Abstract

Social media, particularly podcasts, has become an influential modality within informal medical education. As podcasts continue to become more prevalent among learners of all types, clinical educators of the future must be able to help navigate this new pedagogy. Preliminary data demonstrates that medical students, residents, post-training physicians, and advanced practitioners all utilize podcasts for their own benefit. New data is discussed in the setting of the current literature on podcasting and important questions remain to determine how this new form of learning can and will be integrated into formal and informal medical curriculum.

WHAT WE KNOW

“I heard on a podcast1 that pickle juice could help with Mrs. R’s muscle spasms...” Statements like this are more common in the clinics and wards as learners use new educational modalities to supplement their learning. As podcasts become more prevalent, clinician-educators must seek a greater understanding of how this new form of knowledge dissemination fits into current educational programming.

Both graduate and undergraduate medical educators are incorporating asynchronous learning and “flipped classroom” pedagogies.2 Podcasts brings a novel and popular addition to the educator’s armamentarium. Several residency programs, particularly in Emergency Medicine (EM), have integrated digital education resources into formalized graduate medical education.3 Subspecialties such as Nephrology have embraced podcasts and the “Social Media Revolution” in education.4 Podcasts in particular have grown exponentially relative to other asynchronous medical education resources.3

Many residents use and prefer podcasts to supplement their education. One survey of 356 EM residents found that 88% reported listening to medical education podcasts at least once a month.5 Another study of 226 EM residents identified podcasts as the most popular form of extracurricular education and as the most beneficial learning method compared to textbooks, journals, and Google.6 More recently, podcasts have gained similar popularity in Internal Medicine. The Curbsiders Internal Medicine podcast averages over 40,000 downloads per weekly episode. Podcast producers include not only individual practitioners and educators (e.g., The Curbsiders, Annals on Call, Core IM, Bedside Rounds, Clinical Problem Solvers) but also influential medical journals (e.g., JAMA, NEJM, Annals of Internal Medicine). We are only beginning to appreciate the extent and degree of the changing landscape.

PRELIMINARY DATA

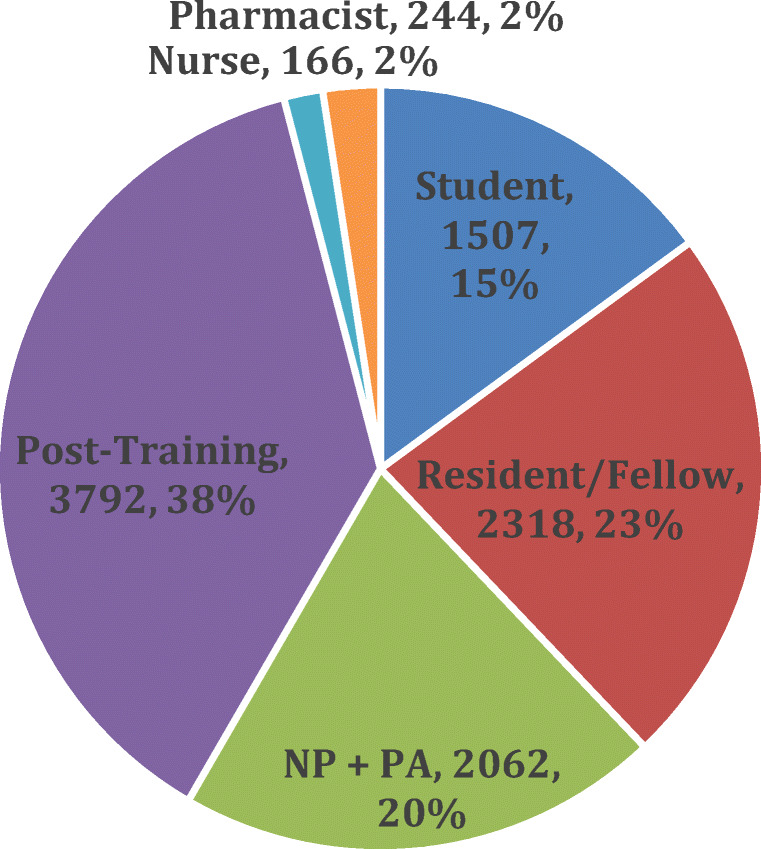

Who listens to medical education podcasts? Using self-reported data from an internally collected survey of 10,089 subscribers to The Curbsiders, approximately 38% identified as internists, specialists, faculty, or post-training physicians; 23% as residents or fellows; 20% as advanced practitioners (e.g., physician assistants or nurse practitioners); and 15% identified as students (see Fig. 1). Listeners clearly extend across the spectrum of practitioners, educators, and trainees.

