Abstract

Objectives

Visible minorities are a group categorized in health research to identify and track inequalities, or to study the impact of racialization. We compared classifications obtained from a commonly used measure (Statistics Canada standard) with those obtained by two direct questions—whether one is a member of a visible minority group and whether one is perceived or treated as a person of colour.

Methods

A mixed-methods analysis was conducted using data from an English-language online survey (n = 311) and cognitive interviews with a maximum diversity subsample (n = 79). Participants were Canadian residents age 14 and older.

Results

Agreement between the single visible minority item and the standard was good (Cohen’s Κ = 0.725; 95% CI = 0.629, 0.820). However, participants understood “visible minority” in different and often literal ways, sometimes including those living with visible disabilities or who were visibly transgender or poor. Agreement between the single person of colour item and the standard was very good (Κ = 0.830; 95% CI = 0.747, 0.913). “Person of colour” was more clearly understood to reflect ethnoracial background and may better capture the group likely to be targeted for racism than the Statistics Canada standard. When Indigenous participants who reported being persons of colour were reclassified to reflect the government definition of visible minority as non-Indigenous, this measure had strong agreement with the current federal standard measure (K = 0.851; 95% CI = 0.772, 0.930).

Conclusion

A single question on perception or treatment as a person of colour appears to well identify racialized persons and may alternately be recoded to approximate government classification of visible minorities.

Keywords: Ethnic groups, Race, Questionnaire design, Population health, Surveys

Résumé

Objectifs

Les minorités visibles sont un groupe catégorisé dans la recherche en santé pour repérer et suivre les inégalités ou pour étudier les incidences de la racisation. Nous avons comparé les classifications obtenues d’un indicateur d’usage courant (norme de Statistique Canada) à celles obtenues par deux questions directes : la personne est-elle membre d’un groupe de minorité visible, et est-elle perçue ou traitée comme une personne de couleur?

Méthode

Une analyse à méthodes mixtes a été menée à l’aide des données d’un sondage en ligne en anglais (n = 311) et d’entretiens cognitifs avec un sous-ensemble à diversification maximale (n = 79). Les participants étaient des résidents canadiens de 14 ans et plus.

Résultats

La concordance entre l’élément « minorité visible » à lui seul et la norme était bonne (indice Kappa de Cohen = 0,725; IC de 95 % = 0,629, 0,820). Par contre, les participants ont interprété les mots « minorité visible » de façons différentes et souvent littérales, en comptant parfois les personnes visiblement handicapées, transgenres ou pauvres. La concordance entre l’élément « personne de couleur » à lui seul et la norme était très bonne (Κ = 0,830; IC de 95 % = 0,747, 0,913). L’expression « personne de couleur » était plus clairement comprise comme reflétant des antécédents ethnoraciaux et pourrait mieux saisir le groupe susceptible d’être la cible de racisme que la norme de Statistique Canada. Quand les participants autochtones qui disaient être des personnes de couleur ont été reclassifiés en fonction de la définition gouvernementale d’une minorité visible comme étant non autochtone, cet indicateur concordait très bien avec la norme fédérale actuelle (Κ = 0,851; IC de 95 % = 0,772, 0,930).

Conclusion

Une question unique sur la perception ou le traitement en tant que personne de couleur semble bien identifier les personnes racisées et pourrait sinon être recodée pour se rapprocher de la classification gouvernementale des minorités visibles.

Mots-clés: Ethnies, Race, Conception de questionnaire, Santé de la population, Enquêtes

Introduction

Data are often stratified by socio-demographics to assess population inequalities in health outcomes. In Canada, ethnoracial categories form one key equity stratifier, a characteristic used to identify population subgroups for which numeric inequalities in health or health care may indicate social inequity (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2018). Comparison of health indicators across equity stratifiers informs health equity interventions grounded in human rights (Bambas 2005). In addition to serving as equity stratifiers, ethnoracial classifications are used as an indicator of racialization, and the potential to be impacted by racism. Racialization is defined by the Ontario Human Rights Commission as the social process constructing races as “real, different, and unequal in ways that matter to economic, political, and social life.”(Ontario Human Rights Commission 2016). Bodies (e.g., skin, hair), behaviours (e.g., clothing), and social practices (e.g., accent, name) are all racialized, albeit in different ways.

People’s perceptions of race and identity impact how they view themselves and others, and their experiences in society (Eisenhower et al. 2014). While all bodies are racialized, the attachment of certain constructions of race by society to some groups (and not others) based on skin colour or ethnic origins can create inequality in treatment. Racialized people experience disparities in poverty, employment, and access to health services (Levy et al. 2013; Galabuzi 2005; Block and Galabuzi 2011). In order to study both inequalities and potential effects of racialization, we need survey measures that accurately capture this construct. In this paper, we compare the Statistics Canada standard for visible minority classifications with two single-item measures: one that asks whether one is a member of a visible minority group and another asking if one is perceived or treated as a person of colour.

The term “visible minority” was coined by activist Kay Livingstone in 1975 (Wharton-Zaretsky 2000) and implemented by the Canadian government under its Employment Equity Act in 1986 to promote equal opportunity for those “other than Aboriginal people, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour” (Statistics Canada 2016). Thus the intent of identifying visible minorities has been to assess and reduce inequalities resulting from perceptions of race or ethnicity, i.e., racialization.

