Abstract

Background

MED13L-related intellectual disability is a new syndrome that is characterized by intellectual disability (ID), motor developmental delay, speech impairment, hypotonia and facial dysmorphism. Both the MED13L haploinsufficiency mutation and missense mutation were reported to be causative. It has also been reported that patients carrying missense mutations have more frequent epilepsy and show a more severe phenotype.

Case presentation

We report a child with ID, speech impairment, severe motor developmental delay, facial deformity, hypotonia, muscular atrophy, scoliosis, odontoprisis, abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG), and congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO) combined with high ureter attachment. We used whole-exome sequencing (WES) to detect the genetic aberration of the child and found a de novo mutation, c.2605C > T (p.Pro869Ser), in the MED13L gene. Neither of her parents carried the mutation. Additionally, we review the literature and summarize the phenotypes and features of reported missense mutations. After reviewing the literature, approximately 17 missense mutations in 20 patients have been reported thus far. For 18 patients (including our case) whose clinical manifestations were provided, 100% of the patients had ID or developmental delay (DD). A total of 88.9, 83.3 and 66.7% of the patients had speech impairment, delayed milestones and hypotonia, respectively. A total of 83.3% of the patients exhibited craniofacial deformity or other dysmorphic features. Behavioral difficulties and autistic features were observed in 55.6% of the patients. Cardiac anomalies were seen in only 27.8% of the patients. Of these patients, 44.4% had epileptic seizures. Of the 17 mutations, 2 were located in the N-terminal domain, 8 were located in the C-terminal domain, and 1 was located in an α-helical sequence stretch. One of them was located in the MID domain of the MedPIWI module.

Conclusions

We report a new patient with a reported missense mutation, c.2605C > T (p.Pro869Ser), who exhibited some infrequent manifestations except common phenotypes, which may broaden the known clinical spectrum. Additionally, by reviewing the literature, we also found that patients with missense mutations have a higher incidence of seizures, MRI abnormalities, autistic features and cardiac anomalies. They also have more severe ID and hypotonia. Our case further demonstrates that Pro869Ser is a hotspot mutation of the MED13L gene.

Keywords: MED13L, Missense mutation, Intellectual disability, Speech impairment

Background

Mediator complex subunit 13-like gene (MED13L), which is a component of the Mediator complex in HeLa cells [1], was first linked to intellectual disability (ID) and congenital heart disease (CHD) in 2003 by Muncke et al. [2]. The patient reported by Muncke et al. harbored a translocation disrupting MED13L, and three additional missense mutations in MED13L (p.Glu251Gly, p.Arg1872His, and p.Asp2023Gly) were found by mutation screening of dextro-looped transposition of the great arteries (dTGA) patients. Muncke et al. cloned MED13L using a positional cloning approach, and they designated the gene as PROSIT240 due to the protein similarity to the human thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein 240 [2]. Independently, Musante et al. cloned the gene by RT-PCR and 5-prime RACE of human fetal brain and lymphoblastoid cell line cDNA libraries, which they called THRAP2 [3]. A decade later, an increasing number of cases harboring large intragenic or whole gene deletions/duplications of the MED13L gene, chromosomal translocation disrupting the MED13L gene, de novo frameshift variants, nonsense mutations, and splice site mutations were published, exhibiting moderate ID, severe speech impairment, motor developmental delay, facial deformity and/or CHD, and these were recognized as MED13L haploinsufficiency syndrome [4–11]. Several missense mutations in the MED13L gene have also been reported and are supposed to frequently have a more severe phenotype with hypotonia, more frequently epilepsy, severe absent speech, and severely delayed motor function compared to patients with truncating variants [11–14].

Here, we report another de novo p.Pro869Ser change in the MED13L gene that exhibits ID, speech impairment, severe motor developmental delay, facial deformity, hypotonia, muscular atrophy, hyperlaxity of the joints, scoliosis, odontoprisis, abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG), and congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO) combined with high ureter attachment that has never been reported in MED13L-related syndrome. Our observation of UPJO in this patient further broadens the known clinical spectrum. Additionally, we review the current literature to summarize in detail the missense mutations of the MED13L gene and the clinical characteristics of reported patients with missense mutations of the MED13L gene.

