Abstract

Our current predicament, the Covid-19 pandemic is first of all a health crisis. However, social disruption and economic damage are becoming visible some 7 months after the Wuhan City outbreak early December 2019. The authors wondered what could have been done better in prevention and repression of the Covid-19 pandemic from a safety management and risk control point of view.

Within a case study framework, the authors gathered literature on pandemics, about country response effectiveness, and about human behaviour in the face of danger. The results consist of a safety management oriented narrative about the current pandemic, several critical observations about the current paradigms and shortcomings of preparation, and a number of opportunities for improvements of countermeasures. Many of the proverbial animals in the safety zoo, representing typical behaviours, were observed in action.

Based on well proven risk analysis methods – risk management, event tree, scenarios, bowtie – the authors then analyse the generic sequence of events in a pandemic, starting from root causes, through prevention, via the outbreak of a pathogen, through mitigation to long term effects. Based on this analysis the authors propose an integrated pandemics barrier model. In this model the core is a generic pandemic scenario that is distinguishing five risk controllable sequential steps before an outbreak.

The authors contend that the prevention of pandemics via safety management based biohazard risk control is both possible and of paramount importance since it can stop pandemic scenarios altogether even before an outbreak.

Keywords: Safety management, Pandemic, Scenario, Paradigm, Bowtie, Integrated pandemics barrier model, Safety zoo, Lessons learned

“The world has never faced this scale of challenge before. COVID-19 is a truly global crisis, and the only way to overcome it is together, in global solidarity.” [Quote: WHO Situation report-91, April 20, 2020]

1. Introduction

People, thinking about safety, use quite a few animals as representations of safety concepts. In addition to Paper tigers (Dekker,2014), Dinosaurs (Cohen, 2005), Black swans (Taleb, 2007), Dragons (Elahi, 2011) and Elephants (Srivatsa, 2018), Michelle Wucker (2016) introduced Gray rhino’s in – what by now could be called – the ‘safety zoo’.

Michele Wucker (2017) herself issued a Reader Discussion Guide to complement her 2016 book about the Gray Rhino (Wucker, 2016). In her 2017 ‘discussion questions’ yet more animals appear, all most welcome in the safety zoo.

Nathan Jaye (2017) interviews Michele Wucker on October 23, 2017 asking her about ‘black swans’. In safety science those stand for the combination of unlikely factors suddenly creating a big problem. Wucker explains that the ‘gray rhino’ is staring you in the face, ready to cause havoc. You’d better find out why you are not responding and use the opportunity to act while you still can. Then Jaye continues asking about the ‘elephant in the room’. Wucker replies with an explanation about how difficult it can be to even see a nearby group of very large elephants in their natural habitat. Jaye and Wucker then engage in a discussion about China and – among other things – about recurring influenza viruses, comparing them with recurring ‘gray rhino’s’. Not reacting to a charging rhino is the worst thing to do, even when you are frightened, prone to freezing on the spot or are scared to make a wrong choice. Later, Schleicher (2020, p.4) writes that the ‘gray rhino’ is “a perfect complement to the Black Swan concept”. It is about “engaging more thoroughly with reality, recognizing obvious threats and our own biases, and working to overcome them”.

These animal-concepts all address safety problems we do not seem to handle very well. We deem these problems as unknown, ignore them, accept their risk, regard them as unlikely and we just don’t act on them, even when we really should and actually could.

And yes, an Ostrich bird springs to mind …

Some of us feel that mankind - living in the Anthropocene era (Crutzen, 2004) as a result of natural selection - is now in command of the planet. But how vulnerable are we, between a hot and violent earth beneath us and cold outer space surrounding us from above? How bad could things actually get?

Wucker (2017) speculates about “planetary [scale] gray rhino’s”, referring to some of the catastrophic dangers we can do little about. One would be a magnetic storm coming from the Sun, wiping out the electrical part of our society, similar to the Carrington Event in 1859 (Cliver, 2006). Another one which manifested itself before, is the extinction of dinosaurs after the successive Yucatan and Shiva asteroid impacts 65 million years ago (Lerbekmo, 2014). The prevention of such disasters is currently beyond our capabilities. Nature may throw earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, enormous firestorms and tsunamis at us in the wake of such impact. Mitigation would for the most part also be beyond our possibilities. However, as we are continuously watching every earth approaching rock we can see, and are experimenting with ways to change their direction in case they pose a threat, we are not at our wit’s end when it comes to future development of preventive means. Some preparation would be possible though, like the global tsunami warning system demonstrates (Bernard & Titov, 2015). If an asteroid impact were to happen nonetheless, and if part of mankind were to survive, we would certainly need to show resilience. Early discovery of a dangerous space-rock could give us some time for preparation and this might help us to recover from the damage and shorten the aftermath.

For now, in the midst of our current predicament, the Covid-19 pandemic, we need to worry about much smaller yet more likely major disasters with more means at our disposal to avoid them and, if all else fails, to mitigate them and control the harm and damage they might do.

Looking at the safety zoo, it would seem that dragons were suspected around the wild animal market but this danger was deemed unknown. It were grey mouses in local governments that accepted their risks and paper tigers looking away. In fact they were looking away from a dinosaur in the living room, the WHO, rendered powerless by many years of budget cutting. Many Western countries thought it were black-swans the Far-East was dealing with and – with SARS in mind - decided that it was highly unlikely such a pathogen would ever reach the West. It turned out this was an error of judgement since the world became quickly aware of a contagious elephant in the doctors’ room presenting a great threat to the global population.

The response observed in most countries to the emerging pandemic was like not moving out of the way while being in the path of a charging gray rhino. Several other countries did better by taking action immediately however, resulting in exceptionally low death tolls. Leaders in several other countries behaved more like an ostrich since they downplayed, denied or ignored the pandemic. The consequences of ineffective responses are exceptionally high death tolls.

These notions raise many questions by many people about what it takes to choose the right strategy for health, safety, vulnerable groups, critical functions, essential services and supplies, society and economy in relation to pandemic risk.

Although - at first glance - the Covid-19 pandemic first of all presents as a health crisis, we contend there is more to it than health, currently getting near to all of our attention.

From a safety management point of view the world is confronted with an unwanted event and huge adverse consequences: by June 10, 2020 the growing total death toll in over 190 countries passed 408,000 (WHO, 2020f, WHO, 2020) while societal disruption and global economic damage continue to develop.

2. Problem definition

Our current predicament, the Covid-19 pandemic, has an anatomy similar to that of major accidents such as the Bhopal-, Tsjernobyl- and Seveso disasters. There are multiple causal factors, important risks to consider, prevention measures to take and – in case all those fail – a well prepared repression system, consisting of preparation, emergency response and mitigation, to put in place.

Since several critical observations can be made originating from this background, we would like to explore in this study, learning from the current Covid-19 pandemic, the possibilities for applying and improving current safety management and risk control concepts to potential future pandemics. We do not distinguish between industrial-, chemical-, occupational-, environmental-, biological-, social or medical safety and -security since risk control touches upon many disciplines and expertise areas.

To this end we want to look at pandemics in general from the point of view of major accident hazard risk control, as it is in use in e.g. the chemical industry (EC, 2012), in health, safety and environment management systems in in hospitals (Pariès et al., 2019, Niv et al., 2017) and in live stock and breeding farms biosafety and biosecurity systems (Heckert et al.,2011).

This study centres on the following question:

What could have been done better in prevention and repression of the Covid-19 pandemic from a safety management and risk control perspective?

3. Research method

The overall design of this study follows the case study method (Yin et al., 2006). It consists of a sequence of steps to follow in the research process, here simplified from Eisenhardt (1989) to: design, data gathering from literature and observations, analysis and construction of a theoretical model and a critical reflection on the outcome. The latitudinal descriptive case study form we use requires a blue-print to provide a structure for data gathering (Yin et al., 2006). To this end we use a shortlist of aspects (Kohn, 1997), derived from a preliminary literature search.

The quality and validity of our findings are protected by using multiple, independent and peer-reviewed sources where available and by triangulation of data originating from different stakeholders (Mays & Pope, 2000).

Our research design consists of three main parts, each requiring different methods and techniques.

