Abstract

With the advancements in precision medicine and health care reform, it is critical that genetic counseling practice respond to emerging evidence to maximize client benefit. The objective of this review was to synthesize evidence on outcomes from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of genetic counseling to inform clinical practice. Seven databases were searched in conducting this review. Studies were selected for inclusion if they were: (a) RCTs published from 1990 to 2015, and (b) assessed a direct outcome of genetic counseling. Extracted data included study population, aims, and outcomes. Risk of bias was evaluated using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions guidelines. A review of 1654 abstracts identified 58 publications of 54 unique RCTs that met inclusion criteria, the vast majority of which were conducted in cancer genetic counseling setting. Twenty-seven publications assessed ‘enhancements’ to genetic counseling, and 31 publications compared delivery modes. The methodological rigor varied considerably, highlighting the need for attention to quality criteria in RCT design. While most studies assessed several client outcomes hypothesized to be affected by genetic counseling (e.g., psychological wellbeing, knowledge, perceived risk, patient satisfaction), disparate validated and reliable scales and other assessments were often used to evaluate the same outcome(s). This limits opportunity to compare findings across studies. While RCTs of genetic counseling demonstrate enhanced client outcomes in a number of studies and pave the way to evidence-based practice, the heterogeneity of the research questions suggest an important need for more complementary studies with consistent outcome assessments.

Keywords: Genetic counseling, Randomized controlled trials, Patient outcomes, Evidence-based practice, Genetic counseling outcomes, Psychological wellbeing, Genetics knowledge, Risk perception, Patient satisfaction

Introduction

In the eras of precision and genomic medicine, it is critical that research on genetic counseling outcomes excels, and that client outcomes are used to inform evidence-based practice. Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) can inform design of interventions to improve clinical care. The sheer number of published RCTs is testament to advances in genetic counseling research quality. To enhance practice, recognition of existing evidence supporting effective interventions is critical, and championing consistent use of complementary research design and assessment is needed. Applying well-founded research findings to clinical practice can advance the practice of genetic counseling and inform development of advanced practice guidelines.

Randomized Controlled Trials

RCTs are designed to answer research questions that directly affect clinical practice, treatment interventions, and professional guidelines. The design randomly assigns participants to mutually exclusive groups to assess the efficacy of distinct interventions while controlling for variables across groups. This direct comparison with minimal effect of confounding variables can lead to empirically robust findings. However, not all RCTs are created equal, and methodological rigor still needs to be evaluated to interpret the strength of findings (Sibbald and Roland 1998). Ideally, these experiments should be replicated to affirm or dispute original findings and thus, more fully answer the original research question. Data from RCTs top of the hierarchy of evidence, second only to systematic literature reviews (Barton 2000). The high-quality evidence from RCTs can be used to design downstream intervention research and to inform clinical practice. Evidence-based practices are more effective, and associated with increased positive patient outcomes (Kitson et al. 1998; Youngblut and Brooten 2001).

Genetic Counseling Outcomes

Identifying clinically relevant and measurable genetic counseling client outcomes is essential to assessing the effectiveness of clinical practice (Biesecker 2001). Bernhardt et al. (2000) elicited genetic counseling goals from experienced genetic counselors and a patient sample. Counselors cited education and provision of psychosocial support as primary goals, whereas patients described attending genetic counseling with few preconceived goals: patients reported being pleasantly surprised by the counseling, and described the experience as a positive interpersonal interaction and connection (Bernhardt et al. 2000). Long-term outcomes valued by patients were anticipatory guidance about the condition in their family and improved family communication.

In an effort to develop an assessment tool, McAllister et al. (2011) queried genetics patients about their perceptions of service outcomes. Patient perceptions of benefits led to design of the Genetic Counseling Outcome Scale. While the scale is populated with items representing outcomes of medical genetics services, a number of items on this scale such as “I can make decisions about the condition that may change my child(ren)’s future / the future of any child(ren) I may have” and “I can see that good things have come from having this condition in my family” represent feasible outcomes of genetic counseling.

Recent efforts to catalogue key genetic counseling outcomes elicited from focus groups with genetic counselors reflect early evidence of the genetic counseling outcomes from the provider’s viewpoint (Redlinger-Grosse et al. 2016; Zierhut et al. 2016). Yet, these listings include both patient outcomes and professional competencies. Patient outcomes address benefits of genetic counseling: increasing understanding, enhancing coping and adaptation, facilitating informed choice, and mitigating health risks. Alongside them appear outcomes that address the expertise of genetic counselors: providing accurate information, ordering appropriate testing, interpreting risks accurately, recommending appropriate management, and reducing inappropriate use of services. Certainly, clients benefit from competent providers; however, health services outcomes are primarily used to ensure professional standards, justify services, and demonstrate cost effectiveness. Practice outcomes are of paramount importance in assessing patient benefit from genetic counseling, and RCTs offer a rigorous method to control for the effects of confounding variables on those outcomes. Our systematic literature review yields key patient outcomes for further investigation across clinical settings.

While direct queries from patients and providers are useful in generating outcomes, particularly when the outcomes differ between these groups, a more objective source of intended outcomes is evidence from experimental studies. Using well-defined and endorsed genetic counseling outcomes, studies can achieve greater consistency in measurement when assessing the effectiveness of genetic counseling. Use of standard patient outcomes further allows for cross-comparison of findings and ultimately meta-analyses. Such efforts can provide the evidence upon which practice can be improved to enhance patient-centered care. The primary objective of this systematic review is to summarize 25 years of published RCTs that highlight genetic counseling client outcomes by synthesizing a narrative of enhanced client outcomes, assessing the quality of data and relevance for clinical practice, and if feasible, conducting a meta-analysis of outcome data. Secondary goals are to promote professional consensus on desirable outcomes for genetic counseling clients (and valid, reliable methods for assessing them), and to identify key research questions to enhance client outcomes that require further study. This project represents the first major systematic review of RCTs of genetic counseling, and strives to inform clinical practice and future study design.

Methods

Search Strategy

Reports of original research studies, systematic and process reviews on outcomes of genetic counseling were reviewed. Publications in peer-reviewed journals from 1990 to 2015 were identified in a comprehensive search via PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, CRD Database and National Research Register searches. Database searches were initially conducted using the keyword combinations including ‘genetic counseling outcomes,’ ‘genetic counseling goals,’ ‘genetic counseling evidence,’ and ‘genetic testing’ with related search terms. Upon further assessment, an updated search was conducted on 01/10/16 using the original keyword combinations as well as ‘information,’ ‘education,’ and related search terms.1 For the purpose of this review, only randomized controlled trials using patient outcomes of genetic counseling were included.

Selection Criteria

After a preliminary review of RCTs assessing genetic counseling outcomes, we elected to employ broad selection criteria to maximize the literature reviewed for eligibility. Our inclusion criteria dictated English-language publications employing a randomized controlled trial with at least one primary study aim referencing an outcome of genetic counseling. Studies that were not peer-reviewed original research or were published outside of the last 25 years were excluded.

Study Selection

We reviewed and evaluated each abstract in the literature search using the selection criteria and disagreements were resolved by discussion. All authors were involved in the selection of appropriate publications. Each selected publication was then assessed for design, methodology and outcomes.

Data Extraction

Information regarding study population, aims, and outcomes were gleaned from each study. Many studies reported multiple outcomes among the following: psychological wellbeing, knowledge, perceived risk, satisfaction, decisional quality, information sharing, and informed choice. A Cochrane narrative synthesis of outcomes was conducted, where main findings were summarized.

Data Collection and Analysis

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias was assessed using the guidelines from two sets of criteria. First, methodologies were evaluated using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins and Green 2011), in which a set of quality assessment aims were designated as “low risk” if the aim was fully met, “medium risk” if the aim was partially met, or “high risk” if the aim was not met. An aim was evaluated as unclear if there was not enough information provided for assessment. A study was considered to have an overall low risk of bias if “low risk” was assigned to four out of six of the categories. Second, methodologies were evaluated using the Updated Method Guidelines for Systematic Reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group (Van Tulder et al. 2003), by which articles were considered low risk if they adequately fulfilled six out of the 11 categories represented.