Case presentation and methods

Case presentation

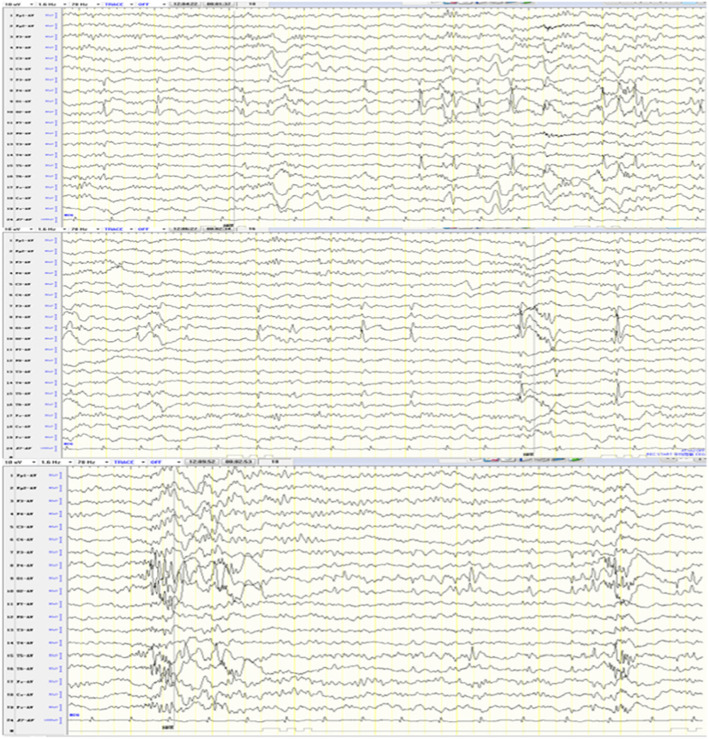

The patient is a girl who was born at term after 38 weeks of pregnancy with a birth weight of 2500 g, without a history of asphyxia at birth. She is one of a fraternal pair of twins as the second pregnancy of healthy, non-consanguineous parents. Her older sister and twin brother are healthy. She is 4 years and 5 months old now, weighs 11 kg (<P3) and is 100 cm tall (between P3 and P10). Her head circumference was 45 cm (<P3). She had hypotonia since birth and presented muscular atrophy of the extremities as well as hyperlaxity of the joints. She had scoliosis and had spontaneous fracture of the distal right femur at 1 year old. Abnormal facial deformity includes frontal bossing, low-set ears, hypertelorism, epicanthus, depressed nasal bridge, bulbous nasal tip, cupid-bow upper lip combined with open mouth appearance and micrognathia (Fig. 1). From 3 years and 4 months old, she had unconscious frequent odontoprisis. Her developmental milestones were severely delayed, as she raised her head at 1 year. At the last evaluation, the girl was 4 years and 5 months old, and she could not yet sit or stand without support, let alone walk. Her speech was also severely delayed; she can speak single words such as “Ma, Pa” with ambiguous pronunciation, and she can understand simple instructions. She also exhibits autistic features. She had no clinically observed seizures but had abnormal EEG showing spike and slow wave colligation and multi-spike and slow waves in the bilateral occipital and posterior temporal regions, as well as rapid rhythm distribution in the occipital area (Fig. 2). Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) at 5 months old showed enlarged bilateral lateral ventricles. Echocardiography found patent ductus arteriosus that was closed at 2 years and 10 months, and mild aortic coarctation, mild aortic regurgitation and slight tricuspid regurgitation appeared. UPJO combined with high ureter attachment of the right was discovered in this girl due to uronephrosis, and she underwent surgery at 6 months old. Now she still has a mild right kidney seeper.

Fig. 1.