In Canada, population demographic data are largely collected by Statistics Canada, which aims to support informed decision-making by government, businesses, nonprofit organizations, and individual Canadians. Other governmental organizations and investigator-driven studies often follow the Statistics Canada standards for comparability and credibility. The standard item for ethnoracial category surveys different races and ethnicities (white, South Asian, Arab, Chinese, Black, Filipino, Southeast Asian, West Asian, Latin American, Japanese, Korean, “other”) and asks participants to mark all that apply (Statistics Canada 2016). This question is then used to derive an ethnoracial group variable (termed “population group”), as well as a binary visible minority variable. Those who select only groups other than white or Aboriginal, or who select white in combination with certain groups (Chinese, South Asian, Black, Filipino, Southeast Asian, Japanese, Korean), are coded as visible minorities (Statistics Canada 2016). Those who indicate they are Aboriginal, white only, or white in combination with Latin American, Arab, or West Asian are classified as not visible minorities (Statistics Canada 2016). This classification serves as an approximation for those who are “non-white in colour” and may not reliably capture those who are racialized as persons of colour. Moreover, the exclusion of Indigenous persons from “visible minority” regardless of visibility may make this an even poorer proxy for racialization. Thus, the visible minority categorization may not be congruent with one’s visibility as racialized, especially for Indigenous or multi-racial individuals. This raises questions of whether this measure accurately captures this construct and whether a shorter, more direct question might perform well for researchers studying the effects of racialization or racism on health.

While “visible minority” reflects a government classification, its colloquial use may not make reference to the government definition. For example, an equity measure for grant applicants to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) asks if applicants “identify as a member of a visible minority,” without requiring one to specify which group (Canadian Institutes of Health Research n.d.) A term more commonly used to identify racial and ethnic minorities is “person of colour,” “a term which applies to all people who are not seen as [w]hite by the dominant group [… that] emphasizes that skin colour is a key consideration of the ‘everyday’ experiences of their lives” (Ontario Human Rights Commission 2009). While investigator-driven research has sometimes included a question asking participants to self-report whether they are perceived or treated as a person of colour (Trans PULSE Provincial Survey 2009), such items have not been evaluated. Thus, our objectives are to understand how Canadians from diverse backgrounds understand the terms “person of colour” and “visible minority” and to assess the extent to which responses to single-item survey questions based on each of these terms agree with each other and/or with the Statistics Canada standard for classifying visible minorities. Ultimately, we aim to assess whether single survey items may be useful in studying racialization and its impacts on health.

Methods

Sampling and recruitment

Cross-sectional, mixed-methods data were collected between October 2015 and March 2016 (Bauer et al. 2017; Dharma and Bauer 2017). Residents of Canada aged 14 or older with the ability to complete an online English-language survey were eligible to participate. Those under age 18 were included as ethnoracial items are regularly asked at young ages in adolescent health surveys and Statistics Canada surveys. Convenience sampling targeting specific groups including immigrants and gender/sexual minorities was implemented by recruiting participants using Facebook ads and Facebook postings, through emails to listservs and service organizations, and by electronic snowball sampling. Facebook and listservs have been shown to perform well for targeted sampling, including among older Canadians (King et al. 2014). An initial online survey containing socio-demographics and one of the single-item measures on race/ethnicity was completed by 588 participants, 311 of whom consented to recontact and completed a follow-up survey including the second single-item measure on race/ethnicity within the following 3 weeks. Those who completed the follow-up survey did not statistically differ from those who completed only the first survey on province, education, immigration history, first language, or Statistics Canada visible minority status. They were slightly more likely to be younger or older than ages 35 to 54 (p = 0.0201).

Of participants who agreed to be recontacted, a maximum diversity subgroup were invited to complete semi-structured cognitive interviews about their decision-making on survey items immediately after their follow-up survey. Potential interviewees were selected to ensure adequate representation based on age, sexual orientation and gender identity, geography, immigration and linguistic backgrounds, Indigeneity, race/ethnicity, education, and religiosity. Interviews (n = 79) were conducted via telephone or Skype, were transcribed verbatim, and lasted between 24 and 81 min. While the online survey was not incentivized, interview participants were given a $50 gift card. Ethics approval was granted by Western University’s Non-Medical Research Ethics Board.

Survey measures

Three measures were compared for this evaluation (see Table 1). The first was the “visible minority” standard (Statistics Canada 2015a), derived from two items called the Aboriginal group and population group questions (Statistics Canada 2016). Indigenous participants who reported being First Nations, Métis, or Inuit were not given the population group question which prompts participants to mark which of 11 ethnoracial groups they belong to, allowing for multiple, write-in, and “do not know”/refusal responses. Responses to these items were coded into a binary visible minority variable, per Statistics Canada standards (Statistics Canada 2016).

Table 1.

