Abstract

The number of cardiovascular imaging studies is growing exponentially, and so is the need to improve clinical workflow efficiency and avoid missed diagnoses. With the availability and use of large datasets, artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to improve patient care at every stage of the imaging chain. Current literature indicates that in the short-term, AI has the capacity to reduce human error and save time in the clinical workflow through automated segmentation of cardiac structures. In the future, AI may expand the informational value of diagnostic images based on images alone or a combination of images and clinical variables, thus facilitating disease detection, prognosis, and decision making. This review describes the role of AI, specifically machine learning, in multimodality imaging, including echocardiography, nuclear imaging, computed tomography, and cardiac magnetic resonance, and highlights current uses of AI as well as potential challenges to its widespread implementation.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, machine learning, cardiac imaging

INTRODUCTION

In its broadest sense, artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the ability of computers to mimic human cognitive function, performing tasks such as learning, problem-solving, and autonomous decision making based on collected data.1 In medicine and cardiology, the goal of AI is to predict a diagnosis or outcome or select the best treatment.2 More and more cardiac imaging investigations are being performed each year, significantly increasing overall health care costs.3 However, imaging studies provide a particularly rich data source that, when combined with clinical information from electronic health records and mobile health devices, can offer abundant opportunities for data-driven discovery and research. Despite the richness of data derived by cardiovascular imaging, traditional statistical approaches often struggle to process and model imaging data in its raw form; this is partly due to the large number and complexity of inputs (or high-dimensional data) that comprise images and videos. Because AI can better handle data with a large number of inputs, it has the potential to advance cardiovascular imaging by facilitating each step of the imaging process, including image acquisition, quantification, analysis, and reporting. Thus, AI improves efficiency while reducing cost.

This review describes the role of AI in cardiovascular imaging, including echocardiography, nuclear imaging, computed tomography (CT), and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR); outlines current uses of AI such as automation, disease recognition, and prediction; and discusses potential challenges for AI in the future.

TERMINOLOGY AND COMPUTATIONAL APPROACHES

Whereas AI describes the concept of using computers to mimic human cognitive tasks,1 machine learning (ML) describes the category of algorithms that enable most current applications described as AI.4 ML algorithms differ in several ways from traditional “rule-based” computer algorithms. First, ML algorithms can “learn” patterns from training data to perform a task of interest without being given specific instructions. Second, many ML algorithms can automatically identify components or groupings from the input data (“features”) that are helpful to perform the task. In imaging, input data for ML can range from a matrix of raw pixel values within an image to summary variables derived from that raw image data, such as measurements or clinically generated reports.5 Generally, the more raw input data and more complex tasks require more complex algorithms and more data. Therefore, building appropriate features to use as inputs into the algorithm may decrease the amount of data and complexity of the model required, presuming the correct a priori assumptions are used to generate the features.

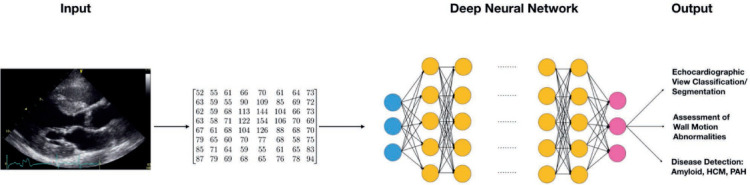

The two general approaches used to train ML algorithms are supervised and unsupervised learning (Table 1).6–17 In supervised learning, the ML algorithm learns based on training data that has been labeled for the task of interest. Prominent examples of supervised ML algorithms include regression (logistic, ridge, elastic net, and LASSO), support vector machines, tree-based methods (random forests and gradient boosted trees), and convolutional neural networks.18,19 Deep learning (DL) refers to the use of neural networks that are composed of more than 3 layers, otherwise called deep neural networks.5 Figure 1 demonstrates how DL can be used for disease detection in cardiovascular imaging, specifically echocardiography.

