Abstract

Introduction

On February 11, 2020 WHO designated the name “COVID-19” for the disease caused by “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2), a novel virus that quickly turned into a global pandemic. Risks associated with acquiring the virus have been found to most significantly vary by age and presence of underlying comorbidity. In this rapid literature review we explore the prevalence of comorbidities and associated adverse outcomes among individuals with COVID-19 and summarize our findings based on information available as of May 15, 2020.

Methods

A comprehensive systematic search was performed on PubMed, Medline, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar to find articles published until May 15, 2020. All relevant articles providing information on PCR tested COVID-19 positive patient population with clinical characteristics and epidemiological information were selected for review and analysis.

Results

A total of 27 articles consisting of 22,753 patient cases from major epicenters worldwide were included in the study. Major comorbidities seen in overall population were CVD (8.9%), HTN (27.4%), Diabetes (17.4%), COPD (7.5%), Cancer (3.5%), CKD (2.6%), and other (15.5%). Major comorbidity specific to countries included in the study were China (HTN 39.5%), South Korea (CVD 25.6%), Italy (HTN 35.9%), USA (HTN 38.9%), Mexico, (Other 42.3%), UK (HTN 27.8%), Iran (Diabetes 35.0%). Within fatal cases, an estimated 84.1% had presence of one or more comorbidity. Subgroup analysis of fatality association with having comorbidity had an estimated OR 0.83, CI [0.60-0.99], p<0.05.

Conclusions

Based on our findings, hypertension followed by diabetes and cardiovascular diseases were the most common comorbidity seen in COVID-19 positive patients across major epicenters world-wide. Although having one or more comorbidity is linked to increased disease severity, no clear association was found between having these risk factors and increased risk of fatality.

Key Words: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), Coronavirus, Pandemic, Comorbidity, Epidemiology, Fatality or mortality

BACKGROUND

In December 2019, a breakout of pneumonia of unknown etiology was reported in Wuhan City, China, which was subsequently traced to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale market.1 Chinese Health Authorities forewarned the World Health Organization (WHO) about the novel coronavirus outbreak on December 31, 2019, and it was pinpointed as the causative pathogen on January 7, 2020. On February 11, 2020, WHO gave the authorized name COVID-19 for this disease caused by SARS-Cov2, a novel virus genetically related to the coronavirus responsible for the 2003 SARS outbreak. Subsequently, on March 11, 2020 COVID-19 was declared a global health pandemic.2

Since then, the global detection and spread of the virus has been rapid. As of June 29, 2020, COVID-19 has affected 213 countries with more than 10,199,798 confirmed cases, and a gruesome global death toll of 502,947.3 , 4 Basic reproductive number (Ro) has been reported to range from 2.2 to 5.7 in recent studies, and similarly, case fatality rates for the disease varies considerably between countries ranging from 0.04% to 16.33%.5 , 6 Originally, the highest number of deaths were reported in China; however, with the rapid global spread of this virus, several other major epicenters have risen alongside the United States, which has the highest COVID-19 death toll (125,928) as of June 29, 2020.4 Further, current estimates by the IHME, predict even more deaths (113,182-226,971) in the United States by August 2020.7

The clinical manifestations of diagnosed individuals with COVID-19 can be predominantly characterized via a cluster of flu-like symptoms (fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, fatigue, diarrhea, and smell/taste disorder); however asymptomatic cases have also been confirmed.8 Major life-threatening complications of the disease frequently include acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute renal injury (AKI), acute coronary injury, and one or more organ failure or dysfunction.8 , 9 These severe complications seem to be worsened in COVID-19 patients who are elderly (>60) and/or with one or more comorbidities.9, 10, 11, 12 Initial data on clinical characteristics from Wuhan, China suggested that 32% of COVID-19 positive patients had underlying diseases consisting of cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension (HTN), diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).13 Soon after, a Nationwide statistic from China on the clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 patients also revealed that among the diagnosed cases most had one or more coexisting conditions.14 Subsequently, preliminary data from the United States, EU/EEA also confirmed that individuals with major comorbidities including CVD, HTN, diabetes, COPD, CKD, and malignancy seem to be at higher risk than those without these conditions for severe COVID-19 complications.15 , 16 Requirement for hospitalization and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions with COVID-19 have been observed in about 20% of cases with polymorbidity, with case fatality rates as high as 14%.17 Overall, composite data suggests that individuals with chronic underlying illness may have severe outcome risks as high as 10-fold as compared to individuals without any comorbidity.18

Therefore, given the tremendous health and economic burden of COVID-19, thorough evaluation of the association and prevalence of comorbidities in COVID-19 patients is needed in combating this global pandemic. The aim of our review is to explore the prevalence of top global comorbidities (CVD, Diabetes, COPD, Cancer, and CKD) among individuals with COVID-19, as well as investigate any significant associations.19 This review identifies vulnerable patient populations who are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 complications while informing clinicians, policy makers, and researchers as new strategies and policies are developed to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search in PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, SCOPUS and Google Scholar to find all relevant articles which were published until May 15, 2020. The search keywords used in various combinations were “COVID-19 AND Comorbidity OR Chronic Disease,” “COVID-19 AND comorbidities, clinical characteristics, epidemiology,” “SARS-Cov-2 AND Comorbidities,” “coronavirus AND Chronic disease,” “COVID-19 and chronic disease prevalence,” “Covid 19 and chronic illness,” “COVID-19 OR SARS-Cov2 AND Comorbidity OR Chronic Disease OR Underlying Disease,” “Comorbidity” OR “Chronic disease” OR “Underlying Disease” AND “ COVID 19” “coronavirus” “SARS-Cov-2.” Similarly, to avoid missing any relevant literature, we performed additional searches from reference lists of the included studies. Our search was only limited to the English language.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Study types: published primary literatures that provided information and data on comorbidities and individuals diagnosed with COVID-19; (2) Studies included patient dataset with COVID-19, and major comorbidities including: CVD, HTN, Diabetes, COPD, and/or CKD, malignancy, other. Exclusion criteria: (1) Articles that did not contain appropriate and sufficient data regarding major comorbidities listed above; (2) Studies with exclusively pediatric, pregnancy cases, and disease specific studies; (3) Studies not written in English; (4) Discussion summaries, abstracts, case reports, systematic reviews, editorials, and letters.

