Abstract

Analyzing new nationwide data from the Understanding Society COVID-19 survey (N = 10,336), this research examines intersecting ethnic and native–migrant inequalities in the impact of COVID-19 on people’s economic well-being in the UK. The results show that compared with UK-born white British, black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) migrants in the UK are more likely to experience job loss during the COVID-19 lockdown, while BAME natives are less likely to enjoy employment protection such as furloughing. Although UK-born white British are more likely to reduce their work hours during the COVID-19 pandemic than BAME migrants, they are less likely to experience income loss and face increased financial hardship during the pandemic than BAME migrants. The findings show that the pandemic exacerbates entrenched socio-economic inequalities along intersecting ethnic and native–migrant lines. They urge governments and policy makers to place racial justice at the center of policy developments in response to the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Ethnicity, Economic impact, Inequality, Intersectionality, Migrant status, UK

1. Introduction

This research addresses two social developments that have swept the world in 2020. First, the COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on the global economy as well as individuals’ economic well-being (Ahmed, Ahmed, Pissarides, & Stiglitz, 2020). Second, the global rise of racism and anti-racism movements, often related to COVID-19 (Coates, 2020), has brought to the fore long-standing, entrenched ethnic inequalities (Li & Heath, 2016). Ethnic disparities in the health impact of COVID-19 are well documented across many countries (Bhala, Curry, Martineau, Agyemang, & Bhopal, 2020); most notably, COVID-19 infection and mortality rates are much higher among people from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups than their white counterparts. Yet insufficient attention has been paid to ethnic inequalities, or their intersections with native–migrant inequalities, in the economic impact of COVID-19 (Hooper, Nápoles, & Pérez-Stable, 2020; Laurencin & McClinton, 2020). To fill this gap, I analyze new nationwide data collected both before and after the pandemic in the UK. I ask how, if at all, the impact of COVID-19 on people’s economic well-being differs with their intersecting ethnic and migrant status. I take advantage of the longitudinal design of the dataset to capture the economic impact of the pandemic by tracing changes in people’s economic well-being before and during the pandemic.

2. Data and methods

2.1. Data and sample

I analyzed data from the Understanding Society (USOC) COVID-19 survey and preceding waves of the survey. Initiated in 2009, USOC is a nationally representative longitudinal panel survey, which has oversampled BAME and migrant groups (McFall, 2013). In April 2020, the first wave of the USOC COVID-19 survey collected data from 17,452 respondents during the UK’s national lockdown. While the regular USOC waves collect data from face-to-face interviews, complemented by mixed-mode techniques, the COVID-19 survey was administered through a self-completed questionnaire on the internet. Therefore, a sampling weight was provided by the USOC team to adjust for potential sample selection bias, which was used in all of my analyses.

To construct the analytical sample, I first eliminated respondents who did not have a valid record in Wave 9 of USOC, because I used data from the preceding wave to obtain key demographic information that was not collected in the COVID-19 survey. As I analyzed changes in people’s employment status, I limited the sample to respondents aged 20–65. Last, I deleted 1,377 cases with missing information on the variables used in the analysis. The final analytical sample contained 10,336 UK residents (“Full Sample”), of whom 8,281 were either self-employed or working as an employee in January–February 2020, before the COVID-19 outbreak in the UK (“Worker Sample”). See Online Supplements for detailed information on sample construction.

2.2. Economic well-being indicators

To provide relatively comprehensive coverage of the impact of COVID-19 on people’s economic well-being, I focused on five indicators. The descriptive statistics are presented in Appendix A and detailed information on measurement construction can be found in the Online Supplements.

2.2.1. Change in employment status

Based on people’s employment and furlough status in January–February and April 2020, I created a categorical variable to capture changes and continuity in people’s employment: “no change” (78 %), “lost job” (4%), and “furloughed” (18 %).

2.2.2. Change in working hours

Based on people’s working hours in January–February and April 2020, I created a categorical variable to capture changes and continuity in the respondents’ working time: “increased or no change” (53 %), “(partial) reduction in time” (16 %), and “total time loss” (31 %).

