Abstract

Colorectal cancer in the young adult population is of increasing incidence and concern. Genetic predisposition and heritable syndromes contribute to this trend, but perhaps more concerning is the majority of new diagnoses that involve no traceable genetic risk factors. Prevention and early recognition, with a high suspicion in the symptomatic young adult, are critical in attenuating recent trends. Clinical management requires coordinated multidisciplinary care from diagnosis to surveillance in order to ensure appropriate management. This review provides a summary of key aspects related to colorectal cancer in adolescents and young adults, including epidemiology, biology, genetics, clinical management, and prevention.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF COLORECTAL CANCER IN ADOLESCENTS AND YOUNG ADULTS

Incidence

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common and second most lethal malignancy worldwide according to the 2018 Global Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Prevalence database.1 In the United States, CRC incidence and mortality has been decreasing among individuals older than age 55 years, and this has been largely attributed to population-based CRC screening recommendations in place since the 1980s.2,3

However, the incidence of CRC among the adolescent and young adult (AYA) population (particularly those age 18-40 years) has shown an alarmingly opposite trend. In this population, CRC is being increasingly diagnosed, according to independent analyses from the following two major cancer databases in the United States: the SEER Program2,4-7 and the National Cancer Database (NCDB).8,9 For colon cancer, the adjusted incidence rates increased annually over roughly the past four decades by 2.4% in those age 20 to 29 years, by 1.0% in those age 30 to 39 years, and by 1.3% in those age 40 to 49 years; for rectal cancer, the adjusted incidence rates have increased by 3.2% in those age 20-39 years and by 2.3% in those age 40-49 years.2 Among patients ≤ 54 years of age, the percent change in incidence of rectal cancer has nearly quadrupled over the past few decades compared with colon cancer (41.5% [95% CI, 37.4% to 45.8%] v 9.8% [95% CI, 6.2% to 13.6%], respectively).7

Given the projection of current incidence rates to the year 2030, the largest predicted increase in colon (90%) and rectal (124%) cancer incidence will occur in the 20- to 34-year age group, whereas the incidence rates for colon and rectal cancer will decrease by 41% and 41.1%, respectively, for those older than age 50 years.5

In the United States, features of patients with CRC belonging to the AYA age group vary by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors. Based on the SEER database, CRC in patients younger than age 50 represents 6.7% of all CRCs in non-Hispanic whites, but the proportion varies in other races and ethnicities, with rates of 11.9% in African Americans, 12% in Asians/Pacific Islanders, 15.4% in Hispanics, and 16.5% in American Indians/Alaska Natives (P < .001).10 Importantly, data suggest that CRCs are diagnosed at more advanced stages in the AYA proportion of minority groups when compared with non-Hispanic whites.10 The highest mortality rates were seen in non-Hispanic black males (25.9%), American Indian/Alaska Native males (19.5%), and non-Hispanic white males (17.3%), whereas the lowest rates were observed in Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander males.11 Analysis of the NCDB showed that African American race and Hispanic ethnicity, lower household income, and lower education were among the independent negative predictors of overall survival (OS) for CRC in the AYA population when compared with the cohort of individuals ≥ 60 years of age.8

Unique Clinicopathologic Features

Overall, CRC occurring in the AYA population, henceforth termed young-onset CRC, shows a predilection for the distal colon and rectum. This has been consistently demonstrated in both SEER and NCDB.11,12 Young-onset CRC more often tends to involve regional nodes or distant sites at the time of diagnosis when compared with CRC in older patients (stage III or IV at diagnosis: 63% in young-onset CRC v 49% in older patients for colon cancer; and 57% in young-onset CRC v 46% in older patients for rectal cancer).13 Larger tumor size (> 5 cm), higher rates of perineural or lymphovascular invasion, and signet cell or mucinous histology have also been suggested to distinguish young-onset CRC.8,12

These differences in clinicopathologic features contribute to the complexity of survival analyses for young-onset CRC. A recent SEER analysis demonstrated an increase of 13% in the CRC mortality rate among patients age 20 to 49 years between 2000 and 2014, during which time the mortality rate among adults age 50 years or older declined by 34%.11 However, direct meaningful comparisons of survival outcomes between patients with young-onset CRC and individuals with later-onset disease are somewhat difficult, particularly because of significant confounding differences in demographics, socioeconomic factors, disease stage, stage-dependent treatments, tumor biology, and age-specific population-based expected survival rates.

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS FOR CRC IN THE AYA POPULATION

The etiology and risk factors for young-onset CRC constitute areas of active and ongoing investigation. Among the critical issues include the determination of whether young-onset CRC is of distinct etiology, the identification of risk factors that may enable targeted interventions, and the examination of drivers that may be responsible for the temporal increases in incidence rates. In the absence of classic hereditary conditions, it is postulated that an interplay between genetic alterations conferring elevated susceptibility and environmental conditions likely plays a significant role in the development of young-onset CRC.

