Abstract

Optimal care occurs when patients possess the skills, knowledge, and confidence needed to effectively manage their health. Promoting such patient activation in kidney disease care is increasingly being prioritized, and patient activation has recently emerged as central to kidney disease legislative policy in the United States. Two options of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Kidney Care Choices model—the Kidney Care First option and the Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting option—now include patient activation as a quality metric; both models specifically name the patient activation measure (PAM) as the patient-reported outcome to use when assessing activation in kidney disease. Because nephrology practices participating in these models will receive capitated payments according to changes in patients’ PAM scores, it is time to more critically evaluate this measure as it applies to patients with kidney disease. In this review, we raise important issues related to the PAM’s applicability to kidney health, review and summarize existing literature that applies this measure to patients with kidney disease, and outline key elements to consider when implementing the PAM into practice and policy. Our aim is to spur further dialogue regarding how to assess and address patient activation in kidney disease to facilitate best practices for supporting patients in the successful management of their kidney health.

Keywords: Patient self-assessment, kidney disease, outcomes

Patient activation, which refers to having the knowledge, skills, and confidence needed to effectively manage one’s own health, is considered an important patient-reported outcome to measure as part of quality-of-care metrics in the United States.1 The Chronic Care Model has highlighted the importance of clinicians interacting with informed and activated patients to optimize care delivery and facilitate the best possible health outcomes.2 On April 7, 2016, the National Quality Forum (NQF) Quality Positioning System endorsed the patient activation measure (PAM) to assess activation in patients across a wide spectrum of care settings and chronic illnesses, including ESKD.3,4 The NQF supports using the PAM to predict and track improvements in a broad range of patient-centered health outcomes, including access to care, care coordination, hospital readmissions, functional status, and medication overuse.

Interest in the PAM has been growing in nephrology. As part of an initiative to develop a framework related to patient-reported outcomes, patient-reported outcome measures, and patient-reported outcome performance measures for patients with ESKD, the Kidney Care Quality Alliance also highlighted the PAM.5 Recently, patient activation was included in two options of the Kidney Care Choices payment model of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS): the Kidney Care First and the Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting models.6 These models aim to determine whether certain incentives will improve both the cost and quality of care along the entirety of a patient’s kidney disease care continuum from nondialysis through dialysis, transplantation, and the end of life. Participating nephrologists and nephrology practices will receive capitated payments on the basis of key quality measures, one of which is the PAM.

The inclusion of the PAM as a quality metric in kidney disease care raises important unanswered considerations. A recent assessment of 60 kidney disease quality metrics conducted by the American Society of Nephrology Quality Committee did not comment on the PAM.7 Thus, it remains to be determined whether the PAM accurately captures the construct of patient activation in a kidney disease population, whether the measure predicts outcomes important to patients and other stakeholders, and if use of the PAM can lead to interventions that result in meaningful improvement in health outcomes in this patient group. To encourage dialogue in this timely area, we provide a brief introduction to and description of the PAM, a review of existing studies applying the PAM in kidney disease, and a summary of remaining knowledge gaps and challenges.

Measuring and Interpreting Patient Activation

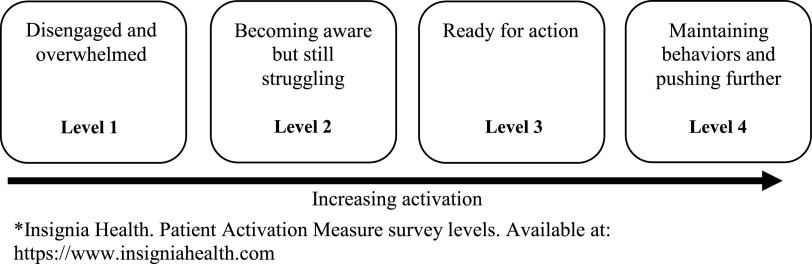

The PAM, currently the most widely used instrument for measuring patient activation, is a commercial scale distributed by Insignia Health that aims to assess an individual’s knowledge, ability, skills, and confidence in self-managing chronic medical conditions.3 The PAM was developed using rigorous methods, which included defining a conceptual framework, generating and testing instrument items, validating the measure in populations with and without chronic disease, and assessing performance of the measure in a national probability sample.8 Scores on the original 22-item scale (22-item patient activation measure [PAM-22]) range from 0 to 100 and are divided into four levels of activation (with lower levels indicating low activation and higher levels indicating high activation): disengagement and disbelief about one’s own role in self-management (level 1, score≤47); increasing awareness, confidence, and knowledge in self-management tasks (level 2, score=47.1–55.1); readiness and taking action (level 3, score=55.2–67); and sustainment (level 4, score>67.1) (Figure 1). The instrument is scored along a Guttman scale, meaning that higher scores along a unidimensional continuum signify a more activated individual.

