Abstract

Background

Persons with severe, persistent mental illness (SPMI) are at high risk for poor health and premature mortality. Integrating primary care in a mental health center may improve health outcomes in a population with SPMI in a socioeconomically distressed region of the USA.

Objective

To examine the effects of reverse colocated integrated care on persons with SPMI and co-morbid chronic disease receiving behavioral health services at a local mental health authority located at the US–Mexico border.

Design

Randomized trial evaluating the effect of a reverse colocated integrated care intervention among chronically ill adults.

Participants

Participants were recruited at a clinic between November 24, 2015, and June 30, 2016.

Interventions

Receipt of at least two visits with a primary care provider and at least one visit with a chronic care nurse or dietician, compared with usual care (behavioral health only).

Main Measures

The primary outcome was blood pressure. Secondary outcomes included HbA1c, BMI, total cholesterol, and depressive symptoms. Sociodemographic data were collected at baseline, and outcomes were measured at baseline and 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

Key Results

A total of 416 participants were randomized to the intervention (n = 249) or usual care (n = 167). Groups were well balanced on almost all baseline characteristics. At 12 months, intent-to-treat analysis showed intervention participants improved their systolic blood pressure (β = − 3.86, p = 0.04) and HbA1c (β = − 0.36, p = 0.001) compared with usual care participants when controlling for age, sex, and other baseline characteristics. No participants withdrew from the study due to adverse effects. Per-protocol analyses yielded similar results to intent-to-treat analyses and found a significantly protective effect on diastolic blood pressure. Older and diabetic populations differentially benefited from this intervention.

Conclusions

Colocation and integration of behavioral health and primary care improved blood pressure and HbA1c after 1-year follow-up for persons with SPMI and co-morbid chronic disease in a US–Mexico border community.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov, Identifier: NCT03881657

KEY WORDS: mental illness, primary care, integrated care, blood pressure, diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Persons with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI)—including schizophrenia, psychotic disorders, and mood disorders such as major depression and bipolar disorders—experience excessive morbidity and mortality.1 The average life span of a person with SPMI is 1 to 10 years shorter than that of persons without SPMI,2 a consistent disparity in premature death in the USA for decades.3–5 Persons with SPMI have a high prevalence of preventable morbidity, including cardiovascular disease,6 diabetes,7 respiratory disease,8 and infectious disease.9, 10 Due to complexities of their mental illness and poor health, persons with SPMI have high utilization rates of episodic and emergency medical services11 leading to higher medical costs.12, 13

Literature shows racial and ethnic minority groups with mental illness are vulnerable to additional health risks. Hispanics with SPMI experience elevated rates of chronic disease and metabolic syndrome.14, 15 They are also more likely to face barriers accessing primary and behavioral health care due to socioeconomic and societal factors including limited English proficiency, cultural barriers, stigma, and discrimination.14

Integrated care is an innovative strategy with a growing body of evidence demonstrating effectiveness in improving health care access and outcomes for SPMI populations.16–20 Reverse colocation—that is, physically locating primary care within behavioral health settings—has been shown to improve routine primary care access for persons with SPMI.16 Reverse colocation of primary care may be convenient and cost-effective,16, 18, 19 as it locates care within settings persons with SPMI may see as trusted, but physical colocation alone may be insufficient to improve health.21 Collaborative, integrated, colocated care is necessary to improve outcomes for persons with SPMI.16, 21, 22

Little evidence exists regarding impact of reverse colocated integrated care on health outcomes in an SPMI population. There is no prior trial of reverse integrated care approaches in predominantly Hispanic US–Mexico border communities. This may be the result of trial recruitment and retention challenges in persons with SPMI.23 The sociopolitical environment at the US–Mexico border presents challenges for residents who may mistrust health care due to perceived discrimination toward minorities and immigrants.24, 25

This is the first randomized control trial (RCT) of reverse colocated integrated care conducted in a local mental health authority setting in a predominantly Hispanic population within a socioeconomically distressed area at the US–Mexico border. We hypothesize reverse colocated integrated care will reduce blood pressure, total cholesterol, HbA1c, body mass index, and depressive symptoms among persons with SPMI and chronic disease.