Germline Genetic Predisposition

Pathogenic germline mutations associated with major hereditary cancer syndromes account for a distinct subset of patients with young-onset CRC.14,15 Although this proportion is approximately 2% to 5% of all patients with CRC, it increases to approximately 16% to 20% when considering patients with CRC between the ages of 18 and 50 years and can be as high as 35% among patients with CRC between ages 18 and 35 years.15-18

Lynch syndrome is the most common hereditary CRC syndrome, arising from germline mutations that cause deficiencies in the native DNA mismatch repair mechanisms.15,19,20 A cost-effective method of universal screening for Lynch syndrome is testing the CRC tumor specimen for evidence of microsatellite instability and/or immunohistochemical evaluation for the expression of the key mismatch repair proteins. The rate of microsatellite instability ranges from 12% to 17% in the general population19 but may be as high as 27% to 35% in patients younger than age 30 years.15,21 Subsequent confirmatory germline testing typically identifies pathogenic mutations in one of the four major mismatch repair genes, most commonly in MLH1 or MSH2 (60%-80%) and less commonly in MSH6, PMS2 (10%-20%), or EPCAM (3%).20,22 The lifetime risk for CRC ranges from 40% to 70% for patients with Lynch syndrome, significantly exceeding that of the general population.23 The Lynch syndrome–related CRCs tend to occur at younger ages, with a median age at diagnosis of approximately 40 years, and they more commonly arise in the right colon.23

Hereditary CRC syndromes that share a polyposis phenotype include classic and attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis, MUTYH-associated polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, juvenile polyposis syndrome, polymerase proofreading–associated polyposis, and NTHL1-associated polyposis. Familial adenomatous polyposis is driven by a germline mutation in the APC gene that clinically translates into the formation of numerous intestinal adenomas. Although the consequent risk of CRC is influenced by the degree of polyposis and adequacy of endoscopic surveillance, the rate of malignant transformation can approach 100% by the fifth decade of life in some patients.24 MUTYH-associated polyposis and NTHL1-associated polyposis are derived from germline mutations in the MYH and the NTHL1 genes, respectively.25,26 Both encode for DNA glycosylases that are involved in the base excision repair mechanism and are inherited in autosomal recessive fashion.25,26 Biallelic MYH mutations confer a 28-fold higher risk for CRC compared with the general population.25,26 Patients with polymerase proofreading–associated polyposis carry rare germline mutations in the POLE and POLD1 genes, which encode for proofreading regions of DNA polymerases that lead to the development of multiple colorectal adenomas and young-onset CRC.27 Germline mutations in the tumor suppressor genes STK11 and LKB1 cause Peutz-Jeghers syndrome,28 whereas those in SMAD4/BMPR1A lead to juvenile polyposis syndrome.29 Polyps associated with the latter syndromes are characterized by hamartomatous rather than adenomatous histology.

Other subsets of patients who develop young-onset CRC may harbor elevated genetic risk without a well-defined pathogenic germline mutation. Some patients present with clinical suspicion for Lynch syndrome and CRC with microsatellite instability yet lack pathogenic germline mutations in a mismatch repair gene.30-32 These individuals are defined as having mutation-negative Lynch syndrome or Lynch-like syndrome.30-33 Their adjusted standardized incidence ratio (SIR) for CRC is 2.12 (95% CI, 1.16 to 3.56), which is lower than that conferred by Lynch syndrome but higher than the population risk.33 Other patients whose family history meets the Amsterdam criteria and who have mismatch repair–proficient CRCs have been diagnosed as having familial CRC syndrome X.34,35 Their risk for CRC is increased two-fold (SIR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.7 to 3.0) but is lower than that in patients with Lynch syndrome (SIR, 6.1; 95% CI, 5.2-7.2; P < .001).36,37 Finally, a family history of CRC in at least one first-degree relative is associated with a 2.24-fold (range, 1.55-2.80) increased risk for CRC.38

Somatic Genetic Mutations

Three major pathways of CRC carcinogenesis have been described: chromosomal instability, microsatellite instability, and CpG island methylator phenotype.39 Approximately 70% of sporadic CRCs arise via chromosomal instability,40 which is hallmarked by somatic mutations in the APC tumor suppressor gene, an early driver mutation in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence.41,42 These tumors are microsatellite stable, lack CpG island methylator phenotype,43 and harbor deactivating mutations in the tumor suppressor genes APC and TP53 and activating mutations in the proto-oncogenes KRAS and MYC.44,45 Young-onset CRCs exhibiting chromosomal instability arise primarily in the proximal colon, in contrast to later-onset chromosomal instability–associated CRCs, which tend to be located in the distal colon.44,45 Although microsatellite instability is the key feature of Lynch syndrome, a specific subset of young-onset CRC is characterized as microsatellite-stable and chromosome-stable CRCs and have an anatomic predilection for the distal colon and rectum.46,47 Microsatellite-stable and chromosome-stable tumors are biologically aggressive, with tendencies toward early metastasis and recurrence.46-49 They are further characterized by LINE-1 hypomethylation, CpG island methylator phenotype low status, and an absence of BRAF mutations.50-52 Another subset of young-onset CRC is associated with CpG island methylator phenotype low status and presents with a positive family history and a predominance of left-sided tumors.48,53