-

–

Literature search

Since a wide range of subjects is involved we explored literature in a series of separate searches using the scoping review technique (Smith et al., 2015). We started with a preliminary search to derive initial search terms. For the successive literature searches per subject we used a progressively extended set of search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria. The subjects are listed in the case study blue-print (see Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Case study blue-print - structure for data gathering and analysis.

| Literature data: | Our current predicament: the Covid-19 pandemic |

| Comparison of country responses and their effects | |

| Human behaviour in the face of exceptional danger | |

| Observations: | Critical observations from a risk management point of view |

| Opportunities for new preventive and repressive barriers | |

| Construction of a theoretical model: | Safety management and risk control methods |

| Pandemic scenario tree structure | |

| Barriers and support systems | |

| Integrated pandemic barrier model |

Several Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to protect the quality of the sources:

-

•

Primary peer-reviewed scientific sources from various databases and via reference listings

-

•

Secondary sources (Cronin et al., 2008) from government organisations and international institutions.

-

•

Tertiary ’Grey’ sources (Wessels, 1997) only if particularly relevant to the subjects.

-

•

Time period: 2000–2020, with a few exceptions for essential sources from before 2000.

-

•

We excluded publications only available in other languages than English and Dutch.

-

•

We screened sources found by means of the search terms and the in/exclusion criteria.

-

•

Search terms are successively derived from the sources found and different subsets of terms were used for each subject to ensure that important sources were included.

-

•

Databases used: Scopus, Medline, Google Scholar, Academia, Research Gate and associated proprietary databases.

-

–

Construction of a theoretical model

The risk management model we use in this study consists of three well proven elements:

-

•

a 6 steps risk awareness approach (De Oliveira et al., 2017, Enders, 2001; ISO 31000:2009),

-

•

a risk matrix based assessment system (ISO 31000:2009) and

-

•

a ‘bow-tie’ timeline/causality model (Léger et al., 2008, Khakzad et al., 2012).

These elements are generally accepted and widely used risk management techniques, and their combination enables mapping, analysing and comparing the outcomes of safety management and risk control approaches over time.

In support of the theoretical model we analyse the process observed as the current Covid-19 pandemic is unfolding. From our literature findings we deduce a series of generic pandemic scenario events, a range of countermeasures and a suite of supporting activities. The way we do this follows the steps in a meta-synthesis process (Croninet al., 2008, Polit and Beck, 2006).

-

–

Critical reflection

Comparing our ideals with observed practice is at the roots of every critical reflection no matter which belief, culture or emotion we come from. Learning from this comparison is what it is all about. To this end we compare observed practice and the ideal outcome according to a reference frame derived from the theoretical model.

Both the ideals and the outcome of our learning need to be constantly debated (Van Woerkom, 2010). Critical reflection is a sociological methodology often used in education but also in a variety of other disciplines (Fook et al., 2006). In practice the method in its simplest form consists of an introduction followed by two stages (Hickson, 2011): 1) deconstruction of reality and 2) reconstruction towards achieving the ideal outcome.

-

–

Limitations, reliability and validity

This study is limited with respect to the number of sources used versus the number of sources available. The data gathering via literature search started mid-april 2020 and continued up to june 3, 2020. By that time it became clear that the internet had grown considerably, reflected by an astounding 5,000,000,000 hits on Google. The scientific community had produced a huge number of papers, indicated by some 133,000 hits in Google Scholar, over 38,000 related research items on Researchgate.net and 16,500 related papers on Academia.edu, all found by searching on “Covid-19”. This overwhelming quantity of information defies any attempt to get an overview any time soon.

Since the exploratory work for this study was conducted by the authors and the danger of subjectivity can therefore not be simply discarded, we contend that the study is repeatable and verifiable. The reliability of each observation is based on multiple sources from before and after the start of the current pandemic. Our own interpretations are clearly identified as such by the choice of wording. We have chosen the research methodology and the time period for searching as described in the above, to ensure that our findings – learning from the current Covid-19 pandemic – are relevant to the framework of safety management based risk control of pandemics we propose.

4. Results

Our findings from literature search, observation, theory and analysis are described in the order of the subjects listed in the case study blue-print (see Table 1).

4.1. Literature search

Successive literature searches, closely following the blue-print, resulted in 141 sources in total. Among them are 106 primary scientific sources, 24 secondary sources, mainly from governmental and international institutions, and 11 tertiary sources, mainly from public media. From these sources we compiled a description of our current predicament, a comparison between country responses and their effects over the first 5 months, and a range of human behavioural reactions to danger.

4.1.1. Our current predicament: the Covid-19 pandemic

The increasing threat of viral pandemics, such as Spanish Flu (1918), Hong Kong Flu (1968), HIV/AIDS (1981), SARS (2002), Influenza A (2009), Ebola (2014), MERS (2015), and several others (Francis et al., 2019, Kain and Fowler, 2019, Jebril, 2020), has started a sense of urgency in emergency preparedness, especially in intensive care units (ICU) and in elderly homes. Preparation for a pandemic should include 1-coordinated surveillance in order to spot new viruses, 2-scalable emergency response, 3-quickly mass produced vaccines, 4-excellent communication, and 5-pre-approved research plans. Instead we “remain largely underprepared” (Kain & Fowler, 2019, p3-4). Spotting a virus requires a detection method, testing capability and a warning system (Kain & Fowler, 2019). The scalability refers to “Surge capacity of equipment, physical space, human resources, and system” (Sheikhbardsiri et al., 2017, p612). The later part of the period of some 100 years preceding our current predicament showed a series of multiple and returning H2N2, H1N1 and H3N2 pandemic influenza virus outbreaks (Francis et al., 2019). By 2013 the WHO had completed guidance on pandemic influenza emergency risk management (WHO, 2013). Preparing for a next influenza virus pandemic has been subject of WHO studies since. This resulted in a ‘preparedness framework’, issued in 2018 (WHO, 2018). Several countries have developed national derivatives of these plans. By 2019 the Dutch government finalized the latest National Safety Strategy (NVS, 2019), mentioning a large scale outbreak of an infectious disease, most likely an influenza pandemic. The plan revolves around “prevention, … defence” and “… reinforcement” and fits within the context of an integrated foreign countries and safety strategy (NVS, 2019, p8,9,28,39). These emergency preparedness plans focus on influenza viruses, which are returning and rather well known viruses (Francis et al., 2019), because of their assumed higher likelihood. More recent outbreaks from 2014 onwards however, were, unexpectedly, originating from the Ebola virus and the MERS corona virus.

Our current predicament is the November/December 2019 outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, causing the “Coronavirus Disease 2019”, abbreviated to “Covid-19”. The outbreak was first detected in December 2019 when several “clusters of patients with pneumonia of unknown cause that were epidemiologically linked to a seafood and wet animal wholesale market in Wuhan” were recognized (Zhu et al., 2020, p727; Hua & Shaw, 2020, p2). A timeline was established starting from the first reported case - patient 1 - on December 1, 2019 (Yan et al., 2020). Several detailed studies of the onset by Wu et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2020a, Wang et al., 2020b, Zhang et al., 2020a, Zhang et al., 2020b, did not lead to certainty about how the virus transferred to humans. Zhang, Li et al (2020) suggest that airborne transmission is the main culprit. Chinese officials, from the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, reported an epidemic by December 31 (Wang et al., 2020a, Wang et al., 2020b). Shortly after, the outbreak was reported to the WHO from Wuhan City, a major industrial centre in Hubei province, China, on December 31, 2019. After the declaration by Chinese officials of Covid-19 as the culprit on January 6, 2020, the genome sequence was published on virological.org (Zhang, 2019) a day later. By January 20, an international group of experts concluded that Covid-19 was similar to the SARS virus of 2002, that evidence was found of human-to-human transmission and that they had developed a diagnostic protocol, being tried out from January 13 onwards, to detect the virus in patients (Corman et al., 2020). The virus particles are some 100 nm in size, consist of RNA and proteins, are decomposing above 50 °C, and most likely originate from chrysanthemum bats or pangolin (Jebril, 2020, Zhou et al., 2020). On January 30, the WHO assigned the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) status to this outbreak, thereby underlining the international threat (Wang and Wang, 2020); RIVM, 2020). Initial average primary reproduction numbers R0 of 1.5 up to 4.92 were reported (Yan et al., 2020). On February 8 the WHO stated that the virus had reached 24 countries (Ghebreyesus, 2020). The WHO declared the outbreak a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020a, WHO, 2020). Almost 2 weeks before, on February 27, 2020 the first Covid-19 case was recorded in the Netherlands (RIVM, 2020). Next, the Dutch Government activated its national procedures, according to the Dutch National Safety Strategy plan (NVS, 2019), based on the Integrated Risk Analysis on National Safety (ANV, 2019), and started taking measures as described in the Concept Directive Covid-19 (RIVM, 2020). Slowly it became clear that some 40% of people diagnosed with the virus get mild symptoms, 40% get pneumonia, 15% experiences severe disease and 5% becomes critically ill and of those about one third die from it (WHO, 2020c).