METHODS

Study Design

The study was conducted at the Brownsville clinic of Tropical Texas Behavioral Health (TTBH) in Southern Texas. The RCT compared intervention participants receiving integrated care with controls receiving usual care provided within a behavioral health clinic for patients with SPMI. Participants were followed for 12 months with baseline and 6-month (midpoint) and 12-month (endpoint) follow-ups.

Study Participants

Adult patients receiving care at TTBH were eligible for the study if they had a diagnosis of hypertension, obesity, poorly controlled diabetes, and/or hypercholesterolemia and self-reported no source of primary care. All TTBH patients are screened for chronic disease upon intake. Eligible study participants had one or more SPMI diagnoses, were eligible to receive behavioral health services at TTBH, and resided in Cameron, Hidalgo, or Willacy counties. To be a TTBH patient, an individual must have a psychiatrist assessment and be diagnosed with a mental health diagnosis, i.e., bipolar, schizophrenia, depression, or a combination of these diagnoses. Self-reported pregnant patients were ineligible for participation. Potentially eligible participants were not approached if they had suicide ideation at the time of recruitment. We estimated an effective sample size of 145 per study group, powered at 80%.26

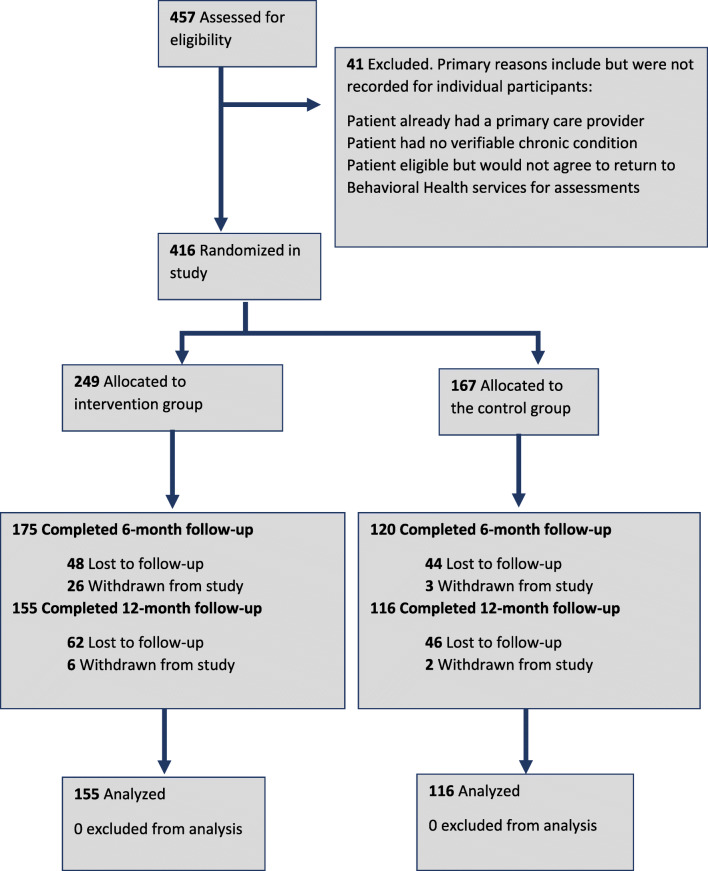

TTBH patients were pre-screened for eligibility through electronic medical record (EMR) review, and individuals meeting the preliminary criteria scheduled for upcoming behavioral health appointments at the clinic were mailed study recruitment letters and approached in-person on appointment days. Behavioral health staff referred potential participants to study staff, and posters and brochures were displayed in waiting rooms. Interested participants were re-screened for eligibility by a behavioral health care assistant. All participants who met eligibility requirements and agreed to participate went through an informed consent process26 modified from the Dunn et al. process for persons with schizophrenia.27 A total of 457 TTBH patients were assessed for eligibility, and 41 patients were excluded for ineligibility or chose not to enroll (Fig. 1). Some patients were ineligible because they reported having a primary care provider or had no verifiable chronic condition. Other eligible patients did not agree to return for assessments.]-->

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram, Tropical Texas Behavioral Health Integrated Care Trial.

