Abstract

Purpose:

As disparities in rural-urban cancer survivorship rates continue to widen, optimizing patient-provider communication regarding timely follow-up care is a potential mechanism to improving survivorship-related outcomes. The current study examines sociodemographic and health predictors of posttreatment patient-provider communication and follow-up care and associations between written communication and timely follow-up care for cancer survivors who identify as rural.

Methods:

Data were analyzed from posttreatment cancer survivor respondents of the Illinois Rural Cancer Assessment Study. The current study tested associations between sociodemographic variables and health factors on the quality of patient-provider communication and timely posttreatment follow-up care, defined as visits ≤ 3 months posttreatment, and associations between the receipt of written patient-provider communication on timely posttreatment follow-up care.

Results:

Among 90 self-identified rural cancer survivors, respondents with annual incomes < $50,000 and ≤ High School diploma were more likely to report a high quality of posttreatment patient-provider communication. Posttreatment written communication was reported by 62% of the respondents and 52% reported timely follow-up visits during the first 3 years of posttreatment care. Patients who reported receiving written patient-provider communication were more likely to have timely posttreatment follow-up care after completing active treatment than patients who had not received written patient-provider communication.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest that written patient-provider communication improved timely follow-up care for self-identified rural cancer survivors. This research supports policy and practice that recommends the receipt of a written survivorship care plans. Implementation of written survivorship care recommendations has the potential to improve survivorship care for rural cancer survivors.

Keywords: cancer survivors, disease management, health communication, rural health, survivorship

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) has estimated that by 2029, the proportion of cancer survivors in the United States will increase 29%, resulting in 21.7 million cancer survivors.1 Partially due to the emergence of new cancer treatment options, cancer patients are more likely to survive longer beyond treatment.2 In addition to advancements in cancer treatments, effective patient-provider communication is a major facilitator for optimizing survivorship outcomes.3–5 Communication including, but not limited to, a treatment summary, information on the possible late-term effects of treatment, recommended follow-up screenings to monitor recurrent cancers, and a communication plan between health care providers show promise of improving a patient’s understanding of their survivorship care and the potential to improve patient-reported survivorship outcomes.4,5 Consequentially, a poor understanding of the utility of posttreatment survivorship care can be a barrier to adequate survivorship care, as patients may delay the initiation of or reduce adherence to follow-up care screening for recurrent cancers, lack knowledge of the long-term effects of treatment, and have unaddressed psychosocial (ie, emotional and social) supportive care needs.6–9 Across health care systems and cancer types, posttreatment patient-provider communication is not standardized, and such heterogeneity in communication can increase survivorship risks associated with poor management of posttreatment care.8–12 Cancer survivors who receive their care at settings that adhere to the Commission on Cancer (CoC) guidelines are required to receive a survivorship care plan.13 Yet, many cancer survivors, such as those treated in non-CoC centers, face inequities in communication of survivorship care plans.14 This heterogeneity in care can contribute to disparities in long-term survivorship outcomes.

Addressing posttreatment survivorship care, including what are effective modalities, is an emerging priority for underserved communities, including rural cancer survivors. Rural cancer survivors have poorer cancer-specific survival rates than their urban counterparts.15,16 These survival rates are influenced, in part, by challenges pertaining to the geographic isolation of rural communities, additional cost burdens of traveling long distances to see specialty providers, and the need to access resources in urban areas.17,18 Added to the challenges associated with remote living, patients from or near rural areas are at a greater risk of poorly understanding the utility of survivorship care planning. Cancer survivors and caregivers of cancer patients report a moderate to low understanding of the posttreatment survivorship care recommendations from their health care providers.9,19 However, patient-provider communication about the survivor’s posttreatment care needs can improve the quality of the posttreatment patient-provider communication and survivorship outcomes, such as timely follow-up care.7,20

As it relates to optimizing posttreatment survivorship communication and the subsequent timely follow-up care for rural cancer patients, preliminary research is necessary to identify the quality and content of posttreatment survivorship communication between rural survivors and their providers. First, evidence of sociodemographic predictors of effective patient-provider communication and subsequent associations between effective patient-provider communication on cancer screenings and treatment initiation are known.21–23 In addition, sociodemographic associations between high-quality patient-provider communication regarding survivorship and timely follow-up care are unknown. Second, considering that survivorship communication is not standardized, there is a need to characterize and quantify elements of posttreatment survivorship communication of rural cancer patients and the most effective mode to present this information to improve timely follow-up care.

Given the challenges faced by rural cancer survivors to adhere to timely posttreatment follow-up care, optimizing patient-provider communication and understanding the best mode of delivery for patient-provider communication are critical to improving rural survivorship care. This information has the potential for reducing cancer survivorship disparities experienced by rural cancer survivors. The current study contributes to the existing literature by examining the following among cancer survivors that identify as rural dwellers: 1) sociodemographic and health predictors of posttreatment patient-provider communication and timely follow-up care, and 2) different components of patient-provider communication (quality, mode of delivery) in relation to timely follow-up care.

Methods

Parent Study

The Illinois Rural Cancer Assessment (IRCA) study is a statewide cross-sectional assessment examining mental and physical health status and functioning among rural cancer survivors and caregivers (N=227). This study was approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board and University of Illinois Cancer Center Protocol Review Committee.

Recruitment Procedures

Research staff at the University of Illinois in Chicago coordinated all recruitment efforts conducted in rural counties across Illinois. To note, most research staff did not receive monetary compensation for their time. Recruitment occurred in multiple waves. First, the study team attempted but was unable to partner with state cancer registries to recruit participants. Given this, Wave 1 (January 2017 – February 2018) recruitment efforts included community outreach methods from study staff in Chicago with 152 rural clinics, 120 health departments/government-funded health agencies, 16 academic institutions, and 79 community organizations (eg, churches). Willing partners received paper and electronic flyers, which could be distributed through listservs, social media, and websites. We also specifically tailored flyers (eg, pictures of male and racial/ethnic minority survivors) and distributed them to organizations with a substantial number of men and racial/ethnic minorities (eg, VA hospitals, African American churches). Recruitment partners who volunteered and distributed information did so without monetary compensation, due to restricted funds from this intramurally funded study. Recruitment partners were, however, able to promote their organization through the study team’s monthly newsletters and were able to solicit study team members for talks on rural cancer disparities for their constituents, as was of interest. In Wave 2, we expanded our recruitment efforts to respond to slower than expected recruitment rates from Wave 1. Wave 2 (March 2018 – September 2018) recruitment used commercial lists of 1,558 landline and 2,056 cellular telephone numbers within the 63 rural counties (RUCC=4-9) in Illinois, as well as 1 adjacent metropolitan county with fewer than 250,000 residents (RUCC=3). Research personnel started by calling phone numbers from the counties with the highest proportion of African American residents, and then they moved on to counties with the lowest proportion.24 Purchase of commercial lists was considered the optimal strategy for attempting a wide reach of this small, widely dispersed population across multiple rural communities with minimal funds. This strategy may, however, have been too broad, as we were unable to specify telephone lists to cancer survivors. In terms of participant compensation, participants could receive $15-$25. Compensation was increased by $10 during Wave 2, when we modified the consent process to include an opportunity wherein participants could be re-contacted in future survivorship studies.