By May 15, 2020 the estimated economic impact had exceeded the effect of the 2008 financial crisis and large parts of society and economy were “put on hold” (WHO, 2020c, p1). In many countries the pandemic was still rapidly developing but in a few countries across the globe the impact of the pandemic remained at least a factor 100 less in magnitude. At the same time, in more remote areas, such as the Solomon Islands in Oceania, thanks to travel restrictions, the virus had not yet arrived after 5 months since the onset of the pandemic beginning of December 2019. (WHO, 2020b, WHO, 2020, 2020c).

4.1.2. Comparison of country responses and their effects

While at the end of April 2020 China is recovering from the outbreak and is gradually bringing back Wuhan City to normal business levels, the pandemic is still sky-rocketing in other countries, at its peak in yet other countries, and in more remote places on the planet it has not even arrived. Astounding differences between countries are observed. Also the spatial variations within countries seem large, as illustrated by Covid-19 ‘hot spots’, for example in the Milan region in Northern Italy, New York State in the USA and the province Noord-Brabant in the Netherlands.

Although the death count per country heavily depends on the point it has reached in the process following the outbreak (WHO, 2020c), a comparison between countries is indicative when referring to approximately the same point. This provides a first glance at the effect their national strategies have had on the spread of the Covid-19 virus. Chang et al. (2020) identify 180 countries and territories struck by the pandemic by March 21, 2020 of which eight were most affected. Besides these eight countries, which are China, Italy, Spain, Iran, Germany, France, South Korea and the USA, also several other countries are of special relevance since they adopted clearly deviating strategies, obtaining clearly different results. These other countries are New Zealand, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Finland, Belgium and the Netherlands.

The Dutch National television channel NPO1 reported 5600 officially tested and recorded victims and another 3600 suspected Covid-19 victims on May 15, 2020, bringing the total estimated death toll on 9200. By June 10, 2020 the official death toll in the Netherlands reached 6031 (WHO, 2020f, WHO, 2020) leading to an estimated total of 10,000 Dutch Covid-19 victims.

Each country used a different strategy in their approach of the Covid-19 pandemic. Their strategies had different outcomes of death toll versus time. Fig. 1 shows that a quick response with mitigation measures makes all the difference. Where China, South Korea, New Zealand, Hong Kong and Taiwan managed to reduce spreading from the earliest moment on, leading to the number of local outbreaks and the resulting mortality counts staying low, the other countries showed prolonged and higher growth rates of death tolls (Wang et al., 2020a, Wang et al., 2020b, Khafaie and Rahim, 2020, WHO, 2020b, WHO, 2020, Moes, 2020, VPRO-OVT, 2020, WHO, 2020f, WHO, 2020). Table 2 shows that the elapsed time between the first Covid-19 related death in China on January 10, 2020, and in the first few of the other countries was some 40 days. PHEIC status was reported by the WHO on January 30, 2020 and pandemic status on March 11, 2020. Both came too late to be effective as a safety alert for countries still unaffected.

Fig. 1.

Initial development of Covid-19 pandemic death tolls in 14 selected countries. (Day 0 is set at the date of the first reported death, January 10, 2020).

Table 2.

Initial Covid-19 death toll reported from 14 selected countries.

| Country | Population | 2020 Death toll |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Million | 10-jan | 25-jan | 4-feb | 21-feb | 29-feb | 3-mar | 6-mar | 9-mar | 12-mar | 18-mar | 23-mar | 26-mar | 20-apr | 10-June | |

| China | 1386 | 1 | 56 | 425 | 2239 | 2838 | 2946 | 3045 | 3123 | 3178 | 3231 | 3276 | 3293 | 4642 | 4645 |

| Hong Kong | 7.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Italy | 60.5 | 1 | 21 | 52 | 148 | 366 | 631 | 2503 | 5476 | 7505 | 23,660 | 34,043 | |||

| Iran | 81.2 | 2 | 34 | 66 | 107 | 194 | 429 | 988 | 1685 | 2077 | 5118 | 8425 | |||

| France | 67 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 19 | 33 | 175 | 674 | 1331 | 19,689 | 29,234 | |||

| South Korea | 51.5 | 1 | 17 | 28 | 42 | 51 | 61 | 81 | 111 | 131 | 236 | 276 | |||

| USA | 327 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 11 | 31 | 58 | 420 | 884 | 34,203 | 110,770 | ||||

| Spain | 47 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 36 | 491 | 1720 | 3434 | 20,453 | 27,136 | |||||

| The Netherlands | 17.2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 43 | 179 | 356 | 3684 | 6031 | ||||||

| Germany | 82.8 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 94 | 198 | 4404 | 8729 | |||||||

| Belgium | 11.4 | 1 | 14 | 75 | 178 | 5683 | 9619 | ||||||||

| Taiwan | 23 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Finland | 5.5 | 1 | 3 | 94 | 324 | ||||||||||

| New Zealand | 4.9 | 1 | 12 | 22 | |||||||||||

A closer look at the individual countries shows that– apart from the speed of their first response – their strategies weren’t all that different.

China was the country where it all started (Yan et al., 2020) in Wuhan City in the Hubei region. After a period of increasing awareness of what had happened, the virus got out of control (Jebril, 2020, p5, 10-11). In the spring festival period with many millions gathering and travelling, the virus rapidly spread over China and abroad from Wuhan, a national and international transport hub (Peeri et al., 2020, Chang et al., 2020). China used the 2002–2003 SARS epidemic experience to mitigate the spread (Wang and Wang, 2020). Further worldwide spread followed due to global travel (Jebril, 2020, Wu et al., 2020). Italy was the first to receive the Covid-19 virus from China in Western Europe, quickly becoming the European ‘epi-centre’ (Jebril, 2020). Spain was experiencing an increasing case fatality rate (CFR) which was 6.2% (Khafaie & Rahim, 2020). Iran had no early official reporting in place and suddenly became the epi-centre in the Middle-East. Germany reported a low death toll among neighbouring European countries and compared to Italy and Iran. France was experiencing an increasing CFR which was 4.2% (Khafaie & Rahim, 2020). South Korea reported a low death toll by worldwide comparison, most likely related to this country’s high volume testing approach, previous experience with SARS, public places disinfection spraying, citizens wearing face masks, smart phone contact tracing and an information campaign (Moes, 2020). The USA reported the world’s highest death toll (WHO, 2020b, WHO, 2020). New Zealand quickly realized that cases were brought in from overseas. The country quickly closed its borders and went for a full lockdown, people were told to “stay within their bubble” and maintain a safe distance of 2 m. Taiwan reactivated the National Health Command Center, created after the SARS epidemic in 2004. The country chose very early on for a robust quarantine policy, based on backtracking peoples’ whereabouts the previous 14 days, and for using the previous SARS epidemic experience. Also with the use of face masks by the general public, disinfection spraying on public places, infrared thermometers at key locations in e.g. transportation hubs, and a risky places information campaign, a lockdown was avoided (Moes, 2020). Hong Kong adopted a – very effective – strategy similar to Taiwan. Also here the previous experience with SARS, and citizens wearing face masks were among the measures taken (Moes, 2020). Belgium initially reported a relatively modest death toll but then appeared to take over as fastest growing European country. This data artefact originated from non-tested suspect Covid-19 cases previously not being included in Covid-19 reports but only showing from total death statistics.

