Abstract

Objective

To collate the evidence on the accuracy parameters of all available diagnostic methods for detecting SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

A systematic review with meta-analysis was performed. Searches were conducted in Pubmed and Scopus (April 2020). Studies reporting data on sensitivity or specificity of diagnostic tests for COVID-19 using any human biological sample were included.

Results

Sixteen studies were evaluated. Meta-analysis showed that computed tomography has high sensitivity (91.9% [89.8%-93.7%]), but low specificity (25.1% [21.0%-29.5%]). The combination of IgM and IgG antibodies demonstrated promising results for both parameters (84.5% [82.2%-86.6%]; 91.6% [86.0%-95.4%], respectively). For RT-PCR tests, rectal stools/swab, urine, and plasma were less sensitive while sputum (97.2% [90.3%-99.7%]) presented higher sensitivity for detecting the virus.

Conclusions

RT-PCR remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of COVID-19 in sputum samples. However, the combination of different diagnostic tests is highly recommended to achieve adequate sensitivity and specificity.

Key Words: SARS-CoV-2, Coronavirus, Evidence, Sensitivity, Specificity

INTRODUCTION

After the first case reports of an acute respiratory syndrome of unknown etiology in the city of Wuhan, Hubei province (December 31, 2019), Chinese authorities identified a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) that causes the clinical disease COVID-19. The virus outbreak spread quickly, significantly affecting all continents with more than 2 million people infected and thousands of deaths.1 , 2 Consequently, nations are facing the overwhelming of health care systems and both psychological and economic burdens. The lack of effective treatments or prevention strategies has contributed toward the increase in the number of cases, enhancing health care expenses with hospitalizations and palliative therapies. Additionally, there are limited diagnostic tests available, which favors the growth of under-reporting of cases.2 , 3

Patients report fever and cough, and most develop chest discomfort, difficulty in breathing or pneumonia, being clinically diagnosed by imaging tests such as chest X-ray or computed tomography (CT). CT equipment is widespread worldwide and the scan process is relatively simples and quick, which enables rapid screening for suspected patients. The typical findings of chest CT images for individuals with COVID-19 are multifocal bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities or consolidation with interlobular septal and vascular thickening in the peripheral areas of the lungs. However, CT findings can change as the disease progresses and these manifestations may also be compatible with other viral pneumonias.4 , 5

In this context, the current gold standard for diagnosing COVID-19 is based on a molecular test of the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), aimed at detecting the RNA of the virus in respiratory samples such as nasopharyngeal swabs or bronchial aspirate.6 The real-time RT-PCR test provides a sensitive (the ability of the test to correctly identify those patients with the disease 7 , 8) and specific (the ability of the test to correctly identify those patients without the disease 8) method to detect SARS-COV-2, with different diagnosis protocols including sequences of target primers available in the World Health Organization public database.6 , 9 However, researchers should be aware that this test can also give false negatives if the amount of viral genoma is insufficient or if the correct time-window of viral replication is missed.10 Although the COVID-19 incubation period is estimated to be 5 days, false negative results are common within 7 days of infection. Additionally, RT-PCR process is time-consuming and shortages in test kit supplies are common worldwide—especially during the beginning of the epidemic outbreak.11

Other simpler and rapid methods, such as serological testing of IgM and IgG production in response to viral infection, can be used to enhance the detection sensitivity and accuracy of the molecular test or for screening purposes to assess antibody profiles in a large population.12 , 13 Because antibodies are usually detected only 1-3 weeks after the onset of symptoms, these tests are used to assess the overall infection rate in the community—including the rate of asymptomatic infections—or in remote areas where qPCR assays are not available.12 , 14

In this scenario, given the limitations of clinical diagnosis alone (due to the similarity of the symptoms of COVID-19 infection with those of other viruses) and the availability of different molecular and serological tests with both technical advantages and disadvantages, it is important to summarize the accuracy parameters of these methods and investigate whether they are sufficiently specific or sensitive to fit their role in practice. Few studies addressing the diagnostic performance of tests for COVID-19 exist, with special focus only on commercially assays available in a given country. In addition, according to the different health care settings worldwide, different patterns on testing may exist. For instance, the number of daily tests performed per thousand people in Australia or in the United States is around 1.80, while in Europe is near 1.06 and in South America is lower 0.30 (https://ourworldindata.org/).

Thus, we aimed to perform a systematic review with meta-analysis to gather evidence on the features of all available diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2, including parameters of sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios and summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curves, whenever possible.

METHODS

This study was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies (PRISMA-DTA) statement and Cochrane Collaboration recommendations.15 , 16

Search strategy

Systematic searches were conducted in Pubmed and Scopus without limits of time-frame or language (last updated April 2020). The search strategy included the following descriptors: “diagnostic,” “test,” “assay,” “covid-19,” “sars-cov-2”and other terms combined with Boolean operators AND and OR. The complete strategy is available in the supplementary material. Manual searches in the references lists of included studies and in the gray literature (eg, Google Scholar) were also performed.