Evaluation survey items

| Statistics Canada items on Aboriginal identity and population group (adapted slightly from General Social Survey) (Statistics Canada 2015b) | |

| Are you …? | |

| First Nations (Status or non-status) | |

| Métis | |

| Inuk (Inuit) | |

| None of the above | |

| Do not know | |

| You may belong to one or more racial or cultural groups on the following list. Are you...? (Mark up to 6 responses) | |

| White | |

| South Asian (e.g., East Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan) | |

| Chinese | |

| Black | |

| Filipino | |

| Latin American | |

| Arab | |

| Southeast Asian (e.g., Vietnamese, Cambodian, Malaysian, Laotian) | |

| West Asian (e.g., Iranian, Afghan) | |

| Korean | |

| Japanese | |

| Another group ________________ | |

| Do not know | |

| Person of colour item (Trans PULSE Provincial Survey 2009) | |

| Are you perceived or treated as a person of colour? | |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| Visible minority item | |

| Are you a member of a visible minority group? | |

| Yes | |

| No |

The second measure was a single question developed by the Trans PULSE Project team to capture racialization and potential for exposure to racism: “Are you perceived or treated as a person of colour?”(Trans PULSE Provincial Survey 2009). The third was a test question simply asking “Are you a member of a visible minority group?” While created by our team, this item closely parallels newer items such as in the CIHR Equity and Diversity Survey (Canadian Institutes of Health Research n.d.).

Additional socio-demographic measures were used to characterize survey and interview samples, identify the composition of discordant groups on the three measures, and describe interview participants in qualitative analysis. Participants self-reported their age, first language, religion, and degree of religiosity. Items on education (modified) and sexual orientation were taken from the Canadian Community Health Survey (Statistics Canada 2014). Province/territory of residence was identified from the first letter of postal code. First-generation Canadians were those who indicated having two immigrant parents, while multigeneration Canadians had at least one parent who was born Canadian. Sex and gender were measured by asking participants their current gender identity and sex assigned at birth (The GenIUSS Group 2014), with gender identity (including write-ins) recoded into three broad categories. These variables were cross-coded to identify transgender participants (Bauer et al. 2017).

Interview questions

Cognitive interview participants were asked seven questions on race and ethnicity in the context of population surveys and in general life (Table 2). Questions included probes to prompt elaboration on responses, including a question on whether the terms “person of colour” and “visible minority” have different meanings. Questions focused on the two single-item measures rather than the Statistics Canada standard.

Table 2.

Cognitive interview questions on race and ethnicity

| How did you decide how to answer these questions? | |

| What do the words “person of colour” and “visible minority” mean to you? | |

| Probes: | |

| Are they different? | |

| Do they relate to discrimination? | |

| Are they positive, negative or neutral words? | |

| (If first language is not English) What types of words does your own language have for people of your appearance, your ethnicity or your group? | |

| Probe: | |

| Do they mean different things than in English? | |

| How do you understand your own “race”? “Ethnicity”? How do you identify yourself? | |

| Probes: | |

| Has this understanding changed over time? Has the way you describe yourself…? | |

| Do you describe yourself differently in different situations or with different groups (e.g., with friends, family, relatives)? (with regard to race or ethnicity) | |

| If surveys could ask questions in ways that would make most sense to you, how should they ask about race and ethnicity? | |

| Is it important to include this information? Why or why not? | |

| Is there anything else we have not talked about yet that you feel is important to aspects of your race or ethnicity? |

Mixed-methods analysis

Quantitative analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS software 2013) and qualitative using NVivo version 11 (NVivo 2015). Initial qualitative and quantitative analyses were conducted in parallel with triangulation between results (Creswell and Clark 2011), with additional qualitative analyses guided by both the quantitative findings and our qualitative priority of understanding meaning (Hesse-Biber 2010).

All interview transcripts were analyzed to understand individual interpretations of terms, questions, and response options. Qualitative analysis was guided by an inductive approach that prioritized participants’ understandings and experiences (Hesse-Biber 2010), with regard to race and ethnicity. The authors collaboratively created a codebook that sought to capture these.

The responses for each pair of survey measures were cross-tabulated to gauge where agreement and discordance occurred, using Cohen’s kappa (Cohen 1960). Kappa indicates the probability, beyond chance, that two measures classify a given individual into the same group. Sensitivity and specificity of the measures were calculated, using the Statistics Canada standard as the reference. While not necessarily the “gold standard” for identifying those who are “non-white in colour” (Statistics Canada 2015a) or who experience racism, we use this comparison to understand how the measures differ. Where these measures disagreed, members of discordant cells were coded for further qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Discordant cells were characterized by socio-demographics to understand whether members in the cells shared any traits. Members’ interview transcripts were analyzed specifically for distinctions made between terminology and measures that would have informed their survey response decisions.

Results

Sample composition

Socio-demographic characteristics of survey and interview participants are summarized in Table 3. Of the 311 survey participants, the greatest number of individuals were in the following categories: 25- to 34-year-old (36.3%), multigenerational (68.2%), white (82.3%, alone or in combination with other identities), non-Indigenous (94.8%), heterosexual (48.7%), agnostic or atheist (46.6%), female-identified (68.7%), Ontario residents (55.6%), with a postsecondary degree/diploma (77.5%). No one from the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Yukon Territory, or Prince Edward Island completed the survey.

