Abstract

The literature suggests that COVID-19 provokes arterial and venous thrombotic events, although the mechanism is still unknown. In this study, we describe patients with confirmed coronavirus infection associated with multisystemic infarction, focusing on splenic infarction. More data are required to elucidate how COVID-19 and thrombotic disease interact and so that preventive and early diagnosis strategies can be developed.

LEARNING POINTS

Thrombotic disease as a complication of COVID-19 must be suspected by clinicians, and recognized and monitored by radiologists.

Thrombosis is often the initial manifestation of SARS-CoV-2, hence the importance of early diagnosis to avoid complications and reduce morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, pneumonia, coronavirus, disseminated intravascular coagulation, splenic infarction

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a challenge for healthcare systems worldwide, with large numbers of patients requiring intensive care [1]. The disease appears to have a strong thrombotic tendency due to thrombo-inflammation, probably driven by distinct but as yet uncertain processes [2]. These mechanisms may predispose patients to arterial and venous thrombosis [2, 3], although the risk estimates for these complications have not yet been properly defined [4].

Autopsy examinations have demonstrated microcirculation damage in patients with COVID-19 [5], and recent studies suggest that haemostatic abnormalities, including disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), occur in these patients [6]. A study conducted in a hospital in China revealed that 71.4% of those who died with COVID-19 and 0.6% of survivors met criteria for DIC during later stages of the disease [6].

The most consistent haemostatic abnormalities include mild thrombocytopenia [7] and increased D-dimer levels [8], which are associated with severe disease. These haemostatic changes indicate some forms of coagulopathy that may predispose to thrombotic events, although the cause is uncertain [3].

Whether the haemostatic changes are a specific effect of SARS-CoV-2 or whether they are a consequence of cytokine storm that precipitates the onset of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), as observed in other viral diseases, is not completely understood [9, 10]. More data are required on how COVID-19 and thrombotic disease interact [3].

To date, cases of splenic infarction associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection are rare in the literature. However, arteriolar thrombosis and splenic infarction were observed in one patient in a study that evaluated splenic pathological changes identified on autopsy in 10 cases of COVID-19 [11].

CASES SERIES

Patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with splenic infarction and/or other multisystemic infarctions were selected from a hospital database in Ceará-Brazil, based on computed tomography (CT), CT angiography (CTA) and ultrasound findings

Case 1

A 67-year-old, previously hypertensive, male patient was admitted with a 1-day history of weakness in the left upper limbf drooping of the mouth. The patient reported having cough, headache and mild dyspnoea for about 10 days. Naso- and oropharyngeal swabs using the RT-PCR method and rapid test were both positive for SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus infection. CT images showed an area of acute ischemic stroke in the brain (Fig. 1); ground-glass opacities, pulmonary consolidations and findings suggestive of pulmonary thromboembolism (Fig. 2); as well as areas suggestive of splenic infarction (Fig. 3).

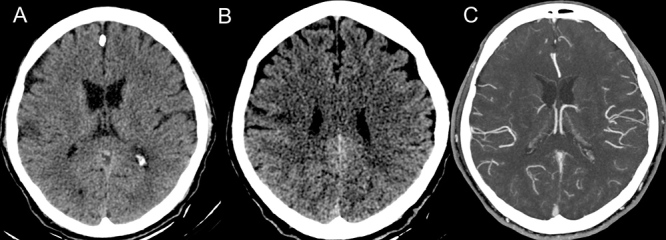

Figure 1.

Non-contrast axial CT showing an area of corticosubcortical hypoattenuation in the right pre-central gyrus (A, B). CTA of the cerebral arteries shows an area with a smaller number of vessels asymmetrically in relation to the contralateral in the right pre-central gyrus, territory of the right middle cerebral artery (C)

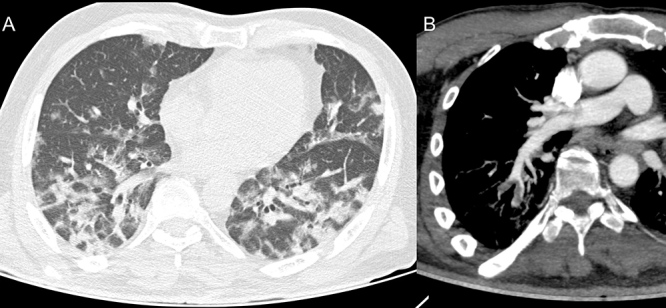

Figure 2.