Table 1.

| TYPE OF MACHINE LEARNING (ML) | DESCRIPTION | COMPUTATIONAL TECHNIQUES | EXAMPLES IN CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING AND DATA SOURCES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised learning | The data is labeled for the outcome of interest. The ML algorithm learns what features from the data drive prediction of the outcome. | Regression analysis, support vector machines, tree-based methods, neural networks (deep learning) | Madani et al. (echocardiographic data, deep learning)6 Zhang et al. (echocardiographic data, deep learning)7 Tabassian et al. (rest and stress echocardiographic data)8 Narula et al. (echocardiographic data)9 Sengupta et al. (speckle tracking echocardiographic data)10 Kusunose et al. (echocardiographic data, deep learning)11 Samad et al. (echocardiographic data)14 Kang et al. (cardiac computed tomography)15 Motwani et al. (cardiac computed tomography)16 Haro Alonso et al. (myocardial perfusion data)17 |

| Unsupervised learning | Key relationships and similarities are identified in a dataset without prior labels or annotations. | Principal component analysis, cluster analysis | Shah et al. (echocardiographic data)12 Lancaster et al. (echocardiographic data)13 |

Figure 1.

Schematic of a deep neural network for imaging data. The input data often is down-sampled to a fixed height and width and nonimaging related data removed to prevent information about the target label from entering the training data. The input image data is represented to the algorithm as a fixed-size matrix corresponding to the image's pixel intensities in standard color channels (ie, red, green, blue). Each matrix (or set of matrices for a color image) represents an image that is fed into the first layer of the neural network (blue nodes). Subsequent layers of the neural network (yellow nodes) can be customized to perform a wide range of functions to the input matrix, transforming the data in a highly flexible way before feeding the data to the next layer of nodes. Deeper layers of nodes tend to learn complex interactions and higher level “features” derived from the input matrix. Each node in each layer of the network adjusts its weights during training, and the entire network is trained using the provided output labels in the training data. Different neural network architectures can be used to achieve object detection, disease classification or segmentation. HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension

After a supervised ML algorithm has been trained, it is important to assess how the algorithm performs on unseen data. Typically, a dataset is separated into “training” (ie, for algorithm development) and “testing” subsets (ie, for algorithm testing). It often is helpful to retain a separate subset of the training dataset for algorithm optimization or tuning. Data used for algorithm training should not be used for testing.4 The generalizability of an algorithm to unseen data depends on several factors, including how well the sampled dataset represents the target data from the intended application and how well the algorithm is optimized to limit overfitting, which occurs when the algorithm learns the noise in the training data, decreasing its performance on new unseen data.4

In unsupervised learning (Table 1), pattern recognition occurs freely within unlabeled data. While less commonly used in medical applications, unsupervised learning has broad potential, particularly in medicine, where the process of annotating data for supervised learning is time-consuming and expensive. Examples of unsupervised learning ML algorithms include clustering algorithms (“k-means” or hierarchical clustering) and principal component analysis.20

IMPLEMENTATION OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is the most widely used imaging modality in cardiology. Ultrasound has many advantages, including availability in most hospital and outpatient settings, portability, and affordability. However, accurate interpretation of echocardiographic data depends on intensive operator training.21 Madani et al. have shown that a DL algorithm performs view classification with the same accuracy as a board-certified echocardiographer.6 Moreover, in a study by Zhang et al., convolutional neural network algorithms were able to perform automated segmentation of cardiac chambers across five common views (Figure 2)7 and, consequently, quantify chamber volumes/mass, ascertain ejection fraction, and determine longitudinal strain through speckle tracking. Measurements of cardiac structure were in line with the study report and commercial software-derived values.7

Figure 2.