Inclusion Criteria

Eligible individuals were self-reported as 18 years or older, a cancer survivor or a caregiver of a cancer patient, and self-identified as a resident of a rural Illinois county.

Exclusion Criteria

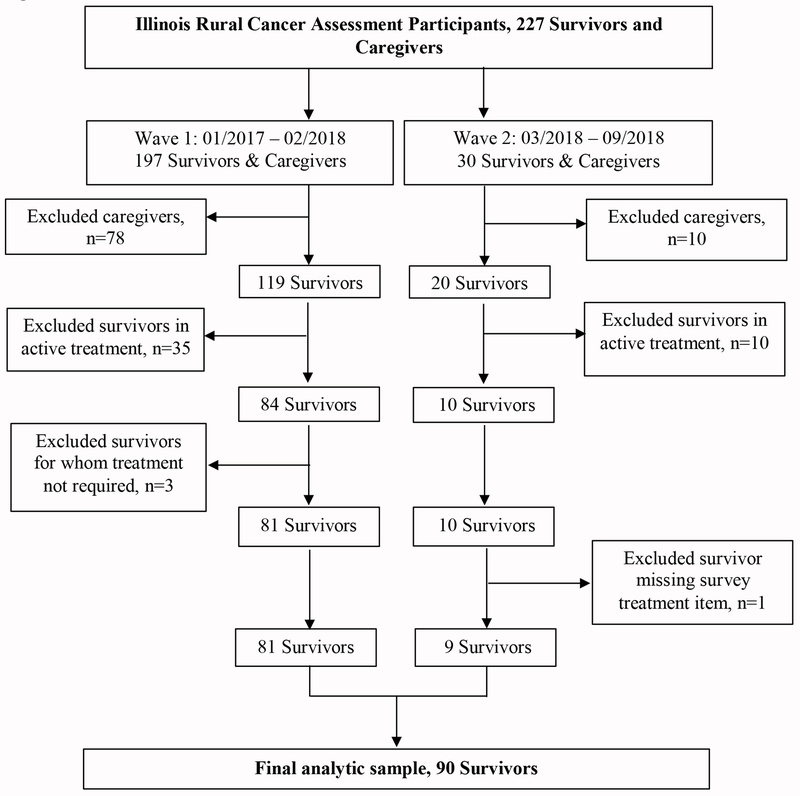

This study’s focus was on cancer survivors’ posttreatment communication. We did not recruit study dyads or collect data on survivors’ posttreatment experiences from caregivers. We recruited caregivers for the larger study to understand their own unique experiences as caregivers and not to provide patient data for this study (ie, patients’ timely follow-up care). Therefore, we excluded caregivers (n=88) from the current study. Also, respondents in active treatment (n=45), those that did not require treatment (n=3), and one individual who did not complete the posttreatment follow-up questions were excluded (Figure 1). Following the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship25 definition, cancer survivors were cancer patients in the posttreatment period to end-of-life.

Figure 1:

Illinois Rural Cancer Assessment Enrollment Flow Chart

Survey Procedures

After screening and providing informed consent, respondents had the option to complete the survey either online, by telephone, or by self-administration with an additional option to return the survey by mail or in-person at a cancer-related event. The duration of the survey was approximately 75 minutes. Attrition or partial survey respondents appeared relatively low, with 99% of survivors answering the last 5 questions.

Measures

Patient-provider communication quality was measured with a 4-item survey instrument from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey’s (MEPS) Experience with Cancer Care section to measure patient-provider communication quality.26 Patient-provider communication quality items included discussion items on 1) regular follow-up care and monitoring, 2) late or long-term side effects of cancer treatment, 3) emotional or social needs, and 4) lifestyle or health recommendations (Table 1). The type of provider was not specified for each item. Traditional scoring for this survey includes a 3-category ordinal variable, including High (≥ 3 “discussed in detail” responses and 0 “did not discuss” responses); Medium (other combinations of “discussed in detail,” “briefly discussed,” and “did not discuss” responses outside of combinations specified for High and Low Quality); and Low (≥ 1 “did not discuss” and ≤ 1 “discussed in detail” responses). Table 1 reports the frequency distributions of individual items. Based on preliminary analyses, the composite variable was dichotomized to be High or Not High (Low/Medium). Timely Posttreatment Follow-Up was defined as follow-up care by 3 months of posttreatment. Clinical implications, such as an increased likelihood of cancer recurrence and decreased survival rates resulting from delays in follow-up care are reported as early as 3 months posttreatment. The authors chose a threshold of 3 months for timely follow-up treatment because of its clinical significance.27–29 Timely posttreatment follow-up was measured with a single item from the MEPS Cancer Survivor Supplement.26 Survivors were asked about how often they visited the doctor for follow-up appointments during the first 3 years after completion of treatment. A dichotomous variable indicated if the follow-up was greater than 3-months, or less than or equal to 3 months.

Table 1.