Results

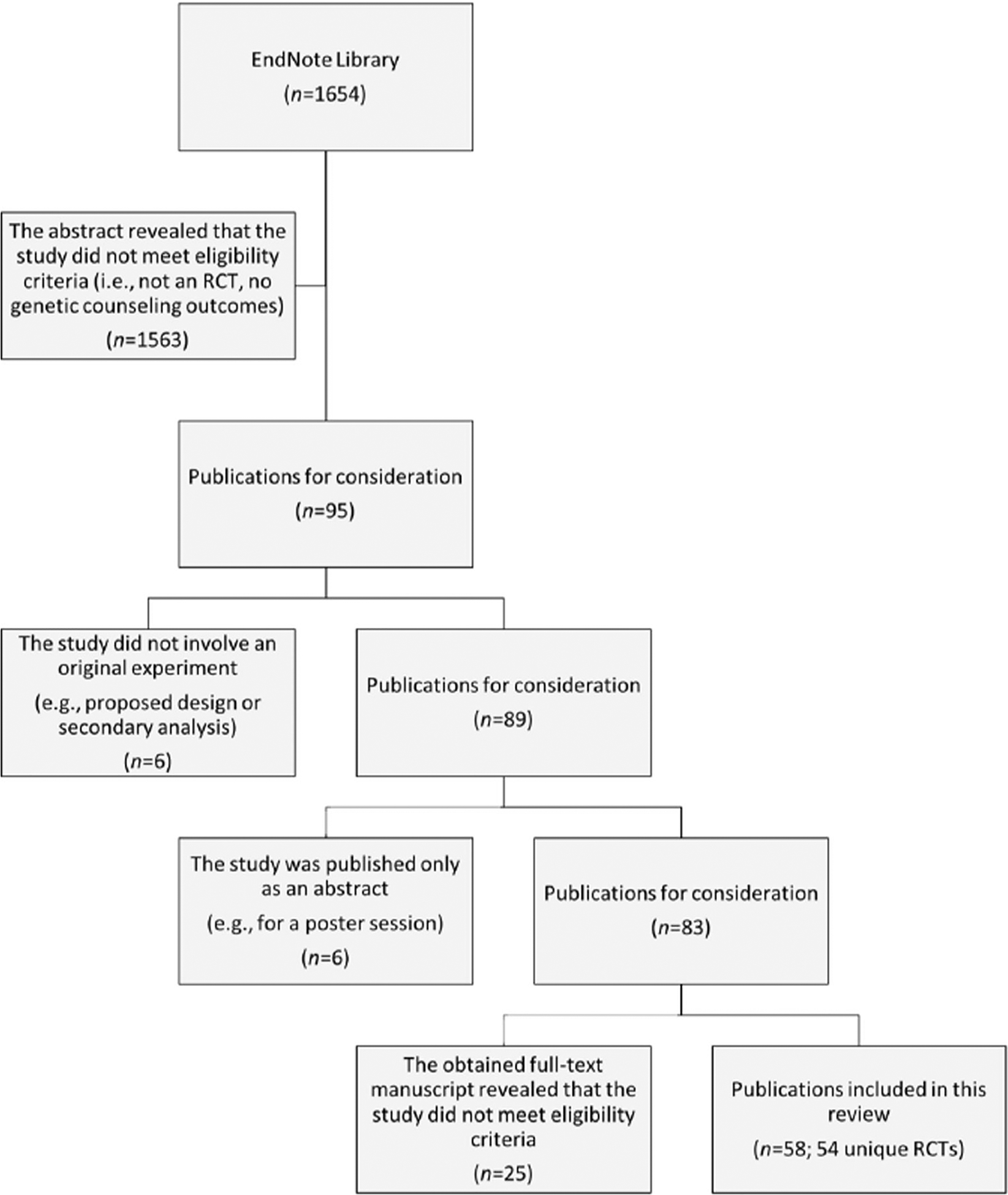

One thousand six hundred fifty-four citations were returned by our set of search queries, 1563 of which were excluded based upon the information contained in the abstract. Ultimately, 58 publications describing 54 unique RCTs met inclusion criteria; the selection process is depicted in Fig. 1. The studies included in this review vary widely, investigating a broad range of questions in genetic counseling. Due to dissimilarity in setting, inclusion criteria, and importantly, outcome characterization and assessment, a meta-analysis was not feasible. However, comparisons among similar studies provide initial evidence to guide practice, specifically those investigating delivery modes. Studies included in the review are summarized in Table 1 (RCTs comparing modes of delivery) and Table 2 (RCTs comparing counseling strategies) in terms of sample characteristics, objectives, and major findings.

Fig. 1.

A visual representation of the process of selecting the 58 publications (reporting on 54 unique RCTs) included in this review from the 1654 abstracts returned by the literature search

Table 1.

Summary of studies focused on a comparison of modes of delivery

| Title | Samplea: N, Age, Characteristics | Aim | Finding Highlights (Selected Outcomes: Psychological Wellbeing [A], Knowledge [B], Perceived Risk [C], Satisfaction [D], Genetic Testing/Screening Intentions [E] Genetic Testing Uptake [F], Decision Quality [G], Medical Management / Health Behavior [H], Sharing of Information [I], & Informed Choice [J] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temme et at (2015) | 1. Assessment of parental understanding of positive newborn screening results and carrier sta tus for Cystic Fibrosis with the use of a short educational video | 96 participants (mean 29.4y) who have a child with a positive newborn screening for Cystic Fibrosis (CF) and one identified CFTR mutation, but have no other children with CF | Evaluate the impact of augmenting genetic counseling with a short educational video in terms of parents’ knowledge about the genetics of CF and their child’s carrier status. |

|

| Butrick et at (2015) | 2. Disparities in uptake of BRCA1/2 genetic testing in a randomized trial of telephone counseling | 669 self-referred or physician-referred women (mean 48y) seeking BRCA1/2 genetic counseling | Compare in-person to telephone-based counseling by a genetic counselor in terms of genetic testing uptake among women at high risk for hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. |

|

| Buchanan et at (2015) | 3. Randomized trial of telegenetics vs. in-person cancer genetic counseling: Cost, patient satisfaction and attendance | 162 participants (mean 51.3y) referred to cancer genetic counseling in four rural oncology clinics | Compare telegenetics to in-person genetic counseling in terms of cost, satisfaction, and attendance. |

|

| Yee et al. (2014) | 4. A randomized trial of a prenatal genetic testing interactive computerized information aid | 150 women (mean 26.6y) with a gestational age 6–26wk who had not yet received any prenatal testing | Evaluate the impact of augmenting provider-based counseling with an interactive computer program on patients’ knowledge about genetic screening and diagnostic concepts. |

|

| Wevers et at (2014) | 5. Impact of rapid genetic counselling and testing on the decision to undergo immediate or delayed prophylactic mastectomy in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients: Findings from a randomised controlled trial | 265 women newly diagnosed with breast cancer (mean age at diagnosis 44.9y) and ≥10% BRCA1/2 mutation risk in the Netherlands | Compare rapid genetic counselling and testing (RGCT; result disclosure within 4 weeks) to routine testing (result disclosure after 4 months or more) provided by a clinical geneticist in terms of choice of surgery. |

|

| Schwartz et al (2014) | 6. Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditaiy breast and ovarian cancer | 669 women (mean 48y) with a minimum 10% risk for BRCA1/2 mutation and without a newly diagnosed or metastatic cancer | Compare telephone delivery to in-person delivery of BRCA1/2 counseling by a genetic counselor. |

|

| Lowery et al. (2014) | 7. A randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in members of high-risk families in the colorectal cancer family registry and cancer genetics network | 632 men and women (≥2 ly) unaffected but at high risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) due to family history | Compare a tailored telephone-based counseling intervention delivered by trained interviewers to a mailed packet in terms of adherence to colonoscopy screening. |

|

| Kinney et al. (2014) | 8. Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: A cluster randomized trial | 901 women (mean 56. ly) who were breast or ovarian cancer patients and at-risk females of relatives positive for BRCA1/2 mutations | Compare telephone to in-person counseling by a genetic counselor in terms of testing uptake and changes in psychosocial measures. |

|

| Hag a et al (2014) | 9. Impact of delivery models on understanding genomic risk for type 2 diabetes | 300 non-diabetic participants (44% aged 18–29y) recruited from Durham, NC | Compare an online delivery model to in-person counseling by a genetic counselor in terms of understanding genomic risk and adopting healthy behaviors. |