Table 3.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

| Survey sample N = 311 | Interview sample N = 79 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age | ||||

| 14–18 | 17 | 5.5 | 7 | 8.9 |

| 19–24 | 50 | 16.1 | 15 | 19.0 |

| 25–34 | 113 | 36.3 | 21 | 26.6 |

| 35–44 | 60 | 19.3 | 15 | 19.0 |

| 45–54 | 35 | 11.3 | 7 | 8.9 |

| 55–64 | 33 | 10.6 | 13 | 16.5 |

| 65+ | 3 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Sex at birth | ||||

| Female | 237 | 76.7 | 51 | 64.6 |

| Male | 72 | 23.3 | 28 | 35.4 |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Female/woman | 213 | 68.7 | 42 | 53.9 |

| Male/man | 61 | 19.7 | 23 | 29.5 |

| Genderqueer, non-conforming, or other | 36 | 11.6 | 13 | 16.7 |

| Province/territory | ||||

| Northwest Territories, Nunavut, or Yukon | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alberta | 20 | 6.4 | 8 | 10.1 |

| British Columbia | 57 | 18.3 | 21 | 26.6 |

| Manitoba | 7 | 2.3 | 4 | 5.1 |

| New Brunswick | 16 | 5.1 | 6 | 7.6 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Nova Scotia | 14 | 4.5 | 4 | 5.1 |

| Ontario | 173 | 55.6 | 25 | 31.7 |

| Prince Edward Island (PEI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quebec | 11 | 3.5 | 7 | 8.9 |

| Saskatchewan | 11 | 3.5 | 3 | 3.8 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 9 | 2.9 | 4 | 5.1 |

| High school diploma | 14 | 4.5 | 7 | 8.9 |

| Some postsecondary | 47 | 15.1 | 15 | 19.0 |

| Postsecondary degree or diploma | 241 | 77.5 | 53 | 67.1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Indigenous | 11 | 3.6 | 8 | 10.3 |

| White (non-Indigenous) | 235 | 76.0 | 37 | 44.4 |

| Racialized (non-Indigenous) | 63 | 20.5 | 33 | 42.3 |

| Race/ethnicity1 | ||||

| White | 256 | 82.3 | 52 | 65.8 |

| South Asian | 11 | 3.5 | 7 | 8.9 |

| Chinese | 19 | 6.1 | 8 | 10.1 |

| Black | 11 | 3.6 | 8 | 10.4 |

| Filipino | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Latin American | 7 | 2.3 | 4 | 5.2 |

| Arab | 3 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Southeast Asian | 7 | 2.3 | 3 | 3.8 |

| West Asian | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Korean | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Japanese | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Another group | 7 | 2.3 | 5 | 6.3 |

| Indigenous identity | ||||

| First Nations, Métis, Inuit | 11 | 3.6 | 8 | 10.1 |

| Non-Indigenous | 294 | 94.8 | 68 | 86.1 |

| Do not know | 5 | 1.6 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 75 | 24.1 | 18 | 22.8 |

| Muslim | 9 | 2.9 | 6 | 7.6 |

| Jewish | 16 | 5.1 | 4 | 5.1 |

| Sikh, Hindu, Buddhist, Neo-pagan | 23 | 7.4 | 8 | 10.1 |

| Agnostic or atheist | 145 | 46.6 | 28 | 35.4 |

| Other | 35 | 11.3 | 12 | 15.2 |

| Religiosity | ||||

| Religious | 35 | 11.3 | 10 | 12.7 |

| Somewhat religious | 75 | 24.2 | 20 | 25.3 |

| Not religious | 212 | 64.5 | 49 | 62.0 |

| Immigration history | ||||

| Immigrant | 52 | 16.7 | 17 | 21.5 |

| First generation | 47 | 15.1 | 20 | 25.3 |

| Multigeneration or Indigenous | 212 | 68.2 | 42 | 53.2 |

| First language | ||||

| English | 267 | 85.9 | 62 | 78.5 |

| French | 7 | 2.3 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Other | 37 | 11.9 | 15 | 19.0 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 151 | 48.7 | 26 | 32.9 |

| Homosexual | 57 | 18.4 | 20 | 25.3 |

| Bisexual | 84 | 27.1 | 22 | 27.9 |

| Do not know | 18 | 5.8 | 11 | 13.9 |

| Visible minority—Statistics Canada | ||||

| Yes | 58 | 18.8 | 30 | 38.5 |

| No | 251 | 81.2 | 48 | 61.5 |

| Visible minority—self-reported | ||||

| Yes | 71 | 22.8 | 36 | 45.6 |

| No | 240 | 77.2 | 43 | 54.4 |

| Perceived/treated as person of colour | ||||

| Yes | 50 | 16.1 | 29 | 37.2 |

| No | 261 | 83.9 | 49 | 62.8 |

1Respondents could check multiple options; therefore, frequencies will sum to greater than 100%

Cognitive interview participants were more evenly distributed across socio-demographic categories by design. Of the participants, 18.8% of survey participants and 38.5% of interview participants were classified as visible minorities using the Statistics Canada standard; corresponding proportions were 22.8% and 45.6% for self-identified visible minorities and 16.1% and 37.2% for reporting being perceived or treated as persons of colour.

General understandings of single questionnaire items

Most participants understood both the “visible minority” and “person of colour” measure to be about race and ethnicity. Individuals who identified themselves as white only or Black only found both the visible minority question and the person of colour question to be easy to answer. Other participants racialized as non-white found these questions more difficult.