Axial tomography images of the chest showing ground-glass opacities, some with thickening of interlobular septa, featuring mosaic paving, and some consolidations (A).

CTA of the chest, oblique reconstruction, demonstrating filling defects in arterial branches to the right lower lobe compatible with thromboembolism (B)

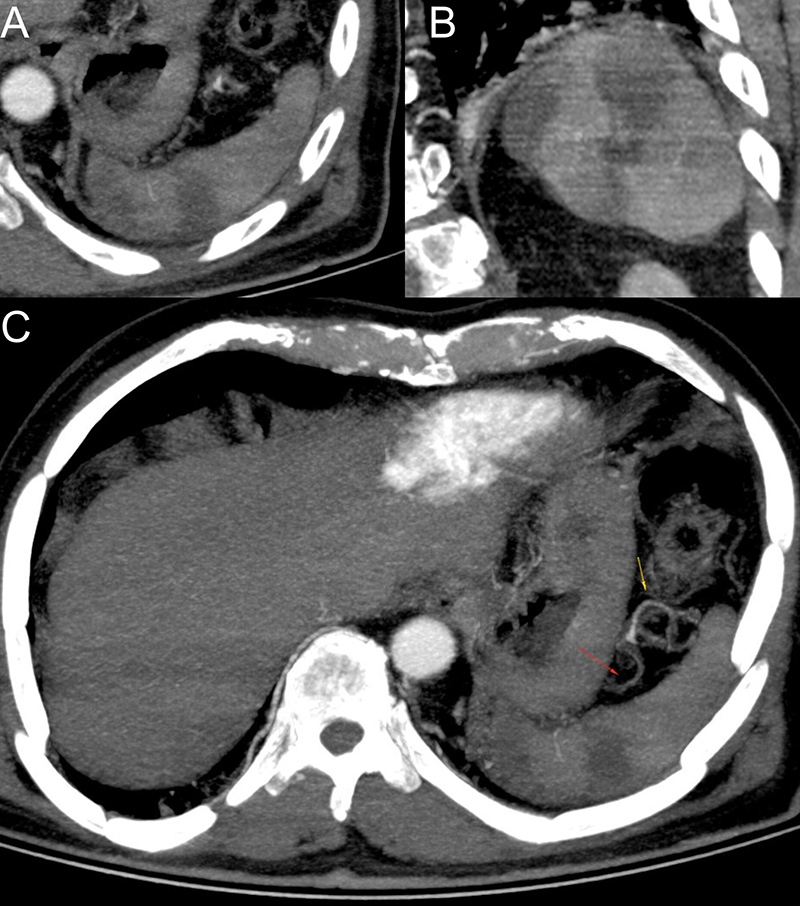

Figure 3.

Axial and coronal CTA images showing wedge-shaped areas based on the convex surface of the spleen and the apex facing the hilar/concave surface compatible with splenic infarctions (A, B). Axial CTA image showing filling defects in segmental branches of the splenic artery featuring thrombi (C)

Case 2

A 53-year-old female patient with rheumatoid arthritis reported dry cough, fever and anosmia, together with dyspnoea. A naso/oropharyngeal swab using the RT-PCR method was positive for SARS-CoV2 coronavirus. The CT images showed areas suggestive of splenic infarction, which was also seen on ultrasound (Fig. 4); CTA confirmed filling failures in the subsegmental branches of the splenic artery (Fig. 5). Chest CT scan showed ground-glass opacities and mosaic paving, suggestive of viral infection (Fig. 6).

