Abstract

Objectives:

The current study was designed to investigate the relationship between the soil arsenic (As) concentration and the mortality from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in mainland China.

Study design:

Ecological study.

Methods:

Twenty-two provinces and 3 municipal districts in mainland China were included in this study. The As concentrations in soil in 1990 was obtained from the China State Environmental Protection Bureau; the data on annual mortality of AD from 1991 to 2000 were obtained from the National Death Cause Surveillance Database of China. Using these data, we calculated the spearman correlation coefficient between soil As concentration and AD mortality, and the relative risk (RR) between soil As levels and AD mortality by quartile-dividing study groups.

Results:

The spearman correlation coefficient between As concentration and AD mortality was 0.552 (p = 0.004), 0.616 (p = 0.001) and 0.622 (p = 0.001) in the A soil As (eluvial horizon), the C soil As (parent material horizon), and the Total soil As (A soil As + C soil As), respectively. When the A soil As concentration was over 9.05 mg/kg, 10.40 mg/kg and 13.10 mg/kg, the relative risk was 0.835 (95 % CI: 0.832, 0.838), 1.969 (95 %CI: 1.955, 1.982), and 2.939 (95 % CI: 2.920, 2.958), respectively; when the C soil As reached 9.45 mg/kg, 11.10 mg/kg and 13.55 mg/kg, the relative risk was 4.349 (95 % CI: 4.303, 4.396), 6.108 (95 % CI: 6.044, 6.172), and 9.125 (95 %CI: 9.033, 9.219), respectively. No correlation was found between lead, cadmium, and mercury concentration in the soil and AD mortality.

Conclusion:

There was an apparent soil As concentration dependent increase in AD mortality. Results of this study may provide evidence for a possible causal linkage between arsenic exposure and the death risk from AD.

Keywords: Arsenic, Soil, Alzheimer’s disease, Mortality

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease and the first leading cause of dementia in the elderly population, which accounts for 60%–80% of dementia cases worldwide [1]. Clinically, the disease is characterized by the loss of memory and other cognitive functions, and the presence of two separate hallmarks, extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles within neurons [2,3]. The prevalence of AD ranges from affecting 3 % of people 60–74 years old to 50 % of people over 85 years old [4], and doubles every five years after the age of 60. As population ageing, AD imposes a significant burden on the society.

Although the etiology of AD is not fully understood, environmental factors including exposure to metals seem to play an important role in the development of AD. Arsenic (As) is a well-known neurotoxin with adverse effects on neurodevelopment and cognitive function in child [5,6]. However, its role in the development of AD in the elderly is rarely evaluated to date. Literature data have reported that levels of As in the ventricular fluid are higher in postmortem samples of AD patients than those obtained from non-demented elderly subjects [7]. A study (Frontier project) conducted in rural-dwelling adults and elders in Texas, U.S., reports that long-term exposure to low levels of As is correlated with significantly poorer performance in the domains of global cognition, language, executive functioning, and memory, which reflects the earliest manifestations of AD [8]. Correlation analyses conducted in European countries also show that slight variations in environmental concentration of arsenic are associated with increases in the morbidity and mortality from AD and other dementias [9]. In animal studies, As exposure has been shown to cause morphologic and neurochemical alterations in the hippocampus and other memory-related neuronal structures, as well as learning and memory deficits [10–12].

To date, most of human studies about As and AD are focused on the association between As exposure in drinking water and the risk of cognitive deficit [13–15]. The current study aimed to investigate the possible association between As exposure in soil and the mortality from AD. Data from 22 provinces and 3 municipal districts in mainland China were used to estimate the relative risk (RR) of AD mortality with As concentrations in the soil, and the correlation coefficient between them. This study may provide evidence for the involvement of As in the development of AD in mainland China.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data resource

The present study include 22 provinces and 3 municipal districts in mainland China, including Anhui; Fujian; Guangdong; Gansu; Guizhou; Hebei; Henan; Heilongjiang; Hubei; Hunan; Jilin; Jiangxi; Jiangsu; Liaoning; Ningxia; Qinghai; Sichuan; Shaanxi; Shandong; Sinkiang; Tibet; and Zhejiang provinces, as well as Beijing; Shanghai and Tianjin municipal districts.

The record of AD deaths and surveillance population in China from 1991 to 2000 was obtained from the National Death Cause Surveillance Database of China [16], which was provided by the Chinese Public Health Science Data Center [16]. From 1991–2000, the Chinese Death Cause Surveillance Web covered 145 surveillance points and 10,000,000 people by stratified cluster random sampling. The AD annual mortality was calculated by dividing the number of AD deaths by the surveillance population over 40 years of age in each district, age and gender were adjusted by the standard population (the year 2000 China population).

The As concentrations in the soil of different provinces and municipal districts were obtained from “Chinese Soil Element Background”, which is published in 1990 by China Environmental Science Press, and the work was conducted by China State Environment Protection Bureau [17]. In the current study, the soil metal concentration included the soil As concentration in the eluvial horizon (A soil As), the soil As concentration in the parent material horizon (C soil As), and the Total soil As concentration (A soil As + C soil As). The A soil layer (the eluvial horizon) is the surface horizon, the zone in which most biological activity occurs. The C soil layer (the parent horizon) refers to the lower layer of the soil and is the soil parent material that has not been significantly affected by the soil development process [18].