Generally, participants found the person of colour question to be clearer than the visible minority question, though a few found both confusing. Common conceptual issues with the visible minority measure centred on vagueness, and a literal interpretation based on both visibility and/or minority status. Participants mentioned visible minority as potentially based on ethnoracial group, disability, poverty, religion, gender (both cisgender women and transgender persons), and sexual orientation. Regarding the person of colour question, some found the “perceived or treated as” part of the question conflicting. For instance, a South Asian male from Ontario discussed how even though he was brown and therefore perceived as a person of colour, he “would probably say no” to the question, as he did not feel as though he was generally treated as a person of colour.

Agreement between measures

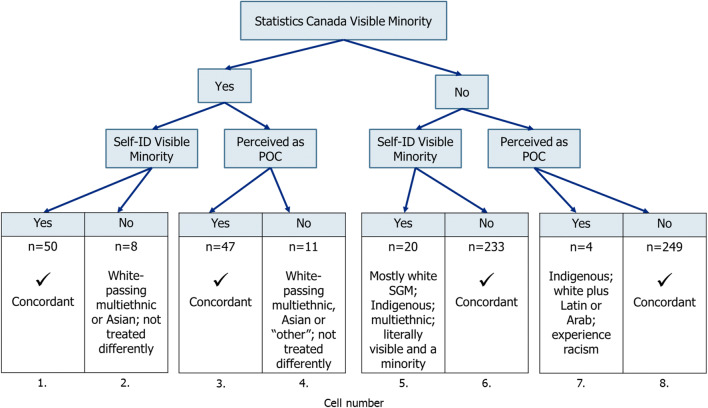

Concordancy and discordancy are presented in Fig. 1, while sensitivity, specificity, and agreement between measures are reported in Table 4. When the self-reported visible minority measure was compared with the Statistics Canada standard, sensitivity was 86.2%, specificity was 92.0%, and chance-corrected agreement was 0.725 (95% CI 0.629, 0.820). If Indigenous participants were reclassified as not visible minorities to align with the Employment Equity Act definition, sensitivity remained 86.2%, specificity improved to 93.2%, and chance-corrected agreement was 0.749 (95% CI 0.657, 0.842), indicating moderate agreement. When the person of colour measure was compared with the standard, sensitivity was 80.7%, specificity was 98.4%, and chance-corrected agreement was 0.830 (95% CI 0.747, 0.913). Upon reclassifying Indigenous participants, sensitivity remained 80.7%, specificity improved to 99.2%, and chance-corrected agreement was 0.851 (95% CI 0.772, 0.930), indicating strong agreement. As expected, reclassification of Indigenous participants improved specificity and did not change sensitivity, given that it shifted participants in a single direction. When the person of colour measure was compared with the self-reported visible minority measure, chance-corrected agreement was 0.713 (95% CI 0.614, 0.811), indicating moderate agreement.

Fig. 1.

Concordancy and discordancy on measures

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, and agreement between measures (N = 311)

| Sensitivitya | Specificitya | Chance-corrected agreement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Se | 95% CI | Sp | 95% CI | K | 95% CI |

| Visible minority item vs. standard | 0.862 | 0.746, 0.939 | 0.920 | 0.879, 0.951 | 0.725 | 0.629, 0.820 |

| Person of colour item vs. standard | 0.807 | 0.681, 0.900 | 0.984 | 0.960, 0.996 | 0.830 | 0.747, 0.913 |

| Visible minority item vs. standard, with Indigenous reclassification | 0.862 | 0.746, 0.939 | 0.932 | 0.893, 0.960 | 0.749 | 0.657, 0.842 |

| Person of colour item vs. standard, with Indigenous reclassification | 0.807 | 0.681, 0.900 | 0.992 | 0.971, 0.999 | 0.851 | 0.772, 0.930 |

| Visible minority item vs. person of colour item | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.713 | 0.614, 0.811 |

aStatistics Canada standard as the reference

Self-reported visible minorities who were not Statistics Canada visible minorities

Contrary to the Statistics Canada standard, 20 participants indicated they were visible minorities. Of these, 15 were white only, 2 multiethnic, and 3 First Nations. Nine identified as transgender while 1 was unsure, and 12 classified themselves as homosexual or bisexual while 5 checked “do not know.” Ages ranged from 14 to 64. Participants were from Ontario, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Alberta, New Brunswick, and Quebec.

Most often, these participants used their experience of gender and/or sexual orientation to decide whether they were visible minorities. For example, one white pansexual transfeminine participant from New Brunswick said, “I consider myself being a member of visible minority group because I am a trans individual. So by that very definition, I am an extreme minority at one and a half percent of the community.” Another participant, a white trans woman from Quebec used sexuality as one of multiple possible dimensions of minority status, explaining that “there’s multiple different minorities … different levels, and it can be … double, triple, even quadruple minorities at some point. You can be LGBT, you can be part of the asexual group, and then you can just keep going on and on like that.”

White sexual and gender minority participants noted the importance of context in interpreting the visible minority question. A white transfeminine participant stated, “in certain contexts, I can be a very visible minority, but in others, I would certainly assume that when they’re talking about visible minorities, that they would mean people of colour.” Similarly, a white homosexual woman from Alberta said, “I would probably personally say no [to being a visible minority] unless I knew it was a specific gender survey.” This participant believed that being a woman would give someone visible minority status because to her, “visible minority is anything that you can pinpoint they are not of the majority just by looking at them”; she implied that “majority” would seem to be able-bodied white men. For white participants then, responding “yes” to the visible minority question was not about race or ethnicity but about other dimensions that are socially demarcated as visibly different.