Photograph of the patient. The picture shows microcephaly, frontal bossing, low-set ears, hypertelorism, epicanthus, depressed nasal bridge, bulbous nasal tip, cupid-bow upper lip combined with open mouth appearance, micrognathia, muscular atrophy

Fig. 2.

EEG shows spike and slow wave colligation and multi-spike and slow waves in the bilateral occipital and posterior temporal regions, as well as rapid rhythm distribution in the occipital area

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) found a de novo mutation, c.2605C > T (p.Pro869Ser), in the MED13L gene. Neither of her parents had the mutation. The region of the mutation is an important part of the protein, with highly conserved amino acid sequences in different species. This mutation is predicted to be disease causing by Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/) and is predicted to be damaging with a score of 1.000 (sensitivity: 0.00; specificity: 1.00) by Polyphen 2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) and damaging with a score of 0.000 by SIFT (cutoff = 0.05) (http://sift.jcvi.org/www/SIFT_BLink_submit.html).

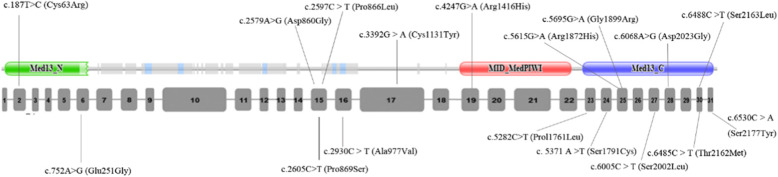

By reviewing the literature, approximately 17 missense mutations in 20 patients have been reported thus far. Together with our case, a total of 21 patients with MEDL13L missense mutations are summarized in Table 1. Among them, 18 patients (including our case) were provided with clinical manifestations. One hundred percent of the patients have ID or DD. A total of 88.9, 83.3 and 66.7% of the patients had speech impairment, delayed milestones and hypotonia, respectively. A total of 83.3% of the patients exhibited craniofacial deformity or other dysmorphic features, and the most common features were low-set ears, hypertelorism, depressed nasal bridge, bulbous nasal tip, cupid-bow upper lip and open mouth appearance. Behavioral difficulties, such as self-harm and autistic features, were seen in 55.6% of the patients. Cardiac anomalies are seen in only 27.8% of the patients, and there is no complex CHD. Of the patients with missense mutations, 44.4% have epileptic seizures, and even one patient with c.2579A > G(Asp860Gly) has intractable seizures. In 12 patients who received MRI examination, 8 (66.7%) had abnormalities, and most of these anomalies were nonspecific. Of the 17 mutations, 2 were located in the N-terminal domain, 8 were located in the C-terminal domain, and 1 was located in an α-helical sequence stretch spanning residues Val858-Met864 [14]. Another mutation, Arg1416His, was located in the MID domain of the MedPIWI module (http://pfam.xfam.org/).

Table 1.

Clinical features of described patients with MED13L missense mutations and in silico-analysis results of these mutations

| Literature | Our case | [2] | [15] | [16] | [17] | [18] | [14] | [19] | [13] | |||

| Mutations | c.2605C > T (Pro869Ser) | c.752A > G (Glu251Gly) | c.5615G > A (Arg1872His) | c.6068A > G (Asp2023Gly) | c.4247G > A (Arg1416His) | c.2579A > G (Asp860Gly) | c. 5371 A > T (Ser1791Cys) | c.5695G > A (Gly1899Arg) | c.2579A > G (Asp860Gly) | c.5282C > T (Prol1761Leu) | c.187 T > C (Cys63Arg) | |

| Inheritance | De novo | maternally inherited | inheritance: NM | inheritance: NM | homozygous | De novo | Paternally inherited | De novo | De novo | NM | De novo | |

| Exon | 15 | 6 | 25 | 28 | 19 | 15 | 24 | 25 | 15 | 23 | 2 | |

| Domain | N-terminal domain | C-terminal domain | C-terminal domain | MID-MedPIWI | α-helical sequence | C-terminal domain | α-helical sequence | C-terminal domain | N-terminal domain | |||

| SIFT | damaging | damaging | tolerated | tolerated | damaging | tolerated | damaging | damaging | tolerated | tolerated | damaging | |