2.2. Statistical analysis

The data was constructed and analyzed by the SPSS 17.0 software. The division of provinces and municipal districts to clusters with the Total As concentration was determined by cluster analysis using K-Mean’s method. The ArcGIS 10.1 was used to create the statistical map. Spearman’s correlation was used to estimate the relationship between the soil As concentration and AD mortality. We divided AD deaths and surveillance population into four groups with local soil arsenic concentration by quartile (Q1-Q4). The relative risk (RR) of AD was calculated by dividing AD mortality of higher metal areas (Q2, Q3, Q4) by AD mortality of baseline areas (Q1). 95 % confidence interval for relative risk (RR) was calculated by Woolf method.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of soil As concentrations in mainland China

Detailed information for As and other metals concentrations in the soil is shown in Table 1. A large variation in the As concentrations among the different regions in mainland China was observed, from 6.30 mg/kg to 20.00 mg/kg, from 7.30 mg/kg to 28.50 mg/kg, and from 13.60 mg/kg to 48.50 mg/kg, in A soil As, C soil As, and the Total soil As concentrations, respectively. The median of each layer of soil was 10.40 mg/kg and 11.10 mg/kg in A soil As and C soil As concentrations, respectively. The detailed information for As concentration among the different regions in China were shown in Table 2. The highest A soil, C soil and total soil As concentrations were found in Guizhou province, which reached 20.0 mg/kg, 28.5 mg/kg and 48.5 mg/kg, respectively (Table 2). The lowest A soil, C soil, and Total soil As concentrations were found in Fujian Province, with the value of 6.3 mg/kg, 7.3 mg/kg and 13.6 mg/kg, respectively.

Table 1.

Metal concentration in the soil in mainland China (mg/kg).

| Metal | Soil horizon | Mean | Median | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic | A soil horizon | 11.36 | 10.40 | 3.44 | 6.30–20.00 |

| C soil horizon | 12.01 | 11.10 | 4.31 | 7.30–28.50 | |

| Total soil horizon | 23.37 | 20.20 | 7.56 | 13.60–48.50 | |

| Lead | A soil horizon | 26.06 | 25.40 | 5.78 | 18.80–41.30 |

| C soil horizon | 25.68 | 24.40 | 6.80 | 18.60–47.50 | |

| Total soil horizon | 51.74 | 49.00 | 12.30 | 38.00–88.80 | |

| Cadmium | A soil horizon | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.06–0.14 |

| C soil horizon | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.04–0.14 | |

| Total soil horizon | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.09–0.27 | |

| Mercury | A soil horizon | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02–0.29 |

| C soil horizon | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.01–0.42 | |

| Total soil horizon | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.03–0.70 |

Note: SD: Standard deviation, A soil horizon is the soil concentration in the eluvial horizon, C soil horizon is the soil concentration in the parent material horizon, Total soil horizon is the soil concentration in the eluvial horizon plus the soil concentration in the parent material horizon.

Table 2.

AD mortality and soil metal concentration of administrative areas in mainland China.

| Administrative area | The deaths of AD | Surveillance population | Crude Mortality (1/100,000) | Standardized mortality (1/100,000) | Arsenic (mg/kg) | Lead (mg/kg) | Cadmium (mg/kg) | Mercury (mg/kg) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | C | Total | A | C | Total | A | C | Total | A | C | Total | |||||

| Guizhou | 1,563 | 1,098,644 | 142.27 | 133.6 | 20.0 | 28.5 | 48.5 | 35.2 | 33.1 | 68.3 | 0.659 | 1.244 | 1.903 | 0.110 | 0.188 | 0.298 |

| Hubei | 1,692 | 1,410,413 | 119.96 | 121.4 | 12.3 | 13.3 | 25.6 | 26.7 | 27.1 | 53.8 | 0.172 | 0.137 | 0.309 | 0.080 | 0.078 | 0.158 |

| Ningxia | 170 | 161,528 | 105.24 | 119.9 | 11.9 | 11.8 | 23.7 | 20.6 | 20.3 | 40.9 | 0.112 | 0.119 | 0.231 | 0.021 | 0.019 | 0.040 |

| Tibet | 165 | 125,634 | 131.33 | 117.0 | 19.7 | 19.3 | 39.0 | 29.1 | 29.7 | 58.8 | 0.081 | 0.075 | 0.156 | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.049 |

| Hunan | 3,020 | 2,903,220 | 104.02 | 105.2 | 15.7 | 14.7 | 30.4 | 29.7 | 29.6 | 59.3 | 0.126 | 0.106 | 0.232 | 0.116 | 0.080 | 0.196 |

| Shaanxi | 736 | 871,567 | 84.45 | 104.0 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 21.4 | 21.2 | 42.6 | 0.094 | 0.086 | 0.180 | 0.030 | 0.023 | 0.053 |

| Jiangxi | 648 | 819,229 | 79.10 | 74.4 | 14.9 | 14.3 | 29.2 | 32.3 | 30.4 | 62.7 | 0.108 | 0.095 | 0.203 | 0.084 | 0.053 | 0.137 |

| Jiangsu | 1,414 | 2,148,502 | 65.81 | 59.9 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 20.0 | 26.2 | 24.9 | 51.1 | 0.126 | 0.118 | 0.244 | 0.289 | 0.415 | 0.704 |