2.2.3. Household income loss

The survey asked the respondents to report whether their household had taken any measures to deal with income loss due to the pandemic. I created a dummy variable to distinguish whether a respondent took any action in response to household income loss (yes = 41 %).

2.2.4. Difficulty keeping up to date with bills

In Wave 9 (2017–2019) and the COVID-19 wave (April 2020) of USOC, the respondents reported whether they were up to date with various bills. The response categories were “up to date,” “behind with some bills,” and “behind with all bills.” Due to cell size consideration, I combined the latter two categories into “behind with bills” (7%). I used a dummy variable to capture whether people had found it more difficult to keep up to date with their bills during than before the pandemic.

2.2.5. Perceived financial hardship

In Wave 9 and the COVID-19 wave of USOC, the respondents were asked to describe their financial situation, which ranged from “living comfortably” through “doing alright,” “just about getting by” and “finding it quite difficult” to “finding it very difficult.” Due to cell size consideration, I combined the last two categories. I then created a dummy variable to capture whether a respondent found their financial situation more difficult during the pandemic than before (21 %).

2.3. Ethnic and migrant status

Based on whether one self-identified as a member of a BAME group and whether one was born in the UK, I distinguished the respondents’ intersectional ethnic–migrant status: “white, native” (88 %), “white, migrant” (5%), “BAME, native” (3%), and “BAME, migrant” (4%). Due to small sample sizes (see Online Supplements), I was not able to further distinguish specific ethnic groups.

2.4. Control variables

I controlled for a series of variables: age (and its quadratic term), gender, education, mode of employment before the pandemic (self-employment, zero hours contract, etc.), household composition, self-reported health, urban residency, long-term household income, occupational class (National Statistics Socio-economic Classification) and COVID-19 risk level; whether the respondents were key workers; whether they currently have or had ever reported COVID-19 symptoms or been tested for COVID-19; and whether they had received social benefits in January–February 2020. Marital status and region of residence were not included, as they were not statistically significantly associated with the outcome variables and their inclusion neither affected the key predictors nor helped to improve the overall model fit.

2.5. Analytical strategy

I fitted a series of binary, ordered and multinomial logit regression models for the distinct outcome indicators. Analysis of the first two outcome indicators was based on the Worker Sample and that of the other outcome indicators was based on the Full Sample. I estimated robust standard errors clustered at the household level to account for intra-household correlation. I graph predictive margins to present the findings, and the full regression results are presented in the Online Supplements.

3. Results

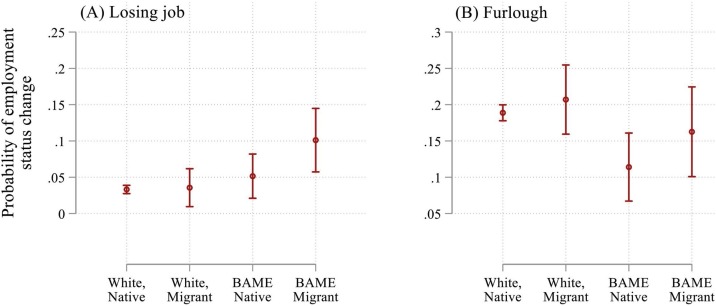

3.1. Employment status change

Fig. 1 presents the predicted probabilities of job loss (Panel A) and furlough (Panel B) during the COVID-19 lockdown. The results show the intersectional disadvantages faced by BAME migrants, who were 3.1 times more likely to lose their jobs during the COVID-19 lockdown than UK-born white British (10.1 % vs. 3.3 %, F [between-group difference] = 9.09, p < 0.01). Compared with BAME natives, UK-born white British were 1.7 times more likely to be furloughed (18.9 % vs. 11.4 %, F = 9.12, p < 0.01). While white non-migrant British were 5.7 times more likely to experience furlough than job loss (18.9 % vs. 3.3 %), the rate was as low as 1.4 times for BAME migrants (16.3 % vs. 11.4 %). These results, along with the results I report below, are after controlling for the fact that BAME groups are more likely to be self-employed and the self-employed tend to be more economically susceptible to the COVID-19 lockdown (Platt & Warwick, 2020).