Environmental and Lifestyle Contributors

Although environmental and lifestyle habits such as red meat consumption and sedentary lifestyle are established risk factors for CRC in general,54-56 their specific contributions to young-onset CRC have yet to be established. The following worrisome trends have been observed: the consumption of fast food has increased three- to five-fold among children and young adults57; obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome have increasingly affected younger adults58; and smoking has been shown to lower the age of CRC onset.59 A recent analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study showed that obesity or a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30 kg/m2 was independently associated with a nearly two-fold greater risk for young-onset CRC, as were higher BMI at age 18 years and weight gain of > 20 kg during adulthood.60

An environment of chronic tissue inflammation has been associated with malignant transformation. A subset of young-onset CRC arises in association with underlying inflammatory bowel disease. Indeed, Crohn colitis and ulcerative colitis confer a CRC risk of 2% after 10 years, 8% after 20 years, and 18% after 30 years of disease, with a greater risk in the setting of those with pancolitis.61

The role of the colon microbiome in colon carcinogenesis is a novel area of active investigation. Pathobiotic bacteria can promote CRC through chronic inflammation with accumulation of DNA damage in epithelial cells.62 Emerging evidence suggests that Fusobacterium nucleatum may be enriched in right-sided CRCs.63,64 It is capable of upregulating the expression of oncogenic and proinflammatory genes,65 and its detection in tumor tissue has been prognostic of OS.66 However, whether a unique microbiome milieu is associated with young-onset CRC remains unknown.

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF CRC IN THE AYA POPULATION

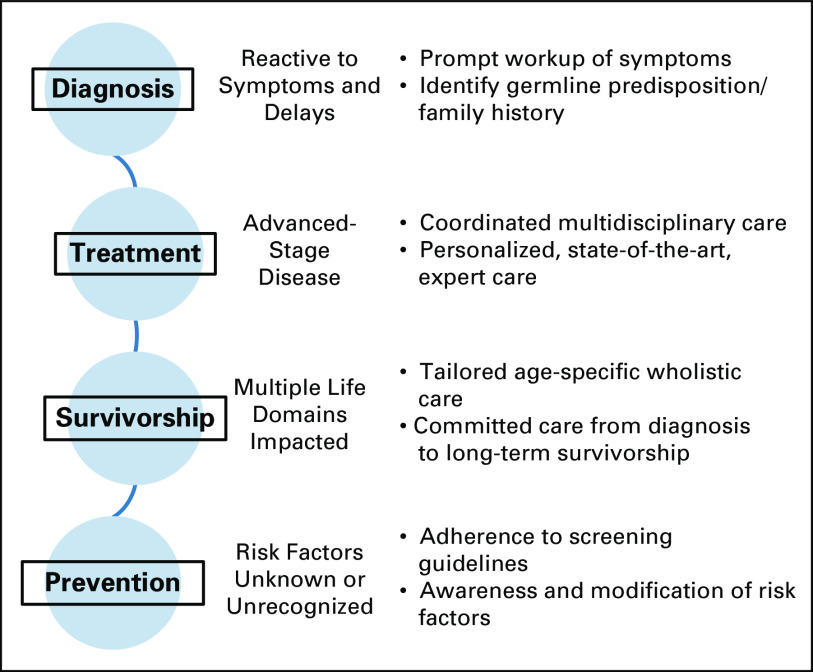

The management of young-onset CRC can be comparatively demanding because of the frequent advanced stage at diagnosis, the requirement for coordinated multimodality treatments, and the need to treat the whole patient for whom multiple life domains are significantly impacted by the cancer diagnosis (often even more so than the individual with later-onset CRC). Care should also be provided throughout the cancer spectrum, ranging from diagnosis and treatment to surveillance, survivorship, and prevention (Fig 1). Thus, early referral to centers with multidisciplinary support should be considered.

Fig 1.

Challenges and associated opportunities for improvement throughout the spectrum of care for young adult patients with colorectal cancer.

