Abstract

BACKGROUND

Intrawound vancomycin powder (VP) has been rapidly adopted in spine surgery with apparent benefit demonstrated in limited, retrospective studies. Randomized trials, basic science, and dose response studies are scarce.

PURPOSE

This study aims to test the efficacy and dose effect of VP over an extended time course within a randomized, controlled in vivo animal experiment.

STUDY DESIGN/SETTING

Randomized controlled experiment utilizing a mouse model of spine implant infection with treatment groups receiving vancomycin powder following bacterial inoculation.

METHODS

Utilizing a mouse model of spine implant infection with bioluminescent Staphylococcus aureus, 24 mice were randomized into 3 groups: 10 infected mice with VP treatment (+VP), 10 infected mice without VP treatment (No-VP), and 4 sterile controls (SC). Four milligrams of VP (mouse equivalent of 1 g in a human) were administered before wound closure. Bioluminescence imaging was performed over 5 weeks to quantify bacterial burden. Electron microscopy (EM), bacterial colonization assays (Live/Dead) staining, and colony forming units (CFU) analyses were completed. A second dosing experiment was completed with 34 mice randomized into 4 groups: control, 2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg groups.

RESULTS

The (+VP) treatment group exhibited significantly lower bacterial loads compared to the control (No-VP) group, (p<.001). CFU analysis at the conclusion of the experiment revealed 20% of mice in the +VP group and 67% of mice in the No-VP group had persistent infections, and the (+VP) treatment group had significantly less mean number of CFUs (p<.03). EM and Live/Dead staining revealed florid biofilm formation in the No-VP group. Bioluminescence was suppressed in all VP doses tested compared with sterile controls (p<.001). CFU analysis revealed a 40%, 10%, and 20% persistent infection rate in the 2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg dose groups, respectively. CFU counts across dosing groups were not statistically different (p=.56).

CONCLUSIONS

Vancomycin powder provided an overall infection prevention benefit but failed to eradicate infection in all mice. Furthermore, the dose when halved also demonstrated an overall protective benefit, albeit at a lower rate.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Vancomycin powder is efficacious but should not be viewed as a panacea for perioperative infection prevention. Dose alterations can be considered, especially in patients with kidney disease or at high risk for seroma.

Keywords: Biofilm, Infection, Surgical site infection, Vancomycin powder

Introduction

Spine implant infections (SII) are devastating complications which can lead to neurologic compromise, sepsis, and death. Despite perioperative infection prophylaxis, postoperative spine infections persist at a rate of 0.7% to 10% following elective spine surgery [1]. These infections can result in significant morbidity to the patient and cost to the healthcare system with increased lengths of stay, higher readmission rates, and total costs escalating to about $1,000,000 per case [2–5].

Intrawound vancomycin powder (VP) administration before wound closure has been rapidly adopted in spine surgery. Within the clinical literature, VP has been demonstrated as a safe and effective prophylactic modality to prevent SII in retrospective studies with the majority of studies reporting reduced infection rates with minimal complications [5,8–17]. However, reports of gram-positive infections despite VP application, complications including ototoxicity, seroma formation, and renal injury, and no infection rate difference in the only randomized, clinical trial regarding this practice presents challenging data [8–10,13,16–19].

Within two animal model studies, VP administration resulted in 100% eradication of Staphylococcus aureus within a rabbit spine infection model and rat periprosthetic joint infection model following animal sacrifice and culture at four and six days, respectively [6,7]. The study of implant-associated infection is fraught with challenges as biofilm associated infection can be insidious and difficult to diagnose, hover below detection levels in many assays, and require an incubation period on the order of several days to weeks. As such, longitudinal, non-invasive modeling of implant infection has proven ideal as low-level bacterial contamination can be identified over time as biofilms reach a steady state with planktonic bacteria detachment and dispersal [20].

Given its highly prevalent application in the context of scarce preclinical and mixed clinical evidence, further investigation regarding the efficacy, safety, and dose effect of VP is warranted. Utilizing a previously established mouse model of SII which enables longitudinal modeling of biofilm infections, we aimed to study the efficacy and dose effect of intrawound vancomycin powder.

Materials and methods

Statement of ethics

Animals utilized in this study were treated in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act (AWA), 1996 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, PHS Policy for the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and policies set forth in the UCLA Animal Care and Use Training Manual. The UCLA Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee (ARC# 2012–104) approved the completion of this study.

