharmingen) for 20 min at 4°C and stained with PE-labeled rat anti-mouse CD4 (clone: GK1.5) (BD Pharmingen) and APC-labeled rat anti-mouse CD8a (clone: 53–6.7) (eBioscience) Abs for 30 min at 4°C. Following antibody staining, cells were fixed with 2% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and analyzed with a BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Bioscience). Flow data were further analyzed using FlowJo v.7.6.5. and FlowJo’s proliferation tool was used to assess cell proliferation and to derive cellular generations.

Apoptosis assays

Splenocyte apoptosis was measured using Annexin V Apoptosis Detection kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, the cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in binding buffer, and a 5 μl aliquot of Annexin V-FITC was added to 100 µl of the cell suspension. Cells were incubated for 10 min in the dark at RT, washed with buffer and resuspended in 200 µl of buffer. An aliquot (5 μl) of PI staining solution was added, and cells were analyzed within 4h by flow cytometry using BC Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN). At least 20 000 events per sample were acquired and analyzed using the Kaluza software 3.0 (Beckman Coulter).

Tissue staining

One tumor per mouse was selected for microscopic evaluation. After sucrose exchange and cryopreservation, 6 μm cryostat sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Immunofluorescence was performed on additional sections using rat anti-mouse Ki-67 Abs (1:1000, Invitrogen), rat anti-mouse CD4 antibody (1:100, BD Biosciences), rat anti-mouse CD8a antibody (1:50, BD Biosciences) with overnight incubation at 4°C. Tissue sections were then incubated with donkey anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 Ab (1:500, Invitrogen) for 1 h at RT. Negative controls were stained in parallel with the secondary Abs alone. Sections were counterstained with Hoechst nuclear stain and examined in an Olympus BX51 microscope. Sections were examined blinded by quantifying green fluorescence in three random regions of interest inside the tumor tissue with ImageJ. Data are expressed as the percentage of the area that was positively stained for the region of interest (% of ROI).

Statistical analysis

Significance was determined using the one-way analysis of variance, followed by the post hoc Tukey’s test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7, GraphPad Software). Scatter plots are means ± SEM. When data are presented as box plots, the bar indicates the median, the box shows the interquartile range (25–75%) and the whiskers extend to 1.5 the interquartile range. The P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

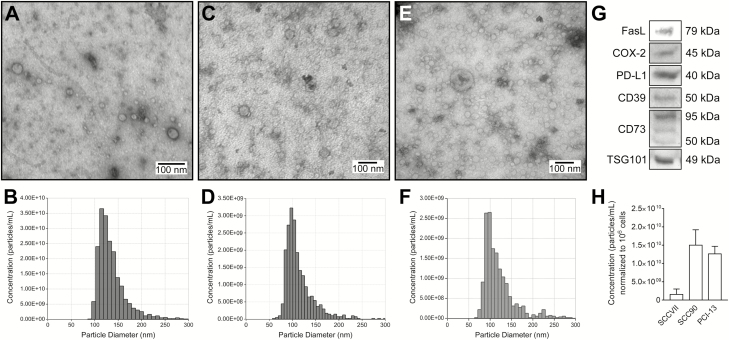

Characterization of HNSCC cell line-derived exosomes

Exosomes (TEX) derived from supernatants of human HNSCC lines have been previously isolated and characterized in our laboratory (18,22,23). Murine exosomes isolated from supernatants of SCCVII cells or human exosomes isolated from supernatants of SCC90 cells by miniSEC were harvested (fraction 4) and evaluated for protein contents and particle numbers (Figure 2). The SCCVII cell line produced exosomes at the average rate of 1.25 × 109 particles/1 μg protein, ranging from 5.2 to 26 × 108 particles/106 cells cultured for 48 h. SCCVII cells produced 10–100 times fewer exosomes than the human HNSCC cell line (Figure 2). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of these exosomes revealed heterogeneous populations of vesicles with an average diameter ranging from 30 to >100 nm (Figure 2A and D). Using TRPS, the vesicle size averaged 123 nm (range 118–128 nm) (Figure 2B). The difference between TEM and TRPS measurements is due to the size of the pore in qNano, which excludes vesicles smaller than 50 nm. Integrating the TME and TRPS results, the size distribution of SCCVII exosomes ranged from 30 to 150 nm (Figure 2D and E). Western blot analysis of SCCVII-derived exosomes indicated that similar to human TEX, these mouse TEX carried a cargo of immunosuppressive proteins, including FasL, PD-L1, CD39, CD73 and a truncated form of COX-2 (Figure 2C) (22).