Participants received a gift card upon completion of each assessment: $10 at baseline, $20 at midpoint, and $30 at endpoint. New England Independent Review Board approved the research protocol (Protocol ID no. 120160441). No methodological changes were made after trial initiation.

Randomization and Baseline Assessment

Participants were allocated to group (allocation ratio 1:1) using simple randomization. Group assignment was based on an Excel-generated number and randomly selected by the participant from a box. Once randomly assigned to the intervention or control group, participant sociodemographic data (age, sex, ethnicity, education, primary language spoken) and SPMI diagnoses were collected from the clinic EMR. Baseline health outcome measures were collected through assessment of vital signs, blood tests, and provider-administered behavioral health assessments. To address the ethical issue of primary care access in the usual care group, TTBH assigned a care coordinator to help control group participants connect to community-based care.28

Integrated Care Intervention

Full details of the study protocol are published elsewhere.26 The clinic developed an integrated care model based on the Wagner model for effective chronic illness care featuring a delivery system linked with complementary treatment and services, sustained by productive and synergistic interactions between multidisciplinary care teams and patients.29 TTBH’s theory of change was colocated, integrated, bilingual services provided by a multidisciplinary team embedded in an institution perceived as safe and trusted by patients with mental illness would increase primary care access and patient treatment compliance leading to improved health. TTBH implemented integrated care team meetings and utilized electronic communication through their EMR.

Patients randomized to the intervention group were initially seen at the TTBH program for physical assessment. The program provider treated participants’ chronic conditions at their discretion and referred patients to the care coordinator and chronic care nurse or registered dietician as appropriate within 7 days of the initial visit. A care coordinator made a follow-up appointment for the patient. This process was repeated at every visit.

Usual Care

TTBH usual care consists of behavioral health services without primary care. This includes case management, behavioral health services, and a drop-in center. Controls were referred to the nearest federally qualified health center (FQHC) or health department. Each control was assigned a behavioral health case manager who referred them to external primary care services. Systematic tracking of referrals to external primary care was not feasible.

Outcome Measures

Blood pressure was the primary outcome, measured by the primary care provider manually using a manometer.30 TTBH chose blood pressure as the primary outcome because of prior research identifying hypertension as susceptible to improvement.6 Secondary outcomes included HbA1c, body mass index (BMI), total cholesterol, and depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score).31 The PHQ-9 assessment was administered to participants via provider interview. HbA1c was measured for all participants per TTBH’s universal HbA1c screening policy. BMI was calculated using a clinical weight scale and height measurement instrument.32 Total cholesterol was measured via blood test.

Covariates and Effect Modifiers

Other participant sociodemographic factors and morbidities included age, sex, ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic other), education (below high school, high school, or higher), language (English, Spanish), and baseline physical and mental health conditions. Age was categorized: 18–24; 25–34; 35–44; 45–54; 55–64; and ≥ 65 years. Due to the sample being predominantly Hispanic, a dichotomous ethnicity variable (Hispanic, non-Hispanic) was used. The Adult Needs and Strengths Assessment was used to assess functioning and quality of life.26, 33 We examined age as a potential modifier of treatment effect on diabetes.34 Age was dichotomized based on mean age (40 years).

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis was an intent-to-treat analysis of the differences in health outcomes (primary: blood pressure; secondary: HbA1c, BMI, total cholesterol, and depressive symptoms) between intervention and control participants at endpoint. Baseline equivalence of the study groups on covariates and outcome variables was analyzed by the Pearson Chi-square test for categorical variables and two-sample t test for continuous variables, using 2-sided statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level. We conducted unadjusted between-group differences in 12-month health outcomes, and bivariate analyses to understand within-group differences between baseline and 12-month outcomes by group assignment.

To control for important covariates (e.g., age, sex) and potential confounders identified in bivariate analyses, we conducted an endpoint analysis of the 12-month follow-up outcomes accounting for baseline measures different between groups, using multivariable linear regression analysis with the identity link function.35, 36 We developed models adjusted by different variables for each outcome based on clinical relevance or literature. A backward elimination model selection procedure was used for parsimony; covariates were removed from the model if their p values were greater than 0.15; age, sex, and baseline outcome values were included in all models a priori.37 Additionally, we adjusted blood pressure and PHQ-9 models with the number of baseline comorbidities; diastolic blood pressure with ethnicity; and PHQ-9 with major depression status and ANSA score.