Eligibility criteria

Titles and abstracts of retrieved articles were screened for eligibility. Relevant articles were read in full and those fulfilling inclusion criteria had their data extracted. Two authors performed all the literature selection steps individually and then discussed the differences with a third author.

Studies were included in this systematic review if they met all the following eligibility criteria: (i) evaluation of any diagnostic method; (ii) aimed at diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19); (iii) using any human biological sample; and (iv) reporting data on the accuracy of the test (eg, sensitivity and/or specificity). We excluded studies published in non-Roman characters.

Data extraction and bias assessment

The following data were independently extracted by 2 researchers: general study details (authors, year of publication, country of origin, study design, and sample size), methods, characteristics, and diagnostic test results (true positive, TP; true negative, TN; false positive, FP; false negative, FN, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy).

Two reviewers evaluated independently the risk of bias in each study using the Diagnostic Precision Study Quality Assessment Tool (QUADAS-2) recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. The assessment was performed using the Review Manager Software version 5.3 17

Statistical analyses

The meta-analyses were performed according to the technique and type of sample from each study (ie, by subgroups). Sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR) and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) were measured with a 95% confidence interval based on the TP, TN, FP, and FN rates that were extracted from the included studies.

Sensitivity, defined as the probability that a test result will be positive when the disease exists (true positive rate) was calculated as = VP/(VP + FN). Specificity, defined as the probability that a test result will be negative when the disease is not present (true negative rate) was calculated as = VN/(VN + VP). The PLR is the ratio between the probability of a positive test result given the presence of the disease and the probability of a positive test result given the absence of the disease, that is = true positive rate/false positive rate, or expressed as sensitivity/(1-specificity). The NLR is ratio between the probability of a negative test result given the presence of the disease and the probability of a negative test result given the absence of the disease, that is = false negative rate/true negative rate, or expressed as (1-sensitivity)/specificity.

SROC curves based on TP e FP rates were also built whenever possible to describe the relationship between test sensitivity and specificity. An area under the curve (AUC) close to 1 indicated a good diagnostic performance of the test. All analyses were performed using the Meta-Disc© version 1.4.7.

The heterogeneity of the studies was established by χ2 analysis, with inconsistency values (I2) greater than 50% being considered as moderate heterogeneity, and I2 greater than 75% defined as high heterogeneity. Outcomes with I2 values greater than 50% were submitted to sensitivity analysis (ie, hypothetical removal of studies).

RESULTS

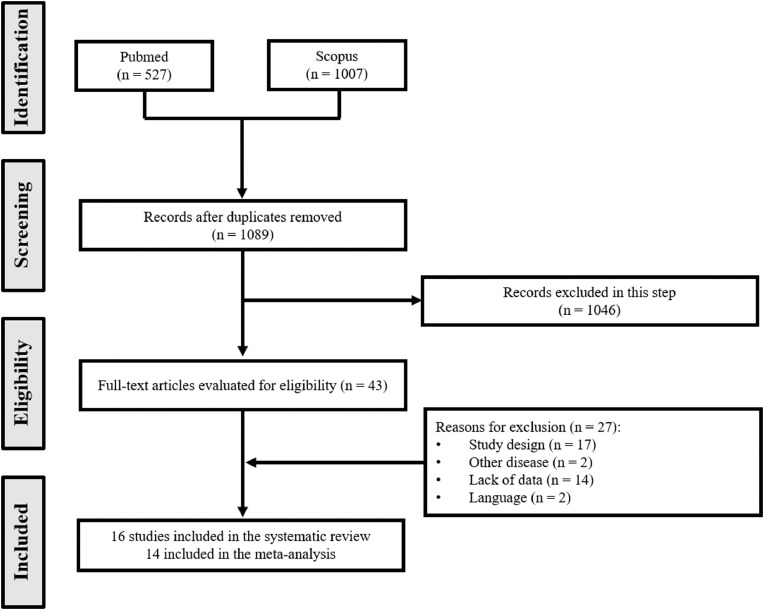

A total of 1,089 articles were identified after duplicate removal. Of these, 1,046 were excluded during the screening phase (title and abstract reading), with 43 records being fully appraised. Sixteen studies were included finally in the systematic review.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 We were able to include 14 trials in the quantitative analyses (meta-analysis): the studies by Corman et al. 22 and Pfefferle et al. 33 did not address the clinical application of the methods (Fig 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of included studies.

All studies included in this review (n = 2,297 patients) were published in 2020, designed as retrospective observational cohorts, with only one defined as a control-case study.32 Fourteen studies were conducted in China,18, 19, 20 , 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 while Italy, 21 Netherlands,22 England,22 and Germany 33 contributed with one study each.