| Anhui | 1,024 | 1,842,061 | 55.59 | 57.9 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 18.5 | 26.6 | 26.9 | 53.5 | 0.097 | 0.065 | 0.162 | 0.034 | 0.020 | 0.054 |

| Hebei | 833 | 1,479,092 | 56.32 | 55.0 | 13.6 | 14.2 | 27.8 | 21.5 | 25.1 | 46.6 | 0.094 | 0.097 | 0.191 | 0.036 | 0.022 | 0.058 |

| Sinkiang | 206 | 358,031 | 57.54 | 53.5 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 23.0 | 19.4 | 18.6 | 38.0 | 0.120 | 0.098 | 0.218 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.031 |

| Sichuan | 876 | 1,523,534 | 57.50 | 50.6 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 20.2 | 30.9 | 21.4 | 52.3 | 0.079 | 0.084 | 0.163 | 0.061 | 0.046 | 0.107 |

| Heilongjiang | 334 | 957,251 | 34.89 | 38.6 | 7.3 | 11.4 | 18.7 | 24.2 | 24.4 | 48.6 | 0.086 | 0.078 | 0.164 | 0.037 | 0.040 | 0.077 |

| Shanghai | 185 | 519,145 | 35.64 | 31.2 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 18.1 | 25.0 | 21.0 | 46.0 | 0.138 | 0.133 | 0.271 | 0.095 | 0.043 | 0.138 |

| Guangdong | 479 | 1,464,315 | 32.71 | 30.8 | 8.9 | 10.0 | 18.9 | 36.0 | 40.1 | 76.1 | 0.056 | 0.037 | 0.093 | 0.078 | 0.053 | 0.131 |

| Qinghai | 45 | 210,516 | 21.38 | 28.5 | 14.0 | 13.8 | 27.8 | 20.9 | 22.4 | 43.3 | 0.137 | 0.135 | 0.272 | 0.020 | 0.019 | 0.039 |

| Fujian | 250 | 953,077 | 26.23 | 24.1 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 13.6 | 41.3 | 47.5 | 88.8 | 0.071 | 0.057 | 0.128 | 0.093 | 0.067 | 0.160 |

| Henan | 403 | 1,677,239 | 24.03 | 23.5 | 11.4 | 11.8 | 23.2 | 19.6 | 18.9 | 38.5 | 0.074 | 0.068 | 0.142 | 0.034 | 0.025 | 0.059 |

| Zhejiang | 233 | 1,260,873 | 18.48 | 17.8 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 19.4 | 23.7 | 24.0 | 47.7 | 0.070 | 0.065 | 0.135 | 0.086 | 0.059 | 0.145 |

| Jilin | 78 | 654,268 | 11.92 | 12.5 | 8.0 | 9.4 | 17.4 | 28.8 | 27.3 | 56.1 | 0.099 | 0.080 | 0.179 | 0.037 | 0.025 | 0.062 |

| Beijing | 39 | 397,144 | 9.82 | 7.7 | 9.7 | 8.7 | 18.4 | 25.4 | 23.6 | 49.0 | 0.074 | 0.067 | 0.141 | 0.069 | 0.031 | 0.100 |

| Tianjin | 11 | 352,732 | 3.12 | 2.7 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 19.6 | 21.0 | 18.7 | 39.7 | 0.090 | 0.084 | 0.174 | 0.084 | 0.025 | 0.109 |

| Liaoning | 20 | 1,042,046 | 1.92 | 1.8 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 17.1 | 21.4 | 20.3 | 41.7 | 0.108 | 0.086 | 0.194 | 0.037 | 0.027 | 0.064 |

| Gansu | 9 | 522,187 | 1.72 | 1.7 | 12.6 | 12.7 | 25.3 | 18.8 | 20.3 | 39.1 | 0.116 | 0.122 | 0.238 | 0.020 | 0.009 | 0.029 |

| Shandong | 35 | 2,109,206 | 1.66 | 1.6 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 18.6 | 25.8 | 25.3 | 51.1 | 0.084 | 0.083 | 0.167 | 0.019 | 0.015 | 0.034 |

Note: The deaths of AD: The deaths of AD over 40 years old. Crude Mortality: death cases from AD divided by surveillance population over 40+years old; Standardized mortality: age and gender adjusted using the 2000 China Census Population, and all rates are presented as number of annual deaths /100,000 person 40+ years old; A soil horizon is the soil concentration in the eluvial horizon, C soil horizon is the soil concentration in the parent material horizon, Total soil horizon is the soil concentration in the eluvial horizon plus the soil concentration in the parent material horizon.