Data extraction and screening

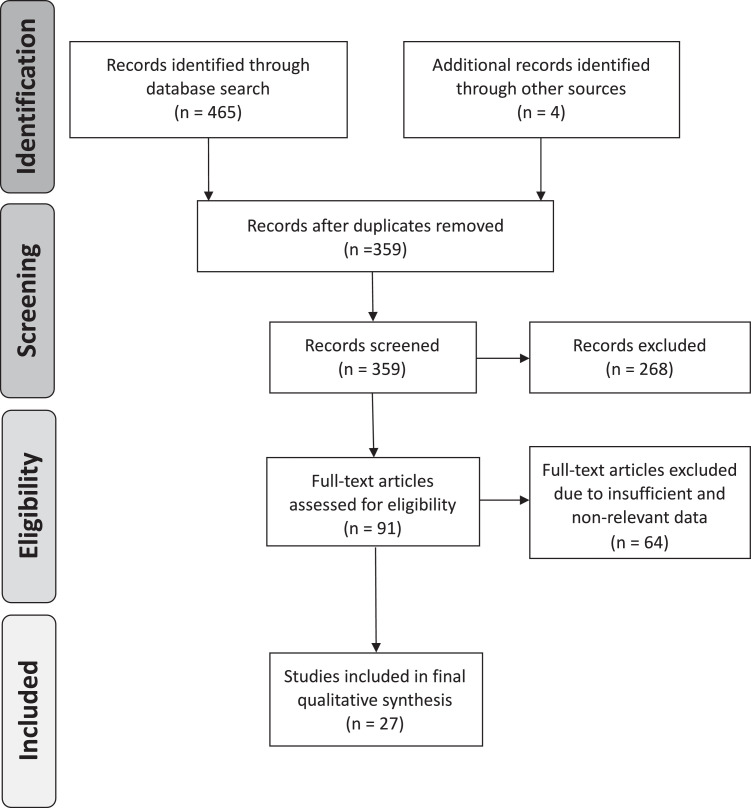

Data extraction and screening were performed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) methodological framework.20 The database searches and other sources (google) identified a total of 469 possibly relevant articles. Following the removal of duplicate articles, 359 were included for further review process. Under the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above, the identified studies were reviewed by all the authors independently. Ninety-one articles qualified for final review after excluding 268 articles from the screening process. Further 64 articles were eliminated after reviewing full-text articles based upon the criteria (Fig 1 ), and a total of 27 peer-reviewed studies were finalized for this study (Table 1 ). Variations between authors were resolved via thorough discussion and concluded with consensus. The agreement for the final studies selection between authors was 91.4% with Cohen's kappa statistic k = 0.72. The following features were obtained for collective assessment: name of the first author, timeline of the study, city/country of the study, sample size, age, sex, and comorbidity data.

Fig 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the literature review and article identification process.

Table 1.

Main characteristics and quality of reviewed studies

| Study (n = 27) | Timeline (mm.dd) | City, country | N = | Age (y)§ | Gender (M/F) | Quality† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cao et al. | Jan 03-Feb 01 | Wuhan, China | 102 | 54 (37-67) | 53/49 | ********** |

| Chen, N et al. | Jan 01-Jan 20 | Wuhan, China | 99 | 55.5 ± 13.1 | 67/32 | ********** |

| Chen, Q et al. | Jan 01-Mar 11 | Zhejiang, China | 145 | 47.5 ± 14.6 | 79/66 | ********** |

| Chen, R et al. | - Jan 31 | China | 50‡ | 69 (51-86) | 30/20 | ********* |

| Chen T et al. | Jan 13-Feb12 | Wuhan, China | 274 | 68 (62-77) | 171/103 | ********** |

| Guan, et al. | - Jan 29 | China | 1,099 | 47 (35-58) | 640/459 | ********** |

| Huang et al. | - Jan 02 | Wuhan, China | 41 | 49 (41-58) | 30/11 | ********* |

| Mo, P et al. | Jan 01- Feb 05 | Wuhan, China | 155 | 54 (42-66) | 86/69 | ********* |

| Wang, D. et al. | Jan 01-Jan 28 | Wuhan, China | 138 | 56 (42-68) | 75/63 | ********** |

| Zhang, G et al. | Jan 02-Feb 10 | Wuhan, China | 221 | 55 (39-66.5) | 108/113 | ********** |

| Zhang, J et al. | Jan 13-Feb 16 | Wuhan, China | 111 | 38 (32-57) | 46/65 | ********** |

| Zhang, JJ et al. | Jan 16-Feb 03 | Wuhan, China | 140 | 57 (25-87) | 71/69 | ********** |

| Zhou et al. | - Jan 31 | Wuhan, China | 191 | 56 (46-67) | 119/72 | ********** |

| Du et al. | Jan 09-Feb 15 | Wuhan, China | 85‡ | 65.8 ± 14.2 | 62/23 | ********** |

| Liu et al. | - Feb 07 | Hubei, China | 137 | 57 (20-83) | 61/76 | ****** |

| Li et al. | - Apr 03 | Wuhan, China | 25‡ | 73 (55-100) | 10/15 | ********* |

| Wang, Z. et. al | - Mar 16 | Wuhan, China | 69 | 42 (35-62) | 32/37 | ********** |

| Ye, et al. | - Apr 01 | China | 1,099 | 47 (35-58) | 640/459 | ********** |

| Jeong, et al. | - Mar 12 | South Korea | 66‡ | 77 (35-93) | 37/29 | ********** |

| Kang, YJ | - Mar 16 | South Korea | 75‡ | 30-80║ | NA | ********* |

| Grasselli, et al. | Feb 20-Mar 18 | Lombardy, Italy | 1,591 | 63 (56-70) | 1,304/287 | ********** |

| Benelli, et al. | Feb 21-Mar 13 | Crema, Italy | 411 | 66.8±16.4 | 359/180 | ******** |

| Carreno, et al. | - April 18 | Mexico | 7,497 | 46 | 4,348/3,149 | ******* |

| McMichael, et al.* | - March 18 | Washington, United States | 167 | 72 (21-100) | 55/112 | ********* |

| Richardson et al. | March 01-Apr 04 | Newark, United States | 5,700 | 63 (52-75) | 3,437/2,263 | ******** |

| Lovell, et al.* | - Apr 20 | United Kingdom | 101 | 82 (72-89) | 64/37 | ******** |

| Nikpouraghdam, et al. | Feb 19-Apr 15 | Iran | 2,964 | 65 (57-75) | 1,959/1,009 | ******** |

Data from long-term care facility.

Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS); NA, Data not available.

Fatal cases.

Mean ± SD or Median (IQR).

Reported as age range in 30s-80s.

Quality assessment

Two authors independently scanned and evaluated the enrolled literatures to ensure reliability. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale,21 with ratings ranging from 1 to 10 stars (*). At least 6 out of 10 stars were considered to represent good to high-quality study. Overall results are presented in Table 1 (full assessment presented in Supplementary Table A).

Analysis

A careful assessment of data and analysis from all included studies was performed to establish and validate any conclusions regarding comorbidity and COVID-19. As such, data extracted from these studies was evaluated to examine the relationship between COVID-19 and comorbidity. Overall COVID-19 patient demographics, prevalence of comorbidities, and any association between major chronic comorbid conditions and COVID-19 outcomes were methodically reviewed. Subsets of pooled studies were used to perform quantitative analysis based on available data in these studies. This included results about correlation between comorbidity and COVID-19 fatality, which were expressed as individual and pooled odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI and P value (alpha < 0.05). All analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (version 16.36).

RESULTS

Characteristics of reviewed studies

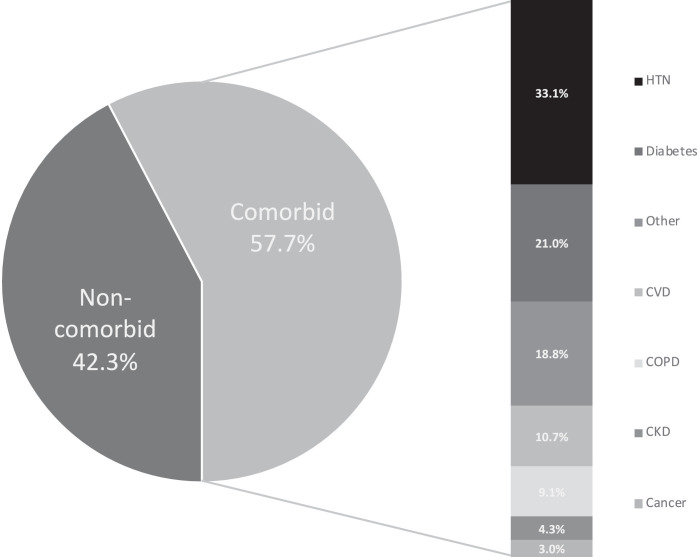

A total of 27 studies (N = 22,753) were included in our review (Table 1).13 , 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 The general timeline of these studies ranged from January 2020 to April 2020 (Table 1). These studies were comprised of data from the following countries: China (18 studies, N = 4,181),22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 South Korea (2 studies, N = 141),39 , 40 Italy (2 studies, N = 2,002),41 , 42 Mexico (1 study, N = 7,497),43 United States (2 studies, N = 5,867),44 , 45 United Kingdom (1 study, N = 101),46 and Iran (1 study, N = 2,964)47 (Table 2 ). The median age of the patient population was approximately 56 [IQR 48.25-67.4] with a male to female ratio of 1.57. Comorbidity data included CVD, HTN, Diabetes, COPD, Cancer, CKD, and other (Fig 2 ). The quality of these studies ranged from good to excellent based on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (Table 1).

Table 2.

Summary of co-morbidity history from COVID-19 patients

| Study | N = | CVD | HTN | Diabetes | COPD | Cancer | CKD | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | ||||||||

| Cao et al. | 102 | 5 | 17 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Chen, N et al. | 99 | 40 | NA† | 12 | 1 | 1 | NA | 3 |

| Chen, Q et al. | 145 | 1 | 21 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 11 |

| Chen, R et al. | 50* | 14 | 28 | 13 | 6 | NA | 5 | 0 |

| Chen T et al. | 274 | 7 | 39 | 23 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Guan, et al. | 1,099 | 42 | 165 | 81 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 25 |

| Huang et al. | 41 | 6 | 6 | 13 | 1 | 1 | NA | 14 |

| Mo, P et al. | 155 | 22 | 37 | 15 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 12 |

| Wang, D. et al. | 138 | 27 | 43 | 14 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 13 |

| Zhang, G et al. | 221 | 37 | 54 | 22 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 10 |

| Zhang, J et al. | 111 | 3 | 15 | 14 | 3 | 8 | NA | 1 |

| Zhang, JJ et al. | 140 | 7 | 42 | 17 | 2 | NA | 2 | 65 |

| Zhou et al. | 191 | 15 | 58 | 36 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 22 |

| Du et al. | 85* | 17 | 32 | 19 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| Liu et al. | 137 | 10 | 13 | 14 | 2 | 2 | NA | 24 |

| Li et al. | 25* | 12 | 16 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Wang, Z. et. al | 69 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 4 | NA | 1 |

| Ye, et al. | 1,099 | 42 | 164 | 81 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 0 |

| Total | 4,181 | 315 | 759 | 410 | 89 | 80 | 57 | 210 |

| South Korea | ||||||||

| Jeong, et al. | 66* | 15 | 30 | 23 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| Kang, YJ | 75* | 47 | NA† | 35 | 18 | 10 | 11 | 25 |