Fig. 1.

Predicted probability of employment status changes during the pandemic.

Notes: N = 8,281. Error bars = 95 % confidence intervals.

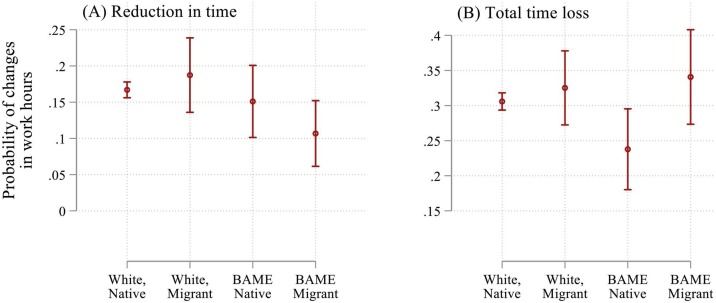

3.2. Work time change

Fig. 2 presents the probabilities of a partial reduction in work hours (Panel A) and total work time loss (Panel B) during the lockdown for those who were in work in January and February 2020. Compared with UK-born white British (16.7 %), BAME migrants were less likely to experience a reduction in their work hours during the lockdown (10.7 %, F = 6.36, p < 0.05). Moreover, BAME natives are less likely to experience total work time loss than their white non-migrant counterparts (23.8 % vs. 30.1 %, F = 5.08, p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Predicted probability of work-hour changes during the pandemic.

Notes: N = 8,281. Error bars = 95 % confidence intervals.

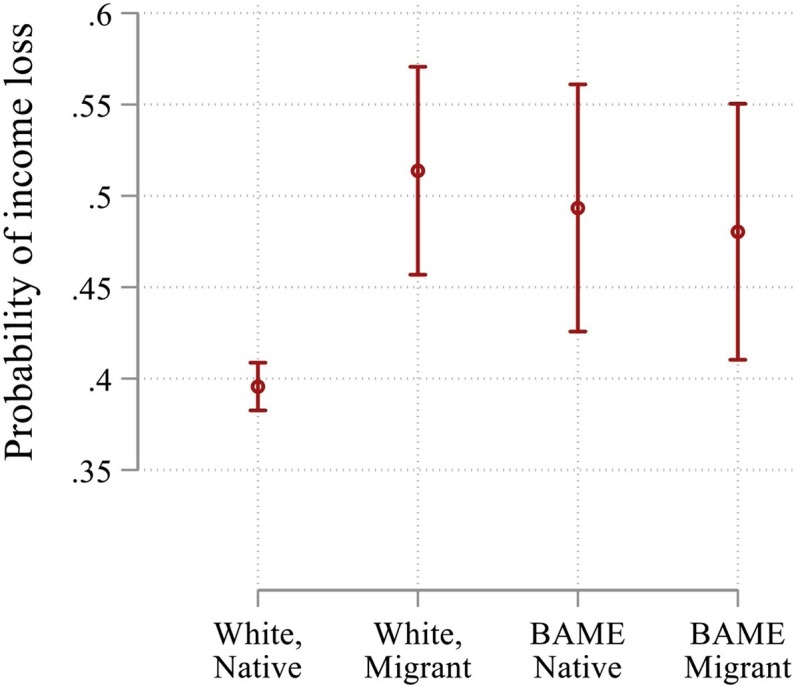

3.3. Household income loss

Fig. 3 presents the probability of household income loss during the pandemic. The results show that compared with UK-born white British (39.6 %), all BAME and migrant groups were more likely to experience household income loss during the pandemic, with income loss being 1.3 times (F = 16.48, p < 0.001), 1.2 times (F = 7.34, p < 0.01) and 1.2 times (F = 4.71, p < 0.05) more likely for white migrants (51.4 %), BAME natives (49.3 %) and BAME migrants (48.0 %), respectively.

Fig. 3.