Figure 1.

Description of four levels of activation on the Patient Activation Measure (PAM).3

The PAM-22 has since been reduced to a 13-item version (13-item patient activation measure [PAM-13]) by its original developers (Supplemental File 1). The shortened scale has also demonstrated internal consistency (Cronbach α-coefficient, 0.87) as well as adequate reliability and validity.9 In the PAM-13, raw scores range from 38.6 to 53.0 and are standardized to a 0–100 scale. Per the original developers, the range of values that correspond to each activation level is similar to those of the PAM-22. The PAM-13 has been translated to multiple languages and adapted to crosscultural differences, and it has demonstrated adequate validity in such chronic conditions as diabetes, HIV disease, and chronic lumbar disease.10–18 The original developers no longer license the 22-item version of the instrument for research or use in health care settings.

According to the NQF, achieving adequate patient activation should be on the basis of a change score calculated from a baseline score and followed by a subsequent measurement taken within 12 months (but not <6 months). Individuals who score at a level of four at baseline would be excluded from the calculation of the change score from a population metric perspective.4 An accountable nephrology unit would be one that reports two PAM scores per patient for at least 50% of their eligible patient population.

Evidence to Support Measuring Patient Activation in Kidney Disease

Patient activation as measured by the PAM-13 is linked to improved health outcomes in chronic conditions other than CKD. Lower PAM-13 scores are associated with an increase in hospitalizations in diabetes (odds ratio [OR], 1.7; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.3 to 2.2). In a study of individuals living with HIV, every five-point increase in the PAM-13 was associated with a greater odds of having a CD4 count >200 cells per milliliter (OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.21) and improved medication adherence (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.29).19,20 Because few studies have administered the PAM-13 to patients with kidney disease, information regarding the determinants and outcomes associated with patient activation in this population is sparse.

We need additional evidence that higher levels of patient activation are associated with clinically meaningful outcomes in kidney disease. Table 1 describes the few published studies that have applied the PAM-13 to patients in this group, with information on study design, the kidney disease subpopulation tested, the prevalence of high and low activation levels in each study, and outcomes associated with these activation levels.21–31 Most studies report cross-sectional associations between patient activation and clinical characteristics. Nearly all studies were completed outside the United States and focus on patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD. In studies that included this information, 20%–30% of individuals reported high activation levels (level 4) at baseline. In general, lower activation levels associated with older age, receiving in-center hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis or transplantation, poorer perceptions of health-related quality of life, higher decisional conflict (uncertainty about which course of action to take) with respect to dialysis modality choice, and lower medication adherence. No studies found associations between patient activation and treatment satisfaction, frequency of hospitalizations, or clinical biomarkers specific to kidney health. Only one study, a randomized, controlled trial of home-based primary care among Zuni Indians with CKD, targeted patient activation as a primary outcome.27

Table 1.

Studies using the PAM-13 in kidney disease

| Investigators, Country of Origin, and Study Design | Population and Sample Size (N) | PAM-13 Activation Level | Characteristics and Outcomes Associated with Patient Activation OR/β (95% CI)a or r (P Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bos-Touwen et al.21 (Netherlands), cross-sectional | CKD (eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; n=219) | Level 1 versus Levels 2–4 | Characteristics: patients with CKD had the lowest activation levels compared with those with DM2, COPD, CHF | |

| Outcomes: multivariable linear regression (R2=0.2 if NS variables of social support and comorbidity score were included in model): BMI, 1.05 (1.01 to 1.08); living alone, 1.50 (1.10 to 2.06); some financial distress, 1.60 (1.17 to 2.18); some education, 1.41 (1.03 to 1.92); disease vintage >5 yr, 0.66 (0.45 to 0.96); depression, 1.05 (1.01 to 1.10); illness perception/understanding, 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04) | ||||