| Total | 141 | 62 | 30 | 58 | 29 | 17 | 16 | 30 |

| Italy | ||||||||

| Grasselli, et al. | 1,591 | 223 | 509 | 180 | 42 | 81 | 36 | 426 |

| Benelli, et al. | 411 | 93 | 193 | 67 | 48 | 33 | 22 | 0 |

| Total | 2,002 | 316 | 702 | 247 | 90 | 114 | 58 | 426 |

| United States | ||||||||

| McMichael, et al. | 167 | 68 | 67 | 38 | 36 | 15 | 43 | 52 |

| Richardson et al. | 5,700 | 966 | 3,026 | 1,808 | 920 | 320 | 454 | 128 |

| Total | 5,867 | 1,034 | 3,093 | 1,846 | 956 | 335 | 497 | 180 |

| Mexico | ||||||||

| Carreno, et al. | 7,497 | 225 | 1,544 | 1,252 | 472 | NA | 142 | 2,668 |

| United Kingdom | ||||||||

| Lovell, et al. | 101 | 34 | 54 | 36 | 22 | 25 | 21 | 2 |

| Iran | ||||||||

| Nikpouraghdam, et al. | 2,964 | 37 | 59 | 113 | 60 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| Total N (%) | 22,753 | 2,023 (8.9%) | 6,241 (27.4%) | 3,962 (17.4%) | 1,718 (7.5%) | 588 (2.6%) | 809 (3.5%) | 3,535 (15.5%) |

Fatal cases.

Data reported within CVD; NA: data not available.

CVD, cardiovascular disorders; HTN, hypertension; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Other: liver disease, GI disorders, immunocompromised, neurological disorders, psychiatric disorders, metabolic disorders, blood disorders, transplant, chronic pancreatitis, connective tissue disorder, smoking, obesity, hyperlipidemia.

Fig 2.

Overall proportions of comorbid and noncomorbid COVID-19 patient populations in reviewed studies; including distribution of major disease categories. Comorbidity legend matches individual categories (highest to lowest %) as listed.

Comorbidity specific characteristics

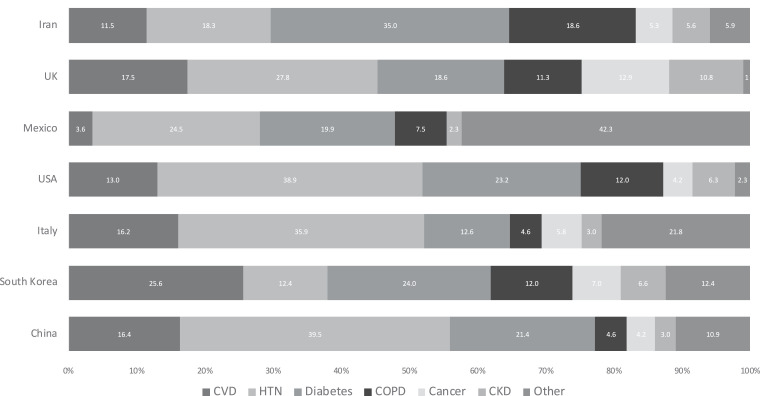

Among the 22,753 COVID-19 positive patient population, 42.3% patients were without any chronic comorbid condition, while 57.7% had one or more comorbidity (Fig 2). Major comorbidities in overall population (N = 22,753) were CVD (8.9%), HTN (27.4%), Diabetes (17.4%), COPD (7.5%), Cancer (3.5%), CKD (2.6%), and other (15.5%) (Table 2). Further, comorbidity distribution within the comorbid population group (N = 13,050) were CVD (10.7%), HTN (33.1%), Diabetes (21%), COPD (9.1%), Cancer (3%), CKD (4.3%), and other (18.8%) (Fig 2). Hypertension followed by diabetes and CVD/COPD were the most common comorbidities seen in these COVID-19 positive patient populations (Table 1). Further examination of country specific major comorbidities (Fig 3 ) also had HTN as one of the most common comorbidities across all groups. However, major comorbidity specific to each country varied as follows – China (HTN 39.5%), South Korea (CVD 25.6%), Italy (HTN 35.9%), United States (HTN 38.9%), Mexico, (Other 42.3%), United Kingdom (HTN 27.8%), Iran (Diabetes 35%) (Fig 3). Diabetes was the second most common comorbidity in 5 of 7 countries reviewed.

Fig 3.

Distribution of major comorbidities in various COVID-19 epicenters around the world. Data labels within each country match the comorbidities in order as listed. Cancer data not available for Mexico.

Comorbidity and COVID-19 fatality

A subset of studies from the final screening, which included data specific to fatality was used to pool and assess association between comorbidity and COVID-19 mortality. These included studies reporting fatal/nonfatal cases (4 studies, N = 3,751)22 , 23 , 42 , 47); and studies reporting only fatal cases (5 studies, N = 301).26 , 34 , 36 , 39 , 40 Based on studies reporting data on both fatal and nonfatal outcomes, association between comorbidity and COVID-19 fatality was evaluated; and 3/4 studies showed a strong correlation between having one or more comorbidity and fatality (Cao et al. OR 4.88, CI [1.47-16.21], P < .05; Chen, T et al. OR 2.70, CI [1.64-4.43], P < .05; Benelli et al. OR 4.10, CI [2.08-8.06], P < .05, while one showed no such correlation (Nikpouraghdam et al. OR 0.62, CI [0.43-0.89], P < .05) (Table 3 ). Overall, based on all 4 studies (Pool 1) no significant correlation was found between comorbidity and fatality in COVID-19 patients- OR 0.83, CI [0.60-0.99], P < .05 (Supplementary Table B). However, pooling of the first 3 studies (Pool 2) with significant results did show an overall strong correlation -OR 2.57, CI [1.82-3.63], P < .05. Similarly, no significant correlation between any specific comorbidity evaluated in this review and COVID-19 fatality was seen in Pool1; with only HTN showing positive correlation to fatality (OR 1.65, CI [1.01-1.85], P < .05) in Pool 2 (Supplementary Table B).

Table 3.