|

| Green et al (2014) | 10. A randomized noninferiority trial of condensed protocols for genetic risk disclosure of Alzheimer’s disease | 343 asymptomatic adults (mean 58.3y) with a first-degree relative affected by Alzheimer’s disease and unaffected by severe anxiety or depression | Compare standard protocols (SP-GC) with condensed protocols delivered by genetic counselors (CP-GC) and physicians (CP-MD) for disclosing APOE genotype and concordant risk of Alzheimer’s disease. |

|

| Hanprasertpong et al (2013) | 11. Compa rison of the effectiveness of different counseling methods before second trimester genetic amniocentesis in Thailand | 321 pregnant women (mean 37.7y) scheduled for their second trimester genetic amniocentesis because of maternal age > 35y in Thailand | Compare computer-assisted instruction (CAI) to leaflet self-reading (LSR) before individual counseling with a senior midwife in a developing country. |

|

| Platten et al (2012) | 12. The use of telephone in genetic counseling versus in-person counseling: A randomized study on counselees’ outcome | 215 patients (mean 45y) seeking oncogenetic counseling in Stockholm County, Sweden | Compare oncogenetic nurse counseling conducted via telephone to traditional in-person counseling. |

|

| Hooker et al (2011) | 13. Longitudinal changes in patient distress following interactive decision aid use among BRCA1/2 earners: A randomized trial | 214 women (25–75y) with a positive BRCA1/2 mutation test but no metastatic breast or ovarian cancer | Evaluate the impact of augmenting breast cancer risk management counseling by a genetic counselor with subsequent provision of a computer-based, interactive decision aid. |

|

| Castellani et al (2011) | 14. An interactive computer program can effectively educate potential users of cystic fibrosis carrier tests | 44 participants (mean 37.9y) from infertile couples having CTFR mutation analysis as part of an assisted reproduction protocol in Italy | Compare a computer-based, educational tool with traditional counseling sessions by a trained geneticist for CF carrier testing in terms of knowledge and understanding. |

|

| Hwa et al (2010) | 15. Informed consent for antenatal serum screening for Down syndrome | 193 women (mean 31y) at 15–2 lwk gestation in Taiwan | Evaluate the impact of providing a trained research counselor with results from a questionnaire assessing patients’ understanding of Down syndrome. |

|

| Bowen and Powers (2010) | 16. Effects of a mail and telephone intervention on breast health behaviors | 1510 women (18–74y) not previously diagnosed with cancer | Evaluate the impact of a mail and telephone intervention to improve breast health behavior while maintaining quality of life for women with a family history (delivered by a genetic counselor) and without (delivered by a health counselor). |

|

| Schwartz et al (2009) | 17. Randomized trial of a decision aid for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: Impact on measures of decision making and satisfaction | 214 women (mean 44y) with a positive BRCA1/2 mutation test result | Evaluate the impact of augmenting standard genetic counseling with a computer-based interactive decision aid in helping women with a BRCA1/2 mutation consider their options for risk management and maximize satisfaction. |

|

| Jenkins et al (2007) | 18. Randomized comparison of phone versus in-person BRCA1/2 predisposition genetic test result disclosure counseling | 111 men and women (median 45y) with BRCA1/2 mutation or a breast/ovarian cancer diagnosis | Compare phone to in-person disclosure of results by advance-practice nurses for BRCA1/2 predisposition genetic testing. |

|

| Helmes et al (2006) | 19. Results of a randomized study of telephone versus in-person breast cancer risk counseling | 340 women (mean 41y) with no personal history of breast/ovarian cancer | Compare in-person counseling and telephone counseling by a genetic counselor to control (no counseling). |

|

| Bowen et al (2006) | 20. Effects of counseling Ashkenazi Jewish women about breast cancer risk | 221 Ashkenazi Jewish women (mean 47y) with no personal history of breast cancer | Compare individual genetic counseling and psychosocial group counseling to control in terms of breast cancer worry, risk perception, and interest in genetic testing. |

|

| Wang et al (2005) | 21. Genetic counseling for BRCA1/2: A randomized controlled trial of two strategies to facilitate the education and counseling process | 197 women (mean 44.5y) from the Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk Evaluation Program (BOCREP) | Evaluate the impact of augmenting standard genetic counseling with two strategies: a CD-ROM computer program for patients and a feedback checklist for the genetic counselor. |

|

| Hunter et al. (2005) | 22. A randomized trial comparing alternative approaches to prenatal diagnosis counseling in advanced maternal age patients | 352 women (mean 36.8y) of advanced maternal age with no family history of genetic disorders in Canada | Compare individual genetic counseling, group genetic counseling, and a decision aid (explained by a genetic counselor) regarding prenatal diagnosis for women of advanced maternal age. |

|

| Green et al (2005) | 23. Use of an educational computer program before genetic counseling for breast cancer susceptibility: Effects on duration and content of counseling sessions | 211 women (mean 44y) referred to a genetic counselor for evaluation of breast cancer risk | Evaluate the impact of augmenting standard genetic counseling with a computer-based decision aid for educating women about BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing. |

|

| Calzone et al (2005) | 24. Randomized comparison of group versus individual genetic education and counseling for familial breast and/or ovarian cancer | 142 men and women (25–68y) with a known BRCA1/2 mutation or a breast/ovarian cancer diagnosis | Compare pretest education and counseling for breast cancer by advanced-practice nurses in a group setting to that provided on an individual basis by the same nurses. |

|

| Green et al (2004) | 25. Effect of a computer-based decision aid on knowledge, perceptions, and intentions about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility | 211 women (mean 44y) referred for genetic counseling due to personal or family history of breast cancer | Evaluate the impact of augmenting standard genetic counseling with a computer-based decision aid for educating women about BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing. |

|

| Bowen et al (2004) | 26. Breast cancer risk counseling improves women’s functioning | 354 women (mean 42y) with a family history of breast cancer | Compare individual genetic counseling (a 2-h session) and psychosocial group counseling (4 2-h sessions with 4–6 others) to control. |

|

| Bowen et al (2002) | 27. Effects of risk counseling on interest in breast cancer genetic testing for lower risk women | 317 women (mean 42.4y) with some familial history of breast cancer but no indications of autosomal dominant genetic mutation | Compare individual genetic counseling and psychosocial group counseling to a control condition in terms of interest in genetic testing. |

|

| Schwartz et al (2001) | 28. Impact of educational print materials on knowledge, attitudes, and interest in BRCA1/BRCA2 testing among Ashkenazi Jewish women | 391 Ashkenazi Jewish women (18–83y) without a family history suggestive of hereditary breast- ovarian carcinoma | Compare a brief educational booklet on BRCA1/BRCA2 testing to one on signs and symptoms of breast carcinoma in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and interest in testing. |

|

| Green et al (2001a) | 29. Education about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: Patient preferences for a computer program or genetic counselor | 72 women (mean 40y) with a first-degree relative diagnosed with breast cancer | Compare face-to-face education and counseling by a genetic counselor to education by an interactive computer program. |

|

| Green et al (2001b) | 30. An interactive computer program can effectively educate patients about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility | 72 women (mean 44y) with a first-degree relative diagnosed with breast cancer | Compare face-to-face education and counseling by a genetic counselor with education by an interactive computer program. |

|

| Miedzybrodzka et al (1995) | 31. Antenatal screening for carriers of cystic fibrosis: Randomized trial of stepwise v couple screening | 2002 women (mean 27.7y) with no family history of cystic fibrosis recruited from an antenatal clinic in Scotland | Compare stepwise to couple approaches in antenatal carrier screening for cystic fibrosis (CF) by a clinical geneticist. |

|

Unless otherwise noted in this Sample column, the study was conducted in the United States of America

Table 2.