All studies presented a test group (patients diagnosed with COVID-19), while only 6 trials used a control group (patients negative for COVID-19 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 33). Patients from the test group were previously diagnosed using the (gold standard) PCR technique. The diagnostic methods were tested for the following samples: nasopharyngeal swab,20 , 30 , 32 nasopharyngeal aspirate,20 throat swab,20 , 26 , 30 , 32 blood,21 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 32 saliva,20 , 27 sputum,20 , 30 urine,20 , 27 , 28 , 30 and stool and rectal swabs.20 , 27 , 28 , 31 Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Country | No. of patients/ samples |

No. of control group patients/ samples |

Reference method (gene) | Evaluated method | Sample type |

Marker/gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ai, 2020 18 |

China | 1,014 | 413 | RT-PCR (ORF1ab; N) | Chest CT | Chest image | - |

| Long, 2020 19 |

China | 36 | - | RT-PCR | Chest CT | Chest image | - |

| Cassaniti, 2020 21 | Italy | 50 | 60 | RT-PCR (RdRp and E) | LFIA | Whole blood | IgM/IgG |

| Chan, 2020 20 |

China | 15/273 | 39 | RT-PCR (RdRp-P2) | RT-PCR | Naso-pharyngeal aspirate | Hel |

| Naso-pharyngeal swab | |||||||

| Throat swab | |||||||

| Saliva | S | ||||||

| Sputum | |||||||

| Plasma | |||||||

| Urine | N | ||||||

| Feces | |||||||

| Rectal swab | |||||||

| Corman, 2020 22 | Nether-lands England China |

-* | -* | RT-PCR (RdRp) | RT-PCR | Sputum | RdRp and E |

| Nose swab | |||||||

| Throat swab | |||||||

| Fecal | |||||||

| In vitro specific transcribed RNA standards | |||||||

| SARS-CoV genomic RNA from cell culture | |||||||

| Li, 2020a 23 |

China | 78 | - | RT-PCR (E) | Chest CT | Chest image | - |

| Li, 2020b 24 |

China | 404 | 131 | RT-PCR | LFIA | Whole blood or plasma (fingerstick or venous) | IgM/IgG |

| Liu, 2020 25 |

China | 214 | 128 | RT-PCR | ELISA | Serum | IgM/IgG |

| Pan, 2020 26 |

China | 23 | - | RT-PCR or virus gene sequence highly homologous to SARS-CoV-2 | RT-PCR | Throat swabs | NR |

| Stool | |||||||

| Sputum | |||||||

| Pfefferle, 2020 33 | Germany | -* | 110* | - | RT-PCR | Swab | E |

|

In vitro transcribed RNA of the E gene of SARS-CoV-2 | |||||||

| Purified RNA of SARS-CoV (strain Frankfurt-1) | |||||||

| To, 2020 27 |

China | 23 | - | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | Saliva | Hel |

| Blood | |||||||

| Rectal swab | |||||||

| Urine | |||||||

| - | |||||||

| EIA | Serum | IgM/IgG | |||||

| Xie, 2020 28 |

China | 19 | - | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | Throat swab | - |

| Stool | |||||||

| Blood | |||||||

| Urine | |||||||

| Chest CT | Chest image | - | |||||

| Xu, 2020 29 |

China | 90 | - | RT-PCR | Chest CT | Chest image | - |

| Yu, 2020 30 |

China | 76 | - | NR | ddPCR and RT-PCR | Nasal swab | ORF1ab and N |

| Throat swab | |||||||

| Sputum | |||||||

| Urine | |||||||

| Blood | |||||||

| Zhang, 2020 31 |

China | 14 | - | RT-PCR | NAT | Stool | - |

| Oropharyngeal swab | |||||||

| Chest CT | Chest image | - | |||||

| Zhao, 2020 32 |

China | 173/535 | - | RT-PCR | ELISA | Plasma | IgM/IgG |

E, envelope protein gene; ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; Hel, helicase protein gene; LFIA, lateral flow immunoassay; N, nucleocapsid protein gene; NAT, nucleic acid tests; NR, not reported; ORF1ab, open reading frame 1ab gene; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene for SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and bat-SARS-related CoV; RdRp-P2, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase specific gene for SARS-CoV-2; RT-PCR, real‐time reverse‐transcriptase polymerase‐chain reaction; S, spike protein gene.

Samples were used only for the validation of the method (no clinical application).

Analytical parameters

Three studies evaluated the optimization of PCR parameters for the detection of SARS-CoV-2.20 , 22 , 33 Chan et al. 20 developed and compared the performance of 3 new essays of RT-PCR of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp)/helicase (Hel), spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) genes from SARS-CoV-2. Corman et al. 22 assessed several SARS-related viral genomic sequences to design the best primer and probe set. Pferfferle et al. 33 investigated a set of primer and probes, targeting the E gene, for use in an automated system (Cobas 6800 System; see Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Analytical parameters reported by the included studies

| Study | Method | Probe RNA | Gene target | LoD RNA copies/reaction (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan, 2020 20 |