Summary of fatal and nonfatal cases with comorbidity in COVID-19 patients

| Comorbidity | Cao et al. | Chen T, et al. | Benelli, et al. | Nikpour., et al. | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = Fatal (Nonfatal) cases | |||||

| Total (N =) | 13 (34) | 71 (62) | 61 (195) | 201 (2,240) | 346 (2,531) |

| CVD | 6 (5) | 21 (7) | 28 (65) | 4 (33) | 59 (110) |

| HTN | 11 (17) | 54 (39) | 48 (145) | 8 (51) | 121 (252) |

| Diabetes | 6 (5) | 24 (23) | 25 (42) | 11 (102) | 66 (172) |

| COPD | 4 (6) | 11 (7) | 10 (38) | 9 (51) | 34 (102) |

| Cancer | 1 (3) | 5 (2) | 9 (24) | 1 (16) | 16 (45) |

| CKD | 3 (1) | 1 (4) | 11 (11) | 3 (15) | 18 (31) |

| Other | 2 (4) | 8 (12) | 0 | 2 (17) | 12 (33) |

| OR [95% CI], P value |

4.88 [1.47-16.21] <.05 |

2.70 [1.64-4.43] <.05 |

4.10 [2.08-8.06] <.05 |

0.62 [0.43-0.89] <.05 |

0.83 [0.60-0.99] <.05 |

Similarly, upon reviewing a subset of studies reporting only fatal cases, overall fatality was seen in 84.1% of patients with one or more comorbidity. Major comorbidity specific data showed significant fatality in CVD (34.9%), HTN (35.2%), and Diabetes (33.2%) groups, with comparatively lesser fatality in COPD (13%), CKD (8.3%), Cancer (9.6%), and other (11.6%) group (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Summary of fatal cases with comorbidity and COVID-19

| Comorbidity | Chen, R et al.* | Du et al.* | Li et al.* | Jeong, et al.* | Kang, YJ* | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N/n | 50/35 | 85/58 | 25/25 | 66/61 | 75/74 | 301/253 (84.1%) |

| CVD | 14 | 17 | 12 | 15 | 47 | 105 (34.9%) |

| HTN | 28 | 32 | 16 | 30 | NA | 106 (35.2%) |

| Diabetes | 13 | 19 | 10 | 23 | 35 | 100 (33.20%) |

| COPD | 6 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 18 | 39 (13%) |

| Cancer | NA | 6 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 25 (8.3%) |

| CKD | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 29 (9.6%) |

| Other | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 25 | 35 (11.6%) |

Studies reporting only fatal cases.

N: total patient population with fatal outome; n: patients with one or more comorbidiy and fatal outcome.

DISCUSSION

The persistently increasing number of COVID-19 cases and the devastating death toll is an emergent and widespread concern for social, health, and economic sectors around the globe.48 Yet, so far, no effective treatment has been established and the pathogenesis of this novel virus still remains unclear.49 Daily reports of new diagnostic and death peaks are being reported from various active and emerging epicenters around the world, with a plethora of studies examining and reporting on the risks of severe complications and mortality in COVID-19 patients. Higher age group (>60, Median 34-59) is a well-observed risk factor for severe outcome; however, emphasis on caution for younger individuals is also emerging and advocated by major health agencies.9 , 10 , 50 , 51 Early and current scientific reports have also identified the presence of one or more coexisting comorbidities, particularly in severe COVID-19 patient groups.14, 15, 16 These common comorbidities include CVD, HTN, Diabetes, COPD, CKD, and Cancer. According to the WHO statistics on chronic conditions, these aforementioned diseases account for the most common and leading cause of mortality worldwide.19 Therefore, in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic, health experts believe that the presence of any coexisting comorbidity puts an individual with COVID-19 at higher risk for severe clinical outcome, including death.27 A recent report from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine estimates that around 1.7 billion individuals globally have one or more comorbid conditions which might increase their risk of severe COVID-19 complications.52 Based on our review of the most current literature consisting of data from several major COVID-19 epicenters, we see that one or more comorbid conditions is indeed more prevalent (57.7% vs 42.3%) among COVID-19 positive individuals (Fig 2). Further, comorbidity seems to be even more prevalent in patients with fatal outcomes, with 84.1% of these individuals having one or more comorbidity (Table 4). Although the link between increased disease severity and presence of comorbidity is well-established, comorbidity and its effect on mortality remains an unclear question, with increased risk to no risk seen in several recently published studies.10 , 53, 54, 55 In our review, we report similar findings, with overall 2.57 times increased risk of fatality with one or more comorbidity in several pooled studies, and no such correlation in another pool (Table 3/Supplementary Table B). As such, no distinct conclusions regarding comorbidity and fatality can be drawn, and the subject requires further study with larger population groups and multi-center/national investigations. Current knowledge and our findings on specific major comorbidities are discussed in further detail below.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD)

CVDs including hypertension, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, account for an estimated 17.9 million annual deaths worldwide.56 These groups of disorders of the heart and blood vessels are the leading cause of global mortality and morbidity.56 , 57 Viral infectious diseases can cause a variety of CVDs, including myocarditis, pericarditis leading to arrhythmias and heart failure.58 In COVID-19, although the exact mechanism of myocardial injury is still in question, new studies have revealed a possible link with Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression in cardiac tissues.59 Studies show that acute cardiac injury occurs in about 7%-28% of all COVID-19 cases, and among these lead to death in about 10.5% (vs 0.9%) of cases with underlying CVD.60, 61, 62 Among the spectrum of CVDs, hypertension has been observed to be the most prevalent (∼30%), and similarly leading cause of death in about 6% of cases.62 , 63 Based on our review, prevalence of CVD was 8.9%, with HTN being the most prevalent in 33.1% across all groups (Table 1). This was also true in country specific evaluation, where HTN accounted for the leading portion of comorbidity in majority of regions (Fig 2), with only exceptions being Iran and South Korea where Diabetes and other CVD were the most common respectively. No clear association between fatality and CVD was found in our study, which is consistent with the uncertainty regarding comorbidities and mortality based on current understanding.10 , 53 , 55 A positive correlation was found; however, in a subset of pooled studies where HTN showed 1.65 more fatality risk in COVID-19 patients (Pool 2: Supplementary Table B). This result, however, needs careful evaluation due to limitations in sample size as well as inconsistency with other pooled analysis (Pool 1: Supplementary Table B) and other published studies.53 More extensive and detailed studies are needed to establish any clear association between CVD, HTN and any increased risk of fatality in COVID patients. Overall, strong consideration must be given in terms of management and treatment to COVID-19 positive patients presenting with preexisting cardiovascular comorbidity, especially uncontrolled blood pressure. Further, patients with unmanaged or uncontrolled hypertension should be informed on their respective risks and take appropriate preventative measures.