| Hamilton et al.22 (United Kingdom), cross-sectional | HD/PD (n=173); KT (n=417) | Levels 1–4; median: level 3 | Outcomes: multivariable linear regression (R2 not reported): dialysis use, −4.52 (−6.94 to −2.10); younger age of RRT, −3.09 (−5.89 to −3.00); medication adherence (P value for trend <0.01) | |

| Level 1: 26% | ||||

| Level 2: 18% | Level 2: 0.5 (−0.0 to 0.9) | |||

| Level 3: 36% | Level 3: 0.7 (0.3 to 1.1) | |||

| Level 4: 20% | Level 4: 0.6 (0.1 to 1.1) | |||

| Johnson et al.23 (United States), cross-sectional | Comorbid HTN, DM2, CKD (eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; n=62); HD (n=19) | Levels 1–4; Level 1: 10% | Characteristics: patients with stage 5 CKD had lower activation levels compared with those at earlier CKD stages | |

| Level 2: 28% | ||||

| Level 3: 28% | ||||

| Level 4: 34% | Outcomes: no significant associations between patient activation and GFR decline | |||

| Lo et al.24 (Australia), cross-sectional | Comorbid DM2 and CKD (eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; n=199) | Levels 1–4; Level 1: 20% | Characteristics: no significant associations between activation scores and glycemic control or BP control | |

| Level 2: 23% | ||||

| Level 3: 29% | ||||

| Level 3: 29% | ||||

| Magnezi et al.25 (Israel), cross-sectional | Kidney disease (unknown type; n=25) | Characteristics: individuals aged 20–29 had lower activation levels compared with older adults | ||

| The Renal Association,26 National Health Service (England), longitudinal cohort | CKD (unknown eGFR; n=320); HD (n=921); PD (n=51); KT (n=617) | Levels 1–4; Level 1: 25% | Characteristics: those aged 25–44 and those who received KT had the highest activation levels. Patients on HD had lowest activation levels. Those who reported better quality of life had higher activation levels. Inverse relationship between neighborhood deprivation and patient activation level. Inverse relationship between symptom burden and patient activation level | |

| Level 2: 18% | ||||

| Level 3: 33% | ||||

| Level 4: 17% | ||||

| Outcomes: no association between patient activation level and calcium, phosphorus, or hemoglobin overall or by treatment modality. No association between clinician support and patient activation. Resurveying (without an intervention) resulted in improvements in patient activation among those who were previously at levels 1 and 2 | ||||

| Nelson et al.27 (United States), randomized controlled trial | CKD (mean eGFR =101–105 ml/min per 1.73 m2; n=125) | Levels 1–4; Level ≥3: 84% (usual care) versus 68% (home care); mean in both groups: level 3 | PAM-13 as primary outcome: 8.7 points higher on activation score at 12 mo with receipt of home-based care (1.90 to 15.5) | |

| Rivera et al.28 (United States), cross-sectional | CKD (unknown eGFR; n=67) | Levels 1 and 2 versus levels 3 and 4 | Outcomes: no significant associations between activation scores and hospitalizations or emergency department visits | |

| Van Bulck et al.29 (Belgium), cross-sectional | HD (n=192) | Levels 1–4; mean: level 2 | Characteristics: univariable linear regression: age, −0.33; self-reported health, 0.33; nonuniversity higher education, 0.22; university education, 0.21; part-time work, 0.19; full-time work, 0.15; leisure activities, 0.33; having children, −0.22; living alone, 0.33; living with someone, 0.49; >1 care service at home, −0.29; receipt of KT, 0.16; treatment in hospital #2, −0.17. Multivariable linear regression (R2=0.31): age, −0.28; self-reported health, 0.28; leisure activities, 0.21; treatment in hospital #3, −0.02; living with someone, 0.14 | |

| Vélez-Bermúdez et al.30 (United States), cross-sectional | CKD (eGFR=7–25 ml/min per 1.73 m2; n=64) | Levels 1–4; Mean: level 3 | Characteristics: patients who stated they would choose PD had highest activation scores. Pearson correlations: presence of heart disease, −0.28 (<0.05); decisional conflict, −0.47 (<0.01); CKD-related treatment satisfaction, −0.36 (<0.01) | |