Bioluminescent bacteria and an in vivo mouse model of spine implant infection

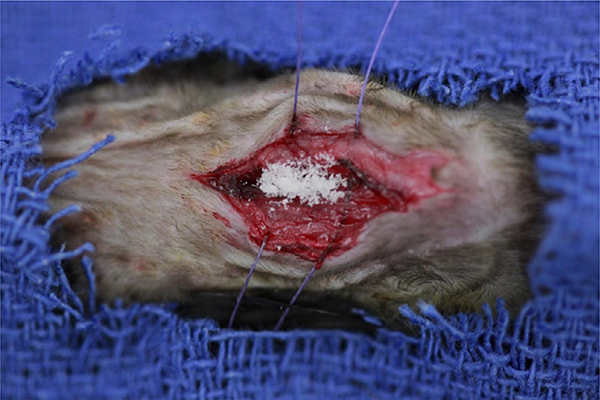

The following is a summary from the previously published description of the in vivo mouse model of spine implant infection [21]. A bioluminescent strain of S. aureus (Xen36, PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA) was incubated, purified, washed, and diluted to the desired inoculum (1×103 colony forming units [CFU] in 2 mL PBS). Twelve-week-old C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were subjected to survival surgery in which a 0.1 mm diameter L-shaped stainless-steel implant is transfixed into the lumbar spine. Following placement of the implant, 1×103 CFUs of bioluminescent Xen 36 S. aureus was inoculated directly onto the implant. Depending on randomization, the wound was either closed immediately (no treatment) or administered an intrawound dose of vancomycin powder (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Four milligram of vancomycin powder applied to the surgical dissection wound overlying the lumbar spine within the mouse model of spinal implant infection.

Study design

In the first experiment testing the standard dose of vancomycin powder, 24 mice were randomized into VP treatment with bacterial inoculation (+VP), no VP treatment with bacterial inoculation (No-VP), and sterile control with no VP treatment (SC) groups in numbers of 10, 10, and 4 mice, respectively. In the second experiment testing varying doses, 34 mice were randomized into either a 2 mg VP (n=10), 4 mg VP (standard dose, n=10), 8 mg VP (n=10), or no VP control group (n=4).

Vancomycin powder: dosing calculation

The most commonly accepted standard dose of intrawound vancomycin powder for human use is 1 g. Utilizing previously described equivalent body surface area dosage conversion factors, the dose for a mouse is the human dose (1 g/60 kg) multiplied by a factor of 12 [22]. The mice used in this experiment weighed 0.02 kg (20 g) to yield a dose of 0.004 g or 4 mg. The dosing experiment then doubled and halved the standard 4 mg mouse VP dose, yielding experimental groups of 2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg of VP representing human equivalent doses of 500 mg, 1 g, and 2 g, respectively.

Bioluminescence and optical imaging

Consistent with previously described methods [21], in vivo bioluminescence imaging was performed using an IVIS Lumina II (PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA) on postoperative dates (POD) 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 18, 21, 25, 28, and 35 to quantify bacterial burden over time. Data are presented via color scale overlaid on a gray-scale photograph of mice and quantified as mean maximum flux (photons per second (s) per cm2 per steradian (sr) [p/s/cm2/sr]) within a circular region of interest (16,103 pixels) using Living Image software (PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA).

Quantification of S. aureus bacteria on implant and surrounding tissue with CFU counts

Bacteria adherent to the implant and surrounding tissue were cultured and quantified at the conclusion of the experiment. The implant was sonicated in 1 mL 0.3% Tween-80 in TSB, and surrounding tissue was homogenized (Pro200H Series homogenizer; Pro Scientific) in order to isolate bacteria. Bacteria from both samples were then cultured overnight and quantified.

Visualization of biofilm with variable pressure scanning electron microscopy (VP-SEM)

Two implants from the (+VP) and (No-VP) groups were harvested at the conclusion of the experiment to qualitatively inspect implants for biofilm formation. The whole extent of the implant was visualized using a field emission variable-pressure scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM Zeiss Supra VP 40). Topographical characteristics of the surface were visualized to assess for extracellular polymeric substances matrices.