Summary of studies focused on a comparison of counseling strategies

| Title | Samplea: N, Age, Characteristics | Aim | Finding Highlights (Selected Outcomes: Psychological Wellbeing [A], Knowledge [B], Perceived Risk [C], Satisfaction [D], Genetic Testing/Screening Intentions [E] Genetic Testing Uptake [F], Decision Quality [G], Medical Management / Health Behavior [H], Sharing of Information [I], & Informed Choice [J] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hodgson et al (2015) | 32. Outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of a complex genetic counselling intervention to improve family communication | 95 probands or parents of probands (mean 47.6y) recruited from genetics clinics in six public hospitals in Victoria, Australia | Evaluate the impact of augmenting standard care with three phone calls from a genetic counselor in terms of family communication about a new genetic diagnosis. | 25.6% of intervention group relatives compared with 20.9% of control group relatives made contact with genetic services. [E]

|

| Eijzenga et al (2015) | 33. Routine assessment of psychosocial problems after cancer genetic counseling: Results from a randomized controlled trial | 118 individuals (mean 49.5y) who underwent diagnostic or pre-symptomatic DNA testing and had their final counseling session prior to 12/15/12 in the Netherlands | Evaluate the impact of augmenting genetic counseling with provision of information about the counselees’ psychosocial problems to genetic counselors as part of a telephone session held 1 month after cancer genetic counseling and testing (CGCT) procedure. |

|

| Albada et al (2015) | 34. Follow-up effects of a tailored pre-counseling website with question prompt in breast cancer genetic counseling | 197 women (mean 41.35y) who were the first in their families to seek breast cancer genetic counseling in the Netherlands | Evaluate the immediate and long-term effects of a pre-counseling website with question prompts on patients receiving cancer genetic counseling. |

|

| Nishigaki et al (2014) | 35. The effect of genetic counseling for adult offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes on attitudes toward diabetes and its heredity: A randomized controlled trial | 216 individuals (mean 45.9y) with a first-degree relative with type 2 diabetes but no personal diagnosis in Tokyo, Japan | Compare a lifestyle intervention with counseling by a genetic counselor (GC + LI) and without (LI) to control (no intervention) in terms of attitudes toward diabetes and its prevention. |

|

| Kuppermann et al (2014) | 36. Effect of enhanced information, values clarification, and removal of financial barriers on use of prenatal genetic testing: A randomized clinical trial | 710 women (mean 29.25y) who were ≤20wk gestation and had not undergone any prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy | Evaluate the impact of a decision- support guide and elimination of financial barriers to testing on decision making and prenatal genetic testing uptake. |

|

| Eijzenga et al (2014) | 37. Effect of routine assessment on specific psychosocial problems on personalized communication, counselors’ awareness, and distress levels in cancer genetic counseling practice: A randomized controlled trial | 246 participants (mean 48y) referred to genetic counseling at two family cancer clinics in the Netherlands | Evaluate the impact of augmenting genetic counseling with provision of results from the Psychosocial Aspects of Hereditary Cancer (PAHC) as part of a telephone session held 1 month after cancer genetic counseling and testing procedure. |

|

| Montgomery et al (2013) | 38. Preparing individuals to communicate genetic test results to their relatives: Report of a randomized control trial | 249 women (mean 48.5y) who had BRCA1/2 testing with at least one first-degree relative with whom to share results | Compare the efficacy of a communication skills-building intervention to wellness education in preparing individuals to communicate results to family members. |

|

| Henneman et al (2013) | 39. The effectiveness of a graphical presentation in addition to a frequency format in the context of familial breast cancer risk communication: A multicenter controlled trial | 410 unaffected women (mean 41y) with breast cancer family history attending the cancer clinic for the first time in the Netherlands | Evaluate the impact of augmenting the standard frequency format of lifetime breast cancer risk with a graphical presentation (10 × 10 human icons). |

|

| Voonvinden et al (2012) | 40. The introduction of a choice to learn pre-symptomatic DNA test results for BRCA or Lynch syndrome either face-to-face or by letter | 198 asymptomatic counselees (mean 44.6y) from families in the Netherlands with a known BRCA1/2 or Lynch syndrome mutation in the Netherlands | Compare traditional test result disclosure to a procedure in which counselees are offered a choice regarding how they receive their results. |

|

| Roberts et al (2012) | 41. Effectiveness of a condensed protocol for disclosing APOE genotype and providing risk education for Alzheimer disease | 264 participants (mean 58.ly) with only one first-degree relative affected with Alzheimer’s disease (onset ≥60y) | Compare a brief educational model to the standard extended protocol for describing Alzheimer’s disease risk related to APOE allele status. |

|

| Roussi et al (2010) | 42. Enhanced counseling for women undergoing BRCA1/2 testing: Impact on knowledge and psychological distress - Results from a randomized clinical trial | 134 women (≥21y) with a family history suggestive of a hereditary pattern of breast and/or ovarian cancer | Evaluate the impact of augmenting standard genetic counseling with a 45-min, enhanced counseling intervention in role-play format from a health educator. |

|

| Halbert et al (2010) | 43. Effect of genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in African American women: A randomized trial | 139 African American and/or black women (59% ≤50y) with ≥5% risk of BRCA1/2 mutation | Compare culturally tailored counseling to standard counseling (both provided by a genetic counselor) across a cohort of randomized and non-randomized women. |

|

| Graves et al (2010) | 44. Randomized controlled trial of a psychosocial telephone counseling intervention in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers | 128 women (≥18y) who were BRCA1/2 mutation carriers without metastatic disease or recurrent ovarian cancer in Canada and the USA | Evaluate the impact of augmenting standard genetic counseling with a psychosocial counseling intervention by master’s-level mental health counselors consisting of 5 weekly telephone sessions and a mailed booklet. |

|

| Roshanai et al (2009) | 45. Does enhanced information at cancer genetic counseling improve counselees’ knowledge, risk perception, satisfaction and negotiation of information to at-risk relatives? - A randomized study | 147 men and women (median 56y) who did not suffer from any mental illnesses and read, wrote, and spoke Swedish | Evaluate the impact of augmenting genetic counseling with a subsequent session in which a specialist nurse offered extended cancer genetic information, help identifying important relatives, and an videotape from the counseling session. |

|

| Wakefield et al (2008) | 46. A randomized trial of a breast/ovarian cancer genetic testing decision aid used as a communication aid during genetic counseling | 148 women (mean 49y) who approached a familial cancer clinic within a two-year period in Australia | Evaluate the impact of a decision aid given during genetic counseling for women considering genetic testing for breast/ovarian cancer risk. |

|

| Glanz et al (2007) | 47. Effects of colon cancer risk counseling for first-degree relatives | 176 siblings and children (mean 54.4y) of colorectal cancer patients living in Hawaii | Compare culturally sensitive Colon Cancer Risk Counseling (CCRC) to General Health Counseling (GHC) by trained health or nurse educators for relatives of colorectal cancer patients. |

|

| Bennett et al (2007) | 48. A randomized controlled trial of a brief self-help coping intervention designed to reduce distress when awaiting genetic risk information | 162 women (most >40y) referred to a specific breast and ovarian cancer service in Wales | Evaluate the impact of a distraction-based coping leaflet in women undergoing genetic risk assessment for breast/ovarian cancer. |

|

| Matloff et al (2006) | 49. Healthy women with a family history of breast cancer: Impact of a tailored genetic counseling intervention on risk perception, knowledge, and menopausal therapy decision making | 64 women (mean 49y) with at least one first-degree relative with breast cancer | Evaluate the impact of a personalized risk assessment and intervention by a genetic counselor in a cohort of low- and moderate-risk women. |

|

| Charles et al (2006) | 50. Satisfaction with genetic counseling for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among African American women | 54 African American women (mean 46y) with moderate to high risk for BRCA1/2 mutation | Compare culturally tailored genetic counseling (CTGC) to standard genetic counseling (SGC), both provided by a genetic counselor. |

|

| Miller et al. (2005) | 51. Enhanced counseling for women undergoing BRCA1/2 testing: Impact on subsequent decision making about risk reduction behaviors | 77 high-risk women (most ≤50y) undergoing BRCA1/2 testing | Evaluate the impact of an enhanced counseling intervention by a health educator designed to promote well-informed decision making for risk reduction options for ovarian cancer. |

|

| Braithwaite et al (2005) | 52. Development of a risk assessment tool for women with a family history of breast cancer | 72 women (≥18y) with a first- or second-degree relative with breast cancer in the UK | Compare the genetic risk assessment in the clinical environment (GRACE) prototype to standard risk counseling from a clinical nurse specialist. |

|

| Brain et al (2005) | 53. An exploratory comparison of genetic counselling protocols for HNPCC predictive testing | 14 women and 12 men (mean 41y) currently unaffected individuals from families with an HNPCC-related mutation in Wales | Compare an extended genetic nurse specialist counseling protocol (2 sessions of education and reflection) to shortened protocol (1 session of education). |