| Outcomes: patient activation found to mediate relationship between treatment satisfaction and decisional conflict | ||||

| Zimbudzi et al.31 (Australia), cross-sectional | Comorbid DM2 and CKD (eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; n=305) | Levels 1 and 2 versus levels 3 and 4; levels 1-4 for multivariable linear regression; Level 1: 22% | Characteristics: univariable linear regression: self-care score, 0.21 (0.06 to 0.37); symptoms of kidney disease of KDQOL-36, 0.15 (0.05 to 0.25); burden of kidney disease of KDQOL-36, 0.11 (0.05 to 0.16); effects of kidney disease of KDQOL-36, 0.09 (0.02 to 0.17); PCS, 0.17 (0.01 to 0.33); MCS, 0.26 (0.09 to 0.42). Multivariable linear regression (R2 not reported): self-care score, 0.18 (0.02 to 0.35); burden of kidney disease of KDQOL-36, 0.11 (0.05 to 0.17) | |

| Level 2: 23.6% | ||||

| Level 3: 36.4% | ||||

| Level 4: 18% |

DM2, type 2 diabetes; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF, chronic heart failure; NS, nonsignificant; BMI, body mass index; HD, in-center hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; KT, kidney transplantation; HTN, hypertension; KDQOL-36, Kidney Disease–Related Quality of Life-36; PCS, physical composite summary; MCS, mental composite summary.

If available. All numerical results are statistically significant.

We lack additional evidence that patient activation can be meaningfully improved in kidney disease, but ongoing studies may help answer this question. One upcoming randomized, controlled trial that includes patients with CKD will assess the effect of peer coaching to improve activation as a primary outcome.32 Two other studies, one using a clinical decision support tool to improve the quality of primary care for patients with CKD and another evaluating the effects of a home-based exercise program on cardiac biomarkers in kidney transplant, measure patient activation as a secondary outcome.33,34 The results of these studies will expand our knowledge of the types of interventions likely to be most effective in improving patient activation in the kidney disease population.

Remaining Knowledge Gaps and Challenges in Measuring Patient Activation

Studies have found kidney disease–specific measures of constructs such as knowledge and self-efficacy that contribute to patient activation to be valid and reliable, but these measures have not been used with or compared directly with the PAM-13 in kidney disease populations.35–37 Compared with measuring patient activation for other chronic illnesses, patient activation in the setting of kidney disease may require knowledge and self-management skills that are disease specific. Whether the more general PAM-13 will relate to important clinical outcomes in kidney disease with the same strength as it does in other conditions is unknown. Additionally, the original developers of the PAM use commercial license fees that are on the basis of the size of the target population of interest and operational requirements of the health care organization. This may pose a barrier to widespread implementation and sustained uptake of the PAM.3

Longitudinal studies of behavioral interventions aimed to improve the PAM-13 at a follow-up period of 6 months to 4 years.38–41 This is critical because the length of follow-up selected for a study may have implications for how the success of interventions targeted to improve patient activation is interpreted. For example, a single-center, randomized, controlled trial assessing a home-based integrated disease management intervention’s effect on health-related quality of life, anxiety, depression, and patient activation among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease detected greater improvements in activation at a 24-month follow-up compared with follow-up at 6 or 12 months.40

Studies of behavioral interventions targeting patient activation also do not specify when patient activation must be measured after an intervention, but the Kidney Care First model requires assessing the PAM-13 at 12 months. Neither the length of time required to detect minimally significant or clinically important improvements in patient activation nor the time point of maximal effect have been established in CKD. Furthermore, the threshold of activation associated with the greatest improvement in health outcomes for a patient with kidney disease is also unknown. The NQF has suggested targeting an average increase in six points on the PAM-13 over a period of 6–12 months to achieve an “excellent” improvement in activation.4 In the only published randomized, controlled trial using the PAM-13 as a primary outcome measure in kidney disease, patients in the intervention arm exceeded this metric at 12 months. Mean (SD) activation scores in individuals who received home-based primary care increased from 61.1 (21.2) to 70.3 (21.6), with an average increase in activation score of 8.7 points (95% CI, 1.90 to 15.5).27 Whether patients would have reported higher activation levels at an even longer follow-up duration is unknown.