We examined variance inflation factors in the adjusted models, and the variance inflation factors for the predictors were all below 2, suggesting no evidence of collinearity in the regression model.38 We reported beta coefficients for continuous outcomes. We conducted a per-protocol analysis using actual receipt of the minimum intervention dose. To assess effect modification, we evaluated the interaction terms between intervention status and the potential effect modifier. We performed stratified analyses where significant interaction terms were detected. Missing data among all covariates was minimal (< 1% per covariate) due to data collection protocol adherence. We applied multiple imputation to assess treatment effect for PHQ-9, accounting for 24% missing data at endpoint due to random loss to follow-up. We conducted analyses with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.). Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Enrollment, Follow-up, and Attrition

Participants were recruited between November 24, 2015, and June 30, 2016, and follow-up ended on August 22, 2017. Of 457 eligible patients, 416 were recruited and randomized into the control (n = 167) or intervention (n = 249) groups. There are more intervention participants than control because TTBH anticipated larger enrollment and generated more numbers than used. Of these patients, 295 (71%) completed the 6-month follow-up and 271 (65%) completed 12-month follow-up. Qualifying baseline SPMI diagnoses included major depression (45.0%), bipolar disorder (31.3%), schizophrenia (21.3%), or a dual diagnosis of schizophrenia and major depression (2.4%). The intervention group reached its target (n = 182), but attrition for both groups was larger than anticipated (65% actual vs. 80% planned). Retention rates did not differ by group (62% intervention vs. 69% control, p = 0.13). No harm or unintended effects to participants were observed.

Baseline Participant Characteristics

No statistically significant baseline differences were observed between groups for sociodemographic measures or health outcomes except systolic blood pressure (Table 1). Controls had a significantly higher mean systolic blood pressure (129.6 mmHg) than the intervention group (125.6 mmHg) at baseline (p = 0.03).

Table 1.

Study Participant Characteristics at Baseline by Intervention Group, Tropical Texas Behavioral Health Integrated Care Trial

| Intervention (n = 249) (N (%)) |

Control (n = 167) (N (%)) |

p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 137 (55.0) | 93 (55.7) | 0.89 |

| Hispanic | 226 (90.8) | 159 (95.2) | 0.21 |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 41.0 (12.5) | 40.7 (13.4) | 0.82 |

| 18–24 | 30 (12.0) | 18 (10.8) | 0.27 |

| 25–34 | 49 (19.7) | 45 (26.9) | |

| 35–44 | 69 (27.7) | 43 (25.7) | |

| 45–54 | 61 (24.5) | 34 (20.4) | |

| 55–64 | 35 (14.1) | 19 (11.4) | |

| 65+ | 5 (2.0) | 8 (4.8) | |

| Education | |||

| Below high school | 143 (59.1) | 97 (59.9) | 0.87 |

| High school or higher | 99 (40.9) | 65 (40.1) | |

| Missing | 7 | 5 | |

| Primary language spoken | |||

| English | 173 (69.8) | 111 (66.5) | 0.71 |

| Spanish | 75 (30.2) | 56 (33.5) | |

| Missing | 1 | – | |

| SPMI diagnosis | |||

| Bipolar disorder | 78 (31.3) | 51 (30.5) | 0.30 |

| Major depression | 112 (45.0) | 79 (47.3) | |

| Schizophrenia | 53 (21.3) | 28 (16.8) | |

| Schizophrenia and major depression | 6 (2.4) | 9 (5.4) | |

| Health outcomes (mean (SD)) | |||

| Systolic blood pressure | 125.6 (18.6) | 129.6 (17.5) | 0.03 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 78.8 (10.2) | 79.3 (10.4) | 0.60 |

| HbA1c | 6.1 (1.3) | 6.3 (1.9) | 0.11 |

| BMI | 33.7 (7.6) | 34.0 (9.3) | 0.71 |

| Total cholesterol | 188.5 (46.1) | 184.9 (42.9) | 0.43 |

| PHQ-9 | 11.4 (6.4) | 12.2 (7.0) | 0.26 |

| ANSA | 2.0 (2.4) | 2.0 (2.1) | 0.81 |

*Italics denotes statistical significance (p value <0.05)