Successful discrimination of echocardiographic views using convolutional neural networks. (A) Each cluster of test images corresponds to one of 23 different echocardiographic views, including apical views with or without occlusion of the left atrium. Echocardiographic still images provide examples of a 4-chamber view with and without occlusion of the left atrium. (B) Successful and unsuccessful view classifications within a matrix representation of the test data set. Successful classifications are shown as numbers along the diagonal, whereas misclassifications are indicated as off-diagonal entries. A2c: apical 2-chamber; A3c: apical 3-chamber; A4c: apical 4-chamber; echo: echocardiogram; LV: left ventricular; PLAX: parasternal long axis. Image reproduced from Zhang et al. (Open Access).7

In addition to automated analysis, AI has shown promising results for the classification or diagnosis of several cardiac pathologies. A support vector machine was the most accurate in determining the severity of mitral regurgitation (accuracy > 99% for every degree of severity).22 AI is 87% accurate in identifying myocardial infarction using strain rate curves and segmental deformation.8 Athlete's heart and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can be distinguished using AI with three different classifiers.9 Similarly, an associative memory classifier trained with features from speckle tracking echocardiography generated an area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.96 (by adding four echocardiographic features) to distinguish patients with known restrictive cardiomyopathy and constrictive pericarditis.10 In a DL algorithm, Zhang et al. trained convolutional neural networks to detect hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, cardiac amyloidosis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension with C statistics of 0.93, 0.87, and 0.85, respectively (Figure 1).7 A study by Kusunose et al. using a DL algorithm to detect wall motion abnormalities found that the AUC produced by the algorithm was similar to that produced by the cardiologists and sonographer readers (0.99 vs 0.98, respectively; P = .15) and significantly higher than the AUC of the resident readers (0.99 vs 0.90, respectively; P = .002).11

Characterizing the phenotype of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is yet another diagnostic domain for AI implementation. The heterogeneous profile of HFpEF and lack of a true standard definition make it challenging to manage these patients.23 In a study by Tabassian et al. of patients with HFpEF as well as healthy but hypertensive/breathless control subjects, an ML algorithm was 81% accurate in classifying the patients with HFpEF, with classification based on spatial-temporal rest-exercise features.24 In another study that used imaging and clinical variables to classify and predict outcomes in patients with HFpEF, unsupervised phenomapping of HFpEF patients generated three different phenotypes with significantly different end points of cardiovascular hospitalization or death (AUC was 0.70–0.76 during validation).12 A study by Lancaster et al. using clustering to identify HFpEF patients with high-risk phenotypes found that the clustering groups were more effective at predicting all-cause and cardiac mortality compared with conventional classification of diastolic function.13

In a large cohort of > 170,000 patients, Samad and colleagues predicted all-cause mortality by integrating high-dimensional echocardiographic measurements and electronic medical information into an ML algorithm. Compared with common clinical risk scores (AUC 0.69–0.79), these random forest algorithms had superior prediction accuracy (all AUC = 0.82) and outperformed logistic regression algorithms (P < .001).14