Live/Dead cell viability assay to visualize bacteria

To visualize viable bacteria on implants, Live/Dead assays (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Canoga Park, CA) were completed on two spinal implants from the (+VP) and (No-VP) groups at the conclusion of the experiment. This assay was completed immediately upon animal sacrifice at the conclusion of the experiment, and pins were prepared and analyzed immediately, per Thermo Fischer protocol. As described within the Thermo Fischer protocol, fluorescent dyes that bind to living and dead bacterial cell walls and organelles were applied to the implants. When placed under a fluorescent, confocal microscope, green and red fluorescence was indicative of living and dead bacteria, respectively.

Power analysis and statistical analysis

As previously reported, each experimental arm had at least 6 mice/group to adequately power the study to attain statistical significance set at p<.05 level [23]. For longitudinal bioluminescence data, statistical analysis was under-taken with a linear mixed-effects regression model to determine the effect of vancomycin powder on bioluminescence/bacterial burden over all time points. Student’s t test (one- or two-tailed where indicated) was utilized for comparison of continuous variables. Pearson chi-square analysis was utilized for comparison of categorical variables. Data were expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). All statistical analyses were performed using Stata-14 software (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Source of funding

This study was generously supported in part by the National Institutes of Health and the H H Lee Research Program.

Results

Experiment 1: Efficacy of vancomycin powder

Comparison of in vivo bioluminescence and corresponding CFUs of infected mice treated with and without vancomycin powder

The group of infected mice treated with vancomycin powder (+VP) exhibited significantly less bacterial bioluminescent signal compared with the group of infected mice without vancomycin powder treatment (No-VP) (p<.001). The bacterial bioluminescent signal curves of the (No-VP) group were consistent with historical infection curves [21]. The mean bioluminescence for the (+VP) group did not reach levels greater than baseline flux or 8.84× 104 p/s/cm2/sr (Fig. 2).

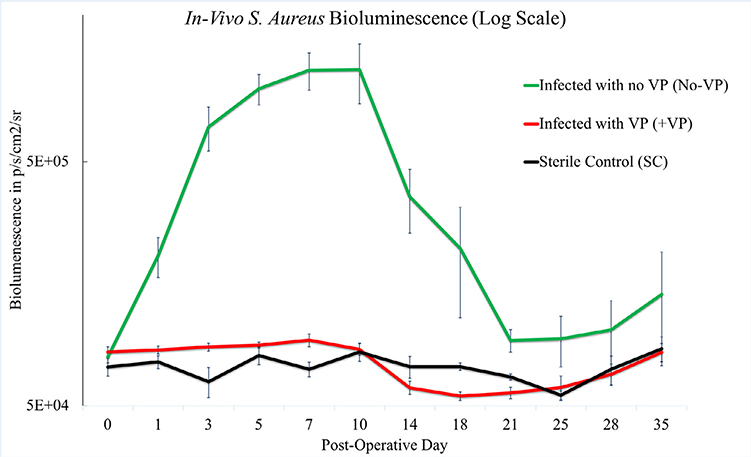

Fig. 2.

In vivo bioluminescent signal by p/s/cm2/sr over time representing bacterial burden. The bioluminescent signal of the infected mice treated with VP (+VP) was suppressed and statistically different than the infected mice without VP treatment (No-VP), (p<.001). The (No-VP) bioluminescent signal on day 35 was higher than that of (+VP) & (SC) indicating a persistent infection. The +VP group was indistinguishable from the sterile mice who did not receive bacterial inoculum.

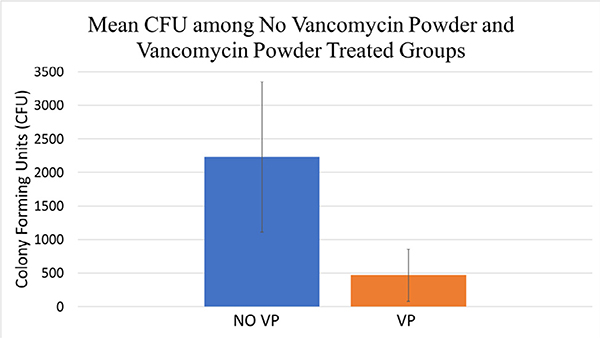

The results of bioluminescent imaging were supported by CFU quantification from the implant and surrounding tissue taken at POD 35. The mean CFU/mL for the No-VP and +VP group were 2200 and 470 CFU/mL, respectively (p=.02; Fig. 3). Mice subjected to CFU quantification revealed that 70% (7 out of 10) of mice within the No-VP group established a chronic high-level infection, and 20% (2 out of 10) within the +VP group established a chronic infection.