Frequency Distribution of Individual Items in Patient-Provider Communication Instruments (n=90)

| Patient-Provider Communicationa Quality | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Discussed the need for regular follow-up care and monitoring even after completing your treatment? | ||

| In detail | 72 | 80% |

| Briefly | 14 | 16% |

| Not at all | 4 | 4% |

| Discussed late or long-term side effects of cancer treatment you may experience over time? | ||

| In detail | 38 | 42% |

| Briefly | 31 | 34% |

| Not at all | 21 | 23% |

| Discussed your emotional or social needs related to your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment? | ||

| In detail | 29 | 32% |

| Briefly | 28 | 31% |

| Not at all | 33 | 37% |

| Discussed your lifestyle or health recommendations such as diet, exercise, or quitting smoking. | ||

| In detail | 42 | 47% |

| Briefly | 37 | 41% |

| Not at all | 11 | 12% |

| Written Patient-Provider Communicationa | ||

| Written summary of all cancer treatments | ||

| Yes | 38 | 42% |

| No | 52 | 58% |

| Written summary of recommended follow-up care | ||

| Yes | 62 | 69% |

| No | 28 | 31% |

Type of provider was not specified.

Covariates included demographic, socioeconomic, rurality, cancer-related, and other health factors using items from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System,30 the MEPS Cancer Survivor Supplement,26 Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS),31 and the Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire.32 Demographic factors included age, gender (male/female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white/other), and marital status (married/non-married). Socioeconomic factors included age (continuous), education (< Bachelor’s/ > Bachelor’s), annual household income (< $50,000/ > $50,000), and private insurance (yes/no). Rurality was defined by RUCC (1-9). Cancer-related factors included cancer site (breast, gynecological, digestive, skin, lymphoma, other) and time since last treatment (< 5 years/ > 5 years). For treatment-related symptoms, we calculated the Global Distress Index score (possible range = 0-4), which was the average of 24 symptom scores that incorporated presence (yes/no), frequency (rarely, occasionally, frequently, almost constantly), and associated severity/distress (not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much) during the past week. Other health factors included current tobacco use (yes/no) and the number of lifetime comorbidities.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted in SPSS 25. First, missingness and descriptive statistics were assessed for the study sample. Given the relatively low amount of missingness, single imputation was conducted. Second, a bivariate analysis using chi-square tests (gender, race, marital status, private insurance, cancer sites, current tobacco use), independent t-tests (age, treatment-related symptoms, number of lifetime comorbidities), and Mann Whitney U tests (income, education, rurality) characterized relationships between demographic, socioeconomic, rurality, cancer-related, and other health factors with posttreatment patient-provider communication quality, written patient-provider communication, and timely follow-up care. Third, we conducted multivariable logistic regression models to examine the relationship between posttreatment patient-provider communication quality, written patient-provider communication, and timely follow-up care in crude models and Type III models including different domains of covariates (demographic factors, socioeconomic factors, degree of rurality, cancer-related, other health-related factors). For these models, we report likelihood ratios to compare model fit between crude models and models adjusting for different types of covariates. Due to sample size, we did not conduct a full model including all covariates. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted, wherein crude and adjusted models were replicated with non-imputed data only; with imputed data from Wave 1 respondents only, to address for effects of recruitment strategies; and with imputed data among respondents in non-metropolitan counties (RUCC 4-9). We do not report findings when including Wave 2 respondents only or respondents from metropolitan counties (RUCC 1-3) due to small subsample sizes.

Results

Sociodemographic and Health Predictors of Posttreatment Patient-Provider Communication and Timely Follow-up Care

The current study elucidated patient-provider communication data from 90 cancer survivors. Table 2 shows associations between demographic, socioeconomic, rurality, cancer-related, and other health-related factors and the quality of posttreatment patient-provider communication, written posttreatment patient-provider communication, and timely follow-up care. There were relatively low levels of missing data (≤ 1%), except for income and cancer sites, wherein 7% of the sample did not provide the data. Most respondents were 64 years or younger (71%). Most of the overall sample was female (82%), non-Hispanic white (93%), married (73%), had private insurance (61%), and lived in a non-metropolitan county (59%). Half of the overall sample had a Bachelor’s degree or greater and about half of the population (51%) had a household income of < $50,000. With regard to cancer-related and other health factors, breast cancer was the most reported primary cancer site (34%). The average score for the Global Distress Index was 0.76 (SD: 0.82). Most respondents had their last treatment more than 5 years after completion of the survey (52%). Approximately 11% of the sample currently used tobacco. The average number of lifetime comorbidities was 5.77 (SD: 3.57).

Table 2.

Study Sample Characteristics by Posttreatment Communication and Follow-up Care Utilization (N = 90)

| Quality of Patient-Provider Communication | Written Communication | Posttreatment Follow-up | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n= 90) |

High (n = 33) |

Not High (n=57) |

All (n=34) |

Not All (n=56) |

3 Months (n= 47) |

<3 months (n = 43) |

|||||||||||||

| DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS | Missing (%) | n | % | n | % | n | % | P value | n | % | n | % | P value | n | % | n | % | P value | |

| Agea | 0 | .70 | .29 | .29 | |||||||||||||||

| ≤53 years old | 34 | 38 | 14 | 42 | 20 | 35 | 10 | 29 | 24 | 43 | 21 | 45 | 13 | 30 | |||||

| 54-64 years old | 30 | 33 | 11 | 33 | 19 | 33 | 14 | 41 | 16 | 29 | 14 | 30 | 16 | 37 | |||||

| 65-83 years old | 26 | 29 | 8 | 24 | 18 | 32 | 10 | 29 | 16 | 29 | 12 | 26 | 14 | 33 | |||||

| Sex | 0 | .22 | .10 | .72 | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 16 | 18 | 8 | 24 | 8 | 14 | 9 | 27 | 7 | 13 | 9 | 19 | 7 | 16 | |||||

| Female | 74 | 82 | 25 | 76 | 49 | 86 | 25 | 74 | 49 | 88 | 38 | 81 | 36 | 84 | |||||

| Race | 0 | .67 | .82 | .42 | |||||||||||||||

| non-Latino White | 84 | 93 | 30 | 91 | 54 | 95 | 24 | 71 | 42 | 75 | 45 | 96 | 39 | 91 | |||||

| Other | 6 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 29 | 14 | 25 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 9 | |||||

| Marital Status | 0 | .55 | .65 | .46 | |||||||||||||||

| Married | 66 | 73 | 23 | 70 | 43 | 75 | 24 | 71 | 42 | 75 | 36 | 77 | 30 | 70 | |||||

| Not married | 24 | 27 | 10 | 30 | 14 | 25 | 10 | 29 | 14 | 25 | 11 | 23 | 13 | 30 | |||||

| SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS | |||||||||||||||||||

| Educationb | 0 | .02 | .75 | .06 | |||||||||||||||

| <Bachelor’s Degree | 45 | 50 | 21 | 64 | 24 | 42 | 16 | 47 | 29 | 52 | 27 | 57 | 18 | 42 | |||||

| ≥Bachelor’s Degree | 45 | 50 | 12 | 36 | 33 | 58 | 18 | 53 | 27 | 48 | 20 | 43 | 25 | 58 | |||||

| Household incomeb | 7 | .04 | .01 | .11 | |||||||||||||||

| <$50,001 | 38 | 42 | 19 | 59 | 19 | 37 | 19 | 59 | 19 | 36 | 23 | 52 | 15 | 37 | |||||

| ≥$50,001 | 46 | 51 | 13 | 41 | 33 | 64 | 13 | 41 | 33 | 67 | 21 | 47 | 25 | 63 | |||||

| Private health care insurance | 0 | .71 | .73 | .46 | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 55 | 61 | 21 | 64 | 34 | 60 | 14 | 41 | 21 | 38 | 27 | 57 | 28 | 65 | |||||

| No | 35 | 39 | 12 | 36 | 23 | 40 | 20 | 59 | 35 | 63 | 20 | 43 | 15 | 35 | |||||

| RURALITYb | 0 | .12 | .47 | .14 | |||||||||||||||

| Metropolitan (RUCC 1-3) | 37 | 41 | 17 | 51 | 20 | 35 | 14 | 41 | 23 | 41 | 19 | 44 | 18 | 38 | |||||

| Non-metropolitan (RUCC 4-9) | 53 | 59 | 16 | 49 | 37 | 65 | 20 | 59 | 33 | 59 | 24 | 56 | 29 | 61 | |||||

| CANCER-RELATED FACTORS | |||||||||||||||||||

| Cancer sites | 7 | .94 | .91 | .18 | |||||||||||||||

| Breast cancer | 31 | 34 | 12 | 38 | 19 | 33 | 11 | 32 | 20 | 36 | 17 | 36 | 14 | 33 | |||||

| Gynecological | 8 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 12 | |||||

| Digestive | 8 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 12 | |||||

| Skin | 9 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 17 | |||||

| Lymphoma | 13 | 15 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 18 | 6 | 17 | 7 | 13 | 9 | 19 | 4 | 10 | |||||

| Other | 20 | 23 | 8 | 25 | 12 | 21 | 9 | 27 | 11 | 20 | 13 | 28 | 7 | 17 | |||||

| Range | M | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||||

| Treatment-related Symptoms | 0 | 0-3.32 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.87 | .28 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.79 | .41 | 1.05 | 0.88 | 0.43 | 0.62 | <.001 | |

| n | n | % | n | % | P value | n | % | n | % | P value | n | % | n | % | P value | ||||

| Time Since Last Treatment | 0 | .16 | .45 | .001 | |||||||||||||||

| <5 years | 43 | 48 | 19 | 58 | 24 | 42 | 18 | 53 | 25 | 45 | 13 | 30 | 30 | 64 | |||||

| 5+ years | 47 | 52 | 14 | 42 | 33 | 58 | 16 | 47 | 31 | 55 | 30 | 70 | 17 | 36 | |||||

| OTHER HEALTH FACTORS | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tobacco Use | 1 | .96 | .19 | .84 | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 11 | 12 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 13 | 32 | 94 | 46 | 84 | 6 | 13 | 5 | 12 | |||||

| No | 78 | 88 | 29 | 88 | 49 | 88 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 16 | 40 | 87 | 38 | 88 | |||||

| Range | M | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||||

| Number of lifetime comorbidities | 0 | 0-14 | 5.77 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 4 | .10 | 6.32 | 3.78 | 5.16 | 3.27 | .13 | 6.31 | 3.78 | 5.16 | 3.27 | .13 | |

Variables presented categorically to facilitate interpretability, but analyzed as continuous variables.

Variables presented categorically to facilitate interpretability, but analyzed as ordinal variables.

Significant associations (P < .05) are in bold. Non-significant associations (P < .10) are italicized.

As shown in Table 2, 63% of the respondents reported not having high-quality posttreatment patient-provider communication, 62% reported not receiving any posttreatment written communication, and 52% reported visiting the doctor > 3 months for a follow-up visit during the first 3 years of posttreatment care. More respondents with fewer years of education and lower incomes reported high-quality posttreatment patient-provider communication relative to respondents with more education and higher incomes (64% and 59%, respectively). Of the respondents receiving treatment within the last 5 years of completing the survey, 30% obtained timely follow-up care, whereas 70% of the respondents receiving treatment > 5 years after completing the survey received timely follow-up care (P = .001). Respondents reporting greater treatment-related symptoms were more likely to have received timely follow-up care (P < .001).

Relationships Between Posttreatment Patient-Provider Communication and Timely Follow-up Care

Across crude, adjusted, and sensitivity models (Table 3), respondents receiving written communication had greater odds of reporting timely follow-up care than those who did not receive written communication. Quality of patient-provider communication was largely not associated with timely follow-up care. Models adjusting for cancer-related factors appeared to exhibit a better fit than crude models most consistently, when analyzing imputed data, analyzing non-imputed data, and focusing on subsets of our sample. When focusing on self-identified respondents in rural counties (n = 53), similar patterns emerged regarding written communication and timely follow-up care. There were additionally inconsistent relationships regarding quality of patient-provider communication and timely follow-up; however, these patterns should be interpreted cautiously due to the sparse subsample size.