Predicted probability of household income loss during the pandemic.

Notes: N = 10,336. Error bars = 95 % confidence intervals.

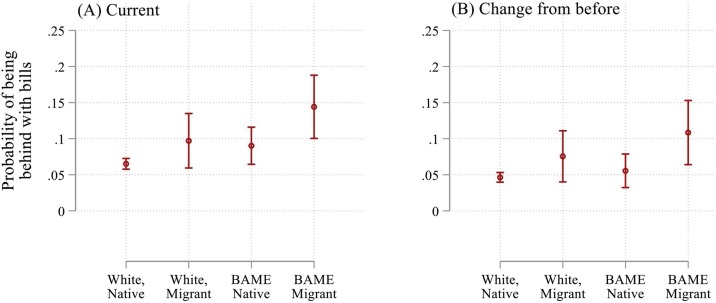

3.4. Falling behind with bills

Fig. 4 presents the probabilities of falling behind with bills (Panel A) and an increase in the difficulty of keeping up to date with bills during the COVID-19 lockdown (Panel B). The results in Panel A show that BAME migrants were 2.2 times (14.4 % vs. 6.5, F = 12.00, p < 0.001) more likely to report being behind with their bills than their white non-migrant counterparts during the COVID-19 lockdown. A similar pattern was observed for an increase in the difficulty of keeping up to date with bills during the lockdown compared with before, as shown in Panel B. Compared with UK-born white British (4.6 %), BAME migrants (10.8 %, F = 7.29, p < 0.01) were 2.3 times more likely to experience an increase in the level of difficulty of keeping up to date with their bills during the pandemic.

Fig. 4.

Predicted probability of being behind with bills during the pandemic and greater difficulty of paying bills during the pandemic than before.

Notes: N = 10,336. Error bars = 95 % confidence intervals.