Fig. 3.

The average bacterial colony forming units (CFU) from the implant and surrounding tissue among vancomycin powder treated (+VP) and no treatment (No-VP) groups were analyzed at the conclusion of the experiment. The CFU enumeration was significantly lower in the vancomycin powder treatment (+VP) group (4.7*102 CFUs) compared to the no VP treatment (No-VP) group (2.2× 103 CFUs), (p=.02).

Variable pressure scanning electron microscopy

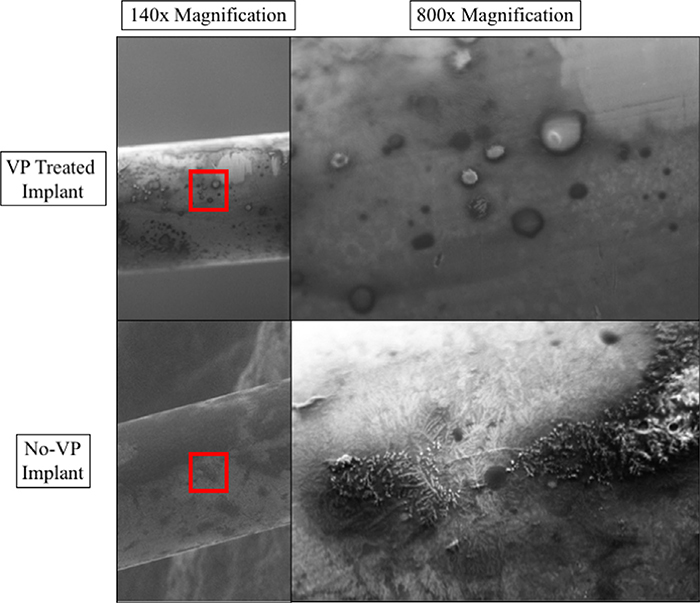

Variable pressure scanning electron microscopy (VP-SEM) imaging of implants from (+VP) and (No-VP) mice were analyzed. The (+VP) group revealed cellular debris without evidence of biofilm, whereas the (No-VP) implants were coated with biofilm (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Variable pressure scanning electron microscope images of an implant from the vancomycin treated group (+VP) in the top panel. Top left panel (A) reveals an image of the whole diameter of the pin, where inspection at a higher magnification revealed cellular debris (B) and tissue without characteristic biofilm along the entire pin. Bottom left panel (C) reveals an image of the whole diameter of the infected pin without VP treatment (No-VP), where inspection at higher magnification revealed biofilm coating throughout the implant (D).

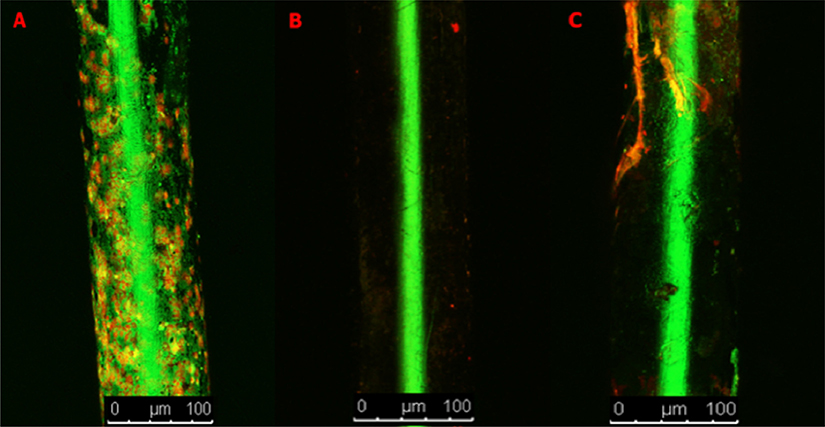

Live/Dead staining

Implants from the No-VP and +VP groups were subjected to Live/Dead Cell Viability Assays. Upon inspection of the pins from the No-VP group, abundant green and red staining along the implant was visualized indicative of robust bacterial adherence (Fig. 5A). Upon inspection of the implants from the +VP group, an implant from a mouse with elevated bioluminescence levels and nonelevated bioluminescence levels were analyzed. The implant with nonelevated bioluminescence revealed no staining (Fig. 5B). The implant with mildly elevated bioluminescence positively stained for the presence of bacteria, although it stained to a much lesser degree compared with the No-VP implants (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

A-D. Stainless steel implant pins subjected to Live/Dead staining to test for live and dead bacterial matter. (A) Pin from an implant inoculated with bacteria with no VP treatment. (B) Pin from an implant inoculated with bacteria and treated with VP. (C) Pin from an implant inoculated with bacteria and treated with VP which on bioluminescence revealed a low level chronic infection.