|

| McInerney-Leo et al (2004) | 54. BRCA1/2 testing in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families: Effectiveness of problem-solving training as a counseling intervention | 212 men and women (≥18y) with a BRCA1/2 mutation | Compare a problem-solving training intervention to a client-centered intervention, including assessment of changes at follow-up 6–9 months later. |

|

| Brain et al (2000) | 55. A randomized trial of specialist genetic assessment: Psychological impact on women at different levels of familial breast cancer risk | 740 women (mean 42.6y) referred for a family history of breast cancer in Wales | Evaluate the impact of augmenting a surgical consultation with a multidisciplinary specialist risk assessment by a clinical geneticist. |

|

| Lerman et al (1999) | 56. Racial differences in testing motivation and psychological distress following pretest education for BRCA1 gene testing | 228 Caucasian and 70 African American women (18–75y) with at least one first-degree relative affected by breast or ovarian cancer | Compare a standard education model (E) to an education plus counseling model (E + C) in terms of racial differences. |

|

| Watson et aL (1998) | 57. Family history of breast cancer: What do women understand and recall about their genetic risk? | 115 women (28–7ly) with a family history of breast cancer referred for genetic counseling in London | Evaluate the impact of augmenting standard clinical geneticist consultation with provision of an audiotape of the encounter. |

|

| Lerman et al (1997) | 58. Controlled trial of pretest education approaches to enhance informed decision-making for BRCA1 gene testing | 400 women (18–75y) with one first-degree relative affected by breast or ovarian cancer | Compare education only and education plus counseling to control (waiting list) for decision-making regarding BRCA1 testing. |

|

Unless otherwise noted in this Sample column, the study was conducted in the United States of America

Study Design and Specialty Setting

Concordant with this review’s inclusion criteria, all study designs were experimental in nature. All studies used a randomized controlled design to assess the impact of a counseling intervention or delivery mode on genetic counseling patient outcomes. The majority of publications reported on studies conducted in the cancer genetics setting (n = 45). Other genetic counseling specialties were, prenatal (n = 7), adult (n = 5), and pediatrics (n = 1). RCTs of genetic counseling in the prenatal setting focused on Down syndrome (n = 1), Cystic Fibrosis carrier testing (n = 2), and prenatal diagnostic options. Studies in the adult setting centered upon Alzheimer’s disease (n = 2) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (n = 2). Lastly, the one pediatric study focused on child carrier status for Cystic Fibrosis. Refer to Table 3 for specialty distribution.

Table 3.

Frequency of specialty settings and outcomes

| Specialty settings | n (%a) |

|---|---|

| Cancer | 45 (76) |

| Prenatal | 7 (12) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 2 (3) |

| Down syndrome | 1 (2) |

| Adult | 5 (9) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 2 (3) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 2 (3) |

| Pediatrics | 1 (2) |

| Outcomes | n (%a) |

| Psychological wellbeing [A] | 40 (69) |

| Knowledge [B] | 29 (50) |

| Perceived risk [C] | 23 (40) |

| Satisfaction [D] | 20 (35) |

| Intentions to pursue genetic testing / Screening [E] | 15 (26) |

| Genetic testing uptake [F] | 11 (19) |

| Decision quality [G] | 10 (17) |

| Medical management / Health behavior [H] | 9 (16) |

| Sharing information [I] | 5 (9) |

| Informed choice [J] | 2 (5) |

These values correspond to the percentage of publications, and thus use 58 as the denominator

Sample Characteristics

The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (n = 37), while six studies each were conducted in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. The number of participants involved in each study widely varied, ranging from 26 to 2002. On average, studies consisted of 304 participants. Collectively, 16,417 genetic counseling clients are represented by these studies. Two-thirds of studies (n = 39) enrolled only women, while no studies enrolled only men. Participant age ranged from 18 years to “greater than 50 years,” with most participants in their forties. The majority of publications (n = 45) reported on studies conducted in the cancer genetics setting where inclusion criteria varied from having a personal and/or family history of cancer to being at risk for or testing positive for a BRCA1/2 or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)-related mutation. A number of studies sampled from healthy populations, requiring an absence of a cancer diagnosis or significant cancer family history. Few studies’ inclusion criteria specified ethnicity, with the exception of three studies that recruited African American women and two that recruited Jewish women. For studies of prenatal genetic counseling, advanced maternal age, infertility, and gestational age were the inclusion criteria across studies. Adult genetic counseling studies defined their inclusion criteria by family history of Alzheimer’s disease or increased risk for type II diabetes mellitus. In a study of pediatric genetic counseling, parents were eligible to enroll after their child screened positive on newborn screening for Cystic Fibrosis and one CFTR mutation was identified.

Providers and Outcomes

Eleven studies (reported in 14 publications) specified that the provider was a “certified” genetic counselor, though most described the providers as genetic counselors. Some studies involved providers other than genetic counselors including, for example, nurse counselors (n = 9) and medical geneticists (n = 7). The background of the providers was not specified in five studies. In addition to heterogeneity in provider training and expertise, participant outcome assessment was measured using a variety of scales.

The majority of RCTs assessed multiple patient outcomes following genetic counseling. Psychological wellbeing was the most frequently assessed outcome, and was reported in 69% of publications (n = 40). Psychological wellbeing was measured as feelings of anxiety, depressive symptoms, (lack of) intrusive thoughts, worries (often cancer-specific), and quality of life. Nearly all were measured using published validated and reliable scales. Depression, for example, was measured using the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Other frequently assessed outcomes included knowledge (n = 29), perceived risk (n = 23), and satisfaction (n = 20), and intentions to pursue testing or screening (or interest in undergoing testing; n = 15). Information sharing with relatives and informed choice (having sufficient relevant knowledge and making a decision in accordance with one’s attitudes toward testing) were assessed least often (n = 5 and n = 2, respectively). Varied single-item or study-specific novel scales were often used to measure risk perception and knowledge. Table 3 lists the frequencies of the top ten genetic counseling outcomes identified by this systematic literature review.

Quality Assessment

Nine of the 58 publications were evaluated as having a low risk of bias per both sets of criteria (Albada et al. 2015; Bowen et al. 2004; Brain et al. 2005; Butrick et al. 2015; Hooker et al. 2011; Kinney et al. 2014; Kuppermann et al. 2014; Montgomery et al. 2013; Roussi et al. 2010), and accordingly considered to have a strong methodology. Notably, 24 other publications satisfied sufficient categories only in the second set of criteria (Bennett et al. 2007; Bowen et al. 2002; Calzone et al. 2005; Eijzenga et al. 2014; Eijzenga et al. 2015; R. Green et al. 2014; Halbert et al. 2010; Hanprasertpong et al. 2013; Helmes et al. 2006; Henneman et al. 2013; Hodgson et al. 2015; Hunter et al. 2005; Lowery et al. 2014; Miedzybrodzka et al. 1995; Schwartz et al. 2001; Schwartz et al. 2009; Schwartz et al. 2014; Roberts et al. 2012; Roshanai et al. 2009; Wakefield et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2005; Watson et al. 1998; Wevers et al. 2014; Yee et al. 2014), while none passed only the set of criteria from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Additional details regarding the evaluations of each of the publications are given in Online Resource 1.

Quality Criteria

All but three publications explicitly stated having obtained institutional ethics board approval to protect human subjects (Hwa et al. 2010; Roberts et al. 2012; Schwartz et al. 2001). Fifty-three publications specified that participants had given informed consent before enrolling in the studies; five did not (Bowen et al. 2002, 2004; Haga et al. 2014; McInerney-Leo et al. 2004; Platten et al. 2012).

Sensitivity Analysis

Randomization and allocation concealment were successfully implemented together in only nine publications (Albada et al. 2015; Bowen et al. 2004; Brain et al. 2005; Butrick et al. 2015; Hodgson et al. 2015; Hooker et al. 2011; Kinney et al. 2014; Kuppermann et al. 2014; Roussi et al. 2010). Sixteen publications reported randomization without proper allocation concealment (Bennett et al. 2007; Bowen et al. 2002; Bowen and Powers 2010; Brain et al. 2000; Buchanan et al. 2015; Eijzenga et al. 2014; Eijzenga et al. 2015; M. Green et al. 2004; Halbert et al. 2010; Lerman et al. 1999; Montgomery et al. 2013; Schwartz et al. 2001; Schwartz et al. 2009; Schwartz et al. 2014; Wevers et al. 2014; Yee et al. 2014), and five publications adequately concealed allocations without ensuring proper randomization (Hanprasertpong et al. 2013; Hunter et al. 2005; Miedzybrodzka et al. 1995; Wakefield et al. 2008; Watson et al. 1998).