Three of the eleven Indigenous survey participants identified as visible minorities contrary to the Statistics Canada standard. They spoke of skin colour as shaping their answers. As one First Nations man from British Columbia explained, he answered “yes” to the visible minority question because “… there’s some folks that identify as Indigenous who you wouldn’t be able to tell necessarily because they don’t appear to be a person of colour, a dark skinned Indigenous person. So that term makes a lot of sense to me [as a dark-skinned Indigenous person].” For Indigenous participants, experiences of visibility and racialization were central to their decision-making.

Statistics Canada visible minorities who were not self-reported visible minorities

Eight participants (Fig. 1, cell 2) classified as visible minorities under the Statistics Canada standard self-reported they were not a part of a visible minority group. Within this group, 3 identified as both white and another ethnoracial group, and 5 identified as only West Asian, Chinese, Korean, or South Asian. By definition, nobody in this group was Indigenous. The age range was from 14 to 64, with the majority (5) aged 19 to 34.

Individuals within this second discordant cell used complex understandings of racialization to make decisions on this measure. Their decision-making processes complicate Statistics Canada’s use of ethnoracial identities to denote visible minorities as “non-white in colour” (Statistics Canada 2015a), as appearing white (at least some of the time) was central to some participants’ responses. Also central was a perceived lack of social disadvantage. For example, one Chinese and white woman from Ontario who described being perceived as white in some instances and not others said, “The question is, ‘Are you a visible minority?’ I don’t know. Sometimes I am and sometimes I’m not. … I deliberately put ‘no’ … because my sense of minority is based on a construct of privilege, and so I can’t—I don’t know what they’re trying to insinuate from that question, but if being a visible minority … is like a disadvantage—then I’m not disadvantaged.” Participants who did not appear white similarly described the context in which their racialized bodies were located as shaping if and when they were visible minorities. One female South Asian teenager from Ontario explained, “I am not white, I am brown … I’m certainly not like most people are here. But Canada is different … I’m brown, but I’m not treated any differently.” For this participant, skin colour and ethnoracial identity were not inherent indicators of visible minority status.

Last, for some participants in this group, other dimensions were more important in considering their own visible minority status than their ethnoracial group. For example, one white and Caribbean participant from Ontario with a queer sexuality and non-binary gender stated “I would say I’m visibly queer … I actually had yes [to the visible minority question], and then went back and switched it to no, just because there are visible minorities that don’t have that – that ebb and flow between perception of them. It’s like if you’re black, you’re black, and people see you as black. You are a visible minority.” This participant based their response on the consistency of visibility. For them personally, the consideration was in the visibility of their queerness rather than their ethnoracial background, and their queerness was not as consistently visible as some other people’s race, in particular for Black people.

Self-reported persons of colour who were not Statistics Canada visible minorities

Four participants indicated they were perceived or treated as persons of colour, though Statistics Canada would not classify them as visible minorities. Two identified as Indigenous men, and two were multiethnic: one white and Arab, and the other white and South American. Statistics Canada specifically excludes multiethnic people of these origins from the visible minority standard. However, this did not mean that these participants never experienced racialization. One female participant recalled social situations where their Latin American background was exoticized, “…I’m hesitant to define myself as a person of colour, but do I get treated as one? I get dehumanized because of how I look, and I get dehumanized because of my half-Chilean-ness, so I think that qualifies as a person of colour experience.”

Of the two Indigenous men, one resided in Ontario and the other in British Columbia. For both, decision-making was shaped by experiences of racialization. When asked why he chose “yes” to the person of colour question, one responded, “My parents are both First Nations, so I have non-white skin and growing up on a reserve, in a mixed community of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, I have been faced with different kinds of adversity, but because of my skin colour.” The other man similarly responded, “I’m a dark-skinned person. And so in terms of understanding of race and racism, race theory, you know, I identify as a person of colour.” Both participants associated being a person of colour with skin colour, racism, and discrimination.

Statistics Canada visible minorities who were not self-reported persons of colour

Eleven participants indicated they were not perceived or treated as persons of colour, but were classified as Statistics Canada visible minorities (Fig. 1, cell 4). For ethnoracial group, 3 indicated they were both white and another group; 6 only Chinese, South East Asian, or West Asian; and 2 “other.” Most (8) resided in Ontario. For some, the discordance between the two measures may be due to their own identification, skin colour, and/or cultural connections. One white and Caribbean interview participant in this group noted that they would identify racially as white, and ethnically as Canadian. When asked about their race they responded, “Well, I identify as white because the colour of my skin is white.” This participant noted they “never felt mixed” and further explained this as “mostly because my dad doesn’t have strong ties to his cultural roots.” While their racial identity was tied to skin colour, “person of colour” was also considered in relation to cultural ties. Unfortunately, interview data were not available for more individuals in this discordant category, to further understand why others did not self-report as persons of colour.

Self-reported visible minorities who were not self-reported persons of colour

There were twenty-four participants who said they were part of a visible minority group but not perceived or treated as persons of colour, with 15 being white and 10 residing in Ontario. Fourteen indicated they were homosexual or bisexual while 4 checked the “other” box, and 10 were transgender. As with our comparison of the visible minority measure to the Statistics Canada measure, most white individuals who self-identified as visible minorities but not perceived or treated as persons of colour were sexual and/or gender minorities and used this to inform their decisions.