Experiment 2: Dose effect of vancomycin powder

Comparison ofin vivo bioluminescence and corresponding CFUs of infected mice treated with 2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg of VP

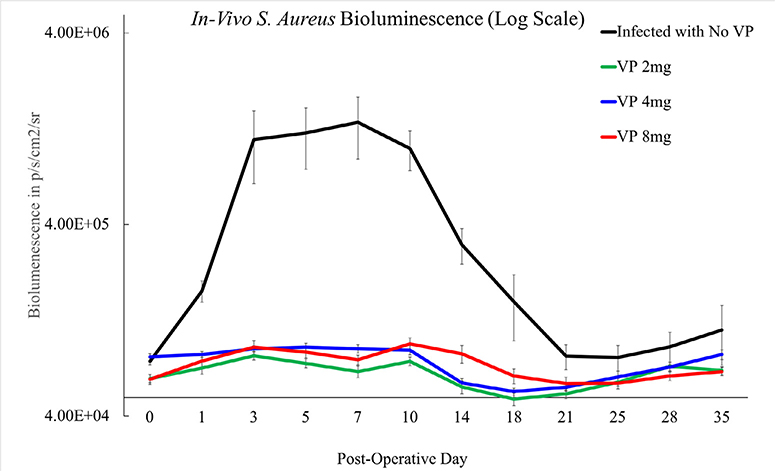

The 2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg dosing groups each revealed significantly less bacterial burden over time compared with infected mice without any VP treatment (p<.001). The bacterial bioluminescent signal curves of the (No-VP) group were consistent with historical infection curves (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

In vivo bioluminescent signal by p/s/cm2/sr over time representing bacterial burden. The bioluminescent signal of the infected mice treated with 2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg of VP were suppressed and statistically different than the infected mice without VP treatment, (p<.001). The group of mice without VP treatment exhibited a bioluminescent signal on day 35 that higher than that of the varying dosing groups indicating a persistent infection.

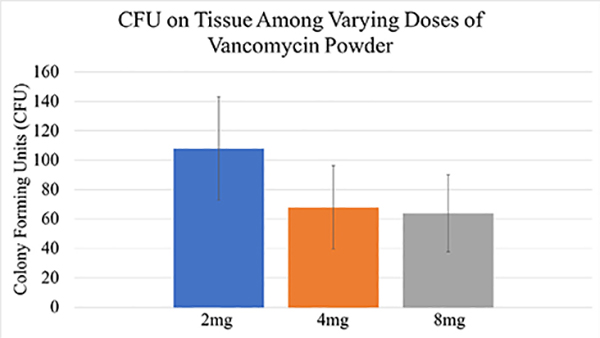

The results of bioluminescent imaging were supported by CFU quantification from the implant and surrounding tissue taken at POD35. The mean CFU/mL for the 2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg groups were 110, 70, and 68, respectively (p=.56; Fig. 7). One hundred percent (4 of 4) of mice established an infection in the no VP infected group, and 40% (4 of 10) mice established an infection in the 2 mg group, 10% (1 of 10) in the 4 mg group, and 20% (2 of 10) mice in the 8 mg group. Differences in rates of infection between the 2 mg vs. 4 mg, (Pearson chi-square test, p=.121), 2 mg vs. 8 mg (Pearson chi-square test, p=.329), and 4 mg vs. 8 mg (Pearson chi-square test, p=.53) failed to reach statistical significance.

Fig. 7.

The average bacterial colony forming units (CFU) from the implants and surrounding tissue of mice among the varying dosing groups (2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg) were analyzed at the conclusion of the experiment. The varying dosing groups were not statically different from one another (p=.56).

Complications

Three of 10 mice within the 8 mg VP dosing group developed severe exfoliative dermatitis that was treated with topical medication. No other mice developed this complication.

Discussion

This animal model study lends support to the practice of vancomycin powder (VP) administration in spine surgery. These data suggest that the overall effect of vancomycin powder is protective against implant infection and biofilm formation. However, VP treatment alone was unable to prevent infection in all mice, contrary to previous animal studies. With regard to dosing, there was no statistical difference in bacterial proliferation when the dose was halved or doubled.