Twelve-Month Outcomes

Intervention participation was associated with improved systolic blood pressure and HbA1c (Table 2). On average, intervention participants had significantly lower systolic blood pressure than controls (adjusted mean difference = − 3.86, p = 0.04). The intervention group had a lower average HbA1c compared with the control group at the end of the study (adjusted mean difference = − 0.36, p = 0.001). Differences were observed in diastolic blood pressure and BMI trended in the anticipated direction but were not significant. The intervention was not found to significantly impact total cholesterol or depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Effect of IBH Intervention on Health Outcomes at 12 Months, Tropical Texas Behavioral Health Integrated Care Trial

| n | Intervention mean (SD) | Control mean (SD) | Intervention–control adjusted mean difference (SE) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure | 261 | 117.3 (17.7) | 120.3 (17.5) | − 3.86 (1.89)† | 0.04 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 261 | 73.4 (10.9) | 74.6 (10.5) | − 2.05 (1.15)‡ | 0.08 |

| HbA1c | 261 | 5.9 (1.0) | 6.2 (1.8) | − 0.36 (0.11)§ | 0.001 |

| BMI | 261 | 34.1 (8.2) | 34.2 (9.7) | 0.70 (0.36)ǁ | 0.05 |

| Cholesterol | 261 | 187.1 (39.4) | 186.6 (42.2) | − 1.36 (3.99)¶ | 0.73 |

| PHQ-9 | 271 | 9.5 (5.9) | 9.6 (5.8) | − 0.39 (0.75)# | 0.60 |

*Italics denotes statistical significance (p value < 0.05); all regression analyses adjusted for age and sex

†Additional adjustment for baseline blood pressure and number of comorbidities at baseline

‡Additional adjustment for ethnicity, baseline diastolic blood pressure, and number of comorbidities at baseline

§Additional adjustment for baseline HbA1c

ǁAdditional adjustment for baseline BMI

¶Additional adjustment for baseline total cholesterol

#Additional adjustment for major depression, baseline PHQ-9 and ANSA scores, and number of comorbidities at baseline

Effect Modification

We explored modification of intervention effect on HbA1c at endpoint by age based on research indicating HbA1c levels are positively associated with age in non-diabetic populations.34 When examining the possible interaction between age and intervention group within the sample, a significant interaction term was detected in the model for HbA1c level (adjusted mean difference − 0.50, p = 0.03), indicating the effect of the intervention on HbA1c was significantly different for participants under 40 years compared with those 40 years or older. No other outcomes were found to have significant effect modification by age group. In age-group stratified analyses, there was no significant difference in HbA1c between intervention and control groups among individuals younger than 40 years. A significant difference in HbA1c between the intervention and control groups was identified for individuals aged 40 or above (Table 3). Among those 40 years or older, those in the intervention group had, on average, a lower HbA1c than controls (adjusted mean difference − 0.60, p = 0.001).

Table 3.

Effect of IBH on HbA1c at 12 Months, Stratified by Age Groups and by Diabetic Status at Baseline, Tropical Texas Behavioral Health Integrated Care Trial

| Intervention mean (SD) | Control mean (SD) | Intervention–control adjusted mean difference (SE) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Participants 40+ years | 6.1 (1.1) | 6.7 (2.1) | − 0.6 (0.2)† | 0.001 |

| Participants under 40 years | 5.6 (0.7) | 5.7 (1.2) | − 0.1 (0.1)† | 0.25 |

| Diabetic status | ||||

| Diabetic participants | 7.3 (1.3) | 9.0 (2.5) | − 1.9 (0.5)‡ | < 0.001 |

| Non-diabetic participants | 5.6 (0.6) | 5.6 (0.5) | 0.04 (0.1) § | 0.45 |

*Italics denotes statistical significance of p value < 0.05

†Adjusted for sex and baseline HbA1c

‡Adjusted for sex, age, education status, and baseline HbA1c

§Adjusted for sex, age, number of comorbidities at baseline, and baseline HbA1c

There was significant interaction of intervention group and baseline HbA1c level (HbA1c level > 6.5% indicating diabetes compared with HbA1c < 6.5%) when included in the model for 12-month HbA1c (adjusted mean difference − 1.46, p < 0.001). Diabetic intervention participants had a significantly lower HbA1c level at endpoint compared with controls (adjusted mean difference − 1.9, p < 0.001; Table 3). There was no significant interaction between diabetic and intervention status for any other outcome.