| Polyphen2 | probably damaging | possibly damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | benign | probably damaging | |

| Mutation taster | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | polymorphism | disease causing | |

| mRNA expression levels are significantly decreased revealed by qRT-PCR | ||||||||||||

| ID | + | Except dTGA, there are no other clinical features provided in these three patients | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| Speech impairment | + | NM | NM | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Delayed milestones | + | NM | NM | NM | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Growth parameter | weight | low | NM | NM | NM | low | NM | NM | NM | |||

| height | short | NM | NM | NM | – | NM | NM | NM | ||||

| Head deformities | microcephaly | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | ||||

| Behavioral difficulty/autism | + | NM | NM | + | Autism/auto-aggression |

poor attention span |

anxiety and disruptive and aggressive behavior | Self-harm, autism | ||||

| Hypo- or hyper-tonia | Hypotonia | NM | NM | NM | Hypotonia | Hypotonia | Hypotonia/feeding difficulties | Hypotonia since birth whereas turn hypertonic since 4 y 10 m | ||||

| Craniofacial deformity and other dysmorphic features |

frontal bossing, low-set ears, hypertelorism, epicanthus, depressed nasal bridge, bulbous nasal tip, cupid-bow upper lip combined with open mouth appearance, micrognathia |

NM |

small dysplastic low-set ears, bulbous nasal tip, large mouth, single transverse palmar crease of the right hand |

No dysmorphic features |

asymmetric face, strabismus, left eye ptosis, ocular hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures, bilateral epicanthus, wide, depressed nasal root, tented upper lip with frequent drooling, and low set ears |

squared, low set ears with rather narrow ear lobes, mild ptosis, flat malar region, mild broadening of the nose, retrognathia |

right-sided torticollis, asymmetric facies with simple uncurled slightly low-set right ear that protrudes from the head, enlargement or protrusion of the skull, and two small cafe au lait spots |

reduced palpebral fissures, nasal base enlargement, enlarged plane philtrum, a thin upper lip, low-set ears, and a prominent columella |

||||

| Cardiac anomalies |

mild aortic coarctation, mild aortic regurgitation, slight tricuspid regurgitation |

dTGA | dTGA | dTGA | NI | NM | NM | patent ductus arteriosus | NI | atrial septal defect | NI | |

| Urinary system | Congenital UPJO combined with high ureter attachment of right | NM | NM | NM | NM | NI | NM | NM | ||||

| Miscellaneous | Odontoprisis, appendicular muscular atrophy, hyperlaxity of the joints, scoliosis, spontaneous facture of femur | unilateral hearing loss, atopic dermatitis | With no muscle weakness, but was still clumsy, some hyperlaxity of the joints and skin | |||||||||

| Epileptic seizure | No clinically observed seizures | NM | + | – | NM | + intractable | atonic or absence seizures | NM | ||||

| MRI abnormalities | enlarged bilateral lateral ventricles at 5 months old | NM | NM | NM |

a prominence of subarachnoid space, predominantly frontal, ventriculomegaly and mega cisterna magna |

mild dilatation of the lateral ventricles, a segmental thinning of the posterior part of the body of the corpus callosum |

NM | Normal at 3 y 5 m | ||||

| EEG abnormalities | spike and slow wave colligation and multi-spike and slow waves in bilateral occipital and posterior temporal region, as well as rapid rhythm distribution in the occipital area | NM | NM | NM | Normal | NM | NM | frequent epileptiform discharges during sleep in the left parietotemporal region and in the right centrotemporal region in absence of continuous spikes and waves during slow-wave sleep | ||||

| Literature | [12] | [11] | Proportion (for the 18 patients who phenotypes are reported) | |||||||||