Figure 2.

Characterization of exosomes derived from mouse SCCVII cells or human SCC90 and PCI-13 HNSCC cell lines. (A) Representative TEM images of SCC90-derived exosomes. (B) Representative TRPS (qNano) size and a concentration distribution plot of SCC90-derived exosomes. (C) Representative TEM images of PCI-13-derived exosomes. (D) Representative TRPS (qNano) size and a concentration distribution plot of PCI-13-derived exosomes. (E) Representative transmission electron microscope images of SCCVII-derived exosomes. (F) Representative TRPS (qNano) size and a concentration distribution plot of SCCVII-derived exosomes. (G) Western blot (WB) profiles of immunoregulatory proteins carried by SCCVII-derived exosomes. Each lane was loaded with 10 μg protein of exosomes lysate. TSG101 is an ESCRT-1 complex protein confirming the endosomal origin of exosomes. (H) Particle concentrations in fraction 4 samples of exosomes derived from SCCVII, PCI-13 or SCC90 cells and normalized to 106 of exosome-producer cells.

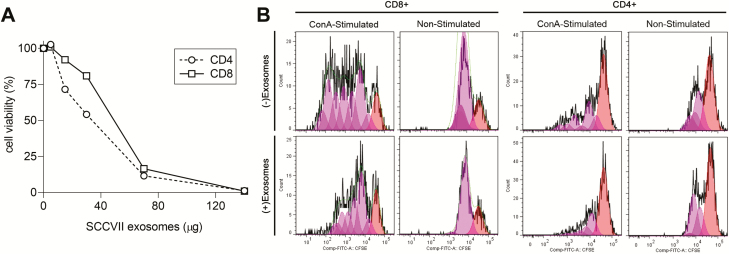

SCCVII-derived exosomes are immunosuppressive in vitro

SCCVII-derived exosomes suppressed proliferation and induced apoptosis of murine T lymphocytes in vitro, although to a lesser degree than was observed for human TEX (22). Specifically, when coincubated with freshly harvested normal splenocytes activated with anti-CD3/28 Abs and IL-2, murine TEX induced lymphocyte apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A). SCCVII-derived exosomes also inhibited proliferation (P < 0.05) of both CD4+ and CD8+ T splenocytes (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

SCCVII-derived TEX-induced apoptosis (A) and proliferation inhibition (B) of CD4+ or CD8+ splenocytes in vitro. (A) Apoptosis of normal C57BL/B mouse splenocytes 24 h after incubation with increasing concentrations (in μg) of SCCVII-derived TEX. Cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V and were assessed by flow cytometry. (B) Proliferation as measured by CFSE uptake by Con A-activated versus resting CD4+ and CD8+ splenocytes coincubated with/without SCCVII-derived TEX on day 3 of culture. Data are from a representative experiment of three performed.

In vivo impact of TEX delivered IV during carcinogen-induced HNSCC development

To evaluate the impact of systemically delivered TEX on HNSCC carcinogenesis, C57BL/6 mice were administered 4NQO via drinking water for 16 weeks, at which time oral pre-cancerous lesions were detected by visual inspection. After randomizing the animals into cohorts of equivalent size, the mice were treated by IV injection (either via tail vein or retro-orbital vein) with PBS (negative control), SCCVII-derived TEX, PCI-13-derived TEX or SCC90-derived TEX as described in Table I beginning in week 18.