Per-Protocol Analysis

For participants who completed an endpoint assessment, 74% of intervention participants received the full intervention (two visits with a primary care provider; one visit with either a registered dietician or chronic care nurse). On average, intervention participants had 12.6 visits with a primary care provider and 6.7 visits with the dietician or chronic care nurse during the study.

We conducted per-protocol analysis to assess whether receiving the full intervention affected health outcomes. When comparing only intervention participants who received the full intervention (n = 115) with controls, significant improvements were detected in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and HbA1c (Table 4). Intervention participants had lower systolic blood pressure (adjusted mean difference − 4.46, p = 0.03) and HbA1c levels (adjusted mean difference − 0.39, p = 0.003) on average compared with controls. Intervention participants had a significantly lower diastolic blood pressure on average than controls (adjusted mean difference − 2.61, p = 0.04).

Table 4.

Effect of IBH Intervention on Health Outcomes at 12 Months, Per-Protocol Analysis, Tropical Texas Behavioral Health Integrated Care Trial

| n | Intervention mean (SD) | Control mean (SD) | Intervention–control adjusted mean difference (SE) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure | 222 | 117.1 (17.8) | 120.3 (17.5) | − 4.46 (2.09)† | 0.03 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 222 | 72.9 (11.0) | 74.6 (10.5) | − 2.61 (1.27)‡ | 0.04 |

| HbA1c | 222 | 6.0 (1.1) | 6.2 (1.8) | − 0.39 (0.13)§ | 0.003 |

| BMI | 222 | 34.7 (8.3) | 34.2 (9.7) | 0.78 (0.40) ǁ | 0.050 |

| Cholesterol | 222 | 187.1 (36.7) | 186.6 (42.2) | − 5.48 (4.17) ¶ | 0.19 |

| PHQ-9 | 231 | 8.9 (5.9) | 9.6 (5.8) | − 0.33 (0.73) # | 0.65 |

*Italics denotes statistical significance of p value < 0.05; all regression analyses adjusted for age and sex

†Additional adjustment for baseline blood pressure and number of comorbidities at baseline

‡Additional adjustment for ethnicity, baseline diastolic blood pressure, and number of comorbidities at baseline

§Additional adjustment for baseline HbA1c

ǁAdditional adjustment for baseline BMI

¶Additional adjustment for ethnicity and baseline total cholesterol

#Adjusted for age, sex, and baseline PHQ-9 and life functioning scores

DISCUSSION

This study found a reverse colocated integrated care approach implemented within a local mental health authority setting compared with behavioral health care alone can improve physical health outcomes in persons with SPMI. The intervention significantly reduced systolic blood pressure and HbA1c within a year in a population known for fragmented health care utilization. It is likely these effects were observed because of effective, available hypertension and diabetes treatment. To the authors’ knowledge, there are no other RCTs that demonstrate an integrated care intervention effect on systolic blood pressure or HbA1c in an SPMI population. The study also demonstrated a full dose of the intervention resulted in increased magnitude of intervention effect on reducing systolic blood pressure and HbA1c and identified a significant intervention effect on reducing diastolic blood pressure. These effects were observed in a population healthier at baseline than one would expect in persons with SPMI. These findings build on a growing body of literature demonstrating efficacy of integrated care in mental health settings.16–20 This study pushes the field forward in demonstrating physical health improvements in a predominantly Hispanic population in a socioeconomically distressed region. The trial was also implemented during a period of significant sociopolitical challenges with the targeted study population under stress related to immigration uncertainty. These conditions represent the real-world circumstances faced by underserved populations under which evidence-based models should be implemented and evaluated to ensure their effectiveness.