Computed Tomography

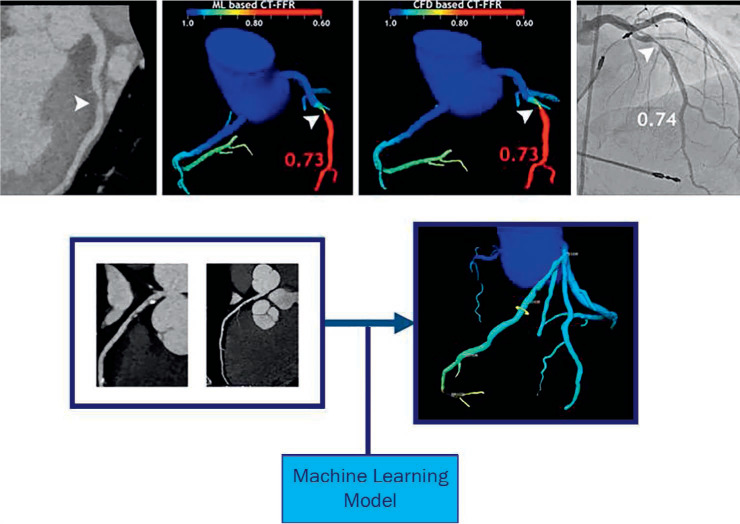

The number of ML-based studies of cardiac CT has multiplied over the last decade. Wolterink et al. developed and validated a DL method to obtain CT images with reduced radiation doses,25 while a similar approach was used to calculate the calcium score from regular coronary CT angiography (CTA), also reducing radiation exposure for the patient.26 In the context of image post-processing, Zreik et al. showed that automated segmentation of the left ventricle (LV) with coronary CTA and convolutional neural networks is feasible and reliable.27 With regard to diagnosing coronary artery disease (CAD), various CTA-derived features have been used for modeling, including physiological features, quantitative plaque measurements, calculations from different spatially connected clusters of heart segmentation, and geometric features of the coronary anatomy (Figure 3).28–33 In a study by Kang et al., an ML algorithm that detected coronary artery stenosis ≥ 25% in CT studies from 42 patient datasets achieved 93% sensitivity, 95% specificity, and 95% accuracy compared to three expert readers (AUC = 0.94).15

Figure 3.

Coronary stenosis (arrowheads) are displayed in different imaging methods. (a) Coronary computed tomography (CT). (b) Calculation of fractional flow reserve (FFR) with a machine learning (ML) algorithm. (c) FFR calculated with computational fluid dynamics. (d) Measurement of the stenosis during invasive coronary angiography. (e) From coronary CT to an AI-based 3-dimensional algorithm of the coronary tree displaying the FFR at different locations along the coronary arteries. Image reproduced from Siegersma et al. (Open Access).33 AI: artificial intelligence

In addition to automated analysis and CAD diagnosis, AI has been used for prognostic purposes in cardiac CT. Motwani et al. used an ML algorithm to predict all-cause 5-year mortality in > 10,000 patients with suspected CAD and found that the algorithm displayed a higher AUC (0.79) compared to conventional cardiac metrics (P < .001).16 Similarly, another study using AI with CT variables to predict major cardiovascular events in patients with suspected CAD reported that the AUC for the ML algorithm was superior to CT severity scores (0.77 vs 0.68–0.70, P < .001).34

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

In CMR, AI has mainly been used for segmentation of cardiac structures and infarct tissue. Winther et al. used DL for automated segmentation of the right and left ventricular endo- and epicardium to calculate cardiac mass and function parameters from a number of datasets.35 Although small sample sizes resulted in limited findings, the ML algorithm achieved outcomes similar to or higher than those predicted by human experts. Tan et al. used a convolutional neural network to automate LV segmentation in all short-axis slices and phases in publicly available datasets.36 In another study by Baessler et al., ML algorithms helped select the most important cine-image-derived texture features to distinguish between patients with myocardial infarction and control subjects. In multiple logistic regression, the use of two texture features generated a 0.92 AUC.37 Implementing this algorithm in clinical practice could potentially expand the eligible patient population and reduce costs since it would preclude the need for gadolinium-enhanced CMR.

Predictive modeling using AI was performed in two CMR studies. In one study, principal component analysis was able to predict 4-year survival in patients with pulmonary hypertension using 3-dimensional (3D) cardiac motion of the right ventricle as an input. This method showed an AUC of 0.73 for including 3D-CMR features in the algorithm in addition to clinical, functional, and regular CMR features and features derived from right-sided heart catheterization (AUC 0.60 without 3D-CMR features).38 In the second study, a predictive algorithm that evaluated deteriorated LV function in patients with a repaired tetralogy of Fallot showed that ML algorithms can be useful for planning early intervention in high-risk patients (AUC 0.87 for major deterioration).39

Nuclear Imaging

AI-based algorithms have been used to classify normal and abnormal myocardium in CAD with accuracy similar to expert human analysis of myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) images.40 Other studies have used AI-based algorithms to detect locations with abnormal myocardium. For example, Nakajima and colleagues found that a neural network trained with expert interpretations of SPECT images was better able to identify stress (AUC 0.92), rest defects (AUC 0.97), and stress-induced ischemia (AUC 0.97) compared with conventional scoring; the AUCs of the summed stress, summed difference, and summed rest scores were 0.82, 0.75 and 0.91, respectively.41