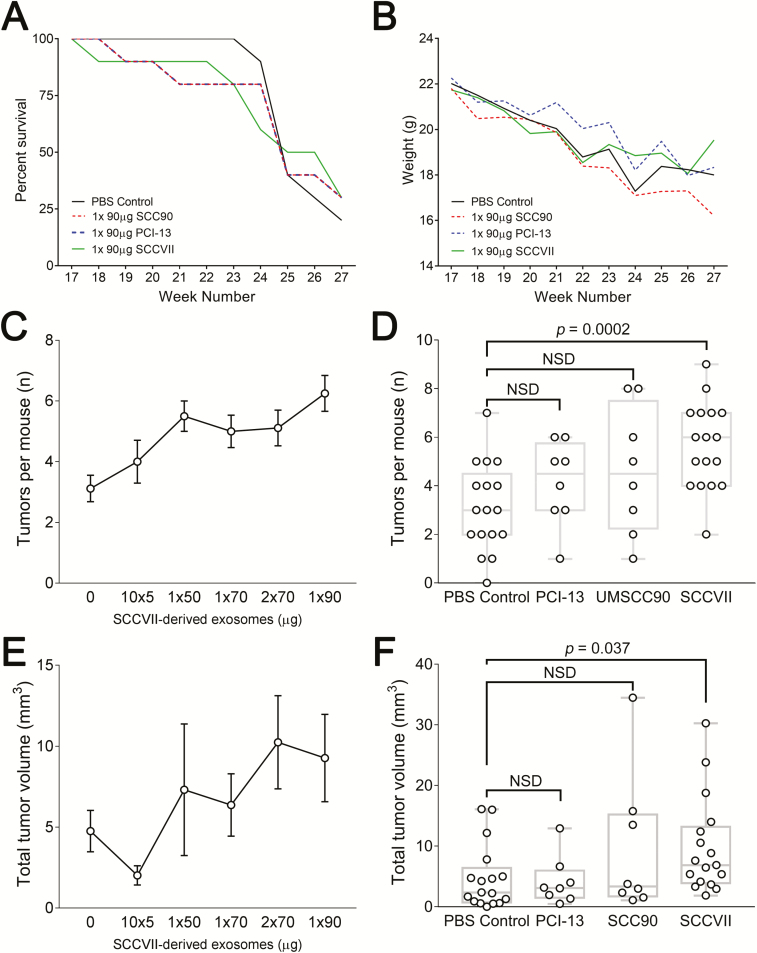

We observed no differences between PBS- or TEX-treated animals with regard to weight loss or overall survival over time on trial (Figure 4). Weight loss was greatest during weeks 23–25 across all groups (Figure 4B), and the mean time to death (or euthanasia) was between 26 and 27 weeks (Figure 4A). However, gross tissue examination under ×3 optical magnification of the oropharyngeal and esophageal tract of each mouse revealed an increased number of tumors when 90 µg SCCVII-derived TEX protein (estimated 1.13 × 1011 particles) was delivered as a single IV injection on week 18 (Figure 4C). Upon sacrifice on week 28, an average of 6.2 tumors were observed in these mice, while PBS-treated control mice had a mean of 3.2 tumors (P < 0.0002; Figure 4D). Injection of lower doses of TEX or split-dosing of TEX over time (e.g. 10 injections of 5 µg protein each, delivered every 3 days (10× 5 µg) or two injections of 70 µg (2× 70 µg) delivered one week apart) did not result in increased numbers of lesions/mouse or aggregate tumor volume (Figure 4), although we did note that the number of tumors appeared to increase in a TEX concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4C). These results suggest that a single high-dose bolus of TEX had a greater impact on disease progression than smaller doses of TEX delivered throughout the pre-cancerous phase of carcinogenesis.

Figure 4.