Within spine surgery, vancomycin powder application has been rapidly adopted. The clinical literature is largely in favor of VP application in spine surgery with a few significant exceptions. Retrospective data and meta-analyses have reported reduced infection rates and relatively few complications with the use of VP in spine surgery [5,8–17]. However, there are exceptions including the Martin et al. retrospective comparative analyses of posterior cervical and deformity cohorts that failed to show a difference, and the sole randomized, controlled clinical trial by Tubaki et al. also failed to reveal a difference in infection rates [9,18,24]. Furthermore, perioperative and late-onset infections with vancomycin susceptible organisms occur in the setting of VP use with high frequency [9,10,13,16,17,28,29]. As such, VP application should not be viewed as a panacea to bacterial inoculation of implants during surgery, and efforts to maintain sterility may necessitate vigilance well prior to surgical incision during implant processing [30].

With regard to the basic science investigations, previous animal investigations testing VP have reported 100% eradication of bacterial infection. Vancomycin powder has been studied in a rabbit model of spine infection in which preoperative cefazolin vs. preoperative cefazolin with intrawound VP was tested [6]. On postoperative day 4, the animals were sacrificed for bacterial counts and the authors concluded that the combination treatment of cefazolin with VP eradicated surgical site contamination. Within a rat model of arthroplasty infection, the combination of preoperative vancomycin and VP completely eliminated infection based on bacterial enumeration 6 days following inoculation [7]. The results presented in this study support the protective effect of VP, although persistent infection occurred in a minority of VP treated mice, consistent with acute infections seen in the clinical setting despite VP treatment. The sensitivity of this study’s model and ability to mimic the human environment may be increased in comparison to previous models for the following reasons: (1) multiple endpoints to quantify bacterial burden, (2) time-course of 35 days to allow for persistent bacteria to amplify, and (3) time course to allow for the establishment of biofilm.

Implant infection is a dynamic process that is difficult to treat and study. The aforementioned animal studies independently posited that delayed, long-term infections could not be studied given that animals were sacrificed within 1 week of bacterial inoculation. The process of animal sacrifice, sample preparation, culture, and CFU enumeration may lack the sensitivity to detect small quantities of resistant or implant-adherent bacteria, a concept known as the microbacterial Limit of Detection [25]. A widely accepted rationale for the in vivo or clinical shortcomings of many in vitro supported infection treatments is the lack of sensitivity to identify small quantities of recalcitrant or persistent bacteria. The importance of longitudinal study of infection treatments to allow for persistent bacteria to repopulate has been demonstrated, and study conclusions can be greatly affected by the timing of bacterial assay [20]. As such, the composite data of this longitudinal study with bioluminescence data, CFU analysis, VP-SEM, and Live/Dead staining support the notion that VP treatment prevents infection in the majority, but not all treated mouse subjects.

The overall protective effect of VP persisted when the dose was halved and doubled, equating to doses of 500 mg or 2,000 mg in a human. The bioluminescence curves of all doses were significantly suppressed compared with untreated, infected mice, and bacterial cultures from the implants and surrounding tissue were not significantly different across dosing groups. Interestingly, the infection rates of 1/2 dose, standard-dose, and double-dose varied at 40%, 10%, and 20%, respectively, although these rates were not statistically different (Pearson chi-square coefficient, p=.121). The administration of high-dose VP resulted in exfoliative dermatitis for three mice. Exfoliative dermatitis has been seen in patients with end-stage renal disease receiving parenteral vancomycin [26,27]. Local, intrawound VP administration for spine surgery does confer risk of complications with reports of seroma formation, nephropathy, and ototoxicity [13]. In order to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity, consideration may be given to decreasing the dose of VP administration in patients with renal disease as this study lends evidence to the efficacy of lower doses of VP.