Fig. 1.

Demographics of The Curbsiders mailing list subscribers (n = 10,089).

Many podcasts now offer Continuing Medical Education (CME) and Maintenance of Certification (MOC) credits. The CME/MOC credits are sponsored through societal organizations like American College of Physicians (ACP) and Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). In the past 6 months, 4730 CME credit have been claimed for “Annals On Call,” a popular podcast produced by Annals of Internal Medicine and hosted by Dr. Robert Centor.

WHAT IS YET TO BE EXPLORED

Our data suggest that medical education podcasts are being adopted at all training levels. We note that students are a substantial portion of the podcast subscriber pool, other research confirms wide use by residents, and our CME utilization data demonstrates use after training. This asynchronous learning is, as others have stated, “a paradigm shift in education.”6 The increasing popularity of Internal Medicine podcasts suggest an unmet need now being addressed with a new educational modality. What are those unmet needs and what can we learn from and deduce from this rapid adoption?

Podcasting adds several potential benefits for learners. First, convenience allows learners to listen while cooking dinner, commuting to work, exercising, or engaging in other activities. In an era of increasing demands on physician time, this feature provides greater flexibility when compared to other learning opportunities. Listeners have identified podcasts as a more efficient and enjoyable way to keep up to date.7 Second, podcasting offers exposure to international expertise that may not otherwise be accessible. Third, the format creates a low-stress atmosphere that is less intimidating to learners. Podcasts create low-stakes dialogue that engenders a positive learning environment. Indeed, though podcasting utilizes innovative technologies, the ultimate pedagogy reflects back to an oral tradition of learning medicine. These benefits align with Knowles’ theory of andragogy, empowering adult learners to plan their own content and ensure it is directly relevant.

Questions regarding best practices remain. How do we best utilize portable, just in-time learning to improve medical education for learners of all training levels? Are there specific characteristics (style, duration, production level) of podcasts that are associated with wide dissemination, improved knowledge retention, or improved clinical practices? Many of the more popular medical education podcasts offer a casual tone and “show notes” that offer visual summaries of topics discussed or links to enable learners to find primary sources mentioned.

Existing literature shows reasonable knowledge uptake through similar “flipped classroom” digital innovations, though there is mixed data on changes of clinical practices.2 Some initial quality indicators of podcasts have been identified by clinical educators8 and attempts have been made to critically evaluate online medical education resources.9 But does convenience of these modalities facilitate learning while multitasking or take away from focused study? Future studies can offer more robust investigation to determine how podcast practices affect higher levels of cognition within Bloom’s taxonomy of learning.

The rapid uptake of podcasts has implications for clinical instructors. Medical educators of the future will need to be early adopters of technology and act as a coach to determine the best ways to navigate these resources.10 For example, what shape will critical appraisal of these “free open access medical education” (“FOAM”) resources take? Will there be journal clubs for podcast episodes? Should there be formal peer-review? Similar to point-of-care ultrasound training, educators need to be intimately familiar with new technologies to help guide their use. Modern clinical educators will need to be the curators of valuable resources available online, role models for professional engagement with social media tools, and serve as coaches in the evolving field of digital scholarship.

Harnessing this technology may do more than just increase knowledge retention.11 Perhaps it may help combat some of the more “wicked” problems facing medicine today. Social media such as Twitter and podcasts have the potential to make explicit and positively influence the “hidden curriculum,” which at times can be toxic and perpetuate moral injury. Producers of podcast content can serve as role models for curiosity, camaraderie, and professional satisfaction for novice learners. Social learning theory asserts that individuals learn by observing others12; in the case of podcasts, listening to others may not only disseminate medical knowledge but engage in critical thinking and sharing cultural competencies. Core IM recently released a new series called “At the Bedside” that gives a space to speak openly about common issues that fall outside of the traditional realm of evidence-based medicine, such as approach to “difficult” patients or advantages and pitfalls of dark “gallows humor” in Medicine. Podcasts are virtual communities of practice. Unlike one’s static institutional environment, podcasts offer learners an opportunity to tune in to the community of practice of their choosing. What impact might this have on sharing values or finding role models in the field of medicine?