In its recommendations regarding which patients should subsequently be administered the PAM-13,4 the NQF excludes those with high activation levels at baseline (level 4). Existing studies demonstrate a moderate prevalence of individuals with CKD who score at level 4 on the PAM-13 (17%–34%) (Table 1). In addition, patients with high baseline activation levels may still experience a decline in activation at a later date. One study from the Netherlands of >600 patients with various chronic conditions reported that 31% of patients had an activation level of four at baseline, which declined to 20% at follow-up.42 In another study, individuals who maintained the highest levels of activation over a 2-year follow-up period reported improved health behaviors and better mental health quality of life.43 How to maintain or remediate decline in high patient activation among patients living with kidney disease is unknown. Furthermore, exclusion of patients with high activation scores at baseline from CKD payment models may introduce selection bias. Because systematic differences in sampling methods across facilities could affect payments to facilities, any analysis should consider this issue and include adjustment strategies. Inclusion of all eligible patients in descriptions of patient activation levels over time may be warranted. Rather than excluding individuals with high baseline activation levels, the CMS may consider stratifying individuals by change in score from baseline activation level.

Finally, it is also important to note that the NQF excludes administering the PAM-13 to individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Prevalence estimates for mild cognitive impairment in CKD range from 25% to 62%.44,45 Neither the NQF nor the Kidney Care First model provide details on how cognitive impairment may impair survey response, and individuals with cognitive impairment may truly experience poor confidence and skills in disease-related self-management. Given the increasing age, comorbid disease burden, and accelerated cognitive decline faced by many patients with kidney disease, the rule against administering the PAM-13 to those with mild cognitive impairment may exclude those patients who may most benefit from interventions targeted to improve activation. Experts have outlined strategies to improve the cognitive accessibility of patient-reported outcomes measures that may be applied to PAM-13 administration: leveraging allied health professionals to assist with survey completion, administering the measure during earlier hours of the day, avoiding jargon or complex language prompts, and removing any requirements for extensive written responses.46 Given that the PAM-13 already incorporates some of these suggestions, it may be suitable for patients with mild cognitive impairment.

Lessons from the United Kingdom’s Efforts to Measure Patient Activation in Kidney Disease

We may be able to learn from the United Kingdom’s National Health Service efforts to pilot test implementation of the PAM-13. In partnership with health care organizations and nephrology practices, the National Health Service conducted qualitative and quantitative studies involving interviews with 112 patients and providers (nephrologists and allied health professionals) to assess barriers and facilitators of PAM-13 use as well as test outcomes most strongly associated with the PAM-13.26,47 According to providers, the PAM-13 aligned well with the United Kingdom’s Five Year Forward View, a care model aimed to improve population health, detection of chronic disease, and the overall cost effectiveness of health care.48 Providers also felt that incorporating the PAM-13 into quality-of-care metrics would spur behavioral interventions such as health coaching and catalyze deeper conversations about self-efficacy and motivation. The study participants described difficulties with data management and overall flexibility of collecting PAM-13 data and concerns regarding data privacy and storage. Some providers said they felt the measure was overly complex, expressed concerns that patients who scored poorly would feel stigmatized, and indicated a preference for unstructured conversations with patients as opposed to using a specific measure. Patient views toward the PAM-13 varied, ranging from strong advocacy for the measure’s routine use to confusion regarding the meaning of the concept of patient activation. Patients with multiple chronic diseases were unsure which condition the measure was referring to when they considered their responses.

These qualitative results informed a subsequent quantitative study on the basis of the National Health Service Change Model, an implementation framework that defines shared goals, sets incentives for systems-wide culture change, and incorporates performance measures to guide the sustainment of new processes of care within health systems.49 Between 2015 and 2017, the National Health Service enrolled 14 nephrology practices across England to pilot test the PAM-13.26 According to the results, younger individuals and those who had received a kidney transplant reported higher patient activation levels. Although the study found no demonstrated associations between patient activation and clinical biomarkers linked to kidney health (Table 1), it revealed several findings related to the processes of care needed for the sustained uptake of the PAM-13. First, the United Kingdom Renal Registry infrastructure allowed for the routine collection and return of paper and online survey data to both nephrologists and patients. Second, nurses and allied health care professionals rather than physicians collected the data on patient-reported measures. Challenges included irregular CKD clinic attendance by patients and having a depleted workforce to administer the PAM-13.