The Netherlands chose a social distancing strategy named intelligent lockdown (Rutte, 2020). It refers to both keeping critical functions in society running and to the general public keeping some freedom of moving about, as long as social distancing rules are being sufficiently respected. Like many other countries The Netherlands had the advantage of seeing the pandemic coming, but did not manage to have all countermeasures, materials and equipment in place before the pathogen had reached the country. It took until June 1, 2020 before large scale testing facilities became available (NOS, 2020). Quite the opposite occurred in Finland where a robust emergency preparedness facilitated the immediate introduction of pandemic countermeasures, leading to a low death toll (WHO, 2020f, WHO, 2020).

4.1.3. Human behaviour in the face of exceptional danger

The animals in the ‘safety zoo’ represent human conduct towards major safety risks which are not immediately recognized and do not occur very often. As we notice such threats in safety practice:

-

•

We suspect their presence, yet deem them as unknown

The world is a very complex, dynamic and changing place. Our knowledge is equally limited so, like in the distant past, we then “fear the dragons” (Elahi, 2011; Ale et al., 2020). Part of the world around us is unknown due of lacking awareness of its existence. For another part we know it is there but we have no knowledge about it. The mysterious part we are both not aware of and have no knowledge about is often referred to as ‘unknown-unknown’ or ‘unk-unk’ (Petersen et al., 2013). Unknown risk though is not as unknown as the ‘unknown-unknown’ category is sometimes presumed to be (Lindhout, 2019). Unknown does not always imply ‘not foreseeable’ (Ramasesh & Browning, 2014). Rather often safety improvement action can actually be taken instead of merely settling for ‘unknown’ and do nothing about such foreseeable danger (Lindhout & Reniers, 2017). This requires sufficient risk appetite however (Gjerdrum & Peter, 2011).

-

•

We are fully aware of them, yet accept their risk

In this probabilistic approach, as the probability gets closer to zero, extremely large consequences may become acceptable even without specific measures being taken. Simply following procedures by grey mouses can get us there (Verhagen, 2018). This implies that a large nationwide disaster scenario could be regarded as acceptable since its risk is properly controlled (HSE, 2001, p43). The probability may not really be zero though. Hence such a disaster is not completely ruled out and it must therefore be considered and accepted as a residual risk. We deem such risks to be unlikely.

-

•

We know about specific safety threats, yet regard them as highly unlikely or impossible

If we are not fully aware of how identified threats to safety might lead to unwanted events – because they are seen as too complex, interacting, multiple causal, dynamic, entropic (Mol, 2003) or they are depending on conditions – then we might one day suddenly, unexpectedly, be overwhelmed by a black swan (Taleb, 2007, Murphy and Conner, 2012, Ale et al., 2020).

-

•

Obvious safety risks actually cause damage, yet we do not act on them.

We build safety system routines to improve safety, yet we create bureaucracy while doing so.

Improving on safety management systems in industry and health care may lead to paper tigers (Dekker, 2014). This makes safety management focus on going through the required administrative motions rather than keep awareness high to spot safety threats.

-

•

Everyone sees a known and feasible opportunity to improve, yet we pretend it doesn’t exist

A paradoxical observation, done by Cohen, 1998, Cohen, 2005, in a wider more general area than only safety management, shows that managers pretend known and major improvement potential, not to exist even though means to realize them are available. He coined this looking away from the “dinosaur in the living room”, the obvious next thing to do in order to make a leap forward.

-

•

We recognize big and emerging threats to our safety but we still don’t act

Pandemic risks are an example of a huge threat, known to have created damage in the past and expected to do so again in the future but is not receiving adequate attention so that prevention activities are in place and mitigation is well prepared. When Srivatsa (2018) mentioned the “Elephant in the Doctors Room” he was addressing the emerging danger of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections, said to be capable of killing 10 million people before the year 2050.

-

•

We are watching immediate lethal danger of epic proportion and hesitate to act

This means - as if the above was not enough to describe the frighteningly unresponsive human condition - we can even deny and ignore a big rapidly developing global disaster, out to destroy millions of us, closing in on us at high speed, and do not move “when a gray rhino charges” (Wucker, 2016, p6).

-

•

We watch the threat coming at us and freeze

People believe their eyes more than their ears. An unknown and invisible enemy is initially met with unbelief. Much like animals in nature, we are not only hesitant, scared and avoid engaging in a fight, but we can even freeze in the face of approaching danger (Sagliano et al., 2014). People sometimes appear to have ostrich bird -like ways to go about sudden threats.

4.2. Observations

4.2.1. Critical observations from a safety management point of view

Although disaster risk management, preparation and response were mentioned in the WHO plans for the next pandemic (WHO, 2013, WHO, 2018), the approaches presented by the many countries following their guidance showed a range of problems.

-

•

Prepared for influenza

We have all been preparing more for the next influenza virus outbreak rather than for a next new unknown virus pandemic outbreak. The majority of activities deployed for an influenza outbreak are valid for any virus outbreak (Kain and Fowler, 2019, Madhav et al., 2017). However, the Covid-19 virus differs from an influenza virus. Assumptions made in the emergency preparedness protocols may therefore not always be applicable, render some of the influenza specific preparation activities unusable and slow down the response since new measures need to be developed on the spot with limited knowledge about the pathogen. Recently, the WHO priority for research and development was placed at “medical countermeasures, including vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics” to cover this gap (WHO, 2020c, p15). Preparation for any virus might have brought us in a better position on e.g. detection method, pre-approved vaccine research, vaccine development, required hospital space, testing commodities, ICU staff and ventilator equipment (Kain & Fowler, 2019). Case fatality rates (CFR) of e.g. influenza-A, are between 0.011% (Dawood, 2012) and 0.1% (Anderson et al., 2020). Other viruses may have significantly higher CFR’s such as Covid-19 (2%), SARS (9.6%) and MERS (35%) (Yan et al., 2020, Peeri et al., 2020, Khafaie and Rahim, 2020). Also the initially observed primary reproduction number R0 of the Covid-19 virus (R0=~5) indicates it spreads between 2 and 3 times faster than influenza viruses (R0=~1.5) (Khafaie and Rahim, 2020, Jebril, 2020, Anderson et al., 2020). As CFR is clearly higher and bats (and perhaps pangolin) in the South-East Asian region are a reservoir of SARS-like Corona viruses (Li, 2005), the preparation for a pandemic of any virus would have been more substantial, and most likely this would have made us be more cautious, more keen to act and preparing more robust measures. In fact many animals are reservoirs of many pathogens (Han et al., 2015).

-

•

Confusion about the onset

We also argue that along these lines there is still much to investigate about the causal tree preceding the first confirmed case of patient-1 (Yan et al., 2020). Of course this requires full transparency of the events in the Wuhan region leading to this first case. Also a better understanding of how containment of the new virus was handled between December 31, 2019 and the January 18, 2020 record breaking Wuhan New Year celebration (Kynge et al., 2020) is needed. At that time the term ‘prevention’, as it was used by Wang & Wang (2020), was applied to stopping further infections in an ongoing pandemic. From a safety system point of view – regarding the pandemic in its entirety – this would have to be labelled ‘repression’ or ‘mitigation’. The word ‘prevention’ as used in safety management refers to all that is being done to avoid a first outbreak.

-

•

Lack of education and involvement of citizens and workers

Education would make a difference. Education increases awareness. Less unsafe behaviour would improve prevention. More acceptance of and better adherence to social distancing measures during the repression of a pandemic would be achieved. For example Chang et al. (2020) mention a home quarantine strategy which – if explained, adopted and implemented correctly – could help to reduce spreading the virus to other members of a household. The WHO (2013) seeks more alignment between their guidance and the many member states national disaster management structures. An example of a successful approach is found with the – in fact still ongoing – pandemic of the HIV/AIDS virus. A worldwide information program, comprising education and empowerment of the population groups most involved with the onset of this pandemic, and other groups affected later (Chin, 1990), was started some 4 years after the onset (Mann & Kay, 1991) by the WHO (1987), based on the knowledge acquired about the particular relevance of gender, sexual behaviour and education of citizens for the prevention of further spread of the disease (Chin, 1990, Dowsett et al., 1998, Gupta, 2000). Also in agricultural biosafety and biosecurity systems there is an acknowledged need for education and training among workers (Heckert et al., 2011). Hence: there is a need for education, training and empowerment.