Diabetes mellitus (DM)

Globally, about half of a billion people are living with diabetes, one of most common comorbidities that can lead to multi-system complications.19 , 64 The long-term effect of elevated blood sugars results in a weakened immune system and increased susceptibility to infectious processes like COVID-19.65 Although, no clear association has been established between DM and COVID-19 severity, early investigations postulate a possible link with ACE2 overexpression in diabetic patients.65 Studies show that prevalence of diabetes varies from 4.5% in nonsevere cases upto 32% in severe complicated cases of COVID-19, with deaths seen in around 9.2% of all confirmed cases.3 , 66 , 67 Based on our study, diabetes (17.4%) was the most prevalent comorbidity seen in COVID-19 patients after hypertension (Table 1). And, in our country specific evaluation it was within the first 2 most common comorbidity across all regions, with Iran having it as the most prevalent comorbidity in their COVID-19 patient group (Fig 3). No clear association has been found regarding DM and mortality outcome in COVID-19 patients, as results from several published studies vary.66 , 67 We do not see any such correlation in our study either; however, in solely fatal cases it was seen to be highly prevalent (33.2%) comparable to HTN (35.2%) and CVD (34.9%) (Table 4). Given the complications of diabetes in weakening one's immune system, it is thus important to take precautionary measures to combat the high incidence of COVID-19 in this vulnerable group. Special focus must be given to proper glycemic control, blood glucose monitoring, and timely treatment to avoid the severe complications of COVID-19.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary syndrome (COPD)

The study on Global Burden of chronic Diseases (2016) indicates the prevalence of COPD to be 251 million cases globally leading to an estimated 3.17 million deaths in 2015.68 COPD is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects large and small airway tissues compromising their function in the long-term. The impact of respiratory infections on a chronically compromised respiratory system can lead to severe exacerbations, often causing fatal outcomes if not properly managed.69 Similar to other respiratory infections, COVID-19 primarily affects the lungs, invading the pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells.69 Recent histopathological studies on autopsy cases reveal features of the exudative and proliferative phases of diffuse alveolar damage and inflammatory infiltrate primarily consisting of alveolar macrophages and interstitial lymphocytes.70 , 71 Most often in severe cases this pathology leads to acute respiratory distress syndrome, one of the most serious complications of COVID-19.72 Surprisingly, studies show that COPD (1.5%-3%) is not as prevalent in COVID-19 cases compared to CVD and Diabetes.53 , 73 Similarly, mortality with COPD and COVID-19 is also lower than other major comorbidities (6.3% vs 10.5% CVD); although risk severity seems to be comparable (3-4 folds).53 , 69 Based on our review of data, prevalence of COPD (7.5%) in all cases as well as in fatal cases (13%) was higher compared to other studies, but still fell behind CVD and diabetes in overall prevalence (Tables 2 and 4). Besides Iran, which had COPD (18.6%) as the second most prevalent comorbidity in their COVID-19 patient group, all other countries had it as the third or fourth most common comorbidity (Fig 3). No clear association was found between COVID-19 mortality risk and COPD, which is consistent with other studies, although elevated mortality risk due to increased disease severity has been observed in other studies (Supplementary Table B).53 , 74 Although prevalence of COPD in COVID-19 cases seems to be low in fatal and nonfatal cases, risk of disease severity is relatively high, which can lead to substantial mortality rates. Effective preventative measures including added droplet precautions must be taken to reduce risk of infection in COPD patients, and immediate supportive treatment including ventilatory support should be available to mitigate the substantial disease severity.

Cancer

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide with an estimated 9.6 million deaths and prevalence of 17 million in 2018.75 Complications of underlying malignancy include a compromised immune system from disease process or treatment, among other multi-system defects.76 As with any infectious process this state of weakened immune system puts an individual at increased risk for COVID-19 susceptibility and severity.77 Studies show that the prevalence of cancer among COVID-19 patients range from 0.29% to 2%.76 , 77 And, mortality in these cases is estimated to be around 5%-7%.57 , 77 Based on our review, overall prevalence of cancer in COVID-19 patients was 2.6%, consistent with other studies, while prevalence in fatal cases was higher at 8.3% (Tables 2 and 4). Prevalence of cancer in COVID-19 patients was highest in the United Kingdom (12%) among the 7 countries that were reviewed; however, this data is limited by small sample size and source of data being from a long-term care facility. Overall, no clear correlation has been found between COVID-19 deaths and cancer, as is in our review (Supplementary Table B).76 However, focused study regarding cancer and COVID-19 outcomes seems to be lacking with limited data availability in current scientific literature. Therefore, despite low prevalence and limited scientific evidence in current literature, equal consideration must be given to cancer patients as with other comorbidities, given their degree of immunocompromised state. This is especially true with bone marrow transplant patients, hematological malignancies, and patients undergoing active chemo- or radiation treatments. As no current recommendations exist regarding withholding treatment from these patients, clinicians and patients must take early preventative measures to avert any potential complications.78

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Between 1990 and 2017, the prevalence of CKD increased by 29.3% and it became the 12th most common cause of death globally. Worldwide, 697.5 million cases of CKD are documented with 1.2 million death cases reported in 2017.79 Complications of CKD include a variety of metabolic, electrolyte, and cardiovascular derangements, which can cause severe outcomes, and are frequently exacerbated with AKI.80 The impact of CKD/AKI on COVID-19 patients is not well studied and limited data is available on the topic. Recent studies reporting on COVID-19 and AKI reveal that upto 30% of cases develop moderate to severe kidney injury.81 Although the apparent impact of COVID-19 on renal tissues is unclear, it is believed that the pathogenesis likely involves increased expression ACE2 in renal tissues, the main binding site for COVID-19.80 , 81 Prevalence of CKD in COVID-19 patients has been observed to be ranging from 1% to 2% in limited study groups. Based on our review, the prevalence of CKD was 3.5% in all cases and upto 9.6% in all fatal cases (Tables 1 and 4). Country specific review revealed the highest prevalence of CKD was in the United Kingdom (10.8%), but the data is limited by source and sample size as discussed above. There is limited data on COVID-19 fatality and CKD; with mortality data varying from 16% to 53%.82 , 83 No clear association was found between COVID-19 fatality and CKD (Supplementary Table B). Despite limited evidence on prevalence and severe outcomes, kidney injury seems to be substantial in COVID-19 patients.81 Therefore, standard precautionary measures must be followed given likely complications. Moreover, additional studies are needed on this topic to improve our understanding and to develop effective preventative and therapeutic strategies.