The principle limitation of this study is that the surgical technique of inoculation and subsequent VP administration represents the optimal condition of use for VP, which could positively bias our result. In the clinical setting, large operative fields of the spine potentially remain open for prolonged periods, and the subsequent effect this has on bacterial contamination and VP application before wound closure may not be adequately modeled in this experiment. This study investigated vancomycin’s effects against methicillin-sensitive S. aureus and may not be generally applicable to other organisms. Furthermore, VP may provide selective pressures toward vancomycin-resistant organisms, which was not studied in this experiment. The nature of this mouse model investigation and the omission of IV preoperative antibiotics from this study’s experimental protocol may not replicate the exact clinical scenario. However, this study’s aim was to assess VP as an independent, isolated variable to provide scientifically heuristic evidence with regard to its efficacy and dose effect. Future directions for this study may include the study of other organisms such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, Propionibacterium acnes, and methicillin-resistant S. aureus. In addition, RNA sequencing of surviving S. aureus colonies may reveal the degree to which VP administration selects for vancomycin resistance, a potentially harmful outcome.

Despite these limitations, we believe this animal model investigation contributes to the body of evidence regarding vancomycin powder use in spine surgery. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first animal investigation examining the long term and dose effects of VP. By studying the course of infection over 5 weeks, this in vivo study lends support to the application of VP at varying doses while illuminating its limitations, namely, its inability to eradicate all cases of infection despite direct application over bacterial inoculums.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service award T32AR059033 and award 5K08AR069112-0. Further support was provided by the H H Lee Research Program.

Author disclosures: HYP: Grant: H H Lee (C); Fellowship Support: NIH (E). VH: Nothing to disclose. SDZ: Nothing to disclose. WS: Nothing to disclose. CH: Nothing to disclose. RAS: Nothing to disclose. MMS: Nothing to disclose. JDP: Nothing to disclose. JH: Nothing to disclose. AL: Nothing to disclose. GB: Nothing to disclose. ZB: Nothing to disclose. NC: Nothing to disclose. AAS: Nothing to disclose. NMB: Consulting: Biomet (E), Bone Support (B), Daiichi Sankyo (E), Onkos (D).

Footnotes

FDA device/drug status: Not applicable.