Diagnosis

Avoiding delay in diagnosis of young-onset CRC is an urgent challenge for all health care providers. Given the limited role of CRC screening (discussed in the Prevention and Early Detection section below) among asymptomatic young adults, the majority of young-onset CRCs (86%) are diagnosed after symptomatic presentation.67,68 The predilection for distal colon and rectum translates to symptoms such as rectal bleeding, rectal pain, altered bowel habits, bloating, abdominal pain, and nausea and vomiting.67,69 Young adults tend to wait longer than older adults between symptom onset and presentation (up to 6.2 months) and also experience further delays until treatment initiation compared with older adults (217 v 29.5 days, respectively; P < .001).6,69-72 Attribution of symptoms to benign anorectal pathology such as hemorrhoids without additional workup is unfortunately common.67,72 Given factors such as underinsurance and hesitancy to seek care among the AYA population, a high degree of suspicion and expeditious diagnostic workup of the symptomatic AYA patient are crucial to help decrease the disproportionate late-stage presentations of young-onset CRC.2,4,9,32,69,72,73

A histologic diagnosis of CRC should be expeditiously obtained, typically through endoscopic biopsy. A full colonoscopy efficiently assesses the entire colon but may not be possible in cases of obstructing distal tumors. Additional clinical assessment should include comprehensive oncologic staging and investigation of heritable predisposing conditions. Physical examination, including digital rectal examination; laboratory studies, including CBC, chemistry panel, and carcinoembryonic antigen level; and staging computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis for colon cancer, with use of high-resolution pelvic magnetic resonance imaging for local evaluation of rectal cancer, constitute standard components of clinical staging.74,75 Potential underlying hereditary CRC syndromes should be considered in every AYA patient. Examination for extracolonic manifestations and documentation of family cancer history should be routine.18,76 Referral for genetic counseling, risk assessment, and germline testing of either targeted genes or a multiplex panel should be initiated as appropriate.77,78

Oncologic Management

Because the majority of patients with young-onset CRC present with locally advanced or metastatic disease, coordinated multidisciplinary expert care is essential.9 Special attention should be paid to personalization of surgical decision making, initiation of appropriate complex multimodality treatments (with avoidance of overtreatment), consideration of age-specific issues regarding long-term toxicities, and identification of somatic and/or germline tumor genetics that may impact treatment choices.

Surgical resection of nonhereditary young-onset CRC should adhere to standard oncologic principles appropriate for the respective tumor site.74,75 Advanced minimally invasive oncologic surgical expertise may be particularly beneficial, because shorter length of stay, earlier return to work, and improved cosmesis are of greater relevance in the AYA population.79-81 The overall higher level of baseline bowel function and continence may allow for more aggressive sphincter-preserving techniques such as coloanal anastomosis and/or intersphincteric dissection in some patients.13,82 Caution should be taken not to overtreat the AYA population, despite the lower morbidity risk and higher life-years left to gain. For patients with sporadic young-onset CRC, extended resections such as total colectomy or proctocolectomy have not demonstrated any advantage in disease-free survival (DFS) or OS.83,84 The surgical management of patients with young-onset CRC who harbor underlying Lynch syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis requires considerations for both the index CRC and the remaining colorectum at risk. The choice of surgery for hereditary cancer syndromes has been reviewed extensively elsewhere.85-87 Extended resections should be considered in the context of alteration of bowel function and life expectancy based on age and index CRC.

In the absence of distinct biologic features, current treatment guidelines do not distinguish young-onset CRC from later-onset disease.74 In practice, however, AYA patients are at risk for receiving more aggressive treatments that do not necessarily translate into significant survival advantages.88-90 After curative-intent surgical resection, adjuvant therapy is indicated for high-risk stage II and III disease.74,75 In the pooled analysis of the Adjuvant Colon Cancer Endpoints database, patients younger than 40 years old with stage II or III colon cancers had DFS and OS comparable to those of their older counterparts.91 Compared with older counterparts, AYA patients are more likely to receive oxaliplatin-based multidrug chemotherapy regimens, such as capecitabine and oxaliplatin (CAPOX) or fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin.88,90,92 Moreover, some AYA patients with stage I or low-risk stage II colon cancer have received unindicated adjuvant regimens, highlighting the risk for overtreatment faced by this population.88,90 Recently, the International Duration Evaluation of Adjuvant Therapy collaboration demonstrated noninferiority in DFS of a 3-month versus 6-month regimen of adjuvant CAPOX in patients with low-risk stage III colon cancer.93 Reduced duration of therapy may be of special significance in the AYA population given the marked reduction in neurotoxicity risk and potential diminished negative impact on quality of life.93

For both stage IV young-onset CRC and later-onset CRC, standard first-line therapy typically includes an oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based multiagent regimen combined with a biologic agent.74 Population-based analyses of the SEER database have demonstrated a 7% to 12% advantage in 5-year disease-specific survival for stage IV AYA patients compared with older patients.4,94 AYA patients with distant metastasis, compared with older patients, are more likely to undergo surgical resection (72% v 63%, respectively; P < .001) and radiation (53% v 48%, respectively; P < .001) for their primary tumor.4,94 Given the higher proportion of advanced-stage disease in young-onset CRC coupled with the tendency for overtreatment, multidisciplinary coordination of care is imperative to define appropriate, individualized treatment plans.