Integrating clinical data with quantitative imaging features in an ML algorithm has been shown to increase the accuracy of SPECT. Arsanjani et al. improved the detection of obstructive CAD with an integrative algorithm that generated a marginally better result than one with solely clinical features (79% vs 76%). Algorithm performance was similar to that of one experienced reader (78%) and better than another (73%).42 Betancur et al. used DL algorithms trained with raw and quantitative perfusion polar maps to predict obstructive CAD more accurately than the current clinical method (AUC 0.80 vs 0.78).43 Another study merged SPECT data with functional and clinical features and showed that ML was comparable to or better than two experienced readers in predicting the need for revascularization.44 Yet another study of major adverse cardiovascular events found that an ML algorithm combining clinical information with myocardial perfusion SPECT data had an AUC higher than the algorithm with only imaging features (0.81 vs 0.78).45

Additionally, Haro Alonso et al. explored the use of AI in predicting cardiac death. Selecting patients who had undergone myocardial perfusion SPECT and using imaging parameters for modeling, the researchers showed that all ML algorithms outperformed baseline logistic regression, with the support vector machine generating the highest AUC (0.77 vs 0.83).17

CHALLENGES IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE APPLIED TO CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING

Although the initial results of AI applications in cardiovascular imaging are promising, some issues must be resolved to implement AI in overall health care. First, further studies are needed to demonstrate that AI leads to higher quality of care, lower health care costs, and improved patient outcomes. Second, standardized methods must be implemented to assure patient privacy and secure information storage or extraction from the electronic health record. Finally, efforts are ongoing to improve comparability of imaging modes. Automated segmentation or extraction of imaging features is likely to be solved first, thus accelerating the analysis of large datasets and the diagnostic and prognostic capabilities of AI.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

AI applications in cardiovascular imaging are rapidly growing. In the short term, AI has the potential to reduce human error and save time in the clinical workflow through automated segmentation of cardiac structures. In the future, AI may expand the informational value of diagnostic images based on images alone or a combination of images and clinical variables, thus facilitating disease detection, prognosis, and decision making. There is also an opportunity to combine biomarker, genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics with imaging data to ultimately improve the predictive value of ML algorithms and create personalized health care for patients.

KEY POINTS

Whereas artificial intelligence (AI) describes the concept of using computers to mimic human cognitive tasks, machine learning (ML) describes the category of algorithms that enable most current AI applications.

The two general approaches used to train ML algorithms are supervised and unsupervised learning. In supervised learning, the ML algorithm learns based on training data that has been labeled for the task of interest. In unsupervised learning, pattern recognition occurs freely within unlabeled data.

AI applications in echocardiography, nuclear imaging, computed tomography, and cardiac magnetic resonance include automation, disease recognition, and prediction of cardiovascular outcomes.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