Mean survival (A) and rates of weight loss (B) for the PBS control group compared with the group receiving 90 μg of exosomes from SCCVII, PCI-13 or SCC90 cells. In C–F, composite in vivo tumor data collected by the gross examination under ×3 magnification of oropharyngeal and esophageal tissue per mouse and reported by group. (C) Average number of tumors per mouse per treatment cohort (receiving different total levels of SCCVII exosomes; in μg protein). (D) Average numbers of tumors per mouse in mice receiving 90 μg or 2× 70 μg of SCCVII-derived TEX, 90 μg SCC90-derived TEX, 90 μg PCI-13-derived TEX or 100 μl PBS as a control. (E) Aggregate volumes of tumors per mouse as measured in groups of mice receiving different total levels of SCCVII-derived exosomes (in μg protein). (F) Aggregate tumor volumes per mouse as measured in groups of mice receiving 90 μg or 2× 70 μg of SCCVII-derived TEX, 90 μg of SCC90-derived TEX, 90 μg PCI-13-derived TEX or 100 μl PBS as control. The tumor volume data in (C and D) are calculated as an ellipsoid (4/3π abc).

In contrast to the SCCVII-derived TEX dose-dependency in lesion number observed, the impact of TEX dosing on composite tumor burden per group (an average total volume of tumors per mouse) was less clear, but with a statistically significant difference in the average tumor volume discerned across the experimental versus control groups (Figure 4E).

Human HNSCC SCC90 and PCI-13 cell line-derived TEX were also tested for their ability to increase tumor lesion numbers or volume in 4NQO-conditioned mice. Although human TEX contained 10- to 100-fold greater number of particles per unit protein than SCCVII-derived TEX, their IV delivery resulted in only moderate increases in numbers of tumors following a single injection when compared with an equivalent 90 µg dose of mouse TEX, and tumor volumes were unaffected versus control PBS-treated mice (Figure 4D and F).

Delivery of TEX leads to reduced infiltration of tumors by T cells

Histological examination of tumor tissue sections harvested nine weeks after TEX delivery (i.e. week 27/28) showed the presence of poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinomas with large, partially pleomorphic and atypical cells and meager keratinization (Figure 1C). H&E staining was similar for all experimental groups. Tumors disrupted the basal layer of the tongue epithelium and infiltrated the neighboring tissue. Immunofluorescence for Ki67 showed tumors with equal proliferation indices across all groups, with the average Ki67+ population representing ~6% of total cells (Figure 5B). Importantly, fewer CD8α + T cells were observed inside the tumors in mice treated with exosomes (SCC90: P = 0.0001; PCI-13: P = 0.004; SCCVII: P = 0.0001; Figure 5D). CD4+ T cells were also significantly decreased in number in the TEX-treated cohorts versus control mice (SCC90: P = 0.007; PCI-13: P = 0.001; SCCVII: P = 0.0003; Figure 5C). Overall, the IV delivery of mouse or human TEX to mice with pre-cancerous tumor lesions resulted in a reduction in lymphocytic infiltrates associated with advanced-stage cancer.

Figure 5.

IFM analysis of the impact of TEX delivery on 4NQO-induced oral carcinoma in mice. (A) Representative IFM staining of tumor sections at week 27/28 from the various indicated treatment cohorts for Ki-67, CD4 and CD8a (green fluorescence) with DAPI counterstaining of nuclei (blue fluorescence) at ×10 magnification (scale bar: 100 μm). Quantitative analysis of IFM staining Ki-67 (B), CD4 (C) and CD8a (D). All data are expressed as the percentage of the area positively stained from the region of interest (% ROI).