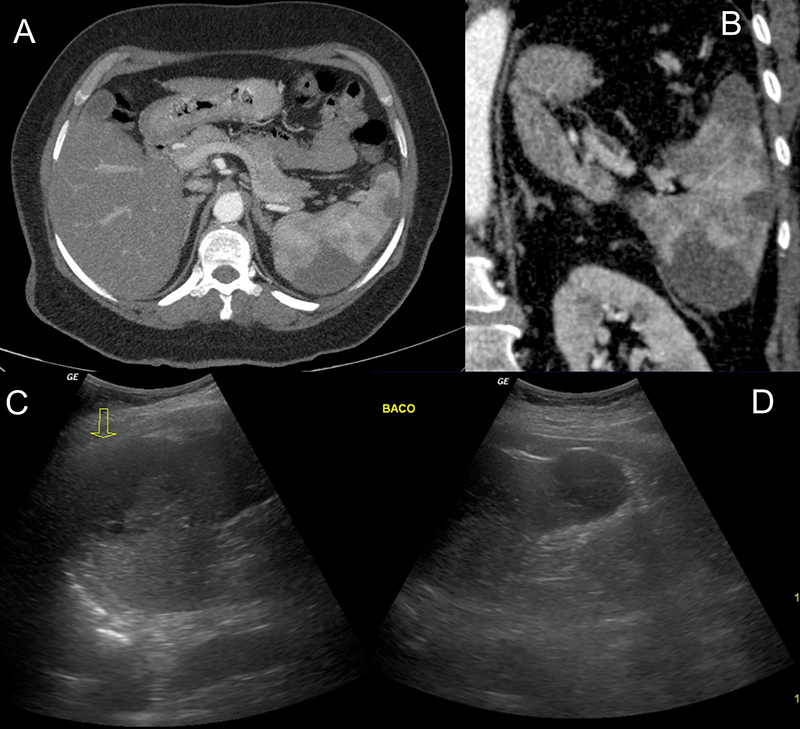

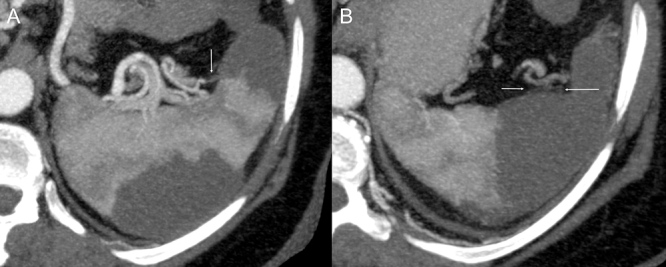

Figure 4.

Axial and coronal abdominal CTA images showing wedge-shaped areas close to the convex face of the spleen compatible with splenic infarctions (A, B). Ultrasound images showing hypoechoic areas suggestive of splenic infarction (C, D)

Figure 5.

CTA images with MIP reformatting showing filling defects in subsegmental branches of the splenic artery near the concave surface, which associated with wedge-shaped areas of no enhancement near the convex face characterize splenic infarctions (A, B)

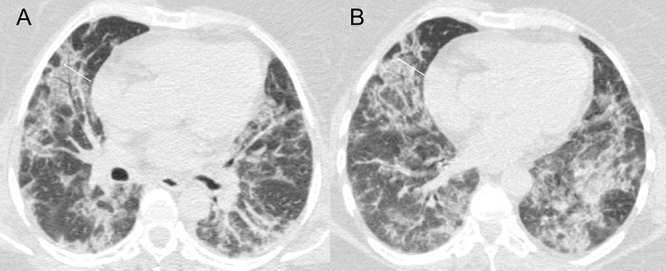

Figure 6.

High resolution axial chest tomography images with radiation dose reduction protocol demonstrating multiple opacity with ground-glass attenuation and thickening of interlobular septa forming a mosaic paving pattern, highlighting perilobular opacity (arrows), involving both lungs in peripheral and peribronchovascular regions (A, B).

DISCUSSION

The described cases highlight splenic infarction as a thrombotic complication of COVID-19. It is extremely important to identify complications associated with this disease. Although thrombotic events are one of the main complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection, reports and imaging findings of splenic infarction are scarce in the literature. The incidence of splenic infarctions is probably underestimated as abdominal imaging is not routinely performed, and they are often incidental findings from chest CT scans that extend to the abdomen.

CONCLUSION

In the current pandemic, clinicians should be aware of thrombotic disease as a complication of COVID-19 and radiologists should monitor patients for thrombosis to facilitate early diagnosis. Further studies should be carried out to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms of COVID-19-related coagulopathy, and so that early preventive and therapeutic strategies can be developed to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: The Authors declare that there are no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marietta M, Ageno W, Artoni A, et al. COVID-19 and haemostasis: a position paper from Italian Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (SISET) Blood Transfus. 2020;18(3):167–169. doi: 10.2450/2020.0083-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui S, Chen S, Li X, et al. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Apr 9; doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 15; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020 Apr 10; doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H, Liu L, Zhang D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet. 2020;395(10235):1517–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30920-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lippi G, Favaloro EJ. D-dimer is associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(5):876–878. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oudkerk M, Büller HR, Kuijpers D, et al. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of thromboembolic complications in COVID-19: report of The National Institute of Public Health for the Netherlands. Radiology. 2020 Apr 23; doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201629. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia X, Xiaona C, Huaxiong P, et al. Pathological changes of the spleen in ten patients with new coronavirus infection by minimally invasive autopsies. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49(0):E014. [Google Scholar]