Table 3.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Models Examining Posttreatment Communication and Follow-up Care Utilization

| Crude Model | Model with Demographic Factors | Model with Socioeconomic Factors | Model with Residental County Rurality | Model with Cancer-related Factors | Model with Other Health-related Factors | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Fit | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value |

| -- | -- | -- | 4.32 | 2 | .12 | 2.92 | 3 | .40 | 0.66 | 1 | .42 | 20.51 | 3 | .01 | 5.52 | 2 | .06 | |

| Individual Predictors | ||||||||||||||||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Quality of patient-provider communication | 1.78 | 0.64, 4.96 | .27 | 1.65 | 0.57, 4.78 | .36 | 1.51 | 0.51, 4.45 | .46 | 1.92 | 0.67, 5.50 | .23 | 2.44 | 0.74, 8.05 | .14 | 2.25 | 0.75, 6.72 | .15 |

| Written communication | 4.29 | 1.52, 12.10 | .01 | 5.76 | 1.88, 17.66 | .002 | 5.25 | 1.71, 16.13 | .004 | 4.18 | 1.47, 11.87 | .01 | 4.28 | 1.31, 13.94 | .02 | 5.04 | 1.68, 15.12 | .004 |

| DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.97 | 0.93, 1.00 | .08 | |||||||||||||||

| Marital Status (REF: Not Married) | 1.92 | 0.65, 5.63 | .24 | |||||||||||||||

| SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Education (REF: <Bachelor’s) | 0.46 | 0.17, 1.26 | .13 | |||||||||||||||

| Incomea | 1.07 | 0.72, 1.57 | .75 | |||||||||||||||

| Private insurance (REF: No) | 0.69 | 0.25, 1.95 | .49 | |||||||||||||||

| RURALITY (REF: RUCC 1-3) | 1.48 | 0.58, 3.78 | .42 | |||||||||||||||

| CANCER-RELATED FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Breast Cancer (REF: No) | 0.96 | 0.32, 2.90 | .94 | |||||||||||||||

| Treatment-related symptomsa | 3.28 | 1.49, 7.23 | .003 | |||||||||||||||

| Time since last treatment (REF: <5 years) | 0.34 | 0.12, 0.98 | .05 | |||||||||||||||

| OTHER HEALTH FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tobacco Use (REF: No) | 1.57 | 0.37, 6.70 | .55 | |||||||||||||||

| Number of lifetime comorbiditiesa | 1.17 | 1.01, 1.35 | .03 | |||||||||||||||

| Models with Non-Imputed Data (n=83) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Model Fit | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value |

| -- | -- | -- | 4.89 | 2 | .09 | 1.76 | 3 | .62 | 0.53 | 1 | .47 | 25.99 | 3 | .002 | 3.72 | 2 | .16 | |

| Individual Predictors | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Quality of patient-provider communication | 2.54 | 0.48, 13.35 | .27 | 1.87 | 0.60, 5.79 | .28 | 1.79 | 0.57, 5.59 | .32 | 2.26 | 0.73, 6.98 | .16 | 3.03 | 0.80, 3.03 | .11 | 2.37 | 0.76, 7.40 | .14 |

| Written communication | 4.78 | 1.58, 14.48 | .01 | 6.89 | 2.04, 23.25 | .005 | 5.51 | 1.65, 18.37 | .005 | 4.56 | 1.49, 13.96 | .01 | 6.41 | 1.62, 25.40 | .008 | 5.55 | 1.73, 17.80 | .004 |

| DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.96 | 0.92, 1.00 | .06 | |||||||||||||||

| Marital Status (REF: Not Married) | 1.93 | 0.63, 5.93 | .25 | |||||||||||||||

| SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Education (REF: <Bachelor’s) | 0.54 | 0.18, 1.62 | .27 | |||||||||||||||

| Incomea | 1.02 | 0.65, 1.59 | .93 | |||||||||||||||

| Private insurance (REF: No) | 0.75 | 0.26, 2.22 | .61 | |||||||||||||||

| RURALITY (REF: RUCC 1-3) | 1.45 | 0.53, 3.98 | .47 | |||||||||||||||

| CANCER-RELATED FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Breast Cancer (REF: No) | 1.64 | 0.47, 5.70 | .44 | |||||||||||||||

| Treatment-related symptomsa | 4.03 | 1.69, 9.64 | .002 | |||||||||||||||

| Time since last treatment (REF: <5 years) | 0.24 | 0.07, 0.80 | .02 | |||||||||||||||

| OTHER HEALTH FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tobacco Use (REF: No) | 1.71 | 0.40, 7.37 | .47 | |||||||||||||||

| Number of lifetime comorbiditiesa | 1.14 | 0.98, 1.32 | .09 | |||||||||||||||

| Models with Imputed Data among Wave 1 participants only (n = 81) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Model Fit | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value |

| -- | -- | -- | 5.20 | 2 | .07 | 2.19 | 3 | .53 | 1.52 | 1 | .22 | 21.35 | 3 | .01 | 4.53 | 2 | .10 | |

| Individual Predictors | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Quality of patient-provider communication | 1.65 | 0.57, 4.77 | .35 | 1.49 | 0.49, 4.54 | .48 | 1.48 | 0.49, 4.51 | .49 | 1.89 | 0.63, 5.68 | .25 | 2.19 | 0.62, 7.78 | .23 | 1.99 | 0.65, 6.09 | .23 |

| Written communication | 3.29 | 1.15, 9.46 | .03 | 4.48 | 1.43, 14.02 | .01 | 3.99 | 1.29, 12.38 | .02 | 3.09 | 1.06, 9.02 | .04 | 3.12 | 0.92, 10.62 | .07 | 4.04 | 1.32, 12.36 | .01 |

| DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.96 | 0.92, 1.00 | .06 | |||||||||||||||

| Marital Status (REF: Not Married) | 2.14 | 0.72, 6.41 | .17 | |||||||||||||||

| SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Education (REF: <Bachelor’s) | 0.49 | 0.17, 1.39 | .18 | |||||||||||||||

| Incomea | 1.09 | 0.73, 1.62 | .69 | |||||||||||||||

| Private insurance (REF: No) | 0.72 | 0.26, 2.06 | .54 | |||||||||||||||

| RURALITY (REF: RUCC 1-3) | 1.83 | 0.69, 4.84 | .22 | |||||||||||||||

| CANCER-RELATED FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Breast Cancer (REF: No) | 0.72 | 0.22, 2.32 | .58 | |||||||||||||||

| Treatment-related symptomsa | 3.67 | 1.48, 9.13 | .005 | |||||||||||||||

| Time since last treatment (REF: <5 years) | 0.32 | 0.10, 0.97 | .05 | |||||||||||||||

| OTHER HEALTH FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tobacco Use (REF: No) | 1.86 | 0.36, 9.63 | .46 | |||||||||||||||

| Number of lifetime comorbiditiesa | 1.15 | 0.99, 1.33 | .06 | |||||||||||||||

| Models with Imputed Data among participants in non-metropolitan counties (RUCC 4-9) only (n=53) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Model Fit | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value | LR | df | P value |