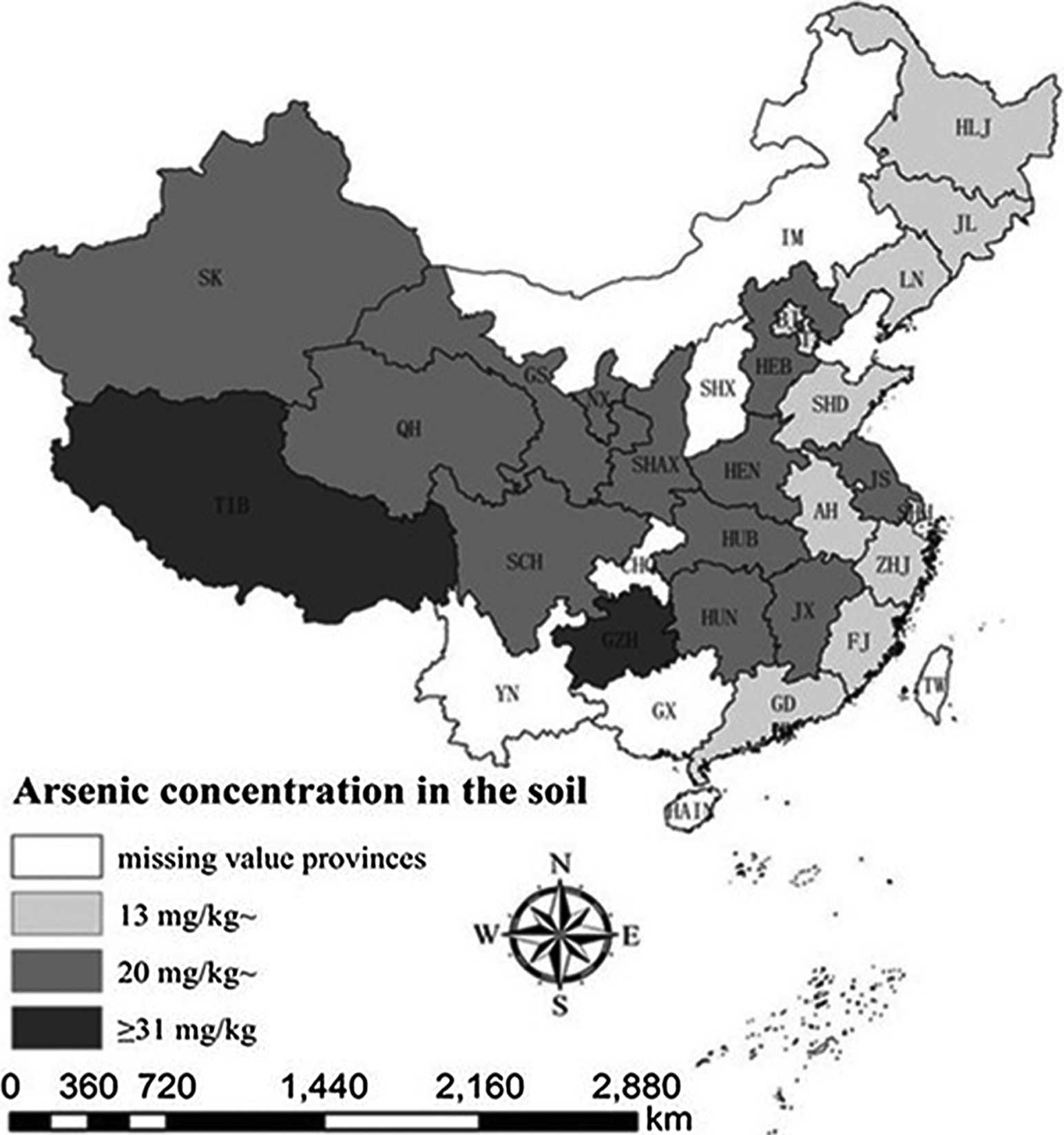

A cluster analysis divided mainland China into three clusters by the Total As concentration in the soil (Fig.1). The Total As concentration in the soil of the first cluster region was between 13–19.9 mg/kg, including 11 districts (light-shaded area). The second cluster was between 20–31 mg/kg, including 12 districts (moderate-shaded area), and the third cluster represented the region with the Total As concentration more than 31 mg/kg, including 2 districts (dark-shaded area) (Fig. 1). Based on this distribution analysis, it was evident that the regions containing higher As concentrations were mainly in the middle and western areas of mainland China. In contrast, most of the low soil As concentration areas, except for Sichuan province, were found in the eastern part of mainland China along the coast.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of arsenic concentration in mainland China determined by cluster analysis using Ward’s method. (AH, Anhui; BJ, Beijing; CHQ, Chongqing; FJ, Fujian; GD, Guangdong; GS, Gansu; GX, Guangxi; GZH, Guizhou; HAIN, Hainan; HEB, Hebei; HEN, Henan; HLJ, Heilongjiang; HK, Hong Kong; HUB, Hubei; HUN, Hunan; IM, Inner Mongolia; JL, Jilin; JX, Jiangxi; JS, Jiangsu; LN, Liaoning; MAC, Macao; NX, Ningxia; QH, Qinghai; SCH, Sichuan; SHAX, Shaanxi; SHD, Shandong; SHH, Shanghai; SHX, Shanxi; SK, Sinkiang; TIB, Tibet; TJ, Tianjin; TW, Taiwan; Yunnan, YN; ZHJ, Zhejiang).

3.2. Positive correlation existed between As concentration in the soil and AD mortality in mainland China

Detailed data on the AD mortality, soil lead, cadmium and mercury concentration were shown in Table 2. We calculated the spearman correlation coefficients between AD annual mortality and metal concentration in the soil. As shown in Table 3, the AD annual mortality was significant correlated with the A soil As concentration (rs = 0.552, p = 0.004), C soil As concentration (rs = 0.616, p = 0.001), and Total soil As concentration (rs = 0.622, p = 0.001).

Table 3.