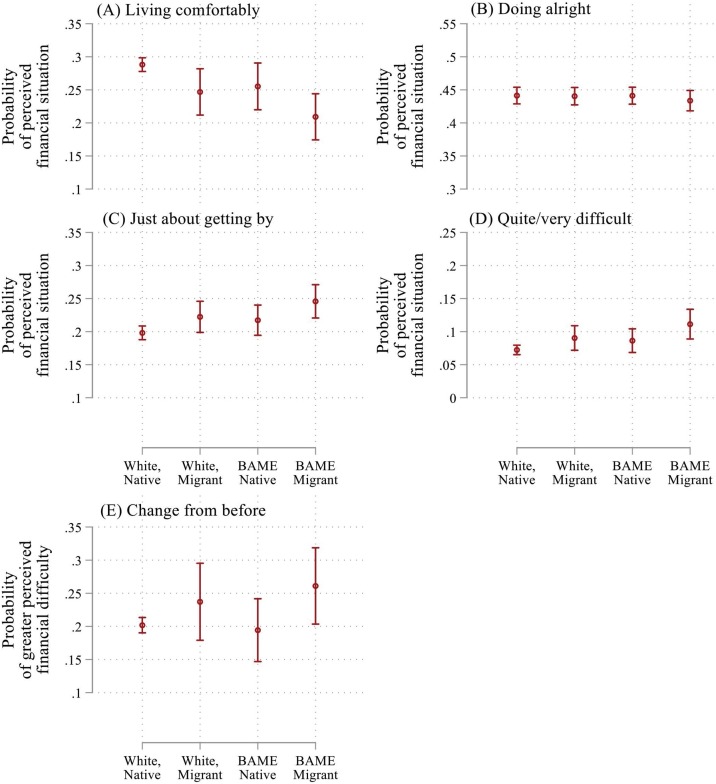

3.5. Perceived financial hardship

Fig. 5 presents people’s self-reported financial situation (Panels A–D) and the probability of a worsened financial situation during the pandemic (Panel E). The results show that compared with UK-born white British, BAME migrants were less likely to report living comfortably but more likely to report experiencing financial difficulty. Specifically, UK-born white British (28.8 %) were 1.4 times more likely than BAME migrants (20.9 %) to report leading a financially comfortable life during the pandemic (F = 19.37, p < 0.001). In contrast, BAME migrants (11.1 %) were 1.5 times more likely than their white non-migrant counterparts (7.2 %) to report experiencing financial difficulty during the pandemic (F = 12.34, p < 0.001). As shown in Panel E, BAME migrants (26.6 %) were 1.3 times more likely than their white non-migrant counterparts (20.2 %) to experience an increase in their perceived level of financial hardship during the COVID-19 lockdown (F = 3.90, p < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Predicted probability of self-reported financial situation during COVID-19 and worsened financial situation during compared with before COVID-19.

Notes: N = 10,336 respondents. Error bars = 95 % confidence intervals.

4. Conclusions

As we enter the third decade of the 21st century, the COVID-19 pandemic and the global rise of racism and anti-racism movements are two of the most prominent developments to define people’s lives around the world. These two developments are inextricably entangled (Bhala et al., 2020). In 2018, compared with their white colleagues doing the same work, BAME employees suffered a wage shortfall of £3.2 billion in the UK (Topham, 2018). My findings uncover intersecting ethnic and native–migrant inequalities in the impact of COVID-19 on people’s economic well-being, which exacerbate entrenched socio-economic disadvantages faced by BAME migrants in the UK (Li & Heath, 2016, 2020). These inequalities are evident in the negative impact of COVID-19 on people’s employment status, maintenance of income, ability to keep up to date with bills, and self-perceived financial situation in the UK. Taken together, my findings underline the importance of considering social groups living at the intersection of multiple margins of society (Collins & Bilge, 2020), as the pandemic and associated lockdown have had a particularly severe impact on the economic well-being of BAME migrants in the UK. My findings not only illustrate the much more severe economic adversity facing BAME migrants than UK-born white British during the pandemic, but also indicate that BAME natives seem to enjoy a lower level of employment protection, such as furloughing, than their white non-migrant counterparts.

In future research, it will be important to trace whether ethnic and native–migrant inequalities in the impact of COVID-19 on people’s economic well-being worsen as the pandemic develops. As many countries start to ease and lift lockdown measures, it will also be crucial to examine intersectional inequalities in people’s long-term trajectory of (economic) recovery. Furthermore, this research urges policy makers and practitioners to develop initiatives not only to protect members of BAME and migrant groups from the adverse economic impact of the pandemic, but also to ensure racial justice as well as broader social justice (Kristal & Yaish, 2020; Qian & Fan, 2020) in the design and delivery of social protection and welfare provision during these challenging times.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments from the anonymous reviewer. The data used in this research were made available through the UK Data Archive. The United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Survey is an initiative funded by the ESRC and various Government Departments and the Understanding Society COVID-19 survey is funded by the UKRI, with scientific leadership by the ISER, University of Essex, and survey delivery by NatCen Social Research and Kantar Public. Neither the original collectors of the data nor the Archive bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100528.

Appendix A. Sample characteristics

| All (N = 10,336) |

Worker (N = 8,281) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean/proportion | ||