While the 9 non-white or multiethnic participants who indicated they were visible minorities but not persons of colour answered the visible minority question based on visible differences that included ethnoracial group, religion, and gender, it was unclear why they did not correspondingly identify as persons of colour.

Self-reported persons of colour who were not self-reported visible minorities

There were four participants who said they were not members of a visible minority group but were perceived or treated as persons of colour; all were Chinese, Korean, or South Asian. There were an equal number of women and men, with 3 being from Ontario and 2 aged 14 to 18. While reasons for discordance varied, each person made a general connection to social context (e.g., they are not white but blend in with the others). As noted before, some participants were uncertain of the definition of “visible minority” and understood it to include groups other than ethnoracial minorities. One heterosexual male Korean participant, when asked what the term meant, responded, “It could be about homosexuals or any group that isn’t the majority.” Another South Asian participant responded by saying, “I feel like only for some reason just Aboriginal people are put into this category versus other cultures and religions” and then suggested people living with disabilities may also be included. Both these participants clearly understood the meaning of “person of colour,” which may be easier to understand cross-culturally, or for individuals for whom English is not their first language (as was the case for 3 of the 4 in this group). The Korean participant reacted positively to “person of colour” saying, “Even in Mandarin, they use the word ‘yellow’ in describing Asians. So I guess in my head, that’s pretty easy and clear for that answer, yes.” This multilinguistic association of colours with people could be an advantage when surveying people for whom English is not a first language or who are not familiar with Canadian terminology.

Discussion

We have conducted the first evaluation of single-item survey measures to capture racialization. In general, Canadians understood the terms “visible minority” and “person of colour” as being intended to measure ethnoracial group, though multi-racial participants found it more challenging to understand these measures and suggested this difficulty was tied to their experiences of racialization.

Results indicate poorest performance for the visible minority measure. “Visible minority” was sometimes interpreted literally by both white and racialized individuals to include other groups, weighing out two main factors—visibility to others, and being a minority, variably defined by numbers or disadvantage. Moreover, the lowest agreement occurred between the self-reported visible minority measure and each of the other two measures. Of those who indicated they were a visible minority, but did not identify as a person of colour and/or were not coded as a visible minority under the Statistics Canada standard, the majority were sexual and/or gender minorities. These results are in accordance with the literature around sexual and gender minorities, where visual identifiers of gender nonconformity are associated with targetability for discrimination (Puckett et al. 2016; Miller and Grollman 2015). When provided without the context of race or ethnicity, “visible minority” may be misinterpreted, making it a poor choice for a survey question.

The Statistics Canada standard did capture some participants who did not self-identify as visible minorities and/or indicated they were not perceived or treated as persons of colour. One such group were multiethnic participants who were perceived at least some of the time as white, or did not believe they experienced disadvantage. For racial and ethnic minority individuals, being perceived as white can have an impact on their social interactions in terms of discrimination and racism (Ahmed 1999). The other main group were monoracial Asian participants, with two apparently different explanations. First, similarly to those sometimes perceived as white, some did not believe they experienced disadvantage; they felt like they “fit in” with their social environment. Second, some did not understand the meaning of “visible minority” as relating specifically to ethnoracial group, but consistently linked the term “person of colour” to race and ethnicity. To our knowledge, this is the first published cognitive testing of this terminology, and these represent novel findings.

Conversely, some self-identified persons of colour or visible minorities who were either Indigenous or both white and Arab, Latin, or West Asian were not considered to be visible minorities by the Statistics Canada standard, despite describing experiences of racialized adversity. These findings have implications for interpretation, as the Statistics Canada standard will exclude as “visible minorities” some who report being “non-white in colour” (Statistics Canada 2016) as per the regulatory and equity aims to which the measure is tied. Additionally, while Indigenous Canadians are classified by Statistics Canada separately under the Aboriginal group standard (Statistics Canada 2007), the Statistics Canada visible minority standard does not provide any measure of racialization for Indigenous peoples. This presents an issue when used in studies of racialization or potential for experiences of racism, as the standard’s ethnoracial groupings are a pr.oxy for racialization rather than a measure of the construct itself. This last issue is not unique to the Statistics Canada measure, as racialized groups are often categorized using singular categories (such as Black, white, South Asian) and single “mixed” categories for people from multiple origins (Kiran et al. 2019; Veenstra 2009).

With the Statistics Canada standard as the reference for both single-item measures, the person of colour question had a slightly lower sensitivity than the visible minority question, and a higher specificity. This is consistent with the patterns of classification described above, wherein the person of colour measure may have better discriminated based on racialization. This distinction from the Statistics Canada measure may be a positive feature of the person of colour measure, if researchers are looking to identify individuals who experience racialization. Overall agreement between the person of colour measure and the Statistics Canada standard was high and was even higher if Indigenous participants were reclassified as not visible minorities in keeping with the Employment Equity Act definition.

To our knowledge, this study is the first evaluation of simple single items to capture racialization or visible minority status. Limitations of this study include convenience sampling and that the study was conducted only in English. While comparable terminology exists in French—minorités visibles and personne de couleur—whether terms will be similarly understood in a francophone context requires additional cognitive testing, and terminology may vary across other languages. Future research should continue to explore understandings of single-item measures as both terminology and the social context for race and ethnicity evolve. Additional research can aim to explore how racialization relates to other dimensions of race/ethnicity, such as identity, ethnic heritage, community, and expression of ethnicity, as well as to experiences of stigma and discrimination.