Missing Data

Participation rates were noted, and 31% of the publications had a follow-up rate that did not exceed 80% (Bennett et al. 2007; Braithwaite et al. 2005; Eijzenga et al. 2014; Eijzenga et al. 2015; Graves et al. 2010; M. Green et al. 2004; Halbert et al. 2010; Henneman et al. 2013; Hodgson et al. 2015; Lerman et al. 1997; Lerman et al. 1999; Matloff et al. 2006; Miller et al. 2005; Montgomery et al. 2013; Nishigaki et al. 2014; Platten et al. 2012; Roussi et al. 2010; Wakefield et al. 2008). Seventeen publications analyzed the data with an intention-to-treat analysis (Butrick et al. 2015; Eijzenga et al. 2014; Eijzenga et al. 2015; Graves et al. 2010; R. Green et al. 2014; Helmes et al. 2006; Hodgson et al. 2015; Hooker et al. 2011; Kinney et al. 2014; Kuppermann et al. 2014; Lowery et al. 2014; Montgomery et al. 2013; Roberts et al. 2012; Schwartz et al. 2009; Schwartz et al. 2014; Watson et al. 1998; Wevers et al. 2014). The majority of publications reported follow-up rates that did not vary greatly between the intervention and control arms, and thus attrition was not considered a risk to analytical rigor.

Overall Synthesis of Evidence

The RCTs meeting inclusion criteria could be broadly categorized into two groups: comparisons between modes of genetic counseling service delivery (such as telephone vs. in-person counseling) and comparisons between genetic counseling strategies (such as person-centered vs. problem-based counseling). These two categories of RCT differ in purpose. Comparison between delivery modes yields data on alternative approaches to genetic counseling service provision. Comparison between strategies of counseling yields data on alternative ways to engage clients to achieve desired outcomes. We review the comparative outcomes according to these two general study aims. In both categories, genetic counseling was often provided in conjunction with the offer of genetic testing. While many of the studies were inadequately designed to determine whether differences in outcomes resulted from the counseling, the testing process and outcome, or a combination of the two, those assessing counseling interventions were largely designed to capture coutcomes separate from receipt of a test result.

Studies Comparing Service Delivery Modes

Twenty-seven studies described in thirty-one publications compared ways to deliver genetic counseling services (See Table 1: same study reported in publications 2 & 6; 23 & 25; 26 & 27; and 29 & 30). Thirteen studies compared inperson counseling to either telephone counseling or interactive online platforms. These RCTs assessed the effectiveness of alternative delivery modes that consume fewer resources than in-person genetic counseling. Outcomes were most often found to be equivalent, non-inferior, or not statistically different between delivery modes; this suggests that telephone counseling or interactive online platforms may be sufficient for teaching key information about test results, specifically cancer risk status and screening and prevention strategies. Most of these RCTs (74%) assessed psychological wellbeing to ensure that these alternative, cost-effective interventions did not lead to greater distress than in-person counseling, and found they did not (Calzone et al. 2005; Graves et al. 2010; M. Green et al. 2001a; R. Green et al. 2014; Hooker et al. 2011; Hwa et al. 2010; Kinney et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014).

Four RCTs found differences in testing uptake or intentions to undergo testing between study arms (M. Green et al. 2001b; Kinney et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2005), but their implications remain unclear. In certain contexts such a finding may indicate that one delivery mode is more successful in facilitating an informed choice about whether to undergo testing. In other contexts eligible candidates may be less likely to pursue testing after telephone counseling because it requires an office visit. Thus, differences in testing uptake or intentions may not reflect differential efficacy between the delivery modes.

Further, while the majority of studies found no differences in satisfaction, two studies reported that telephone counseling yielded higher satisfaction than in-person counseling (Buchanan et al. 2015; Jenkins et al. 2007), and one found that a computer-based interactive decision aid led to higher satisfaction than usual care (Schwartz et al. 2009). In another RCT, patients preferred in-person counseling to an interactive computer platform largely based on the opportunity to ask specific questions of the counselor (M. Green et al. 2001b).

Studies Comparing Counseling Interventions

Twenty-seven studies compared two different counseling strategies or interventions (See Table 1). Of these RCTs, 17 evaluated the impact of augmenting in-person genetic counseling (or usual care) with a variety of interventions: a decision aid (Kuppermann et al. 2014; Miller et al. 2005; Wakefield et al. 2008), personalized risk assessment (Brain et al. 2000; Braithwaite et al. 2005; Matloff et al. 2006), culturally sensitive genetic counseling (Charles et al. 2006; Glanz et al. 2007; Halbert et al. 2010), and counseling approaches described as psychological (Bowen et al. 2002) and problem solving (McInerney-Leo et al. 2004). A number of these interventions were informed by health behavior or stress and coping theory. Increases in knowledge followed “enhanced” genetic counseling (Roussi et al. 2010), a coping intervention (Bennett et al. 2007), and one decision aid (Wakefield et al. 2008). Reductions in perceived cancer risk were found following psychological counseling (Bowen et al. 2002), education without counseling (Lerman et al. 1997) and risk assessment (Brain et al. 2000). Cancer worries were reduced following a culturally sensitive intervention (Charles et al. 2006), psychological counseling (Bowen et al. 2002), and risk assessment (Brain et al. 2000). Intrusive thoughts (Bennett et al. 2007) and depressive symptoms (McInerney-Leo et al. 2004) were lower in a coping and a problem-solving intervention arm, respectively. Although these significant differences offer preliminary evidence for the efficacy of these interventions to improve patient outcomes, the lack of consistency in the intervention targets, theoretical underpinnings and the outcomes assessed preclude distillation of clear evidence on the most efficatious interventions to guide genetic counseling practice.

Discussion

This systematic literature review is the largest to date summarizing 25 years of RCTs assessing outcomes of genetic counseling. The sheer number of studies meeting eligibility criteria (N = 54) reflects significant advancement in genetic counseling research, amassing evidence for improved client outcomes grounded in rigorous comparisons of both delivery modes and counseling interventions. Notable is the prevalence of assessment of psychological wellbeing in 40 of 58 publications, reflecting some consensus that it is a sought-after goal of genetic counseling. Moreover, assessment of wellbeing was achieved using valid and reliable scales from health psychology research including a lack of anxiety or depressive symptoms, low worries, few intrusive thoughts and high quality of life.

The data assembled in this review offer initial evidence that alternative delivery modes may be as effective as in-person genetic counseling for women participants at risk for hereditary cancer, as reflected by the majority of the RCTs. While there was substantial variation in types of alternative counseling interventions, there is also preliminary evidence among these studies for the benefits of graphical representation of risk information, problem-based counseling, ‘enhanced’ counseling interventions and condensed counseling sessions. Outcomes of the intervention studies can be used to generate hypotheses for future trials among sub-specialties, though larger and more diverse populations of genetic counseling clients and patients are needed before conclusions can be drawn about their effectiveness and generalizability.

Lacking from this impressive array of studies is consistency in how outcomes (e.g., psychological wellbeing) are assessed, precluding meta-analysis. Further research exploring outcomes sought by genetic counseling clients and patients across sub-specialties is greatly needed. Although progress has been made in identifying outcomes genetic counselors seek to achieve on behalf of their clients (Redlinger-Grosse et al. 2016; Zierhut et al. 2016), insufficient evidence has been solicited from end-users (Bernhardt et al. 2000). The limited data identifying outcomes from genetic counseling valued by patients highlights a critical need for advancing evidence-based practice in the era of patient-centered care.

In addition to the need for distinction of beneficial client outcomes, there is a need to identify elements of genetic counseling that may be amenable to intervention. Counseling psychology, health behavior and health communication theories should be used to inform study design and to identify appropriate constructs likely to affect outcomes. For example, self-regulation theory may be used to frame studies of decisions about use of genomic information (Cameron et al. 2017). There are communication interventions that can be used to enhance understanding of complex genetic information, such as using simple language with low literacy words and teach back for the clients to state back to the genetic counselors what they have heard. Also, to enhance understanding of risk information, ten evidence-based interventions have been suggested by Fagerlin et al. (2011) that can be assessed in RCTs of genetic counseling. More accurate risk perception may lead to more informed decision making about genomic testing and better adherence to screening recommendations, both of which could be construed as beneficial outcomes of genetic counseling. In addition to the educational goals, there is a need for attention to the relational elements of genetic counseling. For example, to convey understanding of the client’s experiences, worries, concerns, and counseling needs, genetic counselors may use reflections such as paraphrasing and summarization, and empathic statements about the client’s feelings. Interventions to enhance use of these reflections can be compared to usual care.