| P14 | P20 | P21 | P22 | P23 | P28 | P32 | P33 | P35 | ||||

| Mutations | c.6485C > T (Thr2162Met) | c.2597C > T (Pro866Leu) | c.6488C > T (Ser2163Leu) | c.2930C > T (Ala977Val) | c.6488C > T (Ser2163Leu) | c.2605C > T (Pro869Ser) | c.6530C > A (Ser2177Tyr) | c.6005C > T (Ser2002Leu) | c.2605C > T (Pro869Ser) | c.3392G > A (Cys1131Tyr) | ||

| Inheritance | De novo | De novo | NM | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | ||

| Exon | 30 | 15 | 30 | 16 | 30 | 15 | 31 | 27 | 15 | 17 | ||

| Domain | C-terminal domain | C-terminal domain | C-terminal domain | C-terminal domain | C-terminal domain | |||||||

| SIFT | damaging | damaging | damaging | tolerated | damaging | damaging | damaging | damaging | ||||

| Polyphen2 | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | probably damaging | ||

| Mutation taster | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | disease causing | ||

| ID | + | +(severe) | + (severe) | + | + (severe) | + | + | + | + | + | 18/18 (100%) | |

| Speech impairment | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 16/18 (88.9%) | |

| Delayed milestones | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 15/18 (83.3%) | |

| Growth parameter | weight | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | low | 3/18 (16.7%) |

| height | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | short | 2/18 (11.1%) | |

| Head deformities | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | 1/18 (5.6%) | |

| Behavioral difficulty/autism | – | Autistic features | Autistic features |

Autistic features and behavioral troubles |

– | NM |

Autistic features and behavioral troubles |

– | – | – | 10/18 (55.6%) | |

| Hypo- or hyper-tonia | – | Hypotonia | Hypotonia | – | Hypotonia | – | Hypotonia | Hypotonia | Hypotonia /Feeding difficulties |

Severe Hypotonia/Feeding difficulties |

12/18 (66.7%) | |

| Craniofacial deformity and other dysmorphic features |

hypotonic open-mouth, Thin vermillon border |

Hypotonic open-mouth, Bulbous nasal tip |

Hypotonic open-mouth, Bulbous nasal tip |

– |

Up-slanting palpebral fissures, Bulbous nasal tip, Cupid-bow upper lip, Hypotonic open-mouth, Thin vermillon border, Deep philtrum |

Up-slanting palpebral fissures, Bulbous nasal tip, Cupid-bow upper lip, Hypotonic open-mouth, Thin vermillon border, Deep philtrum, clinodactyly |

Bilateral club foot |

Up-slanting palpebral fissures, Bulbous nasal tip, Thin vermillon border, ectopic anus, bilateral talipes, colo-bomatous micro-phtalmia |

Up-slanting palpebral fissures, Bulbous nasal tip, Cupid-bow upper lip, Hypotonic open-mouth, Thin vermillon border, Deep philtrum |

Displaced right pupil, bilateral microphthalmia, irido-corneal synechiae on the left, frontal bossing, short palpebral fissures, long eye lashes, broad straight eyebrows, depressed nasal bridge, Open mouth appearance, protrusion of the tongue |

15/18 (83.3%) | |

| Cardiac anomalies | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | coarctation of the aorta | NI | patent foramen ovale | NI | NI | 5/18 (27.8%) | |

| Urinary system | Kidney cysts | NM | NM | NM | NM | double ureter | NM | NM | NM | NM | 3/18 (16.7%) | |

| Miscellaneous | Nystagmus, craniosynostosis, ataxia | Vertebral artery occlusion, ataxia | Intrauterine growth retardation | Ataxia | Intrauterine growth retardation |

Hearing Impairment, myopia |

Inguinal hernia in neonatal period, spastic paraparesis, dystonic movements of the extremities and the tongue, | |||||

| Epileptic seizure | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | 8/18 (44.4%) | |

| MRI abnormalities | Normal | Normal | Normal | Focal cortical dysplasia | NM | Hypomyelination | NM | Ventriculo-Megaly | Diffuse cortical atrophy | a slightly enlarged ventricular system, partial agenesis of the corpus callosum, and a Dandy-Walker variant | 8/12 (66.7%) | |

| EEG abnormalities | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | 2/18 (11.1%) | |