Systemic immunomodulatory effects of TEX

At time of sacrifice (week 27/28), splenocytes were harvested from individual 4NQO-treated mouse and cryopreserved for further analysis. Splenocytes were thawed, stained and analyzed for CD4, CD8, Treg (CD4+FoxP3+) and myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC; CD11b+Gr-1+) phenotype by flow cytometry. No major differences in the splenocyte content were noted across any treatment cohorts, with the exception of an observed statistically significant decrease in CD8+ T cells (P = 0.036 versus PBS; Supplementary Figure S3, available at Carcinogenesis Online) and MDSC (P = 0.0175 versus PBS; Supplementary Figure S4C, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Discussion

TEX isolated from supernatants of HNC cell line supernatants or plasma of patients with cancer have been reported to carry a cargo of immunosuppressive proteins that upon coincubation with immune cells can interfere with their protective/therapeutic functions (22,23). TEX coincubated with murine or human tumor cells in vitro promote tumor cell growth (24). In vivo, TEX injected into mice with established tumors have been reported to support enhanced tumor growth and to facilitate tumor metastasis via the induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (25,26). In recent years, it has also been shown that TEX can condition pre-metastatic niches permissive for tumor metastatic seeding and disseminated growth (27,28). TEX are known to functionally reprogram a wide range of recipient cell types. For instance, TEX reprogram endothelial cells to support angiogenesis that fuels tumor growth, while coordinately altering vascular permeability to support tumor metastasis (27,29). TEX also reprogram stromal fibroblasts, converting them into pro-tumorigenic and pro-angiogenic CAFs (30). In addition, TEX suppress immune cell functions to facilitate tumor immune escape and evasion and coordinately promote tumor growth (i.e. pro-angiogenic) and metastasis (27).

While the emerging in vitro and in vivo data support the pleiotropic pro-tumor roles of TEX, the mechanisms underpinning TEX involvement in the process of tumorigenesis remains obscure. We asked whether delivery of exogenous TEX to immunocompetent mice predisposed to develop OSCC impacts subsequent tumor development, while coordinately interfering with host immunity. Taking advantage of the 4NQO carcinogen-induced orthotopic mouse model of HNSCC, where premalignant lesions form by 16 weeks of treatment and then progress to carcinomas over time, similar to human OSCCs, we delivered IV injections of murine or human HNSCC cell line-derived TEX early in the tumor development period, at a pre-malignant stage (15).

Surprisingly, we found that a single IV injection of SCCVII-derived TEX at a dose of 90 µg protein was sufficient to significantly increase the number and total volume of multi-focal oral carcinomas by week 27/28. Repeated delivery of lower TEX doses did not reproduce this carcinogenesis-enhancing effect. While the number of tumors increased, the aggregate volume of tumors increased only moderately, presumably due to the tumor location in the oropharynx and esophagus, the anatomical locations which limited expansion and necessitated the sacrifice of mice based on expanding tumors constricting nutrient uptake. Thus, the observed moderate increase in total tumor burden after TEX delivery is a limitation imposed by the 4NQO model. On the other hand, invasiveness of the tumors into surrounding tissue was significantly increased in mice receiving TEX. Overall, these results suggest that the injected TEX promoted carcinogenesis by enhancing neoplastic transformation followed by the appearance of new tumors rather than by accelerating growth of existing tumors. In vivo, TEX-mediated high-grade transformation of dysplastic lesions into malignant lesions was TEX-dose dependent and was best triggered by a one large TEX dose rather than by repeated delivery of smaller doses of TEX.

Importantly, murine HNSCC-derived TEX had a greater impact on carcinogenesis in this model than did human HNSCC-derived TEX. These results contrast with several reports where human exosomes appeared to retain biologic activity in mice (31). As TEX carry MHC class I and class II antigens, there was a concern that human TEX might be rapidly cleared in mice. However, preliminary data from our collaborators suggest that human cell-line derived exosomes persist in the murine circulation to a similar degree as their murine counterparts (data not shown). Our results (Figure 5) suggest that human TEX persist in the murine circulation and retain tumor promoting functionality, albeit with somewhat limited activity compared with mouse TEX. The potency of human cell line-derived exosomes in vivo might be limited due to (suboptimal) speciation in ligand-receptor interactions rather than by immune recognition and clearance of foreign exosomes. Other studies have hinted on the immune privilege of human exosomes, further supporting their unimpaired cross-species activity in the murine TME (32).