Special attention should be paid to the potential for molecularly tailored therapy in the AYA population. In association with Lynch syndrome, a higher proportion of young-onset CRCs may have microsatellite instability and require specific considerations.95,96 Patients with CRC with microsatellite instability have a better overall prognosis compared with patients with microsatellite-stable CRC, and in the setting of stage II CRC with microsatellite instability, there is generally no benefit (and potentially harm) of adjuvant therapy with single-agent fluorouracil-based regimens.74,97 However, patients with stage III colon cancer with microsatellite instability should receive standard oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy.74 Patients with locally advanced rectal cancer with microsatellite instability should also be treated in standard fashion with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy because approximately 27% of these patients may achieve pathologic complete response.98 Finally, ongoing clinical trials in the metastatic stage IV setting have demonstrated dramatic response of tumors with microsatellite instability to immunotherapy (antibodies against PD1, PDL1, and CTLA4).74,99-101

The somatic mutation profiling of sporadic young-onset CRC has demonstrated similar mutation rates for common genes mutated in CRCs. Notable exceptions have included a relatively lower incidence of BRAF mutations and increased frequency of the F-box and WD repeating-containing 7 (FBXW7) and polymerase ∈ catalytic subunit (POLE) mutations.102 BRAF mutations indicate a poorer prognosis and have associated treatment implications.12 Additionally, decreased function of the FBXW7 protein has been associated with poor survival.103 Mutations in POLE confer a hypermutated phenotype and may have treatment implications with immunotherapy, as in the case of CRCs with microsatellite instability.102

Cancer Survivorship Management

The CRC experience is unique for AYA patients because it significantly impacts multiple domains of their young adulthood.104 Comprehensive survivorship care is needed starting at the time of diagnosis and extending through surveillance and long-term follow-up. Psychosocial support and networking through AYA patient communities play important roles, because AYA patients may have limited life experiences and underdeveloped coping skills.104 Long-term survivors of young-onset CRC persistently experienced worse anxiety, body image, and embarrassment with bowel movements when compared with their older counterparts.104 Survivors of CRC who had been diagnosed before age 60 years also reported restrictions in role, social, emotional, and cognitive functioning as well as specific symptoms of constipation, diarrhea, fatigue, and insomnia.105 Finally, oncofertility and family planning, financial and employment counseling, and nutrition and integrative medicine may be of particular interest to AYA patients and could be offered proactively. The overall cancer surveillance and survivorship care guidelines for CRC should still be followed for patients with young-onset CRC.74,75

Prevention and Early Detection

Risk factor modification and screening have been credited as the largest contributors to the overall decline in CRC mortality.3 Because risk factors specific to young-onset CRC remain to be elucidated, current prevention recommendations for young-onset CRC have not significantly differed from those for later-onset disease. Historically, average-risk screening for CRC has been recommended to commence at age 50 years.106-109 However, in 2018, the American Cancer Society issued an additional qualified recommendation to begin average-risk screening at age 45 years.108 Microsimulation models developed by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network simulated life-years gained from screening relative to the burden of colonoscopies with their costs and potential complications.110 Retrospective data from colonoscopies performed in individuals age 40 to 49 years have shown similar rates in adenoma detection when compared with older adults, but the low rate of advanced neoplasia fails to provide compelling evidence to initiate routine screening in this younger age group.111,112 However, updated modeling adjusting for the increasing young-onset CRC incidence indicated that initiating colonoscopic screening at age 45 (v age 50) increased life-years gained by 6.2% at the cost of 17% more colonoscopies per 1,000 adults over an individual’s lifetime of screening.108,113 The American Cancer Society recommendation also allows for multiple screening methods, including fecal studies. Lowering the screening age to 45 years aims to ameliorate the increasing burden of young-onset CRC.

CRC screening should occur before age 50 years for individuals at elevated risk for CRC. First, specific guidelines for earlier initiation of screening exist for patients with major hereditary CRC syndromes and inflammatory bowel disease.114 Second, relevant personal or family history warrants earlier screening. Individuals with a family history of advanced adenoma or CRC in one first-degree relative before age 60 years or two first-degree relatives at any age should initiate screening colonoscopy 10 years before the age of diagnosis of the youngest affected relative or at age 40 years (whichever comes first).106,108 Third, initiating screening at an earlier age for African Americans has been recommended.115 Although these classic high-risk screening indications of hereditary syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and family history are more likely to be present in patients with young-onset CRC,69 they likely account for only up to 30% of the young-onset CRCs.68 Nonetheless, improved capture of family cancer history and real-life adherence to risk-based screening guidelines are areas that need major improvement.73

In conclusion, the AYA population is being increasingly afflicted by CRC and its threat to both life expectancy and quality of life. The clinical management of these patients must include expertise in clinical genetics for the potential presence of a hereditary predisposition syndrome, advanced multidisciplinary treatment coordination, and comprehensive attention to the multiple life domains damaged by the cancer diagnosis as well as long-term survivorship. The increasing incidence and advanced stage at diagnosis of young-onset CRC indicate an urgent need for increased awareness of this disease, so that symptomatic AYA patients can be expeditiously diagnosed. The recent recommendation for CRC screening of asymptomatic adults starting at age 45 years reflects a desire to help reverse the morbidity of CRC in the AYA population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported in part by University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Core Support Grant No. P30 CA016672.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Y. Nancy You, Benjamin W. Deschner, David Shibata