The authors have completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Russell SJ, Norvig P. Artificial intelligence: a modern approach. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall/Pearson Education; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darcy AM, Louie AK, Roberts LW. Machine Learning and the Profession of Medicine. JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315(6):551–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries. JAMA. 2018 Mar 13;319(10):1024–39. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dey D, Slomka PJ, Leeson P et al. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiovascular Imaging: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar 26;73(11):1317–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JG, Jun S, Cho YW et al. Deep Learning in Medical Imaging: General Overview. Korean J Radiol. 2017 Jul-Aug;18(4):570–84. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2017.18.4.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madani A, Arnaout R, Mofrad M, Arnaout R. Fast and accurate view classification of echocardiograms using deep learning. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:6. doi: 10.1038/s41746-017-0013-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Gajjala S, Agrawal P et al. Fully Automated Echocardiogram Interpretation in Clinical Practice. Circulation. 2018 Oct 16;138(16):1623–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabassian M, Alessandrini M, Herbots L et al. Machine learning of the spatio-temporal characteristics of echocardiographic deformation curves for infarct classification. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017 Aug;33(8):1159–67. doi: 10.1007/s10554-017-1108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narula S, Shameer K, Salem Omar AM, Dudley JT, Sengupta PP. Machine-Learning Algorithms to Automate Morphological and Functional Assessments in 2D Echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Nov 29;68(21):2287–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sengupta PP, Huang YM, Bansal M et al. Cognitive Machine-Learning Algorithm for Cardiac Imaging: A Pilot Study for Differentiating Constrictive Pericarditis From Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Jun;9(6):e004330. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.004330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kusunose K, Abe T, Haga A et al. A Deep Learning Approach for Assessment of Regional Wall Motion Abnormality From Echocardiographic Images. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Feb;13(2 Pt 1):374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah SJ, Katz DH, Selvaraj S et al. Phenomapping for novel classification of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015 Jan 20;131(3):269–79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lancaster MC, Salem Omar AM, Narula S, Kulkarni H, Narula J, Sengupta PP. Phenotypic Clustering of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function Parameters: Patterns and Prognostic Relevance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Jul;12(7 Pt 1):1149–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samad MD, Ulloa A, Wehner GJ et al. Predicting Survival From Large Echocardiography and Electronic Health Record Datasets: Optimization With Machine Learning. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Apr;12(4):681–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang D, Dey D, Slomka PJ et al. Structured learning algorithm for detection of nonobstructive and obstructive coronary plaque lesions from computed tomography angiography. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2015 Jan;2(1):014003. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.2.1.014003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motwani M, Dey D, Berman DS et al. Machine learning for prediction of all-cause mortality in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: a 5-year multicentre prospective registry analysis. Eur Heart J. 2017 Feb 14;38(7):500–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haro Alonso D, Wernick MN, Yang Y, Germano G, Berman DS, Slomka P. Prediction of cardiac death after adenosine myocardial perfusion SPECT based on machine learning. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019 Oct;26(5):1746–54. doi: 10.1007/s12350-018-1250-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shameer K, Johnson KW, Glicksberg BS, Dudley JT, Sengupta PP. Machine learning in cardiovascular medicine: are we there yet? Heart. 2018 Jul;104(14):1156–64. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson KW, Torres Soto J, Glicksberg BS et al. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jun 12;71(23):2668–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krittanawong C, Tunhasiriwet A, Zhang H, Wang Z, Aydar M, Kitai T. Deep Learning With Unsupervised Feature in Echocardiographic Imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Apr 25;69(16):2100–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feigenbaum H. Evolution of echocardiography. Circulation. 1996 Apr 1;93(7):1321–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.7.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moghaddasi H, Nourian S. Automatic assessment of mitral regurgitation severity based on extensive textural features on 2D echocardiography videos. Comput Biol Med. 2016 Jun 1;73:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016 Jul 14;37(27):2129–200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabassian M, Sunderji I, Erdei T et al. Diagnosis of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Machine Learning of Spatiotemporal Variations in Left Ventricular Deformation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018 Dec;31(12):1272–84.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolterink JM, Leiner T, Viergever MA, Isgum I. Generative Adversarial Networks for Noise Reduction in Low-Dose CT. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2017 Dec;36(12):2536–45. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2017.2708987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolterink JM, Leiner T, de Vos BD, van Hamersvelt RW, Viergever MA, Isgum I. Automatic coronary artery calcium scoring in cardiac CT angiography using paired convolutional neural networks. Med Image Anal. 2016 Dec;34:123–36. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zreik M, Leiner T, de Vos BD, van Hamersvelt RW, Viergever MA, Isgum I. I S Biomed Imaging. 2016. Automatic Segmentation of the Left Ventricle in Cardiac Ct Angiography Using Convolutional Neural Networks; pp. 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itu L, Rapaka S, Passerini T et al. A machine-learning approach for computation of fractional flow reserve from coronary computed tomography. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2016 Jul 1;121(1):42–52. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00752.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dey D, Gaur S, Ovrehus KA et al. Integrated prediction of lesion-specific ischaemia from quantitative coronary CT angiography using machine learning: a multicentre study. Eur Radiol. 2018 Jun;28(6):2655–64. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5223-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zreik M, Lessmann N, van Hamersvelt RW et al. Deep learning analysis of the myocardium in coronary CT angiography for identification of patients with functionally significant coronary artery stenosis. Med Image Anal. 2018 Feb;44:72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coenen A, Kim YH, Kruk M et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of a Machine-Learning Approach to Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography-Based Fractional Flow Reserve: Result From the MACHINE Consortium. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Jun;11(6):e007217. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tesche C, Vliegenthart R, Duguay TM et al. Coronary Computed Tomo-graphic Angiography-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve for Therapeutic Decision Making. Am J Cardiol. 2017 Dec 15;120(12):2121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siegersma KR, Leiner T, Chew DP, Appelman Y, Hofstra L, Verjans JW. Artificial intelligence in cardiovascular imaging: state of the art and implications for the imaging cardiologist. Neth Heart J. 2019 Sep;27(9):403–13. doi: 10.1007/s12471-019-01311-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Rosendael AR, Maliakal G, Kolli KK et al. Maximization of the usage of coronary CTA derived plaque information using a machine learning based algorithm to improve risk stratification; insights from the CONFIRM registry. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2018 May-Jun;12(3):204–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winther HB, Hundt C, Schmidt B et al. ν-net: Deep Learning for Generalized Biventricular Mass and Function Parameters Using Multicenter Cardiac MRI Data. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Jul;11(7):1036–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan LK, Liew YM, Lim E, McLaughlin RA. Convolutional neural network regression for short-axis left ventricle segmentation in cardiac cine MR sequences. Med Image Anal. 2017 Jul;39:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baessler B, Mannil M, Oebel S, Maintz D, Alkadhi H, Manka R. Subacute and Chronic Left Ventricular Myocardial Scar: Accuracy of Texture Analysis on Nonenhanced Cine MR Images. Radiology. 2018 Jan;286(1):103–112. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dawes TJW, de Marvao A, Shi W et al. Machine Learning of Three-dimensional Right Ventricular Motion Enables Outcome Prediction in Pulmonary Hypertension: A Cardiac MR Imaging Study. Radiology. 2017 May;283(2):381–90. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samad MD, Wehner GJ, Arbabshirani MR et al. Predicting deterioration of ventricular function in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot using machine learning. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Jul 1;19(7):730–8. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Driessen RS, Raijmakers PG, Danad I et al. Automated SPECT analysis compared with expert visual scoring for the detection of FFR-defined coronary artery disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018 Jul;45(7):1091–1100. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-3951-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakajima K, Kudo T, Nakata T et al. Diagnostic accuracy of an artificial neural network compared with statistical quantitation of myocardial perfusion images: a Japanese multicenter study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017 Dec;44(13):2280–9. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3834-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arsanjani R, Xu Y, Dey D et al. Improved accuracy of myocardial perfusion SPECT for detection of coronary artery disease by machine learning in a large population. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013 Aug;20(4):553–62. doi: 10.1007/s12350-013-9706-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Betancur J, Commandeur F, Motlagh M et al. Deep Learning for Prediction of Obstructive Disease From Fast Myocardial Perfusion SPECT: A Multicenter Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Nov;11(11):1654–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arsanjani R, Dey D, Khachatryan T et al. Prediction of revascularization after myocardial perfusion SPECT by machine learning in a large population. J Nucl Cardiol. 2015 Oct;22(5):877–84. doi: 10.1007/s12350-014-0027-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Betancur J, Otaki Y, Motwani M et al. Prognostic Value of Combined Clinical and Myocardial Perfusion Imaging Data Using Machine Learning. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Jul;11(7):1000–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]