Others

Limited data and evidence are available for a variety of other chronic underlying comorbidities reviewed in this study (Table 2). Diseases in this category accounted for 15.5% of overall comorbidities and was seen in 11.6% of overall fatal cases (Tables 2 and 4). Interestingly, this group was the majority of comorbidity observed in COVID-19 patient data from Mexico (42.3%) (Fig 2). No clear evidence was found for any correlation between COVID-19 mortality and these conditions (Supplementary Table B). Overall, these conditions have low prevalence in COVID-19 cases; however, consist of a variety of diseases which cannot be concisely evaluated given the lack of specific data. Special consideration should be given to COVID-19 patients with particular conditions within this category including liver disease, transplant, immunocompromised, and hematological disorders as these conditions are associated with weakened immunity and severe complications.84

Limitations of study

Our study was limited by wide variation in sample size (25-7,497), availability of data, and quality of methodology in the included studies. Majority of the studies (18 out of 27) included in this study originated from China, which might limit the estimated contributions of comorbidities to COVID-19. However, overall patient sample size was comparable between 5/7 countries, and the pooled analysis consisted of data from multiple countries. Further, 2 studies report data from long-term care centers (Table 1), which might skew the comorbidity data; however, the combined sample size from these studies was low (268) compared to the composite sample size (22,753). Additionally, these studies were not included in any pooled analysis. This study includes a large composite sample size and encompasses major epicenters for COVID-19 with different social, cultural and ethnic backgrounds, which allows our result to be generalized. However, any conclusions drawn must be cautiously interpreted in the aforementioned contexts.

CONCLUSIONS

Since the breakout of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in the fall of 2019, health, social, and economic sectors around the world have suffered from persistent climb in cases and gruesome daily death tolls. Despite its rapid and impartial spread across different countries, ethnicities, gender, and age groups, within only a few months the medical and scientific community have come together in a global effort to characterize, evaluate, and manage this pandemic. Although vastly more studies and evidence need to be gathered, we have some clarity on vulnerable groups of people across the world who might have increased risk from acquiring COVID-19. These include individuals in higher age groups (>65), as well as those with one or more preexisting comorbid conditions.

This literature review explored the prevalence of top global comorbidities among individuals with COVID-19, as well as investigated any significant associations. We found higher prevalence of comorbid conditions in COVID-19 patients along with higher fatality in said group. We also found higher prevalence of HTN, CVD, and Diabetes in these groups as compared to COPD. Mortality in COVID-19 and having one or more comorbidity is still an uncertain topic, which is also evident in our findings. However, evidence of severity with comorbidity has been well documented in numerous studies. Given the limited level of evidence, more adequately powered studies are needed to further investigate these associations.

Overall, we have provided review on major comorbidities in the context on COVID-19 based on the most updated available literature. Knowledge on this topic is constantly changing and periodic updates may help aid in our ability to combat this global pandemic. This review corroborates findings from other studies in identifying vulnerable patient populations with comorbidities who are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 complications. Given this higher risk, it should thus be recommended that individuals with one or more underlying comorbidity take added precaution to avoid close contact with members of community, particularly in areas with high infection rates. Further, as effective anti-viral therapy and vaccinations are developed, strong consideration must be given towards focused intervention efforts to protect this vulnerable group. This review may support policy makers, clinicians, and researchers in making these informed decisions as new strategies are developed to overcome this pandemic.

Footnotes

Author contributions: K.T.B., B.B.B., S.B. together developed the concept of the study, searched the database, and extracted the data. B.B.B. and S.B. did the quality assessment of the papers. S.B. did the statistical analysis and drafted the results section. K.T.B., S.B., and B.B.B. had equal contribution in developing the initial manuscript draft. M.J.S. provided guidance in refining the concept, and revision of the manuscript. All the authors were involved in editing and finalizing the complete version of the manuscript.”

Conflict of interest: None to report.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.213.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health - The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harapan H, Itoh N, Yufika A, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(5):667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Age Sex. Existing Conditions of COVID-19 Cases and deaths. WorldoMeter. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 4.COVID-19 world map and mortality analysis. John Hopkins University. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oke J, Heneghan C. The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; 2020. Global Covid-19 Case Fatality Rates. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanche S, Lin Y, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1470–1477. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Predicting the next phase of the covid-19 epidemic: changes in human behavior. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 8.McIntosh K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology, virology, clinical features, diagnosis, and prevention. In:UpToDate. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Fang X, Cai Z, et al. Comorbid chronic diseases and acute organ injuries are strongly correlated with disease severity and mortality among COVID-19 patients: a aystemic review and meta-analysis. Research. 2020;2020:17. doi: 10.34133/2020/2402961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Y, Sun J, Dai Z, et al. Prevalence and severity of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Virol. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emami A, Javanmardi F, Pirbonyeh N, Akbari A. Prevalence of underlying diseases in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8:e35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.W-h Liang, W-j Guan, C-c Li, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 treated in Hubei (epicenter) and outside Hubei (non-epicenter): a nationwide analysis of China. European Respiratory J. 2020;55:2000562. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00562-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. CDC; February 12-March 28 2020 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the EU/EEA and the UK – eighth update. European Center for Disease Prevention and Control. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bommer W. CDC offers guidance to patients with chronic disease 'living with uncertainty' during COVID-19. Healio Rheumatology. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noncommunicable diseases . WHO; 2020. The Global Health Observatory. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Margulis AV, Pladevall M, Riera-Guardia N, et al. Quality assessment of observational studies in a drug-safety systematic review, comparison of two tools: the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and the RTI item bank. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:359–368. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S66677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao J, Tu WJ, Cheng W, et al. Clinical Features and Short-term Outcomes of 102 Patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa243. ;71:748-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. Bmj. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Q, Zheng Z, Zhang C, etal., Clinical characteristics of 145 patients with corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Taizhou, Zhejiang, China. Infection. 2020;48:543-551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen R, Liang W, Jiang M, et al. Risk factors of fatal outcome in hospitalized subjects with coronavirus disease 2019 from a nationwide analysis in China. Chest. 2020;1:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mo P, Xing Y, Xiao Y, etal. Clinical characteristics of refractory COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China [e-pub ahead of print], Clin Infect Dis. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa270, Accessed July 27, 2020