Collection and assembly of data: Y. Nancy You, Lucas D. Lee

Data analysis and interpretation: Y. Nancy You

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Colorectal Cancer in the Adolescent and Young Adult Population

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djw322. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116:544–573. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdelsattar ZM, Wong SL, Regenbogen SE, et al. Colorectal cancer outcomes and treatment patterns in patients too young for average-risk screening. Cancer. 2016;122:929–934. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:17–22. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increase in incidence of colorectal cancer among young men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1695–1698. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs D, Zhu R, Luo J, et al. Defining early-onset colon and rectal cancers. Front Oncol. 2018;8:504. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabriel E, Attwood K, Al-Sukhni E, et al. Age-related rates of colorectal cancer and the factors associated with overall survival. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9:96–110. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2017.11.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.You YN, Xing Y, Feig BW, et al. Young-onset colorectal cancer: Is it time to pay attention? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:287–289. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman R, Schmaltz C, Jackson CS, et al. Increased risk for colorectal cancer under age 50 in racial and ethnic minorities living in the United States. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1863–1870. doi: 10.1002/cam4.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:177–193. doi: 10.3322/caac.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeo H, Betel D, Abelson JS, et al. Early-onset colorectal cancer is distinct from traditional colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16:293–299.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.You YN, Dozois EJ, Boardman LA, et al. Young-onset rectal cancer: Presentation, pattern of care and long-term oncologic outcomes compared to a matched older-onset cohort. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2469–2476. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1674-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jasperson KW, Tuohy TM, Neklason DW, et al. Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2044–2058. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mork ME, You YN, Ying J, et al. High prevalence of hereditary cancer syndromes in adolescents and young adults with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3544–3549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearlman R, de la Chapelle A, Hampel H. Mutation frequencies in patients with early-onset colorectal cancer-reply. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1587. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoffel EM, Koeppe E, Everett J, et al. Germline genetic features of young individuals with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:897–905.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dineen S, Lynch PM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, et al. A prospective six sigma quality improvement trial to optimize universal screening for genetic syndrome among patients with young-onset colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:865–872. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boland CR, Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2073–2087.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinicrope FA. Lynch syndrome-associated colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:764–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1714533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim NH, Jung YS, Yang HJ, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic young adults (20-39 years old) Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch HT, Lanspa S, Shaw T, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity of Lynch syndrome: A complex diagnostic challenge. Fam Cancer. 2018;17:403–414. doi: 10.1007/s10689-017-0053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoffel E, Mukherjee B, Raymond VM, et al. Calculation of risk of colorectal and endometrial cancer among patients with Lynch syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1621–1627. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Sukhni W, Aronson M, Gallinger S. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: Familial adenomatous polyposis and lynch syndrome. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:819–844. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weren RD, Ligtenberg MJ, Geurts van Kessel A, et al. NTHL1 and MUTYH polyposis syndromes: Two sides of the same coin? J Pathol. 2018;244:135–142. doi: 10.1002/path.5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weren RD, Ligtenberg MJ, Kets CM, et al. A germline homozygous mutation in the base-excision repair gene NTHL1 causes adenomatous polyposis and colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47:668–671. doi: 10.1038/ng.3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palles C, Cazier JB, Howarth KM, et al. Germline mutations affecting the proofreading domains of POLE and POLD1 predispose to colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45:136–144. doi: 10.1038/ng.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campos FG, Figueiredo MN, Martinez CA. Colorectal cancer risk in hamartomatous polyposis syndromes. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7:25–32. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i3.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zbuk KM, Eng C. Cancer phenomics: RET and PTEN as illustrative models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:35–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dempsey KM, Broaddus R, You YN, et al. Is it all Lynch syndrome? An assessment of family history in individuals with mismatch repair-deficient tumors. Genet Med. 2015;17:476–484. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.You YN, Vilar E. Classifying MMR variants: Time for revised nomenclature in Lynch syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2280–2282. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee LD, You YN. Young-onset colorectal cancer: Diagnosis and management. Semin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;29:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez-Soler M, Perez-Carbonell L, Guarinos C, et al. Risk of cancer in cases of suspected Lynch syndrome without germline mutation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:926–932.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dominguez-Valentin M, Therkildsen C, Da Silva S, et al. Familial colorectal cancer type X: Genetic profiles and phenotypic features. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:30–36. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zetner DB, Bisgaard ML. Familial colorectal cancer type X. Curr Genomics. 2017;18:341–359. doi: 10.2174/1389202918666170307161643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindor NM. Familial colorectal cancer type X: The other half of hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2009;18:637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindor NM, Rabe K, Petersen GM, et al. Lower cancer incidence in Amsterdam-I criteria families without mismatch repair deficiency: Familial colorectal cancer type X. JAMA. 2005;293:1979–1985. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowery JT, Ahnen DJ, Schroy PC, III, et al. Understanding the contribution of family history to colorectal cancer risk and its clinical implications: A state-of-the-science review. Cancer. 2016;122:2633–2645. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cavestro GM, Mannucci A, Zuppardo RA, et al. Early onset sporadic colorectal cancer: Worrisome trends and oncogenic features. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goel A, Nagasaka T, Spiegel J, et al. Low frequency of Lynch syndrome among young patients with non-familial colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:966–971. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fodde R. The APC gene in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:867–871. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Powell SM, Zilz N, Beazer-Barclay Y, et al. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature. 1992;359:235–237. doi: 10.1038/359235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang DT, Pai RK, Rybicki LA, et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular features of sporadic early-onset colorectal adenocarcinoma: An adenocarcinoma with frequent signet ring cell differentiation, rectal and sigmoid involvement, and adverse morphologic features. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1128–1139. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Connell LC, Mota JM, Braghiroli MI, et al. The rising incidence of younger patients with colorectal cancer: Questions about screening, biology, and treatment. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:23. doi: 10.1007/s11864-017-0463-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farooqi AA, de la Roche M, Djamgoz MBA, et al. Overview of the oncogenic signaling pathways in colorectal cancer: Mechanistic insights. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;58:65–79. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banerjea A, Hands RE, Powar MP, et al. Microsatellite and chromosomal stable colorectal cancers demonstrate poor immunogenicity and early disease recurrence. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:601–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sinicrope FA, Rego RL, Halling KC, et al. Prognostic impact of microsatellite instability and DNA ploidy in human colon carcinoma patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:729–737. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chan TL, Curtis LC, Leung SY, et al. Early-onset colorectal cancer with stable microsatellite DNA and near-diploid chromosomes. Oncogene. 2001;20:4871–4876. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hawkins NJ, Tomlinson I, Meagher A, et al. Microsatellite-stable diploid carcinoma: A biologically distinct and aggressive subset of sporadic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:232–236. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antelo M, Balaguer F, Shia J, et al. A high degree of LINE-1 hypomethylation is a unique feature of early-onset colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cai G, Xu Y, Lu H, et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular features of sporadic microsatellite- and chromosomal-stable colorectal cancers. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:365–373. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silver A, Sengupta N, Propper D, et al. A distinct DNA methylation profile associated with microsatellite and chromosomal stable sporadic colorectal cancers. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1082–1092. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perea J, Rueda D, Canal A, et al. Age at onset should be a major criterion for subclassification of colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolin KY, Yan Y, Colditz GA, et al. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: A meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:611–616. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larsson SC, Rutegård J, Bergkvist L, et al. Physical activity, obesity, and risk of colon and rectal cancer in a cohort of Swedish men. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2590–2597. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larsson SC, Wolk A. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2657–2664. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guthrie JF, Lin BH, Frazao E. Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977-78 versus 1994-96: Changes and consequences. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34:140–150. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Larsson SC, Wolk A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:556–565. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peppone LJ, Mahoney MC, Cummings KM, et al. Colorectal cancer occurs earlier in those exposed to tobacco smoke: Implications for screening. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:743–751. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0332-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu PH, Wu K, Ng K, et al. Association of obesity with risk of early-onset colorectal cancer among women. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:37–44. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keller DS, Windsor A, Cohen R, et al. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: Review of the evidence. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s10151-019-1926-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen J, Pitmon E, Wang K. Microbiome, inflammation and colorectal cancer. Semin Immunol. 2017;32:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dejea CM, Wick EC, Hechenbleikner EM, et al. Microbiota organization is a distinct feature of proximal colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:18321–18326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406199111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mima K, Cao Y, Chan AT, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue according to tumor location. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e200. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubinstein MR, Wang X, Liu W, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mima K, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut. 2016;65:1973–1980. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dozois EJ, Boardman LA, Suwanthanma W, et al. Young-onset colorectal cancer in patients with no known genetic predisposition: Can we increase early recognition and improve outcome? Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:259–263. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181881354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen FW, Sundaram V, Chew TA, et al. Low prevalence of criteria for early screening in young-onset colorectal cancer. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:933–934. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen FW, Sundaram V, Chew TA, et al. Advanced-stage colorectal cancer in persons younger than 50 years not associated with longer duration of symptoms or time to diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:728–737.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scott RB, Rangel LE, Osler TM, et al. Rectal cancer in patients under the age of 50 years: The delayed diagnosis. Am J Surg. 2016;211:1014–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Inra JA, Syngal S. Colorectal cancer in young adults. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:722–733. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Livingston EH, et al. Colorectal cancer in the young. Am J Surg. 2004;187:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2018: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:297–316. doi: 10.3322/caac.21446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Benson AB, III, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: Colon cancer, version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:359–369. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Benson AB, III, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. Rectal cancer, version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:874–901. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stoffel EM, Boland CR. Genetics and genetic testing in hereditary colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1191–1203.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Robson ME, Bradbury AR, Arun B, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: Genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3660–3667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pearlman R, Frankel WL, Swanson B, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of germline cancer susceptibility gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:464–471. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abu Gazala M, Wexner SD. Re-appraisal and consideration of minimally invasive surgery in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017;5:1–10. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gox001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J, et al. Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1638–1645. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fleshman J, Branda ME, Sargent DJ, et al. Disease-free survival and local recurrence for laparoscopic resection compared with open resection of stage II to III rectal cancer: Follow-up results of the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2019;269:589–595. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martin ST, Heneghan HM, Winter DC. Systematic review of outcomes after intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:603–612. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kozak VN, Kalady MF, Gamaleldin MM, et al. Colorectal surveillance after segmental resection for young-onset colorectal cancer: Is there evidence for extended resection? Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:O386–O392. doi: 10.1111/codi.13874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klos CL, Montenegro G, Jamal N, et al. Segmental versus extended resection for sporadic colorectal cancer in young patients. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:328–332. doi: 10.1002/jso.23649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: A consensus statement by the US Multi-society Task Force on colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1159–1179. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Herzig D, Hardiman K, Weiser M, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the management of inherited polyposis syndromes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:881–894. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herzig DO, Buie WD, Weiser MR, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the surgical treatment of patients with Lynch syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:137–143. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kneuertz PJ, Chang GJ, Hu CY, et al. Overtreatment of young adults with colon cancer: More intense treatments with unmatched survival gains. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:402–409. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.3572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kolarich A, George TJ, Jr, Hughes SJ, et al. Rectal cancer patients younger than 50 years lack a survival benefit from NCCN guideline-directed treatment for stage II and III disease. Cancer. 2018;124:3510–3519. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Manjelievskaia J, Brown D, McGlynn KA, et al. Chemotherapy use and survival among young and middle-aged patients with colon cancer. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:452–459. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hubbard J, Thomas DM, Yothers G, et al. Benefits and adverse events in younger versus older patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: Findings from the Adjuvant Colon Cancer Endpoints data set. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2334–2339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Quah HM, Joseph R, Schrag D, et al. Young age influences treatment but not outcome of colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2759–2765. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grothey A, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1177–1188. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fu J, Yang J, Tan Y, et al. Young patients (≤ 35 years old) with colorectal cancer have worse outcomes due to more advanced disease: A 30-year retrospective review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e135. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hubbard JM, Grothey A. Adolescent and young adult colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1219–1225. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ET, et al. Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:69–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3219–3226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.de Rosa N, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Chang GJ, et al. DNA mismatch repair deficiency in rectal cancer: Benchmarking its impact on prognosis, neoadjuvant response prediction, and clinical cancer genetics. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3039–3046. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.6826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Link JT, Overman MJ. Immunotherapy progress in mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer and future therapeutic challenges. Cancer J. 2016;22:190–195. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Overman MJ, Ernstoff MS, Morse MA. Where we stand with immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: Deficient mismatch repair, proficient mismatch repair, and toxicity management. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:239–247. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_200821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KYM, et al. Durable clinical benefit with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:773–779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.9901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kothari N, Teer JK, Abbott AM, et al. Increased incidence of FBXW7 and POLE proofreading domain mutations in young adult colorectal cancers. Cancer. 2016;122:2828–2835. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Iwatsuki M, Mimori K, Ishii H, et al. Loss of FBXW7, a cell cycle regulating gene, in colorectal cancer: Clinical significance. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1828–1837. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bailey CE, Tran Cao HS, Hu CY, et al. Functional deficits and symptoms of long-term survivors of colorectal cancer treated by multimodality therapy differ by age at diagnosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:180–188. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2645-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jansen L, Herrmann A, Stegmaier C, et al. Health-related quality of life during the 10 years after diagnosis of colorectal cancer: A population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3263–3269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: Recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:307–323. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Hopkins RH, Jr, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: A guidance statement from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:378–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.21457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315:2564–2575. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: Modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:2595–2609. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rundle AG, Lebwohl B, Vogel R, et al. Colonoscopic screening in average-risk individuals ages 40 to 49 vs 50 to 59 years. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1311–1315. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, et al. Results of screening colonoscopy among persons 40 to 49 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1781–1785. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200206063462304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Peterse EFP, Meester RGS, Siegel RL, et al. The impact of the rising colorectal cancer incidence in young adults on the optimal age to start screening: Microsimulation analysis I to inform the American Cancer Society colorectal cancer screening guideline. Cancer. 2018;124:2964–2973. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gupta S, Provenzale D, Regenbogen SE, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Colorectal, version 3.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:1465–1475. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Meester RGS, Peterse EFP, Knudsen AB, et al. Optimizing colorectal cancer screening by race and sex: Microsimulation analysis II to inform the American Cancer Society colorectal cancer screening guideline. Cancer. 2018;124:2974–2985. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]