-

•

Treating a continuous threat as a single event

If pandemics are to occur increasingly more often (WEF, 2019, Kain and Fowler, 2019, Madhav et al., 2017) they will become part of our daily lives even more as HIV/AIDS and influenza are today. Irrespective of the specific pathogen potentially causing a pandemic, several generic countermeasures could already be taken. Identifiable areas in the world having a spark-risk, i.e. where onset is more likely (Madhav et al., 2017) both preventive and repressive measures are necessary. Here, prevention would include e.g. preventive prophylaxis and spatial- and temporal segregation. The repressive measures required to quickly contain an outbreak in such areas could include investing in existing public health methods such as routine health monitoring, regular vaccination, detection activities, and emergency drills, but also new measures. Other areas may be more susceptible to spread risk, i.e. where the situation enables spreading more than elsewhere, necessitating other supplementary mitigation measures (Madhav et al., 2017). This continuous presence of routine pandemic prevention activities creates attention, awareness and caution among the general public and health care providers (Wang & Wang, 2020), especially in regions susceptible for spark-risk the onset of an epidemic or pandemic (Madhav et al., 2017). This compares to earthquake shelter-, fire evacuation- and cruise ship safety drills. An involved, educated and trained citizen can become partner in both the prevention and the repression of pandemics. Countries would become more resilient if many citizens take part in some form of volunteer disaster fighting (WEF, 2019). It would certainly help to satisfy the scalability requirement. Practice shows that Red Cross volunteers, former- or retired health care workers and many other groups, spontaneously and creatively display a plethora of activities to do just that.

-

•

Disregarding the need for resilience in societal design

A pandemic creates disruption in society and economy. That this will happen more often in the future is presented as an acknowledged fact (WHO, 2013, 2020c; WEF, 2019). Since it might happen this points at a Government responsibility for creation and safeguarding of societal resilience, a truly daunting task. Consecutive pandemics might not even allow a full societal recovery in between. This would have a profound impact on both long term global economic development and on social wellbeing and social stability in many countries affected. The WHO (2020c) points this out and individual countries are to take action. Businesses, buildings, schools, public space and transportation systems are not designed to accommodate for “… a sustainable, steady state [time period] of low-level or no transmission … in the absence of a safe and effective vaccine” (WHO, 2020c, p10).

If pandemics are recurrent, recovery periods in between are also. An agreed, prepared and detailed societal, economical and ethical post-pandemic recovery plan and practical preparation for resilience are missing. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, earlier economic, financial and political considerations have put priorities elsewhere in societies, leading to a slow response, to major logistical problems and little socio-economic resilience.

-

•

Poor national procedures

Consensus between neighbouring countries is lacking. This is leading to local, regional and country level differences, most noticeable in social distancing measures and emergency preparedness. The safety management aspects mentioned in the Dutch National Safety Strategy plan (NVS, 2019), i.e. identification, prevention, pro-action, preparation, response and aftercare as necessary, are not directly linked to pandemic risk control. When it comes to risk identification this is achieved via an Integrated Risk Analysis on National Safety, which is – in line with the WHO, 2013, WHO, 2018 – focusing on an “influenza pandemic” (ANV, 2019, p25). All other risk control aspects and activities to implement appropriate measures are covered by the Dutch Institute for Public Health and Environment (RIVM), as laid down in the Concept Directive Covid-19 (CDC19) guidance (RIVM, 2020). The word ‘prevention’ is used as a label on the protection of vulnerable groups and on individual citizen behaviour as to prevent further spreading of the influenza virus. The NVS, ANV and CDC19 are not aiming at avoiding a pandemic altogether and therefore do not deal with ‘prevention’ in the safety management sense. Pro-action is not mentioned. Preparation is detailed in a range of organisational measures in the CDC19 and response consists of a description of patient treatment from first detection, via home care, hospital care up to ICU care. Aftercare is not described and therefore - by default - assumed to be arranged via regular care.

-

•

Not building up an emergency stockpile and scalable local production capacity

At the end of April 2020, the measures applied in practice in The Netherlands consisted of personal hygiene, hospital staff wearing personal protective equipment and the public applying social distancing. Care professionals dealing with the most vulnerable group in elderly care institutions had no access to personal protection however. Health care- and infection case contacts tracing staff were a constraining factor. Scarcity of material and equipment supplies, led to criticality of hospital and ICU capacity, jeopardised the timely distribution of personal protection equipment in care institutions, and testing among the general public. Mainly due to privacy concerns, no “contactless temperature monitoring” and “contacts tracing phone-APP” were introduced in many countries, such as The Netherlands, in direct response to the “test, test, test” instruction coming from the WHO director-general Ghebreyesus (2020) and of the “detect, test, isolate, care, quarantine contacts” strategy (WHO, 2020c, p8-10). International press and digital media had shown the presence of anti-spreading measures in several countries already very shortly after the onset of the pandemic, e.g. face masks, infrared temperature sensors, drive through virus testing booths, disinfection spraying of public places and smart phone based contacts tracing methods.

In countries not having built-up an emergency supplies stockpile and not having production capacity locally available, the supply problems were paramount, including in China (Wang & Wang, 2020). These logistic problems have led to health professionals working without adequate personal protection and to the general public not contributing to reducing the R0 below 1.0 as much as would have been possible. These problems explain much of the death toll differences observed in Fig. 1.

-

•

No guidance for being responsive to needs of vulnerable groups

Vulnerable groups, whether due to age, other physical or mental diseases, to unhealthy or overcrowded living conditions e.g. in facilities for asylum seekers and prisons, or due to social isolation in health care facilities, to poverty or to low socio-economic status, all need special attention (WHO, 2020c, p11). No specific guidance was available with suitable well proven solutions and best practices derived from previous epidemics.

During previous epidemics the overwhelmed health-care system creates yet another vulnerable group: those in need of postponed treatment. Due to this, higher death rates were observed for other causes (Anderson et al., 2020). This underlines the need for preparedness for these groups.

-

•

Case history not recorded in detail

At first statistical data about the different health stages which persons with a diagnosed pathogen infection go through (Zhong, 2017) are highly uncertain, most so immediately after the onset. As pandemic spread grows, such data can provide useful records. Such records would gradually shed more light on the success rates of treatment options used in various countries. Accurately kept records also allow detailed analysis on vulnerability of specific social groups (Weiss, 2020).

However, as health systems in various countries were overwhelmed, their records became increasingly incomplete, rather than more accurate. Some countries did not keep records.

-

•

Early SWOT analysis

Wang & Wang (2020) published an early systematic analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) of the “Covid-19 epidemic prevention and control strategy” by the end of March 2020. Of the four highest priority improvements they identify, three are about emergency response and one is about strengthening the economic structure. Furthermore, various aspects of social security, psychological issues, economical damage and opportunities for education in relation to emergencies with infectious diseases were mentioned. Wang & Wang (2020, p8,11,12) do mention “prevention of public health emergencies” and describe such emergencies as a “threat to all human beings”. Practical issues they mentioned are: “weak wildlife market supervision”, “basic health security facilities lagging behind”, and “hazard risk assessments”. Although it is early days for a holistic SWOT analysis on the Covid-19 pandemic, we underline the necessity of further evaluation.

-

•

Criticality of leadership

Transactional leadership “aimed at an exchange of rewards for fulfilling expectations” (Grote, 2019, p.60) seems necessary. Switching between fixed and flexible attitudes, and between different safety management modes of operation (Pariès et al., 2019) are needed to restore society and economy after a disaster. To fully recover from a disaster, “putting back damaged systems to establish a new normal at least as reliable and robust as before, if not improved” is needed (Pettersen & Schulman, 2019, p.460,461).

The importance of leadership during a crisis cannot be underestimated. Henley & Roy (2020) wonder whether female leaders were more successful during the early part of the Covid-19 pandemic. They suggest that firm action (New Zealand’s premier Jacinda Ardern: “go hard and go early”) and an effective communication strategy (Jacinda Ardern: “stay home, save lives”) chosen by New Zealand, Taiwan, Denmark, Finland, South Korea, Norway, Iceland and Germany, were of paramount importance for adherence to social distancing measures. The question is whether the opposite was also observed: have male leaders done considerably worse? Henley & Roy (2020) point out that the performance of countries with the highest death toll per April 20, 2020, the USA (34,203), Italy (23,660) and Spain (20,453) (WHO, 2020b, WHO, 2020), would confirm this observation although clear examples of very effective male leadership also exist, since on the same date Vietnam (0), the Czech Republic (1 8 8), Greece (1 1 0), Australia (70) (WHO, 2020b, WHO, 2020) had managed the pandemic rather well. We contend that speed and quality of action and of communication determined success rather than gender of the leaders.