While the study demonstrated a significant reduction in HbA1c when comparing the intervention group with controls at endpoint, effect modification assessment revealed stronger intervention effects among participants who were diabetic at baseline and those who were > 40 years old. These results suggest participants with the greatest treatment need experienced greater impacts as a result of the intervention than those with less need. This finding raises the question about what kind of intervention (e.g., screening) would be more effective among non-diabetics or younger populations or if targeting sicker patients with more intensive integrated care would produce greater benefit.

The intervention effect was observed with a participant average of 12.6 primary care visits. It is possible patients utilized a lot of primary care because of it being new or free. It is possible TTBH staff attempted to prevent no-shows by scheduling appointments in concert with monthly behavioral health visits. An implementation study of TTBH’s intervention did not uncover further evidence. High utilization raises questions about feasibility of integrated care in this population.

The study has several limitations. The 12-month retention rate was lower than planned (65% vs. 80%). Although there was no significant difference among observed variables by patients’ attrition status, the study may have been underpowered due to loss to follow-up for examining some outcomes. For example, the magnitude of the intervention effect on patients’ diastolic blood pressure was consistent with our expectations; however, the p value of 0.08 was marginal within our intent-to-treat analysis, masking clear benefit. We had limited patient-level characteristic data and were unable to examine several socioeconomic factors (e.g., income, insurance, employment).16, 18 Mean systolic blood pressure was not equivalent at baseline, raising regression to the mean as a potential issue. Regression to the mean is not likely to have affected findings because of trial rigor and mean systolic blood pressure being higher in controls at baseline. Participants are predominantly Hispanic living in a resource-limited region, which limits generalizability of findings to other populations or settings where there is greater heterogeneity of racial/ethnic groups, with less severe mental health, or in higher resourced areas with better health care access. There is potential for misclassification bias since TTBH did not have the capacity to track external primary care. We are unable to fully compare intervention participants with controls who may have little or no primary care access. Identification of significant differences in blood pressure and HbA1c by treatment status in both intent-to-treat and per-protocol analyses suggests contamination may not bias findings.

This study demonstrates reverse colocated integrated care can improve physical health for SPMI patients with chronic disease, offering avenues to reduce health inequities of persons with SPMI. Local mental health authorities and substance abuse/addiction clinics are attractive settings for additional testing of integrated care. Cost-effectiveness research is needed to assess whether reverse colocation integrated care strategies are financially sustainable in diverse communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff and patients of Tropical Texas Behavioral Health who made this research possible. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Alison El Ayadi for her critical feedback on the draft manuscript.