RT-PCR | specific for SARS-CoV | RdRp/Helicase | 11.2 (7.2-52.6) |

| RT-PCR | specific for SARS-CoV | Spike gene | NA | |

| RT-PCR | specific for SARS-CoV | N gene | 21.3 (11.6-177.0) | |

| RT-PCR | specific for SARS-CoV-2 | RdRp gene | NA | |

| Corman, 2020 22 | RT-PCR (new method) |

specific for SARS-CoV | E gene | 5.2 (3.7-9.6) |

| RT-PCR (new method) |

specific for SARS-CoV | RdRp gene | 3.8 (2.7-7.6) | |

| RT-PCR TaqMan Fast | specific for SARS-CoV | E gene | 3.2 (2.2-6.8) | |

| RT-PCR TaqMan Fast | specific for SARS-CoV | RdRp gene | 3.7 (2.8-8.0) | |

| RT-PCR (new method) |

specific for SARS-CoV-2 | E gene | 3.9 (2.8-9.8) | |

| RT-PCR (new method) |

specific for SARS-CoV-2 | RdRp gene | 3.6 (2.7-11.2) | |

| Pfefferle, 2020 33 |

RT-PCR | specific for SARS-CoV-2 | E gene | 275.72 (NR) |

CI, confidence interval 95%; LoD, limit of detection; NA, not applied; NR, unreported.

The genes E and RdRp were the most commonly used to detect the COVID-19 virus, both with high analytical sensitivity (technical limit of detection of 3.2 and 3.6 copies per reaction, respectively). The detection of the gene N presented lower analytical sensitivity (8.3 copies per reaction). The probe used by these studies is indicated for any SARS-CoV infection, including SARS-CoV-2. Process automation by using the open channel of the Cobas 6800 systems significantly increased the limit of detection.

Diagnostic accuracy of tests

Meta-analyses evaluating the parameters of accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, PLR and NLR) of the reported tests were performed (Supplementary Table S1), results are shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of the parameters of accuracy for the different diagnostic techniques

| Technique | Sample | No. of studies | Sensitivity (95% CI) |

Specificity (95% CI) |

PLR (95% CI) |

NLR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computed tomography | - | 6 18,19,23,28,29,31 | 0.919 (0.898-0.937) I2 = 92.9% |

0.251 (0.210-0.295) I2 = 32.8% |

1.194 (0.936-1.525) I2 = 56.2% |

0.301 (0.043-2.124) I2 = 71.9% |

| Immunological test (IgM and IgG) |

Blood, serum, plasma | 4 21,24,25,32 | 0.845 (0.822-0.866) I2 = 93.2% |

0.916 (0.860-0.954) I2 = 0.0% |

7.604 (3.903-14.817) I2 = 12.8% |

0.170 (0.041-0.697) I2 = 97.0% |

| Immunological test (IgM and IgG) |

Blood | 3 21,24,32 | 0.863 (0.833-0.888) I2 = 96.3% |

0.907 (0.848-0.948) I2 = 0.0% |

8.618 (5.219-14.231) I2 = 0.0% |

0.146 (0.021-1.028) I2 = 99.0% |

| Immunological test (IgM and IgG) |

Serum | 2 24,25 | 0.82 (0.78-0.85) I2 = 35.8% |

- | - | - |

| Immunological test (IgM) | Blood, serum, plasma | 5 21,24,25,27,32 | 0.770 (0.745-0.795) I2 = 89.9% |

0.933 (0.886-0.965) I2 = 18.5% |

7.295 (3.403-15.641) I2 = 96.1% |

0.211 (0.067-0.666) I2 = 96.1% |

| Immunological test (IgM) | Blood | 3 21,24,32 | 0.788 (0.754-0.819) I2 = 94.8% |

0.931 (0.882-0.964) I2 = 43.3% |

8.390 (3.367-20.905) I2 = 24.0% |

0.274 (0.072-1.043) I2 = 98.0% |

| Immunological test (IgM) | Serum | 3 24,25,27 | 0.743 (0.701-0.782) I2 = 73.1% |

- | - | - |

| Immunological test (IgG) | Blood, serum, plasma | 5 21,24,25,27,32 | 0.694 (0.666-0.721) I2 = 90.9% |

0.694 (0.666-0.721) I2 = 0% |

25.626 (7.131-92.087) I2 = 18.0% |

0.378 (0.128-1.111) I2 = 98.6% |

| Immunological test (IgG) | Blood | 3 21,24,32 | 0.661 (0.623-0.698) I2 = 94.5% |

0.988 (0.958-0.999) I2 = 0.0 |

26.981 (6.240-116.655) I2- 27.3% |

0.377 (0.128-1.113) I2 = 98.6% |

| Immunological test (IgG) | Serum | 2 25,27 | 0.739 (0.696-0.779) I2 = 80.7% |

- | - | - |

| PCR | Stool, feces, rectal swabs | 4 20,27,30,31 | 0.241 (0.167-0.330) I2 = 82.6% |

- | - | - |

| PCR | Urine | 4 20,27,28,30 | 0.000 (0.000-0.037) I2 = 0.0% |

- | - | - |

| PCR | Blood | 3 21,27,28 | 0.073 (0.041-0.117) I2 = 85.9% |

- | - | - |

| PCR | Nasopharyngeal aspirate, nasopharyngeal and throat swab | 4 20,26,30,32 | 0.733 (0.681-0.780) I2 = 87.5% |

- | - | - |

| PCR | Sputum | 2 20,30 | 0.972 (0.903-0.997) I2 = 48.3% |

- | - | - |

| PCR | Saliva | 2 20,27 | 0.623 (0.545-0.696) I2 = 92.2% |

- | - | - |

CI, confidence interval; I2, inconsistency; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction; PLR, positive likelihood ratio.