TEX used in our studies carried a cargo of immunosuppressive proteins and their delivery had significant effects on the viability of murine T cells. TEX coincubated with in vitro activated splenocytes, induced apoptosis in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in a dose-dependent manner. Our analysis of tumor tissues at sacrifice (week 28) indicated that TEX delivered IV at the time of pre-neoplastic development had long-lasting effects on immune cells in the TME. In tumors obtained from mice injected with TEX, a significant decrease in immune cell infiltrates was observed relative to tumors in control-treated mice. These data suggest that TEX delivered early in carcinogenesis mediate profound and long-lasting effects on the host immune system, potentially eliminating effector cells responsible for lysis of malignant cells. In addition, our analysis of splenocytes isolated from mice injected with TEX suggest a potential expansion of regulatory cells, Treg and MDSC, in agreement with other reports for TEX induced expansion and functional augmentation of human regulatory cells in vitro or in vivo in mice (33,34).

Remarkably, one large dose of TEX delivered IV to mice with premalignant lesions was more effective in increasing numbers of tumors and potentially also in decreasing CD8+ T cell numbers in the spleen versus multiple injections of smaller doses of TEX. These differences may be explained by timing of the multiple injections between mice groups, where various premalignant lesions are not synchronized in their development stages when the exosomes are injected, or by a calibrated need for a robust reprogramming signal that cannot be replaced by multiple subthreshold signals. It may also be that one strong signal is more effective in inducing immune dysfunction that cannot be recapitulated by more frequent, but weaker TEX signaling.

In summary, the 4NQO model of carcinogenesis in OSCC was useful in illustrating that murine and human TEX can play key roles in chemical carcinogenesis by enforcing cell transformation, modulating tumor progression and reprogramming the protective host immune system. This model provides a new platform for further elucidation of molecular and genetic mechanisms of carcinogenesis that are driven by TEX. Gaining insights into the biologic and molecular mechanisms that underlie TEX reprogramming of the TME including immune suppression in vitro and in vivo provides new opportunities for future translation of selective TEX-depleting strategies as interventional approaches in the clinic as adjuncts to existing immunotherapies (e.g. checkpoint inhibitors or adoptively transferred engineered T cells).

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R0-1 CA168628, R0-1 CA168628 05S1 to T.L.W.); Leopoldina Fellowship from German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina (LPDS 2017-12 to N.L.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Sonja Ludwig for performing the TEM of exosomes obtained from SCC90 cells.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- EV