A further limitation of the RCTs in this review is the overall low quality ratings according to the guidelines from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Only nine studies were rated low in risk of bias with strong methodology, eight of which were successful in implementing randomization and allocation concealment together. As new RCTs of genetic counseling are designed, attention to rigorous methods is essential to enhancing the reliability of the evidence generated.

A highlight of this review is the innovation in genetic counseling research as evidenced by the RCT conducted by Eijzenga et al. (2014). In this RCT clients referred for cancer genetic counseling completed a pre-counseling questionnaire that was randomly shared with half of the genetic counselors. Access to the questionnaire led the genetic counselors to more frequently initiate discussion of topics important to the client and to clients having lower levels of cancer worries and psychological distress four weeks later. The intervention allowed the counselors to reflect on client needs prior to the counseling sessions and use the information to initiate a discussion that resulted in greater psychological wellbeing for the clients. The novelty of a small intervention resulting in significant client benefit suggests that other small systematic changes to genetic counseling interactions may also result in benefit for clients without extending the length of sessions. This study paves the way for future RCTs aimed at introducing theoretically based interventions to enhance practice.

Conclusion

Overall, RCTs from the past 25 years investigating genetic counseling outcomes provide emerging evidence for the effective use of telephone counseling and online resources in the cancer setting. They illustrate a number of counseling interventions that need further evaluation in additional contexts, but hold promise for enhancing the effectiveness of genetic counseling in meeting clients’ needs. Specifically, improvements in theoretical research design, attention to risk of bias and quality parameters, and consistent use of valid and reliable measures of outcomes such as psychological wellbeing, risk assessment, and knowledge, and further use of patient outcomes such as effective coping, and adaptation will promote evidence-based advancements in genetic counseling practice.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health. The authors thank NIH librarian Barbara Brandys for executing the literature searches and Dr. Gillian Hooker for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10897-017-0082-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

As an example, the search query utilized for PubMed was: “(“Genetic Counseling”[MeSH] OR ((“Genetic Testing”[MeSH] OR “Genetic Counseling”[tiab] OR “Genetic Counselling”[tiab] OR “Genetic Testing”[tiab]) AND (educati*[tiab] OR information[tiab] OR informing[tiab] OR “Counseling”[Mesh] OR Counsel*[tiab] OR consultation*[tiab] OR randomized[tiab]))) AND (Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Multicenter Study[ptyp] OR Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp] OR Controlled Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Evaluation Studies[ptyp] OR Patient Education Handout[ptyp] OR “Clinical Trials as Topic”[Mesh] OR randomized[tiab])”

Conflict of Interest Barbara A. Athens has no conflict of interest to declare. Samantha L. Caldwell has no conflict of interest to declare. Kendall L. Umstead has no conflict of interest to declare. Philip D. Connors has no conflict of interest to declare. Ethan Brenna has no conflict of interest to declare. Barbara B. Biesecker has no conflict of interest to declare.

Human Subjects No human studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Animal Subjects No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