Data on CT of the chest was reported by 6 trials.18 , 19 , 23 , 28 , 29 , 31 Meta-analysis showed this method to be sensitive (91.9%, 95% CI 89.8%-93.7%; heterogeneity between trials of I2 = 92.9%), however with low specificity (25.1%, 95% CI 21.0%-29.5%, I2 = 32.8%; see Figure S1 of the supplementary material for complete results).

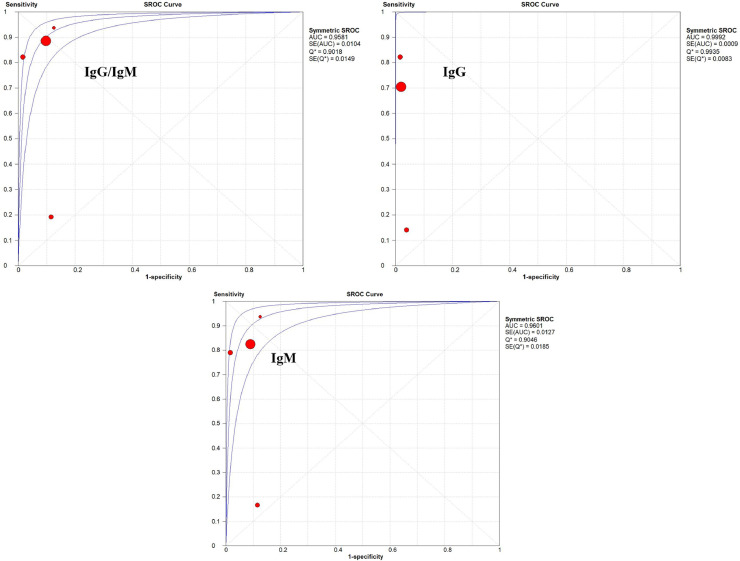

Immunological tests (IgM and IgG) were evaluated in 5 trials as a diagnostic method for COVID-19.21 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 32 The antibody dosage was tested in whole blood samples,21 , 32 fingerstick blood,24 serum,24 , 25 , 27 and plasma.24 Overall, sensitivity and specificity were higher when the combination of IgM and IgG antibodies was evaluated (see Supplementary Figs S2, S3, and S4), reaching 84.5% (95% CI 82.2%-86.6%, I2 = 93.2%) and 91.6% (95% CI 86.0%-95.4%, I2 = 0%) respectively. The SROC curves for the immunological diagnostic tests are shown in Figure 2 .

Fig. 2.

SROC curves obtained for immunological tests.

Seven studies addressed the diagnostic test by PCR.20 , 26, 27, 28 , 30, 31, 32 Meta-analyses were conducted according to the type of sample. Rectal stool/swab (24.1%, 95% CI 16.7%-33.0%), urine (0.0%, 95% CI 0.0%-3.7%), plasma (7.3%, 95% CI 4.1%-11.7%) were less sensitive for detection of COVID-19. Sputum (97.2%, 95% CI 90.3%-99.7%), saliva (62.3%, 95% CI 54.5%-69.6%), nasopharyngeal aspirate/swab and throat swab (73.3%, 95% CI 68.1%-78.0%) were more sensitive for detecting the virus (Fig S5 in supplementary material). Due to the limited number of PCR studies with a control group, it was not possible to perform statistical analyses on the parameters of specificity, PLR and NLR. Only the studies by Xie et al. 28 and Yu et al. 30 tested the PCR method in a control group. In both trials, specificity was 100% for stool, urine, blood, nasal swab and throat swab samples, while throat swab and sputum samples had specificities of 98.6% and 90.0%, respectively (Table S2 in supplementary material). Sensitivity analyses were performed for all meta-analyses with high heterogeneity results (I2 > 50%); however, no additional differences were found compared to the effects of the original analyses (data not shown).