-

•

Lacking resilience

Wiig and Fahlbruch (2019,p.1) mention the range of related fields, the many definitions of resilience, and several challenges, a.o. the many theories and the lack of empirical evidence in several areas. One such area is the lack of knowledge about the role of stakeholders. Moser et al. (2019, p.21,26,27) point out that resilience as a concept gradually evolved from the “ability to bounce back”, via “coping mechanism”, via “capacity to adapt to impacts” and “prevention strategy” towards “system change” and “radical transformation”. Pettersen and Schulman (2019, p.460,461) see resilience as a means to “cope with unexpected events” and note that resilience is described in many ways, e.g. ”rebound”, “stretching” an organisation, “robustness”. The magnitude of disruption caused by an unwanted event determines the effort to neutralize the adverse effects, leading to resilience types, kinds, scales or levels (Macrae & Wiig, 2019, p.126) (Pettersen & Schulman, 2019, p.460,461). Woods (2015) describes resilience is as “sustainable adaptability”.Tiernan et al. (2019) suggest a nuanced exploration of the concept of adaptive resilience. Woods (2015) defines this as: ”a network architectures that can sustain the ability to adapt to future surprises as conditions evolve”.

-

•

Ethical concerns

The relatively short medical emergency phase after the pandemic onset is followed by a long mitigation phase, lasting until an effective vaccine becomes available. In many countries society builds up resistance to the constraints imposed on personal lives, business operations, leisure time and travelling. The behaviour of individuals not respecting temporary distancing and hygiene measures and individuals engaging in criminal activities such as providing sub-standard medical supplies or selling fake medicines, may require specific temporary legislation to allow adequate law enforcement. Governments could be tempted to hastily introduce new legislation without respecting democratic decision-making procedures, to introduce election driven aspects into implementation practice and not ensure a timely end to its being in force (Smits and Van Duijn, 2020, Jones, 2020).

Major ethical concerns emerge, not only with criteria to be used during triage when health professionals are suddenly facing limited health care capacity and medical supplies (Berlinger et al., 2020, WHO, 2007, WHO, 2008) but also with the constraints of fundamental rights, with a lack of democratic debate on proportionality of fines or imprisonment, with uncertainty about which precise behaviour causes the pathogen to spread, and about treating all citizens equal when taking away their livelihood, curtail exertion of democratic rights and limit access to health care. Even more ethical issues arise about criminalizing peoples’ proximity to loved ones, about focusing on physical health and ignoring mental health, police intrusion in private life, and even about messing with peoples’ zest for life. Health ethics aims to contribute to wellbeing, avoidance of damage, respecting autonomy and seeks justice in an inclusive way (Beauchamp and Childress, 1983).

4.2.2. Opportunities for improved or new preventive and repressive barriers

An inquisitive approach of prevention may lead to the discovery of new preventive barriers placed well before the onset of pandemics. Since within 4 months’ time a fully-fledged global Covid-19 pandemic emerged, we contend that practice has underlined that also opportunities for new repressive barriers, to be placed shortly after the onset, need further investigation. As the impact of a pandemic is large, we contend that continuous searching for new barriers, both preventive and repressive is justified. We have found several lines of thinking opening up possibilities for development of new barrier types.

-

•

Embrace the safety management paradigm

On February 8, 2020, WHO Director-General Ghebreyesus (2020) mentioned 216 health threat signals had the attention of the WHO of which Covid-19 was just one. Hence, the pandemic danger is both big and growing. Experts are pointing out that pandemics will occur more often in the future. Seeing pandemics as a “given” (Madhav et al., 2017) or as a “a continuum of pandemic phases” (WHO, 2013) distracts the attention away from the introduction of preventive countermeasures. Treating pandemics as a “medical emergency” (WHO, 2020c), may stimulate emergency preparedness and mitigation, but leaves prevention - in the safety management sense - out of scope.

Placing the focus of attention on repression implies looking less at what caused an event. Evidently these lines of thinking will result in avoidable repeats of the unwanted event. Only working on the repression aspect of pandemics implies that the great value of prevention is for a part ignored. As a consequence of that, education and training of people working with animals remain underutilized as a preventive means. Moreover, nobody in their right mind would knowingly want to accidentally start a global pandemic. There is much work to do in the “prepandemic period” (Madhav et al., 2017, p326). The current line of thinking does not prepare society for dealing with the social disruption and the huge effort needed for socio-economic recovery (WEF, 2019). We contend that safety management would be a better paradigm for dealing with pandemic risk.

-

•

Segregation

With the Australian mathematical model ACEMod, analysts managed to predict that school closures are not contributing much to the social distancing strategy, assuming compliance levels are above 70%. Also the ACEMod analysis results are pointing at a minimum requirement of 80–90% adherence to social distancing measures in order to effectively control the pandemic (Chang et al., 2020). With allowing the lower grade schools to re-open on May 11, 2020 the Dutch government took the first step on the path towards bringing society back on its feet. This was combined with a temporal segregation measure: half the kids in the mornings, half the kids in the afternoons. Extending early morning shop opening hours especially for the older more vulnerable age group is another example of age segregation.

Another strategy would be to quickly compartmentalize society in case of emergency, limit traffic between compartments and introduce robust surveillance. This would qualify as spatial segregation. One of the questions here is whether spreading of the Covid-19 virus could also be slowed down at intermediate distances, somewhere in between social distancing with short distances - 3 feet (WHO, 2020e, WHO, 2020), 1.5 m (RIVM, 2020), 6 feet (CDC, 2020) or 2 m (Jebril, 2020) - and closed borders with neighbouring countries at long distances, say 300 km. Such intermediate distances would be on the scale of a city or region. An in depth investigation of the effects of closing the perimeter around e.g. Wuhan City, Singapore and Hong Kong in the first months of 2020 could offer sufficient proof of the potential of such measures.

-

•

Embrace biosecurity and biosafety practices

Employers having workers in close contact with animals should comply with safe work legislation in all countries. The United Nations safe work branch, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in Geneva, issues best practice based guidance for safe work. The current guidance from the ILO, 2001, ILO, 2010 does not touch upon epidemic or pandemic risk or upon the principles of biosafety and biosecurity however.

Barker (2014, p16) describes a case where “10 infected animals crossed paths with 24,500 other animals” underway in the livestock trade in the UK during the 2001 Foot and Mouth Disease epidemic (Law, 2006). This example indicates that also animal-to-animal (A2A) transfer needs to be minimized during livestock production and transport.

In fact the adoption of biosecurity and biosafety principles will be essential for successful prevention of pandemics in all countries. This is most necessary in ‘spark’ prone regions in development countries (Madhav et al., 2017) where the international community can invest in long term biosecurity programmes. The cost of such programmes is dwarfed by the damage caused by a global pandemic. These programmes could set up biosecurity plans for small producers, assess risks, implement bio-safe working methods and put in place a monitoring and warning system, using veterinary control on animal isolation, sanitation and transport (Conan et al., 2012, Alhaji and Odetokun, 2011, Kimman et al., 2008, Barker, 2014, Cardona, 2008, Zhou et al., 2019, Gonzalez and Macgregor-Skinner, 2015).

-

•

Prepare for all known danger

It is known where the danger comes from: the biggest threats are the so called “select agents”, and they are of ”viral, bacterial, fungal, prions … [and other] origins” (Gonzalez and Macgregor-Skinner, 2015, p1015–1016; Selectagents.gov, 2020). Much is known about related virus families (Zhu et al., 2019, p732; Yan et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020). Pre-approved research plans (Kain & Fowler, 2019) and even intensified continuous research on these known sources of pandemic risk are appropriate and justified when considering the magnitude of damage caused by the global pandemic. Instead of preparing for influenza pandemic, the WHO could initiate worldwide cooperation in order to extend the scope of pandemics preparation activities to several other threats from the select agents list (Selectagents.gov, 2020).