References

- Albada A, van Dulmen S, Spreeuwenberg P, & Ausems MG (2015). Follow-up effects of a tailored pre-counseling website with question prompt in breast cancer genetic counseling. Patient Education and Counseling, 98, 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton S (2000). Which clinical studies provide the best evidence? The best RCT still trumps the best observational study. The BMJ, 321, 255–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett P, Phelps C, Brain K, Hood K, & Gray J (2007). A randomized controlled trial of a brief self-help coping intervention designed to reduce distress when awaiting genetic risk information. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63, 59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt BA, Biesecker BB, & Mastromarino CL (2000). Goals, benefits, and outcomes of genetic counseling: Client and genetic counselor assessment. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 94(3), 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesecker BB (2001). Goals of genetic counseling. Clinical Genetics, 60, 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, & Powers D (2010). Effects of a mail and telephone intervention on breast health behaviors. Health Education & Behavior, 37, 479–489. doi: 10.1177/1090198109348463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Burke W, Yasui Y, McTiernan A, & McLeran D (2002). Effects of risk counseling on interest in breast cancer genetic testing for lower risk women. Genetics in Medicine, 4(5), 359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Burke W, McTiernan A, Yasui Y, & Andersen MR (2004). Breast cancer risk counseling improves women’s functioning. Patient Education and Counseling, 53, 79–86. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Burke W, Culver JO, Press N, & Crystal S (2006). Effects of counseling Ashkenazi Jewish women about breast cancer risk. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12, 45–56. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain K, Gray J, Norman P, France E, Anglim C, Barton G, et al. (2000). Randomized trial of a specialist genetic assessment service for familial breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 92, 1345–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain K, Sivell S, Bennert K, Howell L, France L, Jordan S, et al. (2005). An exploratory comparison of genetic counselling protocols for HNPCC predictive testing. Clinical Genetics, 68, 255–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite D, Sutton S, Mackay J, Stein J, & Emery J (2005). Development of a risk assessment tool for women with a family history of breast cancer. Cancer Detection and Prevention, 29, 433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan AH, Datta SK, Skinner CS, Hollowell GP, Beresford HF, Freeland T, et al. (2015). Randomized trial of telegenetics vs. in-person cancer genetic counseling: Cost, patient satisfaction and attendance. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 24, 961–970. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9836-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butrick M, Kelly S, Peshkin BN, Luta G, Nusbaum R, Hooker GW, et al. (2015). Disparities in uptake of BRCA1/2 genetic testing in a randomized trial of telephone counseling. Genetics in Medicine, 17, 467–475. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzone KA, Prindiville SA, Jourkiv O, Jenkins J, DeCarvalho M, Wallerstedt DB, et al. (2005). Randomized comparison of group versus individual genetic education and counseling for familial breast and/or ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 3455–3464. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron LD, Biesecker BB, Peters E, Taber JM, & Klein WMP (2017). Self-regulation principles underlying risk perception and decision making within the context of genomic testing. Social and Personality Psychology Compass (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani C, Perobelli S, Bianchi V, Seia M, Melotti P, Zanolla L, et al. (2011). An interactive computer program can effectively educate potential users of cystic fibrosis carrier tests. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 155a, 778–785. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles S, Kessler L, Stopfer JE, Domchek S, & Halbert CH (2006). Satisfaction with genetic counseling for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among African American women. Patient Education and Counseling, 63, 196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijzenga W, Aaronson NK, Hahn DE, Sidharta GN, Van der Kolk LE, Velthuizen ME, et al. (2014). Effect of routine assessment of specific psychosocial problems on personalized communication, counselors’ awareness, and distress levels in cancer genetic counseling practice: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32, 2998–3004. doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.55.4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijzenga W, Bleiker EM, Ausems MG, Sidharta GN, Van der Kolk LE, Velthuizen ME, et al. (2015). Routine assessment of psychosocial problems after cancer genetic counseling: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Genetics, 87, 419–427. doi: 10.1111/cge.12473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, & Ubel PA (2011). Helping patients decide: Ten steps to better risk communication. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 103, 1436–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Steffen AD, & Taglialatela LA (2007). Effects of colon cancer risk counseling for first-degree relatives. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 16, 1485–1491. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-06-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves KD, Wenzel L, Schwartz MD, Luta G, Wileyto P, Narod S, et al. (2010). Randomized controlled trial of a psychosocial telephone counseling intervention in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 19, 648–654. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-09-0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Biesecker BB, McInerney AM, Mauger D, & Fost N (2001a). An interactive computer program can effectively educate patients about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 103, 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, McInerney AM, Biesecker BB, & Fost N (2001b). Education about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: Patient preferences for a computer program or genetic counselor. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 103, 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW, Harper GR, Friedman LC, Rubinstein WS, et al. (2004). Effect of a computer-based decision aid on knowledge, perceptions, and intentions about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292, 442–452. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW, Friedman LC, Harper GR, Rubinstein WS, et al. (2005). Use of an educational computer program before genetic counseling for breast cancer susceptibility: Effects on duration and content of counseling sessions. Genetics in Medicine, 7, 221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RC, Christensen KD, Cupples LA, Relkin NR, Whitehouse PJ, Royal CD, et al. (2014). A randomized noninferiority trial of condensed protocols for genetic risk disclosure of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 11, 1222–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga SB, Barry WT, Mills R, Svetkey L, Suchindran S, Willard HF, et al. (2014). Impact of delivery models on understanding genomic risk for type 2 diabetes. Public Health Genomics, 17, 95–104. doi: 10.1159/000358413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert CH, Kessler L, Troxel AB, Stopfer JE, & Domchek S (2010). Effect of genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in African American women: A randomized trial. Public Health Genomics, 13, 440–448. doi: 10.1159/000293990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanprasertpong T, Rattanaprueksachart R, Janwadee S, Geater A, Kor-anantakul O, Suwanrath C, et al. (2013). Comparison of the effectiveness of different counseling methods before second trimester genetic amniocentesis in Thailand. Prenatal Diagnosis, 33, 1189–1193. doi: 10.1002/pd.4222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmes AW, Culver JO, & Bowen DJ (2006). Results of a randomized study of telephone versus in-person breast cancer risk counseling. Patient Education and Counseling, 64, 96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneman L, Oosterwijk JC, van Asperen CJ, Menko FH, Ockhuysen-Vermey CF, Kostense PJ, et al. (2013). The effectiveness of a graphical presentation in addition to a frequency format in the context of familial breast cancer risk communication: A multicenter controlled trial. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13, 55. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, & Green S (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 5.1.0 (updated March 2011): The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- Hodgson J, Metcalfe S, Gaff C, Donath S, Delatycki MB, Winship I, et al. (2015). Outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of a complex genetic counselling intervention to improve family communication. European Journal of Human Genetics, 24, 356–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker GW, Leventhal KG, DeMarco T, Peshkin BN, Finch C, Wahl E, et al. (2011). Longitudinal changes in patient distress following interactive decision aid use among BRCA1/2 carriers: A randomized trial. Medical Decision Making, 31, 412–421. doi:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AG, Cappelli M, Humphreys L, Allanson JE, Chiu TT, Peeters C, et al. (2005). A randomized trial comparing alternative approaches to prenatal diagnosis counseling in advanced maternal age patients. Clinical Genetics, 67, 303–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa HL, Huang LH, Hsieh FJ, & Chow SN (2010). Informed consent for antenatal serum screening for down syndrome. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 49, 50–56. doi: 10.1016/s1028-4559(10)60009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J, Calzone KA, Dimond E, Liewehr DJ, Steinberg SM, Jourkiv O, et al. (2007). Randomized comparison of phone versus in-person BRCA1/2 predisposition genetic test result disclosure counseling. Genetics in Medicine, 9, 487–495. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31812e6220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney AY, Butler KM, Schwartz MD, Mandelblatt JS, Boucher KM, Pappas LM, et al. (2014). Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: A cluster randomized trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson A, Harvey G, & McCormack B (1998). Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. Quality in Health Care, 7, 149–158. doi: 10.1136/qshc.7.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppermann M, Pena S, Bishop JT, Nakagawa S, Gregorich SE, Sit A, et al. (2014). Effect of enhanced information, values clarification, and removal of financial barriers on use of prenatal genetic testing: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 312, 1210–1217. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Biesecker B, Benkendorf JL, Kerner J, Gomez-Caminero A, Hughes C, et al. (1997). Controlled trial of pretest education approaches to enhance informed decision-making for BRCA1 gene testing. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 89, 148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Hughes C, Benkendorf JL, Biesecker B, Kerner J, Willison J, et al. (1999). Racial differences in testing motivation and psychological distress following pretest education for BRCA1 gene testing. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 8, 361–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery JT, Horick N, Kinney AY, Finkelstein DM, Garrett K, Haile RW, et al. (2014). A randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in members of high-risk families in the colorectal cancer family registry and cancer genetics network. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 23, 601–610. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-13-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloff ET, Moyer A, Shannon KM, Niendorf KB, & Col NF (2006). Healthy women with a family history of breast cancer: Impact of a tailored genetic counseling intervention on risk perception, knowledge, and menopausal therapy decision making. Journal of Women’s Health, 15, 843–856. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister M, Wood AM, Dunn G, Shiloh S, & Todd C (2011). The genetic counseling outcome scale: A new patient-reported outcome measure for clinical genetics services. Clinical Genetics, 79(5), 413–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInerney-Leo A, Biesecker BB, Hadley DW, Kase RG, Giambarresi TR, Johnson E, et al. (2004). BRCA1/2 testing in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families: Effectiveness of problem-solving training as a counseling intervention. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 130a, 221–227. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedzybrodzka ZH, Hall MH, Mollison J, Templeton A, Russell IT, Dean JC, et al. (1995). Antenatal screening for carriers of cystic fibrosis: Randomised trial of stepwise v couple screening. The BMJ, 310, 353–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM, Roussi P, Daly MB, Buzaglo JS, Sherman K, Godwin AK, et al. (2005). Enhanced counseling for women undergoing BRCA1/2 testing: Impact on subsequent decision making about risk reduction behaviors. Health Education & Behavior, 32, 654–667. doi: 10.1177/1090198105278758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SV, Barsevick AM, Egleston BL, Bingler R, Ruth K, Miller SM, et al. (2013). Preparing individuals to communicate genetic test results to their relatives: Report of a randomized control trial. Familial Cancer, 12, 537–546. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9609-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishigaki M, Tokunaga-Nakawatase Y, Nishida J, & Kazuma K (2014). The effect of genetic counseling for adult offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes on attitudes toward diabetes and its heredity: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 23, 762–769. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platten U, Rantala J, Lindblom A, Brandberg Y, Lindgren G, & Arver B (2012). The use of telephone in genetic counseling versus in-person counseling: A randomized study on counselees’ outcome. Familial Cancer, 11, 371–379. doi: 10.1007/s10689-012-9522-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redlinger-Grosse K, Veach PM, Cohen S, LeRoy BS, MacFarlane IM, & Zierhut H (2016). Defining our clinical practice: The identification of genetic counseling outcomes utilizing the reciprocal engagement model. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 25(2), 239–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JS, Chen CA, Uhlmann WR, & Green RC (2012). Effectiveness of a condensed protocol for disclosing APOE genotype and providing risk education for Alzheimer disease. Genetics in Medicine, 14, 742–748. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roshanai AH, Rosenquist R, Lampic C, & Nordin K (2009). Does enhanced information at cancer genetic counseling improve counselees’ knowledge, risk perception, satisfaction and negotiation of information to at-risk relatives? A randomized study. Acta Oncologica, 48, 999–1009. doi: 10.1080/02841860903104137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussi P, Sherman KA, Miller S, Buzaglo J, Daly M, Taylor A, et al. (2010). Enhanced counselling for women undergoing BRCA1/2 testing: Impact on knowledge and psychological distress-results from a randomised clinical trial. Psychology & Health, 25, 401–415. doi: 10.1080/08870440802660884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, Benkendorf J, Lerman C, Isaacs C, Ryan-Robertson A, & Johnson L (2001). Impact of educational print materials on knowledge, attitudes, and interest in BRCA1/BRCA2: Testing among Ashkenazi Jewish women. Cancer, 92, 932–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, DeMarco TA, Peshkin BN, Lawrence W, Rispoli J, et al. (2009). Randomized trial of a decision aid for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: Impact on measures of decision making and satisfaction. Health Psychology, 28, 11–19. doi: 10.1037/a0013147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, Mandelblatt J, Nusbaum R, Huang AT, et al. (2014). Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32, 618–626. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.51.3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibbald B, & Roland M (1998). Understanding controlled trials. Why are randomised controlled trials important? The BMJ, 316, 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temme R, Gruber A, Johnson M, Read L, Lu Y, & McNamara J (2015). Assessment of parental understanding of positive newborn screening results and carrier status for cystic fibrosis with the use of a short educational video. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 24, 473–481. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L, & Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. (2003). Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine, 28(12), 1290–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorwinden JS, Jaspers JP, ter Beest JG, Kievit Y, Sijmons RH, & Oosterwijk JC (2012). The introduction of a choice to learn pre-symptomatic DNA test results for BRCA or lynch syndrome either face-to-face or by letter. Clinical Genetics, 81, 421–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]