| -- | -- | -- | 3.15 | 2 | .21 | 4.46 | 3 | .22 | 3.87 | 1 | .05 | 12.52 | 3 | .04 | 6.24 | 2 | .04 | |

| Individual Predictors | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Quality of patient-provider communication | 3.72 | 0.80, 17.36 | .09 | 2.39 | 0.47, 12.18 | .29 | 2.63 | 0.49, 14.04 | .26 | 5.37 | 1.01, 28.47 | .05 | 3.46 | 0.60, 20.13 | .17 | 7.34 | 1.15, 47.04 | .04 |

| Written communication | 7.72 | 1.79, 33.24 | .01 | 13.8 | 2.53, 75.69 | 0 | 12.6 | 2.23, 71.52 | .004 | 6.08 | 1.33, 27.81 | .02 | 11.61 | 2.20, 61.39 | .004 | 9.73 | 1.94, 48.89 | .006 |

| DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.95 | 0.89, 1.01 | .12 | |||||||||||||||

| Marital Status (REF: Not Married) | 1.78 | 0.40, 7.98 | .45 | |||||||||||||||

| SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Education (REF: <Bachelor’s) | 0.26 | 0.06, 1.24 | .09 | |||||||||||||||

| Incomea | 1.06 | 0.61, 1.85 | .84 | |||||||||||||||

| Private insurance (REF: No) | 0.49 | 0.10, 2.49 | .39 | |||||||||||||||

| RURALITY (continuous) | 1.75 | 0.98, 3.14 | .06 | |||||||||||||||

| CANCER-RELATED FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Breast Cancer (REF: No) | 1.53 | 0.30, 7.92 | .61 | |||||||||||||||

| Treatment-related symptomsa | 3.34 | 1.09, 10.28 | .04 | |||||||||||||||

| Time since last treatment (REF: <5 years) | 0.41 | 0.08, 2.05 | .28 | |||||||||||||||

| OTHER HEALTH FACTORS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tobacco Use (REF: No) | 2.28 | 0.29, 18.07 | .43 | |||||||||||||||

| Number of lifetime comorbiditiesa | 1.28 | 1.02, 1.60 | .03 | |||||||||||||||

Analyzed as a continuous variable.

Significant associations (P < .05) are in bold. Non-significant associations (P < .10) are italicized.

Discussion

There are multiple factors that impact cancer survivorship among rural cancer survivors. Our study is the first to investigate the quality and method of delivery of posttreatment patient-provider communication for self-identified rural cancer survivors. Insights from this rural cancer survivor sample offer an important and underrepresented perspective on posttreatment survivorship care that is critical to timely follow-up care and improving survivorship outcomes. Our study sample and design are also unique in that the aim is to describe multiple posttreatment experiences from a statewide sample of residents that self-identify as rural dwellers representing different cancer types.

Findings from our study underscore the need for communication tools that guide providers through an additional assessment of necessary psychosocial and health behavior supportive care needs of patients completing treatment. Survivorship care needs associated with side effects, self-care, and emotional coping are the highest reported unmet care needs.33 Further, survivorship care needs of rural survivors can differ from the needs of their urban counterparts. Rural cancer survivors experience a greater need for physical and daily living care needs that may be associated with limited access to resources.34 Adequate review and delivery of care needs can improve a survivor’s quality of life,3, 35 satisfaction of care,3 follow-up care initiation and adherence, and other related survivorship outcomes.

Notably, our study highlighted sociodemographic differences in receipt of high-quality patient-provider communication. The findings that survivors with lower levels of education and income were more likely to report a high quality of patient-provider communication were unexpected findings of this study. Higher cancer disease and mortality burdens are associated with low income, low levels of education, and reduced access to quality health care services.36–39 Further, patients living in low socioeconomic conditions more often report poorer communication with their providers.40,41 In a sample of childhood cancer survivors, survivors with an annual household income less than $50,000 were less likely to report any communication focused on survivorship or follow-up screening recommendations.42 One explanation for our findings may have been the lack of convenience-based sampling and the oversampling of female survivors, who when compared to men, are more likely to report poor patient-provider communication.43 Future observational research should incorporate participants’ potential exposure to health equity interventions and programs.

Additionally, respondents who reported receiving written posttreatment communication were 4-5 times more likely than those who received only oral communication to have timely follow-up care. This finding supports the U.S. National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship’s and the CoC’s recommendation that survivors and caregivers should receive a written care plan at diagnosis and throughout survivorship.25 Consistent with this study’s findings, previous studies have reported that written posttreatment survivorship care contributed to the understanding of—and adherence to—necessary follow-up care for cancer survivors.44 However, Kadan-Lottick and associates45 reported that cancer survivors receiving a written survival care plan and verbal communication from a primary care provider were significantly less likely to adhere to recommended follow-up care than those receiving only verbal communication from a provider. A potential explanation for the mixed results on the value of written communication to follow-up care adherence is that providers and survivors report important barriers to fully implementing a written care plan.46,47 The consequences of inconsistent implementation of written posttreatment patient-provider communication can potentially increase measurement errors and limits the interpretation of the findings. Emerging investigations should continue to identify the most functional elements of care plans for providers to initiate posttreatment communication to minimize patient information burden and provider administrative duties.47