extracellular vesicles

- HNC

head and neck cancers

- OSCC

oral squamous cell carcinomas

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RT

room temperature

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- TEX

tumor-derived exosomes

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- TRPS

tunable resistive pulse sensing

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

References

- 1. Ferris R.L. (2015) Immunology and immunotherapy of head and neck cancer. J. Clin. Oncol., 33, 3293–3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dasgupta S., et al. (2005) Inhibition of NK cell activity through TGF-beta 1 by down-regulation of NKG2D in a murine model of head and neck cancer. J. Immunol., 175, 5541–5550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferris R.L., et al. (2006) Immune escape associated with functional defects in antigen-processing machinery in head and neck cancer. Clin. Cancer Res., 12, 3890–3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Czystowska M., et al. (2013) The immune signature of CD8(+)CCR7(+) T cells in the peripheral circulation associates with disease recurrence in patients with HNSCC. Clin. Cancer Res., 19, 889–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mooradian M.J., et al. (2017) Immunomodulatory effects of current cancer treatment and the consequences for follow-up immunotherapeutics. Future Oncol., 13, 1649–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jie H.B., et al. (2015) CTLA-4⁺ regulatory T cells increased in cetuximab-treated head and neck cancer patients suppress NK cell cytotoxicity and correlate with poor prognosis. Cancer Res., 75, 2200–2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferris R.L., et al. (2016) Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med., 375, 1856–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whiteside T.L. (2018) Head and neck carcinoma immunotherapy: facts and hopes. Clin. Cancer Res., 24, 6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Whiteside T.L. (2016) Tumor-derived exosomes and their role in cancer progression. Adv. Clin. Chem., 74, 103–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whiteside T.L. (2017) Exosomes carrying immunoinhibitory proteins and their role in cancer. Clin. Exp. Immunol., 189, 259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whiteside T.L. (2017) The effect of tumor-derived exosomes on immune regulation and cancer immunotherapy. Future Oncol., 13, 2583–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whiteside T.L. (2018) Exosome and mesenchymal stem cell cross-talk in the tumor microenvironment. Semin. Immunol., 35, 69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lagerweij T., et al. (2018) A preclinical mouse model of osteosarcoma to define the extracellular vesicle-mediated communication between tumor and mesenchymal stem cells. J Vis Exp., 135, e56932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grange C., et al. (2011) Microvesicles released from human renal cancer stem cells stimulate angiogenesis and formation of lung premetastatic niche. Cancer Res., 71, 5346–5356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang X.H., et al. (2004) Oral cavity and esophageal carcinogenesis modeled in carcinogen-treated mice. Clin. Cancer Res., 10(1 Pt 1), 301–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang Z., et al. (2013) Comparable molecular alterations in 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide-induced oral and esophageal cancer in mice and in human esophageal cancer, associated with poor prognosis of patients. In Vivo, 27, 473–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schoop R.A., et al. (2009) A mouse model for oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Mol. Histol., 40, 177–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hong C.S., et al. (2016) Isolation of biologically active and morphologically intact exosomes from plasma of patients with cancer. J. Extracell. Vesicles, 5, 29289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ludwig N., et al. (2018) Exosomes from HNSCC promote angiogenesis through reprogramming of endothelial cells. Mol. Cancer Res., 16, 1798–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hong C.S., et al. (2017) Circulating exosomes carrying an immunosuppressive cargo interfere with cellular immunotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci. Rep., 7, 14684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quah B.J., et al. (2012) New and improved methods for measuring lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and in vivo using CFSE-like fluorescent dyes. J. Immunol. Methods, 379, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ludwig S., et al. (2018) Molecular and functional profiles of exosomes from HPV(+) and HPV(−) head and neck cancer cell lines. Front. Oncol., 8, 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ludwig S., et al. (2017) Suppression of lymphocyte functions by plasma exosomes correlates with disease activity in patients with head and neck cancer. Clin. Cancer Res., 23, 4843–4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsumoto A., et al. (2017) Accelerated growth of B16BL6 tumor in mice through efficient uptake of their own exosomes by B16BL6 cells. Cancer Sci., 108, 1803–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Costa-Silva B., et al. (2015) Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat. Cell Biol., 17, 816–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kucharzewska P., et al. (2013) Exosomes reflect the hypoxic status of glioma cells and mediate hypoxia-dependent activation of vascular cells during tumor development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 110, 7312–7317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quail D.F., et al. (2013) Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Med., 19, 1423–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peinado H., et al. (2012) Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat. Med., 18, 883–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Skog J., et al. (2008) Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat. Cell Biol., 10, 1470–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Webber J., et al. (2010) Cancer exosomes trigger fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. Cancer Res., 70, 9621–9630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li L., et al. (2018) Microenvironmental oxygen pressure orchestrates an anti- and pro-tumoral gammadelta T cell equilibrium via tumor-derived exosomes. Oncogene., 38, 2830–2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stenqvist A.C., et al. (2013) Exosomes secreted by human placenta carry functional Fas ligand and TRAIL molecules and convey apoptosis in activated immune cells, suggesting exosome-mediated immune privilege of the fetus. J. Immunol., 191, 5515–5523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yamada N., et al. (2016) Colorectal cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles induce phenotypic alteration of T cells into tumor-growth supporting cells with transforming growth factor-β1-mediated suppression. Oncotarget, 7, 27033–27043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wieckowski E.U., et al. (2009) Tumor-derived microvesicles promote regulatory T cell expansion and induce apoptosis in tumor-reactive activated CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol., 183, 3720–3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.