Correlation between metal and the mortality of Alzheimer’s disease.

| Metal | Soil horizon | Spearman correlation coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic | A soil horizon | 0.552 | 0.004 |

| C soil horizon | 0.616 | 0.001 | |

| Total soil horizon | 0.622 | 0.001 | |

| Lead | A soil horizon | 0.324 | 0.114 |

| C soil horizon | 0.344 | 0.092 | |

| Total soil horizon | 0.342 | 0.094 | |

| Cadmium | A soil horizon | 0.429 | 0.032 |

| C soil horizon | 0.395 | 0.051 | |

| Total soil horizon | 0.388 | 0.055 | |

| Mercury | A soil horizon | 0.200 | 0.337 |

| C soil horizon | 0.333 | 0.104 | |

| Total soil horizon | 0.265 | 0.201 |

Note: A soil horizon is the soil concentration in the eluvial horizon, C soil horizon is the soil concentration in the parent material horizon, Total soil horizon is the soil concentration in the eluvial horizon plus the soil concentration in the parent material horizon.

As reported in several previous articles, lead, cadmium, and mercury are associated with Alzheimer’s disease [19–23]. So we also studied the correlation between the concentration of these metals in the soil and the mortality of Alzheimer’s disease (Table 3). We found that lead and mercury concentration in the soil were not correlated with mortality from AD. The spearman correlation coefficients between AD annual mortality and A soil lead concentration, C soil lead concentration, and Total soil lead concentration is 0.324 (p = 0.114), 0.344(p = 0.092), 0.342(p = 0.094), respectively. The spearman correlation coefficients between AD annual mortality and A soil mercury concentration, C soil mercury concentration, and Total soil mercury concentration is 0.200 (p = 0.337), 0.333(p = 0.104), 0.265(p = 0.201), respectively. A soil cadmium concentration was found to be correlated with AD mortality (rs = 0.429, p = 0.032). We also found positive correlations between the A soil As concentration and the A soil cadmium concentration (rs = 0.450, p = 0.024). To further reveal their relationship, a partial correlation analysis by controlling the effect of A soil cadmium concentrations was conducted, and the results showed that the partial correlation coefficient of AD annual mortality with the A soil As concentration was still significant (rs = 0.563, p = 0.004). When we controlled the effect of A soil As concentration, the correlation between A soil cadmium concentration and mortality from AD disappeared (rs = 0. 146, p = 0.497). These results suggested that significant correlations between the soil As concentrations and the AD mortality seemed unlikely to be mediated by cadmium, but rather a direct effect of As in soil.

3.3. Relative risk between As concentration in the soil and AD annual mortality in mainland China

To investigate the relative risk of soil As in the AD mortality, we further divided the studied regions into four groups with their A soil As concentration (QA1-QA4), C soil As concentration (QC1-QC4) and Total soil As concentration (QT1-QT4) by quartiles. The AD annual mortality of QA1, QC1, QT1 was set as a baseline, from which to estimate the relative risk and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) of the other groups (QA2-QA4, QC2-QC4, QT2-QT4). The baseline data were summarized in Table 4. When the A soil As concentrations were between 6.30–9.05 mg/kg, the AD mortality rate was 31.43/100,000; when the C soil As concentrations were between 7.30–9.45 mg/kg, the AD mortality rate was 10.12/100,000; when the Total soil As concentrations were between 13.60–18.55 mg/kg, the AD mortality rate was 28.09/100,000. Data in Table 4 showed that when the A soil As concentrations exceeded 9.05 mg/kg, 10.40 mg/kg and 13.10 mg/kg, the RR was 0.835 (95 % CI: 0.832– 0.838), 1.969 (95 % CI: 1.955–1.982), and 2.939 (95 % CI: 2.920–2.958), respectively. When the C soil As concentrations exceeded 9.45 mg/kg, 11.10 mg/kg and 13.55 mg/kg, the RR was 4.349 (95 % CI: 4.303–4.396), 6.108 (95 % CI: 6.044–6.172) and 9.125 (95 % CI: 9.033–9.219), respectively. Moreover, when the Total soil As concentrations exceeded 18.55 mg/kg, 20.20 mg/kg and 26.70 mg/kg, the RR was 1.044 (95 % CI: 1.036–1.053), 2.202 (95 % CI: 2.187–2.218) and 3.288 (95 % CI: 3.266–3.310), respectively. Noticeably, the mortality risk of AD was increased, in a dose-dependent fashion, with the increase of As concentrations in soil in mainland China.

Table 4.

The relative risk (95 % CI) of AD mortality according to soil As concentrations.

| soil concentration (mg/kg) | Mortality (1/100,000) | RR (95 %CI) |

|---|---|---|

| A soil As concentration | ||

| QA1 (6.30~) | 31.43 | 1.000 |

| QA2 (9.05~) | 26.25 | 0.835 (0.832, 0.838) |

| QA3 (10.40~) | 61.87 | 1.969 (1.955, 1.982) |

| QA4 (13.10~) | 92.37 | 2.939 (2.920, 2.958) |

| C soil As concentration | ||

| QC1 (7.30~) | 10.12 | 1.000 |

| QC2 (9.45~) | 44.02 | 4.349 (4.303, 4.396) |

| QC3 (11.10~) | 61.82 | 6.108 (6.044, 6.172) |

| QC4 (13.55~) | 92.37 | 9.125 (9.033, 9.219) |

| Total soil As concentration | ||

| QT1 (13.60~) | 28.09 | 1 .000 |

| QT2 (18.55~) | 29.33 | 1.044 (1.036, 1.053) |

| QT3 (20.20~) | 61.87 | 2.202 (2.187, 2.218) |

| QT4 (26.70~) | 92.37 | 3.288 (3.266, 3.310) |

Note: RR: relative risk. QA1-QA4: All districts were divided into four groups with their A soil As concentration; QC1-QC4: All districts were divided into four groups with their C soil As concentration; QT1-QT4: All districts were divided into four groups with their Total soil As concentration.