Funding Information

This research was funded by the Corporation for National and Community Service under Social Innovation Fund Grant Number 14SIHTX001.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carey MP, Carey KB. Behavioral research on severe and persistent mental illnesses. Behav Ther. 1999;30(3):345–353. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(99)80014-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DE Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:502–508. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:11–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott KM, de Jonge P, Alonso J, et al. Associations between DSM-IV mental disorders and subsequent heart disease onset: beyond depression. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(6):5293–5299. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chwastiak LA, Davydow DS, McKibbin CL, et al. The Effect of Serious Mental Illness on the Risk of Rehospitalization Among Patients With Diabetes. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinschmidt KM, Ingram M, Schachter K, Sabo S, Verdugo L, Carvajal S. The Impact of Integrating Community Advocacy Into Community Health Worker Roles on Health-Focused Organizations and Community Health Workers in Southern Arizona. J Ambul Care Manage. 2015;38(3):244–253. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagios K, Deane FP. Severe mental illness is a new risk marker for blood-borne viruses and sexually transmitted infections. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(6):562–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes E, Bassi S, Gilbody S, Bland M, Martin F. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(1):40–48. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00357-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt KA, Weber EJ, Showstack JA, Colby DC, Callaham ML. Characteristics of Frequent Users of Emergency Departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothbard AB, Metraux S, Blank MB. Cost of Care for Medicaid Recipients With Serious Mental Illness and HIV Infection or AIDS. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(9):1240–1246. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.9.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cloutier M, Sanon Aigbogun M, Guerin A, et al. The Economic Burden of Schizophrenia in the United States in 2013. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(06):764–771. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carliner H, Collins PY, Cabassa LJ, McNallen A, Joestl SS, Lewis-Fernández R. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among racial and ethnic minorities with schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders: a critical literature review. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(2):233–247. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellerstein DJ, Almeida G, Devlin MJ, et al. Assessing Obesity and Other Related Health Problems of Mentally Ill Hispanic Patients in an Urban Outpatient Setting. Psychiatr Q. 2007;78(3):171–181. doi: 10.1007/s11126-007-9038-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, Rosenheck RA. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(9):861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, Rask KJ, Zhao L, Parker RM. A Randomized Trial of Medical Care Management for Community Mental Health Settings: The Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):151–159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boardman JB. Health access and integration for adults with serious and persistent mental illness. Fam Syst Heal. 2006;24(1):3–18. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.24.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shackelford JR, Sirna M, Mangurian C, Dilley JW, Shumway M. Descriptive analysis of a novel health care approach: reverse colocation-primary care in a community mental health "home". Prim care companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(5). 10.4088/PCC.13m01530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cabassa LJ, Gomes AP, Meyreles Q, et al. Using the collaborative intervention planning framework to adapt a health-care manager intervention to a new population and provider group to improve the health of people with serious mental illness. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):178. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0178-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodgers M, Dalton J, Harden M, Street A, Parker G, Eastwood A. Integrated care to address the physical health needs of people with severe mental illness: A mapping review of the recent evidence on barriers, facilitators and evaluations. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(1). 10.5334/ijic.2605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bradford DW, Cunningham NT, Slubicki MN, et al. An evidence synthesis of care models to improve general medical outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness: A systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(8). 10.4088/JCP.12r07666 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kanuch SW, Cassidy KA, Dawson NV, Athey M, Fuentes-Casiano E, Sajatovic M. Recruiting and Retaining Individuals with Serious Mental Illness and Diabetes in Clinical Research: Lessons Learned from a Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2016;9(3):115–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berk ML, Schur CL. The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. J Immigr Health. 2001;3(3):151–156. doi: 10.1023/A:1011389105821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Escamilla R, Garcia J, Song D. HEALTH CARE ACCESS AMONG HISPANIC IMMIGRANTS: ¿ALGUIEN ESTÁ ESCUCHANDO? [IS ANYBODY LISTENING?] NAPA Bull. 2010;34(1):47–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4797.2010.01051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sautter Errichetti K, Ramirez MM, Flynn A, Xuan Z. A reverse colocated integrated care model intervention among persons with severe persistent mental illness at the U.S.-Mexico border: A randomized controlled trial protocol. Contemp Clin trials Commun. 2019;16:100490. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunn LB, Lindamer LA, Palmer BW, Golshan S, Schneiderman LJ, Jeste DV. Improving Understanding of Research Consent in Middle-Aged and Elderly Patients With Psychotic Disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(2):142–150. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibbons CJ, Stirman SW, Brown GK, Beck AT. Engagement and retention of suicide attempters in clinical research: challenges and solutions. Crisis. 2010;31(2):62–68. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1(1):2–4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10345255. Accessed May 29, 2019. [PubMed]

- 30.(UK) NCGC. Hypertension. Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22855971. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/J.1525-1497.2001.016009606.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.(UK) NCGC. Obesity. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25535639. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- 33.Nelson C, Johnston M. Adult Needs and Strengths Assessment–Abbreviated Referral Version to Specify Psychiatric Care Needed for Incoming Patients: Exploratory Analysis. Psychol Rep. 2008;102(1):131–143. doi: 10.2466/pr0.102.1.131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pani LN, Korenda L, Meigs JB, et al. Effect of aging on A1C levels in individuals without diabetes: evidence from the Framingham Offspring Study and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2004. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(10):1991–1996. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liebschutz JM, Xuan Z, Shanahan CW, et al. Improving Adherence to Long-term Opioid Therapy Guidelines to Reduce Opioid Misuse in Primary Care. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1265. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lasser KE, Quintiliani LM, Truong V, et al. Effect of Patient Navigation and Financial Incentives on Smoking Cessation Among Primary Care Patients at an Urban Safety-Net Hospital. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1798. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mickey RM, Greenland S. THE IMPACT OF CONFOUNDER SELECTION CRITERIA ON EFFECT ESTIMATION. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125–137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity. New York: Wiley; 1980.