| Ethnic × migrant statusa | ||

| White, native | .88 | .88 |

| White, migrant | .05 | .05 |

| BAME, native | .03 | .03 |

| BAME, migrant | .04 | .04 |

| Economic well-being | ||

| Employment-status change | ||

| No | — | .78 |

| Job loss | — | .04 |

| Furlough | — | .18 |

| Work-hour change | ||

| No change or increased | — | .53 |

| Partial reduction | — | .16 |

| Total time loss | — | .31 |

| Household income loss a | .41 | .43 |

| Behind with bills a | .07 | .06 |

| Increasing difficulty with paying bills | .05 | .04 |

| Financial situation a | ||

| Living comfortably | .28 | .28 |

| Doing alright | .44 | .46 |

| Just about getting by | .20 | .19 |

| Quite/very difficult | .07 | .07 |

| Increase in financial hardship | .21 | .20 |

| Control variables | ||

| Age a | 45.17 | 44.19 |

| Age (standard deviation) | (12.15) | (11.53) |

| Female a | .54 | .52 |

| Education c | ||

| No or other | .17 | .15 |

| GCSE | .18 | .18 |

| A-level | .23 | .22 |

| Higher degree | .42 | .45 |

| Mode of employment b | ||

| Fixed hours | .54 | .68 |

| Flexible hours | .07 | .09 |

| Employer assigned hours (e.g., zero hours contract) | .07 | .08 |

| Self-employed | .12 | .15 |

| Not employed | .20 | — |

| Key worker a | .36 | .44 |

| Household composition a | ||

| One adult, no child | .09 | .08 |

| One adult, at least one child | .03 | .03 |

| Multiple adults, no child | .49 | .48 |

| Multiple adults, at least one child | .38 | .41 |

| COVID-19 at-risk population a | ||

| Low | .78 | .81 |

| High | .18 | .16 |

| Very high | .04 | .03 |

| COVID-19 tested or symptoms a | .14 | .15 |

| Self-reported health c | ||

| Excellent | .12 | .13 |

| Very good | .37 | .40 |

| Good | .33 | .34 |

| Fair | .13 | .11 |

| Poor | .05 | .02 |

| Long-term household income quintile c | ||

| 1st (lowest) | .21 | .17 |

| 2nd | .21 | .21 |

| 3rd | .20 | .21 |

| 4th | .19 | .21 |

| 5th (highest) | .19 | .21 |

| Occupational class (National Statistics Socio-economic Classification) c | ||

| Semi-routine and routine | .18 | .21 |

| Lower supervisory and technical occupation | .06 | .07 |

| Small employers and own account workers | .07 | .08 |

| Intermediate | .11 | .13 |

| Managerial, administrative, and professional | .35 | .41 |

| Not applicable (unemployed, inactive, etc.) | .23 | .10 |

| Received social benefits b | .17 | .11 |

| Urban residency c | .77 | .77 |

Note: BAME = black, Asian and minority ethnic. GCSE = General certificate of secondary education. Key worker = critical workers such as medical staff. Weighted statistics. See Online Supplements for detailed measurement information.

a April 2020. b Reported in April 2020 referring to January–February 2020. c Reported in previous waves.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ahmed F., Ahmed N., Pissarides C., Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e240. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30085-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhala N., Curry G., Martineau A.R., Agyemang C., Bhopal R. Sharpening the global focus on ethnicity and race in the time of COVID-19. The Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1673–1676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31102-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates M. Covid-19 and the rise of racism. The British Medical Journal. 2020:369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P.H., Bilge S. John Wiley & Sons; London: 2020. Intersectionality. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper M.W., Nápoles A.M., Pérez-Stable E.J. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kristal T., Yaish M. Does the coronavirus pandemic level gender inequality curve? (It doesn’t) Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2020;68:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurencin C.T., McClinton A. The COVID-19 pandemic: A call to action to identify and address racial and ethnic disparities. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00756-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Heath A. Class matters: A study of minority and majority social mobility in Britain, 1982–2011. The American Journal of Sociology. 2016;122(1):162–200. doi: 10.1086/686696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Heath A. Persisting disadvantages: A study of labor market dynamics of ethnic unemployment and earnings in the UK (2009–2015) Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2020;46(5):857–878. [Google Scholar]

- McFall S.L., editor. Understanding society—UK household longitudinal study, user manual. University of Essex; Colchester: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Platt L., Warwick R. The ISF deaton review. 2020. Are some ethnic groups more vulnerable than others?www.ifs.org.uk/inequality/are-some-ethnic-groups-more-vulnerable-to-covid-19-than-others/ Accessed on June 12, 2020: [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y., Fan W. Who loses income during the COVID-19 outbreak? Evidence from China. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2020;68:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Topham G. The Guardian; 2018. £3.2Bn UK pay gap for black, Asian and ethnic minority workers.www.theguardian.com/money/2018/dec/27/uk-black-and-ethnic-minorities-lose-32bn-a-year-in-pay-gap Accessed on June 12, 2020: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.