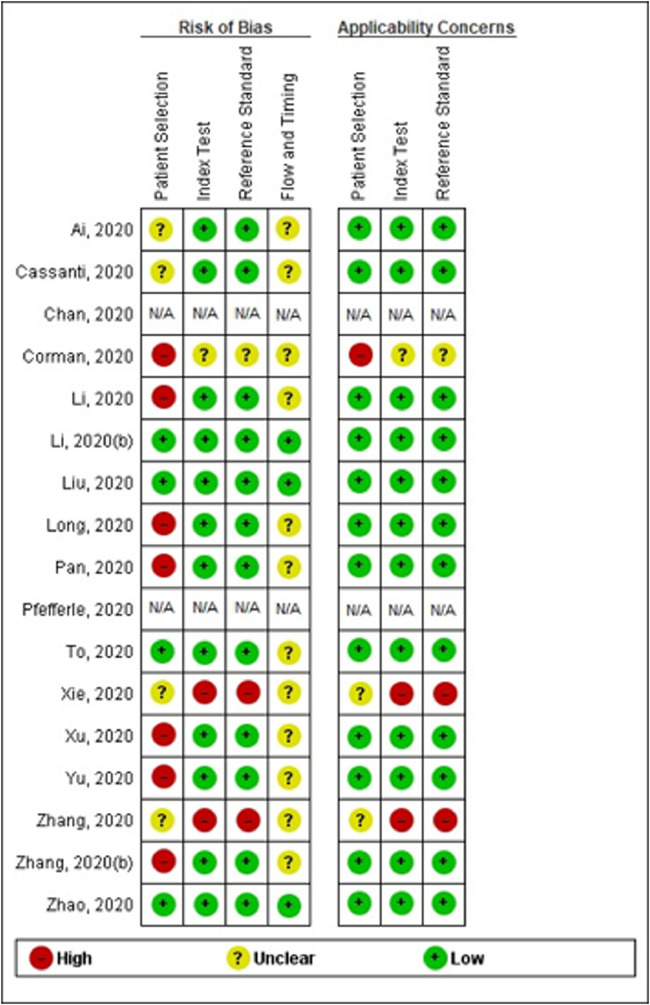

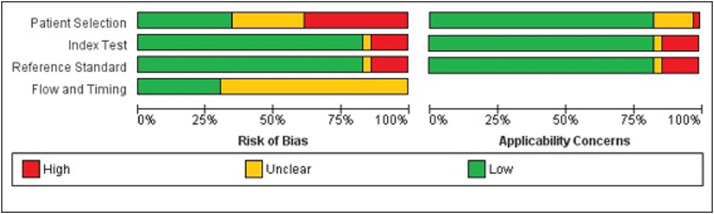

Quality assessment

Studies were rated as being of moderate overall methodological quality according to QUADAS-2 (see Fig. 3, Fig. 4 ). The studies by Chan et al. 20 and Pfefferle et al. (29) were not evaluated given the lack of clinical application of the tests (ie, only the analytical performance of the methods was assessed).

Fig. 3.

Methodological quality of the included studies (individual assessment).

Fig. 4.

Summary of the methodological quality of the included studies.

Around one-quarter of the trials (26%) did not describe the methods of patient selection, and almost half (46%) included previously diagnosed patients, which may enhance the risk of bias. However, the majority of the patients included matched the review question and were likely to be diagnosed with the evaluated tests (ie, no major concerns for the applicability domain). Overall, 80% of the studies properly reported both index and reference standard tests and how they were conducted and interpreted. Only 3 studies (20%) properly reported the interval between tests, whether patients received different index or standard assays, and the complete statistical analyses performed, thus being judged as having low risk of bias for the flow and timing domain. The remaining studies were classified as with an unclear risk of bias for this domain.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review with meta-analysis to collate the available evidence on the accuracy parameters of different diagnostic methods (clinical, molecular, and serological) for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different samples, including blood, nasopharyngeal swab, sputum, saliva, urine and feces. We were also able to evaluate qualitatively the main analytical parameters reported in the molecular techniques.

The development of new molecular techniques depends on the knowledge of the proteomic and genomic composition of the virus or of changes in the hosts’ protein expressions during and after infection.34 Genome sequencing is important for researchers to design primers and probes for PCR and other molecular tests. The SARS-CoV-2 virus has a single-stranded, positive RNA genome of approximately 30,000 nucleotides in length that encodes 27 proteins, including an RdRP and 4 structural proteins: surface glycoprotein (S), envelope protein (E), matrix protein (M) and nucleocapsid protein (N; 34 , 35. In the past months, different RT-PCR kits for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 have been developed, being able to amplify a small amount of viral genetic material in a sample.36 In this technique, the RNA of the virus is reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA strands (cDNA), whose specific regions are amplified. The process usually involves 2 main steps: sequence alignment and primer design, and assay optimization and testing, especially because this method requires several temperature changes for each cycle using thermocycling equipment.34