NM Not mentioned, NI Not involved, dTGA dextro-looped transposition of the great arteries

Methods

Target capture and sequencing

After obtaining informed consent from her parents, peripheral blood of the proband and her parents was sent to Guangzhou Jiajian Medical Testing Co., Ltd. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the Solpure Blood DNA Kit (Magen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The genomic DNA of the proband and her parents was then fragmented by the Q800R Sonicator (Qsonica) to generate 300–500 bp insert fragments. The paired-end libraries were prepared following the Illumina library preparation protocol. Custom-designed NimbleGen SeqCap probes (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, Wis) were used for in-solution hybridization to enrich target sequences. Enriched DNA samples were indexed and sequenced on a NextSeq500 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, Calif) with 100,150 cycles of single end reads, according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Variant annotation and interpretation

Primary data came in fastq form after image analysis, and base calling was conducted using the Illumina Pipeline. The data were filtered to generate ‘clean reads’ by removing adaptors and low-quality reads (Q20). Sequencing reads were mapped to the reference human genome version hg19 (2009–02 release, http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Nucleotide changes observed in aligned reads were called and reviewed by using NextGENe software (SoftGenetics, State College, Pa). In addition to the detection of deleterious mutations and novel single nucleotide variants, a coverage-based algorithm developed in-house, eCNVscan, was used to detect large exonic deletions and duplications. The normalized coverage depth of each exon of a test sample was compared with the mean coverage of the same exon in the reference file to detect copy number variants (CNVs). Sequence variants were annotated using population and literature databases including 1000 Genomes, dbSNP, GnomAD, Clinvar, HGMD and OMIM. Some online software programs were used to analyze the structure of the protein, predict the conservation domain and function domain and perform the multiple sequence alignment. Variant interpretation was performed according to the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines [20]. GnomAD, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/; Clinvar, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) http://omim.org/; 1000 Genomes, http://www.1000genomes.org/.

Review of the literature

We searched PubMed and identified 10 papers describing individuals with MED13L missense mutations. Seventeen missense mutations have been reported to date.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we report a new patient with a previously reported missense mutation but with some new clinical manifestations. In addition to ID, speech impairment, motor developmental delay and hypotonia, she also exhibits congenital UPJO combined with high ureter attachment on the right, odontoprisis, appendicular muscular atrophy, scoliosis, and spontaneous facture of femur. Until 4 y 5 m, she had no clinically observed seizures, but EEG revealed spike and slow wave colligation and multi-spike and slow waves in the bilateral occipital and posterior temporal regions, as well as rapid rhythm distribution in the occipital area. However, it is not known whether epilepsy will occur in the future. The two patients P28 and P35 reported by Smol et al. with the same mutation as our case both had seizures, but the ages at first examination were 12 y and 24 y, respectively. Therefore, seizures were not observed, which may be due to the limited follow-up time. P28 did not exhibit hypotonia, but P35 and our patient have severe hypotonia. Whereas our patient exhibits autistic features, both P28 and P35 have no autism or behavioral difficulty [12]. Three patients with the same mutation did not have exactly the same clinical manifestations, demonstrating the clinical heterogeneity of patients with MED13L missense mutations. Additionally, urinary system abnormality was not a common manifestation in patients with MED13L missense mutations. However, our case had congenital UPJO, P28 with the same mutation as our case reported by Smol et al. had a double ureter, and another patient with the Thr2162Met mutation by Smol et al. had kidney cysts. Whether urinary system abnormalities are included in the clinical spectrum and how MED13L works in the process of urinary system development require further study. Other infrequent manifestations in our patient, such as odontoprisis, muscular atrophy, spontaneous fracture and scoliosis, also need more case analysis to define whether they are solely caused by MED13L mutations.

By reviewing the literature, we found 17 missense mutations in 20 patients [2, 11–19]. Compared with the overall incidence in all MED13L-related patients summarized by Torring et al. and Smol et al., patients with missense mutations have a higher incidence of seizures (44.4% vs 16%), MRI abnormalities (66.7% vs 45%) and autistic features (55.6% vs 23%) [11, 12]. The incidence of ID and hypotonia was similar to the overall incidence, but the phenotypes were much more serious. The incidence of cardiac anomalies was slightly higher than the overall incidence (27.8% vs 19%) [11].