-

•

Use of safety system failure indicators

Pandemic prevention, consisting of a chain of several preventive measures connected in series, can be assisted by listening to weak signals (Delatour et al., 2013) and early warning signals (Paltrinieri et al., 2019). Such signals indicate that the likelihood of an outbreak may have increased and that attention or action is needed. Ideally, if a procedural or technical measure in the chain fails, this would be detected and corrective action would be triggered immediately. While the other measures in the chain still prevent the onset of a pandemic, the failing measure could be reinstated. If the whole chain of measures fails, the pathogen emerges at the end.

Detection of such a system failure could be done by direct detection of the pathogen on contaminated personal protection equipment. Indirect detection e.g. by detection of infected people having symptoms, e.g. elevated temperature, has become a proven alternative.

The Covid-19 virus was found in waste water (Jebril, 2020), so could bio-sampling sewers be a way to detect and localize a zoonosis before an outbreak? Sniffer dogs can be trained to smell even intentionally hidden and well wrapped illegal substances (Barker, 2014). So could dogs, less vulnerable to the virus as they seem to be (Shi et al., 2020) be trained as reliable Covid-19 sniffers? The Nosais trial in France and in and other countries may provide the answer (Roe, 2020). Biosensors may offer an alternative technical solution for Covid-19 (Qiu et al., 2020). The development of a reliable detection method for a new pathogen takes time however (Corman et al., 2020).

Hence, failure detection earlier in the prevention part of the chain of events is needed. In practice that could be done by detection of ‘failures to perform’ of the successive measures lined up in the chain. As we have learned from man-made disasters with nuclear power plants and high-risk chemical plants, also our ways to go about handling animals could be made safer with extra layers of preventive and repressive measures (Vadimovna & Sergeevich, 2017). As this is a proven way to control risks with an unacceptably large potential impact, it may also be useful as a tool to control pandemic risk. In the chemical industry, a similar chain of measures, often referred to as concentric layers of protection (Baybutt, 2003, Vadimovna and Sergeevich, 2017). If the primary containment fails, there is a secondary containment protecting people and environment. This approach is used around many industrial high risk locations, and often combined with an emergency shut down (ESD) provision (Markowski & Siuta, 2017). Such failure detection and ESD can even be working automatically if suitable equipment is installed. Bio facilities could be treated in much the same way as high risk chemical facilities are (EC, 2012). This leads to the concept of a quarantine delay circle around a bio facility as a secondary containment measure.

5. Analysis and construction of a theoretical model

A pandemic is characterized by a sequence of events leading to adverse effects, disruption, socio-economic damage and a considerable death toll. We construct a theoretical model against the background of safety management methods and techniques such as scenario’s, fault-trees, feed-back and learning loops, safety barriers and systems in support of such barriers. We use the recent experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic.

5.1. Safety management and risk control methods

The risk management model we construct in this study is based on three well proven elements:

Firstly, risk management distinguishes several successive time phases associated with increasing awareness and moving towards action. There are many ways to do this though (De Oliveira et al., 2017, Enders, 2001; ISO 31000:2009). In this study we use 6 generally applicable risk awareness steps:

1-discovering a danger, 2-acknowledge it, 3-investigate and understand its nature, 4-assess its effect magnitude and evaluate the risk, 5-take appropriate preventive and repressive countermeasures and 6-evaluate incidents in support of learning and improvement.

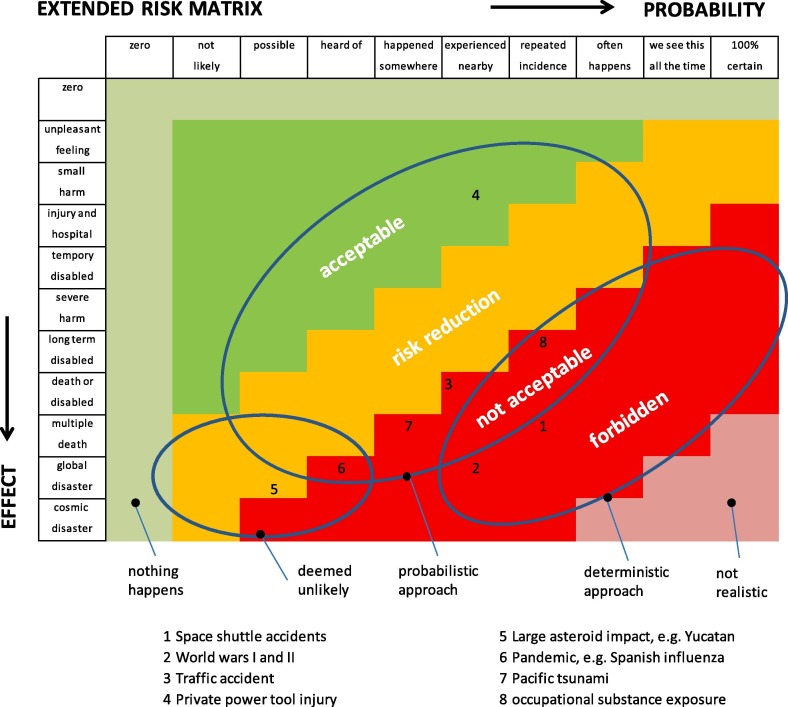

Secondly, risk management can be done in different ways, depending on the probability and effects of an unwanted event. This approach shows ‘risk’, the interrelation between likelihood and adverse effect. To this end such an event can be plotted in an extended risk matrix (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Extended risk matrix.

If the probability of an unwanted event is close to 100%, we avoid it by taking specific, strong and effective measures such as using other methods, prohibition by law or allowing prescribed safety measures only, often referred to as the ‘precautionary principle’. Are potential effects (very) large and uncertainties are large as well, then the ‘cautionary principle’ applies (Aven and Renn, 2018). These two constitute the deterministic approach to safety: making the unwanted event impossible.

If the event has a smaller probability we often use the risk matrix, a square with an effect scale versus a probability scale. An unwanted event can be plotted in this ‘risk field’. Within the framework of a safety management system, the ‘tiled’ centre area of this risk matrix can be used to show which effect and probability combinations are acceptable, which need risk reduction measures and which are not acceptable. This dual approach principle of ‘risk control’ is widely used in industry (ISO 31000:2009). At the left and top of the deterministic and probabilistic areas in Fig. 2 is a zone where probability and/or effect are zero so nothing will happen here. At the lower right is a zone which we consider as not realistic. At the lower left we situate the possible yet unlikely extreme events. Risk management can be applied, yet there is rather little we actually do in this corner. Here are opportunities for better repression but certainly also for better prevention and more education. Since prevention offers a very attractive perspective, we want to take this into account explicitly.

Thirdly, what happens before and after an unwanted event, follows one of many possible scenarios, involving several causal factors which may occur at the same time. The term ‘prevention’ is used to describe the risk control on what happens before an unwanted event takes place. The term ‘repression’ is used for minimizing all the negative effects which occur after the event. The event is situated in between cause and effect, hence the term ‘unwanted central event’ is used here.

Such central events normally have both multiple possible causes and multiple possible effects. An unwanted central event is therefore preceded by a causal tree and followed by a consequences tree, usually referred to as a ‘bow-tie’ because of its shape, see Fig. 3 . Thus far, as far as we can see, bowtie models have been introduced to manage Covid-19 risks for health and safety from a worker perspective (Wajidi, 2020, Manton et al., 2020) and from an organisation perspective (Protecht, 2020), but not from a global pandemic risk management perspective.

Fig. 3.

Bow-tie model and the safety hierarchy.

In this model, the unwanted central event, in fault-tree terminology also referred to as ‘top-event’, either happens or does not happen, depending on whether preventive barriers in the causal tree stop one or more causal factors from contributing to a pandemic scenario unfolding in time. In case the central event happens, repressive barriers are put in place to stop, mitigate and minimize the adverse effects.

Preventive and repressive barriers can be classified in several types: behavioural, human-hardware, hardware-human, active hardware, passive hardware (Li et al., 2020) and they are kept in place by supporting delivery systems – resources – within a safety management system context, such as leadership, communication, education, training, monitoring, inspection, maintenance and a right attitude of people towards safety. A feedback loop ensures that learning from unwanted events leads to system improvements via education and renewed risk assessment (Li et al., 2020).

Since prevention is not always perfect, and the central event can happen, ‘preparation’ is needed for foreseeable events. Thereto repressive barriers are put in place to prepare for emergency response, mitigation and avoidance of long term effects. What must be done depends on the risk inventory. If a risk is not identified there will be neither preparation of specific countermeasures, nor any prevention activities.