This study has provided new insight into how Canadians conceptualize racialization and visible minority status and respond to single survey items. Given our results, we do not recommend using the single self-reported visible minority item, either as a shorter substitute for the Employment Equity Act-defined group or as a measure of racialization. In contrast, the person of colour item has the advantage of being a brief, dichotomous measure that appeared to capture racialization in a meaningful way while avoiding ascribing either one’s visibility or experiences of privilege and discrimination on the basis of their self-reported ethnoracial group(s). Given our results, we recommend the question “Are you perceived or treated as a person of colour?” as a simpler and potentially better measure of racialization, when that is the construct of interest. This single item could be used alone or in conjunction with the existing Statistics Canada Aboriginal group and population group questions—or other versions of survey items on Indigeneity and/or ethnoracial background—in order to measure racialization simply and more directly. For studies where racialization is of interest, it may in fact be both clearer and simpler to just ask.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ayden Scheim for contributions to the survey design and Christoffer Dharma for assistance with data collection and for comments on an earlier draft.

Funding information

Funding was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Gender and Health (FRN 130489).

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics approval was granted by Western University’s Non-Medical Research Ethics Board.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmed S. 1999. ‘She’ll wake up one of these days and find she’s turned into a nigger’: passing through hybridity. Theory, Culture and Society. 1999;16(2):87–106. doi: 10.1177/02632769922050566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bambas L. Integrating equity into health information systems: a human rights approach to health and information. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2(4):e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, Braimoh J, Scheim AI, Dharma Transgender-inclusive measures of sex/gender for population surveys: mixed methods evaluation and recommendations. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0178043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block S, Galabuzi G-E. Canada’s colour coded labour market: the gap for racialized workers. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information . In pursuit of health equity: defining stratifiers for measuring health inequality. Ottawa: CIHI; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (n.d.) How to complete the Equity and Diversity Questionnaire. Available at: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50959.html

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20(1):37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Dharma C, Bauer GR. Understanding sexual orientation and health in Canada: who are we capturing and who are we missing using the Statistics Canada sexual orientation question? Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2017;108(1):e21–e26. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.108.5848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhower A, Suyemoto K, Lucchese F, Canenguez K. “Which box should I check?”: examining standard check box approaches to measuring race and ethnicity. Health Services Research. 2014;49(3):1034–1055. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galabuzi G-E. The racialization of poverty in Canada: implications for Section 15 Charter protection. Ottawa: The National Anti-Racism Council of Canada National Conference; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse-Biber S. Qualitative approaches to mixed methods practice. Qualitative Inquiry. 2010;16(6):455–468. doi: 10.1177/1077800410364611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King DB, O’Rourke N, De Longis A. Social media recruitment and online data collection: a beginner’s guide and best practices for accessing low-prevalence and hard-to-reach populations. Canadian Psychologist. 2014;55(4):240–249. doi: 10.1037/a0038087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran T, Sandhu P, Aratangy T, Devotta K, Lofters A, Pinto AD. Patient perspectives on routinely being asked about their race and ethnicity: qualitative study in primary care. Canadian Family Physician. 2019;65(8):e363–e369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy J, Ansara D, Stover A. Racialization and health inequities in Toronto. Toronto: Toronto Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miller LR, Grollman EA. The social costs of gender nonconformity for transgender adults: implications for discrimination and health. Sociological Forum. 2015;30(3):809–831. doi: 10.1111/socf.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, 2015.

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2009). Policy and guidelines on racism and racial discrimination. Available at: http://www.ohrc.on.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/Policy_and_guidelines_on_racism_and_racial_discrimination.pdf

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. Racial discrimination, race and racism (fact sheet). Ontario Human Rights Commission. Available at: http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/racial-discrimination-race-and-racism-fact-sheet (Accessed 9 Nov 2016)

- Puckett JA, Maroney MR, Levitt HM, Horne SG. Relations between gender expression, minority stress, and mental health in cisgender sexual minority women and men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2016;3(4):489. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAS software. SAS Institute, Cary, NC. Version 9.4, 2013.

- Statistics Canada. How Statistics Canada identifies Aboriginal people. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, 2007. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/12-592-x/12-592-x2007001-eng.pdf

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey – 2014. Available at: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Instr.pl?Function=getInstrumentList&Item_Id=214314&UL=1V&

- Statistics Canada. Visible minority of person. Statistics Canada, 2015a. Available at: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DEC&Id=45152

- Statistics Canada . General social survey on time use. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . Visible minority and population group reference guide, Census of Population, 2016. Statistics Canada. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The GenIUSS Group . In: Best practices for asking questions to identify transgender and other gender minority respondents on population-based surveys. Herman JL, editor. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute; 2014. pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Trans PULSE Provincial Survey 2009. Available at: http://transpulseproject.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Trans-PULSE-survey-information-only-copy-2012.pdf

- Veenstra G. Racialized identity and health in Canada: results from a nationally representative survey. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(4):538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton-Zaretsky M. Foremothers of Black women’s community organizing in Toronto. Atlantis. 2000;24(2):61–71. [Google Scholar]