- 29.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020;75:1730–1741. doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang G, Hu C, Luo L, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 221 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. J Clin Virol. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J, Yu M, Tong S, Liu LY, Tang LV. Predictive factors for disease progression in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. J Clin Virol. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du Y, Tu L, Zhu P, et al. Clinical features of 85 fatal cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan. a retrospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1372–1379. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu K, Fang YY, Deng Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:1025–1031. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Wang L, Yan S, et al. Clinical characteristics of 25 death cases with COVID-19: A retrospective review of medical records in a single medical center, Wuhan. China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z, Yang B, Li Q, Wen L, Zhang R. Clinical features of 69 cases with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:769-777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J, et al. Epidemiological analysis of COVID-19 and practical experience from China. J Med Virol. 2020;92:755–769. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeong EK, Park O, Park YJ, et al. Coronavirus disease-19: The first 7,755 cases in the Republic of Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11:85–90. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.2.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang Y-J. Mortality rate of infection with COVID-19 in Korea from the perspective of underlying disease. Disaster Med Public Health Prepar. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Benelli G, Buscarini E, Canetta C, et al. SARS-COV-2 comorbidity network and outcome in hospitalized patients in Crema, Italy [e-pub ahead of print], medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.04.14.20053090, Accessed July 27, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Solís P, Carreňo H. COVID-19 fatality and comorbidity risk factors among confirmed patients in Mexico [e-pub ahead of print], medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.04.21.20074591, Accessed July 27, 2020

- 44.McMichael TM, Currie DW, Clark S, et al. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2005–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. Jama. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lovell N, Maddocks M, Etkind SN, et al. Characteristics, symptom management and outcomes of 101 patients with COVID-19 referred for hospital palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e77–e81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nikpouraghdam M, Jalali Farahani A, Alishiri G, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients in IRAN: A single center study. J Clin Virol. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, et al. The Socio-Economic Implications of the Coronavirus and COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao W, Li T. COVID-19: towards understanding of pathogenesis. Cell Res. 2020;30:367–369. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA. Care for critically Ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1499–1500. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.CDC . CDC; 2020. COVID-19 -Information for Pediatric Healthcare Providers. [Google Scholar]

- 52.One in Five People Globally Could be at Increased Risk of Severe COVID-19 Disease Through Underlying Health Conditions, 2020, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

- 53.Hong L., Shiyan C., Min L., Hao N., Hongyun L. Comorbid chronic diseases are strongly correlated with disease severity among COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Dis. 2020;11:668–678. doi: 10.14336/AD.2020.0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mertz D, Kim TH, Johnstone J, et al. Populations at risk for severe or complicated influenza illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verity R, Okell LC, Dorigatti I, et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:669–677. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.WHO; 2017. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs) [Google Scholar]

- 57.WHO Reports. World Health Organization; 2020. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vuorio A, Watts GF, Kovanen PT. Familial hypercholesterolaemia and COVID-19: triggering of increased sustained cardiovascular risk. J Intern Med. 2020;287:746–747. doi: 10.1111/joim.13070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of Cardiac Injury With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. COVID-19 and Cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;(20):1648–1655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mandal A. What happens when COVID-19 and cardiovascular diseases mix. Lifesciences. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schiffrin EL, Flack JM, Ito S, Muntner P, Webb RC. Hypertension and COVID-19. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:373–374. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The Global Health Observatory. WHO; 2020. World Health Statistics 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ma RCW., Holt RIG. COVID-19 and diabetes. Diabet Med. 2020;37:723–725. doi: 10.1111/dme.14300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Singh AK., Gupta R., Ghosh A., Misra A. Diabetes in COVID-19: prevalence, pathophysiology, prognosis and practical considerations. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang I., Lim MA., Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia - a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mathers CD., Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao Q, Meng M, Kumar R, et al. The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of COVID‐19: A systemic review and meta‐analysis. J Med Virol. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schaller T, Hirschbühl K, Burkhardt K, et al. Postmortem examination of patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:2518–2520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carsana L, Sonzogni A, Nasr A, et al. Pulmonary post-mortem findings in a series of COVID-19 cases from northern Italy: a two-centre descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1135-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Kim ES, Chin BS, Kang CK, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a preliminary report of the first 28 patients from the Korean Cohort Study on COVID-19. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e142. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alqahtani JS, Oyelade T, Aldhahir AM, et al. Prevalence, severity and mortality associated with COPD and smoking in patients with COVID-19: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cancer Research UK; 2018. Worldwide cancer statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Desai A, Sachdeva S, Parekh T, Desai R. Covid-19 and cancer: lessons from a pooled meta-analysis. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:557–559. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.ASCO Coronavirus Resources . 2020. American Society of Clinical Oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Collaboration GCKD. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395:709–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Batlle D, Soler MJ, Sparks MA, et al. Acute kidney injury in COVID-19: emerging evidence of a distinct pathophysiology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1380–1383. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sperati JC. John Hopkins Medicine Johns Hopkins University; 2020. Coronavirus: Kidney Damage Caused by COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oyelade T, Alqahtani J, Canciani G. Prognosis of COVID-19 in Patients with Liver and Kidney Diseases: An Early Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5:80. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5020080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Haybar H, Kazemnia K, Rahim F. Underlying chronic disease and COVID-19 infection: a state-of-the-art review. Jundishapur J Chronic Dis Care. 2020;9:e103452.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.