On the basis of study results, investigators recommended incorporating patient preferences into the delivery structure of the PAM-13, training allied health professionals in measure collection, training physicians in core behavior change models, and embedding measures into clinical information technology systems (electronic patient-reported outcome measures) to encourage regular use and to allow for patients accessing results. The recommendation about embedding measures into clinical information technology systems is a key point given that the NQF requirement to assess baseline activation levels and measure a change score may require long-term data storage in the electronic medical record.

In addition to incorporating lessons learned from the United Kingdom to leverage allied health professionals, using electronic patient-reported outcome measures to store long-term information and minimize missing data, administering the measure to individuals with mild cognitive impairment, and allowing for a follow-up period of longer than 12 months for scoring, the CMS should consider calculating payments on the basis of models that include patients who report very high activation levels but also, consider adjusting for baseline activation levels and such demographics as socioeconomic status across facilities. Standardized methods for imputing missing values similar to those of the ESRD Quality Incentive Program should be considered.50 Drawing on the lessons learned from the United Kingdom’s implementation efforts and implementing our additional recommendations will maximize the likelihood of successfully incorporating the PAM-13 in line with legislative policy in the United States. All of these strategies would align with kidney community’s mission to be a learning health system.

The PAM-13 has been used as a variable in predictive modeling to both characterize individuals who would most benefit from tailored interventions to improve activation and identify those at greatest risk for increased health care utilization.39,51 Additionally, studies have demonstrated improvements in the PAM-13 in chronic illnesses, including for kidney disease in the setting of home-based primary care, for cancer survivorship in programs that incorporate psychosocial support, and for rheumatoid arthritis self-management with the use of mobile technology.27,52,53 Including patient activation as a quality metric has the exciting potential to pinpoint individuals at greatest risk for poor health outcomes and to catalyze the development of novel patient-centered interventions to improve activation and disease self-management. However, to achieve this, additional rigorous analyses on a larger scale are needed to better understand the specific role and effect of patient activation on patients living with kidney disease.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Cavanaugh is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants P30DK114809 and R01DK103935 and National Institute on Aging grant R56AG061522-01A1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2019121331/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Greene J, Hibbard JH: Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 27: 520–526, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner EH: Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract 1: 2–4, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Insignia Health : Patient activation measure survey. 2004. Available at: https://www.insigniahealth.com/products/pam-survey. Accessed November 17, 2019

- 4.National Quality Forum : Quality positioning system. 2016. Available at: https://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/MeasureDetails.aspx?standardID=2483&print=0&entityTypeID=1. Accessed December 2, 2019

- 5.Kidney Care Quality Alliance : Kidney care quality alliance conference call. 2015. Available at: https://kidneycarepartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/summaryAllKCQACall08-23-16CLEAN.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2019

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services : Kidney care choices model. 2019. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/kidney-care-choices-kcc-model/. Accessed December 2, 2019