Podcasting will inevitably become a core component of medical education, either formally or informally. As more clinician educators embrace this modality, rigorous research should focus on how and when they can best be used to create positive outcomes in learner practices. Further studies must investigate how podcasts can be optimized for knowledge retention while also having positive impacts on the hidden curriculum. Clinician educators must be involved in the conversation to build on what has been created thus far and how to best evaluate resources critically going forward. Moreover, curricula must evolve to teach learners how to critically evaluate digital media. Meanwhile, residents and attendings will have to adapt (and likely embrace) this new form of scholarship commonly cited on rounds.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Leonard Feldman, MD (Johns Hopkins), for his comments on an early version of this manuscript and Stuart Brigham, MD, for his work on The Curbsiders and assistance in guiding the internal survey of listener demographics.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors acknowledge their intellectual property COI: JB, MW, and PW as producers of The Curbsiders podcast; ST as producer of the CoreIM podcast; and RC as producer of the American College of Physician’s Annals on Call podcast.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Topf J. #31: Diuretics, leg cramps, and resistant hypertension with The Salt Whisperer [Internet]. The Curbsiders Internal Medicine Podcast. 2017. Available from: https://thecurbsiders.com/medical-education/s2e9-diuretics-leg-cramps-resistant-hypertension-salt-whisperer

- 2.Chen F, Lui AM, Martinelli SM. A systematic review of the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in medical education. Med Educ [Internet]. 2017 Jun [cited 2019 Apr 14];51(6):585–97. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28488303 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Cadogan M, Thoma B, Chan TM, Lin M. Free Open Access Meducation (FOAM): the rise of emergency medicine and critical care blogs and podcasts (2002-2013). Emerg Med J [Internet]. 2014 Oct [cited 2019 Feb 23];31(e1):e76–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24554447 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Colbert GB, Topf J, Jhaveri KD, Oates T, Rheault MN, Shah S, et al. The Social Media Revolution in Nephrology Education. Kidney Int Reports [Internet]. 2018 May [cited 2019 Aug 21];3(3):519–29. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29854960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Riddell J, Swaminathan A, Lee M, Mohamed A, Rogers R, Rezaie S. A Survey of Emergency Medicine Residents’ Use of Educational Podcasts. West J Emerg Med [Internet]. 2017 Feb 1 [cited 2019 Feb 23];18(2):229–34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28210357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Mallin M, Schlein S, Doctor S, Stroud S, Dawson M, Fix M. A survey of the current utilization of asynchronous education among emergency medicine residents in the United States. Acad Med [Internet]. 2014 Apr [cited 2019 Apr 14];89(4):598–601. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24556776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Malecki SL, Quinn KL, Zilbert N, Razak F, Ginsburg S, Verma AA, et al. Understanding the Use and Perceived Impact of a Medical Podcast: Qualitative Study. JMIR Med Educ [Internet]. 2019 Sep 19 [cited 2019 Sep 20];5(2):e12901. Available from:http://mededu.jmir.org/2019/2/e12901/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lin M, Thoma B, Trueger NS, Ankel F, Sherbino J, Chan T. Quality indicators for blogs and podcasts used in medical education: Modified Delphi consensus recommendations by an international cohort of health professions educators. Postgrad Med J [Internet]. 2015 Oct [cited 2019 Feb 23];91(1080):546–50. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26275428 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Colmers-Gray IN, Krishnan K, Chan TM, Seth Trueger N, Paddock M, Grock A, et al. The Revised METRIQ Score: A Quality Evaluation Tool for Online Educational Resources . AEM Educ Train. 2019 Jul 30; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Simpson D, Marcdante K, Souza KH, Anderson A, Holmboe E. Job Roles of the 2025 Medical Educator. J Grad Med Educ [Internet]. 2018 Jun [cited 2019 Aug 28];10(3):243–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29946376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Lehmann LS, Sulmasy LS, Desai S, ACP Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee. Hidden Curricula, Ethics, and Professionalism: Optimizing Clinical Learning Environments in Becoming and Being a Physician: A Position Paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2018 Apr 3 [cited 2019 Sep 15];168(7):506. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29482210 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Cook DA, Artino AR. Motivation to learn: an overview of contemporary theories. Med Educ. 2016;50(10):997–1014. doi: 10.1111/medu.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]