4. Discussion

In the present study, an ecological study was conducted to quantitatively examine the association between the mortality from AD and the arsenic concentration in soil in mainland China. Results from both correlation analyses and the relative risk studies demonstrate a strong positive association between arsenic concentrations in the soil and the mortality from AD, suggesting an involvement of As in the etiology of AD. In addition, the quartile risk analyses shows a likely soil As concentration-dependent risk of AD in the general Chinese population.

The current study collected both soil As data and the AD mortality rate in China in 1990s. During and prior to that period of time, people in China were not migrating as frequently as they do today. Therefore, the exposure to As in the soil in local inhabitants would most likely lead to a life-long accumulation of As in the body, which may become one of the causes of AD death. While the neurotoxic consequences of As exposure in the etiology of AD or the aging process in general remain to be explored, our data appear to suggest that the chronic As exposure may serve as a factor in the early biological processes leading to AD.

Several studies in literature have shown that arsenic exposure induces changes that coincide with the features of AD. Arsenic toxicity is associated with the reduced neurodevelopmental and cognitive functions in children and adolescents [5,6]. A seminal study led by J. Graziano (2007) reveals that exposure to As from drinking water in 6-year-old children in Bangladesh leads to a reduced intellectual function before and after other interfering factors, such as water Mn, blood lead levels, and sociodemographic characteristics known to contribute to intellectual function are excluded [6]. Whether and how the early As exposure and ensuing neurotoxicities taking place in young children may ultimately lead to the AD etiology in later life are unknown; yet the data from animal studies have provided a clue for the association between As and AD pathology. Arsenic and its metabolites can generate free radicals causing the oxidative stress and neuronal death [24], and they can activate the inflammatory response [25]. These findings are in a good agreement with the oxidative and inflammatory hypotheses of AD [26]. Arsenic exposure is known to induce the hyper phosphorylation of protein tau [27], and increase the production of amyloid-β [28], both of which are involved in the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and brain amyloid plaques [29]. Arsenic is a well-known cardiovascular toxicant that causes cardiovascular diseases [30,31], which is in agreement with the vascular hypothesis of AD. The current vascular hypothesis of AD proposes that the AD is the result of vascular damages which reduces the cerebral blood perfusion rate and therefore indirectly impairs neuron [32,33].

The link between lead, cadmium, mercury with AD has been described in lots of previous studies [19,34]. A case-control study conducted between patients with AD and healthy people showed that AD patients have higher blood lead levels than normal people, and exposure to lead may be a cause of Aβ protein production, with the accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) proteins in the form of plaques that cause molecular and cellular alterations in the brain which is the prominent characteristic of AD [35,36]. In a cross-sectional study, they found that increased blood cadmium was associated with worse cognitive function in adults aged 60 years or older in the USA [37]. An analysis of data from the 1999–2004 Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicated that higher levels of blood cadmium at baseline showed marginally significant association with increased AD mortality in patients over 60 years of age, which total exhibited a 3.83-fold increased risk of AD mortality [21]. In a research experiment, they found that Mercury interacted directly with amyloid beta proteins, which was most important component of senile plaques [38]. Unfortunately, in our study we found that lead, cadmium and mercury in the soil were not associated with mortality from AD.

Soil arsenic was hypothesized to be transferred to the body by foods and water [18,39,40]. Soil-to-plant transfer is an important route of human exposure to metals through food chain, and the metal status of the soil also impacts the metal contents in meat, milk and other animal food because animal feed was grown in the soil [39]. For example, vegetables can uptake and accumulate metals in their entire body including both edible and inedible parts. As to drinking water, soil arsenic was hypothesized to be transferred to body by water since enough evidence suggests ingestion of arsenic in drinking water is the cause of AD [6,11].

The current study has several limitations. First, the current study only adjusted age, gender and metal ions as confounder. Some important confounders, such as smoking, diet, obesity, physical activity and genetic factor, were not controlled. It has been reported that decrease in the incidence of smoking reduced the later prevalence of AD [41]. In overweight and obese subject, cerebral white-matter volume was observed to be associated with more degree of atrophy [42]. In regarding to genetic factor, APOE genotype are well-documented that be associated with increased cerebral Aβ deposition [43]. As an etiology study, the information of above covariates were not provided in the database, and then unable to adjust them. Second, data on As levels in drinking water were not available. Therefore, the comparison with As levels in drinking water is not possible. Considering the natural exchange of metals between soil and water, a high soil As may lead to a high As level in drinking water. Future studies are needed to seek the association between As drinking water exposure and the AD occurrence. Also, As present in the body in multiple species, i.e., arsenite (As3+), arsenate (As5+), monomethylarsonate (MMA), and dimethylarsinate (DMA) [44]. The current study is incapable of differentiating in what species As contributes to its neurotoxicity.