Emergency response is needed immediately after the event. A thorough preparation allows a fast and adequate response to the emergency situation after an unwanted, yet anticipated event occurs.

Ideally, an effective prevention does not allow the unwanted event to happen in the first place. Analyses of the root causes of previous incidents feed improvement of preventive barriers. Evaluation of the aftermath of an event feeds the improvement of the effectiveness of all barriers, including the repressive ones.

This socio-technical modelling technique is used in industrial major accident hazard risk control practice and enables safety analysts to graphically display causality, scenario’s, barriers and time-lines in an integrated way (Léger et al., 2008). In this framework further analysis is possible using static probability data on events and barriers in the causality tree. Such analysis can also be made dynamic by replacing the static data by model analysis using real time measurements of process parameters as inputs (Khakzad et al., 2012). For the purpose of mapping and analysing the effects of barriers against any pandemic while it is unfolding, combinations with Bayesian networks and agent based spreading models (Chang et al., 2020) may become powerful tools. Data about the pathogen properties could be included as they are becoming available in such a model, predicting the outcome of mitigation strategies.

5.2. Generic pandemic scenario

If not prevented, a pathogen coming from an animal may infect a human. In this way one person may get a zoonosis. This single case may lead to human-to-human (H2H) transfer. More persons may become infected. If not contained this case can become an outbreak. If not quickly stopped it may reach the stage of a local epidemic. If not mitigated sufficiently the pathogen may cross country borders and become a global pandemic. All these events together constitute a pandemic scenario, unfolding over time. We designed a generic pandemic scenario to be used in our model. It is built-up in line with the sequence of events unfolding in the current Covid-19 pandemic. The generic scenario starts from root causes as identified from literature. Even though root causes may for a part reside in political, cultural, religious, traditional and economical realms, certainly all of them are worth a closer look from risk management point of view. Important trends contributing to pandemic risk are population-growth, more deforestation, more living in cities, now 55% and in 2050 some 68%, and more travelling across the globe (WEF, 2019, Kain and Fowler, 2019).

5.3. Barriers and support systems

Limiting animal-to-human (A2H) contact transfer risk is an important preventive measure (Chang et al., 2020, WHO, 2020b, WHO, 2020. If human-to-human transfer (H2H) occurs, the risk of epidemic or even pandemic spreading becomes manifest, necessitating “increased epidemiologic surveillance and monitoring” (Peeri et al., 2020, p8). Infection can continue with human-to-animal (H2A) transfer, like the recent case at two Dutch mink farms LNV (2020) where minks, cats and a dog were infected. On May, 20, 2020 the Dutch news media reported a case of A2H transfer back from the minks to a human, demonstrating the risk of creating new pathogen reservoirs in animals. On June 3, 2020 the Dutch Government started to destruct all minks at infected farms. This vulnerability of several domesticated animals was discovered recently (Shi et al., 2020, p3). The risk of infection could even involve plants (Heckert et al., 2011). The Covid-19 virus has already been detected in waste water (Jebril, 2020). It would seem that distancing and other spread reducing measures should be applied to animal-human contacts too. Jebril (2020, p5, 10-11) lists repressive measures on four geographical levels: Global: travel restrictions; National: government border control, keep vulnerable population safe from infection, reduce transmission; Local: quarantine Covid-19 cases (14, 18 or 21 days), in hospital: isolate Covid-19 cases, safe Covid-19 case burial practice, safe Covid-19 contaminated waste disposal (WHO, 2020d); Personal: hand washing, safe coughing/sneezing, wearing face mask in public, keep 2 m distance, keep away from Covid-19 cases (infected people). Di Gennaro et al. (2020) list several more personal measures: refrain from touching eyes, nose, and mouth, in case of symptoms seek medical care early, and follow advice given by your healthcare provider. The first response should be as fast as possible (Jebril, 2020). Turning back part of the transfer reduction measures during mitigation too early may trigger an uncontrolled second wave of infection cases (WHO, 2020c).

We extracted 204 text fragments from the literature sources used in this study. These fragments are describing conditions, events, required knowledge, listing emergency preparedness activities and needs and mitigation issues concerning our current predicament, the Covid-19 pandemic. Thematic analysis according to the meta-synthesis process (Croninet al., 2008, Polit and Beck, 2006) was then used to identify supporting systems, unwanted events in a generic pandemic scenario and barriers capable of stopping the scenario at a particular point from progressing any further.

5.4. Integrated pandemic barrier model

The combination of these three model elements and the meta-synthesis into the integrated pandemic barrier model we constructed is shown in Fig. 4 . The horizontal time scale is composed of the 6 steps and the bow–tie time scale. The model is integrated because we merge three safety models and use the sequence of events observed during the Covid-19 pandemic as it unfolded starting from December 1, 2019. The model is also about barriers since it is explicating and interrelating countermeasures of many different kinds. This model provides an overview of what may happen between root causes and long term effects from a safety management and risk control point of view. The pandemic scenario in Fig. 4 is starting from the position of the country having the first outbreak. This country is the origin of the pandemic. The scenario is – though inspired by the current Covid-19 pandemic events – not limited to a specific pathogen.

Fig. 4.

Integrated pandemic barrier model.

There is not just this first central unwanted event to consider. In each country where the pathogen first arrives there is another one. Each successive country will have a longer time advantage if the country of origin quickly issues an international alert.

The unwanted event in our model is therefore placed at the first local outbreak. This is the point in the pandemic process where an infection may either come from a local outbreak in the country of origin as shown, or from an infected person arriving from another country. The model structure can be used for any outbreak of any pathogen.

Our approach is complementary to the mathematical modelling of geographical infectious disease spreading over time, such as ACEMod (Chang et al., 2020), based on analysis of complex human behaviour in space and time and calibration with epidemiological case data (Schoenberg et al., 2019). Recursive patterns (Gouyet, 1996) are observed both in pathogen spreading (Hohl et al., 2016) and in the complex human behaviour in society (Vazquez-Prokopec et al., 2013). Prediction and evaluation of mitigation strategies requires sophisticated mathematical models (AlSharawi et al., 2013, Chang et al., 2020). Such mathematical models show their strengths starting from detection of an outbreak onwards to mitigation and emergence of a pandemic (Siettos and Russo, 2013, Zamba et al., 2013) The integrated pandemic model, as developed in this study (see Fig. 4), provides an overview of all possible barriers in the pandemic scenario and shows the causal tree and its opportunities for prevention. It shows the safeguarding of operational readiness of barriers by supporting systems.

Pathogen spreading goes on during the mitigation of a pandemic. This may cause ‘flares’, i.e. local outbreaks which may develop into a second wave and even multiple waves. Each new infection case, e.g. a first case in a country travelling in from abroad, comes in as ‘Patient-1′ and brings the scenario at the unwanted central event of the pandemic scenario.

6. Critical reflection

In the model proposed by Hickson (2011) the text in the previous sections in this study is the introduction to the two stages below.

Stage 1-Deconstruction – understanding how an event came about, its elements, what happened and why.

Any pandemic will come about via the generic pandemic scenario shown in Fig. 4. Our current predicament, the Covid-19 pandemic, here used as an example, is the resulting effect of barriers failing in a series of 5 consecutive events:

1-Root causes: local traditions, unawareness of biohazard risks, travelling across the globe, pathogen reservoirs in animals. These lead to:

2-Causal factors: people close to animals, food and hygiene habits, people close to people. These lead to:

3-Transfer from/via animal to a human: A2A, A2H, single case zoonosis. This leads to:

Transfer between humans: H2H, local outbreak. This leads to:

4-Epidemic: infected people, pathogen transfer. This leads to:

5-Pandemic: treatment, quarantine, unnoticed spreading, epidemic reaching other countries. This leads to:

6-Adverse effects: most of the health, social and economic effects in the scenario are observed. Vaccine induced immunity is not observed, since no vaccine is available. A second wave is not (yet) observed, although there were several new local outbreaks (status per May, 11, 2020).

Stage 2-Reconstruction – building the event up from altered elements and compare the outcome to reality.

If this scenario would be subject of robust risk-control all successive scenario events have barriers:

-

•

Biosafety education of people working with animals would create awareness about biohazard risks and about safe behaviour.

-

•