- 7.Mendu ML, Tummalapalli SL, Lentine KL, Erickson KR, Lew SQ, Liu F, et al.: Measuring quality in kidney care: An evaluation of existing quality metrics and approach to facilitating improvements in care delivery. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 602–614, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M: Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 39: 1005–1026, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M: Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res 40: 1918–1930, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngooi BX, Packer TL, Kephart G, Warner G, Koh KW, Wong RC, et al.: Validation of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13) among adults with cardiac conditions in Singapore. Qual Life Res 26: 1071–1080, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maindal HT, Sokolowski I, Vedsted P: Translation, adaptation and validation of the American short form Patient Activation Measure (PAM13) in a Danish version. BMC Public Health 9: 209, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graffigna G, Barello S, Bonanomi A, Lozza E, Hibbard J: Measuring patient activation in Italy: Translation, adaptation and validation of the Italian version of the patient activation measure 13 (PAM13-I). BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 15: 109, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNamara RJ, Kearns R, Dennis SM, F Harris M, Gardner K, McDonald J: Knowledge, skill, and confidence in people attending pulmonary rehabilitation: A cross-sectional analysis of the effects and determinants of patient activation. J Patient Exp 6: 117–125, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivera E, Corte C, Steffen A, DeVon HA, Collins EG, McCabe PJ: Illness representation and self-care ability in older adults with chronic disease. Geriatrics 3: 45, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCabe PJ, Stuart-Mullen LG, McLeod CJO, O Byrne T, Schmidt MM, Branda ME, et al.: Patient activation for self-management is associated with health status in patients with atrial fibrillation. Patient Prefer Adherence 12: 1907–1916, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes EL, Long MD, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, Sandler RS: High patient activation is associated with remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 25: 1248–1254, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brenk-Franz K, Hibbard JH, Herrmann WJ, Freund T, Szecsenyi J, Djalali S, et al.: Validation of the German version of the patient activation measure 13 (PAM13-D) in an international multicentre study of primary care patients. PLoS One 8: e74786, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper V, Clatworthy J, Harding R, Whetham J; EmERGE Consortium : Measuring empowerment among people living with HIV: A systematic review of available measures and their properties. AIDS Care 31: 798–802, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Begum N, Donald M, Ozolins IZ, Dower J: Hospital admissions, emergency department utilisation and patient activation for self-management among people with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 93: 260–267, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall R, Beach MC, Saha S, Mori T, Loveless MO, Hibbard JH, et al.: Patient activation and improved outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J Gen Intern Med 28: 668–674, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bos-Touwen I, Schuurmans M, Monninkhof EM, Korpershoek Y, Spruit-Bentvelzen L, Ertugrul-van der Graaf I, et al.: Patient and disease characteristics associated with activation for self-management in patients with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure and chronic renal disease: A cross-sectional survey study. PLoS One 10: e0126400, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton AJ, Caskey FJ, Casula A, Inward CD, Ben-Shlomo Y: Associations with wellbeing and medication adherence in young adults receiving kidney replacement therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1669–1679, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson ML, Zimmerman L, Welch JL, Hertzog M, Pozehl B, Plumb T: Patient activation with knowledge, self-management and confidence in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Care 42: 15–22, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo C, Zimbudzi E, Teede HJ, Kerr PG, Ranasinha S, Cass A, et al.: Patient-reported barriers and outcomes associated with poor glycaemic and blood pressure control in co-morbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease. J Diabetes Complications 33: 63–68, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnezi R, Bergman YS, Grosberg D: Online activity and participation in treatment affects the perceived efficacy of social health networks among patients with chronic illness. J Med Internet Res 16: e12, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Renal Association : Transforming participation in chronic kidney disease. 2019. Available at: https://www.thinkkidneys.nhs.uk/ckd/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2019/01/Transforming-Participation-in-Chronic-Kidney-Disease-1.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019

- 27.Nelson RG, Pankratz VS, Ghahate DM, Bobelu J, Faber T, Shah VO: Home-based kidney care, patient activation, and risk factors for CKD progression in Zuni Indians: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1801–1809, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivera E, Corte C, Steffen A, DeVon HA, Collins EG, McCabe PJ: Illness representation and self-care ability in older adults with chronic disease. Geriatrics (Basel) 3: 45, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Bulck L, Claes K, Dierickx K, Hellemans A, Jamar S, Smets S, et al.: Patient and treatment characteristics associated with patient activation in patients undergoing hemodialysis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 19: 126, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vélez-Bermúdez M, Christensen AJ, Kinner EM, Roche AI, Fraer M: Exploring the relationship between patient activation, treatment satisfaction, and decisional conflict in patients approaching end-stage renal disease. Ann Behav Med 53: 816–826, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimbudzi E, Lo C, Ranasinha S, Fulcher GR, Jan S, Kerr PG, et al.: Factors associated with patient activation in an Australian population with comorbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 7: e017695, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Institutes of Health United States Library of Medicine : ClinicalTrials.gov. 2015. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02429115?term=%22patient+activation+measure%22+kidney&draw=1&rank=2. Accessed February 25, 2020