In summary, the results of this study may provide an evidence for a possible causal linkage between arsenic exposure and the death risk from AD. A higher level of As in soil apparently leads to a higher mortality from Alzheimer’s disease, and further large-scale cohort studies are needed to confirm this causal association.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Chinese Public Health Science Data Center and China State Environmental Protection Bureau for data supplied.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81701377), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (ZR2016HM11).

Footnotes

Declarations of Competing Interest

None.

References

- [1].Castellani RJ, Rolston RK, Smith MA, Alzheimer disease, Dis. Mon 56 (2010) 484–546 https://10.1016/j.disamonth.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Glenner GG, Wong CW, Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. 1984, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 425 (2012) 534–539 https://10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Minati L, Edginton T, Bruzzone MG, Giaccone G, Current concepts in Alzheimer’s disease: a multidisciplinary review, Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen 24 (2009) 95–121 https://10.1177/1533317508328602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, Hall K, Hasegawa K, Hendrie H, Huang Y, Jorm A, Mathers C, Menezes PR, Rimmer E, Scazufca M, Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study, Lancet 366 (2005) 2112–2117 https://10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tyler CR, Allan AM, The effects of arsenic exposure on neurological and cognitive dysfunction in human and rodent studies: a review, Curr. Environ. Health Rep 1 (2014) 132–147 https://10.1007/s40572-014-0012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wasserman GA, Liu X, Parvez F, Ahsan H, Factor-Litvak P, Kline J, van Geen A, Slavkovich V, Loiacono NJ, Levy D, Cheng Z, Graziano JH, Water arsenic exposure and intellectual function in 6-year-old children in Araihazar, Bangladesh, Environ. Health Perspect 115 (2007) 285–289 https://10.1289/ehp.9501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Szabo ST, Harry GJ, Hayden KM, Szabo DT, Birnbaum L, Comparison of metal levels between postmortem brain and ventricular fluid in alzheimer’s disease and nondemented elderly controls, Toxicol. Sci 150 (2016) 292–300 https://10.1093/toxsci/kfv325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].O’Bryant SE, Edwards M, Menon CV, Gong G, Barber R, Long-term low-level arsenic exposure is associated with poorer neuropsychological functioning: a Project FRONTIER study, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8 (2011) 861–874 https://10.3390/ijerph8030861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dani SU, Arsenic for the fool: an exponential connection, Sci. Total Environ 408 (2010) 1842–1846 https://10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jacobs JP, December 2014 HeartWeek issue of cardiology in the young: highlights of HeartWeek 2014: diseases of the cardiac valves from the foetus to the adult, Cardiol. Young 24 (2014) 959–980 https://10.1017/s1047951114002285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Luo JH, Qiu ZQ, Shu WQ, Zhang YY, Zhang L, Chen JA, Effects of arsenic exposure from drinking water on spatial memory, ultra-structures and NMDAR gene expression of hippocampus in rats, Toxicol. Lett 184 (2009) 121–125 https://10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Martinez-Finley EJ, Ali AM, Allan AM, Learning deficits in C57BL/6J mice following perinatal arsenic exposure: consequence of lower corticosterone receptor levels? Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 94 (2009) 271–277 https://10.1016/j.pbb.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tyler CR, Allan AM, Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and mRNA expression are altered by perinatal arsenic exposure in mice and restored by brief exposure to enrichment, PLoS One 8 (2013) e73720 https://10.1371/journal.pone.0073720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rodriguez VM, Jimenez-Capdeville ME, Giordano M, The effects of arsenic exposure on the nervous system, Toxicol. Lett 145 (2003) 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Edwards M, Johnson L, Mauer C, Barber R, Hall J, O’Bryant S, Regional specific groundwater arsenic levels and neuropsychological functioning: a cross-sectional study, Int. J. Environ. Health Res 24 (2014) 546–557 https://10.1080/09603123.2014.883591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. http://www.phsciencedata.cn/Share/.