We found that in trials evaluating the RdRp/Hel gene, there were no cross-reactions with other pathogenic coronaviruses and human respiratory pathogens in cell culture or clinical samples. On the other hand, the specific SARS-CoV-2 (RdRp) gene reacted with SARS-CoV in cell culture.20 It is important to avoid the use of genes that could potentially cause false-negative results. Assays designed as 2-target systems, with a primer universally detecting several coronaviruses (including SARS-CoV-2), and a second set of primers specifically detecting SARS-CoV-2, are the most suitable to obtain lower LoDs.22 However, the use of different reagents, primer/probe concentrations, and cycling conditions may limit the sensitivity of the test.20 , 34 In this context, Pfefferle et al. 33 proposed an automated solution for molecular diagnosis, including the management of a large volume of samples. The system used in this study (Cobas 6800 System) fully automates the extraction, purification, amplification, and detection of nucleic acids. Nonetheless, the analytical performance of the method was lower compared to conventional techniques.20 , 22 This may arise partly from differences in the determination of LoD among studies. While in conventional methods the target RNA is added manually to the reagent mix for amplification, in automated systems the control (purified RNA) is inserted into the samples and passes through the entire workflow of the device, including extraction and purification.33

Our meta-analyses demonstrated that among all methods, the PCR technique using sputum samples was the most sensitive method for diagnosing COVID-19. In contrast, this same technique applied to other samples (eg, urine, blood, stool, feces, and rectal swabs) showed the worst sensitivity results. Considering that the nucleic acid test is the main diagnostic test for this infection,37 , 38 the choice of the type of sample is an important step for successful diagnosis. Comparison of the meta-analysis results from different clinical specimens clearly demonstrated that respiratory samples are the most suitable for achieving higher sensitivity rates. These results corroborate with the CDC recommendations, which state that initial tests for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 should prioritize the collection of respiratory samples.37 , 38 One aspect that should not be disregarded is the fact that the presence of the virus in the different biological samples is related to the period of collection, that is, to the clinical course of the disease. Yet, even at low concentrations these other specimens, as well as respiratory fluids, may be involved in the transmission of the disease. A recent study showed that SARS-CoV-2 may exist in children's gastrointestinal tract for a longer time than in the respiratory system.39

Our study also demonstrated that CT was the second most sensitive test. SARS-CoV-2 is known to infect primarily the respiratory system, causing inflammation, interstitial damage, changes in the parenchyma, and cell death.5 Thus, the manifestations in CT of the chest have been considered as a very important strategy for supplementary diagnosis in view of the limitations of other techniques, such as the case of false-negative results with RT-PCR.40 However, this method has low specificity and a low PLR compared to immunological tests, which may hamper its isolated use in clinical practice. This can be explained by the chest imaging findings being due to other viral infections.

Regarding immunological tests, higher sensitivity, specificity and better NLR were obtained when the total antibodies were evaluated. On the other hand, the best PLR result was presented by the IgG immunological test. The global assessment of the value of this diagnostic test also demonstrated it to have the highest AUC value in the SROC curve (0.9992, Q* = 0.9935). Nonetheless, both IgM alone and combined with IgG showed high AUC values (0.9601, Q* = 0.9046; 0.9581, Q* = 0.9018, respectively), similarly to what was reported by Castro et al.,41 indicating a high level of accuracy for immunological tests in the diagnosis of COVID-19. The antibodies researched in these tests refer to structural antigenic proteins of SARS-CoV-2, such as spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, which have been identified as the most relevant in the development of serological assays for the diagnosis of the infection.14 Usually, the body's immune response to a pathogen takes 1-2 weeks to occur. In this context, the use of serological tests for detection in the initial/acute phase of the disease can be challenging. A recent study showed that IgM and IgG seroconversion can occur simultaneously or sequentially in COVID-19, and that antibody titers reach a plateau after 6 days.19 In addition, a meta-analysis of the accuracy of diagnostic tests marketed in Brazil, taken from manufacturers' data, showed a range of 10%-40% false-negative results for detection of SARS-CoV-2 IgM in the acute phase in 8 evaluated tests.41 However, immunological tests have a quick turnaround time and relatively low costs (around £6 per test or USD$ 8-10),42 which may represent an important strength for this method, given the shortages of RT‐PCR and its higher price (around £30/test, but may range from USD$ 25 to 100). Additionally, the participation of multiple manufacturers in the market can potentially scale the immunological tests to millions of people per day due to their simpler design. This may especially help to improve the detection of the virus in health care settings where resources are more limited, such as in developing countries.42 , 43

Our study has some limitations. The included studies differ in terms of size, risk of bias, and external validity. We are aware of potential introduction of bias caused by studies of poor methodological quality. We found high heterogeneity rates among trials, probably cause by some differences in the methods, patient characteristics, and samples used. However, we tried to avoid systematic errors by performing sensitivity analyses, which do not demonstrate significant differences from the original analyses. The eligibility criteria and description of the participants is crucial, as the test is only valid under similar circumstances. Sensitivities, specificities, TP, and TN were compared, but these statistics depend on the populations studied, the reference tests used, and the specific function of the test. Studies were judged as being of moderate methodological quality, with few concerns regarding the applicability of the methods used. The low reporting quality of some studies hampered the performance of further analyses.