References

- [1].Shaffer WO, Baisden JL, Fernand R, Matz PG. An evidence-based clinical guideline for antibiotic prophylaxis in spine surgery. Spine J 2013;13(10):1387–92. Epub 2013/08/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999;20(11):725–30. Epub 1999/12/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].de Lissovoy G, Fraeman K, Hutchins V, Murphy D, Song D, Vaughn BB. Surgical site infection: incidence and impact on hospital utilization and treatment costs. Am J infect Control 2009;37(5):387–97. Epub 2009/04/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Emohare O, Ledonio CG, Hill BW, Davis RA, Polly DW Jr, Kang MM . Cost savings analysis of intrawound vancomycin powder in posterior spinal surgery. Spine J 2014;14(11):2710–5. Epub 2014/03/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Godil SS, Parker SL, O’Neill KR, Devin CJ, McGirt MJ. Comparative effectiveness and cost-benefit analysis of local application of vancomycin powder in posterior spinal fusion for spine trauma: clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine 2013;19(3):331–5. Epub 2013/07/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zebala LP, Chuntarapas T, Kelly MP, Talcott M, Greco S, Riew KD. Intrawound vancomycin powder eradicates surgical wound contamination: an in vivo rabbit study. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol 2014;96 (1):46–51. Epub 2014/01/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Edelstein AI, Weiner JA, Cook RW, Chun DS, Monroe E, Mitchell SM, et al. Intra-articular vancomycin powder eliminates methicillin-resistant S. aureus in a rat model of a contaminated intra-articular implant. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol 2017;99(3):232–8. Epub 2017/02/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Khan NR, Thompson CJ, DeCuypere M, Angotti JM, Kalobwe E, Muhlbauer MS, et al. A meta-analysis of spinal surgical site infection and vancomycin powder. J Neurosurg Spine 2014;21(6):974–83. Epub 2014/09/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Martin JR, Adogwa O, Brown CR, Kuchibhatla M, Bagley CA, Lad SP, et al. Experience with intrawound vancomycin powder for posterior cervical fusion surgery. J Neurosurg Spine 2015;22(1):26–33. Epub 2014/11/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Molinari RW, Khera OA, Molinari WJ 3rd. Prophylactic intraoperative powdered vancomycin and postoperative deep spinal wound infection: 1,512 consecutive surgical cases over a 6-year period. Eur Spine J 2012;21(Suppl 4):S476–82. Epub 2011/12/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sweet FA, Roh M, Sliva C. Intrawound application of vancomycin for prophylaxis in instrumented thoracolumbar fusions: efficacy, drug levels, and patient outcomes. Spine 2011;36(24):2084–8. Epub 2011/02/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gans I, Dormans JP, Spiegel DA, Flynn JM, Sankar WN, Campbell RM, et al. Adjunctive vancomycin powder in pediatric spine surgery is safe. Spine 2013;38(19):1703–7. Epub 2013/06/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ghobrial GM, Cadotte DW, Williams K Jr, Fehlings MG, Harrop JS. Complications from the use of intrawound vancomycin in lumbar spinal surgery: a systematic review. Neurosurg Focus 2015;39(4):E11 Epub 2015/10/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].O’Neill KR, Smith JG, Abtahi AM, Archer KR, Spengler DM, McGirt MJ, et al. Reduced surgical site infections in patients undergoing posterior spinal stabilization of traumatic injuries using vancomycin powder. Spine J 2011;11(7):641–6. Epub 2011/05/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pahys JM, Pahys JR, Cho SK, Kang MM, Zebala LP, Hawasli AH, et al. Methods to decrease postoperative infections following posterior cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol 2013;95 (6):549–54. Epub 2013/03/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schroeder JE, Girardi FP, Sandhu H, Weinstein J, Cammisa FP, Sama A. The use of local vancomycin powder in degenerative spine surgery. Eur Spine J 2016;25(4):1029–33. Epub 2015/08/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Strom RG, Pacione D, Kalhorn SP, Frempong-Boadu AK. Decreased risk of wound infection after posterior cervical fusion with routine local application of vancomycin powder. Spine 2013;38(12):991–4. Epub 2013/01/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tubaki VR, Rajasekaran S, Shetty AP. Effects of using intravenous antibiotic only versus local intrawound vancomycin antibiotic powder application in addition to intravenous antibiotics on postoperative infection in spine surgery in 907 patients. Spine 2013;38(25):2149–55. Epub 2013/09/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Xiong L, Pan Q, Jin G, Xu Y, Hirche C. Topical intrawound application of vancomycin powder in addition to intravenous administration of antibiotics: a meta-analysis on the deep infection after spinal surgeries. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2014;100(7):785–9. Epub 2014/10/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hu Y, Hegde V, Johansen D, Loftin AH, Dworsky E, Zoller SD, et al. Combinatory antibiotic therapy increases rate of bacterial kill but not final outcome in a novel mouse model of Staphylococcus aureus spinal implant infection. PloS One 2017;12(2):e0173019 Epub 2017/03/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dworsky EM, Hegde V, Loftin AH, Richman S, Hu Y, Lord E, et al. Novel in vivo mouse model of implant related spine infection. J Orthop Res 2017;35(1):193–9. Epub 2016/04/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nair AB, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm 2016;7(2):27–31. Epub 2016/04/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pribaz JR, Bernthal NM, Billi F, Cho JS, Ramos RI, Guo Y, et al. Mouse model of chronic post-arthroplasty infection: noninvasive in vivo bioluminescence imaging to monitor bacterial burden for long-term study. J Orthop Res 2012;30(3):335–40. Epub 2011/08/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Martin JR, Adogwa O, Brown CR, Bagley CA, Richardson WJ, Lad SP, et al. Experience with intrawound vancomycin powder for spinal deformity surgery. Spine 2014;39(2):177–84. Epub 2013/10/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sutton S Accuracy of plate counts. J Valid Technol 2011;17(3):42. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Forrence EA, Goldman MP. Vancomycin-associated exfoliative dermatitis. DICP 1990;24(4):369–71. Epub 1990/04/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gutfeld MB, Reddy PV, Morse GD. Vancomycin-associated exfoliative dermatitis during continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Drug Intell ClinPharm 1988;22(11):881–2. Epub 1988/11/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Agarwal A, Kelkar A, Agarwal AG, Jayaswal D, Schultz C, Jayaswal A, et al. Implant retention or removal for management of surgical site infection after spinal surgery. Glob Spine J 2019. 2192568219869330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Prinz V, Bayerl S, Renz N, Trampuz A, Czabanka M, Woitzik J, et al. High frequency of low-virulent microorganisms detected by sonication of pedicle screws: a potential cause for implant failure. J Neurosurg Spine 2019;1(aop):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Agarwal A, Lin B, Elgafy H, Goel V, Karas C, Schultz C, et al. Updates on evidence-based practices to reduce preoperative and intraoperative contamination of implants in spine surgery: a narrative review. Spine Surg Relat Res 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]