- [17].Station CEM, China-State-Enviromental-Protection-Bureau (1990), Chinese soil element background, Beijing, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Johnson DL, Domier JEJ, Johnson DN, Reflections on the nature of soil and its biomantle, Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr 95 (1) (2005) 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Xu L, Zhang W, Liu X, Zhang C, Wang P, Zhao X, Circulatory levels of toxic metals (Aluminum, cadmium, mercury, lead) in patients with alzheimer’s disease: a quantitative meta-analysis and systematic review, J. Alzheimers Dis 62 (2018) 361–372 https://10.3233/JAD-170811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bihaqi SW, Early life exposure to lead (Pb) and changes in DNA methylation: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease, Rev. Environ. Health 34 (2019) 187–195 https://10.1515/reveh-2018-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Min JY, Min KB, Blood cadmium levels and Alzheimer’s disease mortality risk in older US adults, Environ. Health 15 (2016) 69 https://10.1186/s12940-016-0155-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pigatto PD, Costa A, Guzzi G, Are mercury and Alzheimer’s disease linked? Sci. Total Environ 613–614 (2018) 1579–1580 https://10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Huat TJ, Camats-Perna J, Newcombe EA, Valmas N, Kitazawa M, Medeiros R, Metal toxicity links to alzheimer’s disease and neuroinflammation, J. Mol. Biol 431 (2019) 1843–1868 https://10.1016/j.jmb.2019.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Engstrom KS, Vahter M, Johansson G, Lindh CH, Teichert F, Singh R, Kippler M, Nermell B, Raqib R, Stromberg U, Broberg K, Chronic exposure to cadmium and arsenic strongly influences concentrations of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine in urine, Free Radic. Biol. Med 48 (2010) 1211–1217 https://10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fry RC, Navasumrit P, Valiathan C, Svensson JP, Hogan BJ, Luo M, Bhattacharya S, Kandjanapa K, Soontararuks S, Nookabkaew S, Mahidol C, Ruchirawat M, Samson LD, Activation of inflammation/NF-kappaB signaling in infants born to arsenic-exposed mothers, PLoS Genet. 3 (2007) e207 https://10.1371/journal.pgen.0030207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gong G, O’Bryant SE, The arsenic exposure hypothesis for Alzheimer disease, Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord 24 (2010) 311–316 https://10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181d71bc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Vahidnia A, van der Straaten RJ, Romijn F, van Pelt J, van der Voet GB, de Wolff FA, Arsenic metabolites affect expression of the neurofilament and tau genes: an in-vitro study into the mechanism of arsenic neurotoxicity, Toxicol. In Vitro 21 (2007) 1104–1112 https://10.1016/j.tiv.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dewji NN, Do C, Bayney RM, Transcriptional activation of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid precursor protein gene by stress, Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res 33 (1995) 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gu H, Robison G, Hong L, Barrea R, Wei X, Farlow MR, Pushkar YN, Du Y, Zheng W, Increased beta-amyloid deposition in Tg-SWDI transgenic mouse brain following in vivo lead exposure, Toxicol. Lett 213 (2012) 211–219 https://10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Phan NN, Li KL, Lin YC, Arsenic induces cardiac rhythm dysfunction and acylcarnitines metabolism perturbation in rats, Toxicol. Mech. Methods (2018) 1–9 https://10.1080/15376516.2018.1440679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tsinovoi CL, Xun P, McClure LA, Carioni VMO, Brockman JD, Cai J, Guallar E, Cushman M, Unverzagt FW, Howard VJ, He K, Arsenic exposure in relation to ischemic stroke: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study, Stroke 49 (2018) 19–26 https://10.1161/strokeaha.117.018891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Broderick DF, Schweitzer KJ, Wszolek ZK, Vascular risk factors and dementia: how to move forward? Neurology 73 (2009) 1934–1935 https://10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd6a46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Viswanathan A, Rocca WA, Tzourio C, Vascular risk factors and dementia: how to move forward? Neurology 72 (2009) 368–374 https://10.1212/01.wnl.0000341271.90478.8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yang YW, Liou SH, Hsueh YM, Lyu WS, Liu CS, Liu HJ, Chung MC, Hung PH, Chung CJ, Risk of Alzheimer’s disease with metal concentrations in whole blood and urine: a case-control study using propensity score matching, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 356 (2018) 8–14 https://10.1016/j.taap.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fathabadi B, Dehghanifiroozabadi M, Aaseth J, Sharifzadeh G, Nakhaee S, Rajabpour-Sanati A, Amirabadizadeh A, Mehrpour O, Comparison of blood lead levels in patients with alzheimer’s disease and healthy people, Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen 33 (2018) 541–547 https://10.1177/1533317518794032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Godini R, Pocock R, Fallahi H, Caenorhabditis elegans hub genes that respond to amyloid beta are homologs of genes involved in human Alzheimer’s disease, PLoS One 14 (2019) e0219486.https://10.1371/journal.pone.0219486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li H, Wang Z, Fu Z, Yan M, Wu N, Wu H, Yin P, Associations between blood cadmium levels and cognitive function in a cross-sectional study of US adults aged 60 years or older, BMJ Open 8 (2018) e020533.https://10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Meleleo D, Notarachille G, Mangini V, Arnesano F, Concentration-dependent effects of mercury and lead on Abeta42: possible implications for Alzheimer’s disease, Eur. Biophys. J 48 (2019) 173–187 https://10.1007/s00249-018-1344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jolly YN, Islam A, Akbar S, Transfer of metals from soil to vegetables and possible health risk assessment, SpringerPlus. 2 (2013) 385 https://10.1186/2193-1801-2-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zhang K, Su F, Liu X, Song Z, Feng X, Heavy metal concentrations in water and soil along the Hun River, Liaoning, China, Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 99 (2017) 391–398 https://10.1007/s00128-017-2142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Durazzo TC, Mattsson N, Weiner MW, Smoking and increased Alzheimer’s disease risk: a review of potential mechanisms, Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 10 (2014) S122–S145 https://10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ronan L, Alexander-Bloch AF, Wagstyl K, Farooqi S, Brayne C, Tyler LK, Fletcher PC, Obesity associated with increased brain age from midlife, Neurobiol. Aging 47 (2016) 63–70 https://10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Leoni V, The effect of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype on biomarkers of amyloidogenesis, tau pathology and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease, Clin. Chem. Lab. Med 49 (2011) 375–383 https://10.1515/cclm.2011.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Aposhian HV, Enzymatic methylation of arsenic species and other new approaches to arsenic toxicity, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 37 (1997) 397–419 https://10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]