CONCLUSIONS

RT-PCR remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of COVID-19 in sputum samples. However, depending on the type of sample and stage of the disease, other methods are preferable. A combination of clinical, molecular, and serological diagnostic tests is highly recommended to achieve adequate sensitivity and specificity. Automated assays for molecular diagnosis using a 2-target system for detecting SARS-CoV-2 should be used whenever possible to enhance analytical performance.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for research funding to the CAPES (Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education within the Ministry of Education of Brazil)—Finance Code 001.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None to report.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.07.011.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.WHO . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn DG, Shin HJ, Kim MH, et al. Current status of epidemiology, diagnosis, therapeutics, and vaccines for novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;30:313–324. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2003.03011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:29. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye Z, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Huang Z, Song B. Chest CT manifestations of new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pictorial review. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:4381–4389. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06801-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO . 2020. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Technical Guidance:Laboratory Testing for 2019-nCoV in Humans.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novelcoronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/laboratory-guidance Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theagarajan LN. Vol. 1. Cornell University; 2020. (Group Testing for COVID-19: How to Stop Worrying and Test More). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalkhen AG, McCluskey A. Clinical tests: sensitivity and specificity. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2008;8:221–223. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang YK, Kang H, Liu X, Tong Z. Combination of RT-qPCR testing and clinical features for diagnosis of COVID-19 facilitates management of SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. J Med Virol. 2020;92:538–539. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo L, Ren L, Yang S, et al. Profiling early humoral response to diagnose novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:778–785. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer B, Drosten C, Muller MA. Serological assays for emerging coronaviruses: challenges and pitfalls. Virus Res. 2014;194:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang YW, Schmitz JE, Persing DH, Stratton CW. The laboratory diagnosis of COVID-19 infection: current issues and challenges. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00512-20. e00512-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, et al. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. Jama. 2018;319:388–396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Vol Version 5.1.02011.

- 17.Whiting PF, Rutjes ASW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;296:E32–E40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long C, Xu H, Shen Q., et al. Diagnosis of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): rRT-PCR or CT? Eur J Radiol. 2020;126 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.108961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan JFW, Yip. CCY, To KKW, et al. Improved molecular diagnosis of COVID-19 by the novel, highly sensitive and specific COVID-19-RdRp/Hel real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay validated in vitro and with clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00310-20. e00310-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cassaniti I, Novazzi F, Giardina F, et al. Performance of VivaDiagTM COVID-19 IgM/IgG Rapid Test is inadequate for diagnosis of COVID-19 in acute patients referring to emergency room department. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M., et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surv. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. 2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li K, Fang Y, Li W., et al. CT image visual quantitative evaluation and clinical classification of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Eur Radiol. 2020;30:4407–4416. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06817-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Yi Y, Luo X, et al. Development and clinical application of a rapid IgM-IgG combined antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;92:1518–1524. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, Liu L, Kou G, et al. Evaluation of Nucleocapsid and Spike Protein-based ELISAs for detecting antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00461-20. e00461-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan Y, Long L, Zhang D, et al. Potential false-negative nucleic acid testing results for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from thermal inactivation of samples with low viral loads. Clin Chem. 2020;66:794–801. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.To KKWT, Tsang OTY, Leung WS, et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet. Infect Dis. 2020;20:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie C, Jiang L, Huang G, et al. Comparison of different samples for 2019 novel coronavirus detection by nucleic acid amplification tests. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu X, Yu C, Qu J, et al. Imaging and clinical features of patients with 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:1275–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04735-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu FY, Yan L, Wang N, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:793–798. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang JC, Wang S, Xue YD. Fecal specimen diagnosis 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020;92:680–682. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao JY, Jr, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2027–2034. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfefferle S, Reucher S, Norz D, Lutgehetmann M. Evaluation of a quantitative RT-PCR assay for the detection of the emerging coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 using a high throughput system. Euro Surv. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000152. 2000152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Udugama B, Kadhiresan P, Kozlowski HN, et al. Diagnosing COVID-19: the disease and tools for detection. ACS Nano. 2020;14:3822–3835. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c02624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu A, Peng Y, Huang B, et al. Genome composition and divergence of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) originating in China. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:325–328. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carter LJ, Garner LV, Smoot JW, et al. Assay Techniques and Test Development for COVID-19 Diagnosis. ACS Cent Sci. 2020;6:591–605. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CDC. 2019. CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) - Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel - Catalog # 2019-nCoVEUA-01 1000 Reactions.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novelcoronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/laboratory-guidance Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 38.CDC . 2019. Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens from Persons for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xing YH, Ni W, Wu Q, et al. Prolonged viral shedding in feces of pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J Microbiol, Immunol Infect. 2020;53:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan L, Liu S. CT and COVID-19: Chinese experience and recommendations concerning detection, staging and follow-up. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:5214–5216. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06898-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castro R, Luz PM, Wakimoto MD, Veloso VG, Grinsztejn B, Perazzo H. COVID-19: a meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy of commercial assays registered in Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2020;24:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020;92:568–576. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.FDA . 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes First Antigen Test to Help in the Rapid Detection of the Virus that Causes COVID-19 in Patients.https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-first-antigen-test-help-rapid-detection-virus-causes Available at: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.