Of the 17 mutations, 2 (11.8%) were located in the N-terminal domain, 8 (47%) were located in the highly conserved C-terminal domain, 1 of them (Asp860Gly) was located in an α-helical sequence stretch spanning residues Val858-Met864, and replacement of Asp860 by a flexible glycine decreased the helix stability, thereby affecting the secondary structure of MED13L [14]. Another mutation, Arg1416His, was located in the MID domain of the MedPIWI module. MedPIWI is the core globular domain of the Med13 protein. Med13 is a member of the CDK8 subcomplex of the Mediator transcriptional coactivator complex. The MedPIWI module in Med13 is predicted to bind double-stranded nucleic acids, triggering the experimentally observed conformational switch in the CDK8 subcomplex, which regulates the Mediator complex (Fig. 3). By analysis with SIFT, Polyphen2 and Mutation Taster, all the mutations except Prol1761Leu were predicted to be pathogenic by at least two of the prediction software programs. The mutation Prol1761Leu was predicted to be tolerated, benign, and polymorphic by SIFT, Polyphen2 and Mutation Taster, respectively. However, the mRNA expression levels of MED13L are significantly decreased, as revealed by quantitative RT-PCR, and are supposed to be pathogenic [19]. Therefore, in regard to a missense mutation that was predicted to be benign by software, while the clinical manifestations are highly coincident with MED13L-related disorder, researchers or clinicians should carry out further functional experiments to define the pathogenicity of the mutation.

Fig. 3.

The locations of the reported 17 missense mutations. Most of them located in exon 15–31. 2 (11.8%) were located in the N-terminal domain, 8 (47%) were located in the highly conserved C-terminal domain, 1 of them (Asp860Gly) was located in an α-helical sequence stretch spanning residues Val858-Met864, Another mutation, Arg1416His, was located in the MID domain of the MedPIWI module. MedPIWI is the core globular domain of the Med13 protein

In this paper, we describe a new patient with MED13L missense mutation who exhibited some infrequent manifestations except common phenotypes, which may broaden the known clinical spectrum. Additionally, we review the literature to summarize patients’ phenotypes and features of all reported missense mutations. We also found that patients with missense mutations have a higher incidence of seizures, MRI abnormalities, autistic features and cardiac anomalies. They also have more severe ID and hypotonia, which is consistent with the literature [12]. We need more functional experiments to demonstrate why patients carrying missense mutations have more severe phenotypes. Our case further demonstrates that Pro869Ser is a hotspot mutation of the MED13L gene.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient and her parents for kind cooperation.

Abbreviations

- ID

Intellectual disability

- DD

Developmental delay

- CHD

Congenital heart disease

- WES

Whole-exome sequencing

- CNV

Copy number variants

- UPJO

Ureteropelvic junction obstruction

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ACMG

American College of Medical Genetics

Authors’ contributions

Zhi Yi: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing-Original Draft; Ying Zhang: Conceptualization, Data Curation; Zhenfeng Song: Formal analysis; Hong Pan: Writing-Review & Editing; Chengqing Yang: Validation; Fei Li: Investigation; Jiao Xue: Visualization; Zhenghai Qu: Supervision, Resources, Project administration. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript, participated in its revision and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding has been received from any person or organization for any purpose of this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are all shown in the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study approval and ethical clearance was obtained from the affiliated hospital of Qingdao university. Written consent was obtained from the guardian of the child prior to data collection.