There are many challenges associated with recruiting a substantial, diverse, representative sample of exclusively rural respondents. Our study offers an important set of “lessons learned” for obtaining in-depth data from rural cancer survivors, especially regarding data not routinely collected in public health surveillance systems. First, we considered sample size, which was limited in part by distance between the primary study institution and identifying eligible respondents from remote locations as well as available funding. We were unable to access infrastructure for population-based sampling (eg, registry-academic partnerships). We attempted to approach both community and clinical partners for recruitment assistance in Wave 1, using best practices and multiple methods. Yet, recruitment was challenging. It is important to note that remote engagement of largely non-compensated research staff and non-compensated local recruitment partners likely limited our reach to partners that had access to available recruitment resources. During Wave 2, we attempted to use commercial phone lists with a focus on more diverse rural counties. Yet, this strategy did not yield a greater recruitment rate, likely in part due to its broad reach and our inability to obtain an exclusive list of cancer survivors and caregivers. Second, we considered the sampling frame’s ethnic diversity. We had a small, largely white and female sample despite multi-pronged methods and intentional attempts to recruit a diverse sample (eg, tailored flyers throughout Waves 1 and 2, with a Wave 2 focus on more ethnically diverse counties). As well, our sampling frame was not very diverse in general. According to available race/ethnicity data by Illinois county from the 2016-2017 US Census Data, counties represented in this study are 91% Caucasian, 7.5% African American, 1.4% Asian or Pacific Islander, 0.1% Other, and 2.4% Hispanic/Latino.48 Third, we considered that the study team was affiliated with and working from Chicago, Illinois. Consequently, our combined recruitment efforts of engaging non-compensated community and clinical partners remotely, use of predominantly online data collection methods, the use of commercial telephone lists, reliance on materials solely printed in English, and recruitment in predominantly non-Latino white rural settings may not have been optimal for obtaining a diverse sample. Fourth, we considered the representativeness of this sample. Given that 81 respondents of this sample were recruited in Wave 1, our associations likely reflect the experiences of survivors recruited from Wave 1 strategies. This high survey completion rate (99%) likely reflects that this sample may not be representative of all cancer survivors, but represents the experiences of particularly motivated, well-resourced, and higher health literacy rural cancer survivors. Although the generalizability of this study is limited by the small sample size and small representation of individuals from racially/ethnically diverse subpopulations, the implications of these findings are still important to the broader topic of survivorship care planning and its relationship with healthy survivorship outcomes. Further, our study suggests the importance of prioritized funding for rural cancer research and the benefits of recent commitments the National Cancer Institute has made to address this need.49,50

There are several other limitations in this study. Whereas respondents provided retrospective accounts of their patient-provider communication, these findings are subject to recall bias. Consequently, the main study findings focus on the receipt of any written communication, including an SCP or related posttreatment materials; therefore, we used trained interviewers and a broad research question to improve respondent understanding. Yet, it is important for future research to focus on the type of written communication and type of provider who delivers these services (eg, primary care provider, oncologist, or nurse). Additionally, guidelines for recommended follow-up care differ by cancer types. The quality of evidence supporting timely follow-up for cancer recurrence is low, although evidence suggests that longer wait times to follow-up increase the risk of poorer survivorship outcomes.51 Due to this study’s use of a conservative 3-month threshold for timely follow-up care, conclusions may have underreported the frequency of timely follow-up care. Our inferential models were not likely powered to assess the contributing roles of all covariates, especially with regard to participants living in counties with RUCC of 4+. There is a possibility of overestimation, or Type 1 error, for some of our models and we were unable to conduct a full model due to statistical power issues. Relatedly, we were unable to incorporate other important potential confounders, including disease severity (eg, subtype, tumor aggressiveness), type of treatment, and distance from the treatment facility, which were not collected for the parent study. Regarding missingness, although 7% of the surveys were missing annual income data, we observed no difference in the effect of income on the primary association in both the imputed and non-imputed models. Last, information from our findings includes data from rural residents and residents of metropolitan counties (37%) with populations less than 250,000. In spite of the categorization of metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties, all respondents self-identified as rural residents. The nominal designation of rural and urban areas continues to be a point of inquiry through cancer disparities research, and findings from this study add to the prevailing commentary and research to identify the most accurate representation of rural and urban areas as both continuous and discrete groups.49 Finally, the parent study recruited the perspectives of caregivers. However, in this study, dyads were not recruited and caregivers were not asked about patients’ posttreatment follow-up care. Thus, their valuable perspectives could not be incorporated into this study’s analyses. This is an important point for future research, as caregivers’ perspectives and roles may shed light into our study’s results regarding the value of survivors receiving written care plans.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides novel information about the sociodemographic and health care predictors of high-quality posttreatment patient-provider communication and timely follow-up care, and the association between high-quality patient-provider communication and timely follow-up care for rural cancer survivors. The evidence supporting the relationship between timely survivorship follow-up care and survivorship outcomes is limited, and it is imperative to understand posttreatment patient-provider communication for medically underrepresented populations such as rural cancer survivors. This study also provides clear rationale for the need for additional research that can examine effective health communication between patients and providers to ensure uptake of evidence-based recommendations for cancer survivors. In order to standardized communication regarding survivorship care, there is great promise for innovative health communication tools to improve patient-provider communication and explore survivorship communication needs of rural cancer survivors. As cancer survivors are living longer posttreatment and investigations on survivorship care emerge, the current study uniquely contributes to the growing body of evidence that supports the addition of written communication in posttreatment patient-provider communication to improve timely follow-up care.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was an intramurally funded project supported by the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Center for Research on Women and Gender and University of Illinois Cancer Center. Dr. Lewis-Thames was supported by a T32CA190194 (PI: Colditz/James) and by the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital and by Siteman Cancer Center. Ms. Carnahan and Dr. Molina were supported by the Center for Research on Women and Gender and University of Illinois Cancer Center. Drs. Watson and Molina were supported by the UICC. Dr. Molina was supported by the National Cancer Institute (K01CA193918). Dr. James was supported by Siteman Cancer Center and the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and Dr. Watson was also supported by the National Cancer Institute U54CA202997 (Winn MPI) and U54MD012523(Winn/Contact, Ramirez-Valles, Daviglus). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest and no financial disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence Trajectories and Comorbidity Burden among Older Cancer Survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(7):1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66(4):271–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreno PI, Ramirez AG, San Miguel-Majors SL, et al. Unmet supportive care needs in Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors: prevalence and associations with patient-provider communication, satisfaction with cancer care, and symptom burden. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(4):1383–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan A, Gan YX, Oh SK, et al. A culturally adapted survivorship programme for Asian early stage breast cancer patients in Singapore: A randomized, controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2017;26(10):1654–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratjen I, Schafmayer C, Enderle J, et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of colorectal cancer and its association with all-cause mortality: a German cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh-Carlson S, Wong F, Oshan G. Evaluation of the delivery of survivorship care plans for South Asian female breast cancer survivors residing in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2018;25(4):e265–e274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaupin LK, Uwazurike OC, Hydeman JA. A Roadmap to Survivorship: Optimizing Survivorship Care Plans for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutledge TL, Kano M, Guest D, Sussman A, Kinney AY. Optimizing endometrial cancer follow-up and survivorship care for rural and other underserved women: Patient and provider perspectives. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(2):334–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeGuzman P, Colliton K, Nail CJ, Keim-Malpass J. Survivorship Care Plans: Rural, Low-Income Breast Cancer Survivor Perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(6):692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke NJ, Napoles TM, Banks PJ, Orenstein FS, Luce JA, Joseph G. Survivorship Care Plan Information Needs: Perspectives of Safety-Net Breast Cancer Patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forsythe LP, Parry C, Alfano CM, et al. Use of survivorship care plans in the United States: associations with survivorship care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(20):1579–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foa C, Copelli P, Cornelli MC, et al. Meeting the needs of cancer patients: identifying patients’, relatives’ and professionals’ representations. Acta Biomed. 2014;85(3):41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birken SA, Mayer DK, Weiner BJ. Survivorship care plans: prevalence and barriers to use. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):290–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isaacson MJ, Hulme PA, Cowan J, Kerkvliet J. Cancer survivorship care plans: Processes, effective strategies, and challenges in a Northern Plains rural state. Public Health Nurs. 2018;35(4):291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Thomas CC, Massetti GM, Peaker B, Richardson LC. Invasive Cancer Incidence, 2004-2013, and Deaths, 2006-2015, in Nonmetropolitan and Metropolitan Counties - United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(14):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, Srinivasan S, Croyle RT. Making the Case for Investment in Rural Cancer Control: An Analysis of Rural Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Funding Trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(7):992–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell TC, Dilley SE, Bae S, Straughn JM Jr., Kim KH, Leath CA 3rd. The Impact of Racial, Geographic, and Socioeconomic Risk Factors on the Development of Advanced-Stage Cervical Cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2018;22(4):269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDougall JA, Banegas MP, Wiggins CL, Chiu VK, Rajput A, Kinney AY. Rural Disparities in Treatment-Related Financial Hardship and Adherence to Surveillance Colonoscopy in Diverse Colorectal Cancer Survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(11):1275–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karst JS, Hoag JA, Chan SF, et al. Assessment of end-of-treatment transition needs for pediatric cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients and their families. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(8):e27109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, Harvey C. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2270–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carcaise-Edinboro P, Bradley CJ. Influence of patient-provider communication on colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2008;46(7):738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz MH. Future of the safety net under health reform. Jama. 2010;304(6):679–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalton AF, Bunton AJ, Cykert S, et al. Patient characteristics associated with favorable perceptions of patient-provider communication in early-stage lung cancer treatment. J Health Commun. 2014;19(5):532–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States Department of Agriculture. Rural Urban Continuum Codes https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/, 2019.