- 33.National Institutes of Health United States National Library of Medicine : ClinicalTrials.gov. 2019. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03826758?term=%22patient+activation+measure%22+kidney&draw=1&rank=4. Accessed February 25, 2020

- 34.National Institutes of Health United States National Library of Medicine : ClinicalTrials.gov. 2019. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04123951?term=%22patient+activation+measure%22+kidney&draw=1&rank=6. Accessed February 25, 2020

- 35.Wright JA, Wallston KA, Elasy TA, Ikizler TA, Cavanaugh KL: Development and results of a kidney disease knowledge survey given to patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 387–395, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazley AS, Jordan J, Simpson KN, Chavin K, Rodrigue J, Baliga P: Development and testing of a disease-specific health literacy measure in kidney transplant patients. Prog Transplant 24: 263–270, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wild MG, Wallston KA, Green JA, Beach LB, Umeukeje E, Wright Nunes JA, et al.: The Perceived Medical Condition Self-Management Scale can be applied to patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 92: 972–978, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aung E, Donald M, Williams GM, Coll JR, Doi SA: Joint influence of Patient-Assessed Chronic Illness Care and patient activation on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. Int J Qual Health Care 27: 117–124, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blakemore A, Hann M, Howells K, Panagioti M, Sidaway M, Reeves D, et al.: Patient activation in older people with long-term conditions and multimorbidity: Correlates and change in a cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMC Health Serv Res 16: 582, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Titova E, Salvesen Ø, Bentsen SB, Sunde S, Steinshamn S, Henriksen AH: Does an integrated care intervention for COPD patients have long-term effects on quality of life and patient activation? A prospective, open, controlled single-center intervention study. PLoS One 12: e0167887, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hibbard JH, Greene J, Shi Y, Mittler J, Scanlon D: Taking the long view: How well do patient activation scores predict outcomes four years later? Med Care Res Rev 72: 324–337, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rijken M, Heijmans M, Jansen D, Rademakers J: Developments in patient activation of people with chronic illness and the impact of changes in self-reported health: Results of a nationwide longitudinal study in The Netherlands. Patient Educ Couns 97: 383–390, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harvey L, Fowles JB, Xi M, Terry P: When activation changes, what else changes? The relationship between change in patient activation measure (PAM) and employees’ health status and health behaviors. Patient Educ Couns 88: 338–343, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bugnicourt JM, Godefroy O, Chillon JM, Choukroun G, Massy ZA: Cognitive disorders and dementia in CKD: The neglected kidney-brain axis. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 353–363, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otobe Y, Hiraki K, Hotta C, Nishizawa H, Izawa KP, Taki Y, et al.: Mild cognitive impairment in older adults with pre-dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease: Prevalence and association with physical function. Nephrology (Carlton) 24: 50–55, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramer JM, Schwartz A: Reducing barriers to patient-reported outcome measures for people with cognitive impairments. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 98: 1705–1715, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.University of Leicester : Independent evaluation of the feasibility of using the Patient Activation Measure in the NHS in England. 2017. Available at: https://leicester.figshare.com/articles/Independent_evaluation_of_the_feasibility_of_using_the_Patient_Activation_Measure_in_the_NHS_in_England_-_Final_report/10201700. Accessed November 18, 2019

- 48.National Health Service : Five year forward view. 2014. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019

- 49.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services ; Center for Clinical Standards and Quality: CMS ESRD Measures Manual for the 2019 Performance Period. 2019. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/ESRCenD-Manual-v40-.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2020

- 50.National Health Service : Change model. 2012. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/sustainableimprovement/change-model/. Accessed November 18, 2019

- 51.Mitchell SE, Gardiner PM, Sadikova E, Martin JM, Jack BW, Hibbard JH, et al.: Patient activation and 30-day post-discharge hospital utilization. J Gen Intern Med 29: 349–355, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kvale EA, Huang CS, Meneses KM, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bae S, Azuero CB, et al.: Patient-centered support in the survivorship care transition: Outcomes from the Patient-Owned Survivorship Care Plan Intervention. Cancer 122: 3232–3242, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mollard E, Michaud K: A mobile app with optical imaging for the self-management of hand rheumatoid arthritis: Pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 6: e12221, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.