Consent for publication

We obtained the written consent for publication from the guardian of the patient.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sato S, Tomomori-Sato C, Parmely TJ, Florens L, Zybailov B, Swanson SK, et al. A set of consensus mammalian mediator subunits identified by multidimensional protein identification technology. Mol Cell. 2004;14:685–691. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muncke N, Jung C, Rudiger H, Ulmer H, Roeth R, Hubert A, et al. Missense mutations and gene interruption in PROSIT240, a novel TRAP240-like gene, in patients with congenital heart defect (transposition of the great arteries) Circulation. 2003;108:2843–2850. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000103684.77636.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musante L, Bartsch O, Ropers HH, Kalscheuer VM. cDNA cloning and characterization of the human THRAP2 gene which maps to chromosome 12q24, and its mouse ortholog Thrap2. Gene. 2004;332:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asadollahi R, Oneda B, Sheth F, Azzarello-Burri S, Baldinger R, Joset P, et al. Dosage changes of MED13L further delineate its role in congenital heart defects and intellectual disability. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doco-Fenzy M, Genevieve D, Sarda P, Edery P, Isidor B, Jost B, et al. Impaired development of neural-crest cell-derived organs and intellectual disability caused by MED13L haploinsufficiency. J Med Genet. 2014;35:1311–1320. doi: 10.1002/humu.22636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adegbola A, Musante L, Callewaert B, Maciel P, Hu H, Isidor B, et al. Redefining the MED13L syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:1308–1317. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cafiero C, Marangi G, Orteschi D, Ali M, Asaro A, Ponzi E, et al. Novel de novo heterozygous loss-of-function variants in MED13L and further delineation of the MED13L haploinsufficiency syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:1499–1504. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Haelst MM, Monroe GR, Duran K, van Binsbergen E, Breur JM, Giltay JC, et al. Further confirmation of the MED13L haploinsufficiency syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:135–138. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto T. MED13L haploinsufficiency syndrome: a de novo frameshift and recurrent intragenic deletions due to parental mosaicism. Clin Case Rep. 2017;173:1264–1269. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon CT, Chopra M. MED13L loss-of-function variants in two patients with syndromic Pierre Robin sequence. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176:181–186. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torring PM, Larsen MJ, Brasch-Andersen C, Krogh LN, Kibaek M, Laulund L, et al. Is MED13L-related intellectual disability a recognizable syndrome? Eur J Med Genet. 2019;62:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smol T, Petit F, Piton A, Keren B, Sanlaville D, Afenjar A, et al. MED13L-related intellectual disability: involvement of missense variants and delineation of the phenotype. Neurogenetics. 2018;19:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s10048-018-0541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiatt SM, Bowling KM, Prokop JW, Engel KL, Cochran JN, Bebin EM, et al. Language and cognitive impairment associated with a novel p.Cys63Arg change in the MED13L transcriptional regulator. Hum Genet. 2018;9:83–91. doi: 10.1159/000485638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asadollahi R, Zweier M, Gogoll L, Schiffmann R, Sticht H, Steindl K, et al. Genotype-phenotype evaluation of MED13L defects in the light of a novel truncating and a recurrent missense mutation. Eur J Med Genet. 2017;60:451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Najmabadi H, Hu H, Garshasbi M, Zemojtel T, Abedini SS, Chen W, et al. Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature. 2011;478:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilissen C, Hehir-Kwa JY, Thung DT, van de Vorst M, van Bon BW, Willemsen MH, et al. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature. 2014;511:344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Codina-Sola M, Rodriguez-Santiago B, Homs A, Santoyo J, Rigau M, Aznar-Lain G, et al. Integrated analysis of whole-exome sequencing and transcriptome profiling in males with autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism. 2015;6:21. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0017-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caro-Llopis A, Rosello M, Orellana C, Oltra S, Monfort S, Mayo S, et al. De novo mutations in genes of mediator complex causing syndromic intellectual disability: mediatorpathy or transcriptomopathy? Pediatr Res. 2016;80:809–815. doi: 10.1038/pr.2016.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullegama SV, Jensik P, Li C, Dorrani N, Kantarci S, Blumberg B, et al. Coupling clinical exome sequencing with functional characterization studies to diagnose a patient with familial Mediterranean fever and MED13L haploinsufficiency syndromes. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5:833–840. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are all shown in the manuscript.