- 25.National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS). Journey Forward http://www.canceradvocacy.org/partnerships/journeyforward, 2019.

- 26.Yabroff KR, Dowling E, Rodriguez J, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) experiences with cancer survivorship supplement. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2012;6(4):407–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gold HT, Do HT, Dick AW. Correlates and effect of suboptimal radiotherapy in women with ductal carcinoma in situ or early invasive breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3108–3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hershman DL, Wang X, McBride R, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Delay of adjuvant chemotherapy initiation following breast cancer surgery among elderly women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99(3):313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeffery M, Hickey BE, Hider PN, See AM. Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:Cd002200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey data. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/list.asp?cat=OH&yr-2008&qkey=6610&state=All 2008.

- 31.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30a(9):1326–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(2):156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Rooij BH, Park ER, Perez GK, et al. Cluster Analysis Demonstrates the Need to Individualize Care for Cancer Survivors. Oncologist. 2018;23(12):1474–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butow PN, Phillips F, Schweder J, White K, Underhill C, Goldstein D. Psychosocial well-being and supportive care needs of cancer patients living in urban and rural/regional areas: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(1):1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jansen F, Eerenstein SEJ, Lissenberg-Witte BI, van Uden-Kraan CF, Leemans CRJ, Leeuw IMV. Unmet supportive care needs in patients treated with total laryngectomy and its associated factors. Head Neck. 2018;40(12):2633–2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh GK, Williams SD, Siahpush M, Mulhollen A. Socioeconomic, rural-urban, and racial inequalities in US cancer mortality: Part I—All cancers and lung cancer and Part II—Colorectal, prostate, breast, and cervical cancers. Journal of cancer epidemiology. 2012;2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh GK. Rural-urban trends and patterns in cervical cancer mortality, incidence, stage, and survival in the United States, 1950-2008. J Community Health. 2012;37(1):217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Edwards BK. Area socioeconomic variations in US cancer incidence, mortality, stage, treatment, and survival, 1975-1999. NCI cancer surveillance monograph series. 2003;4. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Feuer EJ, Pickle LW. Changing area socioeconomic patterns in U.S. cancer mortality, 1950-1998: Part I--All cancers among men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(12):904–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caplin DA, Smith KR, Ness KK, et al. Effect of Population Socioeconomic and Health System Factors on Medical Care of Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(1):74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okunrintemi V, Khera R, Spatz ES, et al. Association of Income Disparities with Patient-Reported Healthcare Experience. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4401–4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okunrintemi V, Valero-Elizondo J, Patrick B, et al. Gender Differences in Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Adults With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24):e010498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Birken SA, Clary AS, Bernstein S, et al. Strategies for Successful Survivorship Care Plan Implementation: Results From a Qualitative Study. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(8):e462–e483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kadan-Lottick NS, Ross WL, Mitchell HR, Rotatori J, Gross CP, Ma X. Randomized Trial of the Impact of Empowering Childhood Cancer Survivors With Survivorship Care Plans. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(12):1352–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, Merrill JK, Wollins DS, Shulman LN. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(6):345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morken CM, Tevaarwerk AJ, Swiecichowski AK, et al. Survivor and Clinician Assessment of Survivorship Care Plans for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Patients: An Engineering, Primary Care, and Oncology Collaborative for Survivorship Health. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.U.S. Department of Commerce. 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/navigation/1.0/en/d_dataset:ACS_17_5YR/d_product_type:DATA_PROFILE/, 2019.

- 49.Yaghjyan L, Cogle CR, Deng G, et al. Continuous Rural-Urban Coding for Cancer Disparity Studies: Is It Appropriate for Statistical Analysis? International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019;16(6):1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martínez ME, Paskett ED. Using the Cancer Moonshot to Conquer Cancer Disparities: A Model for Action. JAMA oncology. 2018;4(5):624–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doubeni CA, Gabler NB, Wheeler CM, et al. Timely follow-up of positive cancer screening results: A systematic review and recommendations from the PROSPR Consortium. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(3):199–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]